Abstract

Deficiency in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is associated with impaired visual and neurological development, cognitive decline, macular degeneration, and other neurodegenerative diseases. DHA is concentrated in phospholipids of the brain and retina, with photoreceptor cells having the highest DHA content of all cell membranes. The discovery that neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1; 10R, 17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,7Z,11E,13E,15Z,19Z-hexaenoic acid) is a bioactive mediator of DHA sheds light on the biological importance of this fatty acid. In oxidative stress-challenged human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, human brain cells, or brain ischemia-reperfusion, NPD1 synthesis is enhanced as a response for sustaining homeostasis. Thus, neurotrophins, Abeta peptide (Aβ)42, calcium ionophore A23187, interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), or DHA supply enhances NPD1 synthesis. NPD1, in turn, upregulates the antiapoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family and decreases the expression of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. In human neural cells, DHA attenuates Aβ42 secretion, resulting in concomitant formation of NPD1. NPD1 repressed Aβ42-triggered activation of proinflammatory genes and upregulated the antiapoptotic genes encoding Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and Bfl-1(A1) in human brain cells in culture. Overall, NPD1 signaling regulates brain and retinal cell survival via the induction of antiapoptotic and neuroprotective gene-expression programs that suppress Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity and other forms of cell injury. These in turn support homeostasis during brain and retinal aging, counteract inflammatory signaling, and downregulate events that support the initiation and progression of neurodegenerative disease.

Introduction

There is growing awareness and interest in the biological importance of (n-3) fatty acids, particularly as they relate to brain development, vision, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases. The (n-3) fatty acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA),4 has its highest concentrations in the human body as an acyl group of phospholipids in the central nervous system, especially in photoreceptor discs and in synaptic membranes. DHA is necessary for retina and brain development (1,2), memory formation, synaptic function, and neuroprotection. This fatty acid has been implicated in several functions, such as those in photoreceptor biogenesis and function (3–5), memory (6), excitable membranes functions (7), and neuroprotection (8). One property that the brain and retina share, with respect to (n-3) fatty acids, is their ability to retain DHA, even during extended dietary deprivation of (n-3) essential fatty acids. To efficiently reduce DHA content in brains and retinas of rodents and nonhuman primates, dietary deprivation for over 1 generation has been required, and the result was impaired retinal and brain function (9,10).

Epidemiological studies support the theory that (n-3) fatty acids slow down cognitive decline in the elderly (11). On the other hand, at least 11 observational studies and 4 clinical trials did not conclusively demonstrate that DHA plays a favorable role in the prevention or treatment of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) (11). In AD transgenic mice, dietary DHA supplementation restored cerebral blood volume, reduced (Abeta peptide) Aβ deposition, ameliorated Aβ pathology (12–14), and downregulated Aβ release from aged human neural cells (15). DHA also exerts antiinflammatory and antiapoptotic actions (8,16,17).

Mechanisms underlying the protective actions of DHA are not well understood. DHA is prone to free-radical mediated peroxidation and enzyme-catalyzed oxygenation. Peroxidation products of DHA accumulate during brain ischemia-reperfusion and in neurodegeneration; these products in turn form protein adducts and other cytotoxic molecules that participate in free radical-mediated injury in AD (18,19). The identification of the DHA-derived docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1:10R,17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,7Z,11E,15E,19Z hexaenoic acid) provides new insight into the protective bioactivity of DHA (20–22). NPD1 elicits neuroprotective activity in brain ischemia-reperfusion (Fig. 1) in oxidative-stressed retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, and it promotes neuronal and glial cell survival (21,22). DNA microarray profiling suggests a downregulation of proinflammatory genes as well as of some proapoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 family in cellular AD models (15). NPD1 further influences beta-amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) processing and the release of Aβ peptides, and its precursor DHA elicits an Aβ-lowering effect both in vitro and in vivo (23–25).

