Friedrich Miescher, the Swiss scientist who discovered DNA in 1869, already understood a surprising amount about its function. Sadly, as Ralf Dahm explains, he fell short of grasping the role of DNA in heredity because he was held back by established theories of the time.

Friedrich Miescher's attempts to uncover the function of DNA

It might seem as though the role of DNA as the carrier of genetic information was not realized until the mid-1940s, when Oswald Avery (1877–1955) and colleagues demonstrated that DNA could transform bacteria (Avery et al, 1944). Although these experiments provided direct evidence for the function of DNA, the first ideas that it might have an important role in processes such as cell proliferation, fertilization and the transmission of heritable traits had already been put forward more than half a century earlier. Friedrich Miescher (1844–1895; Fig 1), the Swiss scientist who discovered DNA in 1869 (Miescher, 1869a), developed surprisingly insightful theories to explain its function and how biological molecules could encode information. Although his ideas were incorrect from today's point of view, his work contains concepts that come tantalizingly close to our current understanding. But Miescher's career also holds lessons beyond his scientific insights. It is the story of a brilliant scientist well on his way to making one of the most fundamental discoveries in the history of science, who ultimately fell short of his potential because he clung to established theories and failed to follow through with the interpretation of his findings in a new light.

…a brilliant scientist well on his way to making one of the most fundamental discoveries in the history of science […] fell short of his potential because he clung to established theories…

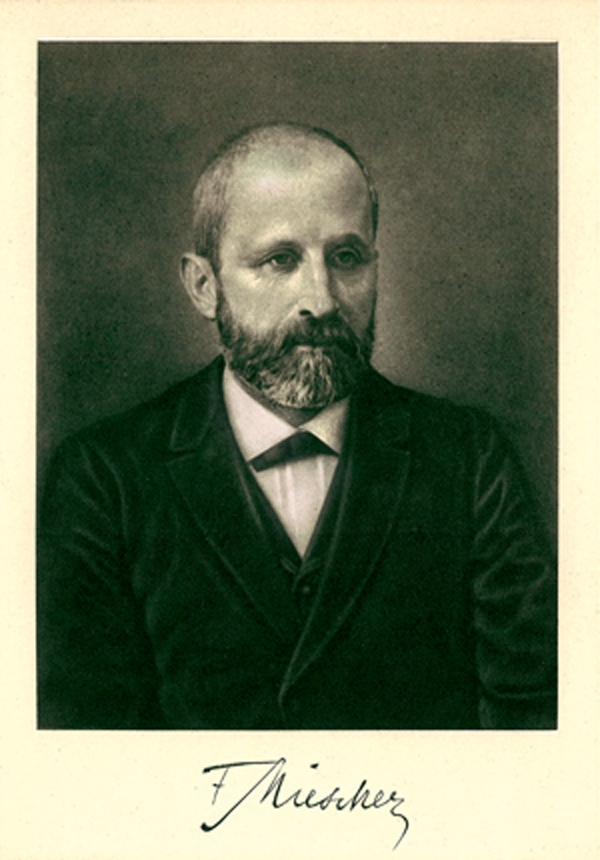

Figure 1.

Friedrich Miescher (1844–1895) and his wife, Maria Anna Rüsch. © Library of the University of Basel, Switzerland.

It is a curious coincidence in the history of genetics that three of the most decisive discoveries in this field occurred within a decade: in 1859, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, in which he expounded the mechanism driving the evolution of species; seven years later, Gregor Mendel's (1822–1884) paper describing the basic laws of inheritance appeared; and in early 1869, Miescher discovered DNA. Yet, although the magnitude of Darwin's theory was realized almost immediately, and at least Mendel himself seems to have grasped the importance of his work, Miescher is often viewed as oblivious to the significance of his discovery. It would be another 75 years before Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod (1909–1972) and Maclyn McCarthy (1911–2005) could convincingly show that DNA was the carrier of genetic information, and another decade before James Watson and Francis Crick (1916–2004) unravelled its structure (Watson & Crick, 1953), paving the way to our understanding of how DNA encodes information and how this is translated into proteins. But Miescher already had astonishing insights into the function of DNA.

Between 1868 and 1869, Miescher worked at the University of Tübingen in Germany (Figs 2,3), where he tried to understand the chemical basis of life. A crucial difference in his approach compared with earlier attempts was that he worked with isolated cells—leukocytes that he obtained from pus—and later purified nuclei, rather than whole organs or tissues. The innovative protocols he developed allowed him to investigate the chemical composition of an isolated organelle (Dahm, 2005), which significantly reduced the complexity of his starting material and enabled him to analyse its constituents.

Figure 2.

Contemporary view of the town of Tübingen at about the time when Miescher worked there. The medieval castle housing Hoppe-Seyler's laboratory can be seen atop the hill at the right. © Stadtarchiv Tübingen, Germany.

Figure 3.

