Abstract

We evaluated the influence of age and sex on the relationship between central and peripheral vasodilatory capacity. Healthy men (19 younger, 12 older) and women (17 younger, 17 older) performed treadmill and knee extensor exercise to fatigue on separate days while maximal cardiac output (Q, acetylene uptake) and peak femoral blood flow (FBF, Doppler ultrasound) were measured, respectively. Maximal Q was reduced with age similarly in men (Y: 23.6 ± 2.7 vs. O: 17.4 ± 3.5 l/min; P < 0.05) and women (Y: 17.7 ± 1.9 vs. O: 12.3 ± 1.6 l/min; P < 0.05). Peak FBF was similar between younger (Y) and older (O) men (Y: 2.1 ± 0.5 vs. O: 2.2 ± 0.7 l/min) but was lower in older women compared with younger women (Y: 1.9 ± 0.4 vs. O: 1.4 ± 0.4 l/min; P < 0.05). Maximal Q was positively correlated with peak FBF in men (Y: r = 0.55, O: r = 0.74; P < 0.05) but not in women (Y: r = 0.34, O: r = 0.10). Normalization of cardiac output to appendicular muscle mass and peak FBF to quadriceps mass reduced the correlation between these variables in younger men (r = 0.30), but the significant association remained in older men (r = 0.68; P < 0.05), with no change in women. These data suggest that 1) aerobic capacity is associated with peripheral vascular reserve in men but not women, and 2) aging is accompanied by a more pronounced sex difference in this relationship.

Keywords: aging, aerobic capacity, blood flow, vasodilation, gender

it has been more than three decades since Clausen's original report (3) highlighting a significant inverse relationship between systemic maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) and the decrease in peripheral vascular resistance during maximal exercise in humans. This relationship has been interpreted to reflect a matching between maximal aerobic capacity and peripheral vasodilatory capacity. Since this original observation, studies have demonstrated that V̇o2max is also correlated with other indexes of peripheral vascular reserve; most often examined is the peak vascular conductance response of the calf musculature, which exhibits a positive linear association with V̇o2max (32). The relationship between V̇o2max and peak calf conductance is particularly robust when examined in aerobically trained populations (22, 32) or when plotted across a broad range of aerobic fitness levels (15, 17, 23, 31). However, close inspection of plots that combine individuals of different age and/or sex reveals considerable between-group variation, with some subgroups exhibiting a significantly blunted or absent relationship (23).

One explanation for the apparent between-group variation is that the relationship between V̇o2max and peripheral vascular reserve can be altered in conditions that induce a mismatch between central and peripheral vascular adaptations (11). For example, with advancing age women and men experience similar relative declines in maximal cardiac output and V̇o2max (2, 4, 7, 13, 25). However, men may exhibit a preserved peripheral vascular reserve with age as suggested by modest (18) to no decrement (28) in peak leg blood flow during isolated muscle mass exercise in older men compared with younger men. Conversely, in women, peripheral vascular reserve may be reduced with age as demonstrated by lower peak leg blood flow and vascular conductance in older women relative to younger individuals (28). These sex-specific vascular adaptations with aging may alter both the relationship between maximal aerobic capacity and peripheral vasodilation as well as the cardiovascular determinants of peak exercise capacity.

Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that the relationship between central and peripheral vascular reserve is altered with aging in a sex-specific manner. Maximal flow-generating capacities of the heart (cardiac output) and leg muscles (peak leg blood flow) were assessed via graded treadmill and single-leg knee extensor exercise, respectively, because these modalities yield the highest achievable estimates of systemic and active skeletal muscle blood flow and perfusion in humans (1).

METHODS

Participants.

Sixty-five participants between 20–35 yr of age (19 younger men, 17 younger women) and 60–79 yr of age (12 older men, 17 older women) completed this study. All participants were normotensive (≤140/90 mmHg), apparently healthy, nonsmokers and abstained from caffeine, aspirin/ibuprofen, and herbal supplements for at least 12 h before exercise testing. Younger women were studied in days 1–7 of their menstrual cycle only during the study visit involving knee extensor exercise to standardize the influence of sex hormones on vasodilator function. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate. This study was approved by the Office for Research Protections and the Institutional Review Board at The Pennsylvania State University and is in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Body composition and muscle mass.

