Abstract

Hybridization to RNA is important for many applications, including antisense therapeutics, RNA interference, and microarray screening. Similar thermodynamic stabilities of A-U and G-U base pairs result in difficulties in selective binding of matched and mismatched RNA duplexes. Moreover, A-U pairs are weaker than G-C pairs so that binding is sometimes weak when many A-U pairs are present. It is known, however, that replacement of uridine with 2-thiouridine significantly improves binding and selectivity. To test for additional improvement of binding and of the specificity for binding A over G, LNA-2-thiouridine was synthesized for the first time and incorporated into many LNA-2-O-methylRNA/RNA duplexes. UV melting was used to measure the thermodynamic effect of replacing 2'-O-methyluridine with 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine or LNA-2-thiouridine. The 2-thiouridine usually enhances binding and selectivity. Selectivity is optimized when a single 2-thiouridine is placed at an internal position in a duplex.

INTRODUCTION

Among the 107 naturally modified RNA nucleotides, 16 carry sulfur, including, 9 derivatives of 2-thiouridine (s2U) (1). Replacement of the pyrimidine oxygen at position 2 with sulfur changes biological and structural properties. Oxygen and sulfur have different radii (60 versus 100 pm) and electronegativity (3.5 versus 2.5 Pauling unit). Those differences influence the ability to hydrogen bond and the ribose puckering. In general, uridine and 2-thiouridine nucleosides and nucleotides adopt ca. 50–60% and 70–100% C3'-endo conformation, respectively. In consequence, 2-thiouridine derivatives influence the overall structure of helixes (2, 3).

Uridine is the least effective nucleotide to include in probes and therapeutics because it binds weakly and with low specificity to adenosine. On the basis of UV melting, CD and NMR studies, Kumar and Davis demonstrated that substitution of uridine with 2-thiouridine but not 4-thiouridine (s4U) in A-U pairs significantly enhances stabilities of RNA duplexes (3). CD and NMR experiments indicated that A-form helical structure is maintained. Imino proton NMR showed that proton exchange rates, chemical shift differences, and NH proton linewidths indicate the following stability order in A-U pairs: s2U > U > s4U. Moreover, 2-thiouridine in oligoribonucleotides enhances the specificity for binding to complementary RNA because the difference in stabilities between A-s2U and G-s2U base pairs is larger than between A-U and G-U base pairs (4). Replacing U with s2U significantly enhances thermodynamic stability of A-s2U but not G-s2U containing RNA duplexes. Parallel triplexes are also significantly stabilized by 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine (s2UM) and 2-thiothymidine, which was attributed to the effect of 2-thiocarbonyl groups on stacking (5).

The unique features of 2-thiouridine influence RNA biological function. For example, 2-thiouridine derivatives are present very often at wobble position 34 of tRNA and it is essential for ribosome binding (6, 7). The full-length, unmodified transcript of human tRNALys3UUU and unmodified tRNALys3UUU anticodon stem/loop (ASLLys3UUU) do not bind AAA- or AAG-programmed ribosomes. Single, site-specific substitution of s2U at position 34 to produce the modified ASLLys3SUU, however, restores ribosomal binding Moreover, investigations of thermodynamic stability and of structure by NMR demonstrated different dynamic conformations for the loop of modified ASLLys3SUU and unmodified ASLLys3UUU, whereas the stems were isomorphous (7–10).

Substitution by 2-thiouridine also can affect gene silencing of short interfering RNA (11). Among other modified nucleotides, introducing s2U resulted in 5–10 times more effective gene silencing of pBACE1-GFP plasmid in HeLa cells.

Locked nucleic acids (LNA) are analogues of nucleic acids where C4' and O2' are bridged with a methylene linker which fixes the ribose ring pucker to C3'-endo conformation exclusively (12, 13). Among all known modified analogues, LNA forms the most thermodynamically stable duplexes with RNA and DNA (14–18). In this paper, the chemical synthesis of LNA-2-thiouridine is described for the first time. To achieve this goal, it was necessary to change one of the protecting groups used during synthesis and to optimize the nucleoside condensation reaction to minimize S-nucleoside formation. Studies of the thermodynamic stabilities of model LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes containing either 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine or LNA-2-thiouridine demonstrated that both enhance selectivity of binding to A over G, but that LNA-2-thiouridine has a larger effect on stability. The abbreviation, LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA, means that one strand of the duplex is formed by a 2’-O-methyl-oligonucleotide with LNA nucleotide(s) (LNA-2'-OMeRNA) at selected position(s) whereas the second strand is oligoribonucleotide (RNA). The largest enhancement in selectivity occurs when s2U is at an internal position within the duplex. Similar results were observed with duplexes carrying pyrene at the 3'-side of the 2'-O-methyl-oligonucleotide strand. This latter type of duplex mimics interactions of isoenergetic microarray probes that target RNA. In those microarrays, the probes are short 2'-O-methyl-oligonucleotides and they are used to study secondary structure of target RNAs (19–24). The 2'-O-methylated oligonucleotides (2'-OMeRNA) are also useful for modulating biological functions by binding to target RNA (25–28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods

Mass spectra of nucleosides and oligonucleotides were obtained on an LC MS Hewlett Packard series 1100 MSD with API-ES detector or a MALDI TOF MS, model Autoflex (Bruker). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) purification of oligonucleotides was carried out on Merck 60 F254 TLC plates with the mixture 1-propanol/aqueous ammolonia/water = 55:35:10 (v/v/v). TLC analysis of reaction progress was performed on the same type of silica gel plates with various mixtures of dichloromethane and methanol [98:2 v/v (A), 95:5 v/v (B), 9:1 v/v (C) and 8:2 v/v (D)].

Synthesis and purification of oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems DNA/RNA synthesizer, using β-cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry (29). Commercially available A, C, G, and U phosphoramidites with 2'-O-tertbutyldimethylsilyl or 2'-O-methyl groups were used for synthesis of RNA and 2'-O-methyl RNA, respectively (Glen Research, Azco, Proligo). The 3'-O-phosphoramidites of LNA nucleotides were synthesized according to published procedures with some minor modifications (16, 17, 30, 31). The details of deprotection and purification of oligoribonucleotides were described previously (32).

UV melting

Oligonucleotides were melted in buffer containing 1 M NaCl, 20 mmol sodium cacodylate, 0.5 mmol Na2EDTA, pH 7.0. The relatively low NaCl concentration kept melting temperatures in the reasonable range even when there were multiple substitutions and also allowed comparison to previous experiments. Oligonucleotide single strand concentrations were calculated from absorbance above 80 °C (33, 34). Absorbance vs. temperature melting curves were measured at 260 nm with a heating rate of 1 °C/min from 0 to 90 °C on a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer with a thermoprogrammer. Melting curves were analyzed and thermodynamic parameters were calculated from a two-state model with the program MeltWin 3.5 (35). For most sequences, the ΔH° derived from TM−1 vs. ln (CT/4) plots is within 15% of that derived from averaging the fits to individual melting curves, as expected if the two-state model is reasonable.

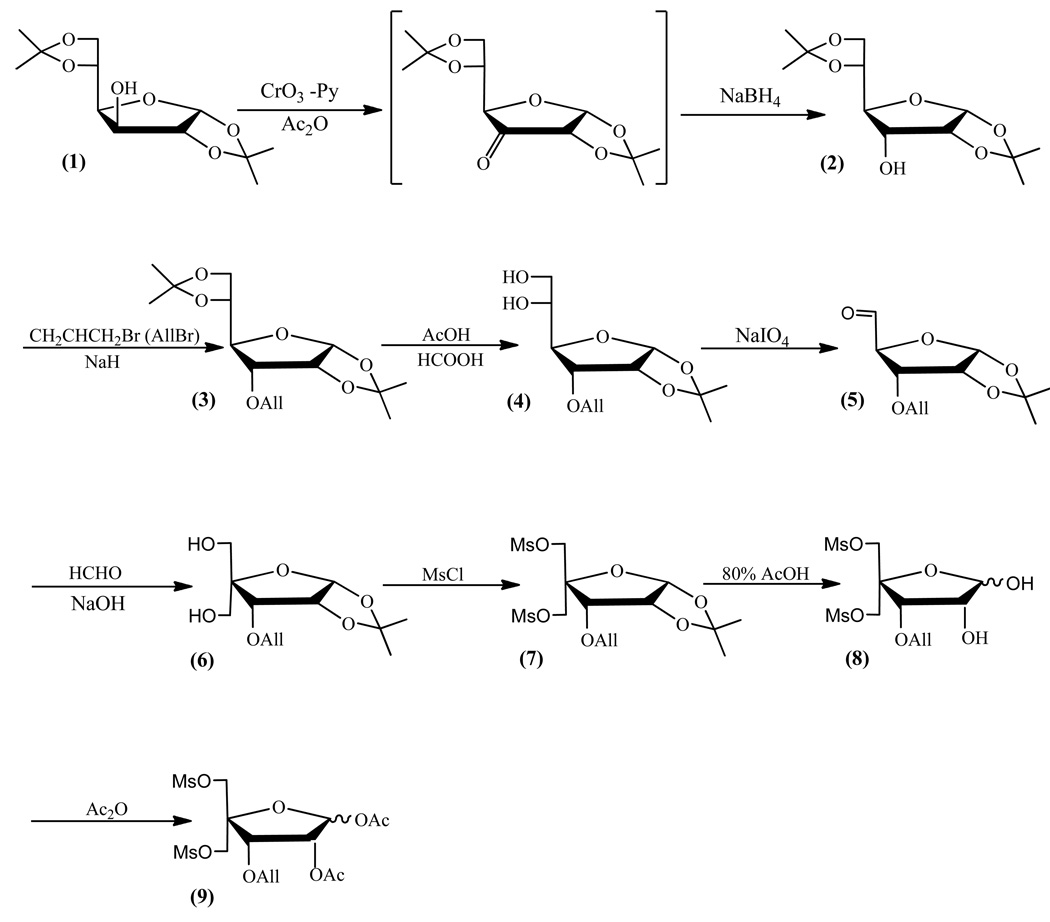

Synthesis of pentafuranose precursor (1,2-di-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose) (9)

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-1,2,5,6-di-O-isopropynylene-α-D-glucose (3)

The derivative (2) (40.7 g, 156.3 mmol) was coevaporated twice with THF and dissolved in 163 mL of anhydrous THF. Then, to a stirred solution of (2) at room temperature a 60% emulsion of sodium hydride [9.36 g (234 mmol)] in mineral oil was added and left to dissolve the sodium hydride (ca. 30 min), whereupon 21.6 mL (250 mmol) of allyl bromide was added and left stirring for 16 h. After completion, the reaction mixture volume was reduced to half, a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to heavy oil. Rf: 0.15 (A), 28 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 6.01-5.90 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.77 (1H, d, H-1), 5.38-5.24 (2H, 2x d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.65 (1H, t, H-2), 4.30-4.20 (1H, m, H-3), 4.11-4.02 (3H, m, H-5, H-1'a, H-1'b), 3.95-3.68 (3H, m, H-4, All-OCH2CHCH2), 1.60 (3H, s, CH3), 1.35 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 133.97, 118.94 (All), 113.24 (C(CH3)2), 104.17 (C-1), 77.32 (C-2), 77.00 (C-3), 76.68 (C-4), 71.31 (C-5), 70.73 (All), 64.16 (C-1'), 26.74, 26.49 (CH3).