The former kitchen of Tübingen castle, which formed part of Hoppe-Seyler's laboratory. It was in this room that Miescher worked during his stay in Tübingen and where he discovered DNA. After his return to Basel, Miescher reminisced how this room with its shadowy, vaulted ceiling and its small, deep-set windows appeared to him like the laboratory of a medieval alchemist. Photograph taken by Paul Sinner, Tübingen, in 1879. © University Library Tübingen.

In carefully designed experiments, Miescher discovered DNA—or “Nuclein” as he called it—and showed that it differed from the other classes of biological molecule known at that time (Miescher, 1871a). Most notably, nuclein's elementary composition with its high phosphorous content convinced him that he had discovered a substance sui generis, that is, of its own kind; a conclusion subsequently confirmed by Miescher's mentor in Tübingen, the eminent biochemist Felix Hoppe-Seyler (1825–1895; Hoppe-Seyler, 1871; Miescher, 1871a). After his initial analyses, Miescher was convinced that nuclein was an important molecule and suggested in his first publication that it would “merit to be considered equal to the proteins” (Miescher, 1871a).

Moreover, Miescher recognized immediately that nuclein could be used to define the nucleus (Miescher, 1870). This was an important realization, as at the time the unequivocal identification of nuclei, and hence their study, was often difficult or even impossible to achieve because their morphology, subcellular localization and staining properties differed between tissues, cell types and states of the cells. Instead, Miescher proposed to base the characterization of nuclei on the presence of this molecule (Miescher, 1870, 1874). Moreover, he held that the nucleus should be defined by properties that are related to its physiological activity, which he believed to be closely linked to nuclein. Miescher had thus made a significant first step towards defining an organelle in terms of its function rather than its appearance.

Importantly, his findings also showed that the nucleus is chemically distinct from the cytoplasm at a time when many scientists still assumed that there was nothing unique about this organelle. Miescher thus paved the way for the subsequent realization that cells are subdivided into compartments with distinct molecular composition and functions. On the basis of his observations that nuclein appeared able to separate itself from the “protoplasm” (cytoplasm), Miescher even went so far as to suggest the “possibility that [nuclein can be] distributed in the protoplasm, which could be the precursor for some of the de novo formations of nuclei” (Miescher, 1874). He seemed to anticipate that the nucleus re-forms around the chromosomes after cell division, but unfortunately did not elaborate on under which conditions this might occur. It is therefore impossible to know with certainty to which circumstances he was referring.

Miescher thus paved the way for the subsequent realization that cells are subdivided into compartments with distinct molecular composition and functions

In this context, it is interesting to note that in 1872, Edmund Russow (1841–1897) observed that chromosomes appeared to dissolve in basic solutions. Intriguingly, Miescher had also found that he could precipitate nuclein by using acids and then return it to solution by increasing the pH (Miescher, 1871a). At the time, however, he did not make the link between nuclein and chromatin. This happened around a decade later, in 1881, when Eduard Zacharias (1852–1911) studied the nature of chromosomes by using some of the same methods Miescher had used when characterizing nuclein. Zacharias found that chromosomes, such as nuclein, were resistant to digestion by pepsin solutions and that the chromatin disappeared when he extracted the pepsin-treated cells with dilute alkaline solutions. This led Walther Flemming (1843–1905) to speculate in 1882 that nuclein and chromatin are identical (Mayr, 1982).

Alas, Miescher was not convinced. His reluctance to accept these developments was at least partly based on a profound scepticism towards the methods—and hence results—of cytologists and histologists, which, according to Miescher, lacked the precision of chemical approaches as he applied them. The fact that DNA was crucially linked to the function of the nucleus was, however, firmly established in Miescher's mind and in the following years he tried to obtain additional evidence. He later wrote: “Above all, using a range of suitable plant and animal specimens, I want to prove that Nuclein really specifically belongs to the life of the nucleus” (Miescher, 1876).

Although the acidic nature of DNA, its large molecular weight, elementary composition and presence in the nucleus are some of its central properties—all first determined by Miescher—they reveal nothing about its function. Having convinced himself that he had discovered a new type of molecule, Miescher rapidly set out to understand its role in different biological contexts. As a first step, he determined that nuclein occurs in a variety of cell types. Unfortunately, he did not elaborate on the types of tissue or the species his samples were derived from. The only hints as to the specimens he worked with come from letters he wrote to his uncle, the Swiss anatomist Wilhelm His (1831–1904), and his parents; his father, Friedrich Miescher-His (1811–1887), was professor of anatomy in Miescher's native Basel. In his correspondence, Miescher mentioned other cell types that he had studied for the presence of nuclein, including liver, kidney, yeast cells, erythrocytes and chicken eggs, and hinted at having found nuclein in these as well (Miescher, 1869b; His, 1897). Moreover, Miescher had also planned to look for nuclein in plants, especially in their spores (Miescher, 1869c). This is an intriguing choice given his later fascination with vertebrate germ cells and his speculation on the processes of fertilization and heredity (Miescher, 1871b, 1874).

