Abstract

Objective

This study examined associations between profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood from parents and two dimensions of mental health in adulthood (negative affect and psychological well-being). Profiles were distinguished by the types of violence retrospectively self-reported (only physical, only psychological, or both psychological and physical violence), as well as by the frequency at which each type of violence reportedly occurred (never, rarely, or frequently).

Method

Multivariate regression models were estimated using data from the National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). An adapted version of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS) was used to collect respondents' reports of physical and psychological violence in childhood from each parent. Respondents also reported on current experiences of negative affect and psychological well-being.

Results

Regarding violence from mothers, reports of frequent psychological violence—even when coupled with never or rarely having experienced physical violence—were associated with more negative affect and less psychological well-being in adulthood. Nearly all profiles of violence in childhood from fathers—with the exception of reports of rare physical violence only—were associated with poorer adult mental health.

Conclusions

Results provide evidence that frequent experiences of psychological violence from parents—even in the absence of physical violence and regardless of whether such violence is from mothers or fathers—can place individuals' long-term mental health at risk. Moreover, frequent physical violence from fathers—even in the absence of psychological violence—also serves as a risk factor for poorer adult mental health.

Practice implications

Findings provide additional empirical support for the importance of prevention and intervention efforts directed toward children who experience physical and psychological violence from parents—even among adults who reportedly experienced only one type of violence and especially among adults who reportedly experienced psychological violence from either mothers or fathers at high levels of frequency.

Introduction

Recognizing that children who experience one type of violence are likely to experience other types of violence as well, scholars have noted an important gap in the literature on the long-term psychological consequences of childhood abuse (e.g., Higgins & McCabe, 2000; Kessler, Davis, & Kendler, 1997): Many studies have focused on single types of violence without accounting for individuals potentially having experienced other types of violence as well. Recent empirical work increasingly has addressed this gap, in part, by examining associations between the number of types of maltreatment that individuals report having experienced in childhood and adult mental health (e.g., Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O'Farrill-Swails, 2005; Clemmons, DiLillo, Martinez, DeGue, & Jeffcott, 2003; Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007; Higgins & McCabe, 2000). This approach, however, does not allow for examining whether specific types of violence—experienced alone or in combination with other particular types of violence—are differentially associated with poorer adult mental health. Also, although some studies have considered the independent and cumulative effects of physical and sexual abuse specifically (e.g., Arnow, Hart, Hayward, Dea, & Taylor, 2000; Diaz, Simantov, & Rickert, 2002; Sachs-Ericsson, Verona, Joiner, & Preacher, 2006), few studies have examined psychological violence as a potentially distinct or co-occurring type of violence (for exceptions, see Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards, et al., 2004; Kessler, David & Kendler, 1997; Schnieder, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007). Furthermore, much of the previous work that has considered linkages between multiple types of violence in childhood and adult mental health has used data from college students (e.g., Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007) or samples of women only (e.g., Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison, 1996; Schneider, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007). Expanded population work in this area is necessary to examine the mental health consequences of various, yet specific, types of childhood family violence within a broader population of adults.

This study aimed to address these gaps by using data from the National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS). We compared levels of mental health among adults reporting distinct profiles of physical and/or psychological violence in childhood from mothers and fathers. Profiles were distinguished by the types of violence reported (only physical, only psychological, or both physical and psychological), as well as by the frequency level at which each type of violence reportedly occurred (never, rarely, or frequently). We also examined whether associations between profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood and adult mental health differed for men and women.

Physical and psychological violence as distinct, yet related, types of violence

Although psychological violence is recognized as an important type of violence in its own right (e.g., National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect Clearinghouse, 2003), controversy regarding how to distinguish psychological violence from other types of violence remains (see Barnett, Perrin, & Miller-Perrin, 2005, for a discussion). Recognizing variation in approaches to defining psychological violence, McGee and Wolfe (1991) suggested that physical and psychological violence can be distinguished from each other along two dimensions: first, by whether or not the act of violence itself is physical or nonphysical/psychological, and second, by whether or not the consequences of the act are physical and/or nonphysical/psychological. This conceptualization recognizes that acts that are purely physical can have psychological consequences and that violence, overall, includes acts that are nonphysical/psychological. Recognition of physical and psychological violence as related-yet-distinct phenomena suggests the importance of examining the long-term psychological consequences of physical and nonphysical/psychological acts both in conjunction and independently from each other.

Research on the long-term effects of psychological violence—alone or in combination with physical violence—has lagged behind research on the long-term effects of other types of violence (Yates & Wekerle, 2009). Nevertheless, several studies have used population data to examine the long-term mental health consequences of physical and psychological violence in childhood (Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards, et al., 2004; Kessler, David & Kendler, 1997; Schnieder, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007). These studies provide evidence for physical and psychological violence in childhood as independent risk factors for poorer adult mental health. This study aimed to expand population work on linkages between physical and psychological violence in childhood and adult mental health in three ways: (1) by considering the frequency level at which physical and/or psychological violence reportedly occurred, (2) by testing for gender differences in associations, and (3) by examining two related, yet distinct, dimensions of mental health.

Frequency of violence in childhood and adult mental health

Scholars have posited that long-lasting experiences of violence can more profoundly damage a child's healthy development by creating cumulative problems at various developmental stages (Manly, Cicchetti, & Toth, 1994). Also, infrequent episodes of violence are more likely to result from transient family challenges, whereas chronic violence is more likely to result from and contribute to more enduring problematic patterns in family functioning that can undermine optimal child development (Cicchetti & Rizley, 1981).