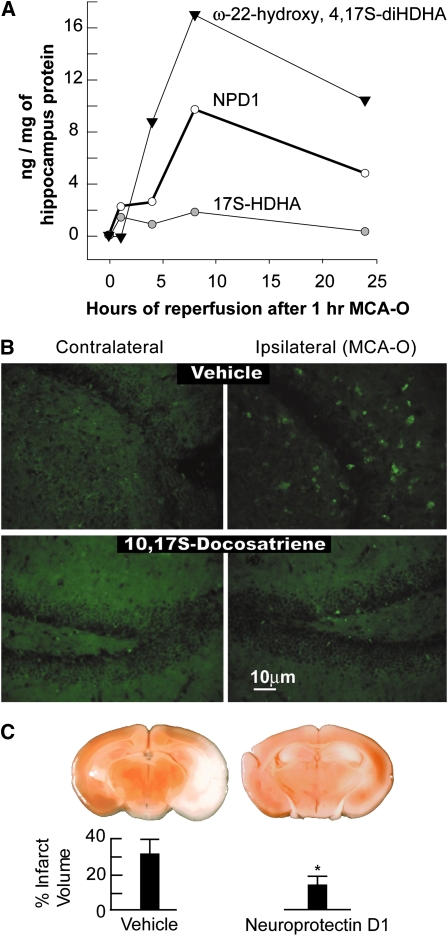

FIGURE 1 .

NPD1 is endogenously produced and decreases polymorphonuclear infiltration after ischemia-reperfusion in brain. (A) Time course of accumulation of 17S-HDHA, NPD1 (10R, 17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,7Z,11E,13E,15Z,19Z-hexaenoic acid), and ω-22-hydroxy-4,17S-diHDHA in the ipsilateral hippocampus of mice during reperfusion after 1 h of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). There was an enhanced accumulation of ω-22-hydroxy-4,17S-diHDHA, a product of an oxidative pathway, and 10,17S-docosatriene. (B) Immunocytochemical visualization of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (green fluorescence) that exhibit myeloperoxidase immunoreactivity. Ipsilateral brain areas (ischemic area) show positive green fluorescence (vehicle) as compared with contralateral tissue. The areas shown correspond to the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. NPD1-infused mice (400 ng over 48 h) exhibited a large reduction in green fluorescence. (C) Sectioning and TTC staining after NPD1 infusion through an Alzet mini-pump implanted into the third ventricle. The graph depicts the percentage of the total brain coronal area that was TTC stained. Bars are mean ± SD, n = 6. Asterisk indicates P < 0.002 (Student's t test). Adapted with permission from (21).

NPD1 is reduced in the AD cornu ammonis 1 hippocampal region and the neocortex, but not in other unaffected areas of the brain. The expression of key enzymes for NPD1 biosynthesis, cytosolic phospholipase A(2) [cPLA(2)], and 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) are altered in the AD hippocampal cornu ammonis 1 region (15).

Neuroprotectin D1 inhibits ischemia-reperfusion–mediated leukocyte infiltration and stroke size

Complexing DHA to human albumin after middle cerebral artery occlusion results in high-grade neurobehavioral and histological neuroprotection using a low albumin dose (0.63 g/kg), which in the absence of DHA is not robustly neuroprotective. The DHA–albumin complex also increases the production of NPD1 in the ipsilateral brain tissue (26,27).

NPD1 downregulates interleukin-1β–activated amyloid β peptide secretion during in vitro aging of neural progenitor cells

