Abstract

Formins, proteins defined by the presence of an FH2 domain and their ability to nucleate linear F-actin de novo, play a key role in the regulation of the cytoskeleton. Initially thought to primarily regulate actin, recent studies have highlighted a role for formins in the regulation of microtubule dynamics, and most recently have uncovered the ability of some formins to coordinate the organization of both the microtubule and actin cytoskeletons. While biochemical analyses of this family of proteins have yielded many insights into how formins regulate diverse cytoskeletal reorganizations, we are only beginning to appreciate how and when these functional properties are relevant to biological processes in a developmental or organismal context. Developmental genetic studies in fungi, Dictyostelium, vertebrates, plants and other model organisms have revealed conserved roles for formins in cell polarity, actin cable assembly and cytokinesis. However, roles have also been discovered for formins that are specific to particular organisms. Thus, formins perform both global and specific functions, with some of these roles concurring with previous biochemical data and others exposing new properties of formins. While not all family members have been examined across all organisms, the analyses to date highlight the significance of the flexibility within the formin family to regulate a broad spectrum of diverse cytoskeletal processes during development.

Keywords: formin, development, cytoskeleton, cytokinesis, polarity, actin, microtubule, actin nucleation, Diaphanous, Daam, Cappuccino, Spire

1. Introduction: Formins in development

The formin protein family participates in actin cytoskeleton remodeling through regulation of actin filament assembly; actin filaments are generated de novo by nucleation from a pool of monomeric actin. By regulating this rate-limiting step of actin polymerization, formins can directly modulate the rate of F-actin production [1-5]. Formins have been found in all eukaryotes examined [6]; these multidomain proteins are conserved from plants to fungi and vertebrates. Formin family members are involved in diverse processes relying on actin and microtubule cytoskeleton reorganization including formation of filopodia and lamellipodia, establishment of cell polarity, cytokinesis, vesicular trafficking, formation of adherens junctions, embryonic development, and signaling to the nucleus (reviewed in [2, 5, 7]; see accompanying reviews in this special issue [8-15]).

Formins represent one of the five currently recognized de novo actin nucleation factor classes, each having their specific role in actin polymerization and employing different mechanisms to accomplish their task [16-22]. Formins nucleate formation of linear (unbranched) actin filaments through actin dimer stabilization and processive movement with the elongating filament (fast-growing) barbed end [23-25]. The other four classes of de novo actin nucleators are the Arp2/3 complex, Spire, Cordon bleu, and the recently described leiomodin [16, 19, 22, 26]. Arp2/3 binds to the sides of preexisting actin filaments and nucleates branched actin networks upon activation by WASP family members (reviewed in [26]). Spire nucleates the assembly of unbranched actin filaments through formation of a prenucleation complex containing up to four actin monomers, and, like the Arp2/3 complex, remains bound to the pointed ends of nucleated filaments [19]. Cordon bleu nucleates linear actin filaments at the fast-growing actin filament barbed ends, similar to formins, but does so through formation of a trimeric actin nucleus [16]. Leiomodin nucleates linear actin filaments in muscle cells, and is thought to do so through the formation of a trimeric actin nucleus at the pointed end of nucleated filaments [22]. Interplay between the various de novo actin nucleators, as well as actin depolymerization factors, is required in order to elicit temporal and spatial remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, which underlies complex cellular functions.

Formin proteins have been shown to regulate processes governing both individual cell and tissue architecture via dynamic remodeling of the actin and/or microtubule cytoskeletons. While much progress has been made in studies of formin biochemical properties and cell biology, the function of formins and their roles in various processes in the context of the whole organism remains less well understood. This review focuses on developmental and genetic insights gained from formin studies conducted in the context of both single cell and multicellular organisms. We survey formin knockout studies in various species, examine an example of the complexity of formin interactions with other actin nucleators and the actin-microtubule cytoskeleton as highlighted by recent work in Drosophila, and summarize the lessons learned from developmental studies uncovering the biological manifestations of formin function in complex organisms.

2. Evolutionary Considerations: Formin a family tree

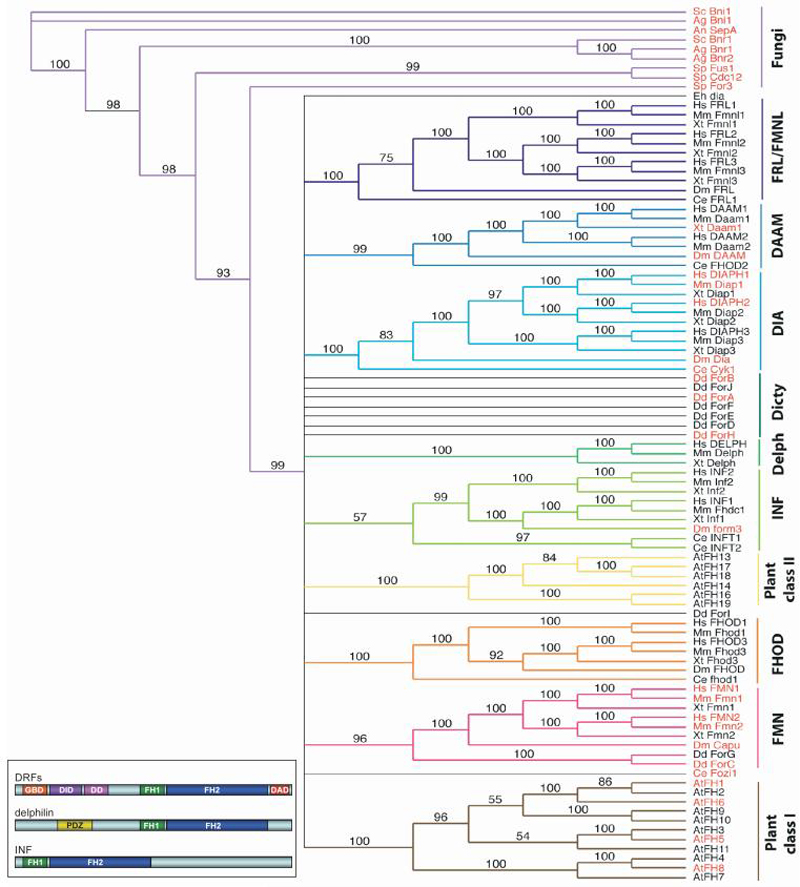

The Formin Homology 2 (FH2) domain is the defining feature of the formin protein family. This domain is well conserved and sufficient for many of the effects of formins on actin (reviewed in [5]). Over 100 formin family members in diverse eukaryotic species have been described and predicted based on the presence of the FH2 domain [6, 27]. Several other domains have been defined in formins, including the Formin Homology 1 and 3 domains (FH1 and FH3), a GTPase binding domain (GBD), and the Diaphanous auto-regulatory domain (DAD), but not all of the formins possess them. Phylogenetic analysis of the FH2 domain, as well as the additional conserved regions in formins from diverse organisms, has led to classification of formin family into phylogeny-based groups [6]. Metazoan formins segregate into 7 groups: DIA, FMN, FHOD, delfilin, INF, FRL, and DAAM (Fig. 1). The DIA, DAAM, FRL, FHOD and delfilin groups possess strong group-specific similarities outside of the FH2 domain, supporting the FH2-based groupings. Non-metazoan formins form their own separate groups based on the FH2 domain comparisons. It should be noted, however, that regions of similarity outside of the FH2 domain linking three metazoan groups (DIA, DAAM, and FRL) with Dictyostelium and fungal formins have also been identified and might reflect differences in evolutionary pressures acting on the FH2 domain and non-FH2 regions.

Fig. 1. An unrooted phylogenetic tree of formins based on FH2 domain alignment.

FH2 domain sequences from human (Hs), mouse (Mm), frog (Xt), fly (Dm), worm (Ce), slime mold (Dd), fungi (Sc, Sp, Ag, An), amoeba (Eh), and plant (At) formins were aligned using Multialin [199] (see Supplemental Information, Fig. S1). Distance analysis of the FH2 domain alignment was performed with PAUP* 4.0 [200], using minimal evolution as the optimally criterion, and mean character difference as the distance measure. Bootstrap values were calculated over 1000 iterations. Colors indicate clades supported by high bootstrap values and corresponding to known formin classes (indicated on the right). Branch lengths do not depict evolutionary distance. Accession numbers of sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses are listed in Supplemental Information, Table S1. Formins that have been analyzed in a developmental context and discussed in this review are highlighted in red. (Inset, lower left) Schematic representation of the domain organization from representative formin classes.

The similarity outside of the FH2 domain among formins has been linked to their regulation and underlies their subdivision into functional groups (see accompanying review in this special issue [15]). The most extensively studied group to date is the Diaphanous-related formins (DRFs), which act as direct effectors of Rho family GTPases [28-31] (reviewed in [7, 32]). The DRFs include the metazoan DIA, DAAM, and FRL formins, and the yeast Bni1, Bnr1, and SepA. The domain architecture of DRF proteins is preserved and contains two parts: a C-terminal region, which is directly involved in actin assembly, and an N-terminal regulatory region, which mediates an intramolecular interaction with the C terminus to maintain DRFs in an auto-inhibited state (Fig. 1 inset).

The C-terminal half of DRFs contains three structural and functional elements: the profilin-binding FH1 domain, the actin-binding FH2 domain, and the Diaphanous Auto-regulatory Domain (DAD) motif (reviewed in [5, 32]). The N-terminal part includes a GTPase-binding domain (GDB), which binds Rho-family GTPases in their activated (GTP bound) state, the Diaphanous Inhibitory Domain (DID), which binds the C-terminal DAD motif, and the dimerization domain (DD). These domains were originally defined from primary sequence conservation [5], and subsequently refined using structural and biochemical analyses of mDia1 [33-35]. The GBD and FH3 domains defined by sequence analysis correspond to the structural GBD plus a portion of DID, and the remainder of the DID plus the DD, respectively [2].

Other (non-DRF) formins also have distinct domain architecture. The FMN and FHOD classes of formins have FH1 and FH2 domains at their C termini, but they lack a recognizable GBD/FH3 domain in their N-terminal regions. It should be noted, however, that Drosophila Cappuccino (FMN class) has been shown to interact with activated Rho through an N-terminal domain [36], and that the N- and C-terminal segments of mammalian formin I (FMN class) interact with each other [37], features that are more characteristic of DRFs.