Total and regional body composition were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Hologic QDR 4500W) as described previously (29). Quadriceps muscle mass was estimated from thigh volume as previously described (16, 28).

Treadmill exercise testing.

Participants performed graded treadmill exercise tests to peak effort using a modified Balke protocol. The protocol consisted of a 2-min warm-up at 2.5 mph followed by adjustment of the speed to elicit ∼75% of age-predicted peak heart rate after which the intensity of exercise (2% increase in elevation) increased every 2 min until the participants reached volitional fatigue. Blood pressures were measured via brachial auscultation during the second minute of each exercise stage until participants indicated an effort level of 15 (“Hard”) or above on the Borg 6–20 rating of perceived exertion. Blood pressure measurements were not attempted during peak effort to enable participants to fully engage both arms and give maximum effort without disturbance. However, in a subgroup of participants (younger men, n = 9; older men, n = 7; younger women, n = 8; older women, n = 9) the last blood pressure measured was at a time that corresponded to ∼90% peak oxygen uptake (V̇o2peak) and therefore was used as peak blood pressure for data analyses. Pulmonary oxygen uptake (V̇o2) was measured using analysis of expired gases by a Parvomedics metabolic cart (Sandy, UT).

Cardiac output measurement.

The open-circuit acetylene uptake method was used for determination of cardiac output. This technique has been validated against the direct Fick technique (14) and has proven reliable for measurement of cardiac output during exercise in both older and younger adults (2).

Graded knee extensor exercise.

Single-leg knee extensor exercise was performed as described previously (28). Exercise stages were 3 min in duration, and work rate increased by 8 W in men and 4.8 W in women to produce similar time to exhaustion in all groups (28). A Doppler ultrasound machine (HDI 5000, Philips, Bothell, WA) was used to measure mean blood velocity and vessel diameter of the left common femoral artery. During knee extensor exercise, signals were recorded at a sampling frequency of 400 Hz and stored using a Powerlab system (AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Diameter measurements were analyzed using edge-detection software (Brachial Analyzer Software, Medical Imaging Applications; Iowa City, IA). Femoral blood flow and vascular conductance were calculated as previously described (27, 28). Heart rate and beat-to-beat blood pressure (radial tonometry of the right hand; Colin, Medical Instruments) were measured continuously.

Data analysis and computations.

For all study variables, values were calculated as the average over the last minute of each stage. Peak knee extensor measurements were calculated with first- or second-minute data if the subject did not complete the entire final workload. Peak femoral blood flow measurements were calculated with the diameter from the previous work rate. In a subgroup of participants where peak (∼90% of V̇o2peak) blood pressures were obtained, systemic vascular resistance was calculated by dividing peak blood pressure by the corresponding maximal cardiac output.

Statistical analysis.

Minitab version 14 and SAS version 9.1 software were used to perform all statistical analyses. A general linear model ANOVA procedure was used to test for significant effects of age, sex, and the age × sex interaction for outcome variables. Pearson correlations were calculated to determine associations between outcome variables. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05 for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Physical characteristics.

Anthropometric characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Effects for an age-sex interaction were insignificant, suggesting that the age group differences in overall body size and composition were similar between men and women.

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics for healthy younger and older men and women

| Younger Men (20–32 yr old) | Older Men (61–79 yr old) | Younger Women (20–30 yr old) | Older Women (61–73 yr old) | Age × Sex Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 19 | 12 | 17 | 17 | |

| Age, yr | 25 ± 4 | 68 ± 3* | 24 ± 3 | 67 ± 4* | |

| Height, cm | 179.6 ± 6.2 | 175.7 ± 8.2 | 164.3 ± 6.6 | 160.7 ± 6.1 | P = 0.5 |

| Weight, kg | 80.1 ± 7.3 | 78.4 ± 11.3 | 60.9 ± 8.7 | 64 ± 8.2 | P = 0.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8 ± 2.2† | 25.4 ± 2.8 | 22.5 ± 2.5 | 24.8 ± 2.8 | P = 0.3 |

| Body fat, % | 19.9 ± 4.8† | 22.4 ± 3.6*† | 29.1 ± 6 | 35 ± 4.9 | P = 0.3 |

| Quadriceps mass, kg | 1.9 ± 0.2† | 1.7 ± 0.2*† | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3* | P = 0.9 |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of subjects. BMI, body mass index.