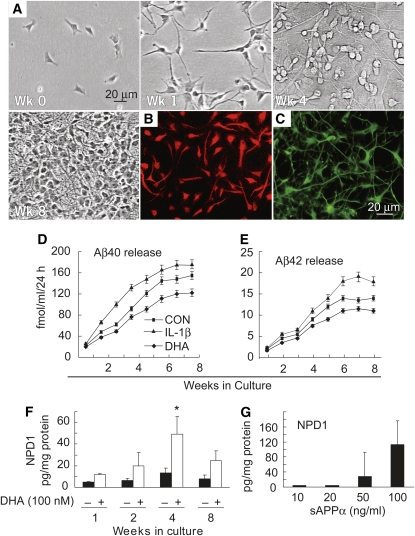

Human neuronal (HN) cells, a primary coculture of human neurons and glia, are a useful in vitro test system to explore stress signaling in the human brain, aging, and AD (28) (Fig. 2A). As indicated by βIII tubulin and glial fibrillary acidic protein immunostaining, these cultures are mixtures of equal proportions of neurons and glia under defined growth conditions at 4 wk of development (Fig. 2B, C). Interestingly, amyloidogenic Aβ peptides were progressively secreted from HN cells throughout 8 wk of culture (Fig. 2D, E). The ratio of Aβ40, a resident peptide of AD blood vessels, to Aβ42, which aggregates at lower concentrations than Aβ40 and is enriched within the amyloid plaque of AD (29), was ∼10:1 throughout this 8-wk period. To determine the effect of cytokine-mediated stress on aging HN cells, Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptide release was assayed in the incubation medium after addition of interleukin (IL)-1β, an inducer of reactive oxygen species and of oxidative stress (28,30). A time-dependent release of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides as a function of the number of weeks in culture was observed. Whereas soluble Aβ peptide secretion from HN cells was enhanced in the presence of interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), parallel experiments with DHA in the culture medium resulted in attenuation of Aβ peptide release (Fig. 2D, E).

FIGURE 2 .

DHA attenuates Aβ peptide secretion and serves as the precursor for NPD1 biosynthesis. sAPPα activates NPD1 formation. (A) HN cells were grown for up to 8 wk. (B and C) After 4 wk of culture, aging HN cells displayed approximately equal populations of neurons and glia and stained positive with the (red fluorescent) neuron-specific marker βIII tubulin (B) and the (green fluorescent) glia-specific marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (C). (D and E) HN cells in culture normally release Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides over 8 wk of aging. Secretion by HN cells of Aβ42 peptide was approximately one-tenth that of Aβ40 peptide; IL-1β (10 μg/L in modified HN cell maintenance medium) increased, and DHA decreased, the release of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides into the cell culture medium. CON, control. (F) DHA (100 nmol/L) induced NPD1 biosynthesis in HN cells, and this induction was age-dependent. (G) HN cells incubated in the presence of 10, 20, 50, and 100 μg/L of sAPPα showed dose-dependent upregulation of NPD1 formation. In D-G, values are means ± SE, n = 6. In F, *different from corresponding −, P < 0.05. Adapted with permission from (15).

Thus, HN cells use DHA as a precursor for NPD1 biosynthesis (Fig. 2F), yielding a 5-fold increase in NPD1 pool size at 4 wk of culture; at 8 wk, the concentration of this lipid mediator was about half that observed at 4 wk (Fig. 2F). These observations suggest that in aging HN cells, attenuation of the neurotoxic Aβ peptide release by DHA could be mediated, at least in part, by NPD1.

sAPPα is an agonist for NPD1 synthesis

Because DHA mediates the downregulation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 release and stimulates NPD1 production in HN cells, the possibility that NPD1 biosynthesis might be affected by the neurotrophic peptide soluble amyloid precursor protein alpha (sAPPα), a 612–amino acid fragment derived from α-secretase–mediated cleavage of βAPP, which appears to be neurotrophic (29), was investigated. sAPPα induces neuritogenesis and long-term survival of hippocampal and cortical neurons in culture and protects brain cells against the toxicity of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides and excitotoxic and ischemic injury, both in cell cultures and in vivo (31). It is important to note that the sAPPα generated via the α-secretase pathway does not give rise to the shorter amyloidogenic Aβ peptides; hence, the shunting of βAPP into the α-secretase pathway may have a beneficial action as a result of the relative lowering of Aβ peptide levels (29,31–33). A dose-dependent NPD1 induction by sAPPα (Fig. 2G) takes place under these conditions. For the additivity experiments with DHA and sAPPα, concentrations of sAPPα that elicited a small (20 μg/L) and a larger (100 μg/L) NPD1 induction were explored. sAPPα at 20 and 100 μg/L, in the presence of 50 nmol/L of added DHA, induced NPD1 abundance 2.3- and 5-fold, respectively, over that of controls treated with DHA alone. sAPPα at 20 μg/L in the absence of added DHA elicited negligible NPD1 synthesis; however, at 100 μg/L, sAPPα stimulation strongly triggered NPD1 synthesis in the absence of added DHA. These results indicate that some of the neurotrophic activity of sAPPα may be elicited, at least in part, by an upregulation in the biosynthesis of DHA-derived NPD1. This may be a complementary cell survival mechanism activated early in AD pathogenesis. sAPPα may activate the NPD1 biosynthetic enzymes cPLA(2) and/or a 15-LOX-like enzyme integral to NPD1 biosynthesis from DHA (13). Muscarine, a positive regulator of cPLA(2), is also a potent inducer of sAPPα in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (34); therefore, the enzymatic pathways involving PLA(2)-mediated DHA and NPD1 biosynthesis may exhibit positive feedback regulation through sAPPα. sAPPα also appears to protect neural cells against the proapoptotic action of thapsigargin, an inhibitor of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, and the adverse effect of thapsigargin can be abolished in cells overexpressing antiapoptotic Bcl-2. This implies premitochondrial signaling for pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein expression.

