Abstract

Background

The smallpox vaccine has more serious side effects associated with it than other live attenuated vaccines in use today. While studies have examined serum cytokines in primary vaccinees at 1 and 3-5 weeks after vaccination with the smallpox vaccine, serial measurements have not been performed nor have studies been performed in revaccinees.

Methods

We analyzed cytokine responses every other day for two weeks after vaccination in both primary vaccinees and revaccinees.

Results

Primary vaccinees had maximal levels of G-CSF on days 6-7 after vaccination, peak levels of TNF-α, sTNFR1, IFN-γ, IP-10, IL-6, and TIMP-1 on days 8 to 9 after vaccination, peak levels of sTNFR-2 and MIG on days 10 to 11 after vaccination, and peak levels of GM-CSF at days 12-13 after vaccination. Primary vaccinees were significantly more likely to have higher peak levels of IFN-γ, IP-10, and MIG after vaccination than revaccinees. Primary vaccinees were significantly more likely to have fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and headache compared with revaccinees and a longer duration of these symptoms as well as missed hours from work than revaccinees.

Conclusions

The increased symptoms observed in primary vaccinees compared with revaccinees paralleled the increases in serum cytokines in these individuals.

Keywords: vaccinia virus, smallpox vaccine, cyokines, tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma

Primary vaccination with the smallpox vaccine usually results in a papular lesion with surrounding erythema about 3 to 5 days later at the site of inoculation, followed 2 to 3 days later by a vesicle and then a pustule [1]. The pustule is surrounded by erythema and induration, reaches its maximum size between 8 to 12 days, and a scab begins to form which separates at 14 to 21 days. In adult primary vaccinees, a low grade fever was present in about 9% of persons between days 7 to 9 after vaccination with the Dryvax smallpox vaccine, and in 5% between days 10 and 12 [2]. At 7 to 9 days after vaccination, myalgias were noted in 50% of primary vaccinees, fatigue in 48%, headache in 41%, regional lymphadenopathy in 30%, chills in 18%, and nausea in 14%. About 36% of subjects were sufficiently uncomfortable after vaccination that they missed school, work, outside activities, or had difficulty sleeping. In a second study using the Aventis Pasteur smallpox vaccine in vaccinia naïve subjects, 79% of vaccinees reported fatigue, 78% myalgias, 75% headache, 62% axillary lymphadenopathy, 48% chills, 38% nausea, 25% missed activities, and 22% fever during the first 2 weeks after vaccination [3].

In contrast to primary vaccinees, persons who are revaccinated with the smallpox vaccine have a more rapid sequence of events after vaccination [1]. Erythema develops in 1 to 2 days, and the papule and pustule form more rapidly than in naïve persons. While persons with some residual cellular immunity to the vaccine may develop a vesicle that may or may not form a pustule, others with substantial prior immunity may not develop a vesicle or pustule. In one study with the Dryvax smallpox vaccine, fever was less frequent (occurring in 9%) in revaccinated adults than in primary vaccinees (occurring in 60%), but there was no significant difference in other signs and symptoms between the two groups [4]. Lymphadenopathy was present in 27% of revaccinated adults at days 6 to 8 after vaccination versus 50% of primary vaccinees at this time. The study was limited by having only 10 subjects in the primary vaccine group. Another study comparing the Dryxav smallpox vaccine in vaccinia naïve with vaccinia non-naïve adults showed that axillary adenopathy occurred in 86%, fatigue in 66%, headache in 62%, and nausea in 24% of primary vaccinees while adenopathy was present in 36%, fatigue in 38%, headache in 28%, and nausea in 8% of revaccinees [5].

Systemic side effects after smallpox vaccination have been shown to be associated with elevated serum levels of cytokines in primary smallpox vaccinees. Rock et al [6] reported increased levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α after vaccination with the Aventis Pasteur smallpox vaccine, but no differences in IL-2, IL-4, and IL-5. The authors found that persons with one or more adverse events (localized or generalized rash, lymphadenopathy, fever) after vaccination had higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-5, IL-10, and TNF-α after vaccination than at baseline. McKinney et al [7] found that serum levels of 6 cytokines (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], stem cell factor [SCF], monokine induced by IFN-γ [MIG], intercellular adhesion molecule-1 [ICAM-1], eotaxin, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 [TIMP-2]) helped to distinguish individuals with or without adverse events after vaccination. These studies compared cytokines before vaccination with a single time point at 6-9 days after vaccination in primary vaccinees. Here we compare cytokine responses in primary vaccinees with revaccinees over multiple time points shortly after vaccination and correlate them with development of symptoms after vaccination.