Significant age difference within same sex group (P < 0.05).

Significant sex difference within same age group (P < 0.05).

Peak exercise responses.

Table 2 displays group average data for peak exercise responses by mode of exercise. During treadmill exercise, V̇o2max was higher in younger vs. older individuals in both sexes (P < 0.05), even when normalized to body weight and appendicular muscle mass (i.e., index of active muscle mass). Younger men and women were of average fitness level while older participants were slightly less fit than their younger counterparts (P < 0.05). Despite this age difference, on average all groups achieved maximal heart rates > 97% predicted and a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) > 1.09, indicating maximal effort by all participants during treadmill exercise.

Table 2.

Exercise capacity data for healthy younger and older men and women

| Younger Men (20–32 yr old) | Older Men (61–79 yr old) | Younger Women (20–30 yr old) | Older Women (61–73 yr old) | Age × Sex Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 19 | 12 | 17 | 17 | |

| Treadmill exercise | |||||

| V̇o2max, l/min | 3.4 ± 0.5† | 2.2 ± 0.4*† | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2* | P = 0.01 |

| V̇o2max, ml•kg−1•min−1 | 45.8 ± 4.1† | 30.2 ± 4.1*† | 38.1 ± 5.4 | 23.5 ± 2.9* | P = 0.7 |

| V̇o2max, ml•ApMM−1•min−1 | 126.1 ± 11.3 | 91.8 ± 9.9* | 133.5 ± 14.8 | 91.1 ± 7.9* | P = 0.2 |

| V̇o2max, percentile | 56.5 ± 17.9 | 31.3 ± 15.4* | 58.4 ± 19.1 | 33.2 ± 16.1* | P = 0.9 |

| Maximal heart rate, beats/min | 190.2 ± 9.2 | 152.8 ± 12.0* | 191.8 ± 9.8 | 154.5 ± 0.9* | P = 0.9 |

| Maximal heart rate, %predicted | 101.4 ± 4.3 | 97.3 ± 7.5 | 101 ± 5.4 | 97.4 ± 4.5 | P = 0.8 |

| Maximal cardiac output, l/min | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 17.4 ± 3.5* | 17.7 ± 1.9 | 12.3 ± 1.6* | P = 0.3 |

| Maximal stroke volume, ml/beat | 142.5 ± 18.2† | 134.3 ± 22.3† | 103.2 ± 15 | 97.8 ± 12.8 | P = 0.4 |

| RER | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 1.10 ± 0.05 | P = 0.9 |

| RPE | 19 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | P = 0.6 |

| Knee extensor exercise | |||||

| Peak power output, W | 40.4 ± 6.8† | 33.3 ± 8.8*† | 24.9 ± 4.2 | 21.2 ± 4.2* | P = 0.2 |

| Peak power output, W/kg QMM | 16.2 ± 3.3† | 15.3 ± 4.6 | 12.6 ± 2.1 | 12.8 ± 3.3 | P = 0.4 |

| Peak leg blood flow, l/min | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.7† | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4* | P = 0.03 |

| Peak leg perfusion, l•min−1•kg QMM−1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | P = 0.04 |

| Peak leg conductance, ml•min−1•mmHg−1 | 18.5 ± 3.6 | 21.0 ± 7.5† | 20.9 ± 6.2 | 13.6 ± 4.4* | P < 0.01 |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of subjects. V̇o2max, maximal oxygen uptake; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; ApMM, appendicular muscle mass; QMM, quadriceps muscle mass.

Significant age difference within same sex group (P < 0.05).

