Abstract

Salmonellosis is an important zoonotic disease that affects both people and animals. The incidence of reptile-associated salmonellosis has increased in Western countries due to the increasing popularity of reptiles as pets. In Korea, where reptiles are not popular as pets, many zoos offer programs in which people have contact with animals, including reptiles. So, we determined the rate of Salmonella spp. infection in animals by taking anal swabs from 294 animals at Seoul Grand Park. Salmonella spp. were isolated from 14 of 46 reptiles (30.4%), 1 of 15 birds (6.7%) and 2 of 233 mammals (0.9%). These findings indicate that vigilance is required for determining the presence of zoonotic pathogen infections in zoo animals and contamination of animal facilities to prevent human infection with zoonotic diseases from zoo facilities and animal exhibitions. In addition, prevention of human infection requires proper education about personal hygiene.

Keywords: reptile-associated salmonellosis, salmonella, zoo animal, zoonotic disease

Introduction

Salmonellosis is one of the most important zoonotic diseases that affect both people and animals [6]. For example, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States has estimated that Salmonella caused 1.4 million episodes of infection between 1999 and 2003, with over 7% of these infections caused by reptile-associated salmonellosis. Reptiles have become increasingly common as domestic pets, and there has been an associated increased incidence of reptile-associated Salmonella infection in humans [5,14,17]. Reptiles are asymptomatic carriers of Salmonella infection, and they intermittently excret these organisms in their feces [1].

Salmonella infections can be fatal in humans, and especially for those who are immature or immunocompromised, including babies, children younger than 5 years of age, pregnant women, elderly people and people with AIDS. The US CDC has recommended that these individuals should avoid contact with reptiles and that they should not keep pet reptiles in their homes [8,17].

Since reptiles are not popular pets in Korea, people most frequently come into contact with reptiles in zoos. In modern zoos, animals are kept in more natural environmental surroundings, with harmless animals, including nonpoisonous reptiles and docile mammals, often allowed to roam freely in natural looking exhibits. In particular, there are no fences, so visitors can touch these animals and make contact with the animals' feces and their living environment. Furthermore, many events at zoos allow visitors to become more familiar with the animals. In addition to direct transmission via animals to humans, Salmonella, which is relatively resistant to the environment, can be indirectly transmitted to humans through contact with the infected exhibit furnishings. For example, 39 children who attended a Komodo dragon exhibit at the Denver Zoo in Colorado in 1996 became infected with Salmonella, although none touched the animals [1,4]. In the Denver Zoo case, only a fence separated the visitors from the Komodo dragons and the dragons were allowed to wander freely behind the fence, suggesting that the 39 children became infected by contact with the Salmonella infected wooden barrier.

In addition to reptiles, mammals in a zoo can be infected by Salmonella spp. Moreover, if one animal in an exhibit or cage is infected, then it can transmit the infection to all the other animals in the same exhibit or cage [14]. Furthermore, animals in an outdoor exhibit can be contaminated with Salmonella by contact with wild animals (e.g. birds, rats etc.) [10]. To determine the risk of Salmonella infection from human-to-animal contact in Korea, we assessed the rate of Salmonella spp. infection for the animals kept at Seoul Grand Park, Korea.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

From September to October 2006, fecal samples were obtained by anal or cloacal swabs from 294 animals (46 reptiles, 14 birds and 233 mammals) housed at Seoul Grand Park, Korea (Table 1). The swabs were placed in sterile Ames transport medium (Difco, USA) and they were stored at 4℃ for 24-48 h prior to processing.

Table 1.

Distribution of the examined samples from the animals in Seoul Grand Park

Isolation of Salmonella

The samples were selectively enriched for Salmonella by incubating the swabs in tetrathionate broth (Difco, USA) at 37℃ for 24-48 h. The selective enrichment cultures were streaked onto Salmonella Chromogenic Agar (Oxoid, UK) and this was incubated at 37℃ for 24 h [3]. Violet colored colonies suspected of being Salmonella spp. were inoculated onto API20E biochemical profiles (bioMerieux SA, France).

Antimicrobial resistance test (re-isolation after freezing)

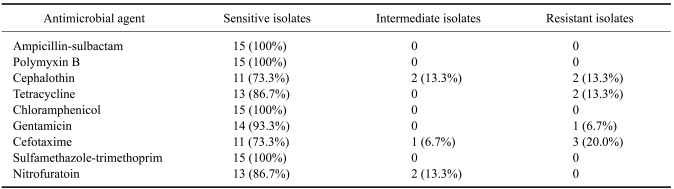

The 15 Salmonella isolates were grown from 17 stocks. The stocks were made after first isolation in this experiment and then were stored in -20℃ for a year. 5 ml aliquots of cultured buffered peptone water were inoculated onto Mueller-Hinton (Oxoid, UK) agar plates with using a sterilized swab, followed by placing antibiotic discs that contained ampicillin-sulbactam 20 µg, polymyxin B 300 µg, cephalothin 30 µg, tetracycline 30 µg, chloramphenicol 30 µg, gentamicin 10 µg, cefotaxime 30 µg, sulfamethazole-trimethoprim 25 µg or nitrofuratonin 300 µg onto the agar plates, respectively. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 35℃, and the zones of inhibition were interpreted by the guideline of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS, 1990).

