Abstract

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) is the major regulator of tissue factor (TF)-induced coagulation. It down regulates coagulation by binding to the TF/fVIIa complex in a fXa dependent manner. It is predominantly produced by microvascular endothelial cells, though it is also found in platelets, monocytes, smooth muscle cells, and plasma. Its physiological importance is demonstrated by the embryonic lethality observed in TFPI knockout mice and by the increase in thrombotic burden that occurs when heterozygous TFPI mice are bred with mice carrying genetic risk factors for thrombotic disease, such as factor V Leiden. Multiple TFPI isoforms, termed TFPIα, TFPIβ, and TFPIδ in humans and TFPIα, TFPIβ, and TFPIγ in mice, have been described, which differ in their domain structure and method for cell surface attachment. A significant functional difference between these isoforms has yet to be described in vivo. Both human and mouse tissues produce, on average, approximately 10 times more TFPIα message when compared to that of TFPIβ. Consistent with this finding, several lines of evidence suggest that TFPIα is the predominant protein isoform in humans. In contrast, recent work from our laboratory demonstrates that TFPIβ is the major protein isoform produced in adult mice, suggesting that TFPI isoform production is translationally regulated.

Keywords: tissue factor pathway inhibitor, blood coagulation, alternative splicing, translational regulation

Blood coagulation is initiated following disruption of intact endothelial surfaces that exposes tissue factor (TF) to FVIIa in flowing blood. The TF/FVIIa complex then activates FIX and FX to initiate the TF dependent pathway of blood coagulation. The primary physiological inhibitor of this pathway is tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). The discovery and characterization of TFPI has a long history, beginning with the discovery by Carson[1] and Sanders etal.,[2] of a plasma protein that inhibits the activity of the TF/FVIIa complex. This work led to the purification and identification of TFPI from conditioned medium of HepG2 cells by Broze and coworkers.[3]

In order to understand the role TFPI plays in disease, it is imperative to understand the role of TF in disease processes. Tissue factor is constitutively expressed by extra-vascular cells surrounding vessel walls and by activated cells within the vasculature.[4–6] Increased TF is present at both intra- and extra-vascular sites in a number of disease processes including infections, inflammation, cancer, and cardiac disease. Additionally, small amounts of circulating TF are present in healthy humans and mice suggesting that a basal low level of coagulation continuously occurs in vivo.[7–9] TFPI down regulates this TF activity limiting the formation of intravascular thrombi.

TFPI Structure

TFPI is a 276 amino acid (~43kDa) multivalent Kunitz-type protease inhibitor encoded on chromosome 2.[10] Full length TFPI (also called TFPIα) contains an acidic amino terminal region, three Kunitz protease inhibitor domains and a basic carboxy-terminal region.[11] The first (K1) and second (K2) Kunitz domains inhibit TF/FVIIa and factor Xa, respectively, resulting in the formation of a quaternary TFPI-TF/FVIIa-FXa complex.[12] An inhibitory function for the third (K3) Kunitz domain has not been identified.

Physiological Activity of TFPI

TFPI deficiency has not been described in humans, and mice lacking TFPI activity have an embryonic lethal phenotype demonstrating that TFPI is essential for embryogenesis. Sixty percent of these TFPI knock-out mice die by day E10.5 with the remainder dying at variable times up to day E17.5.[13] Phenotypically, the mice have yolk sac hemorrhage between days E9.5–11.5, vascular abnormalities in the placenta, hemorrhage within the head, spine and tail, and fibrin deposition in the brain and liver. The embryonic lethality is rescued by breeding TFPI deficiency into mice producing low amounts of TF, conclusively demonstrating that TFPI directly counterbalances TF activity in vivo.[14]