Significant sex difference within same age group (P < 0.05).

The effects of age on hemodynamic responses to maximal treadmill exercise are generally consistent with previously published data for non-aerobically trained men and women (23). Maximal cardiac output was higher in men than women (P < 0.05) and was significantly reduced by an average 25–30% with age in both sexes (P < 0.05). Group averages for femoral hemodynamic responses to knee extensor exercise are consistent with our previously published data in non-aerobically trained men and women (28). Peak femoral blood flow was similar between younger and older men (P = 0.54) but was 26% lower in older women compared with younger women (P = 0.001). Similar findings were found for peak vascular conductance (see Table 2).

Relationships between central and peripheral vascular reserve.

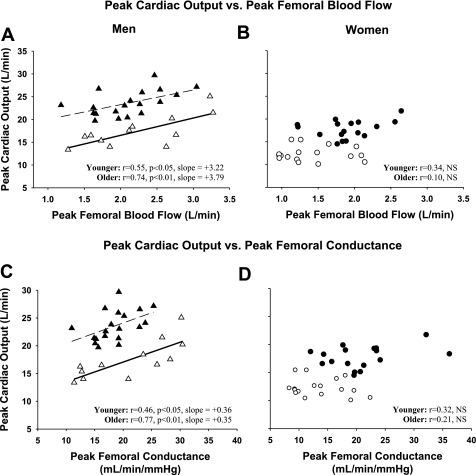

Relationships between maximal cardiac output and peak femoral blood flow are displayed in Fig. 1A for men and Fig. 1B for women. Maximal cardiac output was positively correlated with peak absolute femoral blood flows (in l/min) in men (younger: r = 0.55, P = 0.02; older: r = 0.74, P < 0.01) but not in women (younger: r = 0.34, P = 0.22; older: r = 0.10, P = 0.90). Similarly, V̇o2max was correlated to peak femoral blood flow in men (young: r = 0.56; older: r = 0.62; P < 0.05) but not in women (younger: r = 0.11; older: r = 0.11; P > 0.6). These relationships held true when femoral vascular conductance was used as an index of peripheral vascular reserve such that a significant positive correlation was found between maximal cardiac output and peak femoral vascular conductance in men (younger: r = 0.48; older: r = 0.77; P < 0.05) but not in women (younger: r = 0.32; older: r = 0.21; p>0.2) (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

Peak cardiac output during treadmill exercise vs. peak quadriceps blood flow during knee extensor exercise: ▴, younger men (n = 19); ▵, older men (n = 12) (A); ●, younger women (n = 17); ○, older women (n = 17) (B). Peak cardiac output during treadmill exercise vs. femoral artery conductance during peak knee extensor exercise: ▴, younger men; ▵, older men (C); ●, younger women; ○, older women (D).

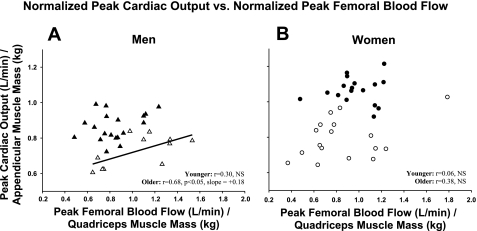

Normalization of maximal cardiac output to appendicular muscle mass and peak femoral blood flow to quadriceps muscle mass abolished the correlation between these variables in younger men (r = 0.30, P = 0.21) while the positive correlation remained in older men (r = 0.68, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). The lack of relationship between maximal cardiac output and peak femoral blood flow persisted in women (younger: r = 0.06, P = 0.8; older: r = 0.38, P = 0.13) after normalization of these variables to muscle mass (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Peak cardiac output during treadmill exercise normalized to appendicular muscle mass vs. femoral blood flow during peak knee extensor exercise normalized to quadriceps muscle mass: ▴, younger men (n = 19); ▵, older men (n = 12) (A); ●, younger women (n = 17); ○, older women (n = 17) (B).

