Abstract

Cholinergic anthelmintics (like levamisole) are important drugs but resistance with reduced responses by the parasite to these compounds is a concern. There is a need to study and understand mechanisms that affect the amplitude of the responses of parasites to these drugs. In this paper, we study interactions of levamisole and ryanodine receptors on contractions of Ascaris suum body muscle flaps. In our second paper, we extend these observations to examine electrophysiological interactions of levamisole, ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and AF2. We report that the maximum force of contraction, gmax, was dependent on the extracellular concentration of calcium but the levamisole EC50(0.8 μM) was not. The relationship between maximum force of contraction and extracellular calcium was described by the Michaelis-Menten equation with a Km of 1.8 mM. Ryanodine inhibited gmax without effect on EC50; ryanodine inhibited only 44% of the maximum contraction (Ki of 40 nM), revealing a ryanodine-insensitive component in the levamisole excitation-contraction pathway. Dantrolene had the same effect as ryanodine but was less potent. The neuropeptide AF2 (1 μM) decreased the levamisole EC50 to 0.2 μM without effect on gmax; 0.1 μM ryanodine and 100 μM dantrolene, inhibited the gmax of the AF2-potentiated levamisole response. High concentrations of caffeine, 30 mM, produced weak contraction of the body flap preparation. Caffeine behaved like ryanodine in that it inhibited the maximum force of contraction, gmax, without effects on the levamisole EC50. Thus, RyRs play a modulatory role in the levamisole-excitation contraction pathway by affecting the maximum force of contraction without an effect on levamisole EC50. The levamisole-excitation contraction coupling is graded and has at least two pathways: one sensitive to ryanodine and one not.

Keywords: Ascaris suum, levamisole, contraction, ryanodine, caffeine, AF2

1. Introduction

The cholinergic anthelmintics like levamisole are significant therapeutic agents used to treat nematode parasite infections of man and animals but resistance can limit their efficacy [1]. There is an urgent need to understand the mechanisms that affect the amplitude of the response to these drugs and that might be involved in the development of resistance. Levamisole is an ionotropic cholinergic agonist that selectively produces depolarization of nematode muscle and spastic contraction [2]. We have shown using current-clamp, voltage-clamp and patch-clamp, that electrophysiological responses to levamisole can be observed in body muscle cells of the nematodes Ascarissuum, Oesophagostomum dentatum and C. elegans [3 - 6]. These studies have identified and described the nematode nicotinic acetylcholine gated receptor channels (nAChRs) on nematode muscle that is selectively gated by levamisole. Following opening of the nAChRs by levamisole, a signaling cascade is initiated that leads to contraction of the muscle.

Nematode body muscle contains actin and myosin that form thick and thin filaments. The filaments are stacked at an angle rather than adjacently to the length of the muscle, so nematode muscle is classified as obliquely striated [7]. Our knowledge of details of the excitation-contraction coupling mechanism of obliquely striated muscle is limited; we do not know how similar the excitation-contraction coupling process is to vertebrate skeletal, cardiac muscle or smooth muscle. We know in A. suum and C. elegans, that there are voltage-activated calcium currents present in muscle [8] but contraction does not follow individual action potentials as in most skeletal or cardiac muscle. In C. elegans, ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are present in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which is formed from a network of membranous vesicles and sacs that surround the dense bodies where thin-filaments are attached [9]. The sarcoplasmic reticulum is located close to the plasma membrane [10; 11] from which calcium is released into the cytoplasm. C. elegans null mutants of the ryanodine receptor gene, unc-68, are still motile but they have reduced mobility, suggesting that RyRs are not essential for contraction in nematodes but that they modulate muscle contraction [11]. These C. elegans unc-68 null mutants are also less sensitive to the effects of levamisole suggesting that unc-68 could be involved in resistance to levamisole in parasitic nematodes.

There is still much to learn about the modes of action of the nicotinic anthelmintics and how opening of the nAChRs by the anthelmintic are coupled to muscle contraction in parasitic nematodes. For example, we do not know what the immediate source of the calcium required for levamisole induced contractions is. Although we expect RyRs to affect the levamisole contraction response, we do not know if, or how, the amplitude of muscle contraction is affected by the activity of the RyRs; and this information is anticipated to relate to levamisole resistance. In this paper, we use a muscle contraction assay in Ascaris suum to investigate, using pharmacological agents, the role of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in the response to levamisole in nematode muscle. In our second paper, we extend these observations to examine electrophysiological interactions of levamisole, ryanodine and AF2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Collection of worms

Adult A. suum were obtained weekly from the Tyson’s pork packing plant at Storm Lake, Iowa. Worms were maintained in Locke’s solution [Composition (mM): NaCl 155, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 1.5 and glucose 5] at a temperature of 32°C. The Locke’s solution was changed daily and the worms were used within 3 days of collection.