Methods

Research Subjects

Serial blood samples were obtained from 42 consecutive employees at the National Institutes of Health vaccinated with smallpox vaccine from March 2003 to September 2008. 27 subjects were primary vaccinees and of these, 21 received Dryvax, and 6 received ACAM2000 (a plaque purified clone of Dryvax grown in cell culture). 15 were revaccinees and all received Dryvax. Healthy employees at least 18 years old were vaccinated as a routine part of their employment either because they were laboratory workers who would be exposed to recombinant vaccinia virus, or they were health care workers who might be first responders in the event of a smallpox outbreak. The protocol was approved by the Internal Review Board of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and all patients signed a written consent. Samples were obtained before and every other day after vaccination for the first two weeks (days 2-3, 4-5, 6-7, 8-9, 10-11, 12-13, 14-15) and at 1 month after vaccination. Samples were not obtained on weekends. Serum was stored in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen until use.

Cytokine analyses

Serum cytokines were assayed in the 2 primary vaccinees and 2 revaccinees from among the first 13 subjects who had the most prominent systemic symptoms (including fever and lymphadenopathy) using the Pierce Searchlight Protein Array multiplexed sandwich-ELISA system (ThermoFischer, Rockford, IL). The following cytokines were tested for each of the 4 subjects for each time point: IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IL-16, IL-17, IL-18, IFN-α, IFN-γ, MIG, IP-10, TNF-α, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 [TNFR1], TNFR2, eotaxin, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha [MIP1α], MIP-β, MIP-3α, MIP1-3β, Rantes, Exodus, macrophage-derived chemokine [MDC], I-309, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP] 1-4, thymus and activation-regulated chemokine [TARC], melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha [GroA], nucleosome assembly protein 2 [NAP2], stromal cell-derived factor [SDF], ciliary neurotrophic factor [CNTF], epithelial-derived neutrophil activating protein 78 [ENA78], fibroblast growth factor [FGF], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], hepatocyte growth factor [HGF], lactoferrin, leukemia inhibitory factor [LIF], small inducible cytokine B11 [ITAC], L-selectin, soluble intercellular cellular adhesion molecule 1 [sICAM-1], vascular cell adhesion molecule [VCAM], lymphotactin, platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF], TIMP-1, matrix metalloproteinase [MMP]-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9. Based on the cytokines that showed the most prominent increase from baseline, the following cytokines were chosen for testing by ELISA assay in all subsequent subjects:, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, GM -CSF (Endogen-Thermo); MIG (CXCL9), sTNFR1 (TNFRSF1A), sTNFR2 (TNFRSF1B), sICAM-1 (CD54), TIMP-1, (R & D Systems); eotaxin, IP-10 (Biosource). In addition, based on the recent literature [7], G-CSF, SCF, and TIMP-2 (R &D Systems) were also tested in all subjects.

Statistical analyses

The Fischer's exact test was used to test the association between the percentage of vaccinees with symptoms in primary vaccinees versus revaccinees. This test was also used to test the association between the percentage of vaccinees with >1.5-fold cytokine increases (peak cytokine level divided by level at day 0) in primary vaccinees versus revaccinees. The duration or severity of symptoms was aggregated and the Poisson model and maximum likelihood ratio statistic were used to test the difference between primary vaccinees versus revaccinees. The Wilcoxon statistic was used to assess the differences in the peak levels of cytokines in primary vaccinees versus revaccinees.

To test for an association between cytokine levels and the presence of symptoms over time, we fit a logistic regression model for each symptom. The correlation induced by having symptom outcomes on multiple days for each subject was modeled by use of generalized estimating equations. In the logistic regression model, the response variable is the presence of symptom (1 yes and 0 no). The explanatory variables include log10 (cytokine levels+0.5), age, sex and revaccinee indicator (1 revaccinee and 0 primary vaccine). Time off from work and fever were not assessed due to the very small number of events. To address the multiple tests that were conducted, only p values less than 0.01 were deemed significant for all of the analyses performed.

