Abstract

The family structure of older Japanese is projected to change dramatically as a result of very low fertility, increasing levels of non-marriage, childlessness, and divorce, and declining intergenerational coresidence. To provide an empirical basis for speculation about the implications of projected increases in single-person and couple-only households, we use two sources of data to describe relationships between family structure and the physical and emotional well-being of Japanese men and women age 60 and above. We find that marriage is positively associated with self-rated health and emotional well-being among older men but not women. In contrast to expectations, however, we find only limited evidence that the presence of children contributes to well-being. Taken as a whole, our results suggest that declines in marriage may have negative implications for the well-being of older Japanese men while the implications of declines in fertility and intergenerational coresidence may be less than popularly believed.

Keywords: Japan, aging, elderly, living arrangements, family, well-being, health

Rapid population aging is expected to have important implications for the well-being of older men and women. At the aggregate level, projected growth in the absolute and relative size of elderly populations will challenge the viability of existing social security and public health care programs (e.g., Aaron and Reischauer 2002; Bongaarts 2004). At the family level, the demographic processes underlying population aging are projected to bring about changes that may reduce access to family-provided support at older ages. Projected increases in single-person elderly households and childless elderly (Wachter 1997, Yi et al. 2006) are of particular concern given that spouses and children are the primary source of support for the elderly (Shanas 1979). This concern has motivated a good deal of research on linkages between family structure and well-being at older ages. In the U.S., this research has shown that physical and emotional well-being are lower among the unmarried whereas children do not appear to be strongly related to well-being (Hughes and Waite 2002; Koropeckyj-Cox, Pienta, Brown 2007).

For several reasons, the implications of family changes associated with population aging may be particularly pronounced in Japan. The first is the pace and magnitude of projected change in the size and family characteristics of Japan’s elderly population. As described in greater detail below, Japan’s population is aging at an unprecedentedly rapid pace and projected changes in family structure at older ages are more pronounced than in many other settings. As a result of substantial changes in patterns of marriage and childbearing, future cohorts of elderly Japanese men and women will have fewer children than today’s elderly and will be significantly more likely to have no children, to have never married, and to have divorced.

A second reason is the distinctive context in which families provide support to the elderly. Japan resembles most other industrialized societies in that spouses and children(-in-law) are the most important sources of physical care and emotional support for the elderly (Kendig, Hashimoto, and Coppard 1992) but differs in that much of this support takes place in the context of multi-generation households (Hashimoto 1996). Coresidence with children may be a particularly important predictor of well-being among the elderly in Japan, where normative expectations of coresidence and filial support are strong and the use of assisted living facilities is relatively limited.

Considering both the magnitude of projected demographic change and the normative and functional importance of intergenerational coresidence, it is important to note that the proportion of older Japanese coresiding with children has declined steadily over the past forty years. Changing attitudes toward coresidence and family-based care provision (Ogawa and Retherford 1993) suggest that this trend is likely to continue. Further reduction in intergenerational coresidence, combined with the projected changes in family structure brought about by significant long-term declines in marriage and fertility, may limit older persons’ access to family-provided support at the same time that rapid changes in population age structure limit the government’s capacity to maintain current, relatively generous, levels of public support.

To facilitate informed speculation about the potential impact of projected changes in the family circumstances of future cohorts of older Japanese, we use existing data to describe relationships between family structure and well-being among current cohorts of elderly. In doing so, we extend existing work in several ways. First, we focus explicitly on dimensions of family structure that are projected to change most rapidly as a result of trends in fertility, marriage, and living arrangements. Given projected declines in the capacity to maintain current levels of public support for the rapidly growing elderly population (Ogawa and Retherford 1997), we are particularly interested in evaluating the extent to which those family circumstances projected to increase most rapidly (e.g., single-person households) are associated with lower levels of well-being at older ages. Second, we focus on gender differences in the relationships between family structure and well-being. Existing evidence of gender differences in the relationship between household structure and well-being at older ages in the U.S. (e.g., Hughes and Waite 2002) highlights the importance of identifying how family circumstances may be differentially related to the well-being of older men and women in a more highly gender stratified context such as Japan. Third, we examine both cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between family structure and well-being. Cross-sectional analysis enables us to provide an up-to-date summary of relationships between family structure and well-being whereas longitudinal analysis enables us to evaluate theoretically interesting, but understudied, relationships between family circumstances and trajectories of well-being across older ages.