Despite this theorizing on frequency as an important dimension for specifying experiences of violence in childhood, population-based studies on the long-term mental health effects of childhood family violence largely have categorized respondents into dichotomous groups indicating whether or not respondents report histories of childhood family violence, thereby not accounting for potential gradations in the frequency at which childhood violence reportedly occurred. For example, some scholars have coded respondents as having active histories of childhood family violence only if they reported violence having occurred at relatively high levels of frequency (e.g., Edwards, Holden, Felitti & Anda, 2003; Irving & Ferraro, 2006), thereby not addressing whether linkages of risk are also present at lower levels of frequency as well. This gap in previous research suggests the importance for population-based studies on the long-term mental health effects of children's experiences of violence to account for differential frequency levels of various types of violence that respondents reportedly experienced in childhood.

Gender differences in associations between childhood family violence and adult mental health

Theorists have posited several processes through which women might be more vulnerable to the negative psychological effects of interpersonal violence than men, such as women's more intense feelings of self-blame for being the target of violence and women's greater likelihood of responding to negative moods through rumination (Cutler & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Despite this theorizing, few studies have explicitly tested gender differences in associations, in large part because of limited samples that do not include data from both men and women (see Higgins & McCabe, 2000, for a review). Nevertheless, while results from some studies that have drawn on data from mixed-gender samples indicate that the associations between childhood family violence and adult mental health are stronger for women than for men (e.g., MacMillan, Fleming, Streiner, Lin, Boyle, et al., 2001), results from other studies have failed to find gender differences (e.g., Brems, Johnson, Neal, & Freemon, 2004). Inconsistencies in these findings suggest the importance of additional research on gender differences in linkages between childhood family violence and adult mental health.

A multi-dimensional approach to mental health

Much of the extant research on the long-term mental health effects of childhood family violence has focused on negative states of emotional well-being in adulthood, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress (see Springer, Sheridan, Kuo, & Carnes, 2003, for a review). Recent conceptualizations of mental health, however, suggest that mental ill-being is not synonymous with mental well-being (Keyes, 2002). Furthermore, approaches to mental health as a multi-dimensional construct also suggest that optimal mental health goes beyond maximum experiences of pleasure and minimal levels of pain; psychological well-being also involves positive psychosocial functioning and full engagement with life (Ryan & Deci, 2001), which may or may not be accompanied by particular emotional states.

Guided by a multi-dimensional approach to mental health, this study examined linkages between diverse profiles of childhood family violence and two theoretically derived and empirically validated aspects of adult mental health, including negative affect and psychological well-being (Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002). Negative affect involves experiences of negative moods and emotions (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) and has been importantly linked to depression and poorer health in adulthood (Charles & Almeida, 2006; Payton, 2009). Psychological well-being indicates positive functioning and engagement with life, such as feelings of purpose in life and perceptions of positive relationships with others (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), and has been increasingly understood as a distinct predictor of adult health outcomes (for a discussion, see Ryff, Singer, & Love, 2004).

Summary and research questions

In brief, based on the extant literature, this study aimed to extend understanding of linkages between experiences of physical and psychological violence in childhood and adult by using US population data to (1) differentiate among diverse histories of childhood family violence from parents by examining physical and psychological violence as potentially independent or co-occurring types of violence, (2) differentiate among histories of violence by considering the frequency level at which each type of violence (i.e., physical and psychological) reportedly occurred, (3) examine gender differences in associations between diverse experiences of physical and psychological violence in childhood and adult mental health, and (4) examine the psychological consequences of childhood family violence in terms of two theoretically-informed and empirically validated dimensions of mental health--negative affect and psychological well-being. Overall, we addressed the following research questions: Which patterns of physical and/or psychological violence from mothers and fathers during childhood are associated with poorer mental health in adulthood? Do these patterns of association vary by gender?

Method

Data and sample

This study conducted secondary analyses of publically available data from the National Survey of Midlife in the US (MIDUS). The MIDUS national probability sample included English-speaking, noninstitutionalized U.S. adults who were between the ages of 25 and 74 in 1995. The sample was obtained through random digit dialing; once a household was recruited into the study, a participant from the household was randomly selected, with older adults and men oversampled to ensure an adequate distribution on the cross-classification of age and gender. This study primarily used data from respondents in the first wave of data collection in 1995 when respondents were asked to report on their experiences of violence in childhood; the study also used data from a follow-up survey conducted in 2005 that included a question about history of sexual assault in childhood (see below) that was not included in the 1995 survey. The telephone interview lasted, on average, 30 minutes and largely addressed respondents' demographic information and medical histories. The lengthier mailback questionnaire focused also on respondents' health, in addition to psychological factors and social relationships.

The response rate for the 1995 MIDUS telephone interview was 70%. The response rate for the mailback questionnaire was 86.8% of telephone respondents, yielding an overall response rate of 60.8% for the sample that completed both the telephone interview and mailback questionnaire in 1995. This study used data only from the respondents who had completed both the telephone interview and mailback questionnaire (n = 3,024). Furthermore, we eliminated from the analytic sample those respondents who reported that violence from a particular parent did not apply to them (see the description of the measure of profiles of violence below), yielding a total analytic sample of 2,939 respondents within models regarding profiles of violence from mothers and an analytic sample of 2,831 respondent within models regarding profiles of violence from fathers.