Results

Primary vaccinees have a higher frequency of symptoms and prolonged duration of symptoms after vaccination than revaccinees

Healthy NIH employees between the ages of 21 to 64 received the smallpox vaccine when indicated for their employment. The mean age of the patients was 35 years old; 26 were women and 16 were men. The mean age of the 27 primary vaccinees was 27 years old (range 22-33 years) and that for the 15 revaccinees was 45 years old (range 21-64 years). 63% of primary vaccinees were female, and 60% of revaccinees were female. The mean time since the prior smallpox vaccine in revaccinees was 33 years (range 11-53 years) and the mean number of prior smallpox vaccinations in these subjects was 1.3 (range 1-3 vaccinations). Of the revaccinees, 73% had received the smallpox vaccine once before revaccination, 20% had been vaccinated twice before revaccination in this study, and 7% had been vaccinated three times before revaccination in this study.

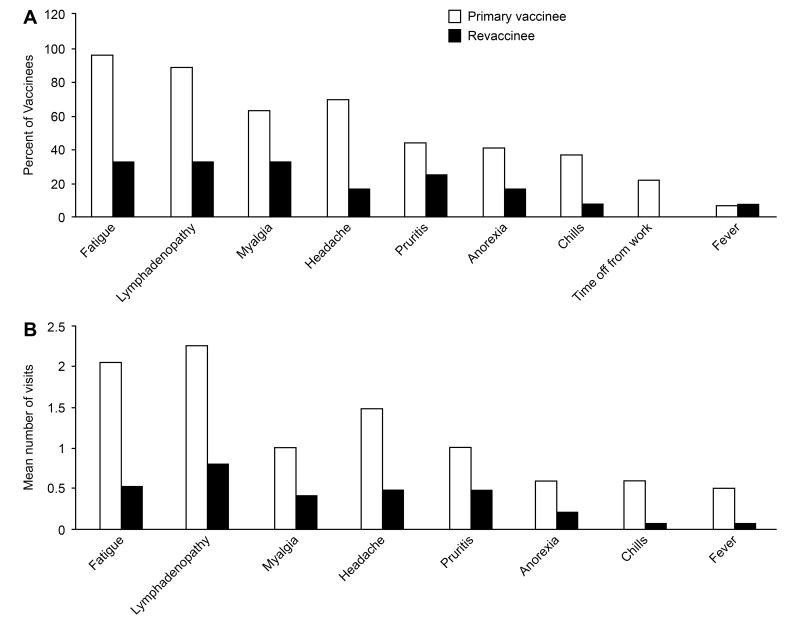

In primary vaccinees the most frequent symptoms were fatigue (96% of vaccinees), lymphadenopathy (89%), headache (70%), and myalgias (63%); other symptoms were noted in fewer than 50% of vaccinees (figure 1A). Fever (defined as a temperature ≥ 38.2°C) was noted in 7% of primary vaccinees and 22% took time off from work. Symptoms were much less common in revaccinees with fatigue in 33% of revaccinees, lymphadenopathy in 33%, and myalgias in 33%; none took time off from work.

Figure 1.

Symptoms in primary vaccinees and revaccinees receiving the smallpox vaccine. (A) Percent of vaccinees with indicated symptom and (B) Mean number of clinic visits in which symptom was reported.

Primary vaccinees were significantly more likely to have fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and headache than persons who had been revaccinated (Table 1); the differences in the frequency of other symptoms did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1. Significance of the difference in symptoms in primary vaccinees and revaccinees.

| Symptom | Frequency of symptoms in primary vs. revaccinees: P value | Duration of symptoms in primary vs. revaccinees: P value |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0.0009 | 0.0003 |

| Headache | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Myalgia | 0.163 | 0.027 |

| Pruritis | 0.31 | 0.056 |

| Loss of appetite | 0.27 | 0.054 |

| Chills | 0.12 | 0.006 |

| Fever | 1.0 | 0.01 |

| Time off from work | 0.15 | <0.0001 |

Values in bold are P<0.01.

We measured the mean duration of symptoms based on the number of clinic visits (which were every other day for the first two weeks, excluding weekends); diary card records were often incomplete and were less accurate. Primary vaccinees generally had a longer duration of symptoms than revaccinees (figure 1B). Lymphadenopathy persisted for a mean of 2.3 clinical visit days, fatigue for 2.0 visit days, headache for 1.5 visit days, and myalgias for 1 visit day. Primary vaccinees took a mean of 1.8 hours off from work after vaccination. In contrast, none of the revaccinees had symptoms that persisted for a mean of 1 or more clinic visit days, and none took time off from work after vaccination.

