The scientific ‘battle’ (for the optimal reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction) between pharmaco-oriented and balloon-oriented cardiologists has already lasted 16 years. Tarantini et al.,1 in a meta-analysis, have suggested a sophisticated mathematical equation to calculate the acceptable primary percutaneous coronary intervention (p-PCI)-related delay [(compared with thrombolysis (TL)] for individual patients presenting with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). This newly proposed equation is based on the three main independent predictors of 30-day survival: (i) baseline mortality risk; (ii) presentation delay risk; and (iii) p-PCI (vs. TL) delay.

Tarantini's calculations showed that when the baseline mortality risk is 4%, the acceptable p-PCI (vs. TL) delay is only 35 min. Patients with higher baseline risk do benefit from a p-PCI strategy even when the transport times are extremely long: with 10% baseline risk the acceptable p-PCI delay is 153 min; with a baseline risk of 18% the acceptable p-PCI delay is (theoretically calculated) even >5 h (!).

This result supports the widespread use of p-PCI and almost total abandonment of TL. For >80% of the European population, a cath-lab with a PCI programme is available within 30 min transport distance. It is ‘just’ a matter of appropriate organization of the regional networks: >80% of STEMI patients can be treated by p-PCI—as has been clearly demonstrated in several European countries.2 This study showed that over half of the European countries are already able to provide p-PCI services to the vast majority of STEMI patients. TL should be used only in sparsely populated regions with extremely long transfer distances (e.g. remote Norwegian fjords and mountains, Greek islands, Alaska, etc.). However, even in these remote regions, TL should be used ‘en route’ to a p-PCI centre, as was recently shown by the NORDISTEMI study.3

Tarantini et al.1 concluded that ‘patients with a mortality risk <4.5% are unlikely to obtain a survival benefit by p-PCI compared with TL’. This is, however, an oversimplification. It was repeatedly shown that even patients with low mortality risk (e.g. young patients with inferior STEMI) have better outcomes with p-PCI compared with TL. The apparent lack of benefit (from p-PCI) is caused only by the lack of statistical power in low risk subgroups. Concerning the baseline risk, there is no single subgroup of STEMI patients showing benefit from TL compared with p-PCI. Patients in all baseline risk subgroups do benefit from p-PCI; the statistical power of this benefit is weak in low risk subgroups due to mathematical (not medical) reasons. While the absolute mortality difference (p-PCI vs. TL) decreases with decreasing baseline risk, the relative mortality benefit from p-PCI remains similar across all baseline risk subgroups.

Many discussions about p-PCI and TL omit four important problems:

The time mismatch. The time delay of p-PCI (compared with TL) is usually calculated as the difference between door-to-needle time (TL) and door-to-balloon time (p-PCI). This is wrong in principle, because it is comparison of time to the start of treatment (TL) vs. time to the effect (reperfusion) of a treatment (p-PCI). This is a comparison of apples vs. oranges. If the realistic time to reperfusion were to be analysed, one should add at least 30 min (probably 60 min would be even more appropriate) on top of the door-to-needle time in thrombolysed patients. Also, this 30 min delay is similar to the usual sheath-to-balloon time in a p-PCI setting. In other words, because we do not know the exact time of reperfusion in TL, a comparison of door-to-needle time (TL) vs. door-to-sheath time (p-PCI) would be a much fairer method to compare the reperfusion therapies.

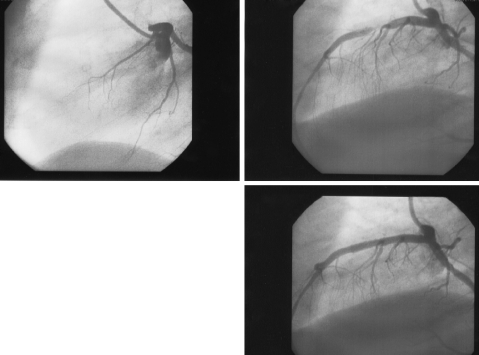

Different effectiveness. TL is effective in 40–60% of patients, while p-PCI is effective in ∼90%. Thus, comparing TL vs. p-PCI is comparing a semi-effective therapy vs. a fully effective therapy. The mortality benefit derived from the p-PCI strategy is not related to the fact that the underlying stenosis is removed (Figure 1). The mortality benefit of p-PCI is caused by the simple fact that p-PCI is twice as effective as TL in opening the artery.

Uncertain thrombosis onset. The presentation delay (frequently used to stratify patients between p-PCI and TL therapy4,5) is based on the patient's subjective medical history. It was nicely shown by Rittersma6 that coronary thrombi are substantially older (from several hours up to a few weeks) than the subjective history indicates. Thus, the presentation delay is the weakest predictor of the ultimate outcome—as was well demonstrated in the study of Tarantini et al.1

Facilitated PCI was abandoned due to the results of several randomized trials.7–10 However, the proportion of patients with really long transport times was very low in these trials. Two other trials3,11 suggest that for remote regions with very long transport distances, the pharmacomechanic approach may be valid.