Sampling weights correcting for selection probabilities and nonresponse were created to allow the sample to match the composition of the US population on age, gender, race, and education. In our models, we controlled for the main factors influencing primary sources of bias in the sample due to sample selection and nonresponse: age, gender, race, and education. We also examined results using both weighted data and unweighted data. Because the results from both weighted and unweighted data were similar, we report unweighted estimates here, which have more reliable standard errors (Winship & Radbill, 1994). (For a detailed technical report regarding field procedures, response rates, and weighting, see http://www.midus.wisc.edu.)

Measures

Negative affect

A six-item scale new to the MIDUS was used to measure negative affect (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). In the mailback questionnaire, respondents were asked how much of the time during the past 30 days they felt: (a) so sad nothing could cheer them up; (b) nervous; (c) restless or fidgety; (d) hopeless; (e) that everything was an effort; and (f) worthless. Respondents reported their experiences with each of these symptoms using a 5-point scale (1 = all of the time; 5 = none of the time). Scores on items were reverse coded and averaged such that higher scores indicated more negative affect. Cronbach's alpha for this index was .87. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for this and all other analytic variables.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for All Analytic Variables.

| Variable | Mean/Percentagea | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Variables | ||

| Female | 52% | |

| Age | 47.13 (13.07) |

25 – 74 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 83% | |

| Black | 7% | |

| Latino | 5% | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 5% | |

| Respondent Educationb | ||

| < 12 years | 9% | |

| 12 years | 29% | |

| 13 – 15 years | 31% | |

| 16+ years | 30% | |

| Parents' Educationb | ||

| < 12 years | 22% | |

| 12 years | 31% | |

| > 12 years | 31% | |

| Missing data | 17% | |

| Receipt of Welfare in Childhood | 6% | |

| Biological Parents Together in Childhood | 76% | |

| Household Income (in $10,000 units) | 5.43 (4.77) |

0 – 30 |

| Functional Health | 2.58 (2.89) |

0 – 9 |

| Marital Statusb | ||

| Married | 64% | |

| Never Married | 11% | |

| Widowed | 18% | |

| Divorced/Separated | 6% | |

| Employed | 72% | |

| History of Sexual Assaultb,c | ||

| First incident before the age of 18 | 4% | |

| First incident after the age of 18 | 2% | |

| No reported history | 34% | |

| Missing data | 60% | |

| Profiles of Psychological and Physical Violence from Mothers | ||

| Neither Physical nor Psychological | 37% | |

| One Type of Violence Only | ||

| Rare Physical Only | 11% | |

| Rare Psychological Only | 9% | |

| Frequent Physical Only | 2% | |

| Frequent Psychological Only | 3% | |

| Both Types of Violence | ||

| Rare Physical and Rare Psychological | 15% | |

| Rare Physical and Frequent Psychological | 6% | |

| Frequent Physical and Rare Psychological | 3% | |

| Frequent Physical and Frequent Psychological | 14% | |

| Profiles of Psychological and Physical Violence from Fathersb | ||

| Neither Physical nor Psychological | 35% | |

| One Type of Violence Only | ||

| Rare Physical Only | 8% | |

| Rare Psychological Only | 11% | |

| Frequent Physical Only | 4% | |

| Frequent Psychological Only | 1% | |

| Both Types of Violence | ||

| Rare Physical and Rare Psychological | 15% | |

| Rare Physical and Frequent Psychological | 8% | |

| Frequent Physical and Rare Psychological | 2% | |

| Frequent Physical and Frequent Psychological | 16% | |

| Mental Health | ||

| Negative Affect | 1.56 (0.63) |

1 – 5 |

| Psychological Well-Being | 5.52 (0.79) |

1 – 7 |

Note: Data are from the 1995-2005 National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS).

Percentages are reported for categorical variables, and means are reported for continuous variables with standard deviations reported in parentheses below.

Percentages do not sum to 100 because of rounding error.

This measure was only included in the 10-year follow-up of the survey in 2005.

Psychological well-being

An 18-item scale was used to measure psychological well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). This scale was developed from Ryff's (1989) integration of developmental, clinical, and social psychological theories on optimal adult functioning. In the mailback questionnaire, respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) with statements indicating psychological well-being within six domains, including feelings of self-acceptance (e.g., “I like most parts of my personality”), environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”), personal growth (e.g., “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”), purpose in life (e.g., “Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them”), autonomy (e.g., “I judge myself by what I think is important, not by the values of what others think is important.”), and positive relations with others (e.g., “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others.”). Cronbach's alpha for this index was .81.

Profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood

In the 1995 mailback questionnaire, respondents were presented with a series of items from a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1979). The CTS—which includes multiple subscales to measure different types of violence—is among the most commonly used measuring tools in the field of family violence (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Respondents were introduced to the series of items on childhood family violence as “three lists of things that happen to some children.” Two lists referred to acts of physical violence, with one including “pushed, grabbed, or shoved you; slapped you; threw something at you” and the other including “kicked, bit, or hit you with a fist; hit or tried to hit you with something; beat you up; choked you; burned or scalded you.” An additional list referred to acts of psychological violence, including “insulted you or swore at you; sulked or refused to talk to you; stomped out of the room; did or said something to spite you; threatened to hit you; smashed or kicked something in anger.” Participants indicated the extent to which their “mother, or the woman who raised them,” and their “father, or the man who raised them” engaged in any of the acts on each list by selecting among five response options—never, rarely, sometimes, often, and does not apply.