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-1,2-O-isopropynylene-α-D-glucose (4)

To derivative (3) (47.6 g, 158.7 mmol), 127 mL of glacial acetic acid, 65 mL of formic acid and 80 mL of water were added and left stirring at room temperature for 1.5 h. After reaction completion, the reaction mixture was evaporated and coevaporated three times with toluene. Rf: 0.15 (A), 0.28 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 6.01-5.90 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.77 (1H, d, H-1), 5.38-5.24 (2H, 2x d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.65 (1H, t, H-2), 4.30-4.20 (1H, m, H-3), 4.11-4.02 (3H, m, H-5, H-1'a, H-1'b), 3.95-3.68 (3H, m, H-4, All-OCH2CHCH2), 1.60 (3H, s, CH3), 1.35 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 133.97, 118.94 (All), 113.24 (C(CH3)2), 104.17 (C-1), 77.32 (C-2), 77.00 (C-3), 76.68 (C-4), 71.31 (C-5), 70.73 (All), 64.16 (C-1'), 26.74, 26.49 (CH3).

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-5-aldehyde-1,2-O-isopropynylene-α-D-glucose (5)

To 45.5 g (175 mmol) of derivative (4) dissolved in 430 mL of ethanol, a solution of 42.2 g (192 mmol) of sodium periodite in 290 mL of water was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h at room temperature and volume reduced by half. Then, a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. Combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to heavy oil. Rf: 0.32 (A), 0.61 (B); 1H NMR, δH (CDCl3): 9.70 (1H, s, CHO); 6.02-5.84 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2); 5.80 (1H, d, H-1); 5.40-5.25 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2); 4.65 (1H, t, H-2); 4.30-4.03 (3H, m, H-3, H-4, H-5); 3.95-3.82 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2); 1.60 (3H, s, CH3); 1.30 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR, δC (CDCl3): 198.53 (CHO); 133.80, 118.89 (All); 113.94 (C(CH3)2); 104.61 (C-1); 77.32 (C-2); 77.00 (C-3); 76.68 (C-4); 71.61 (All); 26.91, 26.57 (CH3).

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-4-C-hydroxymethyl-1,2-O-isopropynylene-α-D-glucose (6)

The derivative (5) (38.3 g, 168.1 mmol) was dissolved in 170 mL of THF and 170 mL of water and cooled to 4 °C. Then, 96.3 mL (3.48 mol) of formic aldehyde and 430 mL of 1 M aqueous sodium hydroxide were added; after 10 minutes the mixture was left at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate, dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated. Rf: 0.18 (A), 0.35 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 6.01-5.88 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.77 (1H, d, H-1), 5.37-5.21 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.67 (1H, t, H-2), 4.40-3.80 (5H, m, H-3, H-5a, H-5b, H-1'a, H-1'b), 3.92-3.80 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 1.61 (3H, s, CH3), 1.35 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 133.97, 118.41 (All), 113.52 (C(CH3)2), 104.34 (C-1), 86.14 (C-4); 78.51 (C-2), 78.21 (C-3), 71.90 (C-5), 70.14 (All), 64.10 (C-1'), 26.54, 25.86 (CH3).

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-1,2-O-isopropynylene-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose (7)

Derivative (6) (44.5 g, 171.2 mmol) was dissolved in 140 mL of anhydrous pyridine and cooled to 4 °C, whereupon methanesulfonyl chloride (26.6 mL, 342 mmol) was added. After a few minutes, the reaction mixture was left at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the volume of the reaction mixture was reduced to half; a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution evaporated and coevaprated a few times with toluene. Rf: 0.56 (A), 0.85 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 5.98-5.86 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.81 (1H, d, H-1), 5.38-5.25 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.70 (1H, t, H-2), 4.40-4.05 (5H, m, H-3, H-5a, H-5b, H-1'a, H-1'b), 4.19 (2H, d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 3.12 (2H, s, CH3-Ms), 3.10 (1H, s, CH3-Ms), 3.09 (1H, s, CH3-Ms), 3.05 (1H, s, CH3-Ms), 1.68 (3H, s, CH3), 1.35 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 133.55, 118.95 (All), 114.03 (C(CH3)2), 104.46 (C-1), 83.22 (C-4), 78.39 (C-2), 77.93 (C-3), 72.14 (C-5), 69.47 (All), 68.75 (C-1'), 38.07, 37.56 (CH3-Ms), 26.19, 25.64 (CH3).

Synthesis of 3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose (8)

To derivative (7) (42.3 g, 101.6 mmol) was added 130 mL of 80% acetic acid and the mixture was refluxed for 3 h at 90 °C. After completion, the reaction mixture was evaporated and coevaporated a few times with toluene, and a few times with anhydrous pyridine. Rf: 0.05 (A), 0.21 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 5.96-5.84 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.42 (1H, s, H-1), 5.39-5.25 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.60 (1H, d, H-2), 4.43-4.05 (5H, m, H-3, H-5a, H-5b, H-1'a, H-1'b), 4.20 (2H, d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 3.08, 3.06 (6H, 2s, CH3-Ms); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 133.16, 119.30 (All), 101.45 (C-1), 82.24 (C-4), 77.31 (C-2), 76.68 (C-3), 72.70 (C-5), 69.62 (All), 68.98 (C-1'); 37.65, 37.59 (CH3-Ms).

Synthesis of 1,2-di-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose (9)

Derivative (8) (38.4 g, 102 mmol) was dissolved in 90 mL of anhydrous pyridine and 38 mL (408 mmol) of acetic anhydride was added and stirred at room temperature for 16 h. After completion, the volume of the reaction mixture was reduced to half and a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated and coevaprated a few times with toluene. The remains of mineral oil were washed out with n-hexanes. The reaction mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using dichloromethane as solvent. The overall yield for 9 steps was 37%, which corresponds on average to ca. 90% for each step. Rf: 0.66 (A), 0.78 (B); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 6.17 (1H, s, H-1), 5.87-5.77 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.38-5.30 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.28-5.22 (1H, t, H-2), 4.39 (1H, d, H-3), 4.37-4.20 (4H, m, H-5a, H-5b, H-1'a, H-1'b), 4.10-3.98 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 3.08 (3H, s, CH3-Ms), 3.07 (3H, s, CH3-Ms), 2.16 (3H, s, COCH3), 2.11 (3H, s, COCH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 169.15, 168.79 (C=O), 133.18, 118.55 (All), 97.33 (C-1), 82.73 (C-4), 78.46 (C-2), 76.99 (C-3), 73.47 (C-5), 72.96 (C-1'), 68.66 (All), 37.89, 37.71 (CH3-Ms), 21.03, 20.65 (CH3-Ac).

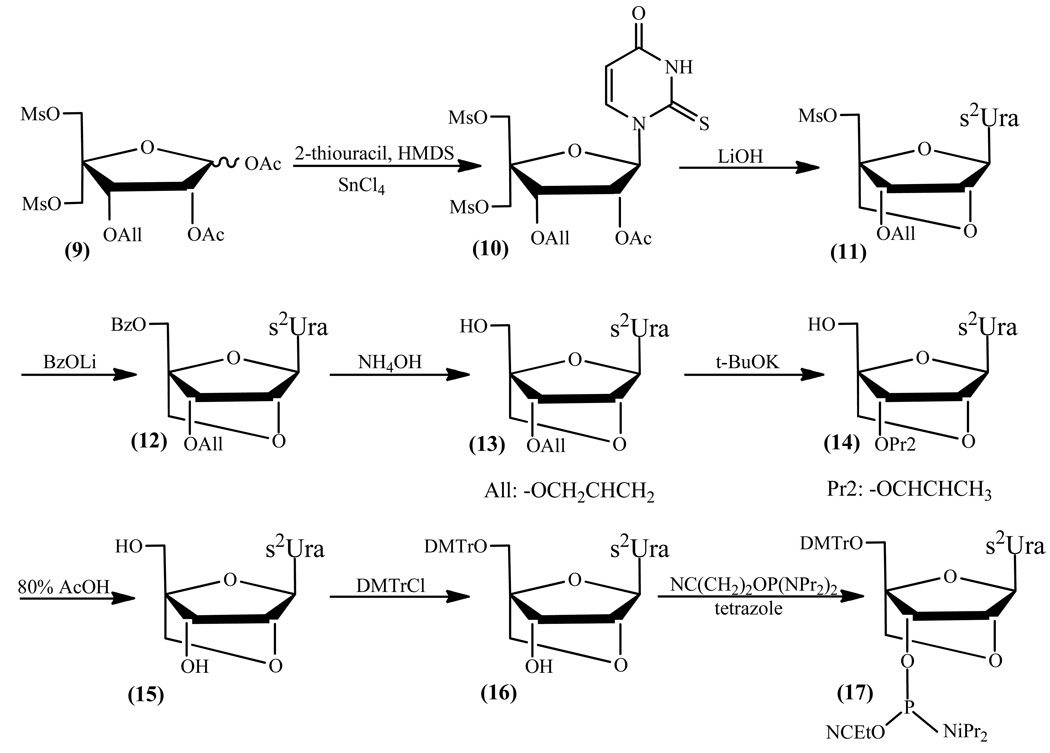

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-hydroxy-1-(4,4’-dimethoxytritylomethyl)-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (16)

Synthesis of 1-(2-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-β-D-ribofuranosyl)-2-thiouridine (10)

2-Thiouracil (12.2 g, 95 mmol) was suspended in 150 mL of hexamethyldisilazane and 50 mg of ammonium sulfate was added, and refluxed at 130 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, evaporated to dryness, and coevaporated three times with 1,2-dichloroethane. Then, 1,2-di-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose (9) (32.4 g, 70.4 mmol) that was previously coevaporated three times with 1,2-dichloroethane was added to silylated 2-thiouracil and the mixture of both substrates was coevaporated once again with 1,2-dichloroethane. The residual oil was dissolved in 340 mL of anhydrous 1,2-dichloroethane and cooled to 4 °C. Then, 16.5 mL (141 mmol) of tin chloride (IV) was added dropwise, and left at room temperature for 2 h. To the reaction mixture was added a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and sodium chloride and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated. The reaction mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using as solvent dichloromethane with gradually increasing amount of methanol (up to 2%). Yield of product (10): 27.3 g (51.6 mmol, 73.3%). Rf: 0.19 (B), 0.97 (C), 0.60 (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 7.68 (1H, d, H-6), 7.26 (1H, s, H-1'), 6.05 (1H, d, H-5), 5.91-5.78 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.30-5.20 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.67 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.53 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.25 (2H, d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.15-3.96 (4H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-5''a, H-5''b), 3.13 (3H, s, CH3-Ms), 3.10 (3H, s, CH3-Ms). 2.16 (3H, s, COCH3); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 175.72 (C-2), 169.48 (C=O), 159.85 (C-4), 139.43 (C-6), 132.94, 119.10 (All), 107.18 (C-5), 91.63 (C-1'), 84.60 (C-4'), 77.21 (C-2'), 75.60 (C-3'), 73.48 (C-5'), 67.65 (All), 53.41 (C-1''), 37.92, 37.62 (CH3-Ms), 20.75 (CH3-Ac).