In contrast to TFPI null mice, TFPI heterozygous mice appear normal without evidence of spontaneous thrombosis.[13] However, several studies have demonstrated that heterozygous TFPI deficiency synergizes with other genetic abnormalities to produce thrombotic disease. Heterozygous TFPI deficiency increases the atherosclerotic burden in the carotid and common iliac arteries in mice lacking apolipoprotein E.[15] When TFPI heterozygosity is bred into mice with FV Leiden, the mice die in the perinatal period with large amounts of fibrin deposition in the liver, lung and kidney.[16] Finally, when TFPI heterozygosity is bred into mice with decreased thrombomodulin function the mice have decreased embryonic survival, a generalized prothrombotic state, increased clot size in an in vivo electrolytic injury model, and intravascular fibrin deposition in the liver and in the pia mater vessels of the brain.[17]

Cellular Production of TFPI

TFPI is found in a number of vascular locations. It is predominantly (85%) associated with microvascular endothelial cells.[18;19] Soluble TFPI within human plasma is variably truncated in the C-terminal region and has decreased anticoagulant activity.[20;21] A small amount of TFPI is present on the surface of monocytes[22] and has been detected in the macrophages of atherosclerotic lesions[23] and smooth muscle cells.[24;25] Studies quantifying TFPI in whole blood have found that platelet TFPI accounts for about 8–10% of the total TFPI with plasma accounting for the remainder.[26;27] Interestingly, TFPI is not on the surface of quiescent platelets, but is expressed on the platelet surface following dual stimulation with collagen and thrombin.[27]