The Delfilin and INF formin classes contain conserved motifs in addition to their FH1 and FH2 domains. Delfilin has an N-terminal PDZ domain, which has been linked with glutamate receptor signaling [38, 39]. INF class proteins contain a DAD motif that has sequence similarity to WASp-homology 2 (WH2) domains and strongly binds actin monomers [40]. Neither one of the two plant formin classes, which include over 20 Arabidopsis thaliana formins identified using bioinformatics, resemble DRFs [41].

Despite over 100 formin family members having been identified or predicted in diverse eukaryotic species, only a handful have been characterized in a developmental or organismal context. The studies to date of formins representing different classes in both unicellular and multicellular organisms highlight their phylogenetic and functional groupings by revealing common as well as non-redundant functions. As such, formins have now been suggested to play central roles in an impressive subset of fundamental cellular events including cytoskeletal coordination and dynamics, cell polarity, cell adhesion, cell morphology, cell motility, and cytokinesis, as well as in morphogenetic events central to the proper development of multicellular organisms.

3. Genetic and Developmental Insights from unicellular organisms

Fungal Formins

Fungal formins have been shown to play important roles in cell polarity, actin cable assembly, and cytokinesis (Table 1) [42-51]. The two formins of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, bud neck involved (Bni1) and Bni-related (Bnr1), together are required for polarized bud formation and cell viability [43, 52]. Mutants with a deletion of the bni1p gene have defects in polarized morphogenesis, in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton during the mating pheromone response, and in the initial movement of the spindle pole body (SPB) towards the emerging bud [28, 49, 53]. Disruption of the bnr1 gene results in axial budding-specific randomization of the budding pattern [46]. During bud emergence, Bni1p localizes to the bud tip and is responsible for generating actin cables specific to the bud. At the same time, Bnr1p localizes to the bud neck and generates a complementary set of cables in the mother [43, 48]. Based on mutant studies neither set of cables alone is critical for cell function, but loss of both is lethal (Fig. 2A) [52, 54].

Table 1.

Phenotypes and Proposed Functions of Formin Mutants Characterized to Date

| Organism Name | Formin Class | Expression Pattern | Proposed Function(s) | Mutant Phenotype(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNICELLULAR ORGANISMS | |||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | |||||

| Bnilp | bud neck and tip | -cell polarity | -viable with defects in polarized morphogenesis | [29,42, 53] | |

| -cytokinesis | -actin cytoskeleton reorganization | ||||

| -actin cable formation | -initial movement of the spindle pole body towards the emerging bud | ||||

| -inviable in combination with bnr1 | |||||

| Bnr1p | bud neck | -cell polarity | -axial budding-specific randomization of the budding pattern | [29,43,51] | |

| -cytokinesis | |||||

| -actin cable formation | -inviable in combination with bni1, severe temperature growth | ||||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | |||||

| Cdc12p | cell division ring | -cytokinesis | [29,43,46, 51,55] | ||

| -defects in ring and septum formation | |||||

| For3p | cell tips | -cell polarity | -loss of actin cables | [45] | |

| cell division site | -actin cable formation | -loss of polarized cell growth | |||

| -abnormal microtubules organization | |||||

| Fus1 | projection tips | -mating | -conjugation block | [47, 54] | |

| -membrane fusion | |||||

| Aspergillus nidulans | |||||

| SepA | hyphal tips, septation site | -cell polarity | -failure to septate | [48,49] | |

| -cytokinesis | -defects in conidiation | ||||

| Ashybya gossypii | |||||

| Bni1p | hyphal tips | -cell polarity | -fails to develop hyphae | [50] | |

| -actin cables | -expands to potato-shaped giant cells lacking actin cables | ||||

| Bnr1p | ? | ? | -viable, wildtype-like growth | [50] | |

| -inviable in combination with bnr2 | |||||

| Bnr2p | ? | ? | -viable, wildtype-like growth | [50] | |

| -inviable in combination with bnr1 | |||||

| Dictyostelium discoideum | |||||

| ForA | -none observed upon disruption or when doubly mutant with ForB | [57] | |||

| ForB | -none observed upon disruption or when doubly mutant with For A | [57] | |||

| ForC | crown (macropinocytotic cups), micropinosomes, edges of cells | -multicellular adhesion | -cannot lift sori to top of fruiting body stalk | [57] | |

| -multicellular actin remodeling | -abberant fruiting bodies with short stalks and unlifted sori | ||||

| -failure to migrate as slugs | |||||

| ForH/dDia2 | DIA | filopodial tips | -filopodia formation and maintenance | -reduced filopodial number and length | [58] |

| -cell adhesion | -increased motility | ||||

| -reduced surface contact | |||||

| -cytoskeletal defects at the unicellular stage | |||||

| VERTEBRATES | |||||

| Xenopus laevis | |||||

| Daam1 | DAAM | broad expression, including CNS and tissues requiring Wnt signaling | -Wnt PCP Signaling intermediate | -inhibition of elongation | [92,93,95] |

| -actin cytoskeleton remodeling | -gastrulation defects | ||||

| -embryonic movement | |||||

| Danio rerio (zebrafish) | |||||

| Dia | DIA | CNS? | -affects gastrulation and convergent extension by Wnt-RhoA signaling pathway | -no loss-of-function phenotype reported | [91] |

| -over-expression suppresses convergent extension defects associated with RhoA mutant | |||||

| Daam1 | DAAM | notochord vesicles within notochord | -endocytosis of EphB during notochord convergent extension | -short body axis | [97] |

| -kinked tail | |||||

| -cyclopia (by NDaam1 over-expression) | |||||

| Mus musculus | |||||

| Formin-1 | FMN | developing nervous system and kidney | -possibly kidney morphogenesis | -No lethal defects associated with formin-1 specific mutants | [61,62,67] |

| Formin-2 | FMN | developing mouse and adult CNS | Meiosis defects in: | -female hypofertility | [69-71,145] |

| -spindle migration | |||||

| -polar body extrusion | |||||

| -cytokinesis | |||||

| mDia1 | DIA | T-cells, other hematopoeitic cells | -adherence | -defects in T cell development and function | [84-86] |

| -migration | -defects in myelopoiesis and erythropoiesis | ||||

| -trafficking | |||||

| -response to chemotactic/ proliferative signals | |||||

| Homo sapiens | |||||

| DIAPH1 | DIA | ubiquitous | -hair cell actin cytoskeleton maintenance | -autosomal domininant, nonsyndromic deafness (DFNA1) | [89] |

| DIAPH2 | DIA | ubiquitous (3 transcripts), adult testis (1 transcript) | -oogenesis | -premature ovarian failure | [90] |

| GENETIC MODEL ORGANISMS | |||||

| Drosophila melanogaster | |||||

| Diaphanous | DIA | cleavage furrows, contractile rings during cytokinesis | -formation and/or activity of the contractile ring during cytokinesis | -inability to cellularize during embryogenesis | [100-102] |

| -regulator of membrane invagination | -absent imaginal discs | ||||

| -multinucleate spermatids | |||||

| -binucleate follicle cells | |||||

| -polyploid larval neuroblasts | |||||

| Cappuccino | FMN | ubiquitous in the oocyte and nurse cells, but enriched at the cortex | -regulates the timing of ooplasmic streaming by maintaining cytoskeletal organization in the oocyte | -defects in anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral patterning and segmentation | [103-106] |

| -abnormal cellularization | |||||

| -premature ooplasmic streaming | |||||

| DAAM | DAAM | - | -organizes actin into parallel bundles in the tracheal system that specify taenidial folds | -tracheal tube collapse and disorganization | [107] |

| -required for proper tracheal patterning | -failure to secrete cuticle in the trachea | ||||

| Formin3 | INF | not fully determined, but may be restricted to tracheal cells | -assembly of actin tracks required for cell shape changes | -failure or delay in fusion events of tracheal branches | [108] |

| -actin reorganization necessary for tracheal fusion | |||||

| Caenorhabditis elegans | |||||

| Cyk-1 | DIA | leading edge of cleavage furrow formation | -regulation of cytokinesis and cellularization by formation of contractile ring | -oocytes do not cellularize | [109,110] |

| -absent pseudocleavage furrows | |||||

| -polar bodies not extruded (meiosis) | |||||

| -incomplete cytokinesis | |||||

| PLANTS | |||||

| Arapidopsis thaliana | |||||

| AtFH1 | type-I | cell membrane | -regulation of pollen tube growth | -slight increases in activity stimulate pollen tube growth | [152] |

| -further overexpression leads to growth arrest | |||||

| AtFH4 | type-I | cell to cell contact points or junctions | -multicellular adhesion | ||

| AtFH5 | type-I | cell plate during mitosis | -regulation of cytokinesis | -delay in endosperm cellularization | [148] |

| AtFH6 | type-I | cyst in posterior endosperm | -regulation of cytoskeletal tracks for directed transportation | -disruption of endosperm cyst ontogenesis | [153] |

| A1FH8 | type-I | transverse cell walls, cytoplasm | -cell expansion | -arrest in root hair development | [150,151] |