Primary vaccinees had a significantly longer duration of fatigue, lymphadenopathy, headache, chills, and time off from work than persons who had been revaccinated with the smallpox vaccine (Table 1).

Primary vaccinees are significantly more likely to have increased levels of sTNFR2 and G-CSF after vaccination than revaccinees

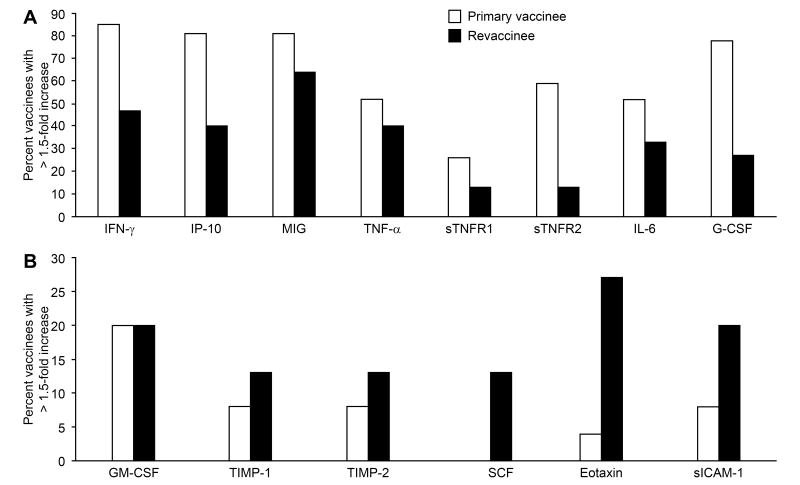

Serum cytokine levels were measured before vaccination and every other day after vaccination for two weeks. Over 50% of primary vaccinees had >1.5-fold increases in serum levels of IFN- γ, IP-10, MIG, and G-CSF, while 40 to 50% of vaccinees had >1.5-fold increases in serum levels of TNF- α, sTNFR-2, and IL-6.

Primary vaccinees were more likely to have elevations in serum cytokines than revaccinees (figure 2). Over 75% of primary vaccinees had >1.5-fold increased in levels of IFN-γ, IP-10, MIG, and G-CSF. 50%-60% had >1.5-fold increases in levels of TNF-α, sTNFR-2, and IL-6, while 20-30% had >1.5-fold increases in levels of sTNFR1 and GM-CSF. In contrast in revaccinees, the only cytokine that increased >1.5-fold in more than 50% of patients was MIG, and 40-47% of revaccines had >1.5-fold increases in IFN-γ, IP-10, and TNF-α. Increases of >1.5-fold in IL-6, G-CSF, sTNFR1, and sTNRF2 were noted in 33%, 27%, 13%, and 13% of revaccinees, respectively. The differences between primary and revaccinees for cytokine elevations of >1.5-fold were significant for sTNFR2 and G-CSF (Table 2). The level of each of these cytokines was higher in primary vaccinees than revaccinees.

Figure 2.

Percentage of vaccinees with greater than a 1.5-fold increase in cytokine levels from baseline after receiving the smallpox vaccine. Serum levels of IFN-γ, IP-10, MIG, TNF-α, sTNFR1, sTNRF2, IL-6, G-CSF (A), and levels of GM-CSF, TIMP-1, TIMP-2. SCF, eotaxin, and sICAM-1 (B) are shown.

Table 2. Significance of the difference in serum cytokines in primary and revacccinees.

| Cytokine | Cytokines increased >1.5-fold in primary vs. revaccinees: P value | Difference in peak cytokine levels in in primary vs. revaccinees: P value |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| IP-10 | 0.015 | 0.004 |

| MIG | 0.267 | 0.003 |

| TNF-α | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| sTNFR-1 | 0.451 | 0.59 |

| sTNFR-2 | 0.008 | 0.22 |

| IL-6 | 0.337 | 0.35 |

| G-CSF | 0.003 | 0.06 |

| GM-CSF | 1.0 | 0.81 |

| TIMP-1 | 0.608 | 0.07 |

| TIMP-2 | 0.608 | 0.02 |

| SCF | 0.608 | 0.61 |

| Eotaxin | 0.047 | 0.08 |

| sICAM-1 | 0.330 | 0.29 |

Values in bold are P<0.01.