Background

Long-term trends in vital processes have important implications for family structure across the life course (Watkins, Menken, and Bongaarts 1987). Two of the most notable demographic changes during the past several decades – the transition to very low fertility and continued decline in mortality at older ages – are projected to result in rapid population aging at the aggregate level (United Nations 2003) and substantial change in family composition at the individual level. Mirroring aggregate changes in population age structure, family structure will shift from a pyramid shape to a “beanpole” shape comprised of multiple generations of similar and small size (Bengtson and Silverstein 1993). In the U.S., the large baby boom cohorts now approaching older ages will have fewer children on average than today’s elderly and a larger proportion will be childless (Hughes and O’Rand 2004). Projected increases in the proportion of older Americans who never marry are small (Goldstein and Kenney 2001) but the baby boom cohorts now approaching old age are much more likely than their predecessors to have divorced (Hughes and O’Rand 2004).

Given the fundamental importance of family-provided support to the elderly, these projected changes in family structure have generated growing interest in relationships between family circumstances and the well-being of older men and women. Just as earlier theorizing emphasized potential decline in family-provided support for the elderly in industrializing societies (Cowgill 1986), recent research focuses on the implications of projected changes in family structure for access to family support in rapidly aging societies. In the U.S., much of this work has focused on the implications of marriage, divorce, and childlessness for well-being at older ages. Results consistently demonstrate that married men and women fare better in terms of functional status (Waite and Hughes 1999), depression (Koropeckyj-Cox, Pienta, Brown 2007; Zhang and Hayward 2001), and mortality (Lillard and Waite 1995). These relationships are only partially explained by the selection of healthier individuals into marriage and are thought to reflect social and emotional support, behavioral monitoring, and more favorable economic circumstances among the married (Rogers, Hummer, and Nam 2000; Ross, Mirowsky, and Goldstein 1990). Social support and monitoring appear to be particularly beneficial for men whereas economic resources are more important for the well-being of women (Waite and Gallagher 2000).

Children appear to be less important than marriage for the well-being of older Americans. Intergenerational contact is positively associated with psychological well-being (Umberson 1992) but evidence regarding the relationship between coresidence with children and emotional well-being is mixed. Some studies find no relationship or a negative relationship whereas others find a positive relationship (Ross, Mirowsky, and Goldstein 1990). This empirical ambiguity may reflect the fact that intergenerational coresidence is not a normative arrangement in the U.S. The benefits of coresidence enjoyed by some elderly parents in need of support may be offset by the stresses of coresidence for others whose children have returned to the parental home following divorce or in response to other difficult life circumstances (Aquilino 1990).

Several recent studies find little support for the hypothesis that childlessness, by limiting the social support network of older men and women, is associated with lower levels of well-being at older ages. In general, the psychological well-being of childless elderly is similar to that of parents (Koropeckyj-Cox 1998). However, Zhang and Hayward (2001) find that childlessness is associated with higher levels of depression among the unmarried elderly, suggesting that the presence of children may compensate for the absence of a spouse. This appears to be particularly true for men. The implications of divorce may also be particularly relevant for older men whose relatively limited contact with children reduces access to family-provided support (Furstenberg, Hoffman, and Shrestha 1995).