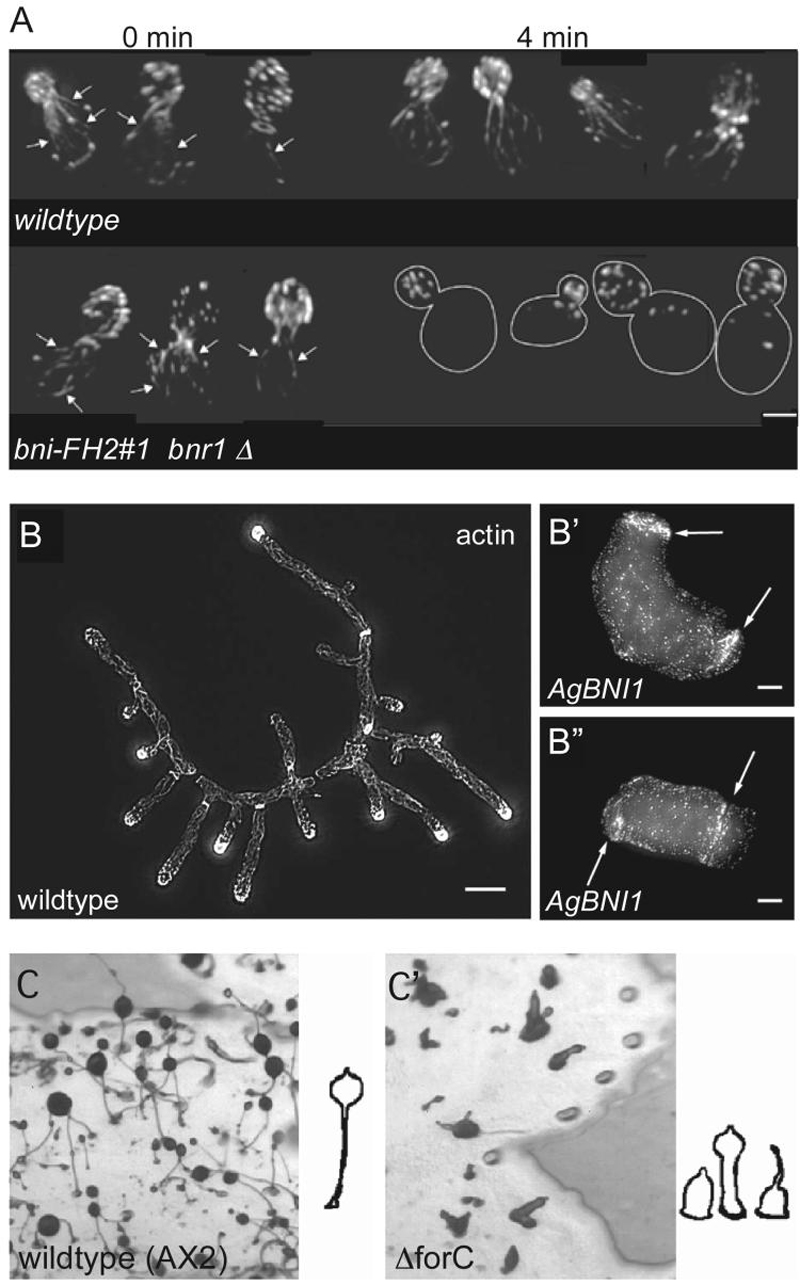

Fig. 2. Different roles of formins in unicellular organisms.

(A) Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells mutant for bni1 and bnr1 cannot maintain actin cables as visualized by phalloidin staining. After the switch to a non-permissive temperature, these structures are quickly lost. Figure adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Sagot et al. (2002) Nature Cell Biology 4:42-50 [49].

(B-B") Ashbya gossypii spores containing a deletion of AgBNI1 (B'-B") are unable to initiate hyphal growth compared to wildtype (B). Instead, these mutant spores maintain irregular, apolar growth to form giant irregular cells. Actin, as visualized by phalloidin staining, is not polarized as in wild-type. Figure adapted and reprinted with permission of the American Society for Cell Biology, from Schmitz et al. (2005) Molecular Biology of the Cell 17:130-145 [50]; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

(C-C') Aberrant fruiting bodies are produced by Dicytostelium discoideum mutant for forC (C') compared to wildtype (C). Figure adapted from Kitayama and Uyeda (2002) Journal of Cell Science 116:711-723 [58], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

Three formins have been identified in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe: For3p, Cdc12p, and Fus1p. Similar to budding yeast formins, these pombe formins play important roles in cytokinesis, cell polarity, and cell fusion (Table 1) [42, 44, 55] (also see [10] in this special issue). for3 null mutant cells exhibit a loss of actin cable assembly at cell tips, loss of polarized cell growth, and abnormal organization of their cytoplasmic microtubules [44]. Cdc12p is involved in cytokinesis, where it localizes to and is an essential component of the cell division ring [42, 56]. Cells lacking Cdc12p are defective in ring and septum formation such that cytokinesis never takes place. These mutants accumulate as large multinucleate cells [42]. Recent mutational studies have shown that contractile ring assembly is mediated by profilin binding to the Cdc12p FH1 domain, whereas the Cdc12p FH2 domain is required for its processive barbed-end capping activity [57]. The third fission yeast formin, Fus1p, acts at the contact zone between mating pairs and is involved in cell wall degradation, reorganization, and membrane fusion [55]. fus1 null mutant cells block conjugation at a point after cell contact and agglutination.

In the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans, the only formin described so far, SEPA, participates in cytokinesis (septation) and polarized growth (Table 1) [45, 51]. This protein localizes simultaneously to septation sites and hyphal tips [51]. Studies of sepA mutants, which fail to septate and show defects in conidiation (asexual spore production), have demonstrated that SEPA is required for the formation of actin rings at septation sites and maintenance of cell polarity during hyphal growth [45, 51].

Three formins have been described in a second filamentous fungus, Ashybya gossypii: Bnr1p, Bnr2p, and Bni1p [50]. The first two proteins are nonessential as mutants lacking Bnr1p or Bnr2p are indistinguishable from wildtype; however mutants lacking both of these formins are unable to grow (Table 1). Bni1p is required for hyphal tip emergence and elongation, as well as for organization of actin cables and tip-directed transport of secretory vesicles. bni1p null mutants fail to develop hyphae and instead expand to potato-shaped giant cells, which lack actin cables (Fig. 2B) [50].

Dictyostelium Formins

The slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum undergoes a lifecycle composed of very distinct stages [58]. In rich media, the single-celled amoebae undergo cytokinesis very similar to that of other eukaryotic cells. When challenged in poor media, cells aggregate to form fruiting bodies that are composed of spores held above the substrate by stalks. These morphological changes involve directed migration, cell-cell adhesion and cell differentiation, indicating that the Dictyostelium cytoskeleton is subject to dynamic modulation between and during the single cell and multi-cell states. Implicated in this control are ten formin genes present in the Dictyostelium genome (ForA to -J; Table 1) [27, 58, 59]. Expression of ForC, -D, -I and -J increases during the transition from single cell to multicellular stages and during sexual development, whereas expression of ForH (also called dDia2) and ForI displayed a significant increase in fusion competent cells. Only four of these Dictyostelium formins (ForA, ForB, ForC and ForH), however, have been studied in a developmental context. Interestingly, these studies implicate the involvement of particular formin at specific stages of Dictyostelium development [58, 59].

No detectable phenotype was observed in mutants lacking ForA, ForB, or both, whereas ForC is required for the formation of the multicellular stages composed of fruiting bodies and slugs (Fig. 2C) [58]. Co-localization of ForC with F-actin along cell edges suggest that these phenotypes are caused by a failure in coordinated morphological movements and suggest a role for ForC in extracellular adhesion. Mutations in ForH/dDia2, on the other hand, result in cytoskeletal defects at the unicellular stage [59]. Cells lacking forH/dDia2 produce significantly fewer filopodia than wildtype cells and exhibit altered morphology. These mutant cells also migrate quicker and have less contact with the substrate, thereby showing an inverse relationship between ForH/dDia2 expression and motility.

4. Genetic and Developmental Insights from Vertebrates

Metazoan formins segregate into 7 groups: FMN, DIA, DAAM, FHOD, INF, FRL/FMNL, and delfilin (Table 1; Fig. 1). Both mice and humans have at least 15 formins that define the seven groups. Xenopus also have formins representing all seven classes and while their genome sequence is not yet complete, may have up to 15 individual genes.

Formin (FMN) Class

Two formins comprise the FMN class in mice and humans: Formin-1 (Fmn1), the founding member of the formin superfamily, and Formin-2 (Fmn2). The `formin' name was originally derived from studies of a transgene insertion in the mouse limb deformity locus (ld) that resulted in kidney and limb abnormalities in the developing embryo. The proteins predicted from the multiple transcripts in the affected locus were named `formins' because of their apparent role in the formation of the limbs and kidneys [60, 61]. Knockout of specific Fmn1 isoforms by gene targeting resulted in partial renal developmental defects, but limb defects were not observed [62, 63]. Since these knockouts did not fully reproduce the ld phenotype, it was suggested that disruption of a nearby limb patterning gene, Gremlin, was responsible for the ld defects [64, 65]. Indeed, a mutant harboring a frameshift in the FH2 domain of Fmn1, which disrupts FH2 function but leaves a global control region important for Gremlin expression intact, was later shown to have no effect on mouse embryonic development, whereas null mutations of Gremlin recapitulate the ld defects [66, 67]. These studies suggest that the ld phenotypes are caused not by loss of Fmn1 protein, but by loss of a region essential for Gremlin expression. A study examining deletion of the Fmn1 gene supports this hypothesis, and suggests that the renal phenotypes reported in the isoform-specific Fmn1 knockout studies above may not be a loss-of-function phenotype, but are rather due to a dominant negative effect [68]. The recent creation of a knock-in mouse containing an enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) fused to Fmn1-Isoform IV has provided new insight into the cellular function of Fmn1 [69]. In primary cells derived from these mice, EGFP-Fmn1-Isoform IV localizes to microtubules and throughout the cytoplasm, but not significantly to adherens junctions. This was an unexpected result as a previous study examining Fmn1 localization by immunofluorescence had identified Fmn1 as an α-catenin binding partner in mouse skin cells, and proposed a role for Fmn1 in adherens junctions and actin filament assembly [37]. Work with Fmn1-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts has also highlighted a possible role for Fmn1 in cell protrusion and focal adhesion formation [69]. Additional studies will be required to reconcile these observations and establish the role of Fmn1 in mice. In humans, Fmn1 has been suggested, but subsequently excluded, as a candidate gene for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2 or LGMD2 [70]. Human Fmn1 is currently not implicated in any other diseases.