GM-CSF was elevated >1.5-fold in 20% of primary vaccinees and 20% of revaccinees. TIMP-1, TIMP-2, SCF, eotaxin, and sICAM-1 were elevated >1.5-fold in less than 10% of primary vaccinees, and surprisingly were elevated >1.5-fold in a higher percentage (13% to 27%) of revaccinees.

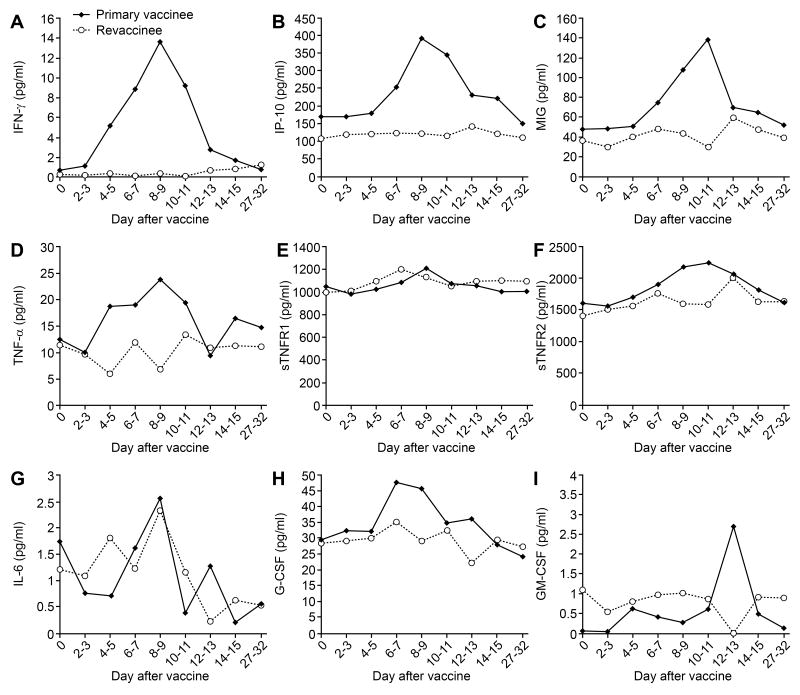

Levels of TNF-α, sTNFR-1, IFN- γ, IP10, and IL-6 peak at days 8 to 9 after vaccination, levels of sTNFR-2 and MIG peak at days 10-11, and levels of G-CSF peak at days 6-7 in primary vaccines

We measured serum level of cytokines every other day for two weeks after vaccination (figure 3). In primary vaccinees the cytokine levels typically began to rise 4-5 days after vaccination and reached peak levels at 8-11 days. In primary vaccinees the levels of G-CSF peaked at 6-7 days after vaccination, TNF-α, sTNFR1, IFN-γ, IP-10, IL-6, and TIMP-1 (data not shown) peaked at 8-9 days after vaccination. Levels of sTNFR2 and MIG peaked at 10-11 days after vaccination, while levels of GM-CSF peaked at day 12-13 after vaccination. Little change was noted in the levels of TIMP-2, SCF, eotaxin, and sICAM-1 in primary vaccinees (data not shown). In contrast to primary vaccines, the level of cytokines in revaccinees generally showed little or no change, with the possible exception of IL-6 which fluctuated widely for the first 9 days (figure 3). The difference in the peak levels of cytokines between primary and secondary vaccinees was significant for IFN-γ, IP-10, and MIG (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Serum cytokine levels over time in primary vaccinees and revaccinees receiving the smallpox vaccine. Serum levels of IFN-γ (A), IP-10 (B), MIG (C), TNF-α (D), sTNFR1 (E), sTNRF2 (F), IL-6 (G), G-CSF (H), GM-CSF (I) are shown.

Increases in levels of several serum cytokines correlate with symptoms over time

We tested for an association between the level of serum cytokines and the percentage of vaccinees with symptoms for all of the subjects, regardless of whether they were primary vaccinees or revaccines. Levels of several cytokines showed a significant (p<0.01) correlation with certain symptoms over time (Table 3). For the four serum cytokines that showed a significant correlation with two or more symptoms, the levels of cytokines over time correlated with the percentage of vaccinees with symptoms (figure 4).