Alternatively Spliced Isoforms of TFPI

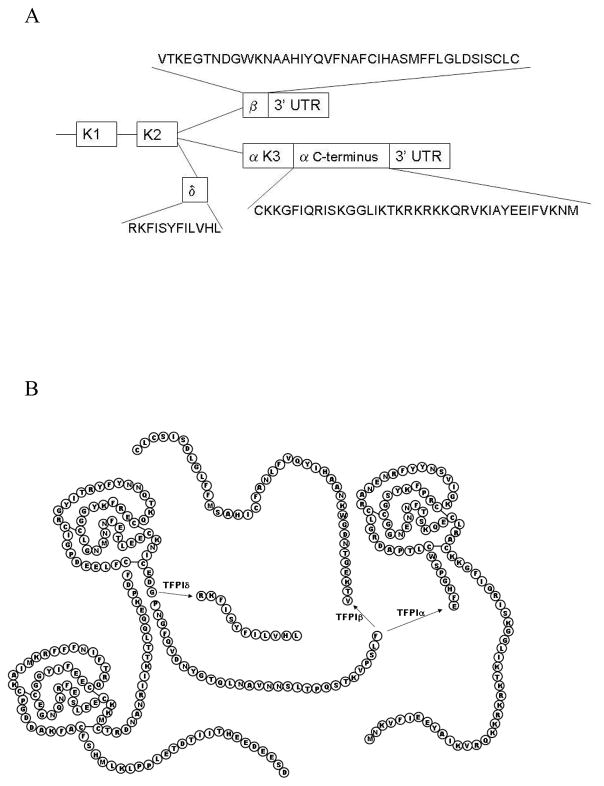

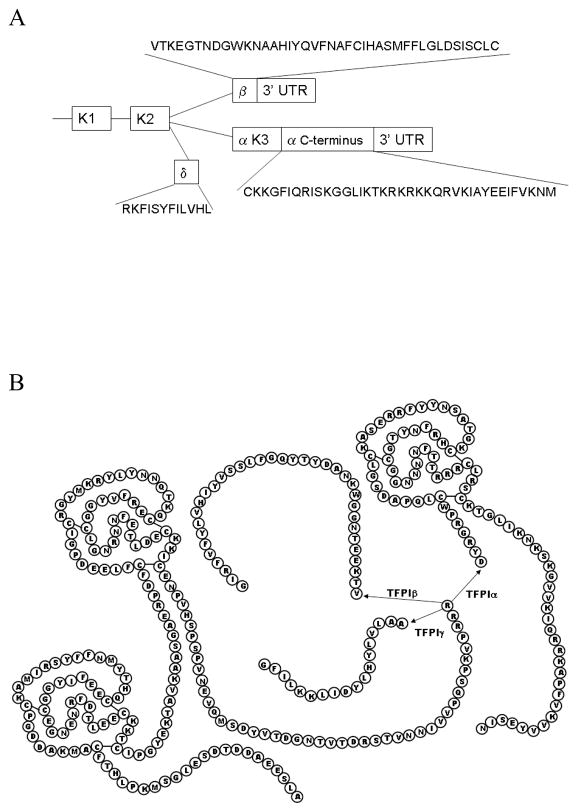

There are several alternatively spliced isoforms of TFPI designated as α, β, and δ and α, β, and γ in the human and mouse, respectively (Figures 1 and 2). These isoforms differ in their domain structure and mechanism for cell surface attachment. All alternatively spliced isoforms identified to date contain K1 and K2 and, therefore, can at least theoretically inhibit TF/FVIIa and FXa.

Figure 1.

(A) Box diagram of the alternatively spliced forms of human TFPI. The amino acid sequence for the C-terminal region of each isoform is indicated. Only the first 12 amino acids of the C-terminal region of TFPIβ are predicted to be in the mature protein. The remainder of the C-terminal region encodes a GPI-anchor attachment sequence and is removed in the endoplasmic reticulum. (B) Diagram of the amino acid sequences of TFPIα, TFPIβ and TFPIδ showing the Kunitz domain structures and common 5′ splice donor site for TFPIα and TFPIβ, while the TFPIδ 5′ splice site is immediately following K2.

Figure 2.

(A) Box diagram of the alternatively spliced forms of mouse TFPI. The amino acid sequence for the C-terminal region of each isoform is indicated. Only the first 8 amino acids of the C-terminal region of TFPIβ are predicted to be in the mature protein. The remainder of the C-terminal region encodes a GPI-anchor attachment sequence and is removed in the endoplasmic reticulum. The coding sequence for the C-terminal region of TFPIγ is located within the 3′UTR of TFPIβ. (B) Diagram of the amino acid sequences of TFPIα, TFPIβ and TFPIγ showing the Kunitz domain structures and common 5′ splice donor site for all three isoforms.

TFPIα

TFPIα is the “full-length” isoform that was originally purified and characterized. It is the only isoform with K3 and the basic C-terminal region. All three Kunitz domains of TFPIα are well conserved from man to zebrafish even though they have not shared a common ancestor for 430Myr.[28] The other alternatively spliced isoforms of TFPI evolved more recently. The evolutionary conservation of K3 and the basic C-terminal region of TFPI suggest that it has an important physiological function. The basic C-terminal region binds to cell surface glycosaminoglycans. Consequently, the human plasma TFPIα concentration increases 2- to 4-fold following heparin infusion.[29;30] However, the major mechanism for the association of TFPIα with cell surfaces is through a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. GPI-anchored TFPIα is not removed by heparin and is present in approximately 10- to 100-fold higher amounts than heparin releasable TFPIα in human placenta.[19;31;32] Since TFPI does not contain a C-terminal GPI-anchor attachment sequence, it has been hypothesized that it indirectly associates with the cell surface by tightly binding to a, as yet unidentified, TFPI binding protein.[19;31;32]

TFPIβ

TFPIβ contains K1 and K2 but lacks K3 and the basic C-terminal region of TFPIα. Instead, it has a different C-terminal region that encodes a GPI anchor attachment sequence.[32;33] Thus, TFPIβ associates with cell surfaces through direct binding to a GPI-anchor. Mature human TFPIβ has 12 C-terminal amino acids not present in TFPIα (Figure 1) while mouse TFPIβ has 8 (Figure 2). TFPIβ sequence has been identified only in mammals, humans, chimpanzee, long tailed macaque, mice and rats and, therefore, represents a more recent evolutionary adaptation than TFPIα.[28] In studies performed using soluble forms of TFPI, K3 and the basic C-terminal region of TFPIα are required for full inhibitory activity in amidolytic assays measuring inhibition of FXa and in TF initiated plasma clotting assays.[34;35] However, studies of a chimera protein in which K1 and K2 are linked to annexin V to create a protein with high affinity for phosphatidylserine containing vesicles found that its anticoagulant activity increased 250-fold when compared to the same protein lacking annexin V.[36] Thus, the relative anticoagulant activities of the TFPI isoforms are greatly altered by association with cell surfaces. Further studies are needed to compare the anticoagulant activity of cell surface associated TFPIα and TFPIβ in order to predict their relative anticoagulant efficacies in vivo.

