Abstract

An eight-week-old female Cocker Spaniel was presented with ataxia, dysmetria and intention tremor. At 16 weeks, the clinical signs did not progress. Investigation including imaging studies of the skull and cerebrospinal fluid analysis were performed. The computed tomography revealed a cyst-like dilation at the level of the fourth ventricle associated with vermal defect in the cerebellum. After euthanasia, a cerebellar hypoplasia with vermal defect was identified on necropsy. A polymerase chain reaction amplification of cerebellar tissue revealed the absence of an in utero parvoviral infection. Therefore, the cerebellar hypoplasia in this puppy was consistent with diagnosis of primary cerebellar malformation comparable to Dandy-Walker syndrome in humans.

Keywords: cerebellar hypoplasia, dog, vermian defect

Congenital cerebellar abnormalities have been described in many species. Cerebellar hypoplasia associated with an in utero or a neonatal viral infection is most common in cats and cattle and has been reported in pigs, goats and chickens [5,11]. However, congenital cerebellar disorders such as genetic cerebellar malformations/cerebellar malformations of unknown causes and cerebellar abiotrophies also occur in sheep and several breeds of dogs [2,8,13]. Recently, in order to determine whether an infective etiology is involved in cerebellar malformations of dogs, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the DNA from several infectious agents was performed. Schatzberg et al. [10] described that the cause of the several disorders, previously considered idiopathic, was a secondary parvoviral infection in dogs using PCR. In this study, we describe cerebellar vermian hypoplasia diagnosed by computed tomography and necropsy in a Cocker Spaniel dog. PCR was used to determine whether parvoviral infection was present.