Age and Killip class are two main baseline risk factors predicting the 30 day outcome in STEMI.12 Thus, if we want to implement the suggestions of Tarantini practically, we end up with the following recommendation: all patients >65 years of age13 and all patients presenting in Killip class >I should be treated by p-PCI. Patients <65 years presenting in Killip class I should also be treated by p-PCI unless the p-PCI-related delay is substantially longer than 35 min. For this subgroup (young patients without signs of acute heart failure), TL remains a very good option in remote regions with long transfer distances or in places with suboptimal organization of STEMI patient care.

Figure 1.

Left anterior descending coronary artery in a patient with STEMI. Upper left: proximal occlusion. Upper right: reperfusion after thrombolysis with significant residual stenosis. Lower: reperfusion after primary PCI without any residual stenosis.

The widespread (everywhere) use of Tarantini's equation for individual patients would add unnecessary complexity on the pre-hospital STEMI care in most regions, where p-PCI is available and should be applied to all STEMI patients. The suggested calculation is an ideal solution for sparsely populated regions with long transfer distances or for regions with suboptimal patient care organization.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Tarantini G, Razzolini R, Napodano M, Bilato C, Ramondo A, Iliceto S. Acceptable reperfusion delay to prefer primary angioplasty over fibrin-specific thrombolytic therapy is affected (mainly) by the patient's mortality risk: 1 h does not fit all. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:676–683. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp506. First published on 27 November 2009. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, De Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, Andrikopoulos G, Baz JA, Betriu A, Claeys M, Danchin N, Djambazov S, Erne P, Hartikainen J, Huber K, Kala P, Klinceva M, Dalby Kristensen S, Ludman P, Mauri Ferre J, Merkely B, Miličić D, Morais J, Noč M, Opolski G, Ostojić M, Radovanovič D, De Servi S, Stenestrand U, Studenčan M, Tubaro M, Vasiljević Z, Weidinger F, Witkowski A, Zeymer U on behalf of the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe. Description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2009 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp492. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp492, epub ahead of print 19 November 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohmer E, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Mangschau A, Hoffmann P, Halvorsen S. The NORwegian study on DIstrict treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NORDISTEMI) Scand Cardiovasc J. 2007;41:32–38. doi: 10.1080/14017430601153472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Silber S, Aguirre FV, Al-Attar N, Alegria E, Andreotti F, Benzer W, Breithardt O, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Dudek D, Gulba D, Halvorsen S, Kaufmann P, Kornowski R, Lip GY, Rutten F ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widimský P., Janoušek S., Vojáček J on behalf of the Czech Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Cor Vasa. 2002;44:K123–K143. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rittersma SZH, van der Wal AC, Koch KT, Piek JJ, Henriques JPS, Mulder KJ, Ploegmakers JPHM, Meesterman M, de Winter RJ. Plaque instability frequently occurs days or weeks before occlusive coronary thrombosis—a pathological thrombectomy study in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2005;111:1160–1165. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157141.00778.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis SG, Tendera M, de Belder MA, van Boven AJ, Widimsky P, Janssens L, Andersen HR, Betriu A, Savonitto S, Adamus J, Peruga JZ, Kosmider M, Katz O, Neunteufl T, Jorgova J, Dorobantu M, Grinfeld L, Armstrong P, Brodie BR, Herrmann HC, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Effron MB, Barnathan ES, Topol EJ FINESSE Investigators. Facilitated PCI in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2205–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Treatment Strategy with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ASSENT- 4 PCI) investigators. Primary versus tenecteplase facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST- elevation acute myocardial Infarction: the ASSENT-4 PCI randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widimský P, Groch L, Zelízko M, Aschermann M, Bednár F, Suryapranata H. Multicentre randomized trial comparing transport to primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis vs combined strategy for patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting to a community hospital without a catheterization laboratory. The PRAGUE study. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:823–831. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeer F, Oude Ophuis AJ, van der Berg EJ, Brunninkhuis LG, Werter CJ, Boehmer AG, Lousberg AH, Dassen WR, Bär FW. Prospective randomised comparison between thrombolysis, rescue PTCA, and primary PTCA in patients with extensive myocardial infarction admitted to a hospital without PTCA facilities: a safety and feasibility study. Heart. 1999;82:426–431. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.4.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Mario C, Dudek D, Piscione F, Mielecki W, Savonitto S, Murena E, Dimopoulos K, Manari A, Gaspardone A, Ochala A, Zmudka K, Bolognese L, Steg PG, Flather M CARESS-in-AMI (Combined Abciximab RE-teplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the Combined Abciximab REteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI): an open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008;371:559–568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widimský P, Motovská Z, Bílková D, Aschermann M, Groch L, Želízko M. The impact of age and Killip class on outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Insight from the PRAGUE-1 and -2 trials and Registry. EuroIntervention. 2007;2:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto DS, Kirtane AJ, Nallamothu BK, Murphy SA, Cohen DJ, Laham RJ, Cutlip DE, Bates ER, Frederick PD, Miller DP, Carrozza JP, Jr, Antman EM, Cannon CP, Gibson CM. Hospital delays in reperfusion for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: implications when selecting a reperfusion strategy. Circulation. 2006;114:2019–2025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]