2.2 Ascaris suum muscle flap contraction assays

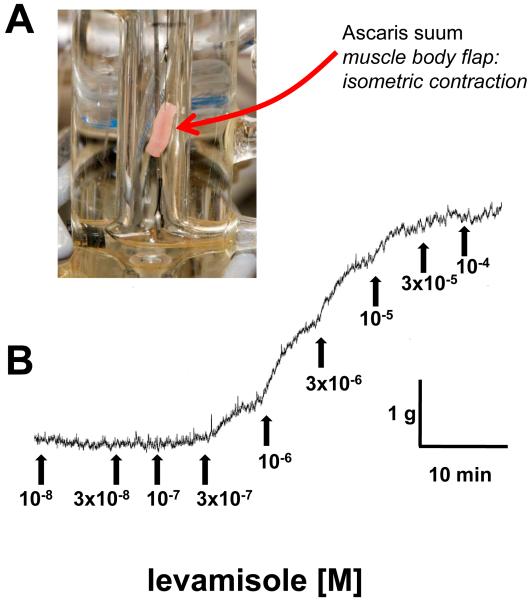

The A. suum were used for the contraction studies within 72 hours, since the ability to contract vigorously to cholinergic agonists declined after this period. Two 1-cm body-flap preparations, one dorsal and one ventral, were made from each A. suum female from the region anterior to the genital pore. The lateral line was removed from the edge of the flaps. Each flap was monitored isometrically by attaching a force transducer in an experimental bath, Fig. 1A, maintained at 37°C containing 10 ml APF Ringer (mM): NaCl, 23; Na-acetate, 110; KCl, 24; CaCl2, 6; MgCl2 5; glucose, 11; HEPES, 5; pH 7.6 with NaOH and bubbled with nitrogen. Eight baths were used simultaneously. After dissection, the preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min under an initial tension of 2.0 g. The ryanodine, dantrolene, caffeine and AF2, were added to the preparation 15 min before the application of the first concentration of levamisole. We ran two controls (no inhibitory drugs) and three replicate inhibitory concentrations during each experiment (8 preparations). The dorsal and ventral flaps were assigned randomly in the experiments to reduce any potential error associated with differences in receptor populations. Levamisole was added cumulatively with ~5 minute intervals between applications and the responses were steady changes in tension. Fig. 1B is a representative trace of a graded response to increasing levamisole concentrations. Results for individual flaps were rejected if the maximum change in tension, at the highest agonist concentration, did not exceed 0.5 g. The responses for each concentration were expressed as the gram force tension produced by each individual flap preparation. The mean maximum amplitude of contraction of our muscle strips varied on a weekly basis (each batch of worms was collected weekly). Control and test experiments on the effects of calcium or drugs were conducted on muscle strips prepared from the same batches of A. suum.

Fig. 1.

Ascaris suum body muscle flap preparation for contraction assay.

A: Flap preparation mounted between an isometric force transducer and fixed position. Maintained at 37°C in glass cylinder surrounded by a glass jacket containing heated water.

B: Representative control cumulative levamisole concentration and isometric contraction relationship.

2.3 Recording and Analysis of contraction

Changes in isometric muscle tension responses were monitored using a PowerLab System (AD Instruments Colorado Springs, CO) that consists of the PowerLab hardware unit and Chart for Windows software. The system allows for recording, displaying and analysis of experimental data. Sigmoid concentration-response curves for each individual flap preparation at each concentration of antagonist were fitted using Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to estimate the constants by non-linear regression for each group of preparations receiving the same treatment. In preparations where desensitization was evident (seen as a reduced response to a higher concentration of levamisole), the maximum response was used for fitting. The pEC50 was calculated as the negative logarithm of EC50. To illustrate the agonist concentration-response relationship at each concentration of antagonist, the lines of best fit were used for the figure displays.

2.4 Drugs

AF2 (H - Lys - His - Glu - Tyr - Leu - Arg - Phe - NH2) [Sigma-Genosys, The Woodlands, Tx, USA] 10 mM stock solutions were prepared in double distilled water every week and kept in Ependorf tubes at −20°C. AF2, stock solutions were thawed just before use to make up the solutions. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Mean ± S.E. contractions were determined. All the statistical analysis, including the curve fitting, was done using GraphPad 5.01, Prism software, San Diego, CA. Unpaired t-tests were employed to test the statistical significance of the difference between control and test contraction experiments; significance levels were set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Extracellular calcium is required for levamisole-induced contraction

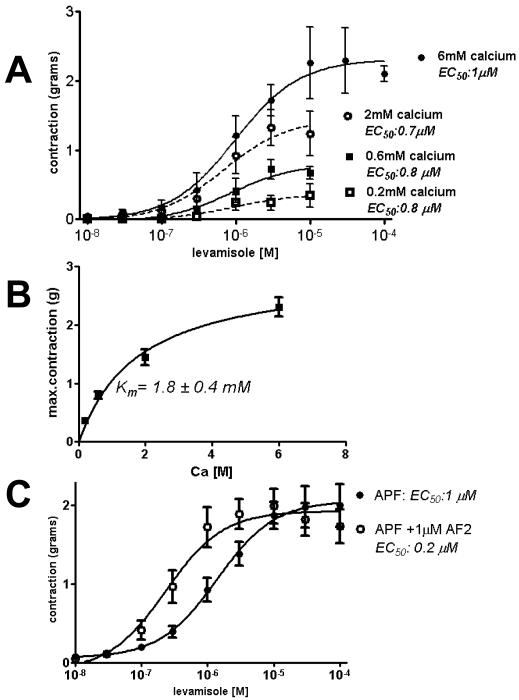

Fig. 2A shows that levamisole produces graded concentration-dependent muscle contractions and that the amplitude of the contractions is dependent on extracellular calcium. We described the concentration-response plots by fitting the equation:

| equation 1, |

where g, is the response in grams, [lev] is the levamisole molar concentration, EC50 is the concentration of levamisole producing 50% of the maximum response, gmax. The EC50 was 1 μM with 6 mM extracellular calcium. The levamisole EC50 value was not sensitive to extracellular calcium but the maximum amplitude, gmax, of contraction was; it decreased with a decrease in extracellular calcium. The relationship between extracellular calcium concentration and the maximum force of contraction, gpeak, was described by the Michaelis-Menten equation:

| equation 2, |

where gpeakmax is the maximum gpeak obtained in a high concentration of calcium, [Ca], and Km is the concentration of calcium producing 50% of gpeakmax. Fig. 2B shows the Michaelis-Menten fit: gpeakmax was 2.9 g and Km was 1.8 mM. It is clear that the maximum amplitude or force of the levamisole-induced contraction is dependent on the extracellular concentration of calcium but the levamisole EC50 is not. A. suum muscle is obliquely striated muscle [12; 13] and, as we have shown above, it requires extracellular calcium during the graded contractions, prior exposure to extracellular calcium is not sufficient.

Fig. 2.

Calcium sensitivity of levamisole concentration contraction plots.

A: Log cumulative levamisole concentration contraction plots and fitted line to estimate gmax and EC50. See Results for equation and estimates.

B: Plot of extracellular calcium concentration vs. maximum force of contraction, gpeak and fitted line to Michaelis-Menten equation to estimate gpeakmax and Km, see Results for equation and estimates. The force of the levamisole-induced contraction was dependent on the extracellular concentration of calcium but the levamisole EC50 was not.

C: Log cumulative levamisole concentration contraction plots in the presence and absence of 1 μM AF2. The control levamisole gmax was 2.0 ± 0.1 g (n = 10 preparations, DF = 87); in 1 μM AF2, the levamisole gmax was not significantly different, 1.9 ± 0.1 g (n = 10 preparations, DF = 87, p >0.05). The control levamisole EC50 was 1 μM (pEC50 was 5.86 ± 0.13, n = 10 preparations, DF = 87) and changed in 1 μM AF2, where the levamisole EC50 was 0.2 μM (pEC50, 6.63 ± 0.16, n = 10 preparations, DF = 87, p < 0.05). AF2 produced a 5-fold decrease in the levamisole EC50 without an effect on gmax.

3.2 Effects of AF2

We also looked at effects of the excitatory neuropeptide, AF2, a peptide that has been demonstrated to increase opening of voltage-activated calcium channels and may therefore stimulate release of calcium from RyRs [8; 14]. The neuropeptide AF2 increases the force of contraction produced by application of cholinergic agonists including levamisole. We tested the effect of 1 μM AF2 present all the time, on the levamisole-concentration contraction response, Fig 2C. The control levamisole gmax was 2.0 g; in 1 μM AF2, the levamisole gmax was unchanged at 1.9 g but there was a significant 5-fold decrease in the control levamisole EC50 from 1 μM to 0.2 μM. Thus, AF2 increased the sensitivity to levamisole by decreasing the EC50 but without change in gmax.

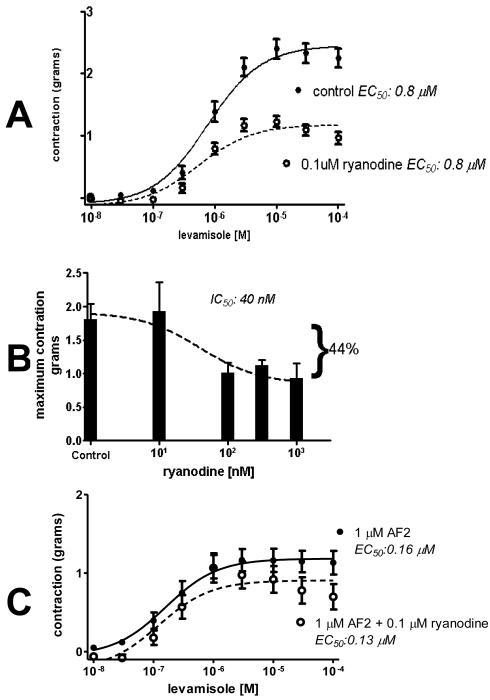

3.3 Effects of ryanodine on levamisole induced contractions

In order to investigate the role of the RyRs in A. suum, we next investigated effects of ryanodine. Ryanodine is an alkaloid from a South American plant Ryania speciosa that was originally used as an insecticide [15]. It has a high affinity for RyR channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The effect of ryanodine on C. elegans RyRs in membrane bilayers is to lock the RyR channels open in a subconductance state [16].