The two lists of physical violence included in the mailback questionnaire were originally intended to distinguish between acts of moderate and severe physical violence. Nevertheless, the authors of the CTS since have revised the instrument given concerns over the original items' discriminant validity (see Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998, for a discussion). Given these concerns, respondents' higher of the two frequency scores with respect to each list of physical violence was used as an indicator of the overall reported frequency of physical violence from a particular parent.

Preliminary descriptive analyses indicated that very few respondents reported never or rare experiences of one type of violence and often experiences of the other type from a particular parent. To ensure adequate cell sizes within multivariate models (see “data analytic sequence” below), while still maintaining distinctions among respondents who reported no violence versus occasional violence, as well as occasional violence versus frequent violence, we combined reports of “sometimes” and “often” were into a single category, which is hereafter referred to as frequent violence.

To code respondents into qualitatively distinct profiles of physical and psychological violence from mothers and fathers in childhood, we first identified respondents who reported having experienced neither physical nor psychological violence in childhood from a particular parent (i.e., mothers or fathers). The remaining respondents were coded into one of eight qualitatively distinct profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood with respect to each parent. Four of these profiles involved only one type of violence at varying levels of frequency, including: (1) rare psychological violence only, (2) rare physical violence only, (3) frequent psychological violence only, and (4) frequent physical violence only. The four other profiles involved both physical and psychological violence at varying levels of frequency, including: (1) rare physical violence and rare psychological violence, (2) rare physical violence and frequent psychological violence, (3) rare psychological violence and frequent physical violence, and (4) frequent physical violence and frequent psychological violence.

Sociodemographic and other control variables

To control for gender differences in negative affect and psychological well-being, as well as to test whether the main associations of interest varied for men and women, a dichotomous variable was created for gender, with women coded as 1 and men coded as 0. Additionally, given findings from previous studies indicating that a variety of other factors are associated with particular types of violence against children, as well as adult mental health, this study included measures of several additional variables as covariates in all models. First, previous studies have found that other childhood family characteristics—including childhood family structure, poverty, parental education, and race/ethnicity—are associated with one's likelihood of being the target of child abuse (Belsky, 1980) and adult mental health (Haas, 2008; Ross, Mirowsky, & Goldsteen, 1990; Ryff, Keyes, & Hughes, 2004). Accordingly, measures were created with respect to whether respondents reported living with both of their biological parents until the age of 16 (1 = yes, 0 = no), whether respondents reported a period of 6 months or more when their family was on welfare or Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) during their childhood or adolescence (1 = yes, 0 = no), and respondents' reports of their parents' highest level of educational attainment (including the categories of less than 12 years, 12 years, more than 12 years, and missing data on parents' education). Also, given that sexual abuse oftentimes co-occurs with other types of abuse (Higgins & McCabe, 2000), as well as a large body of research indicating linkages between childhood sexual abuse and poorer adult mental health (Jumper, 1995), a multi-categorical variable based on an item included only at the second wave of data collection in 2005 was used to assess respondents' history of sexual assault (with the categories of reported history of sexual assault before age 18, reported history of sexual assault after age 18, reported no history of sexual assault, or missing data on the item regarding sexual assault). To further control for co-occuring violence from both mothers and fathers, a variable that controlled for any psychological and/or physical violence from the other parent was also included in every model (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Previous studies also have found that reports of childhood family violence are also associated with sociodemographic factors in adulthood—such as socioeconomic status, employment status, marital status, and age (e.g., Hyman, 2000; Lee & Tolman, 2006; Rumstein-McKean & Hunsley, 2001)—and that these factors are likewise associated with adult mental health (e.g., Marmot, Fuhrer, Etnner, Marks, Bumpass, et al., 1998). Two variables were used to assess respondents' socioeconomic status in adulthood, including a multi-categorical variable for respondents' educational attainment (with the categories of less than 12 years, 12 years, 13-15 years, and 16 or more years) and a continuous measure of respondents' household income. Other variables measuring sociodemographic factors in adulthood included respondents' marital status (with the categories of currently married, separated/divorced, widowed, and never married at T1), employment status (1 = currently employed, 0 = not employed), and a continuous measure of age.

Data analytic sequence

The ordinary least squares method (OLS) was used to estimate a series of multiple regression models. All models included the control variables, and all outcomes were standardized at their means before estimating multivariate models. To examine linkages between profiles of violence from mothers in childhood and adult negative affect, we regressed negative affect on the multi-categorical variable indicating profiles of physical and psychological violence from mothers. This multi-categorical variable was entered into the OLS model as a series of dummy variables, with the reference group comprising respondents who reported neither psychological nor physical violence in childhood from mothers. Regression coefficients in this model, therefore, indicate the average differences in negative affect between (a) adults reporting each of the eight profiles of violence in childhood from mothers and (b) adults reporting neither psychological nor physical violence from mothers. We then estimated an additional model that included gender interaction terms indicating the product between each dummy variable indicating a different profile of violence from mothers and gender (e.g., Female X Rare psychological only). We repeated this same analytic sequence to examine linkages between violence from mothers and psychological well-being, as well as violence from fathers and adult negative affect and psychological well-being.