The Japanese context

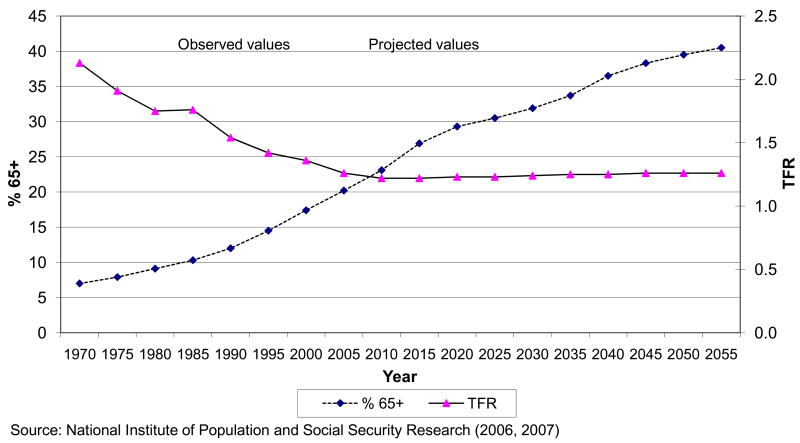

There are several reasons to expect that the implications of projected family change for well-being at older ages may be particularly pronounced in Japan. Japan’s population is aging at an unprecedentedly rapid pace and the extent of associated family changes is projected to be far more dramatic than in the U.S. As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of the Japanese population age 65 and over increased from 7% in 1970 to 20% in 2005 and is project to reach 40% by 2050 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, NIPSSR hereafter, 2006).1 To a large extent, this extremely rapid aging of the Japanese population reflects the long-term trend to very low fertility. In Figure 1, we also show that the Total Fertility Rate has declined steadily from 2.13 in 1970 to 1.26 in 2005, that it has been below replacement level for 40 of the past 50 years, and that Japan’s official population projections are based on an assumption that period fertility will remain well below replacement level.

Figure 1.

Trends in the Proportion aged 65+ and the Total Fertility Rate, 1970–2050

Because marital fertility has remained relatively stable over time, the decline in Japan’s fertility rate primarily reflects the trend toward later marriage and more recent increases in the proportion who will never marry.2 The proportion never married at age 50–54 was less than 5% for both men and women born in the 1930s (NIPSSR 2007) but is projected to increase to 15% for men and women in born in the early 1970s and further to 24% for those born after 1990 (NIPSSR 2006). Because childbearing and marriage remain closely linked in Japan, this increase in non-marriage implies similar increases in the projected proportion that is childless.3 Calculations based on official population projections suggest that the proportion of women who never have children will increase from 5% for those currently age 65 to about 25% for those who will reach age 65 in the 2030s (Iwasawa 2007). Substantial increase in the likelihood that marriages end in divorce is expected to contribute to further change in the family structure of older Japanese men and women.4

The impact of these family changes may be particularly strong in Japan given the prevalence and normative importance of intergenerational coresidence. Coresidence with children has long been viewed as the normatively ideal living arrangement at older ages (Kurosu 1994) and the extended family has played a central role in the provision of physical, emotional, and financial support to the elderly. The elderly have long commanded respect within the family (Palmore and Maeda 1985) and attitudinal surveys have consistently shown that large proportions of Japanese view intergenerational coresidence and caring for elderly parents as a “good custom” or “natural duty” (Ogawa and Retherford 1993). Intergenerational coresidence remains a relatively common arrangement, family-provision of care to frail elderly is substantial, and children continued to be widely viewed as an important source of support in old age.

Expectations of family-provided support to the elderly also figure prominently in public policy discussions. Over the past 30–40 years, public support for the elderly in Japan has become increasingly generous and the ratio of public pension benefits to pre-retirement income is now similar to that in the U.S. (Fukawa 2004; Gruber and Wise 1999), health expenditures on the elderly are relatively high in comparative perspective (Anderson and Hussey 2000), and Japan is one of the only countries with mandatory long-term care insurance (Campbell and Ikegami 2000). While recent policy efforts to address the implications of population aging have reduced public pension benefit levels, raised the age of pension eligibility (Takayama 2001), and reduced public spending on health care (Ikegami and Campbell 2004), there is also continued interest in facilitating and promoting family-based provision of care to frail elders (Ogawa and Retherford 1997). It seems clear, however, that families’ capacity to provide support to the elderly will be challenged not only by the projected demographic changes described above, but also by changes in living arrangements and attitudes toward intergenerational support.

The long-term decline in coresidence with adult children is well documented. The proportion of older Japanese coresiding with a child(ren) was over .75 in the 1970s (Ogawa and Retherford 1997) but declined to .45 in 2005 (NIPSSR 2007). Survey data indicating substantial decline in both favorable attitudes toward coresidence and expectations of coresidence (Ogawa and Retherford 1993) suggest the potential for further declines in the proportion of older Japanese living in extended families. At the same time, it is important to note that a substantial proportion of older Japanese live relatively close to their children. Half of Japanese aged 65+ have a child living within one hour, including 15% with a child living within five minutes distance (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2006). While residential proximity is likely to facilitate the provision of support to older family members, access to this type of support is also expected to decline as a result of declining fertility and increasing childlessness. As these demographic, behavioral, and attitudinal changes combine to alter the structure of Japanese families and the nature of intergenerational relationships, it is important to understand the extent to which family forms projected to increase most rapidly are associated with the well-being of older men and women.