In our experiments, ryanodine, at a concentration of 10 nM or less, had little effect on levamisole-induced contractions, but at concentrations, ≥ 100 nM, ryanodine inhibited the maximum force of contraction without producing an effect on an effect on EC50. In addition, ryanodine, by itself, did not produce contraction. Fig. 3A shows the effect of 0.1 μM ryanodine on the levamisole contractions. The control levamisole gmax was 2.5 g; in 0.1 μM ryanodine, the levamisole gmax was reduced to 1.2 g. The control levamisole EC50 was 0.84 μM and essentially unchanged in 0.1 μM ryanodine, where the levamisole EC50 was 0.79 μM. Fig. 3B shows that high (1μM) concentrations of ryanodine reduced the maximum levamisole contraction by nearly one-half with an IC50 of 40 μM, but did not inhibit all contraction. The limited inhibitory effect of high concentrations of ryanodine suggests: 1) that RyRs increase the maximum force of levamisole contraction by increasing the rise of cytosolic calcium by calcium-induced-calcium release; and 2) that levamisole also activates a RyR independent calcium pathway.

Fig. 3.

Ryanodine sensitivity of levamisole contractions.

A: Plots of the inhibitory effect of 0.1 μM ryanodine on the cumulative-levamisole-concentration contraction response. The control levamisole gmax was 2.5 ± 0.1 g (n = 10 preparations, DF = 87); in 0.1 μM ryanodine, the levamisole gmax was significantly reduced to 1.2 ± 0.1g (n = 10 preparations, DF 87, p < 0.05). The control levamisole EC50 was 0.84 μM (pEC50 was 6.07 ± 0.02, n = 10 preparations, DF = 73) and not significantly changed in 0.1 μM ryanodine where the levamisole EC50 was 0.79 μM (pEC50 was 6.10 ± 0.03, n = 9 preparations, DF = 66 p > 0.05).

B: Plot of the inhibitory effect of ryanodine concentration on the maximum force of contraction gmax. The high concentrations of ryanodine reduced the maximum levamisole contraction by 44% with an IC50 of 40 μM, but did not inhibit all of the contraction. The maximum inhibitory effect of high concentrations of ryanodine suggests that RyRs modulates one but not all calcium pathways to reduce the maximum force of contraction. Because ryanodine did not inhibit all of the levamisole contractions, it suggests that levamisole also activates RyR independent calcium pathways that are able to produce contraction, see Fig. 6

C: Plots of the inhibitory effect of 0.1 μM ryanodine on 1 μM AF2 potentiated levamisole concentration contraction plots. 0.1 μM ryanodine significantly reduced gmax from 1.19 g ± 0.13 (AF2 control: n = 10 preparations, DF = 87) to 0.91 ± 0.07 g (n = 10 preparations, DF= 87 p< 0.05). Ryanodine had little effect on EC50 values (1 μM AF2 EC50 control: 0.16 μM ± 0.13, n = 10 preparations, DF = 87; 1 μM AF2 + 0.1 μM ryanodine EC50 0.13 μM ± 0.07, n = 10 preparations, DF = 87 p< 0.05).

3.4 Ryanodine inhibits AF2 potentiated levamisole contractions

AF2 potentiates the contraction responses by decreasing the EC50 without significant effect on gmax, Fig. 2C. AF2 also prolongs the duration of electrophysiological responses of levamisole in A. suum [17]; it increases the opening of voltage-activated calcium channels [8] and has been suggested to stimulate RyRs [8; 14]. Stimulation of RyRs may not increase gmax, the maximum force of contraction, if its upper limit is determined by the contractile elements. It was of interest to examine the effects of ryanodine on AF2 potentiated levamisole contractions. We found that ryanodine, Fig. 3C, significantly reduced gmax but had little effect on EC50 values.

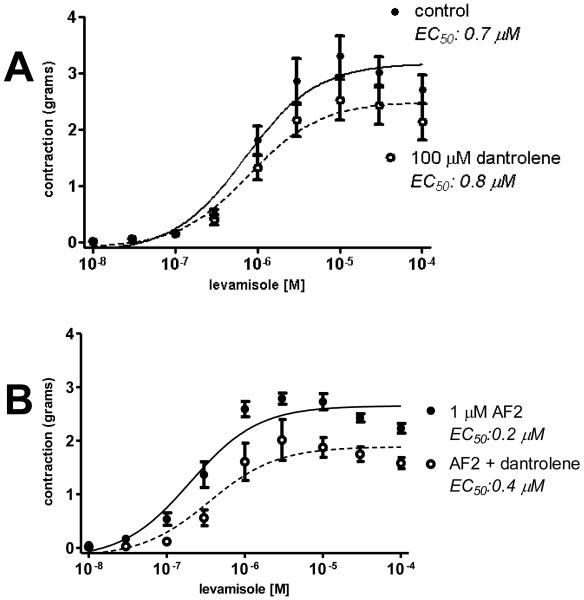

3.5 Effects of dantrolene on contraction

Dantrolene depresses excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle, binds to RyRs and inhibits calcium release [18]. In A. suum, dantrolene was not potent and high concentrations were necessary to see an effect. Fig. 4A shows the effect of 100 μM dantrolene on levamisole responses. 100 μM dantrolene significantly reduced gmax from 3.2 to 2.5 g. The EC50 was not affected (control EC50 0.7 μM; in 100 μM dantrolene the EC50 was 0.8 μM). The inhibitory effects of dantrolene, like those of ryanodine, are consistent with a role for RyRs in affecting gmax of levamisole-mediated contractions but with little effect on EC50.