Results

Profiles of childhood family violence from mothers and fathers and adult negative affect

Table 2, Model 1a, displays estimates from models that regressed adult negative affect on the block of dichotomous variables indicating each of the profiles of physical and psychological violence from mothers. In this model, respondents who reported neither physical nor psychological violence from mothers served as the reference group. Regarding the profiles of violence that included one type of violence only, both profiles involving psychological violence without any reported physical violence were associated with greater negative affect (rare psychological violence only, b = .17, p ≤ .01; frequent psychological violence only, b = .33, p ≤ .01). By contrast, profiles involving physical violence from mothers without any reported psychological violence were not associated with greater negative affect (rare physical violence only, b = -.02, n.s.; frequent physical violence only, b= -.20, n.s).

Table 2. Estimated Regression Coefficients for the Associations between Profiles of Violence in Childhood from Mothers and Fathers and Negative Affect in Adulthooda.

| Violence from Mothers | Violence from Fathers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | |

| Female | .04 (.04) |

.04 (.06) |

.09* (.04) |

.08 (.06) |

| Reference Category of Violence | ||||

| Neither Physical nor Psychological | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| One Type of Violence Only | ||||

| Rare Physical Only | -.02 (.06) |

.02 (.08) |

-.14* (.07) |

-.14 (.10) |

| Rare Psychological Only | .17** (.06) |

.16 (.09) |

.13* (.06) |

.10 (.09) |

| Frequent Physical Only | -.20 (.13) |

-.19 (.17) |

.23** (.09) |

.41** (.15) |

| Frequent Psychological Only | .33** (.11) |

.40* (.18) |

.12 (.17) |

.05 (.21) |

| Both Physical and Psychological Violence | ||||

| Rare Physical and Rare Psychological | .16** (.05) |

.20 (.07) |

.11* (.06) |

.10 (.08) |

| Rare Physical and Frequent Psychological | .43*** (.07) |

.40*** (.11) |

.29*** (.07) |

.21* (.10) |

| Frequent Physical and Rare Psychological | .26** (.10) |

.39** (.14) |

.19 (.12) |

.20 (.15) |

| Frequent Psychological and Frequent Physical | .45*** (.06) |

.33*** (.08) |

.38*** (.06) |

.37*** (.08) |

| Gender Interactions | ||||

| Female X Rare Physical Only | -.07 (.12) |

-.03 (.14) |

||

| Female X Rare Psychological Only | .03 (.12) |

.05 (.12) |

||

| Female X Frequent Psychological Only | -.10 (.22) |

.20 (.37) |

||

| Female X Frequent Physical Only | -.02 (.26) |

-.31 (.19) |

||

| Female X Rare Physical and Rare Psych | -.08 (.11) |

.02 (.11) |

||

| Female X Rare Physical and Freq Psych | .06 (.15) |

.16 (.12) |

||

| Female X Freq Phys and Rare Psych | -.30 (.20) |

- .05 (.24) |

||

| Female X Freq Physical and Freq Psych | .21 (.11) |

.02 (.11) |

||

| Constant | .25* (.12) |

.26* (.12) |

.27* (.12) |

.28* (.12) |

| R2 | .21 | .21 | .21 | .21 |

| Valid n | 2789 | 2789 | 2681 | 2681 |

Notes: Data are from the National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. 1995-2005 (MIDUS). All models also included as covariates measures of respondents reports of their parents' education, childhood family structure, receipt of welfare in childhood, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, household income, marital status, age, report of ever experiencing sexual assault in childhood, and report of any psychological and/or physical violence from the other parent in childhood.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed).

Scores were standardized at their means.

All profiles of violence from mothers that involved both physical and psychological violence were associated with greater negative affect. These profiles included reports of rare physical and rare psychological (b = .16, p ≤ .01), rare physical and frequent psychological (b = .43, p ≤ .001), frequent physical and rare psychological (b = .26, p ≤ .01), and frequent physical and frequent psychological (b = .45, p ≤ .001).

Table 2, Model 1b, displays estimates from models that regressed adult negative affect on the block of dichotomous variables indicating each of the profiles of childhood violence from fathers. In this model, respondents who reported neither physical nor psychological violence from fathers served as the reference group. Regarding the profiles of violence involving one type of violence only, two profiles were associated with greater negative affect--rare psychological violence only (b = .13, p ≤ .05) and frequent physical violence only (b = .23, p ≤ .01). Reports of frequent psychological violence only were not associated with negative affect (b = .12, n.s.), and reports of rare physical violence only were associated with less negative affect (b = -.14, p ≤ .05).

Nearly all profiles of violence from fathers that involved both physical and psychological violence were associated with greater negative affect, including rare physical and rare psychological violence (b = .11, p ≤ .05), rare physical and frequent psychological violence (b = .29, p ≤ .001), and frequent physical and frequent psychological violence (b = .38, p ≤ .001). Reports of frequent physical and rare psychological violence from fathers were not associated with greater negative affect (b = .19, n.s.).

In short, these results indicated that experiences of both psychological and physical violence from mothers and/or fathers—regardless of the frequency level of either type of violence—were associated with greater negative affect in adulthood. Reports of psychological violence from mothers—regardless of frequency level—were also associated with greater negative affect. Results regarding single types of violence from fathers and negative affect were mixed.

Profiles of childhood family violence from mothers and fathers and adult psychological well-being

Table 3, Model 1a, displays estimates from models in which adult psychological well-being was regressed on the block of dichotomous variables indicating each of the profiles of childhood violence from mothers. In this model, respondents who reported neither physical nor psychological violence from mothers served as the reference group. Regarding the profiles of violence involving one type of violence only, the profile involving frequent psychological violence without any reported physical violence was associated with poorer psychological well-being (b = -.25, p ≤ .05). No other profile involving only one type of violence from mothers was associated with poorer psychological well-being (rare physical violence only, b = .01, n.s.; rare psychological violence only, b = -.06, n.s.; frequent physical only, b = -.09, n.s.).