Existing research on family structure and well-being at older ages in Japan is relatively limited. Recent studies of older Japanese have shown that, as in the U.S., marriage is positively associated with happiness (Naoi 2001) and negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Inaba et al. 2005; Kikuzawa 2001, 2006). However, the benefits of marriage are less pronounced in Japan, perhaps reflecting the tendency of current cohorts of older Japanese couples to prioritize parent-child relationships over spousal relationships (Ochiai 1997). Strong normative expectations of coresidence and the importance of intergenerational relationships suggest that coresidence should be positively associated with well-being but evidence from previous research is mixed. Some studies have found no association between coresidence and subjective well-being (Naoi 1990) or mortality (Sugisawa 1994) while others have found significant positive associations for those who do not have a spouse (Naoi 2001). Findings on the effect of childlessness are also mixed, with some studies concluding that childlessness is associated with higher depressive symptoms (Kikuzawa 2006) while others find no association (Kikuzawa 2001).

The current study

Our goal in this paper is to update earlier research by providing a descriptive overview of relationships between family structure and the physical and emotional well-being of current cohorts of older men and women in Japan. By focusing on relationships between family structure and well-being among today’s elderly, we are able to establish an empirical basis for speculating about prospects for future cohorts as well as a valuable benchmark against which to evaluate the subsequent experiences of those cohorts. We focus on aspects of family structure projected to change most dramatically in the years to come – marital status, coresidence with children, and the presence of children. Because divorce, non-marriage, and childlessness are still uncommon among current cohorts of elderly Japanese, we focus more generally on differences between those who do and do not have a spouse and differences between those who do and do not live with a child.

We expect that the gender differences identified in research on the family circumstances and well-being of older Americans (Hughes and Waite 2002) may be even more pronounced in Japan. In particular, substantial gender asymmetry in work and family roles across the life course suggests that marriage may be more beneficial for men than for women. Evidence that men’s social support networks beyond the workplace are very limited (Yamato 1996) also suggests that marriage may be particularly beneficial for older men who have left the labor force. Because many older Japanese women have worked intermittently across the life course and are economically dependent on their husbands, marriage is clearly beneficial for women’s economic well-being (Shirahase 2006). Net of economic resources, however, gender asymmetry in the division of labor and the low prevalence of “companionate” marriages suggests that marriage may be unrelated, or perhaps negatively related, to older women’s well-being. Evidence that emotional ties to children are much stronger among mothers than fathers (Kendig et al. 1999) suggests that the presence of children may be more beneficial for older women.

An important feature of our analyses is the fact that we examine relationships between family structure and well-being both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. To date, most studies in the U.S., and almost all related studies in Japan, have focused on cross-sectional relationships. Cross-sectional analyses are essential for providing timely information in the context of rapid social and demographic change but are limited in two important ways. The first is that they do not allow for inference about the causal direction of relationships between family structure and well-being. With cross-sectional data, it is not possible to determine whether family structure impacts well-being in the ways posited above or whether well-being influences family structure. For example, earlier findings of no relationship between coresidence and well-being may reflect the offsetting influences of the posited benefits of coresidence and poor health as a reason for initiating intergenerational coresidence at older ages (Brown et al. 2002).

The second limitation of cross-sectional analysis is that it precludes inferences about the extent to which family structure is associated with trajectories of well-being at older ages. Life course research stresses the importance of growing heterogeneity in the life circumstances of people approaching old age (O’Rand 1996a) and several recent studies have focused on the progression of disparities in health and well-being at older ages (Herd 2006; Liang et al. 2005; Lynch 2003). Does the pattern of increasing variation in well-being continue across older ages, as suggested by notions of cumulative advantage and disadvantage (O’Rand 1996b)? Does it decelerate, as suggested by the notion of “age as leveler” (Ferraro and Farmer 1996)? Does it accelerate? How are trajectories of well-being related to family circumstances? How do changes in family circumstances impact trajectories of well-being? Is the impact of nonnormative family changes (e.g., widowhood for men) greater than that of more normative changes (e.g., widowhood for women)? Do older people recover from the impact of changes in family circumstances such as loss of spouse? If so, how quickly? These are important questions about linkages between family and well-being at older ages that can only be addressed via the analysis of longitudinal information on family circumstances and well-being across a range of older ages.