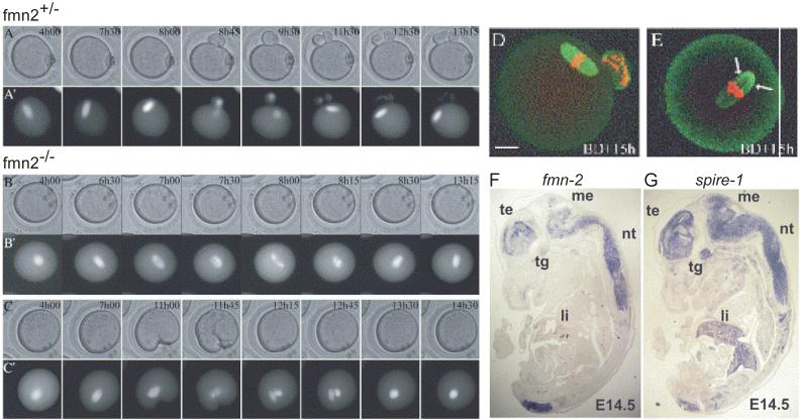

Formin-2 (Fmn2) loss of function studies in mice show that it is required for proper migration of the meiotic spindle and cytokinesis during oocyte development [71, 72]. Fmn2 deficiency causes hypofertility in female mice, resulting from failure of the oocyte to correctly position the meiotic spindle, extrude polar bodies, and complete cytokinesis (Fig. 3). Studies have also shown that Fmn2 is essential specifically for actin filament-dependent processes during meiosis and cytokinesis, such as spindle migration and maintenance of the cytokinetic furrow, but not for actin independent processes, such as spindle formation and cytokinetic furrow formation [71]. This specificity is consistent with a model of Fmn2-mediated actin nucleation of filaments during microfilament driven processes. Similarities in the expression pattern and sequence between the mouse and human homologs of Fmn2 have led researchers to begin examining Fmn mutations as a possible cause in women with unexplained infertility [73, 74].

Fig. 3. Formin-2 is required for proper spindle migration, polar body extrusion, and cytokinesis during meiosis in mouse oocytes.

(A-C) Time-lapse microscopy of phase contrast control fmn2+/- (A) and fmn2-/- (B, C) oocytes show defects in polar body extrusion and cytokinesis in the mutant oocytes. In oocytes injected with tubulin-GFP RNA, which allows visualization of the meiotic spindle, anaphase can be seen taking place in both control (A') and mutant (B', C') oocytes. Figure adapted and reprinted from Dumont et al. (2007) Developmental Biology 301:254-265 [71], with permission from Elsevier. (D-E) In fmn2 mutant oocytes, however, the spindle fails to migrate to the cortex and remains centrally located. Chromosomes that initially separated realign at the metaphase plate. Control oocytes (D) fixed and immunostained (microtubules in green; chromosomes in red) during metaphase II arrest show a barrel-shaped metaphase II spindle close to the cortex, with a haploid number of chromosomes. fmn2-/- oocytes (E) display a mis-localized, slightly longer spindle with double the DNA content. Non-aligned chromosomes can also be observed at spindle poles (arrows in E). Times after GVBD (Germinal Vesicle Breakdown) are given in the upper right corner. Figure adapted and reprinted from Dumont et al. (2007) Developmental Biology 301:254-265 [71], with permission from Elsevier.

(F-G) Overlapping expression patterns of fmn-2 (F) and spir-1 (G) in 14.5 day mouse embryos. In situ hybridizations with antisense RNA probes on sagittal sections from mouse embryos, with the telencephalon (te), mesencephalon (me), the neural tube (nt) and the trigeminal ganglion (tg) as labeled. fmn-2 and spir-1 show expression in all these structures, whereas spir-1 expression is also found in the liver (li). Figure adapted and reprinted from Schumacher et al. (2004) Gene Expression Patterns 4:249-255 [187], with permission from Elsevier.

Diaphanous (DIA) Class

Thus far, much of the work on the Diaphanous class of formins has been focused on their mechanisms of de novo actin nucleation and control of actin dynamics. The mammalian homologs of Drosophila Diaphanous (mDia) have been well described in cell culture studies, and shown to be downstream effectors of Rho GTPases, functioning in cell polarity, actin stress-fiber formation, focal adhesion formation, and cell migration [5, 29, 75-81]. Dia proteins also have profound affects on microtubule dynamics and stability: they localize to and stabilize microtubules at the leading edge of motile cells, suggesting a possible role as coordinators of the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons [32, 79, 82-86] (also see [13] in this special issue). How these functions relate to the developing organism are less well described, but genetic studies of Diaphanous in vertebrates are beginning to shed light on this question. In vertebrate models examined so far, Diaphanous mutants display varied but specific phenotypes. In mice, three formins of the DIA class have been discovered: mDia1, mDia2 and mDia3.

Several studies of mDia1 knockout mice reported defects in the development and function of various hematopoietic cell lineages [87-89]. In one study, targeted deletion of the DRF1 gene, which encodes mDia1, resulted in viable and morphologically normal mice at birth [88]. As these mDia1 deficient mice aged, however, they developed various maladies including dermatoses, splenomegaly, and myelodysplasia, caused by abnormal expansion of myeloid and erythroid precursor cells. The collection of myeloproliferative defects observed resemble those commonly found in human MPS (myeloproliferative syndromes) and MDS (myelodysplastic syndromes), two preleukemic disorders that can potentially transform to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) [90]. mDia1 might thus act as a tumor suppressor in mice, required for maintaining proper myeloid proliferation and function. One possible mechanism of mDia1 regulation of myeloid homeostasis is through activation of the serum response factor (SRF) through actin reorganization [91, 92]. Indeed, a recent study has shown that haploinsufficiency of EGR1, a downstream target of the SRF pathway [93], also contributes to MDS and AML development [94]. Loss of mDia1 in mice might therefore reduce SRF activation of Egr-1 expression, leading to the myeloproliferative defects observed.

Two other studies of mDia1 knockout mice observed defects in T cell development and function [87, 89]. mDia1 removal resulted in a reduction of T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes, suggesting that mDia1 is important for T cell maturation and migration from the thymus to these secondary lymphoid tissues. In vitro and in vivo analyses of T cells from these knockout mice showed that both migration and adherence to substrate are impaired, while receptor or integrin expression remained unaffected. These mDia1-deficient T cells were also less responsive to chemotactic and proliferative signals, failing to accumulate F-actin at synapses following stimulation. The defects observed in T cells of mDia1 knockout mice are very similar to those observed in T cells from WASp mutant mice, raising the possibility of crosstalk between formins and Arp2/3 actin nucleators in the regulation of immune cells [4, 95, 96]. Interestingly, WASp is degraded by a ubiquitin-proteosome pathway in mDia1-deficient T cells [89]. Ectopic expression of WASp does not rescue the T cell defects observed, indicating the T cell phenotypes can be solely attributed to loss of mDia1. Nevertheless, this finding highlights the close relationship between formins and other actin nucleators that is consistent with current studies in cultured cells [97], and emphasizes the need to investigate how they are coordinated in the cell to regulate actin and/or cytoskeletal dynamics.

The viability of the mDia1 knockout mice is somewhat puzzling, as mDia1 has been found expressed in a variety of mammalian tissues and organs including smooth muscle tissue, testis, and brain [98, 99]; localizes to the mitotic spindle [100], cell junctions [101] and membrane ruffles [78] in cultured cells; inhibits vascular permeability to prevent leakage in human endothelial cells [102]; and is expected to have essential roles in cytoskeletal remodeling. Redundancy of the three isoforms, mDia1, mDia2, and mDia3, is the most likely explanation, though one study suggests that mDia1 may be the only DIA class protein present in some cells, such as the T cells described above [89]. mDia2 and mDia3 mutants have not yet been described in mice, but studies with cultured mammalian cells have demonstrated several functions for mDia2, including actin filament bundling [103], cell protrusion formation and regulation [104-107], focal adhesion dynamics [108], microtubule stabilization [86], contractile ring regulation during cytokinesis [109], erythroid cell enucleation [110], endosome trafficking [111], and for mDia3, microtubule attachment to kinetochores [112].

Two DIA class mutations have been discovered and described in humans. A mutation found in DIAPH1, the human homolog of mDia1, has been associated with non-syndromic deafness DFNA1, and is thought to arise from cochlea hair cell sensitivity as a result of impaired actin cytoskeleton maintenance [113]. Mutation in the gene encoding DIAPH2, the human homolog of mDia3, has been linked to premature ovarian failure [114]. The exact mechanisms of how these mutations lead to the described phenotypes are not yet known, and continued work in mouse and other vertebrate models will be crucial for understanding the pathology of these and other formin-related diseases in humans (see accompanying review in this special issue [8]).

Studies in other vertebrates systems have provided additional insight in the role of DIA class formins in development. During vertebrate gastrulation, major tissue movements are coordinated to reshape the embryo from a spherical form to an elongated form. One set of movements, convergent extension, involves the narrowing of the medio-lateral axis (convergence), and elongation and intercalation of cells along the anterior-posterior axis (extension) to lengthen the body plan [115, 116]. Control of cell polarity is essential for this process, as sheets of cells undergo cytoskeletal rearrangements along a bipolar axis parallel to the plane of the sheet. This polarity, perpendicular to the apical-basal axis of the cells, is referred to as planar cell polarity (PCP), and requires signaling through the non-canonical Wnt/Fz pathway, which includes Frizzled (Fz, a seven-pass transmembrane receptor) and Dishevelled (Dsh/Dvl, cytoplasmic protein downstream of Fz) as key components in a cascade leading to Rho family GTPase activation and cytoskeletal rearrangement [115, 117-122]. Though no Dia mutants have been described in zebrafish so far, examination of the effects of Rho knockdown in zebrafish have implicated a role for Dia in convergent extension. RhoA is known to be downstream of Wnt/Fz signaling in PCP establishment [123]. Treatment of zebrafish embryos with morpholinos against RhoA disrupts cell movement and cytoskeletal remodeling during gastrulation and tail formation, resulting in a shorter anterior-posterior body axis, shorter, broader somites and notochord, and improper tail protrusion [124]. These defects, which are also similar to those found in PCP/Wnt mutants, are rescued by ectopic expression of Dia, indicating a downstream role for the formin in the planar cell polarity pathway governing convergent extension movements [124]. Dia-mediated orientation and stabilization of microtubules, and Dia-mediated generation and alignment of actin bundles are possible mechanisms through which Dia fulfills its role in convergent extension [124].