NPD1 counteracts Aβ peptide-induced apoptosis in neurons and glia

Because Aβ42 peptides induce apoptosis and cell death in both neurons and glia (35), the ability of NPD1 to protect HN cells against Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity was explored. For this purpose, 3-wk-old HN cells were incubated for an additional 3.5 d in serum-free HN cell maintenance medium containing 8 μmol/L in Aβ42 peptide. Except for the experiments depicted in Figure 2D–F, HN cells used in these studies were used at a developmental stage of 3–4 wk in culture, at which time there were approximately equal populations of neuronal and glial HN cells (Fig. 2A–C). Because selective cell loss may take place in older HN cell cultures (when neuronal cells drop out), the use of HN cells at a fixed age (and 50:50 neuronal/glial populations) was selected to minimize this possibility. Apoptosis occured in both neurons and glia. When NPD1 (50 nmol/L) was added to this test system, NPD1 protected both neurons and glia from Aβ42-directed apoptosis, as evidenced by quantification of Hoechst 33258 staining of compacted nuclei in control, Aβ42-treated, and Aβ42+NPD1-treated cell fields. Unlike control HN cells, Aβ42-treated HN cells also exhibited retracted neurites; however, when treated with NPD1, cells assumed extended neurites and an overall morphology resembling that of control cells.

15-LOX-1-catalyzed NPD1 synthesis mediates rescue from oxidative stress

During ischemia-reperfusion, aspirin enhances formation in the brain of 17R-resolvins, which are counterregulators of inflammation outside the brain. It could be argued that these DHA mediators enhance NPD1 bioactivity, decrease polymorphonuclear cell recruitment to the brain, and limit brain damage. Given the wide use of aspirin, the implied switch from endogenous to aspirin-triggered NPD1, which modulates homeostasis, is of great interest to neuraceuticals and dietary studies (21).

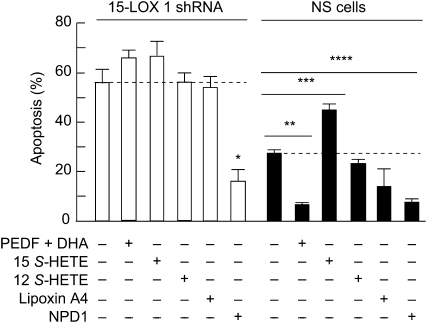

15-LOX-1-deficient RPE cells are more susceptible to perturbations that lead to apoptosis. The level of cell death is magnified in 15-LOX-1 deficient cells, as the concentration of oxidative stress mediators is increased. The magnitude of the response in the 15-LOX-1-deficient cells, in which the formation of NPD1 remained at low levels, was higher at 400, 600, and 800 μmol/L H2O2 [plus tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α]. These observations, along with the unchanged content of 15-LOX-1, suggest that the diminished 15-LOX-1 activity, which forms lesser amounts of NPD1, contributes to increased apoptosis in knockdown cells. The increased sensitivity of RPE cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis may be due to a decreased availability either of NPD1 or of other 15-LOX-1 products. DHA and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) protect RPE cells synergistically from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. NPD1 synthesis is enhanced under these conditions (22,36). To corroborate that NPD1 was in fact the 15-LOX-1 product responsible for protecting RPE knockdown cells, apoptosis induced in silenced cells using 600 μmol/L H2O2 and 10 μg/L TNFα was used to test protective bioactivity of PEDF and DHA, 15(S)- hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 12(S)-HETE, lipoxinA4, or NPD1. Only NPD1 rescued 15-LOX-1-deficient cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3). PEDF and DHA treatment was protective in nonsilenced cells but did not prevent apoptosis in the knockdown cells. Added DHA conversion to NPD1 is stimulated by PEDF; however, this conversion cannot take place in silenced cells. None of the arachidonic acid oxygenation products prevented cell death induced by oxidative stress (37).