Table 3. Estimated Regression Coefficients for the Associations between Profiles of Violence in Childhood from Mothers and Fathers and Psychological Well-Being in Adulthooda.

| Violence from Mothers | Violence from Fathers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | |

| Female | .06 (.04) |

.02 (.06) |

.03 (.04) |

.06 (.06) |

| Reference Category of Violence | ||||

| Neither Psychological nor Physical | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| One Type of Violence Only | ||||

| Rare Physical Only | .01 (.06) |

-.05 (.09) |

.01 (.08) |

.02 (.11) |

| Rare Psychological Only | -.06 (.07) |

-.08 (.09) |

-.18** (.06) |

-.18 (.10) |

| Frequent Physical Only | -.09 (.14) |

.04 (.18) |

-.24* (.10) |

-.44** (.15) |

| Frequent Psychological Only | -.25* (.11) |

-.52** (.19) |

-.37* (.17) |

-.16 (.21) |

| Both Physical and Psychological Violence | ||||

| Rare Physical and Rare Psychological | -.05 (.06) |

-.08 (.08) |

-.13* (.06) |

-.10 (.08) |

| Rare Physical and Frequent Psychological | -.26*** (.08) |

-.28* (.12) |

-.28*** (.07) |

-.11 (.10) |

| Frequent Physical and Rare Psychological | -.12 (.11) |

-.22 (.14) |

-.30** (.12) |

-.17*** (.16) |

| Frequent Physical and Frequent Psychological | -.35*** (.06) |

-.33*** (.09) |

-.31*** (.06) |

-.31*** (.08) |

| Gender Interactions | ||||

| Female X Rare Physical Only | .12 (.13) |

.01 (.15) |

||

| Female X Rare Psychological Only | .05 (.13) |

.01 (.13) |

||

| Female X Frequent Physical Only | -.29 (.28) |

.35 (.20) |

||

| Female X Frequent Psychological Only | .42 (.12) |

-.65 (.37) |

||

| Female X Rare Physical and Rare Psych | .08 (.11) |

-.04 (.12) |

||

| Female X Rare Physical and Freq Psych | .04 (.16) |

-.36** (.15) |

||

| Female X Freq Physical and Rare Psych | .22 (.21) |

- .31 (.25) |

||

| Female X Freq Physical and Freq Psych | -.03 (.11) |

.03 (.11) |

||

| Constant | -.00 (.12) |

.03 (.13) |

.02 (.13) |

-.00 (.13) |

| R2 | .16 | .17 | .16 | .16 |

| Valid n | 2675 | 2675 | 2570 | 2570 |

Notes: Data are from the National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. 1995-2005 (MIDUS). All models also included as covariates measures of respondents reports of their parents' education, childhood family structure, receipt of welfare in childhood, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, household income, marital status, age, report of ever experiencing sexual assault in childhood, and report of any psychological and/or physical violence from the other parent in childhood.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed).

Scores were standardized at their means.

Among the profiles of violence involving both physical and psychological violence, both profiles involving frequent psychological violence were associated with poorer psychological well-being (rare physical and frequent psychological violence, b = -.26, p ≤ .001; frequent physical and frequent psychological violence, b = -.35, p ≤ .001). The other two profiles involving both physical and psychological violence were not associated with psychological well-being (rare physical and rare psychological, b = -.05, n.s.; frequent physical and rare psychological, b = -.12, n.s.).

Table 3, Model 1b, displays estimates from models that regressed adult psychological well-being on the block of dichotomous variables indicating each of the profiles of childhood violence from fathers. In this model, respondents who reported neither physical nor psychological violence from fathers served as the reference group. Nearly all profiles of violence involving only one type of violence were associated with poorer psychological well-being, including frequent psychological violence only (b = -.37, p ≤ .05), frequent physical violence only (b = -.24, p ≤ .05), and rare psychological violence only (b = -.18, p ≤ .01). Reports of rare physical violence without any reported psychological violence from fathers were not associated with psychological well-being (b = .01, n.s.).

All profiles of violence involving both physical and psychological violence from fathers were associated with poorer adult psychological well-being. These profiles included rare physical and rare psychological violence (b = -.13, p ≤ .05), rare physical and frequent psychological violence (b = -.28, p ≤ .001 [but note gender interaction below]), frequent physical and rare psychological violence (b = -.30, p ≤ .01), and frequent physical and frequent psychological violence (b = -.31, p ≤ .001).

In brief, results indicated that frequent psychological violence from mothers—regardless of whether or not such violence was reportedly accompanied by physical violence—was associated with poorer adult psychological well-being. Furthermore, reports of both psychological and physical violence from fathers—regardless of frequency levels—were associated with poorer psychological well-being, as were reports of frequent physical violence only, frequent psychological violence only, and even rare psychological violence only.