Table 3. Significant (p<0.01) correlations for symptoms and the level of serum cytokines for all vaccinees over time.

| Symptom | Cytokine |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | IFN-γ (p=0.0016), IL-6 (p=0.0001), IP10 (p=0.0007), |

| MIG (p<0.0001), G-CSF (p=0.006) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | IFN-γ (p<0.0001), IP10 (p=0.009), |

| Myalgia | IFN-γ (p=0.008), MIG (p=0.0004), G-CSF (p=0.0017) |

| Pruritis | sICAM-1 (p=0.004) |

| Chills | G-CSF (p=0.0009), GM-CSF (p<0.0001) |

Figure 4.

Serum cytokines levels and symptoms over time for all vaccinees receiving the smallpox vaccine. Percent of patients with given symptoms (A) and serum levels of IFN-γ (B), IP-10 (C), MIG (D), and G-CSF (D) on different days are shown.

Discussion

We have found that serum levels of several cytokines, particularly involving the TNF-α and IFN-γ signaling pathways are increased after primary vaccination with the smallpox vaccine, and a higher frequency of primary vaccinees have elevated serum cytokines than repeat vaccineees. The elevation of serum cytokines paralleled the increase in symptoms after vaccination in primary vaccinees compared to revaccinees.

Primary vaccinees tended to be younger (mean age 27) compared to revaccinees (mean age 45), and it was possible that the more robust cytokine response to vaccination in the primary vaccinees was a result of their younger age. However, comparison of the three revaccinees whose ages were in the range of those of the primary vaccinees indicated that their cytokine responses were no more robust after vaccination than the other revaccinees (data not shown).

Previous studies have reported an increase in systemic side effects in persons with elevated levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-5, and IL-10 [6]. A follow-up study found that serum levels of G-CSF, SCF, MIG, ICAM-1, eotaxin, and TIMP-2 separated individuals with side effects from those without side effects after smallpox vaccination [7]. We found that primary vaccinees were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of sTNFR2 and G-CSF than revaccinees. Therefore sTNFR2 and G-CSF seem to correlate with the likelihood of having more symptoms after vaccination in these studies.

We found that serum levels of IFN-γ, MIG, and IP10 were increased after vaccination with the smallpox vaccine. IFN-γ regulates activity of macrophages, monocytes, and NK cells, induces MHC class II expression, and increases TH1 cell maturation. IFN-γ induces expression of IP-10 and MIG which recruit NK and T cells to sites of inflammation. The importance of IFN-γ, MIG, and IP10 in controlling poxvirus infections has been shown in several studies. Mice deficient for IFN-γ are more susceptible to certain poxviruses [8] and IFN-γ receptor knock-out mice have more severe infection with vaccinia virus than wild-type mice [9]. Intranasal administration of IFN-γ improves survival of mice inoculated with vaccinia virus [10]. Recombinant vaccinia virus encoding IFN-γ is less virulent in mice [11]. Vaccinia virus expressing MIG or Crg-2 (the murine homolog of IP-10) is attenuated in mice and anti-IFN-γ antibody increases the titer of the recombinant vaccinia viruses, but not wild-type virus [12].

The importance of IFN-γ for vaccinia virus infection is demonstrated by the observation that the virus has developed several mechanisms to block the effect of the cytokine. Vaccinia virus encodes the B8R protein that has sequence homology to the extracellular domain of IFN-γ receptors, binds to IFN-γ, and inhibits the antiviral activity IFN-γ [13]. The vaccinia virus IFN- γ receptor B8R protein has a low affinity for binding mouse IFN-γ and therefore it was not unexpected that deletion of the B8R gene from the virus did not affect virulence in mice [14]. However, another study using a different strain of mice and different B8R mutant found that vaccinia virus deleted for B8R was reduced for virulence in mice, suggesting that B8R might interact with other immunomodulatory proteins [15]. Deletion of the B8R homolog in ectromelia virus, a mouse poxvirus, reduced the virulence of the virus and was associated with higher levels of IFN-γ and enhanced cell-mediated immunity to the virus [16]. The vaccinia virus double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding protein, E3, inhibits the activity of several interferons, including IFN-γ [17]. The vaccinia virus IL-18 binding protein (c12L) inhibits IFN-γ production, inhibits NK cell and vaccinia virus-specific T cell cytotoxicity, and enhances virulence of vaccinia virus [18]. Vaccinia virus contains a phosphatase (VH1) that dephosphorylates Stat1 and blocks IFN-γ signaling [19].