Another clue to the tissues and cell types that Miescher might have examined comes from two papers published by Hoppe-Seyler, who wanted to confirm his student's results, which he initially viewed with scepticism, before their publication. In the first, another of Hoppe-Seyler's students, Pal Plósz, reported that nuclein is present in the nucleated erythrocytes of snakes and birds but not in the anuclear erythrocytes of cows (Plósz, 1871). In the second paper, Hoppe-Seyler himself confirmed Miescher's findings and reported that he had detected nuclein in yeast cells (Hoppe-Seyler, 1871).

In an addendum to his 1871 paper, published posthumously, Miescher stated that the apparently ubiquitous presence of nuclein meant that “a new factor has been found for the life of the most basic as well as for the most advanced organisms,” thus opening up a wide range of questions for physiology in general (Miescher, 1870). To argue that Miescher understood that DNA was an essential component of all forms of life is probably an over-interpretation of his words. His statement does, however, clearly show that he believed DNA to be an important factor in the life of a wide range of species.

In addition, Miescher looked at tissues under different physiological conditions. He quickly noticed that both nuclein and nuclei were significantly more abundant in proliferating tissues; for instance, he noted that in plants, large amounts of phosphorous are found predominantly in regions of growth and that these parts show the highest densities of nuclei and actively proliferating cells (Miescher, 1871a). Miescher had thus taken the first step towards linking the presence of phosphorous—that is, DNA in this context—to cell proliferation. Some years later, while examining changes in the bodies of salmon as they migrate upstream to their spawning grounds, he noticed that he could, with minimal effort, purify large amounts of pure nuclein from the testes, as they were at the height of cell proliferation in preparation for mating (Miescher, 1874). This provided additional evidence for a link between proliferation and the presence of a high concentration of nuclein.

Miescher's most insightful comments on this issue, however, date from his time in Hoppe-Seyler's laboratory in Tübingen. He was convinced that histochemical analyses would lead to a much better understanding of certain pathological states than would microscopic studies. He also believed that physiological processes, which at the time were seen as similar, might turn out to be very different if the chemistry were better understood. As early as 1869, the year in which he discovered nuclein, he wrote in a letter to His: “Based on the relative amounts of nuclear substances [DNA], proteins and secondary degradation products, it would be possible to assess the physiological significance of changes with greater accuracy than is feasible now” (Miescher, 1869c).

Importantly, Miescher proposed three exemplary processes that might benefit from such analyses: “nutritive progression”, characterized by an increase in the cytoplasmic proteins and the enlargement of the cell; “generative progression”, defined as an increase in “nuclear substances” (nuclein) and as a preliminary phase of cell division in proliferating cells and possibly in tumours; and “regression”, an accumulation of lipids and degenerative products (Miescher, 1869c).

When we consider the first two categories, Miescher seems to have understood that an increase in DNA was not only associated with, but also a prerequisite for cell proliferation. Subsequently, cells that are no longer proliferating would increase in size through the synthesis of proteins and hence cytoplasm. Crucially, he believed that chemical analyses of such different states would enable him to obtain a more fundamental insight into the causes underlying these processes. These are astonishingly prescient insights. Sadly, Miescher never followed up on these ideas and, apart from the thoughts expressed in his letter, never published on the topic.

…Miescher seems to have understood that an increase in DNA was not only associated with, but also a prerequisite for cell proliferation

It is likely, however, that he had preliminary data supporting these views. Miescher was generally careful to base statements on facts rather than speculation. But, being a perfectionist who published only after extensive verification of his results, he presumably never pursued these studies to such a satisfactory point. It is possible his plans were cut short by leaving Hoppe-Seyler's laboratory to receive additional training under the supervision of Carl Ludwig (1816–1895) in Leipzig. While there, Miescher turned his attention to matters entirely unrelated to DNA and only resumed his work on nuclein after returning to his native Basel in 1871.

Crucially for these subsequent studies of nuclein, Miescher made an important choice: he turned to sperm as his main source of DNA. When analysing the sperm from different species, he noted that the spermatozoa, especially of salmon, have comparatively small tails and thus consist mainly of a nucleus (Miescher, 1874). He immediately grasped that this would greatly facilitate his efforts to isolate DNA at much higher purity (Fig 4). Yet, Miescher also saw beyond the possibility of obtaining pure nuclein from salmon sperm. He realized it also indicated that the nucleus and the nuclein therein might play a crucial role in fertilization and the transmission of heritable traits. In a letter to his colleague Rudolf Boehm (1844–1926) in Würzburg, Miescher wrote: “Ultimately, I expect insights of a more fundamental importance than just for the physiology of sperm” (Miescher, 1871c). It was the beginning of a fascination with the phenomena of fertilization and heredity that would occupy Miescher to the end of his days.

Figure 4.