Serotyping

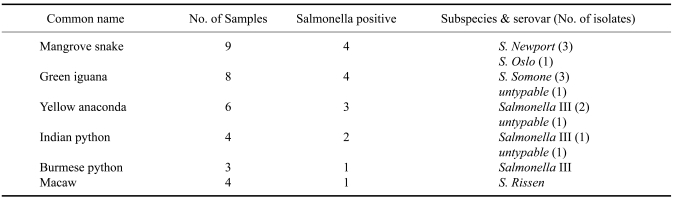

Fifteen Salmonella spp. positive samples identified with API20E were serotyped, with using the Kaufmann-White scheme, by the National Veterinary Research Quarantine Service (Table 2). The presence of Salmonella spp. subspecies III was confirmed by utilization of malonate broth (Difco, USA) and the absence of dulcitol fermentation (Biolife, Italy).

Table 2.

Number of detected Salmonella spp. and the results of serotyping

Results

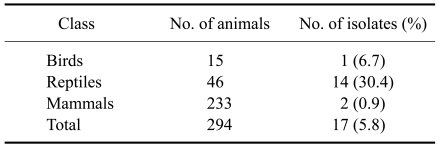

Salmonella spp. was isolated from 17 of the 294 (5.8%) anal swab samples (from 14 of 46 reptiles (30.4%), 1 of 15 birds (6.7%) and 2 of 233 mammals) (0.9%) (Table 3). Seventeen isolates were selected according to the biochemical profiles with using API20E. After about a year of storage at -20℃, these 17 Salmonella positive samples were re-inoculated. This yielded 15 positives, which were then tested for their antimicrobial susceptibility and serotype (Tables 2 and 4).

Table 3.

Distribution of the Salmonella isolates by the type of animal

Table 4.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the 15 Salmonella isolates

Discussion

Human infection by reptile-associated salmonellosis has been increasing throughout the world because more people have started keeping exotic pets, including turtles, snakes and iguanas [8,12]. In 1975, legislation in the USA banned the sale of small turtles, which led to an 18% reduction of salmonellosis in children 1-9 years old [17]. Yet zoo visitors becoming infected with Salmonella is not common, although 39 children visiting the Denver zoo in 1996 became infected [7]. Between 1966 and 2000, there have been 11 published zoonotic disease outbreaks associated with animal exhibits, as well as 16 unpublished outbreaks [2]. Therefore, although zoonotic disease outbreaks from zoos or animal exhibitions are infrequent, zoo visitors and zookeepers are at risk of infection from animal carriers. The purpose of this research was to ascertain the rate of Salmonella spp. rate in zoo animals at Seoul Grand Park, Korea. Fecal samples were collected from 294 animals (46 reptiles, 15 birds and 233 mammals), and Salmonella spp. strains were found in 14 (30.4%), 1 (6.7%) and 2 (0.9%) of these animals, respectively.

Of the 15 Salmonella isolates we examined, 8 belonged to subspecies I and 4 belonged to subspecies III, with the other 3 could not be typed. Subspecies I is responsible for more than 99% of Salmonella infections in humans [16]. Generally, Salmonella subspecies I is found in warm blooded animals, whereas subspecies II, IIIa, IIIb and IV are isolated from cold-blooded vertebrates and their environments. However, the most common subspecies isolated from reptiles was recently reported to be subspecies I [8,12].

The most frequent serovar was S. enterica Newport, a pathogen of growing importance because of its epidemic spread in dairy cattle and its increasing rate of antimicrobial resistance. Between 1987 and 1997, this serotype was the fourth most common strain seen in human salmonellosis cases in the US [13,15]. This serovar was also identified in Japan as a cause of human gastroenteritis [12]. The S. enterica Newport isolated in this study originated from mangrove snakes, suggesting that the prevalence of Salmonella spp. in reptiles may be caused by asymptomatic carriers. Reptiles could then excrete these organisms into the environment and so infect zookeepers and other humans [10]. Evaluation of the environmental spread of Salmonella strains in the reptile department of the Antwerp Zoo found contamination of the floor, window benches, cage furniture, the kitchen used for preparing animal food, water containers and fences [1], suggesting that people can be infected with Salmonella spp. by indirect transmission through contaminated environments [4,18].