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-allyloxy-1-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (11)

Derivative (10) (24.4 g, 46.2 mmol) was dissolved in 78 mL of THF and 138 mL of 1 M aqueous solution of monohydrate of lithium hydroxide was added. After 1 h stirring at room temperature, the reaction was complete and acetic acid was used to neutralize the reaction. To the reaction mixture was added a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated to dryness. Yield of the crude (11): 16.5 g (42.3 mmol, 91.5%). Rf: 0.39 (B), 0.94 (C), 0.65 (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 7.70 (1H, d, H-6), 6.12 (1H, s, H-1'), 5.97 (1H, d, H-5), 5.86-5.70 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.24-5.11 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.84 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.56 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.12-3.92 (4H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-1''a, H-1''b), 3.86 (2H, d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 3.07 (3H, s, CH3-Ms); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 174.68 (C-2), 159.75 (C-4), 139.02 (C-6), 133.08, 118.02 (All), 106.49 (C-5), 90.43 (C-1'), 86.08 (C-4'), 77.42 (C-2'), 76.99 (C-3'), 75.84 (C-5'), 68.67 (All), 64.09 (C-1''), 37.50 (CH3-Ms).

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-allyloxy-1-benzoyloxymethyl-2,5-dioksabicyclo [2.2.1]heptane (12)

The compound (11) (16.5 g, 42.3 mmol) was coevaporated three times with anhydrous DMF and residue was dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous DMF. Then, 16.3 g (127 mmol) of lithium benzoate was added and stirred for 16 h at 90 °C. After completion, a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and sodium chloride was added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated to dryness. Yield of the crude (12): 15.9 g (38.1 mmol, 90.0%). Rf: 0.66 (B), 0.97 (C), 0.51 (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 10.69 (1H, s, N-H), 8.01 (1H, d, H-6), 7.55-7.52 (5H, m, Bz), 6.14 (1H, s, H-1'), 5.90-5.79 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.76 (1H, d, H-5), 5.30-5.10 (2H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.91 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.16 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.20-3.80 (6H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-1''a, H-1''b, All-OCH2CHCH2); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 174.58 (C-2), 162.53 (Bn), 159.69 (C-4), 139.43 (C-6), 133.82, 133.28, 129.69, 128.76 (Bn), 106.14 (C-5), 92.56 (C-1'), 86.73 (C-4'), 81.42 (C-2'), 77.32 (C-3'), 75.92 (C-5'), 71.27 (All), 58.98 (C-1'').

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-allyloxy-1-hydroxymethyl-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (13)

To crude derivative (12) (15.9 g, 38.1 mmol) was added 50 mL of pyridine and 32% aqueous ammonia to beginning cloudiness of solution, and left at 55 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was evaporated and coevaporated several times with toluene. The reaction mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using as solvent dichloromethane with gradually increasing amount of methanol (up to 5%). Yield of product (13): 9.4 g (30.1 mmol, 79.1%). Rf: 0.21 (B), 0.65 (C), 0.76 (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 8.04 (1H, d, H-6), 6.12 (1H, s, H-1'), 6.04 (1H, d, H-5), 5.90-5.77 (1H, m, All-OCH2CHCH2), 5.30-5.10 (2H, 2d, All-OCH2CHCH2), 4.79 (1H, s, H-2'), 3.99 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.10-3.70 (6H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-1''a, H-1''b, All-OCH2CHCH2); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 176.00 (C-2), 161.88 (C-4), 140.27 (C-6), 133.50, 118.59 (All), 106.19 (C-5), 90.28 (C-1'), 89.07 (C-4'), 77.32 (C-2'), 76.68 (C-3'), 75.33 (C-5'), 70.01 (All), 56.65 (C-1'').

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-(prop-1-enyl)-1-hydroxymethyl-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (14)

Compound (13) (8.8 g, 28.1 mmol) was dissolved in 140 mL of anhydrous DMF and 15.8 g (140.7 mmol) of potassium tert-butoxide was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 2 h at 100 °C. After completion, a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added to the reaction mixture and the mixture was extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated to dryness. Yield of the crude (14): 7.2 g (23.1 mmol, 82%). Rf: 0.24 (B), 0.72 (C), 0.69 (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 7.80 (1H, d, H-6), 6.12 (1H, s, H-1'), 5.95 (1H, d, H-5), 4.80 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.10 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.04-3.82 (4H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-1''a, H-1''b), 1.55-1.51 (3H, 2d, CH3-All); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 174.68 (C-2), 162.62 (C-4), 140.08 (C-6), 128.78, 127.33 (All), 106.27 (C-5), 90.18 (C-1'), 89.14 (C-4'), 77.42 (C-2'), 76.31 (C-3'), 71.39 (C-5'), 56.34 (C-1''), 9.11 (CH3-All).

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-hydroxy-1-hydroxymethyl-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (15)

To derivative (14) (7.2 g, 23.1 mmol) was added 80 mL of 80% acetic acid and then kept at 100 °C for 4 h. After reaction completion, the acetic acid was evaporated and coevaporated three times with toluene. Yield of the crude (15): 6.3 g (23.1 mmol, 100%). Rf: 0.03 (B), 0.38 (C), (0.91) (D); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 7.84-7.79 (1H, d, H-6), 6.14 (1H, s, H-1'), 6.09 (1H, d, H-5), 4.69 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.43 (1H, s, H-3'), 4.16-3.70 (4H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b, H-1''a, H-1''b); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 176.87 (C-2), 162.69 (C-4), 140.33 (C-6), 106.04 (C-5), 90.30 (C-1'), 87.26 (C-4'), 77.42 (C-2'), 71.23 (C-3'), 71.05 (C-5'), 56.36 (C-1'').

Synthesis of (1S,3R,4R,7S)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-7-hydroxy-1-(4,4’-dimethoxytritylomethyl)-2,5-dioksabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (16)

The derivative (15) (6.3 g, 23.1 mmol) was coevaporated twice with 25 mL of anhydrous pyridine. The residue was dissolved in 80 mL of anhydrous pyridine and 4,4’-dimethoxytrityl chloride (11.7 g, 34.6 mmol) was added and left at room temperature for 2 h. After reaction completion, to the reaction mixture was added a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and extracted three times with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solution was evaporated, and coevaporated three times with toluene. The reaction mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using as solvent dichloromethane with gradually increasing amount of methanol (up to 5%). Yield of product (16): 10.2 g (17.8 mmol, 76.9%). Overall yield for the synthesis of protected LNA-2-thiouridine was 25.2%, which corresponds on average to 82% on each step. Rf: 0.35 (B), 0.46 (C); 1H NMR δH (CDCl3): 10.40 (1H, s, N-H), 8.14 (1H, d, H-6), 7.56-7.40 (9H, m, DMTr), 7.40-7.20 (4H, m, DMTr), 6.14 (1H, s, H-1'), 5.85 (1H, d, H-5), 4.73 (1H, s, H-2'), 4.24 (1H, s, H-3'), 3.90-3.80 (2H, m, H-1''a, H-1''b), 3.79 (6H, s, OCH3-DMTr), 3.60-3.49 (2H, m, H-5'a, H-5'b); 13C NMR δC (CDCl3): 174.52 (C-2), 159.89 (C-4), 158.78 (DMTr), 144.37 (DMTr), 140.29 (C-6), 130.07, 129.99, 128.62, 128.30, 127.97, 127.33, 127.22, 113.35 (DMTr), 106.26 (C-5), 90.12 (C-1'), 88.68 (DMTr), 87.02 (C-4'), 77.42 (C-2'), 71.35 (C-3'), 70.12 (C-5'), 57.57 (C-1''), 55.26 (OCH3).

Synthesis of (1R,3R,4R,7S)-7-(2-cyanoethoxy(diisopropylamino)phosphinoxy)-1-(4,4'-dimetoxytrityloxymethyl)-3-(2-thiouridine-1-yl)-2,5-dioxabicyclo[2.2.1]-heptane (17)

The compound (16) (3.65 g, 6.36 mmol) and tetrazole (0.45 g, 6.36 mmol) were dried under vacuum for several hours and dissolved in 43 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile. Then, to a stirred solution was added with syringe 2-cyanoethyl-N,N,N’,N’-tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite (2.47 g, 8.27 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h. A saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate was added and extracted 3 times with dichloromethane containing 1% of triethylamine. The organic phase was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using hexane containing 1% of triethylamine and gradually increasing ethyl acetate up to 75%. The fractions carrying product were combined and evaporated, and coevaporated three times with benzene and lyophilized to give product as a white solid material. Yield: 4.28 g (5.53 mmol, 86.9%). Rf: 0.45 (B), 0.58 (C); 31P NMR δC (DMSO-d6): 151.00, 148.26.

RESULTS

Synthesis of LNA-2-thiouridine

The chemical synthesis of LNA-2-thiouridine is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Two major problems were found when using standard procedures for synthesis of LNA nucleosides. First, trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate catalyzed condensation (36) of aglicone with silylated 2-thiouracil produced S-substituted nucleoside as major product (K. Pasternak, Z. Gdaniec, R. Kierzek – unpublished results). Changing temperature and solvent did not affect significantly those preferences. Tin chloride (IV) in 1,2-dichloroethane (37–39), however, provided ca. 90% N-substituted nucleosides (Figure 2). Second problem was removal of the transient protecting group from the 3'-hydroxyl. Classically, benzyl is removed by hydrogenolysis in presence of palladium catalyst (40). That and palladium free methods for deprotection of benzyl were insufficient for multigram scale of synthesis (40). Several alternative protecting groups, o-nitrobenzyl, tert-butyldimethylsilyl, methythiomethyl and 2-methoxyethoxymethyl (A. Kowalska, A. Pasternak, K. Pasternak, R. Kierzek – unpublished results) were found inapplicable for this synthesis. The allyl protection group, however, proved successful (Figure 1) (40–42).