A glass vial containing DNA purified by Friedrich Miescher from salmon sperm. © Alfons Renz, University of Tübingen, Germany.

Miescher had entered this field at a critical time. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the old view that cells arise through spontaneous generation had been challenged. Instead, it was widely recognized that cells always arise from other cells (Mayr, 1982). In particular, the development and function of spermatozoa and oocytes, which in the mid-1800s had been shown to be cells, were seen in a new light. Moreover, in 1866, three years before Miescher discovered DNA, Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) had postulated that the nucleus contained the factors that transmit heritable traits. This proposition from one of the most influential scientists of the time brought the nucleus to the centre of attention for many biologists. Having discovered nuclein as a distinctive molecule present exclusively in this organelle, Miescher realized that he was in an excellent position to make a contribution to this field. Thus, he set about trying to better characterize nuclein with the aim of correlating its chemical properties with the morphology and function of cells, especially of sperm cells.

His analyses of the chemical composition of the heads of salmon spermatozoa led Miescher to identify two principal components: in addition to the acidic nuclein, he found an alkaline protein for which he coined the term ‘protamin'; the name is still in use today; protamines are small proteins that replace histones during spermatogenesis. He further determined that these two molecules occur in a “salt-like, not an ether-like [that is, covalent] association” (Miescher, 1874). Following his meticulous analyses of the chemical composition of sperm, he concluded that, “aside from the mentioned substances [protamin and nuclein] nothing is present in significant quantity. As this is crucial for the theory of fertilization, I carry this business out as quantitatively as possible right from the beginning” (Miescher, 1872a). His analyses showed him that the DNA and protamines in sperm occur at constant ratios; a fact that Miescher considered “is certainly of special importance,” without, however, elaborating on what might be this importance. Today, of course, we know that proteins, such as histones and protamines, bind to DNA in defined stoichiometric ratios.

Miescher went on to analyse the spermatozoa of carp, frogs (Rana esculenta) and bulls, in which he confirmed the presence of large amounts of nuclein (Miescher, 1874). Importantly, he could show that nuclein is present in only the heads of sperm—the tails being composed largely of lipids and proteins—and that within the head, the nuclein is located in the nucleus (Miescher, 1874; Schmiedeberg & Miescher, 1896). With this discovery, Miescher had not only demonstrated that DNA is a constant component of spermatozoa, but also directed his attention to the sperm heads. On the basis of the observations of other investigators, such as those of Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905) concerning the morphology of spermatozoa in some myriapods and arachnids, Miescher knew that the spermatozoa of some species are aflagellate, that is, lack a tail. This confirmed that the sperm head, and thus the nucleus, was the crucial component. But, the question remained: what in the sperm cells mediated fertilization and the transmission of hereditary traits from one generation to the next?

On the basis of his chemical analyses of sperm, Miescher speculated on the existence of molecules that have a crucial part in these processes. In a letter to Boehm, Miescher wrote: “If chemicals do play a role in procreation at all, then the decisive factor is now a known substance” (Miescher, 1872b). But Miescher was unsure as to what might be this substance. He did, however, strongly suspect the combination of nuclein and protamin was the key and that the oocyte might lack a crucial component to be able to develop: “If now the decisive difference between the oocyte and an ordinary cell would be that from the roster of factors, which account for an active arrangement, an element has been removed? For otherwise all proper cellular substances are present in the egg,” he later wrote (Miescher, 1872b).

Owing to his inability to detect protamin in the oocyte, Miescher initially favoured this molecule as responsible for fertilization. Later, however, when he failed to detect protamin in the sperm of other species, such as bulls, he changed his mind: “The Nuclein by contrast has proved to be constant [that is, present in the sperm cells of all species Miescher analysed] so far; to it and its associations I will direct my interest from now on” (Miescher, 1872b). Unfortunately, however, although he came tantalizingly close, he never made a clear link between nuclein and heredity.

The final section of his 1874 paper on the occurrence and properties of nuclein in the spermatozoa of different vertebrate species is of particular interest because Miescher tried to correlate his chemical findings about nuclein with the physiological role of spermatozoa. He had realized that spermatozoa represented an ideal model system to study the role of DNA because, as he would later put it, “[f]or the actual chemical–biological problems, the great advantage of sperm [cells] is that everything is reduced to the really active substances and that they are caught just at the moment when they exert their greatest physiological function” (Miescher, 1893a). He appreciated that his data were still incomplete, yet wanted to make a first attempt to pull his results together and integrate them into a broader picture to explain fertilization.

At the time, Wilhelm Kühne (1837–1900), among others, was putting forward the idea that spermatozoa are the carriers of specific substances that, through their chemical properties, achieve fertilization (Kühne, 1868). Miescher considered his results of the chemical composition of spermatozoa in this context. While critically considering the possibility of a chemical substance explaining fertilization, he stated that: “if we were to assume at all that a single substance, as an enzyme or in any other way, for instance as a chemical impulse, could be the specific cause of fertilization, we would without a doubt first and foremost have to consider Nuclein. Nuclein-bodies were consistently found to be the main components [of spermatozoa]” (Miescher, 1874).