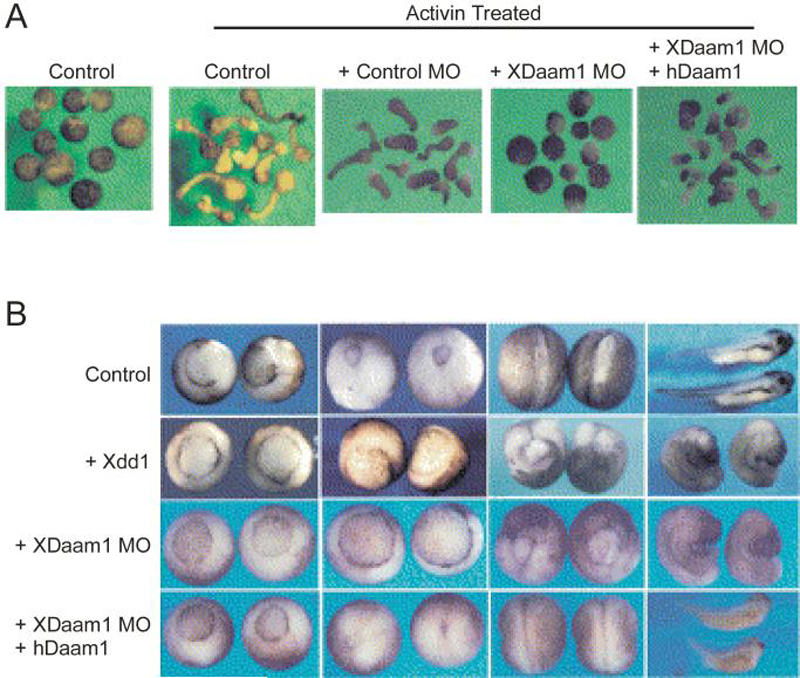

Dishevelled Associated Activator Of Morphogenesis (Daam) Class

The DAAM class of formins was originally discovered in a yeast two-hybrid screen for proteins interacting with the PDZ domain of the Wnt signaling protein Dishevelled [125]. Two DAAM class formins, Daam1 and Daam2, are known to exist in vertebrates. The most extensive analysis of their function in development comes from studies in Xenopus, where Daam1 was identified and shown to be essential for non-canonical Wnt/Fz signaling as an activator of Rho [125]. Morpholino knockdown of Daam1 in Xenopus inhibits elongation in activin-treated embryo explants, causing gastrulation defects in the embryos (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the gastrulation defects in these embryos resembled the defects caused by treatment with dominant negative Dsh, a key signaling component of the non-canonical Wnt/Fz pathway [126, 127], providing evidence for a role for Daam1 in Wnt/PCP signaling. Simultaneous knockdown of Daam1 and profilin exacerbated these defects, leading to the proposal that Daam1-profilin interactions mediate the actin cytoskeleton reorganization required for gastrulation [128]. Daam1 function appears to be specific to the non-canonical Wnt/Fz pathway, as Wnt/β-catenin targets are unaffected by ectopic expression of Daam1 [125]. Together the results suggests a model in which Wnt activation of the Frizzled receptor signals Dsh to translocate to the plasma membrane, forming a Dsh-Daam1-Rho complex. There, Daam1 recruits Rho GEFs to activate Rho and effect cytoskeletal remodeling to polarize the cell.

Fig. 4. Daam1 Regulates Xenopus Gastrulation.

(A) In Xenopus animal pole explants, which represent dorsal tissue, control samples treated with activin undergo gastrulation-like elongation. This elongation is inhibited when XDaam1 protein synthesis is blocked by injection with an XDaam1 morpholino, but not with a control morpholino. Co-injection with RNA encoding a human Daam1 protein, which is resistant to MO interference, prevents this inhibition.

(B) Xenopus embryos dorsally injected with XDaam1 MO also show inhibition of gastrulation, with defects ranging from incomplete blastopore closure, exposure of endoderm cells, a shortened body axis, and microcephaly. Co-injection with human Daam1 RNA alleviates these defects. The phenotypes observed are similar to those in embryos injected with dominant negative Dishevelled (Xdd1), evidence that Daam1 plays a role in Wnt PCP signaling during gastrulation.

Figures adapted and reprinted from Habas et al. (2001) Cell 107:843-854 [125], with permission from Elsevier.

Recent studies examining the mechanism of Daam1 activation have provided insight into how Daam1 and other DRFs such as Dia may be regulated to perform multiple functions. As described above, Daam1 is upstream of Rho, in contrast to other DRFs such as Dia, in which Rho is thought to activate the DRF by relieving auto-inhibition [33]. Similar to Dia and other DRFs, Daam1 is auto-inhibited by a DID/DAD interaction [125]. One study has found that this auto-inhibition is relieved by Dsh/Dvl interaction, rather than Rho GTPase binding, allowing Daam1 to induce Rho activation in the PCP pathway [129]. On the other hand, a different study has found that Rho can relieve the DID/DAD-mediated inhibition of Daam1 actin filament assembly, suggesting that Rho may indeed be upstream of Daam1 [130]. This latter result is supported by genetic studies of Drosophila DAAM [131], which identified a role for DAAM in tracheal development but not in planar cell polarity (see fly section below). Together, these results are consistent with the idea that vertebrate Daam1 has dual roles, functioning as both an actin nucleator and PCP signaling intermediate. Rho appears to promote Daam1 actin-nucleation activity, whereas Dsh appears to induce Daam1 activation of Rho in the PCP pathway. Indeed, this model is supported by a study in zebrafish examining Daam1 regulation of notochord convergent extension [132]. During zebrafish development, notochord cells must modulate their adhesive to allow the movements required for migration and elongation. In addition to PCP signaling, multiple signaling cascades are required for gastrulation, including the Eph/Ephrin pathway, which regulates cell migration and adhesion [133]. Daam1 has been shown to complex with EphB and Disheveled 2 in notochord cells, resulting in dynamin-dependent endocytic removal of EphB, with a concomitant change in the adhesion properties of the cells [132]. Next, Daam1 changes its subcellular localization to associate with F-actin bundles at the cell cortex, thereby promoting cell extension and elongation of the notochord cells [132]. Daam1-mediated nucleation of actin filaments, activated by Rho, may contribute to filament assembly at this step; a positive feedback loop involving Daam1 activation of Rho and Rho activation of Daam1 to further promote actin assembly, may also be triggered as well. The exact mechanisms of how the bipartite functions of Daam are regulated or switched, and whether or not they are mutually exclusive, are not known, but will be essential for our ultimate understanding of how Daam1 regulates development.

Importantly, Higashi et al. have addressed a lingering question in the mechanism of DRF auto-inhibition relief in their study of Daam1 and Dia activation [130]. Active Rho has been demonstrated to relieve Dia auto-inhibition in vitro, but at concentrations much higher than that found under physiological conditions [33]. It has been proposed that other factors are necessary to relieve DRF auto-inhibition in vivo, and Higashi et al. provide evidence for this view by demonstrating that addition of cytosolic extracts allows relief of auto-inhibition at much lower concentrations of Rho.

The various functions of Daam1 may be conserved across vertebrate species, as expression studies in mouse and Xenopus [134] show identical patterns of Daam1 and Daam2 expression that correlate with Wnt-signaling dependent tissues. Studies in chick [135] show similar patterns in developing nervous tissues. The molecular mechanism(s) of how Daam regulates the development of these tissues is of great interest and will likely be aided by the recently solved crystal structures of the Daam FH2 domain [136, 137].

5. Genetic and Developmental Insights from the fly and worm model genetic systems

The roles of formins in an organismal context are perhaps best characterized to date in genetic models systems where there is less redundancy in general and where genetic tools have aided greatly in the elucidation of their biological functions. Drosophila melanogaster have six formins representing six of the seven mammalian-defined formin classes, whereas C. elegans have six formins representing four of the seven classes (Table1; Fig. 1).

Loss-of-function phenotypes associated with Drosophila diaphanous (dia; CG1768) and cappuccino (capu; CG3399), and to a lesser extent Dishevelled Associated Activator of Morphogenesis (DAAM; CG14622) and formin3 (form3; CG33556), representing the DIA, FMN, DAAM, and INF classes of formins, respectively, have been described to date [131, 138-145]. Two additional fly formins, CG6807/CG32138 and CG5797/CG32030, representing the FRL and FHOD classes of formins, respectively, have not yet been examined in a developmental context. Only one of the six predicted C. elegans formin genes, cyk-1, the DIA class representative, has been examined in a developmental context (Fig. 1).

C. Elegans Formins

Cyk-1, the C. elegans DIA class representative, is required for cellularization and cytokinesis (Fig. 5A) [146, 147]. This requirement occurs early in development, as Cyk-1 is required to form and organize membrane invaginations to separate germline nuclei; hermaphrodites possessing strong cyk-1 mutations cannot produce oocytes as a result of the defective cellularization. Weaker cyk-1 alleles result in animals that produce embryos, however following fertilization these mutant embryos cannot extrude polar bodies during meiosis or form proper pseudocleavage furrows and fail to divide. These embryos undergo many rounds of mitosis and eventually express markers of differentiated cell types, but do not undergo cytokinesis, indicating that Cyk-1 is necessary to assemble or allow for proper function of contractile rings.

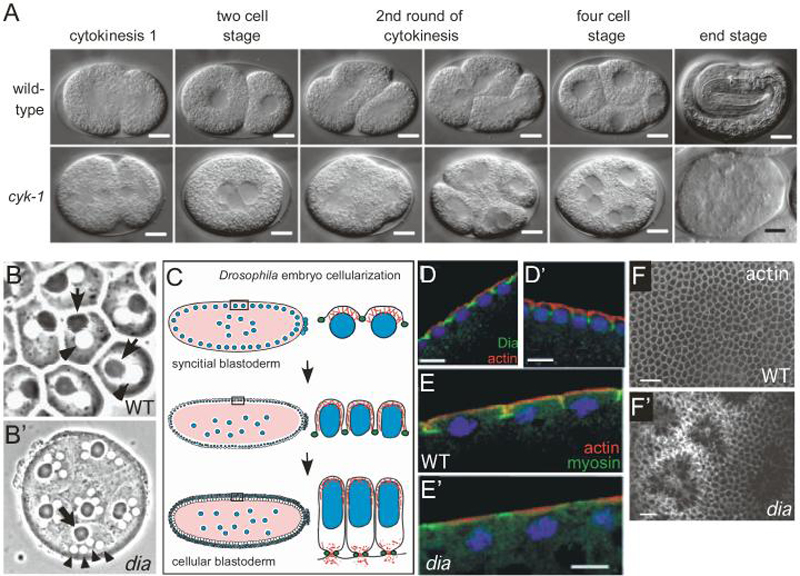

Fig. 5. The DIA family of proteins control cytokinesis and metaphase furrow formation in worms and flies.