Fig. 4.

Inhibitory effect of dantrolene on levamisole-concentration contraction plots.

A: 100 μM dantrolene reduced gmax from 3.17 ± 0.15 g (control, n = 6 preparations, DF = 51) to 2.49 ± 0.15 g (n = 6 preparation DF = 51), p < 0.05. The EC50 was not affected (control EC50 0.7 μM; in 100 μM dantrolene the EC50 was 0.8 μM, p > 0.05).

B: Effect of 100 μM dantrolene on AF2-potentiated levamisole contractions. The control AF2 gmax was reduced from 2.6 ± 0.08 g (n= 6 preparations, DF = 51) to 1.89 ± 0.12 g (1 μM AF2 + 100 μM dantrolene, n = 5 preparations, DF = 42), p < 0.05. The AF2 control EC50 was 0.20 μM and in the presence of dantrolene, the EC50 was 0.35 μM, p > 0.05.

We then tested the effect of 100 μM dantrolene on AF2-potentiated levamisole contractions and found that dantrolene had an inhibitory effect on gmax. The control AF2 gmax was significantly reduced from 2.6 g to 1.9 g (1 μM AF2 + 100 μM dantrolene), Fig. 4B. However, 100 μM dantrolene did not significantly reverse the sensitizing effect of AF2 on the levamisole EC50. The AF2 control EC50 was 0.20 μM and in the presence of dantrolene, the EC50 was 0.35 μM, but was not significantly different. The dantrolene observations are similar to the observations made with ryanodine.

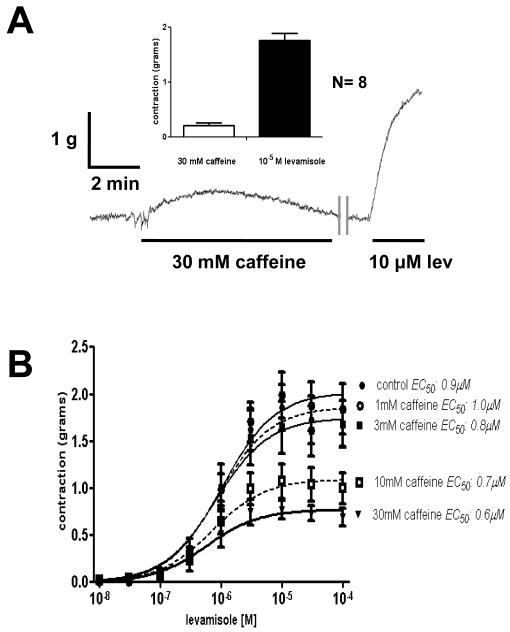

3.6 Effects of caffeine on levamisole induced contractions

High mM concentrations of caffeine sensitize calcium-induced calcium release channels (RyRs) to the effects of calcium [19] and will, with time, like ryanodine lead to depletion of calcium stores in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Initially, we applied 3 – 30 mM concentrations of caffeine to see if we could obtain contractions due to opening of RyRs. We found that caffeine was not potent at producing contractions and that 30 mM caffeine produced a mean contraction of only 0.2 g in 8 preparations, Fig. 5A. The force of contraction produced by 30 mM caffeine was much smaller (< 0.3 g) than that produce by 10 μM levamisole ( > 1 g) in the same preparations.

Fig. 5.

Effects of caffeine.

A: Caffeine, 30 mM produces a small desensitizing contraction which is much smaller than that produced by 10 μM levamisole in the same preparation.

B: Effect of 30 min caffeine on levamisole cumulative concentration contraction plots. Caffeine produced a concentration dependent reduction in the maximum force, gmax, without effect on the levamisole EC50. 30 mM caffeine reduced the maximum contraction from 1.86 ± 0.11 g (control, N = 8 preparations, DF = 88) to 0.77 ± 0.05 g (30 mM caffeine, n = 4 preparations, DF = 34, p < 0.05). There was no significant effect on the EC50 (0.9 to 0.6 μM, p > 0.05).

Interestingly, caffeine was more effective at inhibiting the amplitude of levamisole contractions in our A. suum muscle flaps. We applied caffeine in different concentrations for 30 minutes before we examined effects of levamisole contraction. We found, Fig. 5B, that caffeine produced a concentration-dependent reduction in the maximum force of contraction gmax, but was without effect on the EC50. For example, 30 mM caffeine significantly reduced the maximum contraction from 1.9 g to 0.8 g, Fig 5 B. There was no significant effect on the EC50 (0.9 to 0.6 μM). These observations mimic the effects of ryanodine in A. suum and indicate a role for RyRs in modulating the maximum force of levamisole-induced contraction but do not indicate an effect on EC50. We can also see from these observations that caffeine does not mimic the effect of AF2.