With hindsight, these statements seem to suggest that Miescher had identified nuclein as the molecule that mediates fertilization—a crucial assumption to follow up on its role in heredity. Unfortunately, however, Miescher himself was far from convinced that a molecule (or molecules) was responsible for this. There are several reasons for his reluctance, although the influence of his uncle was presumably a crucial factor as it was he who had been instrumental in fostering the young Miescher's interest in biochemistry and remained a strong influence throughout his life. Indeed, when Miescher came tantalizingly close to uncovering the function of DNA, His's views proved counterproductive, probably preventing him from interpreting his findings in the context of new results from other scientists at the time. Miescher thus failed to take his studies of nuclein and its function in fertilization and heredity to the next level, which might well have resulted in recognizing DNA as the central molecule in both processes.

One specific aspect that diverted Miescher from contemplating the role of nuclein in fertilization was a previous study in which he had erroneously identified the yolk platelets in chicken oocytes as a large number of nuclein-containing granules (Miescher, 1871b). This led him to conclude that the comparatively minimal quantitative contribution of DNA from a spermatozoon to an oocyte, which already contained so much more of the substance, could not have a significant impact on the latter's physiology. He therefore concluded that, “not in a specific substance can the mystery of fertilization be concealed. […] Not a part, but the whole must act through the cooperation of all its parts” (Miescher, 1874).

It is all the more unfortunate that Miescher had identified the yolk platelets in oocytes as nuclein-containing cells because he had realized that the presumed nuclein in these granules differed from the nuclein (that is, DNA) he had isolated previously from other sources, notably by its much higher phosphorous content. But influenced by His's strong view that these structures were genuine cells, Miescher saw his results in this light. Only several years later, based on results from his contemporaries Flemming and Eduard A. Strasburger (1844–1912) on the morphological properties of nuclei and their behaviour during cell divisions, and Albrecht Kossel's (1853–1927) discoveries about the composition of DNA (Portugal & Cohen, 1977), did Miescher revise his initial assumption that chicken oocytes contain a large number of nuclein-containing granules. Instead, he finally conceded that the molecules comprising these granules were different from nuclein (Miescher, 1890).

Another factor that prevented Miescher from concluding that nuclein was the basis for the transmission of hereditary traits was that he could not conceive of how a single substance might explain the multitude of heritable traits. How, he wondered, could a specific molecule be responsible for the differences between species, races and individuals? Although he granted that “differences in the chemical constitution of these molecules [different types of nuclein] will occur, but only to a limited extent” (Miescher, 1874).

And thus, instead of looking to molecules, he—like his uncle His––favoured the idea that the physical movement of the sperm cells or an activation of the oocyte, which he likened to the stimulation of a muscle by neuronal impulses, was responsible for the process of fertilization: “Like the muscle during the activation of its nerve, the oocyte will, when it receives appropriate impulses, become a chemically and physically very different entity” (Miescher, 1874). For nuclein itself, Miescher considered that it might be a source material for other molecules, such as lecithin––one of the few other molecules with a high phosphorous content known at the time (Miescher, 1870, 1871a, 1874). Miescher clearly preferred the idea of nuclein as a repository for material for the cell—mainly phosphorous—rather than as a molecule with a role in encoding information to synthesize such materials. This idea of large molecules being source material for smaller ones was common at the time and was also contemplated for proteins (Miescher, 1870).

The entire section of Miescher's 1874 paper in which he discusses the physiological role of nuclein reads as though he was deliberately trying to assemble evidence against nuclein being the key molecule in fertilization and heredity. This disparaging approach towards the molecule that he himself had discovered might also be explained, at least to some extent, by his pronounced tendency to view his results so critically; tellingly, he published only about 15 papers and lectures in a career spanning nearly three decades.

The modern understanding that fertilization is achieved by the fusion of two germ cells only became established in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. Before that time, the almost ubiquitous view was that the sperm cell, through mere contact with the egg, in some way stimulated the oocyte to develop—the physicalist viewpoint. His was a key advocate of this view and firmly rejected the idea that a specific substance might mediate heredity. We can only speculate as to how Miescher would have interpreted his results had he worked in a different intellectual environment at the time, or had he been more independent in the interpretation of his results.

We can only speculate as to how Miescher would have interpreted his results had he worked in a different intellectual environment at the time…

Miescher's refusal to accept nuclein as the key to fertilization and heredity is particularly tragic in view of several studies that appeared in the mid-1870s, focusing the attention of scientists on the nuclei. Leopold Auerbach (1828–1897) demonstrated that fertilized eggs contain two nuclei that move towards each other and fuse before the subsequent development of the embryo (Auerbach, 1874). This observation strongly suggested an important role for the nuclei in fertilization. In a subsequent study, Oskar Hertwig (1849–1922) confirmed that the two nuclei—one from the sperm cell and one from the oocyte—fuse before embryogenesis begins. Furthermore, he observed that all nuclei in the embryo derive from this initial nucleus in the zygote (Hertwig, 1876). With this he had established that a single sperm fertilizes the oocyte and that there is a continuous lineage of nuclei from the zygote throughout development. In doing so, he delivered the death blow to the physicalist view of fertilization.