We found that serum levels of TNF-α, sTNFR-1, and sTNRF-2 were increased after vaccination with vaccinia virus. TNF-α increases the cytotoxicity of leukocytes and enhances NK cell activity. sTNFR1 regulates TNF-α and in some studies gives a better indication of TNF-α biologic activity than TNF-α which has a very short half life in the circulation [20]. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of TNF-α in controlling infection with vaccinia virus. Treatment of mice with TNF-α results in reduced replication of virus in the ovaries [21]. Recombinant vaccinia virus encoding TNF-α is less virulent than parental virus in mice [22]. Mice deficient for TNF receptors are more susceptible to certain poxviruses [23]. The vaccinia virus E3L protein inhibits expression of TNF-α [24]. Some strains of vaccinia virus contain crmE which encodes both cell surface and soluble TNF receptors that inhibit the activity of TNF; virus lacking the TNF receptor is attenuated [25]. Certain stains of vaccinia virus encode crm C which encodes a soluble TNF receptor that binds to TNF receptor and blocks binding of TNF to host cells [26]. Vaccinia virus encodes a serpin that inhibits the IL-1β enzyme and protect cells from TNF-induced apoptosis [27].

Serum levels of G-CSF and IL-6 were also increased after vaccination with vaccinia virus. G-CSF enhances granulocyte production and function. IL-6 induces B cell and T cell differentiation and growth. Mice deficient in IL-6-have impaired cytotoxic T-cell activity against vaccinia virus [28] and impaired IgA responses to the virus [29]. The vaccinia virus E3L protein inhibits expression of IL-6 [24].

While serum levels of eotaxin were increased after vaccination with the smallpox vaccine, primary vaccinees were less likely to have increased levels of eotaxin than revaccinees. Eotaxin recruits eosinophils and basophils to sites of inflammation. Vaccinia virus CC chemokine binding protein reduces eosinophil infiltration in the skin of guinea pigs induced by eotaxin [30]. Eosinophils were the prominent inflammatory cells in the heart of two patients with vaccinia-associated myocarditis [31]. The reason why a higher proportion of revaccinees had elevated levels of eotaxin compared to primary vaccinees is unknown, although it is interesting to note that cardiac adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination were reported more often in revaccinees primary vaccinees [32].

Our finding that primary vaccinees are significantly more likely to have symptoms as well as increased levels of cytokines after vaccination than revaccinees parallels other observations that severe adverse events (including postvaccinia encephalitis, eczema vaccinatum, and generalized vaccinia) occurred 10 times more often in primary vaccinees than revaccinees [33]. These results, and the observation that elevated serum cytokines are correlated with more serious adverse events after vaccination [6,7] suggest that cytokines may have a role in development of serious adverse events after vaccination, and that persons with marked cytokine responses to antigenic stimulation might be more susceptible to such events.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. We thank Patricia Aldridge for assistance with patient care, Dean Follmann for statistical insights, and the many NIH employees who participated in the study.