4. Discussion

4.1. A. suum muscle contraction is not like regular striated muscle but more like smooth muscle

The body muscle of A. suum, like other nematodes, is obliquely striated [12; 13; 20] and contains thin- and thick-filament linked calcium regulatory systems. An increase in cytoplasmic calcium therefore will produce hydrolysis of ATP by myosin-like ATPases that causes the thin filaments to slide past myosin-containing thick filaments to shorten the sarcomeres [20]. The fact that contraction is graded and not all-or-none makes the muscle unlike regular vertebrate striated muscle or cardiac muscle [21]. Although there are calcium action potentials in A. suum [8; 22], contraction of the muscle cells does not follow single action potentials or single slow depolarization waves, but are associated with longer lasting modulation, ~ 10 s waves [23].

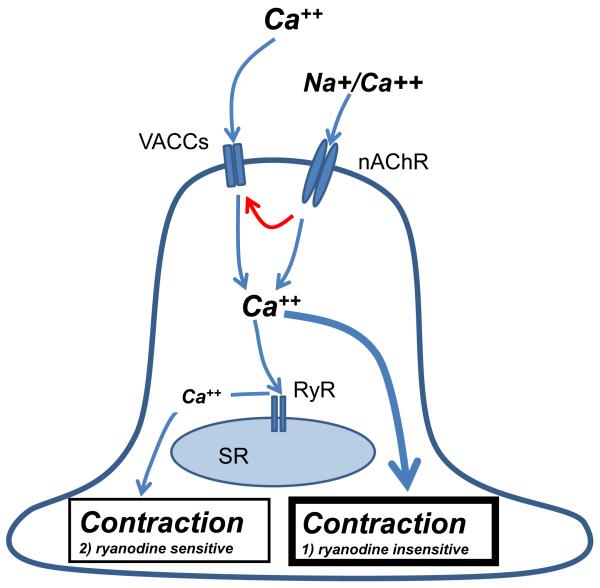

Our observations in Fig. 2A & B show in A. suum that extracellular calcium is a requirement for contraction; intracellular calcium stores are not sufficient to permit contraction as in regular vertebrate skeletal muscle. In vertebrate smooth muscle excitation contraction, coupling [24] is due to: 1) an initial rise in cytoplasmic calcium that can be triggered by receptor stimulation; 2) an additional increase in cytoplasmic calcium due to release from sarcoplasmic reticulum via RyRs and; 3) a continued extracellular calcium entry through membrane channels for continued contraction [25]. In A. suum muscle, there are parallels, Fig. 6. Firstly, levamisole activates nAChR channels [23] which can allow entry of calcium and an initial rise in cytosolic calcium. Following nAChR activation, there is depolarization of the membrane potential that activates voltage-activated calcium channels [8] and voltage-sensitive slow waves [22] allowing further entry of calcium. The rise in cytosolic calcium opens the A. suum RyRs leading to further calcium increase. In the continued presence of levamisole calcium entry into the muscle cell is maintained through open nAChRs [26] and voltage-activated channels.

Fig. 6.

Summary diagram of the proposed components involved in the modulatory effects of RyRs on contraction. Levamisole activates nAChRs that are permeable to calcium and that produce depolarization and activate voltage-gated calcium channels and slow wave channels (solid red arrows) giving rise to further entry of calcium (solid blue arrows). Opening of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), voltage-gated calcium channels (VACCs) and sodium/calcium permeable slow wave channels (not shown for simplicity) lead to an increase in cytosolic calcium. There is a ryanodine sensitive and a ryanodine insensitive pathway that leads to an increase in cytosolic calcium and contraction.

4.2. Effects of ryanodine, caffeine and dantrolene on RyRs

In C. elegans the muscle RYRs are found in the vesicle-like sarcoplasmic reticulum close to the plasma membrane and which surround the dense bodies where the thin-filaments are attached [9; 10; 11] and where RyRs release calcium. Ryanodine binding sites purified from C. elegans have been incorporated into bilayers where they form ryanodine-sensitive, calcium-permeable channels like those of mammalian cardiac muscle [16; 18]. Ryanodine opens C. elegans RyRs channels [10; 11] as it does in the rabbit heart and fixes them in a subconductance state depleting their SR of calcium [28]. We used similar concentrations of ryanodine in our studies on A. suum so that effects on the RyRs are expected to be similar. There is only a single copy of the RyR gene (unc-68) in C. elegans. Mutant unc-68 C. elegans move slowly, suggesting that RyRs modulate the rise in cytoplasmic reticulum but that the cytoplasmic calcium increase is only partly mediated by the ryanodine pathway.

These observations on C. elegans parallel our observations with A. suum contraction where ryanodine affected only part of the levamisole induced contraction. We observed that the application of ryanodine did not produce contraction in A. suum suggesting that emptying of the SR by ryanodine does not produce a sufficient or effective rise in cytosolic calcium for contraction. The lack of contraction might be due to the slow time-course of bath-applied ryanodine in A. suum that could allow homeostatic mechanisms like a Na-Ca exchanger [29] to limit any rise in cytosolic calcium. Once the calcium from the SR has been depleted, there can no longer be a calcium-induced-calcium release.