By the mid-1880s, Hertwig and Kölliker had already postulated that the crucial component of the nucleus that mediated inheritance was nuclein—an idea that was subsequently accepted by several scientists. Sadly, Miescher remained doubtful until his death in 1895 and thus failed to appreciate the true importance of his discovery. This might have been an overreaction to the claims by others that sperm heads are formed from a homogeneous substance; Miescher had clearly shown that they also contain other molecules, such as proteins. Moreover, Miescher's erroneous assumption that nuclein occurred only in the outer shell of the sperm head resulted in his failure to realize that stains for chromatin, which stain the centres of the heads, actually label the region where there is nuclein; although he later realized that virtually the entire sperm head is composed of nuclein and associated protein (Miescher, 1892a; Schmiedeberg & Miescher, 1896).

Unfortunately, not only Miescher, but the entire scientific community would soon lose faith in DNA as the molecule mediating heredity. Miescher's work had established DNA as a crucial component of all cells and inspired others to begin exploring its role in heredity, but with the emergence of the tetranucleotide hypothesis at the beginning of the twentieth century, DNA fell from favour and was replaced by proteins as the prime candidates for this function. The tetranucleotide hypothesis—which assumed that DNA was composed of identical subunits, each containing all four bases—prevailed until the late 1940s when Edwin Chargaff (1905–2002) discovered that the different bases in DNA were not present in equimolar amounts (Chargaff et al, 1949, 1951).

Unfortunately, not only Miescher, but the entire scientific community would soon lose faith in DNA as the molecule mediating heredity

Just a few years before, in 1944, experiments by Avery and colleagues had demonstrated that DNA was sufficient to transform bacteria (Avery et al, 1944). Then in 1952, Al Hershey (1908–1997) and Martha Chase (1927–2003) confirmed these findings by observing that viral DNA—but no protein—enters the bacteria during infection with the T2 bacteriophage and, that this DNA is also present in new viruses produced by infected bacteria (Hershey & Chase, 1952). Finally, in 1953, X-ray images of DNA allowed Watson and Crick to deduce its structure (Watson & Crick, 1953) and thus enable us to understand how DNA works. Importantly, these experiments were made possible by advances in bacteriology and virology, as well as the development of new techniques, such as the radioactive labelling of proteins and nucleic acids, and X-ray crystallography—resources that were beyond the reach of Miescher and his contemporaries.

In later years (Fig 5), Miescher's attention shifted progressively from the role of nuclein in fertilization and heredity to physiological questions, such as those concerning the metabolic changes in the bodies of salmon as they produce massive amounts of germ cells at the expense of muscle tissue. Although he made important and seminal contributions to different areas of physiology, he increasingly neglected to explore his most promising line of research, the function of DNA. Only towards the end of his life did he return to this question and begin to reconsider the issue in a new light, but he achieved no further breakthroughs.

Figure 5.

Friedrich Miescher in his later years when he was Professor of Physiology at the University of Basel. In this capacity he also founded the Vesalianum, the University's Institute for Anatomy and Physiology, which was inaugurated in 1885. This photograph is the frontispiece on the inside cover of a collection of Miescher's publications and some of his letters, edited and published by his uncle Wilhelm His and colleagues after Miescher's death. Underneath the picture is Miescher's signature. © Ralf Dahm.

One area, however, where he did propose intriguing hypotheses—although without experimental data to support them—was the molecular underpinnings of heredity. Inspired by Darwin's work on fertilization in plants, Miescher postulated, for instance, how information might be encoded in biological molecules. He stated that, “the key to sexuality for me lies in stereochemistry,” and expounded his belief that the gemmules of Darwin's theory of pangenesis were likely to be “numerous asymmetric carbon atoms [present in] organic substances” (Miescher, 1892b), and that sexual reproduction might function to correct mistakes in their “stereometric architecture”. As such, Miescher proposed that hereditary information might be encoded in macromolecules and how mistakes could be corrected, which sounds uncannily as though he had predicted what is now known as the complementation of haploid deficiencies by wild-type alleles. It is particularly tempting to assume that Miescher might have thought this was the case, as Mendel had published his laws of inheritance of recessive characteristics more than 25 years earlier. However, there is no reference to Mendel's work in the papers, talks or letters that Miescher has left to us.