FIGURE 3 .

NPD1 rescues stably transfected 15-lipoxygenase-1–deficient ARPE-19 cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. 15-Lipoxygenase-1 silenced cells were serum starved and treated with either PEDF-DHA, 15(S)-HETE, 12(S)-HETE, lipoxin A4, or NPD1 and 600 μmol/L H2O2 plus 10 μg/L TNFα for 16 h. 50 nmol/L of each lipid was added. The bars represent the means ± SE, n = 6 of the ratio between the cells that were stained positive with Hoechst and the total cell count. Asterisks indicate P-values: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005. Reproduced with permission from (37).

Concluding remarks

The interplay of DHA-derived neuroprotective signaling aims to counteract proinflammatory, cell-damaging events triggered by multiple, converging cytokine and amyloid peptide factors in AD. Amyloid peptide–mediated oxidative stress, the activation of microglia associated with Aβ peptide deposition, and excessive production of microglial-derived cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα, support progressive inflammatory episodes in AD (35,38–40). These noxious stimuli further orchestrate pathogenic gene-expression programs in stressed brain cells, thereby linking a cascade of caspase-mediated cell death pathways with apoptosis and neuronal demise (28,41). Neural mechanisms leading toward NPD1 generation from DHA thereby appear to redirect cellular fate toward successful brain cell aging (Fig. 4). The Bcl-2 pro- and antiapoptotic gene families, sAPPα, and NPD1 lie along a cell fate-regulatory pathway whose component members are highly interactive and have potential to function cooperatively in brain cell survival during aging and during the onset of neurodegeneration. Overall, they operate in large part through modulation of Aβ42-directed pathogenic events. Taken together, these data suggest that NPD1 induces an antiapoptotic, neuroprotective gene-expression program that regulates the secretion of Aβ peptides, resulting in the modulation of inflammatory signaling, neuronal survival, and the preservation of brain cell function. Agonists of NPD1 biosynthesis or NPD1 analogs may be useful for exploring therapeutic strategies for AD and related neurodegenerative disease.

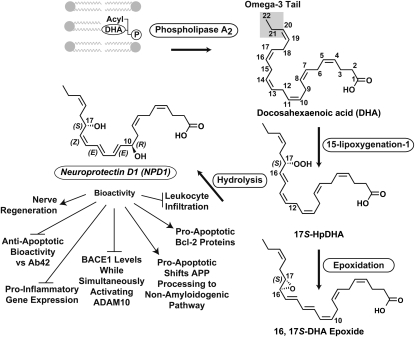

FIGURE 4 .

Biosynthesis of NPD1. A membrane phospholipid containing a docosahexaenoyl chain in sn-2 is hydrolyzed by phospholipase A2, generating free (unesterified) DHA. The carbons of DHA are numbered and the (n-3) fatty acid tail is highlighted. Lipoxygenation is then followed by epoxidation and hydrolysis, to generate NPD1. Bioactivity is depicted with arrows (activation) and bars (inhibition). Induction of nerve regeneration refers to cornea nerve regeneration (42–44). Adapted with permission from (44).

Acknowledgments

C.Z. and N.G.B designed the research, wrote the paper, and are responsible for the final content.

Published as a supplement to The Journal of Nutrition. Presented as part of the symposium entitled “DHA and Neurodegenerative Disease: Models of Investigation” given at the Experimental Biology 2009 meeting, April 19, 2009, in New Orleans, LA. This symposium was sponsored the American Society for Nutrition and supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Martek Bioscience. The symposium was chaired by Jay Whelan and Robert K. McNamara. Guest Editor for this symposium publication was Cathy Levenson. Guest Editor disclosure: no conflicts to disclose.

Supported by NIH, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R01 NS046741; NIH, National Eye Institute grant R01 EY005121; and NIH, National Center for Research Resources grant P20 RR016816.