Figure 1.

Scheme for synthesis of 1,2-di-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose, precursor of the aglicone for LNA-s2U preparation.

Figure 2.

Scheme for synthesis of 5'-O-dimethoxytrityl-LNA-s2U and it 3'-O-phosphoramidite.

The chemical synthesis of precursor of the ribose analogue was performed as described for standard synthesis but with allyl bromide replacement (12, 30, 40, 41). The allyl bromide reaction as well as all reactions toward synthesis of the precursor, 1,2-di-O-acetyl-3-O-allyl-5-O-methanosulfonyl-4-C-methanosulfonyloxymethyl-α-D-erytropentafuranose, was almost quantitative so column purification of the intermediates was omitted. The final product was purified by column chromatography and overall yield for 9 reactions was ca. 40% which means that the average reaction yield was ca. 90%.

Condensation of sugar precursor with silylated 2-thiouracil (ca. 1.3 equivalent) was performed at room temperature in 1,2-dichloroethane for 2 h in the presence of tin chloride (IV) (37). The reaction was complete and resulted in two products, N-glycoside (ca 90%) and S-glycoside (ca. 10%) (Figure 2). Because the character of the C-S bond in N- and S-glycosides differs, 13C NMR distinguished the character of the glycoside bond. The chemical shifts of C2 in N-glycoside and in S-glycoside were 175.72 and 164.45 ppm, respectively (43). Silica gel column purified N-glycoside only was used for the next reaction. The next reactions were performed according to the original procedure, except: in exchanging of 5'-O-methanosulfonyl, lithium benzoate was substituted for sodium benzoate due to solubility in DMF (12, 17, 30). A two-step deprotection was used for removal of 3'-O-allyl (44). In the first step, 3'-O-allyl with potassium tertbutoxide was converted into prop-1-enyl ether and deprotected with acetic acid. Overall yield for synthesis of protected LNA-2-thiouridine was over 25%, which corresponds on average to 82% for each step.

Design of sequences

To measure the effects of replacing 2'-O-methyluridine with 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-uridine with LNA-2-thiouridine in oligonucleotides, thermodynamics was measured for duplexes containing A-U and/or G-U pairs. Moreover, those base pairs were placed in terminal and internal positions within 2'-O-MeRNA/RNA duplexes.

Another group of model duplexes have 2'-O-methylated oligonucleotides containing a 3'-terminal pyrene residue. Pyrene at the 3'-end of a 2'-OMeRNA oligonucleotide enhances thermodynamic stability of 2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes by 2.2–2.4 kcal/mol, independent of RNA strand length and nature of the RNA nucleotide opposite the pyrene (45). This makes pyrene very useful for preparation of probes for isoenergetic RNA microarrays. LNA-2'-OMeRNA probes rich in A and U nucleotides often form only weak hybridization duplexes with target RNA. For this reason, it was important to evaluate the influence of LNA-2-thiouridine (s2UL) on the thermodynamic stability of 3'-pyrene terminated duplexes containing A-s2UL and G-s2UL. To make these studies more realistic, the RNA strand (mimic of RNA target) was two nucleotides longer than the 3'-pyrene terminated 2’-OMeRNA (mimic of microarray probe).

Influence of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine at 5'-terminal positions

The influence of 5'-terminal 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine on thermodynamic stabilities was studied in 2'-OMeRNA/RNA and chimeric LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes, 5'YCMUMAMCMCMAM/3'RGAUGGU. In those duplexes, the superscript M marks 2'-O-methylated nucleotides, Y means 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine (s2UM), LNA-2-thiouridine (s2UL), 2'-O-methyluridine (UM), or LNA-uridine (UL), R means A or G. The thermodynamic stabilities (ΔG°37) of 5'YCMUMAMCMCMAM/3'AGAUGGU were −7.18, −7.67, −7.64 and −8.51 kcal/mol for Y equal to UM, s2UM, UL and s2UL, respectively, whereas in duplexes 5'YCMUMAMCMCMAM/3'GGAUGGU, the thermodynamic stabilities were −6.79, −7.03, −7.01 and −7.45 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 1). Thus, 5'-terminal A-s2UM and A-s2UL base pairs enhance stability by 0.49 and 0.87 kcal/mol, respectively, relative to UM-A and UL-A, whereas 5'-terminal G-s2UM and G-s2UL base pairs enhance stabilities by 0.24 and 0.44 kcal/mol, respectively.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of helix formation with RNA and 2'-O-Me oligoribonucleotides. The effect of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine.a

| Average of curve fits | TM−1 vs log CT plots | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA duplexes | |||||||||||||

| (5'-3') | (3'-5') | −ΔH0 (kcal/mol) |

−ΔS0 (eu) |

−ΔG037 (kcal/mol) |

TMb (0C) |

−ΔH0 (kcal/mol) |

−ΔS0 (eu) |

−ΔG037 (kcal/mol) |

TMb (0C) |

ΔΔG037 (kcal/ mol) |

ΔTMb (0C) |

ΔΔG0,37c (kcal/ mol) |

ΔΔG037c (kcal/ mol) |

| UMCMUMAMCMCMAM, d | AGAUGGUd | 50.7±5.9 | 140.0±18.4 | 7.25±0.19 | 41.5 | 45.2±1.6 | 122.5±5.3 | 7.18±0.03 | 41.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| s2UMCMUMAMCMCMAM | AGAUGGU | 53.3±3.5 | 146.8±11.1 | 7.74±0.09 | 44.2 | 51.2±1.4 | 140.5±4.4 | 7.67±0.02 | 44.1 | −0.49 | 2.6 | −0.49 | 0 |

| UMCMUMAMCMCMAM | GGAUGGU | 47.2±5.1 | 130.4±16.6 | 6.74±0.14 | 38.4 | 42.0±0.8 | 113.6±2.5 | 6.79±0.01 | 39.0 | 0.39 | −2.5 | 0 | 0.39 |

| s2UMCMUMAMCMCMAM | GGAUGGU | (48.7 ±6.7) | (134.2±21.2) | (7.08±0.17) | (40.5) | (40.8±1.7) | (109.1±5.4) | (7.03±0.03) | (40.9) | (−0.24) | (−0.6) | (−0.24) | (0.64) |

| ULCMUMAMCMCMAM, d | AGAUGGUd | 55.7±3.3 | 154.4±10.0 | 7.84±0.19 | 44.4 | 47.2±3.0 | 127.5±9.6 | 7.64±0.08 | 44.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| s2ULCMUMAMCMCMAM | AGAUGGU | 58.8±3.2 | 161.7±9.9 | 8.65±0.13 | 48.6 | 53.9±1.7 | 146.6±5.2 | 8.51±0.05 | 48.8 | −0.87 | 4.3 | −0.87 | 0 |

| ULCMUMAMCMCMAM | GGAUGGU | 48.1±4.7 | 132.5±15.0 | 7.03±0.10 | 40.3 | 43.3±1.4 | 117.1±4.7 | 7.01±0.02 | 40.5 | 0.63 | −4.0 | 0 | 0.63 |

| s2ULCMUMAMCMCMAM | GGAUGGU | 47.9±8.7 | 130.2±27.6 | 7.55±0.16 | 43.7 | 44.2±4.4 | 118.6±14.2 | 7.45±0.18 | 43.6 | −0.44 | −0.9 | −0.44 | 1.06 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMUM, d | UGAUGGAd | 59.6±5.7 | 168.4±18.9 | 7.41±0.28 | 41.2 | 62.2±7.3 | 176.8±23.6 | 7.37±0.26 | 41.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMs2UM | UGAUGGA | 49.9±5.9 | 137.7±18.5 | 7.28±0.19 | 41.7 | 44.1±0.8 | 119.1±2.7 | 7.20±0.01 | 41.8 | 0.17 | 0.6 | 0.17 | 0 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMUM | UGAUGGG | 48.6±4.0 | 134.2±12.5 | 6.96±0.11 | 39.8 | 44.4±1.5 | 121.0±5.0 | 6.93±0.03 | 39.8 | 0.44 | −1.4 | 0 | 0.44 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMs2UM | UGAUGGG | 45.2±7.4 | 123.6±23.3 | 6.84±0.15 | 39.1 | 41.7±0.8 | 112.5±2.5 | 6.78±0.01 | 38.9 | 0.59 | −2.3 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMUL, d | UGAUGGAd | 59.2±5.2 | 167.7±17.2 | 7.19±0.17 | 40.5 | 55.6±2.6 | 155.8±8.5 | 7.24±0.04 | 41.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMs2UL | UGAUGGA | 54.5±3.3 | 150.3±10.3 | 7.92±0.15 | 45.1 | 48.4±1.2 | 130.9±3.9 | 7.84±0.02 | 45.6 | −0.60 | 4.6 | −0.60 | 0 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMUL, d | UGAUGGGd | 57.6±11.2 | 161.3±35.9 | 7.52±0.29 | 42.4 | 58.4±9.0 | 164.6±29.0 | 7.38±0.38 | 41.6 | −0.14 | 0.6 | 0 | −0.14 |

| AMCMUMAMCMCMs2UL | UGAUGGG | 50.6±3.1 | 139.3±9.5 | 7.44±0.16 | 42.7 | 44.7±1.9 | 120.4±6.2 | 7.40±0.33 | 43.1 | −0.02 | 2.1 | −0.02 | 0.44 |

| AMCMUMUMGMCMAM | UGAACGU | 61.2±3.3 | 172.4±10.0 | 7.71±0.15 | 43.1 | 52.7±0.7 | 145.3±2.3 | 7.59±0.01 | 43.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMCMUMs2UMGMCMAM | UGAACGU | 60.9±5.3 | 167.4±16.3 | 8.97±0.22 | 50.0 | 62.4±5.2 | 172.4±16.3 | 9.00±0.17 | 49.8 | −1.41 | 6.4 | −1.41 | 0 |

| AMCMUMUMGMCMAM, d | UGAGCGUd | 62.5±4.1 | 186.3±13.5 | 4.76±0.17 | 28.4 | 66.4±11.1 | 199.2±37.2 | 4.60±0.58 | 28.2 | 2.99 | −15.2 | 0 | 2.99 |