(A) cyk-1 mutant C. elegans embryos do not complete cytokinesis. Nuclei still undergo division, resulting in a multinucleate single cell at the end stage. Figure adapted from Swan et al. (1998) Journal of Cell Science 111:2017-2027 [147], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

(B-B') Dia is required zygotically for cytokinesis during spermatogenesis in Drosophila. A cytokinesis defect of a weak dia allele manifests itself in the male germline. In wildtype (B), each spermatid consists of a single nucleus (arrowhead) and a single dark nebenkern (arrow). In dia mutants (B'), multiple nuclei associate with one nebenkern, indicative of a cytokinesis defect. Figure adapted from Castrillon and Wasserman (1994) Development 120:3367-3377 [139], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

(C) Schematic of Dia function in the Drosophila syncitial and cellular blastoderm embryo, where it functions to extend the plasma membrane into metaphase furrows to separate dividing nuclei (blue) through the coordinated regulation of actin (red) and myosin (green). Dia expression overlaps that of myosin.

(D-D') Dia is localized between nuclei during interphase (D) as visualized with an anti-Diaphanous antibody (Dia in green; actin in red; DNA in blue). At prophase (D') Dia localizes to the metaphase cleavage furrows that extend between nuclei. Figure adapted from Afshar et al. (2000) Development 127:1887-1897 [138], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

(E-E') Loss of maternal dia (via germline clones) does not produce the actin (red) structures associated with metaphase cleavage furrows. MyosinII staining (green) is irregular and does not extend downward into the embryo at prophase. Figure adapted from Afshar et al. (2000) Development 127:1887-1897 [138], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

(F-F') Drosophila dia is later required for cellularization. After 13 syncitial cycles, the Drosophila embryo begins to cellularize. Tangential section of blastoderm embryo derived from dia germline clones stained for actin showing an irregular starburst pattern at the cortex. Figure adapted from Afshar et al. (2000) Development 127:1887-1897 [138], and reproduced with permission of the Company of Biologists.

A recently described worm Zn-finger/FH2-domain protein, Fozi-1, has been shown to control transcriptional regulation of muscle cell fate in the postembryonic mesoderm and neuronal symmetry [148, 149]. The FH2 domain of Fozi-1 is unique in that, while it is related to other formin FH2 domains and has homodimerization capability, it has lost the ability to polymerize actin. It is possible that at one time, this protein may have had actin polymerization activity and functioned as a protein with bipartite function, as both an actin nucleation factor and a transcription factor. The non-actin nucleating role of this protein highlights the fact that formin proteins likely have non-canonical roles within the cell.

Drosophila Formins

Mutational analysis of the single fly DIA class formin, diaphanous (dia), provided the first look historically into formin function in the context of a multicellular organism. Dia was shown to be a principle regulator of mitotic and meiotic cytokinesis in both the germline and soma during oogenesis and spermatogenesis (Fig. 5B; Table 1). Different dia allele combinations result in male and/or female sterility with the progeny of these mutants exhibiting phenotypes consistent with failed cytokinesis: multinucleate spermatids, binucleate adult follicle cells, and polyploid larval neuroblasts [139]. dia mutant spermatids have large meiotic spindles, defects in their interzonal microtubules, and an absent actomyosin contractile ring, structures required for proper cytokinesis [139, 141, 150, 151]. Zygotically null dia animals die at the larval to pupal transition as a result of defective cytokinesis leading to the absence of imaginal discs, the epithelial infoldings in the larvae that develop into adult outer body and appendages [139].

The initial stages of fly embryonic development occur in a syncitium: the somatic nuclei divide synchronously within a common cytoplasm for fourteen replicative cycles, at which point cellularization occurs (cf. [152]). Cellularization involves the growth and extension of plasma membrane between the nuclei toward the interior of the embryo to yield a monolayer of cells (the cellular blastoderm embryo; Fig. 5C). Similar to the cytokinetic contractile ring, the cleavage furrows that form to separate the blastoderm nuclei during cellularization accumulate high levels of F-actin and myosin-II. There is a significant maternal Dia contribution to the early fly embryo. Removal of this maternal Dia contribution revealed a role for dia in other actin-mediated events in the syncitial blastoderm embryo, including metaphase (pseudocleavage) furrow formation, cellularization, and pole cell (fly germ cell) formation (Fig. 5D-F) [138]. dia maternal mutants exhibit aberrant actin filament organization at the metaphase and cellularization furrows and a lack of plasma membrane invagination or actin ring formation resulting in abnormal nuclear size, shape, and/or spacing and eventual cellularization failure [138]. Dia is required for the proper recruitment of contractile ring components, including myosin II, anillin, and septin [138, 153, 154]. Consistent with Dia's roles in these actin-mediated processes, Dia is spatially and temporally localized to sites where the metaphase spindle forms, to the leading edge of cellularization furrows, and to the contractile rings that form basally to pinch off the individual blastoderm cells (Fig. 5D) [138, 155, 156]. Once the cells are formed, Dia is also involved in regulating the contractile forces necessary for the cell shape changes, rearrangements, and tissue foldings associated with embryo gastrulation and morphogenetic movements through its effects on myosin levels and adherens junction stability [156, 157].

In addition to its roles in fly morphogenesis, Dia has been implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial movement/anchorage and hemocyte (fly macrophage equivalent) activity [158, 159]. Mitochondrial movement within cells has been shown to occur along both actin filaments and microtubules, and require actin filaments for cortical anchorage at sites of high ATP use (for review see [160]). In ex vivo cell studies, depletion of Dia using RNA interference (RNAi) resulted in increased mitochondrial movement, whereas overexpression of a constitutively active Dia isoform led to decreased mitochondrial mobility [158]. This effect of Dia on mitochondrial motility is specific and not due to non-specific organelle trapping in a Dia-induced dense actin mesh, as the movement of other membrane organelles was not affected by either treatment.

The majority of the circulating cellular immune surveillance cells (hemocytes) in Drosophila are functionally equivalent to mammalian professional phagocytes (macrophages/monocytes) [161, 162]. The Rho family of small GTPases have been shown to mediate actin cytoskeletal rearrangements and adhesions necessary for proper hemocyte migration during embryogenesis and in response to wounding [163, 164]. This regulation has been shown to be reciprocal in the case of Rho1 and Rac1 in fly hemocytes, with Dia being required for Rho1 regulation of Rac1 activity: inhibition of Dia activity resulted in disrupted cellular adhesions and increased hemocyte mobility [159]. This function of Dia appears to be conserved: in mammalian cells, mDia1 has been shown to exhibit similar effects on mitochondrial movement and Rho activation of Rac [159, 160].

Consistent with DRF proteins being regulated by Rho GTPases, dia has been shown to interact genetically with Rho1, the fly RhoA homolog, and with the Rho GTPase guanine exchange factors pebble and RhoGEF2 [155-157, 165-168]. Interestingly, dia appears to use different RhoGEFs to carry out its different functions. While pebble is required for cytokinesis, it is not required for any of the membrane invagination events in the syncitial embryo [168, 169]. RhoGEF2, on the other hand, is required along with dia for proper membrane invagination [155, 156, 165, 167].

dia has also been identified in genetic suppressor/enhancer screens as interactors with the proto-oncogenic kinase Abl, the cell cycle regulator cycB, the homeodomain transcription factor cut, and serine/theonine kinase LimK [170-174]. Abl is required in the early embryo to orchestrate dynamic actin organizations required for proper metaphase furrow formation. Reducing the dose of dia enhances the Abl phenotype and has been proposed to shift the balance of actin polymerization occurring at different subcellular sites required for coordinating distinct morphogenetic processes [171]. Increasing maternal cyclin B in the early fly embryo (six cycB) leads to disrupted coordination between the cell cycle machinery and cytoskeletal function. Reducing the dose of dia suppresses the six cycB overexpression phenotype presumably through an effect on actin microfilaments as astral microtubule morphology was not affected [173]. Although genetic interactions have been established in these cases, the molecular mechanisms utilized by Dia in these processes remains to be elucidated.

Vertebrate DAAM class formin proteins are associated with roles in planar cell polarity through non-canonical Wnt/Fz signaling (see previous section; [117, 119, 121, 122, 125, 128, 132, 134]). This property of DAAM class formin proteins does not appear to be conserved in DAAM, the fly DAAM class formin. Genetic analysis of DAAM loss-of-function and gain-of-function clones in Drosophila wing or eyes (fly model tissues for PCP) indicated that DAAM is not required for PCP signaling, although a redundant role could not be ruled out [131]. Consistent with this, DAAM did not exhibit genetic interaction with dishevelled, a gene involved in PCP, whose human homolog, Dv1, binds human DAAM [125]. Loss of function mutants for DAAM and formin3 (form3), the fly INF class representative, exhibit embryonic lethality and are required for proper tracheal development [131, 144]. The tracheal system in Drosophila is an air-filled highly branched tubular network that spans the organism transporting oxygen to internal tissues (for review see [175]). The cell shape changes, rearrangements, migrations and fusions underlying tracheal tube morphogenesis have been shown to involve highly coordinated changes in the cytoskeleton [175]. Tracheal tubes collapse and are discontinuous in DAAM mutants, whereas Form3 is required for the formation of an F-actin track that mediates tracheal cell fusion. Whereas many formins are ubiquitously expressed, the expression patterns reported for both DAAM and Form3 are more temporally and spatially restricted: i.e., Form3 expression is predominantly in tracheal cells [144]. The requirement for fly DAAM and Form3 in other tissues has not yet been examined, however, their more restricted expression may indicate that their developmental roles are more specific as well.