TFPIγ

TFPIγ contains K1 and K2 and has the same 5′splice acceptor site as TFPIβ. The 3′-splice acceptor site of TFPIγ is found 276 nucleotides downstream of the TFPIβ stop codon within the TFPIβ 3′ UTR. Alternative splicing for TFPIγ produces a C-terminal region with 18 amino acids not present in TFPIα or TFPIβ (Figure 2).[37] This region does not encode a predicted membrane attachment sequence and TFPIγ is secreted when expressed in CHO cells suggesting that it is produced as a soluble protein in vivo.[37] TFPIγ is produced exclusively in mice. Homologous sequence is not present in human, chimpanzee, rhesus monkey, rat, dog, cow or horse suggesting that it is a very recent evolutionary adaptation. TFPIγ mRNA is produced in all adult mouse tissues. TFPIγ protein has not been definitively identified in mouse tissues, but TFPIγ inhibits TF/FVIIa procoagulant activity when expressed in CHO cells.[37] Since TFPIγ is a functional anticoagulant, it may partially explain the resistance of mice to coagulopathy in TF-mediated models of disease.

TFPIδ

TFPIδ sequence is present within the NCBI GenBank database. Other than these sequences, no information regarding TFPIδ has been published to date. TFPIδ sequence encodes the K1 and K2 domains. Alternative splicing occurs immediately following K2 and generates a new C-terminal region containing 12 amino acids (Figure 1). TFPIδ sequence has been found in humans and chimpanzees, NCBI protein reference sequences BAD93103.1 and XP_001161803.1, respectively.

Transcription of Alternatively Spliced Forms of TFPI

Real time PCR studies have shown that production of TFPIα message, when compared to a housekeeping message for RPL-19, is greatest in the placenta, and lowest in the brain in both humans and mice. Other tissues produce intermediate amounts of TFPIα mRNA with relatively large amounts made by the heart and lung.[37] In both humans and mice all tissues produce 4- to 50-fold more TFPIα mRNA than TFPIβ mRNA depending on the tissue examined.[37] These findings are consistent with studies of human endothelial cell lines in which TFPIα mRNA is approximately 10-fold more abundant than TFPIβ mRNA.[38;39]

Translation of Alternatively Spliced Forms of TFPI

Several lines of evidence indicate that TFPIα is the predominant isoform produced by human tissues. These include (i) human placenta produces TFPIα;[19] (ii) human platelets produce exclusively TFPIα;[27] (iii) the transformed human endothelial-like Ea.hy926 cell line produces exclusively TFPIα;[38] and (iv) heparin infusion results in a 2- to 4-fold increase in human plasma TFPI concentration and this heparin-releasable TFPI is exclusively TFPIα.[30] TFPIβ and TFPIδ protein have not been identified within human tissue; however, a comprehensive study of alternatively spliced forms of TFPI produced by human tissues has not been reported. In mice, TFPIα and TFPIβ are temporally expressed at the level of protein production.[28] The placenta produces predominantly TFPIα along with small amounts of TFPIβ while E14.5 embryos produce approximately equal amounts of TFPIα and TFPIβ. In contrast to the apparent expression of TFPIα in adult humans, adult mouse tissues produce almost exclusively TFPIβ. Consistent with their production of TFPIβ, adult mice have a much smaller heparin-releasable pool of TFPI than is present in humans.[28] The evolutionary conservation of TFPIα and its conserved production in mouse placenta and embryonic tissues, but not adult tissues, suggests that unique features of TFPIα, such as K3, the basic C-terminal region and/or its association with a GPI-anchored binding protein, perform specific functions in the regulation of intravascular TF/FVIIa and/or FXa activity during vasculogenesis/angiogenesis that are not performed by TFPIβ or TFPIγ.