| AMCMUMs2UMGMCMAM | UGAGCGU | 46.2±2.8 | 132.2±9.4 | 5.16±0.16 | 28.1 | 46.6±1.8 | 133.7±6.1 | 5.17±0.09 | 28.2 | 2.42 | −15.2 | −0.57 | 3.83 |

| AMCMUMULGMCMAM, d | UGAACGUd | 61.0±2.3 | 167.7±7.4 | 9.00±0.12 | 50.1 | 59.5±1.6 | 163.1±5.0 | 8.96±0.05 | 50.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMCMUMs2ULGMCMAM | UGAACGU | 59.6±7.0 | 158.3±21.1 | 10.48±0.43 | 59.0 | 59.1±1.4 | 157.0±4.2 | 10.40±0.07 | 58.7 | −1.44 | 8.5 | −1.44 | 0 |

| AMCMUMULGMCMAM, d | UGAGCGUd | 60.8±11.0 | 174.2±35.5 | 6.78±0.19 | 38.3 | 55.9±4.7 | 158.3±15.5 | 6.76±0.13 | 38.3 | 2.20 | −11.9 | 0 | 2.20 |

| AMCMUMs2ULGMCMAM | UGAGCGU | 35.2±3.6 | 91.9±11.3 | 6.71±0.18 | 38.6 | 38.7±5.8 | 103.3±18.8 | 6.64±0.31 | 37.9 | 2.32 | −12.3 | 0.12 | 3.76 |

| GMUMUMAMCMCMAM | CAAUGGU | 55.3±3.5 | 156.0±11.1 | 6.88±0.10 | 39.0 | 49.9±1.2 | 138.6±3.9 | 6.85±0.01 | 39.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GMs2UMUMAMCMCMAM | CAAUGGU | 54.2±3.8 | 150.4±11.8 | 7.60±0.13 | 43.2 | 48.8±0.7 | 133.1±2.3 | 7.51±0.01 | 43.4 | −0.66 | 4.4 | −0.66 | 0 |

| GMUMUMAMCMCMAM | CGAUGGU | 47.4±4.4 | 136.8±14.4 | 4.97±0.17 | 27.1 | 45.8±4.8 | 131.5±16.3 | 5.06±0.27 | 27.3 | 1.79 | −11.7 | 0 | 1.79 |

| GMs2UMUMAMCMCMAM | CGAUGGU | 41.8±5.2 | 119.6±17.3 | 4.71±0.34 | 24.1 | 41.5±5.3 | 118.3±17.9 | 4.76±0.39 | 24.3 | 2.09 | −14.7 | 0.30 | 2.75 |

| GMULUMAMCMCMAM | CAAUGGU | 58.4±3.1 | 161.6±9.4 | 8.27±0.16 | 46.5 | 53.7±2.0 | 146.7±6.4 | 8.15±0.05 | 46.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GMs2ULUMAMCMCMAM | CAAUGGU | 55.2±3.7 | 149.6±11.3 | 8.82±0.22 | 50.4 | 50.9±1.1 | 136.3±3.6 | 8.67±0.03 | 50.6 | −0.52 | 3.9 | −0.52 | 0 |

| GMULUMAMCMCMAM | CGAUGGU | 51.7±3.1 | 146.4±9.8 | 6.29±0.16 | 35.5 | 47.0±2.4 | 131.1±8.0 | 6.35±0.06 | 35.8 | 1.80 | −10.9 | 0 | 1.80 |

| GMs2ULUMAMCMCMAM | CGAUGGU | 41.7±2.9 | 115.1±9.2 | 5.98±0.08 | 33.0 | 40.1±1.4 | 109.9±4.6 | 6.01±0.05 | 33.0 | 2.14 | −13.7 | 0.34 | 2.66 |

solutions are 1 M NaCl, 20 mmol sodium cacodylate and 0.5 mmol Na2EDTA, pH 7,

calculated for 10−4 M total strand concentration,

data with the same character of fonts belong to the same set,

data from ref. 16. The data in parenthesis indicate non–two state melting.

For 3'-pyrene terminated duplexes, 5'YGMUMGMUMpyrene/3'GACACAG, the thermodynamic stability was −7.35 and −8.12 kcal/mol for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively. The enhancement of duplex stability (ΔΔG°37) due to replacement of 2-oxo with 2-thio analogues was 0.77 kcal/mol in an A-U pair. When UL and s2UL pair with G in 5'YGMUMGMUMpyrene/3'GGCACAG duplexes, the free energies were −5.68 and −6.12 kcal/mol for the same modified nucleotides, so the increase of the stability was 0.44 kcal/mol.

Influence of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine at 3'-terminal positions

The effects of 3'-terminal s2UM and s2UL were studied in duplexes, 5'AMCMUMAMCMCMY/3'UGAUGGA. The thermodynamic stabilities were −7.37, −7.20, −7.24, and −7.84 kcal/mol for Y equal to UM, s2UM, UL, and s2UL, respectively (Table 1). When 2-thio modified nucleotides base paired to G in 5'AMCMUMAMCMCMY/3'UGAUGGG, the thermodynamic stabilities were −6.93, −6.78, −7.38, and −7.40 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 1). The presence of a 3'-terminal A-s2UM base pair diminished stability by 0.17 kcal/mol whereas a 3'-terminal A-s2UL enhanced stability by 0.60 kcal/mol relative to 3’-terminal A-UM and A-UL, respectively. The 3'-terminal base pairs, G-s2UM and G-s2UL, change the thermodynamic stability by 0.15 and −0.02 kcal/mol, respectively, relative to G-UM and G-UL.

When s2UL and 3'-terminal pyrene were placed next to each other in the duplexes 5'UMGMUMGMYpyrene/3'GACACAG, the stabilities were −7.03 and −7.54 kcal/mol, for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively (Table 2). Thus, the stability (ΔΔG°37) of duplex increased by 0.51 kcal/mol due to the replacement of uridine with 2-thiouridine in an A-U pair. When UL and s2UL base pair with G in 5'UMGMUMGMYpyrene/3'GACACGG, the free energies were −6.42 and −6.25 kcal/mol for the same modified nucleotides, so stability was diminished by 0.17 kcal/mol (Table 2).

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters of helix formation with RNA and 2'-O-Me oligoribonucleotides. The effect of LNA-2-thiouridine in the presence of 3'-pyrenea

| Average of curve fits | TM−1 vs log CT plots | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA duplexes | |||||||||||||

| (5'-3') | (3'-5') | −ΔH0 (kcal/mol) |

−ΔS0 (eu) |

−ΔG037 (kcal/mol) |

TMb (0C) |

−ΔH0 (kcal/mol) |

−ΔS0 (eu) |

−ΔG037 (kcal/mol) |

TMb (0C) |

ΔΔG037 (kcal/mol) |

ΔTMb (0C) |

ΔΔG037c (kcal/mol) |

ΔΔG037c (kcal/mol) |

| ULGMUMGMUM pyrene | GACACAG | 48.6±3.1 | 133.0±9.9 | 7.37±0.10 | 42.4 | 43.9±1.6 | 117.8±5.2 | 7.35±0.02 | 42.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| s2ULGMUMGMUMpyrene | GACACAG | 47.9±2.1 | 128.0±6.6 | 8.20±0.08 | 48.2 | 46.0±1.1 | 122.0±3.5 | 8.12±0.03 | 48.1 | −0.77 | 5.2 | −0.77 | 0 |

| ULGMUMGMUMpyrene | GGCACAG | 38.2±3.1 | 104.9±10.3 | 5.67±0.10 | 30.2 | 38.8±2.2 | 106.7±7.6 | 5.68±0.11 | 30.3 | 1.67 | −12.6 | 0 | 1.67 |

| s2ULGMUMGMUMpyrene | GGCACAG | 35.7±8.9 | 94.9±30.3 | 6.28±0.61 | 34.8 | 36.9±4.2 | 99.3±13.8 | 6.12±0.24 | 33.6 | 1.23 | −9.3 | −0.44 | 2.00 |

| UMGMUMGMULpyrene | GACACAG | 41.6±2.9 | 111.3±9.1 | 7.05±0.10 | 40.9 | 41.8±2.3 | 112.1±7.4 | 7.03±0.05 | 40.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UMGMUMGMs2ULpyrene | GACACAG | 44.0±2.3 | 117.4±7.2 | 7.60±0.13 | 44.7 | 40.0±0.6 | 104.7±2.0 | 7.54±0.01 | 45.0 | −0.51 | 4.3 | −0.51 | 0 |

| UMGMUMGMULpyrene | GACACGG | 44.3±2.2 | 122.4±7.1 | 6.33±0.09 | 35.6 | 40.3±1.5 | 109.3±5.1 | 6.42±0.05 | 36.1 | 0.61 | −4.6 | 0 | 0.61 |

| UMGMUMGMs2ULpyrene | GACACGG | 42.3±5.0 | 115.8±16.3 | 6.37±0.17 | 35.8 | 47.7±2.1 | 133.6±7.0 | 6.25±0.06 | 35.2 | 0.78 | −5.5 | 0.17 | 1.29 |

| CMUMULGMCMpyrene | UGAACGU | 54.8±5.9 | 145.4±17.9 | 9.71±0.32 | 56.1 | 51.1±1.2 | 134.2±3.7 | 9.52±0.06 | 56.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CMUMs2ULGMCMpyrene | UGAACGU | 57.7±4.0 | 150.5±11.7 | 11.05±0.34 | 63.4 | 57.0±3.2 | 148.5±9.5 | 10.97±0.23 | 63.2 | −1.45 | 6.9 | −1.45 | 0 |

| CMUMULGMCMpyrene | UGAGCGU | 48.9±2.6 | 134.4±8.3 | 7.20±0.10 | 41.3 | 45.6±1.1 | 124.1±3.4 | 7.18±0.01 | 41.5 | 2.34 | −14.8 | 0 | 2.34 |

| CMUMs2ULGMCMpyrene | UGAGCGU | 34.0±4.0 | 85.4±12.1 | 7.51±0.38 | 46.2 | 34.2±5.7 | 86.1±18.2 | 7.49±0.45 | 46.0 | 2.03 | −10.3 | −0.31 | 3.48 |

| UMGMULGMUM pyrene | GACACAG | 47.0±2.8 | 125.8±8.6 | 7.97±0.13 | 46.8 | 43.0±1.3 | 113.2±4.2 | 7.90±0.02 | 47.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UMGMs2ULGMUMpyrene | GACACAG | 49.3±6.1 | 130.2±18.8 | 8.88±0.28 | 52.5 | 49.6±3.9 | 131.2±12.1 | 8.87±0.16 | 52.3 | −0.97 | 5.1 | −0.97 | 0 |