DAAM has been shown to interact genetically with Rho1, the fly RhoA homolog, and with Src42A and Tec29, two Src family non-receptor tyrosine kinases [131]. Src kinases have also been linked to formin function and Rho GTPases in other systems: DAAM1 interacts with RhoA, Cdc42, and Src to regulate actin cytoskeletal dynamics and cell morphogenesis [176]; mDia1 and mDia2 require Src activity for cytoskeletal remodeling and SRF activation [77, 91]; and human DIA2C regulation of endosome dynamics with RhoD requires Src activation [177]. The existing genetic data suggests that Rho1 acts upstream of DAAM, and consistent with its role as a DRF, is regulated by auto-inhibition that can be relieved by the binding of Rho GTPases [131].

6. Drosophila Cappuccino and Spire: Interactions of formins with other actin nucleation factors

Drosophila contains a single FMN family member, Cappuccino (Capu). Studies on Capu highlight the fact that it possesses biochemical properties in addition to actin nucleation, and demonstrate the complexity of formin interactions with other classes of actin nucleation factors in the regulation of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. capu was initially identified along with the WH2 domain-encoding gene spire as maternally required loci in a genetic screen for female sterile mutations affecting patterning during both oogenesis and embryogenesis [140, 143, 178]. capu and spire were noteworthy in that they were the first loci described to affect patterning of both the anterior-posterior (A/P) and dorsal-ventral (D/V) axes of the fly egg and early embryo [143]. Both capu and spire mutant females produce eggs with polarity and eggshell defects, and embryos that exhibit abnormal cellularization, multinucleate cells, lack polar granules and pole cells (fly germ cells), and display abnormal abdominal segmentation (Fig. 6) [140, 143, 178].

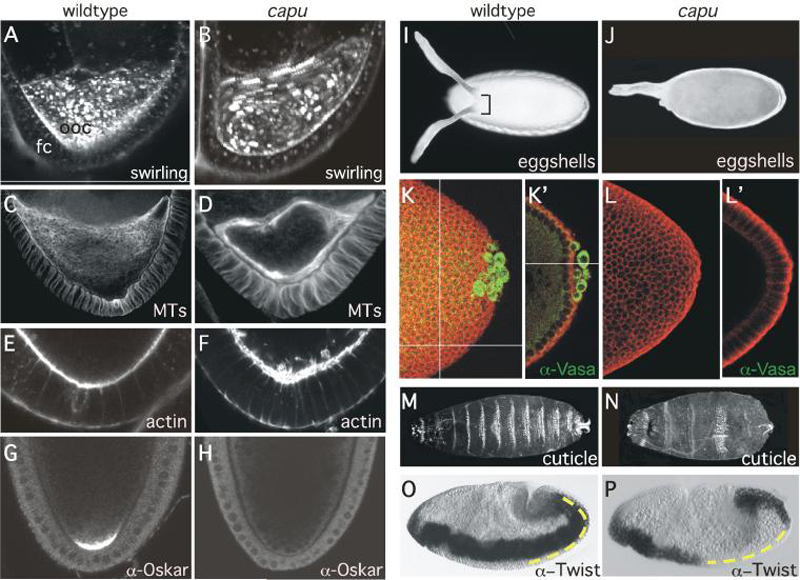

Fig. 6. Phenotypes associated with capu null mutants.

(A-B) Drosophila oocytes undergo ooplasmic streaming at stage 10. capu oocytes undergo premature ooplasmic streaming beginning at stage 7. 5-frame confocal temporal projections of confocal time-lapse movies of wildtype (A) and capu (B) mutant stage 7 oocytes stained with trypan blue to visualize dynamic yolk granule movement. Granules appear as discrete spots of fluorescence in the still images. Spiral patterns of fluorescence in the temporal projections indicate coordinated yolk granule movement generated by ooplasmic streaming. FC indicates follicle cells and OOC denotes the oocyte. Anterior is up.

(C-D) Confocal micrographs of stage 7 oocytes from wildtype (C) and capu (D) females stained with !-tubulin to visualize dynamic microtubules (MTs). Note that the anterior to posterior gradient of microtubules seen in wildtype is lost in capu mutants. Capu mutant oocytes display subcortical arrays consistent with microtubule-dependent ooplasmic streaming. Anterior is up.

(E-F) Actin cytoskeleton is disrupted in capu mutant oocytes. Confocal micrographs of stage 7 posterior oocyte cortex from wildtype (E) and capu (F) females stained with phalloidin to visualize actin. Note disorganization of the oocyte cortical actin in capu mutants. Anterior is up.

(G-H) Premature ooplasmic streaming leads to the mis-localization of developmental determinants in capu mutants. Confocal micrographs depicting posterior localization of Oskar protein in stage 10 oocytes from wildtype (G) and capu (H) females. Note the loss of Oskar accumulation at the posterior cortex in capu mutants. Anterior is up.

(I-J) Darkfield photomicrograph of eggshells from wildtype (I) and capu mutant (J) eggs showing dorsal-ventral polarity phenotypes. Note fusion of the dorsal appendages in capu mutants.

(K-L') Mis-localization of developmental determinants such as Oskar in the oocyte leads to lack of pole cells (germ cells) in capu mutant embryos. Confocal photomicrograph projections (K-L) and cross-sections (K'-L') of posterior end of cycle 14 wildtype (K-K') and capu mutant (L-L') embryos double labeled with antibodies to Vasa protein (green) to visualize pole cells (germ cells) and phosphotyrosine (red) to outline cells.

(M-N) Ventral surface of larval cuticles depicting representative examples of wildtype (A) and capu (D) phenotypes. Note the disruption of patterning (fused denticle bands) along the anterior-posterior axis. Anterior is to the left.

(O-P) Nomarski photomicrographs of mesodermal Twist expression in stage 12 wildtype (O) and capu mutant (P) embryos undergoing gastrulation. Dashed yellow line indicates posterior localization of Twist protein crucial for abdominal determination. Anterior is to the left and dorsal is up.

Images courtesy of A. Rosales-Nieves, J. Johndrow, L. Keller, and K. Barry (Parkhurst Lab, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center).

At a specific time and stage in Drosophila oogenesis, the oocyte undergoes a microtubuledependent coordinated movement of the cytoplasm, called ooplasmic streaming, which serves to redistribute various intracellular components/organelles and morphogenetic determinants. Timelapse live-imaging analyses of capu and spire mutant oocytes demonstrated that these oocytes have disrupted cortical actin, abnormal microtubule distributions, and exhibit premature ooplasmic streaming [140, 145, 179]. This premature streaming interferes with normal transport mechanisms within the oocyte required for the localization of early polarity markers resulting in the disruption of oocyte cytoarchitecture and subsequently the axial patterning of the embryo [140, 143, 145, 178-180]. Over the years, capu and spire have been joined at the hip genetically owing to their similar mutant phenotypes and their unusual status of affecting both the A/P and D/V patterning axes. Only recently has it been appreciated that both genes have even more in common as they both encode de novo linear actin nucleation activity and interact with each other genetically and physically [19, 179]. Indeed, progeny from doubly heterozygous capu and spire females display similar phenotypes as those from capu or spire homozygous mutant mothers [140, 143, 145, 178, 179].

How Capu and Spire, as factors encoding actin nucleation activity, regulate the oocyte microtubule reorganization leading to their oogenesis phenotypes is somewhat paradoxical. Four recent studies have converged on two basic models to account for the Capu-Spire interaction and phenotypes observed: (i) cortical actin-microtubule cross-linking and (ii) actin mesh formation [179, 181-183].

(i) Rosales-Nieves and colleagues have proposed that Capu and Spire, independent of their actin nucleation activity, act at the oocyte cortex to regulate cortical polarity and coordinate actin-microtubule cross-talk to time the onset of the microtubule-dependent cytoplasmic streaming in the oocyte [179]. In support of this model, Capu, Spire, and the Rho1 small GTPase are preferentially localized to the oocyte cortex, and Capu and Spire exhibit novel actin bundling, microtubule bundling, and actin-microtubule cross-linking activities that are regulated by interaction with each other and Rho1 [179]. Further support for this model comes from a recent study demonstrating that Chickadee, encoding fly profilin, is required for the formation of cortical actin bundles in the oocyte, and that Capu and Spire anchor the minus ends of microtubules to a scaffold made from these cortical actin bundles [183]. These results do not downplay the importance of Capu or Spire actin nucleation activity, but rather suggest dual or multifaceted biochemical roles for these proteins in regulating developmental processes. Other formins have also been shown to display a wide variety of non-actin nucleating roles such as actin severing/depolymerization, microtubule stabilization, signaling, and transcriptional regulation [40, 103, 179, 184, 185] (also see [11] in this special issue). While null capu alleles result in female sterility, Capu is expressed in complex spatial and temporal patterns in the embryo, suggesting that Capu may be redundant to other formins (or other actin nucleation factors) in the embryo. In contrast to capu, spire is a complex genetic locus and the spire alleles reported to date are not genetically or molecularly null. Indeed, stronger spire alleles exhibit zygotic lethality indicating additional developmental processes in which its activities are essential (M.T. Abreu-Blanco and SMP, unpublished observation). The interaction between Capu and Spire suggests that other formins may carry out their function in concert with other nucleating proteins, either directly in a complex or indirectly in a local actin dynamics rich environment.

(ii) Dahlgaard and colleagues have proposed that Capu and Spire are required to organize an isotropic mesh of actin filaments in the oocyte cytoplasm that suppresses motility of the plus-end directed microtubule motor protein kinesin, which in turn is required for ooplasmic streaming [181]. Consistent with this model, Capu and Spire construct an actin mesh that is present prior to the onset of ooplasmic streaming, at which time it disappears, allowing maximal kinesin-based movement to provide the force to reorganize microtubules into subcortical arrangements suited for cytoplasmic streaming [181]. In addition, recent in vitro biochemical data suggests that Spire antagonizes Capu nucleation activity while Capu enhances Spire nucleation activity [182], but how this corresponds to the observed developmental phenotypes in vivo remains to be determined. The exact role of kinesin in this process is not yet clear as a subsequent study showed kinesin is not completely required for this reorganization, suggesting Capu and Spire may not act as indirect kinesin regulators, but as direct modulators of the microtubule cytoskeleton [183]. One possibility may be that Capu and Spire are bundling and crosslinking microtubules to profilin-dependent F-actin at the oocyte cortex, as has been demonstrated in vitro [183, 186]. Ultimately, details of how Capu's and Spire's various biochemical activities converge to regulate development will require dissecting the relative importance of their actin nucleation properties with their other molecular properties, such as microtubule bundling, in an organismal context using genetic and developmental studies of null, conditional, and double/triple mutant combinations.