Miescher proposed that hereditary information might be encoded in macromolecules and how mistakes could be corrected…

What we do know is that Miescher set out his view of how hereditary information might be stored in macromolecules: “In the enormous protein molecules […] the many asymmetric carbon atoms allow such a colossal number of stereoisomers that all the abundance and diversity of the transmission of hereditary [traits] may find its expression in them, as the words and terms of all languages do in the 24–30 letters of the alphabet. It is therefore completely superfluous to see the sperm cell or oocyte as a repository of countless chemical substances, each of which should be the carrier of a special hereditary trait (de Vries Pangenesis). The protoplasm and the nucleus, that my studies have shown, do not consist of countless chemical substances, but of very few chemical individuals, which, however, perhaps have a very complex chemical structure” (Miescher, 1892b).

This is a remarkable passage in Miescher's writings. The second half of the nineteenth century saw intense speculation about how heritable characteristics are transmitted between the generations. The consensus view assumed the involvement of tiny particles, which were thought to both shape embryonic development and mediate inheritance (Mayr, 1982). Miescher contradicted this view. Instead of a multitude of individual particles, each of which might be responsible for a specific trait (or traits), his results had shown that, for instance, the heads of sperm cells are composed of only very few compounds, chiefly DNA and associated proteins.

He elaborated further on his theory of how hereditary information might be stored in large molecules: “Continuity does not only lie in the form, it also lies deeper than the chemical molecule. It lies in the constituent groups of atoms. In this sense I am an adherent of a chemical model of inheritance à outrance [to the utmost]” (Miescher, 1893b). With this statement Miescher firmly rejects any idea of preformation or some morphological continuity transmitted through the germ cells. Instead, he clearly seems to foresee what would only become known much later: the basis of heredity was to be found in the chemical composition of molecules.

To explain how this could be achieved, he proposed a model of how information could be encoded in a macromolecule: “If, as is easily possible, a protein molecule comprises 40 asymmetric carbon atoms, there will be 240, that is, approximately a trillion isomerisms [sic]. And this is only one of the possible types of isomerism [not considering other atoms, such as nitrogen]. To achieve the incalculable diversity demanded by the theory of heredity, my theory is better suited than any other. All manner of transitions are conceivable, from the imperceptible to the largest differences” (Miescher, 1893b).

Miescher's ideas about how heritable characteristics might be transmitted and encoded encapsulate several important concepts that have since been proven to be correct. First, he believed that sexual reproduction served to correct mistakes, or mutations as we call them today. Second, he postulated that the transmission of heritable traits occurs through one or a few macromolecules with complex chemical compositions that encode the information, rather than by numerous individual molecules each encoding single traits, as was thought at the time. Third, he foresaw that information is encoded in these molecules through a simple code that results in a staggeringly large number of possible heritable traits and thus explain the diversity of species and individuals observed.

Miescher's ideas about how heritable characteristics might be transmitted and encoded encapsulate several important concepts that have since been proven to be correct

It is a step too far to suggest that Miescher understood what DNA or other macromolecules do, or how hereditary information is stored. He simply could not have done, given the context of his time. His findings and hypotheses that today fit nicely together and often seem to anticipate our modern understanding probably appeared rather disjointed to Miescher and his contemporaries. In his day, too many facts were still in doubt and too many links tenuous. There is always a danger of over-interpreting speculations and hypotheses made a long time ago in today's light. However, although Miescher himself misinterpreted some of his findings, large parts of his conclusions came astonishingly close to what we now know to be true. Moreover, his work influenced others to pursue their own investigations into DNA and its function (Dahm, 2008). Although DNA research fell out of fashion for several decades after the end of the nineteenth century, the information gleaned by Miescher and his contemporaries formed the foundation for the decisive experiments carried out in the middle of the twentieth century, which unambiguously established the function of DNA.

As such, perhaps the most tragic aspect of Miescher's career was that for most of his life he firmly believed in the physicalist theories of fertilization, as propounded by His and Ludwig among others, and his reluctance to combine the results from his rigorous chemical analyses with the ‘softer' data generated by cytologists and histologists. Had he made the link between nuclein and chromosomes and accepted its key role in fertilization and heredity, he might have realized that the molecule he had discovered was the key to some of the greatest mysteries of life. As it was, he died with a feeling of a promising career unfulfilled (His, 1897), when, in actual fact, his contributions were to outshine those of most of his contemporaries.

…he died with a feeling of a promising career unfulfilled […] when, in actual fact, his contributions were to outshine those of most of his contemporaries

It is tantalizing to speculate the path that Miescher's investigations—and biology as a whole—might have taken under slightly different circumstances. What would have happened had he followed up on his preliminary results about the role of DNA in different physiological conditions, such as cell proliferation? How would his theories about fertilization and heredity have changed had he not been misled by the mistaken identification of what appeared to him to be a multitude of small nuclei in the oocyte? Or how would he have interpreted his findings concerning nuclein had he not been influenced by the views of his uncle, but also those of the wider scientific establishment?