| UMGMULGMUMpyrene | GACGCAG | 43.0±5.2 | 120.7±17.3 | 5.57±0.21 | 30.2 | 44.4±2.7 | 125.2±9.0 | 5.59±0.11 | 30.6 | 2.31 | −16.6 | 0 | 2.31 |

| UMGMs2ULGMUMpyrene | GACGCAG | 42.3±5.8 | 117.9±19.9 | 5.76±0.42 | 31.4 | 44.1±6.5 | 124.0±21.7 | 5.66±0.41 | 31.0 | 2.24 | 16.2 | −0.07 | 3.21 |

| UMGMULGMULpyrene | GACACAG | 45.8±1.4 | 119.6±4.4 | 8.75±0.08 | 52.8 | 45.0±0.9 | 117.1±2.8 | 8.71±0.03 | 52.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UMGMs2ULGMs2ULpyrene | GACACAG | 49.3±4.0 | 126.3±12.1 | 10.10±0.29 | 61.2 | 50.1±2.2 | 128.8±6.7 | 10.12±0.13 | 60.9 | −1.41 | 8.1 | −1.41 | 0 |

| UMGMULGMULpyrene | GACGCGG | 53.4±4.8 | 152.4±15.9 | 6.14±0.17 | 34.7 | 50.8±2.9 | 144.0±9.4 | 6.21±0.07 | 35.0 | 2.50 | −17.8 | 0 | 2.50 |

| UMGMs2ULGMs2ULpyrene | GACGCGG | 44.2±4.9 | 115.5±15.0 | 8.36±0.28 | 50.4 | 43.3±5.3 | 113.0±16.3 | 8.28±0.31 | 50.1 | 0.43 | −2.7 | −2.07 | 1.84 |

| CMULAMULCMpyrene | UGAUAGU | 54.9±2.5 | 148.6±7.6 | 8.83±0.14 | 50.6 | 55.8±2.8 | 151.5±8.8 | 8.85±0.10 | 50.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene | UGAUAGU | 53.1±3.3 | 138.4±9.9 | 10.19±0.23 | 60.0 | 51.1±2.0 | 132.3±6.2 | 10.03±0.12 | 59.8 | −1.18 | 9.3 | −1.18 | 0 |

| CMULAMULCMpyrene | UGGUGGU | 48.5±6.3 | 142.3±21.2 | 4.37±0.27 | 23.8 | 44.6±5.3 | 129.2±18.1 | 4.57±0.36 | 24.0 | 4.28 | −26.5 | 0 | 4.28 |

| CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene | UGGUGGU | 25.4±5.1 | 61.0±17.1 | 6.51±0.69 | 36.7 | 28.4±11.6 | 70.6±37.2 | 6.55±1.76 | 37.2 | 2.30 | −13.3 | −1.98 | 3.48 |

| CMULAMULCMpyrene | UGAUGGU | 48.4±4.3 | 133.8±13.7 | 6.94±0.12 | 39.7 | 47.5±2.5 | 130.6±8.3 | 6.95±0.06 | 39.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene | UGAUGGU | 40.7±2.5 | 109.5±8.1 | 6.74±0.10 | 38.6 | 41.3±1.6 | 111.6±5.2 | 6.70±0.04 | 38.3 | 0.25 | −1.4 | 0.25 | 0 |

| CMULAMULCMpyrene | UGGUAGU | 47.0±4.6 | 132.1±15.2 | 6.02±0.19 | 33.6 | 45.5±3.4 | 127.1±11.2 | 6.08±0.13 | 34.0 | 0.87 | −5.7 | 0 | 0.87 |

| CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene | UGGUAGU | 38.7±4.8 | 105.3±15.5 | 6.06±0.15 | 33.3 | 41.2±5.7 | 113.3±18.6 | 6.03±0.29 | 33.3 | 0.92 | −6.4 | 0.05 | 0.67 |

solutions are 1 M NaCl, 20 mmol sodium cacodylate and 0.5 mmol Na2EDTA, pH 7,

calculated for 10−4 M oligomer concentration,

the date with the same character of fonts belong to the same set.

Influence of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine at internal positions

The s2UM and s2UL nucleotides were placed at two internal positions, the central and 5'-penultimate, positions within 2'-OMeRNA/RNA and LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes (Table 1). At the center of 5'AMCMUMYGMCMAM/3'UGAACGU duplexes, the thermodynamic stabilities were −7.59, −9.00, −8.96 and −10.40 kcal/mol for Y equal to UM, s2UM, UL, and s2UL, respectively. When those nucleotides base paired to G, in 5'AMCMUMYGMCMAM/3'UGAGCGU, the thermodynamic stabilities were −4.60, −5.17, −6.76 and −6.64 kcal/mol, respectively. Thus, replacement of UM with s2UM or UL with s2UL enhanced the duplex thermodynamic stability (ΔΔG°37) by 1.41 and 1.44 kcal/mol, respectively, when base pairing to A, whereas the changes when base pairing to G were −0.57 and 0.12 kcal/mol, respectively.

Two sets of LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes with a 3'-terminal pyrene were investigated. For 5'CMUMYGMCMpyrene/3'UGAACGU, the thermodynamic stabilities were −9.52 and −10.97 kcal/mol, for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively. The enhancement of the A-U pair stability (ΔΔG°37) was 1.45 kcal/mol. When binding of the oligonucleotides occurred via mismatch to G the stabilities of duplexes, 5'CMUMYGMCMpyrene/3'UGAGCGU were −7.18 and −7.49 kcal/mol, respectively. In that case, the replacement of UL with s2UL increased stability by only 0.31 kcal/mol. In the second set of the duplexes, 5'UMGMYGMUMpyrene/3'UACACAU, the stabilities were −7.90 and −8.87 kcal/mol for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively, so enhancement of A-U pair stability (ΔΔG°37) was 0.97 kcal/mol. When UL and s2UL paired to G in 5'UMGMYGMUMpyrene/3'UACGCAU, free energies of the duplexes were −5.59 and −5.66 kcal/mol, respectively, so enhancement was only 0.07 kcal/mol.

Placing of s2UM and s2UL at the 5'-penultimate position within 5'GMYUMAMCMCMAM/3'CRAUGGU duplexes resulted in a similar range of thermodynamic stability changes. For 5'GMYUMAMCMCMAM/3'CAAUGGU duplexes, the thermodynamic stabilities were −6.85, −7.51, −8.15, and −8.67 kcal/mol for Y equal to UM, s2UM, UL and s2UL, respectively. When the same nucleotides paired with G in duplexes, 5'GMYUMAMCMCMAM/3'CGAUGGU, the thermodynamic stabilities were −5.06, −4.76, −6.35 and −6.01 kcal/mol, respectively. Thus, replacing UM with s2UM and UL with s2UL enhanced A-U base pair interaction by 0.66 and 0.52 kcal/mol, respectively, but diminished G-U pair interaction by 0.30 and 0.33 kcal/mol, respectively.

Influence of multiple substitutions of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-2-thiouridine at internal positions

It is often proposed to place more than one s2UL within the same duplex. Thus, several 5'UMGMYGMYpyrene/3'GACRCRG and 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGRURGU duplexes were studied (Table 2).

In the set of 5'UMGMYGMYpyrene/3'GACACAG duplexes, the thermodynamic stabilities were −8.71 and −10.12 kcal/mol, for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively, so the enhancement (ΔΔG°37) due to presence of 2-thio derivatives was 1.41 kcal/mol for two A-U pairs. For the duplexes, 5'UMGMYGMYpyrene/3'GACGCGG, with two G-U pairs the free energies were −6.21 and −8.28 kcal/mol, respectively, so stability was enhanced by 2.07 kcal/mol. For the set of duplexes, 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGAUAGU, the thermodynamic stabilities were −8.85 and −10.03 kcal/mol for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively. The increase in stability was equal to 1.18 kcal/mol for two A-U pairs. For the duplexes, 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGGUGGU, the free energies were −4.57 and −6.55 kcal/mol, respectively, so stability was increased by 1.98 kcal/mol. The ΔH° values for 5'CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene/3'UGGUGGU, however, are small which indicates unusual melting.

Finally, the duplexes, 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGRURGU, were designed so that one Y pairs with A and the other Y pairs with G. The thermodynamic stabilities of 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGAUGGU were −6.95 and −6.70 kcal/mol for Y equal to UL and s2UL, respectively, so replacement of UL with s2UL destabilized the duplex by 0.25 kcal/mol. When positions of matched and mismatched base pairs were inverted to give 5'CMYAMYCMpyrene/3'UGGUAGU, the free energies were −6.08 and −6.03 kcal/mol, so there was negligible difference in the thermodynamic stability.

DISCUSSION

The 2-thio modified RNA nucleotides are relatively common in tRNA and important for biological functions (1, 6, 7, 9, 10, 46, 47). The presence of a sulfur instead of oxygen at position 2 of a pyrimidine residue results in predominantly C3'-endo ribose conformation (2, 3), and an increase of thermodynamic stabilities of complementary duplexes (4, 48–50)

A 2-thiouridine within an oligoribonucleotide enhances matched binding to A but diminishes mismatched binding to G in a target RNA (4, 48, 49). In RNA, the thermodynamic stability of unmodified A-U and G-U base pairs are very similar, so replacing U with s2U increases selectivity of binding (4). This is also observed with 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine (43, 48, 49). LNA forms thermodynamically very stable duplexes with RNA, 2'-OMeRNA and DNA strands (12, 16–18, 51, 52). Thus, it is potentially useful for incorporation in probes and therapeutics (14, 19–22, 53–56). For various applications, additional modifications of LNA nucleosides have been introduced (56–60). Many applications would benefit from enhanced specificity for binding A over G, which led us to develop a chemical synthesis of LNA-2-thiouridine.

To measure the influence of s2UL on thermodynamic stabilities, several LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes were studied. For comparison, isosequential duplexes carrying 2'-O-methyluridine, 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and LNA-uridine were measured to evaluate the effects of 2-thio and LNA substitution on thermodynamic stability and selectivity of base pairing.

The position of a modified nucleotide within a duplex affects its thermodynamic stability (16, 17, 61). For this reason, s2UM and s2UL were placed at 5'- and 3'-terminal, central internal, and 5'-penultimate positions in primarily 2'-O-methyl oligonucleotdides. Thermodynamic properties of 2'-O-methylated oligonucleotides with 3'-terminal pyrene were also studied (45). Both types of oligonucleotides are useful for isoenergetic microarrays (19–23).