Conclusion

The past twenty-two years has seen the isolation and basic characterization of TFPI, including identification of multiple isoforms and differences in isoform expression between species. Many unanswered questions of TFPI biology still remain. For instance, are there any in vivo functional differences between the different TFPI isoforms? Does TFPI have a role in physiological processes other than coagulation? What are the functions of the different pools of TFPI in vivo? How is production of the different isoforms regulated?

Acknowledgments

AEM is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. Funding was provided by NHLBI (R01HL068835 to AEM and K01HL096419 to SAM) and Novo Nordisk. The study sponsors had no involvement in study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- TF

Tissue factor

- TFPI

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- K1

first Kunitz domain

- K2

second Kunitz domain

- K3

third Kunitz domain

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

AEM-research grant from Novo Nordisk

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Carson SD. Plasma high density lipoproteins inhibit the activation of coagulation factor X by factor VIIa and tissue factor. FEBS Lett. 1981;132:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders NL, Bajaj SP, Zivelin A, Rapaport SI. Inhibition of tissue factor/factor VIIa activity in plasma requires factor X and an additional plasma component. Blood. 1985;66:204–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broze GJ, Jr, Miletich JP. Isolation of the tissue factor inhibitor produced by HepG2 hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1886–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:1087–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelmann B. Initiation of coagulation by tissue factor carriers in blood. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2006;36:188–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drake TA, Ruf W, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Functional tissue factor is entirely cell surface expressed on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human blood monocytes and a constitutively tissue factor-producing neoplastic cell line. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:389–395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giesen PL, Rauch U, Bohrmann B, Kling D, Roque M, Fallon JT, Badimon JJ, Himber J, Riederer MA, Nemerson Y. Blood-borne tissue factor: another view of thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2311–2315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nossel HL, Yudelman I, Canfield RE, Butler VP, Jr, Spanondis K, Wilner GD, Qureshi GD. Measurement of fibrinopeptide A in human blood. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:43–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI107749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer KA, Kass BL, ten CH, Bednarek MA, Hawiger JJ, Rosenberg RD. Detection of factor X activation in humans. Blood. 1989;74:2007–2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girard TJ, Eddy R, Wesselschmidt RL, MacPhail LA, Likert KM, Byers MG, Shows TB, Broze GJ., Jr Structure of the human lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor gene. Intro/exon gene organization and localization of the gene to chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5036–5041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wun TC, Kretzmer KK, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Cloning and characterization of a cDNA coding for the lipoprotein- associated coagulation inhibitor shows that it consists of three tandem Kunitz-type inhibitory domains. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6001–6004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girard TJ, Warren LA, Novotny WF, Likert KM, Brown SG, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Functional significance of the Kunitz-type inhibitory domains of lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor. Nature. 1989;338:518–520. doi: 10.1038/338518a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang ZF, Broze G., Jr Consequences of tissue factor pathway inhibitor gene-disruption in mice. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen B, Holscher T, Sato Y, Pawlinski R, Mackman N. A balance between tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor is required for embryonic development and hemostasis in adult mice. Blood. 2005;105:2777–2782. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westrick RJ, Bodary PF, Xu Z, Shen YC, Broze GJ, Eitzman DT. Deficiency of tissue factor pathway inhibitor promotes atherosclerosis and thrombosis in mice. Circulation. 2001;103:3044–3046. doi: 10.1161/hc2501.092492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eitzman DT, Westrick RJ, Bi X, Manning SL, Wilkinson JE, Broze GJ, Ginsburg D. Lethal perinatal thrombosis in mice resulting from the interaction of tissue factor pathway inhibitor deficiency and factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2002;105:2139–2142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017361.39256.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maroney SA, Cooley BC, Sood R, Weiler H, Mast AE. Combined tissue factor pathway inhibitor and thrombomodulin deficiency produces an augmented hypercoagulable state with tissue-specific fibrin deposition. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:111–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novotny WF, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Purification and characterization of the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor from human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18832–18837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mast AE, Acharya N, Malecha MJ, Hall CL, Dietzen DJ. Characterization of the association of tissue factor pathway inhibitor with human placenta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:2099–2104. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000042456.84190.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broze GJ, Jr, Lange GW, Duffin KL, MacPhail L. Heterogeneity of plasma tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994;5:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindahl AK, Jacobsen PB, Sandset PM, Abildgaard U. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor with high anticoagulant activity is increased in post-heparin plasma and in plasma from cancer patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1991;2:713–721. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ott I, Andrassy M, Zieglgansberger D, Geith S, Schomig A, Neumann FJ. Regulation of monocyte procoagulant activity in acute myocardial infarction: role of tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor-1. Blood. 2001;97:3721–3726. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawley J, Lupu F, Westmuckett AD, Severs NJ, Kakkar VV, Lupu C. Expression, localization, and activity of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in normal and atherosclerotic human vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1362–1373. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caplice NM, Mueske CS, Kleppe LS, Peterson TE, Broze GJ, Jr, Simari RD. Expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in vascular smooth muscle cells and its regulation by growth factors. Circ Res. 1998;83:1264–1270. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.12.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pendurthi UR, Rao LV, Williams JT, Idell S. Regulation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor expression in smooth muscle cells. Blood. 1999;94:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novotny WF, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Platelets secrete a coagulation inhibitor functionally and antigenically similar to the lipoprotein associated coagulation inhibitor. Blood. 1988;72:2020–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maroney SA, Haberichter SL, Friese P, Collins ML, Ferrel JP, Dale GL, Mast AE. Active tissue factor pathway inhibitor is expressed on the surface of coated platelets. Blood. 2007;109:1931–1937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maroney SA, Ferrel JP, Pan S, White TA, Simari RD, McVey JH, Mast AE. Temporal expression of alternatively spliced forms of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1106–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandset PM, Abildgaard U, Larsen ML. Heparin induces release of extrinsic coagulation pathway inhibitor (EPI) Thromb Res. 1988;50:803–813. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novotny WF, Palmier M, Wun TC, Broze GJ, Jr, Miletich JP. Purification and properties of heparin-releasable lipoprotein- associated coagulation inhibitor. Blood. 1991;78:394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sevinsky JR, Rao LV, Ruf W. Ligand-induced protease receptor translocation into caveolae: a mechanism for regulating cell surface proteolysis of the tissue factor- dependent coagulation pathway. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:293–304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Piro O, Lu L, Broze GJ., Jr Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchorage of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Circulation. 2003;108:623–627. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078642.45127.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang JY, Monroe DM, Oliver JA, Roberts HR. TFPIbeta, a second product from the mouse tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) gene. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lockett JM, Mast AE. Contribution of regions distal to glycine-160 to the anticoagulant activity of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4989–4997. doi: 10.1021/bi016058n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wesselschmidt R, Likert K, Girard T, Wun TC, Broze GJ., Jr Tissue factor pathway inhibitor: the carboxy-terminus is required for optimal inhibition of factor Xa. Blood. 1992;79:2004–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HH, Vicente CP, He L, Tollefsen DM, Wun TC. Fusion proteins comprising annexin V and Kunitz protease inhibitors are highly potent thrombogenic site-directed anticoagulants. Blood. 2005:2004–2011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maroney SA, Ferrel JP, Collins ML, Mast AE. TFPIgamma is an active alternatively spliced form of TFPI present in mice but not in humans. J Thromb Haemost. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maroney SA, Cunningham AC, Ferrel J, Hu R, Haberichter S, Mansbach CM, Brodsky RA, Dietzen DJ, Mast AE. A GPI-anchored co-receptor for tissue factor pathway inhibitor controls its intracellular trafficking and cell surface expression. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1114–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piro O, Broze GJ. Comparison of cell-surface TFPIalpha and beta. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2677–2683. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]