Author disclosures: C. Zhang and N.G. Bazan, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: 15-LOX, 15-lipoxygenase; Aβ, Abeta peptide; AD, Alzheimer's disease; βAPP, beta-amyloid precursor protein; cPLA(2), cytosolic phospholipase A(2); DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HN, human neuronal; IL-1β, interleukin-1beta; NPD1, neuroprotectin D1; PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; RPE, retinal pigment epithelial; sAPPα, soluble amyloid precursor protein alpha; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

References

- 1.Diau GY, Hsieh AT, Sarkadi-Nagy EA, Wijendran V, Nathanielsz PW, Brenna JT. The influence of long chain polyunsaturate supplementation on docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid in baboon neonate central nervous system. BMC Med. 2005;3:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greiner RC, Winter J, Nathanielsz PW, Brenna JT. Brain docosahexaenoate accretion in fetal baboons: bioequivalence of dietary alpha-linolenic and docosahexaenoic acids. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RE, Maude MB, McClellan M, Matthes MT, Yasumura D, LaVail MM. Low docosahexaenoic acid levels in rod outer segments of rats with P23H and S334ter rhodopsin mutations. Mol Vis. 2002;8:351–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bicknell IR, Darrow R, Barsalou L, Fliesler SJ, Organisciak DT. Alterations in retinal rod outer segment fatty acids and light-damage susceptibility in P23H rats. Mol Vis. 2002;8:333–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organisciak DT, Darrow RM, Jiang YL, Blanks JC. Retinal light damage in rats with altered levels of rod outer segment docosahexaenoate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2243–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moriguchi T, Salem N, Jr. Recovery of brain docosahexaenoate leads to recovery of spatial task performance. J Neurochem. 2003;87:297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litman BJ, Niu SL, Polozova A, Mitchell DC. The role of docosahexaenoic acid containing phospholipids in modulating G protein-coupled signaling pathways: visual transduction. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16:237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HY, Akbar M, Lau A, Edsall L. Inhibition of neuronal apoptosis by docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3). J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheeler TG, Benolken RM, Anderson RE. Visual membranes: specificity of fatty acid precursors for the electrical response to illumination. Science. 1975;188:1312–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuringer M, Connor WE, Van Petten C, Barstad L. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid deficiency and visual loss in infant rhesus monkeys. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fotuhi M, Mohassel P, Yaffe K. Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease: a complex association. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5:140–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calon F, Lim GP, Yang F, Morihara T, Teter B, Ubeda O, Rostaing P, Triller A, Salem N, Jr., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Neuron. 2004;43:633–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green KN, Martinez-Coria H, Khashwji H, Hall EB, Yurko-Mauro KA, Ellis L, LaFerla FM. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid and docosapentaenoic acid ameliorate amyloid-beta and tau pathology via a mechanism involving presenilin 1 levels. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4385–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooijmans CR, Van der Zee CE, Dederen PJ, Brouwer KM, Reijmer YD, van Groen T, Broersen LM, Lütjohann D, Heerschap A, Kiliaan AJ. Changes in cerebral blood volume and amyloid pathology in aged Alzheimer APP/PS1 mice on a docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) diet or cholesterol enriched Typical Western Diet (TWD). Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Marcheselli VL, Bodker M, Botkjaer A, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. A role for docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Périz A, Planagumà A, Gronert K, Miquel R, López-Parra M, Titos E, Horrillo R, Ferré N, Deulofeu R. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) blunts liver injury by conversion to protective lipid mediators: protectin D1 and 17S-hydroxy-DHA. FASEB J. 2006;20:2537–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Ruan XZ, Powis SH, Fernando R, Mon WY, Wheeler DC, Moorhead JF, Varghese Z. EPA and DHA reduce LPS-induced inflammation responses in HK-2 cells: evidence for a PPAR-gamma-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 2005;67:867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts LJ, Fessel JP, Davies SS, Roberts, 2nd LJ, Fessel JP, Davies SS. The biochemistry of the isoprostane, neuroprostane, and isofuran pathways of lipid peroxidation. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Gray SL, Wilson A, Kohama SG, Crane PK, Breitner JC, Montine TJ. Free radical damage to cerebral cortex in Alzheimer's disease, microvascular brain injury, and smoking. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:226–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong S, Gronert K, Devchand PR, Moussignac RL, Serhan CN. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14677–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcheselli VL, Hong S, Lukiw WJ, Tian XH, Gronert K, Musto A, Hardy M, Gimenez JM, Chiang N, et al. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43807–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8491–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim GP, Calon F, Morihara T, Yang F, Teter B, Ubeda O, Salem N, Jr., Frautschy SA, Cole GM. A diet enriched with the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid reduces amyloid burden in an aged Alzheimer mouse model. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3032–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oksman M, Iivonen H, Hogyes E, Amtul Z, Penke B, Leenders I, Broersen L, Lütjohann D, Hartmann T, Tanila H. Impact of different saturated fatty acid, polyunsaturated fatty acid and cholesterol containing diets on beta-amyloid accumulation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahlin C, Pettersson FE, Nilsson LN, Lannfelt L, Johansson AS. Docosahexaenoic acid stimulates non-amyloidogenic APP processing resulting in reduced Abeta levels in cellular models of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belayev L, Marcheselli VL, Khoutorova L, Rodriguez de Turco EB, Busto R, Ginsberg MD, Bazan NG. Docosahexaenoic acid complexed to albumin elicits high-grade ischemic neuroprotection. Stroke. 2005;36:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belayev L, Khoutorova L, Atkins KD, Bazan NG. Robust docosahexaenoic acid-mediated neuroprotection in a rat model of transient, focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:3121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 and presenilin-1 gene expression induced by interleukin-1beta and amyloid beta 42 peptide is potentiated by hypoxia in primary human neural cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selkoe D, Kopan R. Notch and Presenilin: regulated intramembrane proteolysis links development and degeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:565–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur J, Dhaunsi GS, Turner RB. Interleukin-1 and nitric oxide increase NADPH oxidase activity in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:26–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein TD, Johnson JA. Genetic programming by the proteolytic fragments of the amyloid precursor protein: somewhere between confusion and clarity. Rev Neurosci. 2003;14:317–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahr BA, Hoffman KB, Yang AJ, Hess US, Glabe CG, Lynch G. Amyloid beta protein is internalized selectively by hippocampal field CA1 and causes neurons to accumulate amyloidogenic carboxyterminal fragments of the amyloid precursor protein. J Comp Neurol. 1998;397:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazan NG. Synaptic lipid signaling: significance of polyunsaturated fatty acids and plateletactivating factor. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:2221–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster NJ, Green KN, Peers C, Vaughan PF. Altered processing of amyloid precursor protein in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y by chronic hypoxia. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1262–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, McLaughlin R, Goodyer C, LeBlanc A. Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid beta peptide1–42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:519–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, Barreiro S, Hu J, Bok D, Bazan NG. Neurotrophins enhance retinal pigment epithelial cell survival through neuroprotectin D1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calandria JM, Marcheselli VL, Mukherjee PK, Uddin J, Winkler JW, Petasis NA, Bazan NG. Selective survival rescue in 15-lipoxygenase-1-deficient retinal pigment epithelial cells by the novel docosahexaenoic acid-derived mediator, neuroprotectin D1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17877–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:741–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HJ, Chae SC, Lee DK, Chromy B, Lee SC, Park YC, Klein WL, Krafft GA, Hong ST. Selective neuronal degeneration induced by soluble oligomeric amyloid beta protein. FASEB J. 2003;17:118–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong HS, Hwang EM, Sim HJ, Cho HJ, Boo JH, Oh SS, Kim SU, Mook-Jung I. Interferon gamma stimulates beta-secretase expression and sAPPbeta production in astrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:922–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colangelo V, Schurr J, Ball MJ, Pelaez RP, Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ. Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:462–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esquenazi S, He J, Li N, Bazan NG, Esquenazi I, Bazan HE. Comparative in vivo high-resolution confocal microscopy of corneal epithelium, sub-basal nerves and stromal cells in mice with and without dry eye after photorefractive keratectomy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35:545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cortina MS, He J, Li N, Bazan NG, Bazan H. PEDF plus DHA Induces Neuroprotectin D1 Synthesis and Corneal Nerve Regeneration after Experimental Surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Bazan NG. Homeostatic regulation of photoreceptor cell integrity: significance of the potent mediator neuroprotectin D1 biosynthesized from docosahexaenoic acid: the Proctor Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4866–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]