We also isolated Salmonella spp. from green iguanas. Iguanas have become more popular as pets and so they play an important role in reptile-associated salmonellosis [8]. Therefore, zoos should take care prior to offering 'opportunities to touch reptiles' to their visitors.

Although most reptiles at Seoul Grand Park are kept in their own cages, the turtles and Korean terrapins are kept in a more natural environment that basically resembles a small stream. These animals can therefore roam freely around a fish tank surrounded by rocks and wooden fences, and visitors can touch these surroundings. In addition, Burmese pythons are very docile and they are frequently used in reptile contact programs. Of the 3 Burmese pythons we tested, 1 was an asymptomatic Salmonella carrier. Since many zoos have programs in which humans can feed and touch animals, this can lead to infection of children and immunocompromised individuals. Fortunately, most of the isolated Salmonella spp. in our study were susceptible to most antibiotics.

Our results emphasize the importance of surveillance of zoonotic bacterial infections in zoo animals. Our findings also highlight the requirement for better personal hygiene practices to minimizing the risk of infection for zoo visitors and the zoo personnel, as well as the need for educating zoo personal and visitors about proper hygiene practices.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Konkuk University.

References

- 1.Bauwens L, Vercammen F, Bertrand S, Collard JM, De Ceuster S. Isolation of Salmonella from environmental samples collected in the reptile department of Antwerp Zoo using different selective methods. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender JB, Shulman SA. Reports of zoonotic disease outbreaks associated with animal exhibits and availability of recommendations for preventing zoonotic disease transmission from animals to people in such settings. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:1105–1109. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassar R, Cuschieri P. Comparison of Salmonella chromogenic medium with DCLS agar for isolation of Salmonella species from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3229–3232. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3229-3232.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrente M, Madio A, Friedrich KG, Greco G, Desario C, Tagliabue S, D'Incau M, Campolo M, Buonavoglia C. Isolation of Salmonella strains from reptile faeces and comparison of different culture media. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Reptile-associated salmonellosis--selected states, 1996-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:1009–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebani VV, Cerri D, Fratini F, Meille N, Valentini P, Andreani E. Salmonella enterica isolates from faeces of domestic reptiles and a study of their antimicrobial in vitro sensitivity. Res Vet Sci. 2005;78:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman CR, Torigian C, Shillam PJ, Hoffman RE, Heltzel D, Beebe JL, Malcolm G, Dewitt WE, Hutwagner L, Griffin PM. An outbreak of salmonellosis among children attending a reptile exhibit at a zoo. J Pediatr. 1998;132:802–807. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geue L, Löschner U. Salmonella enterica in reptiles of German and Austrian origin. Vet Microbiol. 2002;84:79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong B, Andersson Y, Ekdahl K. Effect of regulation and education on reptile-associated salmonellosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:398–403. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KH, Kim KS, Tak RB. The distribution of Salmonella in mammals in Dalsung Park (Daegu) and genetic investigation of isolates. Korean J Vet Public Health. 2002;26:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SY, Lee HM, Kim S, Hong HP, Kwon HI. Phage typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of Salmonella typhimurium and S enteritidis isolated from domestic animals in Gyeongbuk province. Korean J Vet Serv. 2001;24:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakadai A, Kuroki T, Kato Y, Suzuki R, Yamai S, Yaginuma C, Shiotani R, Yamanouchi A, Hayashidani H. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in pet reptiles in Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:97–101. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen SJ, Bishop R, Brenner FW, Roels TH, Bean N, Tauxe RV, Slutsker L. The changing epidemiology of Salmonella: trends in serotypes isolated from humans in the United States, 1987-1997. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:753–761. doi: 10.1086/318832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schröter M, Roggentin P, Hofmann J, Speicher A, Laufs R, Mack D. Pet snakes as a reservoir for Salmonella enterica subsp. diarizonae (Serogroup IIIb): a prospective study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:613–615. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.613-615.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tappe D, Müller A, Langen HJ, Frosch M, Stich A. Isolation of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport from a partly ruptured splenic abscess in a traveler returning from Zanzibar. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3115–3117. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00844-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uzzau S, Brown DJ, Wallis T, Rubino S, Leori G, Bernard S, Casadesús J, Platt DJ, Olsen JE. Host adapted serotypes of Salmonella enterica. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125:229–255. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells EV, Boulton M, Hall W, Bidol SA. Reptile-associated salmonellosis in preschool-aged children in Michigan, January 2001-June 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:687–691. doi: 10.1086/423002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodward DL, Khakhria R, Johnson WM. Human salmonellosis associated with exotic pets. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2786–2790. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2786-2790.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]