The work has not been presented at a meeting.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00325975.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jerek Z, Ladnyi ID. Smallpox and its eradication. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frey S, Couch RB, Tacket CO, et al. Clinical responses to undiluted and diluted smallpox vaccine. N Eng J Med. 2002;346:1265–1274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot TR, Stapleton JT, Brady RC, et al. Vaccination success rate and reaction profile with diluted and undiluted smallpox vaccine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1205–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.10.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frey SE, Newman FK, Yan L, Lottenbach KR, Belshe RB. Response to smallpox vaccine in persons immunized in the distant past. JAMA. 2003;289:3295–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg RN, Kennedy JS, Clanton DJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of new cell-cultured smallpox vaccine compared with calf-lymph derived vaccine: a blind, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:398–409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rock MT, Yoder SM, Talbot TR, Edwards KM, Crowe JE., Jr Adverse events after smallpox immunizations are associated with alterations in systemic cytokine levels. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1401–10. doi: 10.1086/382510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinney BA, Reif DM, Rock MT, Edwards KM, Kingsmore SF, Moore JH, et al. Cytokine expression patterns associated with systemic adverse events following smallpox immunization. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:444–53. doi: 10.1086/505503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ, Karupiah G, Rolph MS, Mahalingam S, Ruby JC. Cytokines and immunity to viral infections. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:119–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantin E, Tanamachi B, Openshaw H, Mann J, Clarke K. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) receptor null-mutant mice are more susceptible to herpes simplex virus type 1 infection than IFN-γ ligand null-mutant mice. J Virol. 1999;73:5196–200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5196-5200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G, Zhai Q, Schaffner DJ, Wu A, Yohannes A, Robinson TM, et al. Prevention of lethal respiratory vaccinia infections in mice with interferon-alpha.and interferon-gamma. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:201–6. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohonen-Corish MR, King NJ, Woodhams CE, Ramshaw IA. Immunodeficient mice recover from infection with vaccinia virus expressing interferon-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:157–61. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahalingam S, Farber JM, Karupiah G. The interferon-inducible chemokines MuMig and Crg-2 exhibit antiviral activity In vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:1479–91. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1479-1491.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcamí A, Smith GL. Vaccinia, cowpox, and camelpox viruses encode soluble gamma interferon receptors with novel broad species specificity. J Virol. 1995;69:4633–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4633-4639.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symons JA, Tscharke DC, Price N, Smith GL. A study of the vaccinia virus interferon-gamma receptor and its contribution to virus virulence. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1953–64. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verardi PH, Jones LA, Aziz FH, Ahmad S, Yilma TD. Vaccinia virus vectors with an inactivated gamma interferon receptor homolog gene (B8R) are attenuated In vivo without a concomitant reduction in immunogenicity. J Virol. 2001;75:11–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.11-18.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakala IG, Chaudhri G, Buller RM, Nuara AA, Bai H, Chen N, et al. Poxvirus-encoded gamma interferon binding protein dampens the host immune response to infection. J Virol. 2007;81:3346–53. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01927-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arsenio J, Deschambault Y, Cao J. Antagonizing activity of vaccinia virus E3L against human interferons in Huh7 cells. Virology. 2008;377:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reading PC, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus interleukin-18-binding protein promotes virulence by reducing gamma interferon production and natural killer and T-cell activity. J Virol. 2003;77:9960–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9960-9968.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najarro P, Traktman P, Lewis JA. Vaccinia virus blocks gamma interferon signal transduction: viral VH1 phosphatase reverses Stat1 activation. J Virol. 2001;75:3185–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3185-3196.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thijs LG, Hack CE. Time course of cytokine levels in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21 2:S258–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01740764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lidbury BA, Aston R, Ramshaw IA, Cowden WB, Rathjen DA. The enhancement of human tumor necrosis factor-alpha antiviral activity in vivo by monoclonal and specific polyclonal antibodies. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1993;12:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambhi SK, Kohonen-Corish MR, Ramshaw IA. Local production of tumor necrosis factor encoded by recombinant vaccinia virus is effective in controlling viral replication in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4025–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruby J, Bluethmann H, Peschon JJ. Antiviral activity of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is mediated via p55 and p75 TNF receptors. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1591–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myskiw C, Arsenio J, van Bruggen R, Deschambault Y, Cao J. Vaccinia virus E3 suppresses expression of diverse cytokines through inhibition of the PKR, NF-kappaB, and IRF3 pathways. J Virol. 2009;83:6757–68. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02570-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reading PC, Khanna A, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus CrmE encodes a soluble and cell surface tumor necrosis factor receptor that contributes to virus virulence. Virology. 2002;292:285–98. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alcamí A, Khanna A, Paul NL, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus strains Lister, USSR and Evans express soluble and cell-surface tumour necrosis factor receptors. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:949–59. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kettle S, Alcamí A, Khanna A, Ehret R, Jassoy C, Smith GL. Vaccinia virus serpin B13R (SPI-2) inhibits interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme and protects virus-infected cells from TNF- and Fas-mediated apoptosis, but does not prevent IL-1beta-induced fever. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:677–85. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-3-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, et al. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsay AJ, Husband AJ, Ramshaw IA, Bao S, Matthaei KI, Koehler G, et al. The role of interleukin-6 in mucosal IgA antibody responses in vivo. Science. 1994;264:561–3. doi: 10.1126/science.8160012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alcamí A, Symons JA, Collins PD, Williams TJ, Smith GL. Blockade of chemokine activity by a soluble chemokine binding protein from vaccinia virus. J Immunol. 1998;160:624–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy J, Wright R, Bruce GK, et al. Eosinophilic lymphocytic myocarditis after smallpox vaccination. Lancet. 2003;362:1378–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casey CG, Iskander JK, Roper MH, et al. Adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination in the United States, January-October 2003. JAMA. 2005;294:2734–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.21.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane JM, Ruben FL, Neff JM, Millar JD. Complications of smallpox vaccination, 1968. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:1201–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196911272812201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]