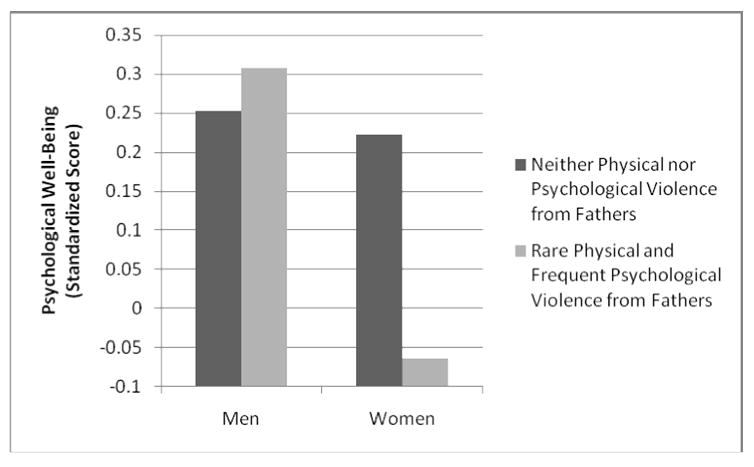

Gender differences in associations between childhood family violence from mothers and fathers and adult mental health

Models 2a and 2b in Tables 2 and 3 display models that included gender interaction terms, which indicate the product between each profile of physical and psychological violence from a particular parent by the dichotomous measure of gender. These models indicated only one statistically significant gender interaction term (see Table 2, Model 2b), specifically in the association between Female X Rare physical and frequent psychological violence from fathers and psychological well-being (b = -.36, p ≤ .01). Figure 1 displays predicted scores of psychological well-being for women and men who reported either (1) never having experienced physical or psychological violence from fathers in childhood, or (2) having experienced rare physical and frequent psychological violence from fathers. This figure suggests that whereas rare physical and frequent psychological violence from fathers was not associated with poorer psychological well-being among men, this profile of violence from fathers was associated with poorer psychological well-being among women. Overall, these results provide very limited support for gender differences in associations between profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood and adult mental health.

Figure 1.

Predicted scores of psychological well-being in adulthood for women and men who reported either (1) never having experienced physical or psychological violence from fathers, or (2) rare physical and frequent psychological violence from fathers

Discussion

This study aimed to further understanding of the long-term mental health consequences of individuals' experiences of family violence in childhood by examining patterns of associations between distinct profiles of physical and psychological violence in childhood from mothers and fathers and two aspects of adult mental health—negative affect and psychological well-being. Profiles were distinguished by the types of violence retrospectively self-reported (only physical, only psychological, or both psychological and physical violence), as well as by the frequency at which each type of violence reportedly occurred (never, rarely, or frequently).

Regarding linkages between profiles of violence and adult mental health in terms of negative affect, nearly all profiles involving both physical and psychological violence—regardless of whether such violence was from mothers or fathers—were associated with greater levels of adult negative affect. These results are congruent with those of previous studies, which have found that experiencing multiple types of maltreatment is a powerful risk factor for poorer mental health in adulthood (Clemmons, DiLillo, Martinze, DeGue, & Jeffcott, 2003; Higgins & McCabe, 2000; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O'Farrill-Swails, 2005).

Notably, there was some evidence, in addition, that profiles of violence involving only one type of violence were also associated with greater adult negative affect. Regarding violence from mothers, reports of psychological violence only were associated with greater negative affect—regardless of whether such violence was reported as having occurred rarely or frequently. Regarding violence from fathers, frequent psychological violence only was also associated with greater negative affect, as was frequent physical violence only. These results are congruent with those of other studies that have demonstrated that experiences of even one type of violence can pose long-term mental health risks (e.g., Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards, et al., 2004; Kessler, David, & Kendler, 1997; Schnieder, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007; Spertus, Yehuda, Wong, Halligan, & Seremetis, 2003).

Unexpectedly, results indicated that one profile of violence in childhood from parents was associated with better adult mental health in terms of negative affect. Specifically, respondents who reported having rarely experienced physical violence from fathers, but never having experienced psychological violence from fathers, demonstrated lower levels of adult negative affect. Perhaps occasional episodes of physical violence from fathers indicate other father-respondent childhood interactions with potential developmental advantages, such as greater quantity or quality of father-child play (Paquette, 2004) or fathers' use of reasoned physical discipline (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). Additional research that replicates this finding and that explores fathers' occasional use of physical violence—without any psychological violence—is necessary for better understanding this result.

Regarding linkages between profiles of violence and adult mental health in terms of psychological well-being, results indicated that nearly all profiles of physical and psychological violence from fathers were associated with poorer psychological well-being. Evidence for linkages with respect to violence from mothers emerged only with respect to profiles involving frequent experiences of psychological violence. Furthermore, results provided limited support for differences in associations between profiles of violence and adult mental health for men and women. Qualitative work that explores potentially nuanced meanings around mothers' and fathers' use of physical violence would enhance understanding of how context contributes to the long-term psychological effects of family violence. Also, qualitative work on how gender contributes to meaning-making around experiences of childhood family violence, would help elucidate the potentially nuanced processes through which childhood family violence jeopardizes men and women's adult mental health perhaps to similar degrees, but through different processes.

Despite this study's conceptual and methodological strengths, including its relatively in-depth analysis of various profiles of childhood family violence while also using data from a U.S. national survey, several of its features limit the full extent to which conclusions can be made regarding the implications of various profiles of violence from parents in childhood for adult mental health. First, despite this study's inclusion of many statistical controls, there are other factors that this study did not account for—such as genetic factors, other forms of child maltreatment, and other types of childhood family adversities—which, if taken into account, might yield a more complex causal story. Also, despite this study's inclusion of a statistical control for lifetime incidence of sexual assault, missing data on this measure make it possible that histories of sexual abuse are still statistically conflated with profiles of physical and psychological violence. Causal inferences are also somewhat tenuous given the retrospective nature of this study's measure of childhood family violence. Linkages might, in part, reflect processes of reverse causality in which individuals' poorer mental health causes them to more readily recall negative interpersonal interactions from childhood. Similarly, adults with poorer mental health might have had poorer mental health in childhood before experiencing violence, thereby placing them at greater risk for experiencing violence in childhood from parents.