The calcium sensitivity of vertebrate RyRs preparations is increased by caffeine [30]. Caffeine is used experimentally to induce emptying of the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium stores. We observed that high 30 mM concentrations of caffeine produced a small contraction: an effect consistent with emptying of the sarcoplasmic calcium stores. Interestingly, we found that caffeine produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of the levamisole gmax without effect on the levamisole EC50. This effect mimicked the effect of ryanodine and was consistent with caffeine and ryanodine depleting SR calcium. The caffeine-induced contractions were small compared with that produced by levamisole that is explained by RyRs contributing only part of the calcium pool for contraction. Dantrolene is a RyR antagonist [30] that is used clinically to treat malignant hyperthermia [18]. We found that it too mimicked the effects of ryanodine, but it was less potent. It is clear from our observations on the effects of ryanodine, dantrolene and caffeine, that agents that affect the RyR of a parasitic nematode, modulate the force of levamisole contractions but were without significant effect on EC50s.

4.3 The response to levamisole, ryanodine receptors and levamisole resistance

Our model, Fig. 6, explains our observations and illustrates a role for RyRs in the excitation-contraction pathway in A. suum. Our experiments showed us that the force of the levamisole-concentration contraction response is approximated by equation 1 that has three parameters: 1) the concentration of levamisole; 2) gmax, the maximum force of contraction; and 3) the levamisole EC50. Factors that change these three parameters will affect the parasite contraction to anthelmintic treatment of the host animal.

The concentration of the levamisole reaching the nematode parasite and affecting the response depends on the dose of anthelmintic administered and pharmacokinetic parameters that govern the concentration-time relationship. An increase in levamisole dose will increase the concentration of levamisole reaching the receptors in the parasite and increase the force of the body muscle contraction. Our experiments showed that the extracellular calcium concentration and influences on the RyRs (ryanodine, caffeine and dantrolene) affected gmax and the force of contraction, with little effect on the levamisole EC50. AF2 affected the force of contraction by decreasing the EC50 without increasing gmax. We show in our subsequent paper that one of the actions of AF2 is to sensitize the RyRs receptors and in these contraction studies, we have shown that inhibition of RyRs leads to a reduction in gmax. The question then is: ‘Why does AF2 not increase gmax?’ One possible explanation is that the upper limit on gmax is determined by the contractile elements; once these are contracted maximally, additional calcium will not increase the maximum force of contraction.

The sensitivity of gmax to the concentration of calcium in the extracellular milieu suggests that if calcium were increased by a dietary calcium supplement to the host animal, it might potentiate the therapeutic action of levamisole on a parasitic nematode in the GI tract. The concentration of free calcium in the intestine of the pig varies between 2 – 27 mM [27] and is sensitive to the amount of calcium in the diet. The affect of AF2 on the levamisole EC50 suggests that a small molecule AF2-mimetic would potentiate the effect of levamisole if it were at a sub maximal concentration [8].