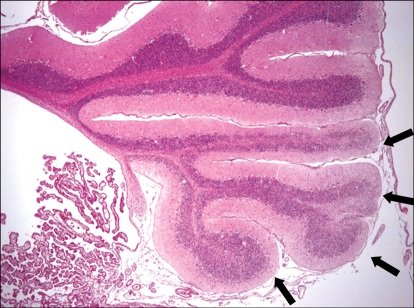

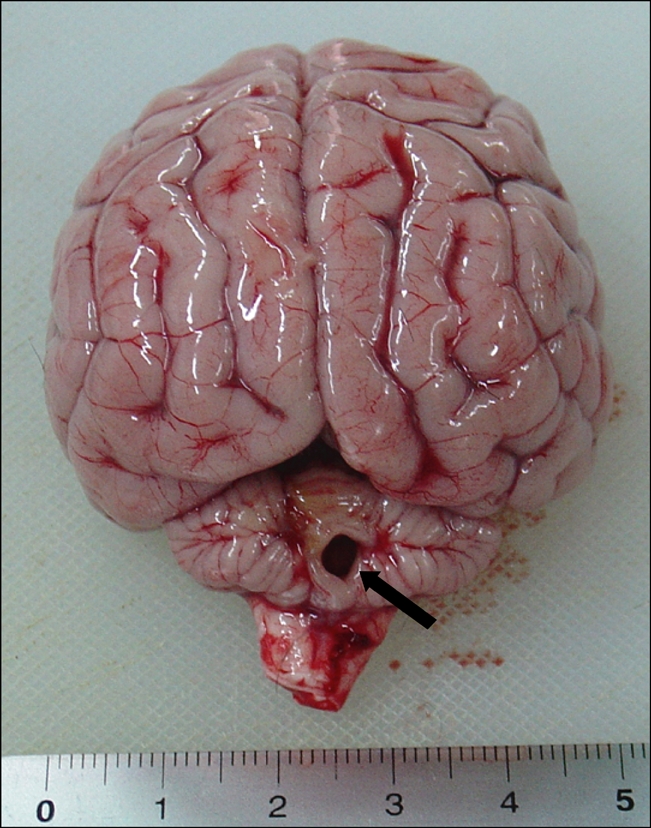

An eight-week-old female Cocker Spaniel was referred to the Seoul National University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital for evaluation of ataxia in all four limbs. The puppy was alert, responsive, and appeared in good general condition, but was unable to stand. Neurological examinations revealed ataxia, dysmetria and intention tremor in all four limbs. The puppy was re-examined at 16 weeks of age. At this time, the clinical signs had neither progressed nor improved. Survey radiography of the skull and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis were performed and normal. The canine distemper antibody titer in the CSF was also within reference range. Additional computed tomographs (CT) revealed cyst-like dilation at the level of the cerebellum (Fig. 1). The puppy was euthanized and on necropsy, the cerebral hemispheres were found to be normal in size. However, there was an obvious agenesis of the posterior cerebellar vermis (Fig. 2). The defect communicated with the fourth ventricle. The brain and cerebellum were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, cut at 3 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for light microscopic examination. Histologically, folial atrophy (Fig. 3), degeneration and loss of Purkinge cells and granular cells were found. To identify whether an in utero parvoviral infection occurred, DNA was extracted from the paraffin embedded cerebellar tissue and PCR amplification was performed using three primer pairs specific for parvovirus DNA [10]. These primer pairs are designed to amplify genes that code for structural proteins (VP1 and VP2) from both feline and canine parvovirus. In brief, the PCR of DNA from the hypoplastic cerebellum was performed for 30 cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 94℃ for 30 sec, annealing at 55℃ for 2 min and polymerization at 72℃ for 2 min and then PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.2% agarose gel. Parvoviral DNA was not amplified from the hypoplastic cerebellum in this puppy.

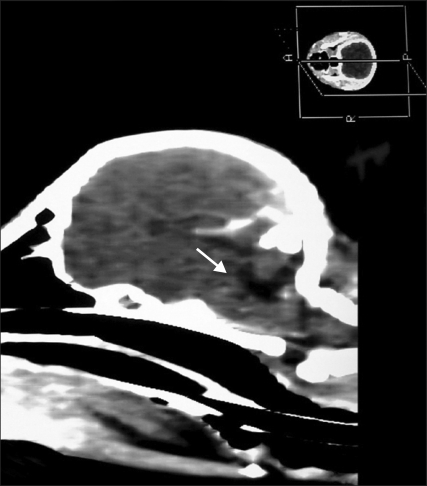

Fig. 1.

Computed tomographs revealed cyst-like dilation of the fourth ventricle and the radiolucent regions (arrow) in the cerebellar structure without herniation of cerebellum.

Fig. 2.

The cerebellum without cerebellar vermis (arrow).

Fig. 3.

Multifocal folial atrophy (arrows). H&E stain, ×12.5.

The cerebellum functions as a regulator of movements and maintenance of equilibrium. Signs of cerebellar dysfunction, therefore, usually include abnormalities of rate, range, direction and force of motor movement [9]. Structurally, the medial portion or the vermis is responsible primarily for regulating posture and muscle tone. Abnormality of this area of the cerebellum may cause ataxic gait referred to as dysmetria, which can present with hypermetria and intention tremor [1]. A primary developmental defect and a secondary malformation of the cerebellum after infection are the most common causes of congenital cerebellar malformation in animals [5,6]. Cerebellar hypoplasia and atrophy secondary to feline panleukopenia virus infection are well documented in cats [7]. In dogs, no viral etiology has been identified except the canine herpes virus, which causes extensive inflammation in multiple systems of neonatal animals. However, recently, parvoviral infection has been implicated using PCR [10,12]. Based on the study of the Schatzberg et al. [10], canine parvovirus infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis for puppies with congenital cerebellar disease. Results from studies on paraffin block specimens from dogs with cerebellar hypoplasia were negative in six dogs with vermal defect and two with abiotrophy for parvoviral DNA, and positive in two blue tick coonhound littermates with diffusely hypoplastic but no vermal defects [10]. The PCR amplification result in the present study confirmed that our dog with vermian defects had genetic etiology rather than a viral infection.