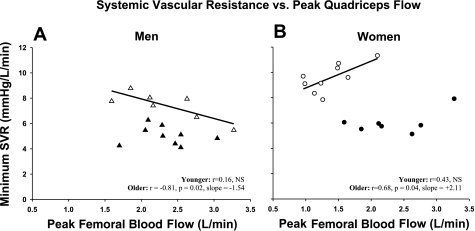

Last, in a subgroup of participants in whom treadmill blood pressures at peak exercise (∼90% V̇o2max) were available, we examined the relationship between systemic vascular resistance and peak femoral blood flow during knee extensor exercise (Fig. 3). No associations were found in the younger groups (men: r = 0.16, P = 0.67; women: r = 0.43, P = 0.34). In the older groups, associations were found that were significant and directionally opposite with the men having a negative correlation (r = −0.81, P = 0.02) and the women exhibiting a positive correlation (r = 0.68, P = 0.04). While indirect, and limited to a small subsample of the present participants, these results suggest a fundamentally different relationship between the local capacity for exercise-induced hyperemia and the systemic vasodilatory response to intense whole body treadmill exercise.

Fig. 3.

Subset analysis of the minimum vascular resistance attained during peak treadmill exercise (∼90% maximal oxygen uptake) vs. femoral blood flow during peak knee extensor exercise: ▴, younger men (n = 9); ▵, older men (n = 7) (A); ●, younger women (n = 8); ○, older women (n = 9) (B). SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

DISCUSSION

The postulated link between systemic aerobic capacity and peripheral vascular reserve has been largely based on studies in men, with limited attention to intersubject variation or between-group differences in this relationship (i.e., age or sex comparisons), particularly among healthy, non-aerobically trained populations. In the present study we measured maximal cardiac output, a chief determinant of aerobic capacity, and assessed the peak blood flow and conducting capacity of the contracting knee extensor muscles to gain further insight into this balance and possible sex-dependent alterations with normal aging. The principal new findings are 1) maximal cardiac output is significantly correlated with peak knee extensor exercise blood flow and conductance in average fit men but not in women, and 2) sex differences in the balance between central and peripheral vasodilatory capacity appear more pronounced in older adults. These findings suggest sex- and potentially age-dependent differences in systemic cardiovascular regulation during whole body exercise such that leg vascular reserve influences peak achievable oxygen delivery and uptake in men but not women.

Associations observed in men.

There generally exists a positive linear association between maximal aerobic capacity (V̇o2max in ml·kg−1·min−1) and peak calf vascular conductance in men (15, 23, 31, 32). Our finding of a significant positive correlation between maximal cardiac output and peak femoral blood flow (and conductance) in average fit men is consistent with these previous reports and extends our understanding of this relationship to a model that includes multiple vasomotor stimuli (e.g., endothelium-derived factors, metabolites, sympathetic activity) present during muscular contraction. Interestingly, the link between systemic oxygen transport and peripheral vascular reserve was markedly stronger in older men, and in fact persisted in this group but not in younger men when peak femoral blood flow was normalized to quadriceps mass. The stronger relationship found in older men may reflect an ability to utilize a greater fraction of their capacity for leg vasodilation during exercise relative to other groups.

The modest correlations between these variables in younger men are consistent with several reports in the literature showing lower or nonsignificant correlations between V̇o2max and peak calf conductance in normal-fit compared with endurance-trained younger men (11, 31, 32). We did not include endurance-trained participants in the present study so we cannot address how higher fitness levels might influence the relationship between maximal cardiac output and peak femoral blood flow. However, we speculate that the central (cardiac output and V̇o2max) and peripheral (vasodilatory capacity) adaptations accompanying endurance training would only strengthen the relationships found in the present study as demonstrated previously using peak calf vascular conductance (22, 32).

Lack of association observed in women.

In contrast to the results for men, the present study found no significant correlations between these variables in younger or older women regardless of how the vascular data were expressed (peak blood flow or conductance) or normalized (absolute or relative to quadriceps mass). The deviation from the relationship between aerobic capacity and peripheral vascular reserve also differed in women based on age. Specifically, younger women had a lower maximal cardiac output than would be predicted from their peak femoral blood flow and conductance relative to younger men. In contrast, older women had a lower peak femoral blood flow than would be predicted from their maximal cardiac output relative to older men. This interpretation suggests that in women peripheral adaptations with age is a factor contributing to the altered balance between systemic aerobic capacity and peripheral vasodilation.