The genes causing levamisole resistance in the different parasitic nematodes remain to be identified but forward and reverse mutation experiments starting with Lewis et al. [31] have identified candidate genes in C. elegans associated with resistance to levamisole [31 - 40] and Wormbase, (www.wormbase.org). These candidate genes will affect the parameters of equation 1 and mutant genes that reduce the function of the muscle contractile elements or the RyRs (unc-68) are expected to reduce gmax. We have seen using muscle contraction experiments that RyRs modulate the maximum force of levamisole muscle contraction and that null-mutants of unc-68 are associated with levamisole resistance in C. elegans; it is possible that mutants of RyRs will also be involved in levamisole resistance in parasite isolates. In our subsequent paper, we use electrophysiological experiments to investigate the effects of levamisole, RyRs and AF2.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by Grant Number R 01 AI 047194 from the national Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to RJM and by an Iowa Center for Advanced Neurotoxicology to APR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Wolstenholme AJ, Fairweather I, Prichard R, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Sangster NC. Drug resistance in veterinary helminths. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aceves J, Erlij D, Martinez-Maranon R. The mechanism of the paralyzing action of tetramisole on Ascaris somatic muscle. Br J Pharmac. 1970;38:602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Robertson SJ, Martin RJ. Levamisole-activated single-channel currents from muscle of the nematode parasite Ascaris suum. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Qian H, Martin RJ, Robertson AP. Pharmacology of N-, L- and B-Subtypes of nematode nAChR Resolved at the Single-Channel Level in Ascaris suum. FASEB J. 2006;20:E2108–E2116. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6264fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Martin RJ, Robertson AP. Mode of action of levamisole and pyrantel, anthelmintic resistance, E153 and Q57. Parasitology. 2007;134:1093–1104. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Qian F, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. Levamisole resolved at the single-channel level in C. elegans. FASEB J. 2008;22:3247–3254. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burr AH, Gans C. Mechanical significance of obliquely striated architecture in nematode muscle. Biol Bull. 1998;194:1–6. doi: 10.2307/1542507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Verma S, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. The nematode neuropeptide, AF2 (KHEYLRF-NH(2)), increases voltage-activated calcium currents in Ascaris suum muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:888–899. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stevenson TO, Mercer KB, Cox EA, Szewczyk NJ, Conley CA, Hardin JD, Benian GM. Unc-94 encodes a tropomodulin in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:936–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maryon EB, Saari B, Anderson P. Muscle-specific functions of ryanodine receptor channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2885–2895. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maryon EB, Coronado R, Anderson P. unc-68 encodes a ryanodine receptor involved in regulating C. elegans body-wall muscle contraction. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:885–893. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rosenbluth J. Ultrastructure of somatic muscle cells in Ascaris lumbricoides. II. Intermuscular junctions, neuromuscular junctions, and glycogen stores. J Cell Biol. 1965;26:579–591. doi: 10.1083/jcb.26.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosenbluth J. Ultrastructural organization of obliquely striated muscle fibers in Ascaris lumbricoides. J Cell Biol. 25:495–515. doi: 10.1083/jcb.25.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Trailovic SM, Clark CL, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. Brief application of AF2 produces long lasting potentiation of nAChR responses in Ascaris suum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;139:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sattelle DB, Cordova D, Cheek TR. Insect ryanodine receptors: molecular targets for novel pest control chemicals. Invert Neurosci. 2008;8:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s10158-008-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim YK, Valdivia HH, Maryon EB, Anderson P, Coronado R. High molecular weight proteins in the nematode C. elegans bin [3H] yanodine and form a large conductance channel. Biophys J. 1992;63:1379–1384. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81702-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Reinitz CA, Herfel HG, Messinger LA, Stretton AOW. Changes in locomotory behavior and cAMP produced in Ascaris suum by neuropeptides from Ascaris suum or Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biochem Parsitol. 2000;111:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F. Dantrolene--a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:64–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ozawa T. Ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release mechanism in non-excitable cells (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2001;7:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Anderson P. Molecular genetics of nematode muscle. Ann Rev Genet. 1989;23:507–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.002451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ogawa Y, Kurebayashi N, Murayama T. Putative roles of type 3 ryanodine receptor isoforms (RyR3) Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].del Castillo CJ, De Mello WC, Morales T. The initiation of action potentials in the somatic musculature of Ascaris lumbricoides. J Exp Biol. 1967;46:263–279. doi: 10.1242/jeb.46.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weisblat DP, Byerly L, Russel RL. Ionic Mechanisms of electrical activity in the somatic muscle cell of the nematode Ascaris lumbricoides. J Comp Physiol. 1976;111:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Berridge MJ. Smooth muscle cell calcium activation mechanisms. J Physiol. 2008;586:5047–5061. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Albert AP, Saleh SN, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Multiple activation mechanisms of store-operated TRPC channels in smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:25–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Williamson SM, Robertson AP, Brown L, Williams T, Woods DJ, Martin RJ, Sattelle DB, Wolstenholme AJ. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum: formation of two distinct drug targets by varying the relative expression levels of two subunits. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000517. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000517. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hobson AD, Stephenenson W, Eden A. Studies on the physiology of Ascaris lumbricoides II. The inorganic composition of the body fluid in relation to that of the environment. J Exp Biol. 1952;29:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Du GG, Guo X, Khanna VK, MacLennan DH. Ryanodine sensitizes the cardiac Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor isoform 2) to Ca2+ activation and dissociates as the channel is closed by Ca2+ depletion. PNAS. 2001;98:13625–13630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241516898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dipolo R, Beaugé L. Sodium/calcium exchanger: Influence of metabolic regulation on ion carrier interactions. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:155–203. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xu L, Tripathy A, Pasek DA, Meissner G. Potential for pharmacology of ryanodine receptor/calcium release channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;853:130–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lewis JA, Wu CH, Berg H, Levine JH. The genetics of levamisole resistance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1980;95:905–928. doi: 10.1093/genetics/95.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Benian GM, L’Hernault SW, Morris ME. Additional sequence complexity in the muscle gene, unc-22, and its encoded protein, twitchin, of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;134:1097–1104. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kagawa H, Takuwa K, Sakube Y. Mutations and expressions of the tropomyosin gene and the troponin C gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:213–218. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fleming JT, Squire MD, Barnes TM, Tornoe C, Matsuda K, Ahnn J, Fire A, Sulston JE, Barnard EA, Sattelle DB, Lewis JA. Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole resistance genes lev-1, unc-29, and unc-38 encode functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5843–5857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05843.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jones AK, Sattelle DB. Functional genomics of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Bioessays. 2004;26:39–49. doi: 10.1002/bies.10377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Culetto E, Baylis HA, Richmond JE, Jones AK, Fleming JT, Squire MD, Lewis JA, Sattelle DB. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-63 gene encodes a levamisole-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42476–42483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gally C, Eimer S, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL. A transmembrane protein required for acetylcholine receptor clustering in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2004;431:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature02893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Towers PR, Edwards B, Richmond JE, Sattelle DB. The Caenorhabditis elegans lev-8 gene encodes a novel type of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Touroutine D, Fox RM, Von Stetina SE, Burdina A, Miller DM, Richmond JE. acr-16 encodes an essential subunit of the levamisole-resistant nicotinic receptor at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27013–27021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jones AK, Buckingham SD, Sattelle DB. Chemistry-to-gene screens in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nrd1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]