Other limitations of this study result from remaining variability in experiences of violence even within specific profiles of violence. For example, due to limitations in the measurement index, this study was unable to distinguish among severity levels of psychological or physical violence in terms of the acts' likelihood of having caused serious injury. Also, this study's measure of childhood family violence did not attempt to assess why childhood violence reportedly occurred. Differences in contexts surrounding the use of violence (e.g., reasoned discipline versus acts of unprovoked rage) are likely to influence linkages between childhood family violence and adult mental health. Furthermore, this study focused on subgroup differences in linkages by gender only. Other potentially important subgroup differences include subgroup differences by age, past and present supportive interactions in parent-child relationships, and the developmental periods over which violence from parents occurred.

Finally, it is possible that associations between some profiles of physical and psychological violence did not achieve statistical significance because of the relatively small number of respondents in some profile groups. Associations for some other profiles of violence might have reached statistical significance if such profiles had included even larger cell sizes of respondents, allowing for more statistical power to detect smaller—but still notable—associations. Also, patterns of survey non-participation and non-response raise concerns about biased estimates of population parameters (Acock, 2005).

Despite these limitations, this study contributes additional evidence for the long-term mental health consequences of children's experiences of violence from parents. Results suggest that adverse mental health consequences can result from experiencing only one type of violence—psychological or physical—as well as from either psychological or physical violence at relatively low levels of frequency. It is important for additional research in this area to explicitly consider variations among individuals' experiences of violence in childhood. Developing a more refined understanding of who is at greatest risk for poorer adult outcomes due to family violence in childhood can help to develop more targeted practice and policy measures to foster optimal mental health for individuals with problematic histories of family violence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants AG206983 and AG20166 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–28. [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O'Farrill-Swails L. Single versus multi-type maltreatment.: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2005;11:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA, Hart S, Hayward C, Dea R, Taylor CB. Severity of child maltreatment, pain complaints and medical utilization among women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2000;34:413–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(00)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett O, Miller-Perrin C, Perrin RD. Family violence across the lifespan: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. American Psychologist. 1980;35:320–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems C, Johnson ME, Neal D, Freemon M. Childhood abuse history and substance use among men and women receiving detoxification services. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:799–821. doi: 10.1081/ada-200037546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Whitfield CL. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rizley R. Developmental perspectives on the etiology, intergenerational transmission, and sequelae of child maltreatment. In: Rizely R, Cicchetti D, editors. Developmental perspective on child maltreatment: New Directions for child development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1981. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, DiLillo D, Martinez IG, DeGue S, Jeffcott M. Co-occurring forms of child maltreatment and adult adjustment reported by latina college students. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:751–767. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SF, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Accounting for sex differences in depression through female victimization: Childhood sexual abuse. Sex Roles. 1991;24:425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Simontov E, Rickert VI. Effect of abuse on health. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:811–817. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the adverse childhood experiences study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving S, Ferraro K. Reports of abusive experiences during childhood and adult health ratings. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:458–485. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. Trajectories of functional health: The ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman B. The economic consequences of child sexual abuse for adult lesbian women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;6:547–578. [Google Scholar]

- Jumper SA. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to adult psychological adjustment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:715–728. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. Complete mental health: An agenda for the 21st century. In: Keyes CLM, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Tolman RM. Childhood sexual abuse and adult work outcomes. Social Work Research. 2006;30:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, Duku EK, Walsh CA, Wong MY, Beardslee WR. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Fuhrer R, Ettner SL, Marks NF, Bumpass LL, Ryff CD. Contribution of psychosocial factors to socioeconomic differences in health. The Millbank Quarterly. 1998;76:403–448. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Wolfe DA. Psychological maltreatment: Toward an operational definition. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: A community study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect Clearinghouse. Types of child abuse and neglect. [Electronic Version] 2003 Retrieved 31, 5, 2009, from http://www.childwelfare.gov/can/types/

- Paquette D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development. 2004;47:193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Payton AR. Mental health, mental illness, and psychological distress: Sam continuum or distinct phenomena. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:213–227. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Goldsteen K. The impact of the family on health: The decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1059–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Rumstein-McKean O, Hunsley J. Interpersonal and family functioning of female survivors of childhood sexual buse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:471–490. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;59:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM, Hughes DL. Psychological well-being in MIDUS: Profiles of ethnic/racial diversity and life-course uniformity. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 398–424. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH, Love GD. Positive health: Connecting well-being with biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2004;359:1383–1394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Verona E, Joiner T, Preacher KJ. Parental verbal abuse and the mediating role of self-criticism in adult internalizing disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Baumrind N, Kimderling R. Exposure to child abuse and risk for mental health problems in women. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:620–631. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. The long-term health outcomes of childhood abuse: An overview and a call to action. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:864–870. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Wekerle C. The long-term consequences of childhood emotional maltreatment on development: (Mal)adaptation in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1994;23:230–257. [Google Scholar]