Possible sex differences in the relationship between maximal aerobic capacity and calf vasodilatory capacity have not been explicitly discussed in the literature because, to our knowledge, only one study differentiated responses in women and men (23). Close inspection of that report suggests a weak relationship exists between these variables in women, particularly in those who are older. Collectively these studies [the present study and that of Martin et al. (23)] suggest that in women, systemic aerobic capacity bears a relatively weak association with measures of leg vasodilator reserve.

The mechanisms contributing to the sex-specific differences in the association between aerobic capacity and local vascular reserve are unknown. Relative aerobic fitness level and maximal effort during treadmill testing are unlikely explanations given the similarity in lean body mass-normalized V̇o2max between women and men of a similar age group and the consistent use of V̇o2max criteria across groups (Table 2). It is possible that the factor(s) underlying this apparent sex-specific dichotomy differ depending on age. This is suggested by the fact that normalizing peak femoral blood flow to estimates of active muscle (quadriceps mass) abolishes the sex-specific association between these variables in the younger groups but not in the older groups (Fig. 2).

Disparate associations between older men and women: potential implications.

Sex-based differences in the relationships between peak femoral blood flow and both maximal cardiac output and minimum systemic vascular resistance were most evident between older women and men, suggesting a more pronounced sex difference with increasing age. This is consistent with other studies describing disparate alterations in cardiovascular regulation at rest (9, 10, 24) and during orthostatic challenges (5, 6, 33) with advancing age and/or between men and women. We cannot determine the precise mechanism(s) underlying the exercise-specific alterations indentified in the present study. Although the ability to reduce systemic vascular resistance appeared to be impaired in older compared with younger groups (Fig. 3), it is important to note that both older men and older women did exhibit significant reductions in systemic vascular resistance during graded whole body exercise (across percent V̇o2max; data not shown). Thus, despite the disparate associations between peripheral vascular reserve and systemic hemodynamics in older women vs. men, the overall ability to reduce systemic vascular resistance during whole body exercise appears similarly affected by the normal aging process in both sexes. This may suggest disparate vascular control strategies are used by older men and women to regulate systemic blood pressure during exercise. For example, sex-specific alterations in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (24) and/or buffering of sympathetic outflow (26) with advancing age could influence the mechanisms by which older adults decrease vascular resistance during intense whole body exercise. It is also possible that the vascular reserve capacity of the leg muscles in older women (as reflected during knee extensor exercise) may have less impact on systemic blood pressure responses when large increases in cardiac output (intense treadmill exercise) are sufficient to offset the reduction in systemic vascular resistance.

Experimental considerations.

The correlative approach taken in the present study assumes that mode-specific differences including body posture, contraction patterns/rates, respiratory muscle activity, thermoregulation, and possibly baroreflex modulation of sympathetic muscle activity do not alter our interpretation of the balance between peripheral vasodilator function and maximal cardiac output. Aerobic fitness level differed between younger and older groups in the present study. We do not believe this influenced our primary findings since previous studies show the relationship between peripheral vascular reserve and V̇o2max to be strengthened with endurance training (22, 32). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that our findings in men would be exaggerated if we had examined older men at a higher fitness level that was similar to the younger men. We would expect no difference in our findings in higher fit older women since younger women did not exhibit a significant correlation.