There is a more general lesson in the life and work of Friedrich Miescher that goes beyond his immediate successes and failures. His story is that of a brilliant researcher who developed innovative experimental approaches, chose the right biological systems to address his questions and made ground-breaking discoveries, and who was nonetheless constrained by his intellectual environment and thus prevented from interpreting his findings objectively. It therefore fell to others, who saw his work from a new point of view, to make the crucial inferences and thus establish the function of DNA.

Ralf Dahm

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Nicholas S. Foulkes and Helia B. Schönthaler for critically reading this manuscript and for many insightful comments. The author is also indebted to Markus R. Schneller of the Max Planck Campus's library in Tübingen, Germany, for generous help in obtaining old publications, and to Johannes-Maria Schlorke for help with preparing Fig 4.

Footnotes

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Auerbach L (1874) Organologische Studien. Breslau, Germany: E. Morgenstein [Google Scholar]

- Avery OT, MacLeod CM, McCarty M (1944) Studies of the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types. Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus type III. J Exp Med 79: 137–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chargaff E, Vischer E, Doniger R, Green C, Misani F (1949) The composition of the desoxypentose nucleic acid of thymus and spleen. J Biol Chem 177: 405–416 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chargaff E, Lipshitz R, Green C, Hodes ME (1951) The composition of the deoxyribonucleic acid of salmon sperm. J Biol Chem 192: 223–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm R (2005) Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA. Dev Biol 278: 274–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm R (2008) Discovering DNA: Friedrich Miescher and the early years of nucleic acid research. Hum Genet 122: 565–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey AD, Chase M (1952) Independent functions of viral proteins and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol 36: 39–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig O (1876) Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Bildung, Befruchtung und Theilung des thierischen Eis. Morph Jahrbuch 1: 347–434 [Google Scholar]

- His W (1897) F. Miescher. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 5–32. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe-Seyler F (1871) Ueber die chemische Zusammensetzung des Eiters. Medicinisch-chemische Untersuchungen 4: 486–501 [Google Scholar]

- Kühne W (1868) Männliche Geschlechtsabsonderungen. In Lehrbuch der Physiologischen Chemie, pp 555–558. Leipzig, Germany: W. Engelmann [Google Scholar]

- Mayr E (1982) The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. Cambridge MA, USA: Belknap [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1869a) Letter I; to Wilhelm His; Tübingen, February 26th, 1869. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 33–38. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1869b) Letter IV; to Miescher's parents; Tübingen, August 21st, 1869. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, p 39. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1869c) Letter V; to Wilhelm His; Leipzig, December 20th, 1869. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 39–41. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1870) Nachträgliche Bemerkungen. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 2, pp 32–34. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1871a) Ueber die chemische Zusammensetzung der Eiterzellen. Medicinisch-chemische Untersuchungen 4: 441–460 [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1871b) Die Kerngebilde im Dotter des Hühnereies. Medicinisch-chemische Untersuchungen 4: 502–509 [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1871c) Letter XXV; to Dr Boehm in Würzburg; Basel, September 23rd, 1871. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 63–64. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1872a) Letter XXVI; to Felix Hoppe-Seyler; Basel, Summer 1872. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 64–68. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1872b) Letter XXVIII; to Dr Boehm; Basel, May 2nd, 1872. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 70–73. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1874) Die Spermatozoen einiger Wirbeltiere. Ein Beitrag zur Histochemie. Verhandlungen der naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Basel VI: 138–208 [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1876) Letter XLI; to Felix Hoppe-Seyler; June 25th, 1876. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 83–86. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1890) Biologische Studien über das Leben des Rheinlachses im Süsswasser. Vortrag, Gehalten vor der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Basel den 19 Februar 1890. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 2, pp 304–324. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1892a) Physiologische Fragmente über den Rheinlachs, vorgetragen in der medic. Section der schweizerischen naturf. Gesellschaft in Basel 6 Sept. 1892. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 2, pp 325–327. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1892b) Letter LXXV; to Wilhelm His; Basel, December 17th, 1892. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 116–117. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1893a) Letter LXXVI; to Wilhelm His; Basel, July 22nd, 1893. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 117–119. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Miescher F (1893b) Letter LXXVIII; to Wilhelm His; Basel, October 13th, 1893. In Die Histochemischen und Physiologischen Arbeiten von Friedrich Miescher – Aus dem Wissenschaftlichen Briefwechsel von F. Miescher, His W et al. (eds), Vol 1, pp 122–123. Leipzig, Germany: FCW Vogel [Google Scholar]

- Plósz P (1871) Ueber das chemische Verhalten der Kerne der Vogel- und Schlangenblutkörperchen. Medicinisch-chemische Untersuchungen 4: 461–462 [Google Scholar]

- Portugal FH, Cohen JS (1977) A Century of DNA. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedeberg O, Miescher F (1896) Physiologisch-chemische Untersuchungen über die Lachsmilch. Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 37: 100–155 [Google Scholar]

- Watson JD, Crick FHC (1953) A Structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171: 737–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]