Primary care globally deals with the whole spectrum of mental disorder from minor to severe mental illness depending on the systems and specialist expertise available, and the prevalence of mental disorders in primary care settings has been researched extensively in a range of different countries.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 154 million people suffer from depression and 25 million people from schizophrenia.1

The principal mental disorders presenting in primary care settings are depression (ranging from 5% to 20%), generalised anxiety disorder (4–15%), harmful alcohol use and dependence (5–15%) and somatisation disorders (0.5–11%).1

It is important to note that over recent years the word ‘depression’ has been used extremely widely to describe a large number of different presentations as a result of matching the presenting symptoms to diagnostic criteria, according to the recognised ICD‐10 or DSM‐IV classification tools.2,3 Sometimes in insurance‐based healthcare systems it is important to meet ICD‐10 and DSM‐IV criteria to make claims for treatment. This may also lead to more presentations being classified under the umbrella term ‘depression’ rather than a primary care symptom‐based approach such as the ICPC being used.4

From my own experience as a practicing practical primary care clinician, it is important to be able to code sub‐threshold mental health conditions and uncertainty instead of jumping to a definitive diagnosis of depression.

Coping with uncertainty is part of the art of working in primary care and the management of uncertainty makes the family physician unique, especially as a large proportion of presentations resolve with minimal support, encouragement, health education and promotion of normality. It is therefore important not to label all emotional conditions as disorders as they may simply be adaptive.

The literature suggests that depression is a very common disorder which seems to be occurring more frequently as, according to WHO data, it will very soon be the most frequent cause of morbidity after cardiovascular diseases.5 Although primary care colleagues are increasingly confident in making the diagnosis of depression, it is necessary to reflect on what these statistics represent. I would like to propose another view for us to consider. Could these statistics represent the overconfidence of clinicians in making the diagnosis of depression as, from my clinical experience and that of some of my colleagues in Spain, some of those people diagnosed as suffering from depression may in fact be suffering from adaptive emotional distress from which they would have made a spontaneous recovery.

Mild depression is a frequent diagnosis in primary care. Differentiation between mild depression as an illness requiring treatment and adaptive mood disorder is not always easy to make, especially if the clinician is not familiar with the wider spectrum of diagnoses and sub‐syndromes identifiable in primary care which have been categorised using the ICPC.4 Many patients who consult primary care clinicians present with multiple life events within a sociological context and their presentations may be emotionally based.

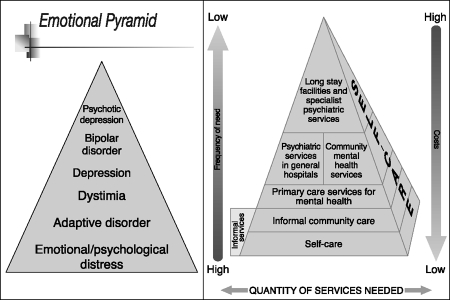

Let me now reflect on this observation. Figure 1 depicts an emotional‐based diagnostic pyramid. The base represents day‐to‐day emotional distress resulting from many causes. The apex represents the severe end of the emotional spectrum and includes bipolar disorders and psychotic depression. The emotional pyramid can be related to resource utilisation in which the base represents self care and the apex access to specialist mental health services (see Figure 1).1 Many people who suffer from emotional distress may simply benefit from self care and may not access any formal care network. This may be one of the reasons why primary care clinicians are not confident in making a diagnosis of emotional distress, because they are not familiar with the course of these episodes due to their lack of exposure to these adaptive conditions.

Figure 1.

The emotional pyramid and WHO‐Wonca pyramid of health access

Emotional distress is very seldom considered as a diagnostic entity, however, a framework does exist in the ICD‐10 classification system which contains ‘Z’ codes.2 Z codes cover a large range of conditions that do not reach the criteria for an ICD‐10 diagnosis of depressive disorder but may cover states of emotional distress that present to the primary care clinician. An example of a Z code classification can be found in Chapter XXI ‘Persons with potential health hazards related to socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances (Z)’ and includes the following:

Problems related to education and literacy (Z 55)

Problems related to employment and unemployment (Z56)

Problems related to housing and economic circumstances (Z59)

Problems related to social environment (Z60)

Problems related to negative life events in childhood (Z61) and

Problems related to primary support group, including family circumstances (Z63).2

Using this as a conceptual framework for making a primary care diagnosis, a person presenting to the primary care physician as a result of emotional distress because of problems at work, the symptoms of which do not reach the threshold for a diagnosis of ICD‐10 depression, could be classified using Z56.5 to describe a person who feels stressed as a result of their employment status but who does not suffer from depressive disorder.

Some of the issues that that I would like us to reflect upon, especially with the current review of the classification system and the implications this has for healthcare funding, include:

Should healthcare providers deal with all the emotional problems that present in primary care that do not reach the threshold for a recognised mood disorder?

Are patients overmedicalising adaptive emotional symptoms?

I am speculating that one of the reasons for the overdiagnosis of depression could be the availability of antidepressant medications with alleged good safety profiles. And sometimes there is a need for physicians to feel that they are caring by taking action, even though the patient would have recovered fully with time.

Some healthcare centres lack time, skills and resources (such as access to psychological therapies) which may result in the overuse of pharmacological interventions in primary and secondary care settings.6 To start to address these problems the Wonca Working Party on Mental Health is promoting a primary care approach strategy named ‘Look, listen and test’7 an easy technique for mental state assessment in general practice.

Family physicians have witnessed a very difficult situation in which they are assumed to be someone who has the key to avoiding the emotional distress of daily life through medical intervention.

For someone suffering from emotional distress, coping with it should be something to learn from in different ways. In my opinion, being health agents in the primary care environment gives family physicians a unique position and a wide range of possibilities for providing psychological and behavioural help of the best kind.

Although there are already some studies, further studies are required to demonstrate the relevance of emotional distress (not depression) because of its potential impact on morbidity and mortality.8–10

Once we are confident about the real impact of emotional distress we will not have the unconscious need of both health professionals and the population to talk about depression, as we will be able to openly discuss the life problems which themselves cause different levels of emotional distress. Experience has shown that this will lead to increased satisfaction.11

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO and World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca) Integrating Mental Health into Primary Care: a global perspective. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th revision. 2007 version. www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic criteria from DSM‐IV‐TM (4e) Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamberts H, Woods M.(eds) International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Mental Health: depression. www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo‐Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta‐analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Medicine 2008;5:260–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivbijaro G, Kolkiewicz l, Palazidou E, Parmentier H. Look listen and test mental health assessment: the Wonca Culturally Sensitive Depression Guidelines. Primary Care Mental Health 2005;3:145–7 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross R, Tabenkin H, Brammli‐Greenberg S, Benbassat J. The association between inquiry about emotional distress and women's satisfaction with their family physician: findings from a national survey. Women and Health 2007;45:51–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinowitz J, Shayevitz D, Hornik T, Feldman D. Primary care physicians' detection of psychological distress among elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2005;13:773–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frostholm L, Fink P, Christensen KS, et al. The patients' illness perceptions and the use of primary health care. Psychosomatic Medicine 2005;67:997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross R, Brammli‐Greenberg S, Tabenkin H, Benbassat J. Primary care physicians' discussion of emotional distress and patient satisfaction. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 2007;37:331–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]