The influence of LNA rings on enhancement of the thermodynamic stabilities of 2-thiouracil nucleotides

LNA ribose enforces C3'-endo conformation and enhances the thermodynamic stability of RNA, 2'-OMeRNA and DNA duplexes (12, 13). Stacking and single strand pre-organization is mostly responsible for this enhancement of thermodynamic stability (52, 62). The increase of thermodynamic stability with s2UL is also dependent on position within the duplex. The largest increase was found at internal positions whereas shifting the LNA nucleotide to the end of a duplex resulted in less enhancement of thermodynamic stability. For the LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes studied here, changing 2'-O-methylribose to LNA enhanced duplex stability by 0.84, 0.64, 1.40, and 1.16 kcal/mol, for A-s2UL present at 5'-terminal, 3'-terminal, central, and 5'-penultimate positions, respectively (Table 1). This compares with the average enhancements for LNA vs. 2'-OMe of 0.53, 0.14, and 1.28 kcal/mol for 5'-terminal, 3'-terminal, and internal positions, respectively (16).

The influence of 2-thiouracil nucleotide on the selectivity of binding to adenosine and guanosine in a complementary RNA strand

A major goal is to enhance selectivity for binding of uridine to adenosine over guanosine. Previous studies showed that 2-thiouridine provides greater selectivity than U (4). For RNA/RNA duplexes with U at the central position, the difference between A-U and G-U increased by 1.45 kcal/mol when A-s2U and G-s2U substitutions were made. This corresponded to an increase of 8.0 °C in the difference between melting temperatures (4). Sekine et al. reported that replacing U with s2U and s2UM in RNA duplexes increased the difference in melting temperature by 10.8 and 11.8 °C, respectively (48). When the same RNA strands were bound to a DNA strand, the increases in melting temperature were 7.3 and 11.2 °C due to replacement of U with s2U and s2UM, respectively. That suggested that changing 2'-O-methylribose to LNA ring would further increase A-U over G-U binding selectivity (48).

The enhancement of the selectivity [(ΔΔΔG°37 (A-s2UM) - (G-s2UM)] of s2UM over UM binding was equal to 0.25. 0.42, 0.84 and 0.96 kcal/mol for 5'-terminal, 3'-terminal, central, and 5'-penultimate positions, respectively (Table 3). Replacement of UM with s2UL increased the selectivity of binding to A over G [(ΔΔΔG°37 (A-s2UL) - (G-s2UL)] by 0.67, 0.00, 0.77 and 0.87 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 3). Substitution of s2UL for s2UM at the central position has little effect on selectivity but a large affect on thermodynamic stability (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in free energies (ΔG°37 in kcal/mol) resulting from substitution of UM to s2UM, UM to s2UL and UL to s2UL at particular positions within 2'-OMeRNA/RNA and LNA-2'-OMeRNA/RNA duplexes.

| 5'-Terminal | 3'-Terminal | Central | 5'-Penultimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM→s2UM (UM→UL) |

UM→s2UL | UL→s2UL | UM→s2UM (UM→UL) |

UM→s2UL | UL→s2UL | UM→s2UM (UM→UL) |

UM→s2UL | UL→s2UL | UM→s2UM (UM→UL) |

UM→s2UL | UL→s2UL | |

| ΔΔG°37 A-Y | −0.99 (−0.46) |

−1.33 | −0.87 | 0.17 (0.13) |

−0.47 | −0.60 | −1.41 (−1.37) |

−2.81 | −1.44 | −0.66 (−1.30) |

−1.82 | −0.52 |

| ΔΔG°37 G-Y | −0.24 (−0.22) |

−0.66 | −0.44 | 0.59 (−0.45) |

−0.47 | −0.02 | −0.57 (−2.16) |

−2.04 | 0.12 | 0.30 (−1.29) |

−0.95 | 0.34 |

| ΔΔΔG°37 (A-Y) – (G-Y) |

−0.25 (−0.24) |

−0.67 | −0.43 | −0.42 (0.58) |

0.00 | −0.58 | −0.84 (0.79) |

−0.77 | −1.56 | −0.96 (−0.01) |

−0.87 | −0.86 |

For LNA-2'-OMeRNApyrene/RNA duplexes, the enhancement of selectivity for binding of UL versus s2UL to A versus G [ΔΔΔG°37 (A-s2UL) - (G-s2UL)] was equal to 0.33, 0.68, 1.14 and 0.90 kcal/mol for 5'- and 3'-terminal, and two central positions, respectively (Table 4). Thus, replacement of 2-oxo with 2-thio nucleotide improved selectivity most strongly at internal positions within the duplex. Surprisingly, LNA-2'-OMeRNApyrene/RNA duplexes with double substitution of UL with s2UL provided less specificity than duplexes with UL (Table 4). It could be because an LNA nucleotide enforces its 3'-adjacent nucleotide to adopt predominantly C3'-endo conformation as well. The differences in electronegativity between sulfur and oxygen (one unit) could result in different stacking interactions of A-UL and G-UL in comparison to A-s2UL and G-s2UL, in both single strand and duplex.

Table 4.

Differences in free energies (ΔG°37) resulting from substitution of UL to s2UL at particular positions within LNA-2'-OMeRNApyrene/RNA duplexes.

| 5'-Terminal | 3'-Terminal | Central 1 | Central 2 | Doubles 2UL (1)a |

Double s2UL (2)b |

Mixed substitutions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΔG°37 A-s2UL | −0.77 | −0.51 | −1.45 | −0.97 | −1.41 | −1.18 | 0.25d |

| ΔΔG°37 G-s2UL | −0.44 | 0.17 | −0.31 | −0.07 | −2.07 | (−1.98)c | 0.05e |

| ΔΔΔG°37 (A-s2UL) – (G-s2UL) |

−0.33 | −0.68 | −1.14 | −0.90 | 0.66 | 0.80 |

sequences are 5'UMGMs2ULGMs2ULpyrene/3'GACRCRG,

sequences are 5'CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene/3'UGRURGU,

values of ΔH° for 5'CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene/3'UGGUGGU are unusually small,

sequence is 5'CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene/3'UGAUGGU,

sequence is 5'CMs2ULAMs2ULCMpyrene/3'UGGUAGU.

The effects of 2-thiouracil and LNA substitution are not always additive

Table 3 gives the differences in ΔG°37 for substituting s2UM for UM, UL for UM (in parenthesis), and s2UL for UM. In most but not all cases, the sum of the effects of the first two substitutions is close to the effect of the latter substitution. This is least true at the 3'-terminal and central positions.

Recommendations for probe design

Thermodynamic stability and specificity are important considerations when designing probes and therapeutics. Uridine provides both low stability and specificity, but modifications can enhance both characteristics. Previous work has shown that UM to UL substitution has a large effect on stability when inside a duplex (16, 17). Moreover, UM to UL substitutions anywhere have either negligible or negative effect on specificity for A-U vs. G-U (4, 16). The summaries in Table 3 and Table 4 provide insight into optimal design of probes with s2U. Substitution of U with s2U is most effective at enhancing both stability and specificity when a single substitution is inside the duplex. The maximum observed enhancements in binding and specificity from substituting s2UL for UM were −2.81 and −0.87 kcal/mol, respectively, which at 37 °C corresponds to more than 90 and 4-fold improvements, respectively, in binding constant and relative binding to A-U vs. G-U. The maximum observed enhancements from substitution of s2UM for UM were −1.41 and −0.96 kcal/mol, respectively. Significant enhancements in both binding (−1.33 kcal/mol) and A-U vs. G-U specificity (−0.67 kcal/mol) were also observed for substituting s2UL for UM at the 5’-terminal position. Substitution of s2UL for UM at the 3'-terminal position, however, does not appear to be advantageous (Table 3). Adding pyrene to the 3'-end, however, does provide large discrimination (−1.29 kcal/mol) between A-U and G-U pairs by an adjacent s2UL (Table 2). These generalizations are based on the limited number of sequences studied, but are consistent with expectation from studies of UM and UL in a larger number of sequence contexts (16, 17, 45). A surprising result, however, is that two s2UL for UL substitutions reduce specificity for A-U vs. G-U pairs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education, grant NN 3013383 33 to E.K. and grant PBZ-MNiSW-07/I/2007 to R.K and by National Institute of Health grant GM 22939 to D.H.T.