The clinical signs of the puppy in this report seemed to be due to the congenital anomalies of the cerebellum including aplasia, partial agenesis or hypoplasia. Hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis was supported by two clinical findings. First, this puppy did not show any signs of a systemic infection. Second, the clinical signs did not progress during 8 weeks of follow-up. Both clinical findings are consistent with a congenital malformation that is non-progressive and associated with normal laboratory findings [3,6]. In this study, CT scans identified the hypoattenuating regions in the cerebellum without hydrocephalus. Although magnetic resonance image (MRI) provided a more detailed information of the entire brain, the CT scan may be appropriate in diagnosing structural anomaly [13]. The cyst-like dilation of the fourth ventricle noted on the CT scan suggested a possible partial or complete defect of the cerebellar vermis. On necropsy, agenesis of the posterior cerebellar vermis consisting of the dorsal wall was also noted. However, the communication to the central canal from the fourth ventricle was normal in appearance. These features are consistent with the Dandy-Walker-like malformation described in previous reports [4,5,8]. Dandy-Walker syndrome is a condition in children with partial or complete absence of the cerebellar vermis. They also typically have cyst-like dilations of the fourth ventricle as well as hydrocephalus. However, the syndrome is associated with or without variable vermian hypoplasia and is described with or without hydrocephalus in dogs [6]. Our case had only agenesis of posterior cerebellar vermis. In human, Dandy-Walker syndrome is considered to be primary parenchymal, midline developmental defect of genetic origin [5,10]. However, the pathogenesis in dogs has not been established yet.

In the present report, a cerebellar malformation was suspected in an eight-week-old Cocker Spaniel based on clinical signs and CT scans. Necropsy confirmed cerebellar vermian hypoplasia. There was no evidence of an in utero parvoviral infection. Since the etiology of cerebellar vermian hypoplasia is unknown in dogs, it is important to evaluate littermates for a possible genetic etiology.

References

- 1.DeLahunta A. Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology. 2nd ed. Philadelpia: Saunders; 1983. pp. 260–262. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin RJ, Ramsey IK, McKerrell RE. An inherited neurological disorder of the St. Bernard dog characterised by unusual cerebellar cortical dysplasia. Vet Rec. 1997;140:656–657. doi: 10.1136/vr.140.25.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harari J, Miller D, Padgett GA, Grace J. Cerebellar agenesis in two canine littermates. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:622–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffrey M, Preece BE, Holliman A. Dandy-Walker malformation in two calves. Vet Rec. 1990;126:499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornegay JN. Cerebellar vermian hypoplasia in dogs. Vet Pathol. 1986;23:374–379. doi: 10.1177/030098588602300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noureddine C, Harder R, Olby NJ, Spaulding K, Brown T. Ultrasonographic appearance of Dandy Walker-like syndrome in a Boston Terrier. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:336–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien DP, Axlund TW. Brain disease. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 6th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelpia: Saunders; 2005. pp. 820–821. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pass DA, Howell JM, Thompson RR. Cerebellar malformation in two dogs and a sheep. Vet Pathol. 1981;18:405–407. doi: 10.1177/030098588101800315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodney S. Tremor and involuntary movements. In: Simon RP, Olby NJ, editors. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology. 3rd ed. Cheltenham: British Small Animal Veterinary Association; 2004. pp. 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schatzberg SJ, Haley NJ, Barr SC, Parrish C, Steingold S, Summers BA, deLahunta A, Kornegay JN, Sharp NJ. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of parvoviral DNA from the brains of dogs and cats with cerebellar hypoplasia. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:538–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2003.tb02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Summers BA, Cummings JF, DeLahunta A. Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Url A, Truyen U, Rebel-Bauder B, Weissenbock H, Schmidt P. Evidence of parvovirus replication in cerebral neurons of cats. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3801–3805. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3801-3805.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Merwe LL, Lane E. Diagnosis of cerebellar cortical degeneration in a Scottish terrier using magnetic resonance imaging. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:409–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2001.tb02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]