Additionally, peak femoral blood flows measured in our participants are lower than values reported in previous studies (1, 18, 20, 21). Thermodilution estimates of peak femoral blood flow during knee extensor exercise typically exceed 5 l/min in men while the present study measured peak flows up to 3 l/min in young and older men. Although our femoral blood flow values with respect to external work rate are comparable to other studies using Doppler ultrasound (8, 12, 19, 27, 28), we believe several factors can explain the discrepancy in peak femoral blood flow between thermodilution-based studies and the present study. First, the contraction frequency used in the present study [40 kicks per minute (kpm)] is lower than other studies (60 kpm) that report higher peak blood flow (1, 18, 30). Second, participants in the present study performed exercise in a nearly supine position, which may influence exercise performance and driving pressure for blood flow. Last, our participants were low to moderately fit and the classic thermodilution-based studies generally included highly-trained individuals. Together, these differences likely explain the lower peak quadriceps power output in our men (30–40 W) compared with previous studies (>55 W), and consequently, the lower peak femoral blood flow estimates reported herein. As such, the peak femoral flows in the present study represent reasonable estimates of the hyperemic capacity of the contracting quadriceps in average fit, but non-exercise-trained women and men.

Conclusions.

Our findings indicate that systemic aerobic capacity (maximal cardiac output and V̇o2max) was positively correlated with peripheral vascular reserve, as measured by peak blood flow and conducting capacity of the contracting knee extensor muscles, in men but not women. This relationship was most pronounced in older men, regardless of how peripheral vasodilatory capacity was expressed or normalized. The disparate balance between maximal cardiac output and peripheral vascular reserve suggests different cardiovascular regulatory mechanisms and/or limitations during whole body exercise in men and women, particularly with aging.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG-018246 (to D. N. Proctor) and Division of Research Resources Grant M01 RR-10732 (to GCRC).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants, Ian McKelvey for assistance with data collection, Allen Kunselman for assistance with statistical analysis, and the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at University Park for assistance with subject screening and clinical support.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersen P, Saltin B. Maximal perfusion of skeletal muscle in man. J Physiol 366: 233–249, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bell C, Monahan KD, Donato AJ, Hunt BE, Seals DR, Beck KC. Use of acetylene breathing to determine cardiac output in young and older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 58–64, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clausen JP. Effect of physical training on cardiovascular adjustments to exercise in man. Physiol Rev 57: 779–815, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleg JL, O'Connor F, Gerstenblith G, Becker LC, Clulow J, Schulman SP, Lakatta EG. Impact of age on the cardiovascular response to dynamic upright exercise in healthy men and women. J Appl Physiol 78: 890–900, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu Q, Iwase S, Niimi Y, Kamiya A, Michikami D, Mano T. Effects of aging on leg vein filling and venous compliance during low levels of lower body negative pressure in humans. Environ Med 43: 142–145, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fu Q, Witkowski S, Okazaki K, Levine BD. Effects of gender and hypovolemia on sympathetic neural responses to orthostatic stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R109–R116, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hagberg JM, Allen WK, Seals DR, Hurley BF, Ehsani AA, Holloszy JO. A hemodynamic comparison of young and older endurance athletes during exercise. J Appl Physiol 58: 2041–2046, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harper AJ, Ferreira LF, Lutjemeier BJ, Townsend DK, Barstow TJ. Human femoral artery and estimated muscle capillary blood flow kinetics following the onset of exercise. Exp Physiol 91: 661–671, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG, Curry TB, Eisenach JH, Joyner MJ. Sex differences in sympathetic neural-hemodynamic balance: implications for human blood pressure regulation. Hypertension 53: 571–576, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hart EC, Joyner MJ, Wallin BG, Johnson CP, Curry TB, Eisenach JH, Charkoudian N. Age-related differences in the sympathetic-hemodynamic balance in men. Hypertension 54: 127–133, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hepple RT, Babits TL, Plyley MJ, Goodman JM. Dissociation of peak vascular conductance and V̇o2max among highly trained athletes. J Appl Physiol 87: 1368–1372, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoelting BD, Scheuermann BW, Barstow TJ. Effect of contraction frequency on leg blood flow during knee extension exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 91: 671–679, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hossack KF, Bruce RA. Maximal cardiac function in sedentary normal men and women: comparison of age-related changes. J Appl Physiol 53: 799–804, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson BD, Beck KC, Proctor DN, Miller J, Dietz NM, Joyner MJ. Cardiac output during exercise by the open circuit acetylene washin method: comparison with direct Fick. J Appl Physiol 88: 1650–1658, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jondeau G, Katz SD, Toussaint JF, Dubourg O, Monrad ES, Bourdarias JP, LeJemtel TH. Regional specificity of peak hyperemic response in patients with congestive heart failure: correlation with peak aerobic capacity. J Am Coll Cardiol 22: 1399–1402, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones PR, Pearson J. Anthropometric determination of leg fat and muscle plus bone volumes in young male and female adults. J Physiol 204: 63P–66P, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kosmas EN, Hussain SA, Montserrat JM, Levy RD. Relationship of peak exercise capacity with indexes of peripheral muscle vasodilation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28: 1254–1259, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lawrenson L, Poole JG, Kim J, Brown C, Patel P, Richardson RS. Vascular and metabolic response to isolated small muscle mass exercise: effect of age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1023–H1031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacDonald MJ, Shoemaker JK, Tschakovsky ME, Hughson RL. Alveolar oxygen uptake and femoral artery blood flow dynamics in upright and supine leg exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 1622–1628, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magnusson G, Kaijser L, Isberg B, Saltin B. Cardiovascular responses during one- and two-legged exercise in middle-aged men. Acta Physiol Scand 150: 353–362, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Magnusson G, Kaijser L, Sylven C, Karlberg KE, Isberg B, Saltin B. Peak skeletal muscle perfusion is maintained in patients with chronic heart failure when only a small muscle mass is exercised. Cardiovasc Res 33: 297–306, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin WH, 3rd, Montgomery J, Snell PG, Corbett JR, Sokolov JJ, Buckey JC, Maloney DA, Blomqvist CG. Cardiovascular adaptations to intense swim training in sedentary middle-aged men and women. Circulation 75: 323–330, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin WH, 3rd, Ogawa T, Kohrt WM, Malley MT, Korte E, Kieffer PS, Schechtman KB. Effects of aging, gender, and physical training on peripheral vascular function. Circulation 84: 654–664, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Narkiewicz K, Phillips BG, Kato M, Hering D, Bieniaszewski L, Somers VK. Gender-selective interaction between aging, blood pressure, and sympathetic nerve activity. Hypertension 45: 522–525, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogawa T, Spina RJ, Martin WH, 3rd, Kohrt WM, Schechtman KB, Holloszy JO, Ehsani AA. Effects of aging, sex, and physical training on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Circulation 86: 494–503, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parker BA, Smithmyer SL, Jarvis SS, Ridout SJ, Pawelczyk JA, Proctor DN. Evidence for reduced sympatholysis in leg resistance vasculature of healthy older women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1148–H1156, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parker BA, Smithmyer SL, Pelberg JA, Mishkin AD, Herr MD, Proctor DN. Sex differences in leg vasodilation during graded knee extensor exercise in young adults. J Appl Physiol 103: 1583–1591, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parker BA, Smithmyer SL, Pelberg JA, Mishkin AD, Proctor DN. Sex-specific influence of aging on exercising leg blood flow. J Appl Physiol 104: 655–664, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Proctor DN, Le KU, Ridout SJ. Age and regional specificity of peak limb vascular conductance in men. J Appl Physiol 98: 193–202, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radegran G. Ultrasound Doppler estimates of femoral artery blood flow during dynamic knee extensor exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 83: 1383–1388, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reading JL, Goodman JM, Plyley MJ, Floras JS, Liu PP, McLaughlin PR, Shephard RJ. Vascular conductance and aerobic power in sedentary and active subjects and heart failure patients. J Appl Physiol 74: 567–573, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Snell PG, Martin WH, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG. Maximal vascular leg conductance in trained and untrained men. J Appl Physiol 62: 606–610, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. White M, Courtemanche M, Stewart DJ, Talajic M, Mikes E, Cernacek P, Vantrimpont P, Leclerc D, Bussieres L, Rouleau JL. Age- and gender-related changes in endothelin and catecholamine release, and in autonomic balance in response to head-up tilt. Clin Sci (Lond) 93: 309–316, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]