RFERENCES

- 1.Limbach PA, Crain PF, McCloskey JA. The modified nucleosides of RNA - summary. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2183–2196. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agris PF, Sierzputowska-Gracz H, Smith W, Malkiewicz A, Sochacka E, Nawrot B. Thiolation of uridine carbon-2 restricts the motional dynamics of the transfer-RNA wobble position nucleoside. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:2652–2656. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar RK, Davis DR. Synthesis and studies on the effect of 2-thiouridine and 4-thiouridine on sugar conformation and RNA duplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1272–1280. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testa SM, Disney MD, Turner DH, Kierzek R. Thermodynamics of RNA-RNA duplexes with 2- or 4-thiouridines: Implications for antisense design and targeting a group I intron. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16655–16662. doi: 10.1021/bi991187d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto I, Selo K, Sekine M. Triplex forming ability of oligonucleotides containing 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine or 2-thiothymidine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3334–3336. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ishii N, Ohta S, Watanabe K. Wobble modification defect in tRNA disturbs codon-anticodon interaction in a mitochondrial disease. EMBO J. 2001;20:4794–4802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy FV, Ramakrishnan V, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys) UUU. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:1186–1191. doi: 10.1038/nsmb861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dao V, Guenther R, Malkiewicz A, Nawrot B, Sochacka E, Kraszewski A, Jankowska J, Everett K, Agris PF. Ribosome binding of DNA analogs of transfer-RNA requires base modifications and supports the extended anticodon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S.A. 1994;91:2125–2129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashraf SS, Sochacka E, Cain R, Guenther R, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. Single atom modification (O -> S) of tRNA confers ribosome binding. RNA. 1999;5:188–194. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agris PF, Guenther R, Ingram PC, Basti MM, Stuart JW, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz A. Unconventional structure of tRNA(Lys)SUU anticodon explains tRNA's role in bacterial and mammalian ribosomal frameshifting and primer selection by HIV-1. RNA. 1997;3:420–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sipa K, Sochacka E, Kazmierczak-Baranska J, Maszewska M, Janicka M, Nowak G, Nawrot B. Effect of base modifications on structure, thermodynamic stability, and gene silencing activity of short interfering RNA. RNA. 2007;13:1301–1316. doi: 10.1261/rna.538907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koshkin AA, Singh SK, Nielsen P, Rajwanshi VK, Kumar R, Meldgaard M, Olsen CE, Wengel J. LNA (Locked Nucleic Acids): Synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation, and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3607–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obika S, Nanbu D, Hari Y, Morio K, In Y, Ishida T, Imanishi T. Synthesis of 2'-O,4'-C-methyleneuridine and -cytidine. Novel bicyclic nucleosides having a fixed C-3'-endo sugar puckering. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:8735–8738. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wengel J, Petersen M, Frieden M, Koch T. Chemistry of locked nucleic acids (LNA): Design, synthesis, and biophysical properties. Lett. Pept. Sci. 2003;10:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur H, Wengel J, Maiti S. Thermodynamics of DNA-RNA heteroduplex formation: Effects of locked nucleic acid nucleotides incorporated into the DNA strand. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1218–1227. doi: 10.1021/bi700996z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kierzek E, Ciesielska A, Pasternak K, Mathews DH, Turner DH, Kierzek R. The influence of locked nucleic acid residues on the thermodynamic properties of 2'-O-methyl RNA/RNA heteroduplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5082–5093. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasternak A, Kierzek E, Pasternak K, Turner DH, Kierzek R. A chemical synthesis of LNA-2,6-diaminopurine riboside, and the influence of 2'-O-methyl-2,6-diaminopurine and LNA-2,6-diaminopurine ribosides on the thermodynamic properties of 2'-O-methyl RNA/RNA heteroduplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4055–4063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McTigue PM, Peterson RJ, Kahn JD. Sequence-dependent thermodynamic parameters; for locked nucleic acid (LNA)-DNA duplex formation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5388–5405. doi: 10.1021/bi035976d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kierzek E, Barciszewska MZ, Barciszewski J. Isoenergetic microarray mapping reveals differences in structure between tRNAiMet and tRNAmMet from Lupinus luteus. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 2008;52:215–216. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kierzek E, Christensen SM, Eickbush TH, Kierzek R, Turner DH, Moss WN. Secondary structures for 5' regions of R2 retrotranspozon RNAs reveal a novel conserved pseudoknot and regions that evolve under different constraints. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;390:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenek M, Kierzek E. Isoenergetic microarray mapping - the advantage of this method in studying the structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNAPhe. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 2008;52:219–220. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kierzek E, Fratczak A, Pasternak A, Turner DH, Kierzek R. 2nd European Conference on Chemistry for Life Sciences, Wroclaw. Bologna, Italy: Medimond, International Proceedings Division; 2007. Isoenergetic RNA microarrays, a new method to study the structure and interactions of RNA; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kierzek E, Kierzek R, Moss WN, Christensen SM, Eickbush TH, Turner DH. Isoenergetic penta- and hexanucleotide microarray probing and chemical mapping provide a secondary structure model for an RNA element orchestrating R2 retrotransposon protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1770–1782. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kierzek E, Kierzek R, Turner DH, Catrina IE. Facilitating RNA structure prediction with microarrays. Biochemistry. 2006;45:581–593. doi: 10.1021/bi051409+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majlessi M, Nelson NC, Becker MM. Advantages of 2'-O-methyl oligoribonucleotide probes for detecting RNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2224–2229. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson HE, Belsham GJ, Sproat BS, Hentze MW. Target-specific arrest of messenger-RNA translation by antisense 2'-O-alkyloligoribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4591–4598. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tallet-Lopez B, Aldaz-Carroll L, Chabas S, Dausse E, Staedel C, Toulme JJ. Antisense oligonucleotides targeted to the domain IIId of the hepatitis C virus IRES compete with 40S ribosomal subunit binding and prevent in vitro translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:734–742. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komatsu Y, Yamashita S, Kazama N, Nobuoka K, Ohtsuka E. Construction of new ribozymes requiring short regulator oligonucleotides as a cofactor. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:1231–1243. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beaucage SL, Caruthers MH. Deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites - a new class of key intermediates for deoxypolynucleotide synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1859–1862. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfundheller HM, Lomholt C. Locked Nucleic Acids: Synthesis and Characterization of LNA-T diol. In: Beaucage SL, Bergstrom DE, Herdewijn P, Matsuda A, editors. Current protocols in nucleic acid chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2002. pp. 4.12.1–4.12.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen DS, Rosenbohm C, Koch T. Preparation of LNA phosphoramidites. Synthesis. 2002:802–808. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia TB, SantaLucia J, Burkard ME, Kierzek R, Schroeder SJ, Jiao XQ, Cox C, Turner DH. Thermodynamic parameters for an expanded nearest-neighbor model for formation of RNA duplexes with Watson-Crick base pairs. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14719–14735. doi: 10.1021/bi9809425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borer PN. Optical properties of nucleic acids, absorption and circular dichroism spectra. In: Fasman GD, editor. CRC Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: Nucleic Acids. 3rd edn. Cleveland, OH: CRC Press; 1975. pp. 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards EG. Use of tables in calculations of absorption, optical rotatory dispersion and circular dichroism of polyribonucleotides. In: Fasman GD, editor. CRC Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: Nucleic Acids. 3rd edn. Cleveland, OH: CRC Press; 1975. pp. 596–603. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDowell JA, Turner DH. Investigation of the structural basis for thermodynamic stabilities of tandem GU mismatches: Solution structure of (rGAGGUCUC)2 by two-dimensional NMR and simulated annealing. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14077–14089. doi: 10.1021/bi9615710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vorbrüggen H, Krolikiewicz K. New catalysts for the synthesis of nucleosides. Angew. Chem. Intt. Ed. Eng. 1975;14:421–422. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niedballa U, Vorbruggen H. General synthesis of N-glycosides. 6. Mechanism of stannic chloride catalyzed silyl Hilbert-Johnson reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:2084–2086. doi: 10.1021/jo00874a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niedball U, Vorbrugg H. Synthesis of nucleosides. 12. General synthesis of N-glycosides. 4. Synthesis of nucleosides of hydroxy and mercapto N-heterocycles. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:3668–3671. doi: 10.1021/jo00939a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niedball U, Vorbrugg H. Synthesis of nucleosides. 9. General synthesis of N-glycosides. 1. Synthesis of pyrimidine nucleosides. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:3654–3660. doi: 10.1021/jo00939a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greene TW, Wuts PGM. Protective groups in organic synthesis. New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: Wiley, J. & Sons, Inc.; 1999. Protection for the hydroxyl group, including 1,2- and 1,3-diols; pp. 17–245. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guibe F. Allylic protecting groups and their use in a complete environment. 1. Allylic protection of alcohols. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:13509–13556. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guibe F. Allylic protecting groups and their use in a complex environment -Part II: Allylic protecting groups and their removal through catalytic palladium piallyl methodology. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:2967–3042. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okamoto I, Shohda K, Seio K, Sekine M. A new route to 2'-O-alkyl-2-thiouridine derivatives via 4-O-protection of the uracil base and hybridization properties of oligonucleotides incorporating these modified nucleoside derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:9971–9982. doi: 10.1021/jo035246b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gigg J, Gigg R. The allyl ether as a protecting group in carbohydrate chemistry. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1966;82:82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasternak A, Kierzek E, Pasternak K, Fratczak A, Turner DH, Kierzek R. The thermodynamics of 3'-terminal pyrene and guanosine for the design of isoenergetic 2'-O-methyl-RNA-LNA chimeric oligonucleotide probes of RNA structure. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1249–1258. doi: 10.1021/bi701758z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kowalak JA, Dalluge JJ, McCloskey JA, Stetter KO. The role of posttranscriptional modification in stabilization of transfer-RNA from hyperthermophiles. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7869–7876. doi: 10.1021/bi00191a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sylvers LA, Rogers KC, Shimizu M, Ohtsuka E, Soll D. A 2-thiouridine derivative in transfer RNA(Glu) is a positive determinant for aminoacylation by Escherichia coli glutamyl-transfer RNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3836–3841. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shohda K, Okamoto I, Wada T, Seio K, Sekine M. Synthesis and properties of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine and oligoribonucleotides containing 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:1795–1798. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamoto I, Seio K, Sekine M. Study of the base discrimination ability of DNA and 2'-O-methylated RNA oligomers containing 2-thiouracil bases towards complementary RNA or DNA strands and their application to single base mismatch detection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:6034–6041. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okamoto I, Shohda K, Seio K, Sekine M. Incorporation of 2'-O-methyl-2-thiouridine into oligoribonucleotides induced stable A-form structure. Chem. Lett. 2006;35:136–137. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wengel J. Synthesis of 3'-C- and 4'-C-branched oligodeoxynucleotides and the development of locked nucleic acid (LNA) Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaur H, Arora A, Wengel J, Maiti S. Thermodynamic, counterion, and hydration effects for the incorporation of locked nucleic acid nucleotides into DNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7347–7355. doi: 10.1021/bi060307w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wengel J, Petersen M, Nielsen KE, Jensen GA, Hakansson AE, Kumar R, Sorensen MD, Rajwanshi VK, Bryld T, Jacobsen JP. LNA (locked nucleic acid) and the diastereoisomeric alpha-L-LNA: Conformational tuning and high-affinity recognition of DNA/RNA targets. Nucl. Nucl. Nucl. Acids. 2001;20:389–396. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fahmy RG, Khachigian LM. Locked nucleic acid modified DNA enzymes targeting early growth response-1 inhibit human vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2281–2285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petersen M, Wengel J. LNA: a versatile tool for therapeutics and genomics. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:74–81. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elmen J, Thonberg H, Ljungberg K, Frieden M, Westergaard M, Xu YH, Wahren B, Liang ZC, Urum H, Koch T, Wahlestedt C. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) mediated improvements in siRNA stability and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:439–447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fratczak A, Kierzek R, Kierzek E. LNA-modified primers drastically improve hybridization to target RNA and reverse transcription. Biochemistry. 2009;48:514–516. doi: 10.1021/bi8021069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fluiter K, Frieden M, Vreijling J, Rosenbohm C, De Wissel MB, Christensen SM, Koch T, Orum H, Baas F. On the in vitro and in vivo properties of four locked nucleic acid nucleotides incorporated into an anti-H-Ras antisense oligonucleotide. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1104–1109. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt KS, Borkowski S, Kurreck J, Stephens AW, Bald R, Hecht M, Friebe M, Dinkelborg L, Erdmann VA. Application of locked nucleic acids to improve aptamer in vivo stability and targeting function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5757–5765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vester B, Lundberg LB, Sorensen MD, Babu RB, Douthwaite S, Wengel J. LNAzymes: incorporation of LNA-type monomers into DNAzymes markedly increases RNA cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124 doi: 10.1021/ja0276220. 13682-12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kierzek E, Kierzek R. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4472–4480. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kierzek E, Pasternak A, Pasternak K, Gdaniec Z, Yildirim I, Turner DH, Kierzek R. Contributions of stacking, preorganization, and hydrogen bonding to the thermodynamic stability of duplexes between RNA and 2'-O-methyl RNA with Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) Biochemistry. 2009;48:4377–4387. doi: 10.1021/bi9002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]