The genetic and physical interactions of Capu and Spire also provide a clear example of cross-talk between two different classes of actin nucleators. Interestingly, interactions between actin nucleators may be conserved through evolution, as evidenced by a phylogenetic analysis showing the presence of Capu orthologs in all organisms that contain Spire homologs and vice versa [6, 182] and the similarity of mammalian Fmn-2 and Spir-1 expression patterns (Fig. 3F-G) [187]. The fact that formins and other actin nucleators such as Spire, Wasp, Scar and Cordon bleu are all involved in related morphogenetic processes, encourages a new direction of study into the interactions among these actin/microtubule remodeling proteins and how they regulate each other to control development.

7. Genetic and Developmental Insights from plants

The Arabidopsis genome is predicted to contain over 20 formin genes that have been divided into two clades, type-I and type-II, that are distinct from the seven metazoan formin families (Fig. 1; also see accompanying review in this special issue, [9]). Currently, developmental roles of only the type-I formins have been examined in any biological context [41, 188]. Mutant analysis has revealed few essential roles for these proteins, most likely due to redundancy within the clades. Arabidopsis Arp2/3 null mutants do not exhibit severe defects (reviewed in [189]), suggesting that formins may be the predominant actin nucleator in plants. Arabidopsis formins have been implicated in such developmental processes such as cytokinesis and cellular projections, indicating the function of formins may be conserved across different organisms, albeit with inherent differences.

While the large number of type-I formins may cooperate to regulate general actin nucleation, analysis of mutant phenotypes reveals roles for specific formins at different developmental times. The formin AtFH5 is expressed in all plant tissues, but null mutant phenotypes only arise during endosperm development, where it controls the timing of cell plate growth to separate nuclei during cytokinesis (Fig. 7) [190]. Furthermore, cyst formation at the posterior of the endosperm is disrupted, a process that involves directional migration of nuclei along cytoskeletal tracks [191]. AtFH8 is implicated in the organization of root hair formation, cellular projections containing arrays of F-actin [192, 193]. Similarly, AFH1 controls pollen tube formation, another actin-based cellular projection [194]. In addition to regulating the formation and maintenance of cellular structures, formins such as AtFH6 may act to regulate growth rate in response to longterm rearrangement of the cytoskeleton by parasites [195].

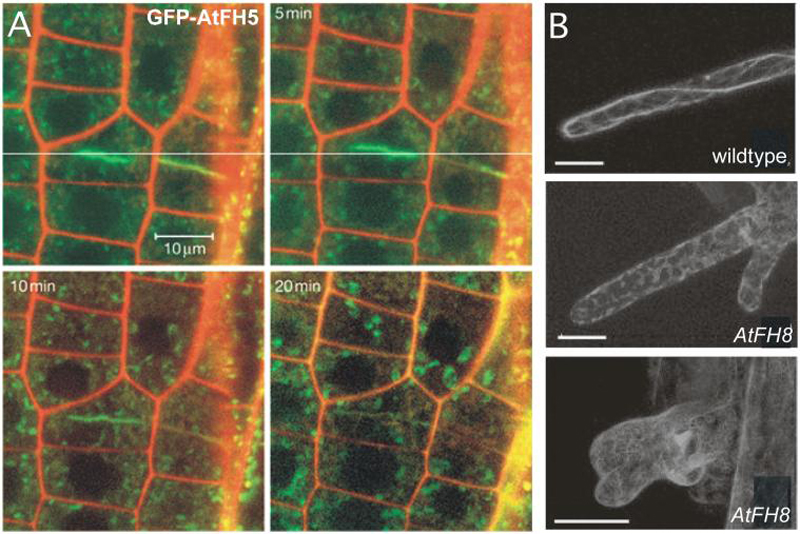

Fig. 7. Plant formins are involved in cytokinesis and cell expansion.

(A) GFP-AtFH5 accumulates at the cell plate during cytokinesis, shown here near the tip of an Arabidopsis root. This accumulation declines after the new cell wall is completed. Figure adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Ingouff et al. (2005) Nature Cell Biology 7:374-380 [190].

(B) Over-expression of AtFH8 disrupts actin filaments in root hairs. An increase in AtFH8 levels leads to a variety of root hair bulge defects, as visualized by GFP-mTalin. Figure adapted and reprinted with permission of the American Society of Plant Physiologists, from Yi et al. (2005) Plant Physiology 138:1071-1082 [193]; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

8. Conclusions/Perspectives: Formin common developmental themes

Genetic studies have so far revealed several common themes among formins in developmental processes. One is that in almost all species studied, at least one formin or class of formins are essential for cell division. Examination of these cell division phenotypes shows that steps requiring F-actin formation, such as cytokinetic furrow contraction and spindle pole migration, appear to be the most disrupted in the various formin mutants. These observations correlate well with a role for actin nucleation by the conserved FH2 domain of formins, and demonstrate an evolutionarily conserved function for formins in development. Another common theme is that many formins appear to exhibit both overlapping, redundant functions and unique, specific functions in each organism. Examples can be found in the fungal formins: formins appear to play separate but complementary roles, thereby exhibiting specificity, and deletion of multiple formins is required for lethality, thereby suggesting redundancy. Another example is the recent discovery in mice that mDia1 knockout results in viability with predominantly hematopoietic defects [87-89]. This finding was quite surprising, considering that disruption of actin nucleation activities might be expected to have global effects on cell structure and morphology. Instead only a specific subset of processes appears to be disturbed, and how such specificity is achieved in this and other examples is of major interest. Studies of formins have identified fairly specific expression patterns among the formins, suggesting that spatial regulation of formins may control where a particular formin exerts its activities. Additionally, formins may be redundant in the most essential functions and less so with specific ones. Ablation of a single formin would therefore selectively affect cells requiring its unique functions, while cells requiring more essential functions are unaffected due to compensation by other formins or, perhaps, by other actin nucleators.

Formins also appear to have unique functions across species, as homologous formins from the same class can sometimes demonstrate different phenotypes across organisms. Though mDia1 knockouts exhibited defects in the immune cells of mice, mutants of the homologous formins in humans and Drosophila are associated with defects in meiotic cell division [87-89, 139, 141, 150, 151]. In vertebrates, the formin Daam1 has been identified as an integral member of the planar cell polarity pathway regulating gastrulation [125, 128, 132], whereas in Drosophila, Daam has no essential role in this pathway, and instead is required for actin cable organization in tracheal development [131]. Differences in expression and regulation patterns across organisms, in protein sequence and structure homology, as well as differences in the types of mutations examined (for example, null mutations versus gain of function mutations). In addition to variations in the FH2 domain among these homologous formins, the disparities exhibited across species may be explained by differences in the non-FH2 regions of the proteins, which likely bestow both unique and similar properties upon each formin [32]. Such variation may also account for the differences observed between formin classes within each organism. Differences in regions responsible for localization, activation, and other forms of regulation will be reflected in the cellular processes in which each formin participates. Likewise, similarities among these regions may result in the conservation of various aspects of formin function and regulation. Drosophila and mammalian Daam, for example, are distinct in that they mediate different morphogenetic processes in their respective organisms, but appear to share domains that mediate auto-inhibition, albeit by difference mechanisms [129, 131].

The presence of additional domains in formins brings into focus another common theme found among the formins, which is the ability to serve functions other than actin nucleation. Much of the attention on formins so far have been centered on their de novo actin nucleation activities and properties, but recent findings have begun to shed some light on other functions mediated by both FH2 and non-FH2 domains of the proteins. Some of these other functions include actin and microtubules bundling (Capu) [179], scaffolding (Daam) [125], transcriptional regulation (Foz-1) [148, 149], and microtubule stabilization [83, 86]. The relative importance of a formin's actin nucleation versus their non-nucleating activities, or how the two relate to each other is not well known, but some details are beginning to surface. Studies examining the interaction between Drosophila Cappuccino and another actin nucleator, Spire, for example, have suggested an interaction between the two that modulates their abilities to bundle microtubules, bundle actin filaments and cross-link actin and microtubules, as well as nucleate actin [179, 182, 186]. Studies of mDia and WASp function in mice also suggest possible crosstalk between linear and branched actin networks as well [87, 89, 196], while studies examining mDia1 and mDia2 function in mammalian cells suggest FH2 domain-mediated microtubule stabilization and actin nucleation activity may be mutually exclusive [83, 86]. The possibility that formins and other actin nucleators can inhibit or enhance one another's activities is intriguing, and further work examining interactions between multiple formins, especially those with similar mutant phenotypes or expression profiles, will be of great value.

Another common theme is that many formins examined to date are required for generating elongated, linear or branched cellular structures, both stable and dynamic. Many mutant phenotypes observed appear to stem from losing the ability to form these structures, resulting in multiple consequences in both development and function. Loss of Bni1p in A. gossypii prevents hyphae formation [50], mis-regulation of AFH1 in plants disrupts pollen tube formation [194], while loss of DAAM disrupts tracheal branches in Drosophila [131]. More dynamic structures, such as filopodia and lamellipodia, are also affected. Removal of mDia1 in mice hinders migratory activity of immune cells [87] and loss of dDia2 in Dictyostelium results in fewer filopodia [59]. Interestingly, over-expression of de-regulated forms of Bni1p or Bnr1p in yeast also results in lethality [50]. This formin over-activity leads to excess actin filament assembly. However, it is not the excess filament assembly, but rather that the excess filaments assembled are of improper composition that leads to the lethality [197]. The relationship between formin mediated formation of dynamic structures versus stable structures, as well as what accessory proteins interact with formins to stabilize these structures, will be important for understanding the web of interactions within and between cells of a developing organism, and accordingly is the subject of many ongoing studies.

9. Remaining Questions and Challenges