Data and methods

Data

Our analyses are based on two sources of data. We first describe recent cross-sectional relationships between family structure and well-being using data from the 1998 and 2003 rounds of the National Family Research of Japan (NFRJ) survey. The NFRJ is a nationally representative survey of men and women age 28 and above conducted by the Japan Society of Family Sociology. Response rates were 67% in 1998 and 63% in 2003 (Inaba 2004; Tanaka 2005). Limiting our focus to respondents age 60 and over provides us with a sample of 4,216.

We then examine relationships between family structure and trajectories of well-being across older ages using six waves of data from the National Survey of Japanese Elderly (NSJE). The NSJE is a longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized men and women age 60 and over. The first survey was conducted in 1987 and follow-up interviews have been conducted at three-year intervals. Supplemental samples of younger respondents were added at waves 2 (1990) and 4 (1996) and a supplemental sample of men and women age 70+ was added at wave 5 (1999). Response rates for were 67% at wave1, 78% at wave2, 76% at wave 3, 76% at wave 4, 74% at wave 5, and 73% at wave 6. Pooling data across waves provides us with a sample of 13,929 observations.

The NFRJ and NJSE contain comparable measures of family structure and multiple indicators of well-being. In the analyses presented here, we evaluate the extent to which self-rated health and emotional well-being are associated with presence of a spouse, coresidence with children, and geographic proximity to non-coresident children.

Measures

Self-rated health: Both surveys include a standard, five-category measure of self-rated health, ranging from 1= poor health to 5= excellent health.

Emotional well-being: Both surveys contain versions of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) but the construction of the indices differs somewhat across surveys. In the NFRJ, the measure is based on ten different questions with four response options (1 = never, 2 = 1–2 days per week, 3 = 3–4 days per week, and 4 = almost every day) and thus ranges from 10–40. In the NSJE, the measure is based on seven different items with three response options (1 = hardly ever, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = often) and thus ranges from 7–21.5,6 To facilitate interpretation, we reverse code these CES-D measures so that higher values represent better mental health and hereafter refer to this measure as “emotional well-being.”

Family characteristics: For both surveys, we construct a four-category measure of household structure that cross-classifies respondents by marital status and coresidence (married and not coresiding with children[-in-law], married and coresiding, not married and not coresiding, not married and coresiding). Given the high prevalence of intergenerational residential proximity in Japan, we also construct a dichotomous measure of geographic proximity to children indicating whether or not at least one non-coresident child lives within one hour of the respondent.

Other variables: In all models, we include other variables that we expect are related to both well-being and family circumstances. These are age, education (in years), current work status (working, not working), homeownership (yes, no), and joint spousal income (a categorical measure of reported income with a separate category for those who refused to answer or said “don’t know”).7

In the NFRJ analyses, we excluded cases with missing values on the dependent variables and imputed values for educational attainment, the only other variable with a non-trivial amount of missing data. In the NSJE analyses, we imputed values for all variables with missing data, including the dependent variables, in order to minimize loss of information on individual trajectories. In neither case did we need to impute values for more than a very small proportion of respondents. Educational attainment was imputed for 2% of the NFRJ sample and CES-D, the variable with the most missing values in the NSJE sample, was imputed for less than 1% of respondents. We imputed values for missing data using the ICE routine for multiple imputation in Stata (Royston 2005) and conducted analyses using five imputed data sets for each of the two surveys.

Methods

To describe cross-sectional relationships between family structure and well-being, we use the NFRJ data to estimate ordered logistic regression models for self-rated health and linear regression models for CES-D. We estimate all models separately for men and women.

To describe relationships between family structure and trajectories of well-being we use the longitudinal information in the NSJE to estimate growth-curve models. Using the notation of Raudenbush and Bryk (2002), these models can be expressed as:

Level 1 Model (repeated-observations model):

Level 2 Model (person-level model):

where bold font indicates a vector of variables or coefficients. The dependent variable in the level-1 model (Wit) is the measure of well-being for individual i at time t (years since first observation). T ranges from 0–15, with the minimum value observed when respondents were first observed and the maximum value observed for those respondents who were first observed in wave 1 (1987) and remained in the sample until wave 6 (2002). The coefficient for this variable (π1) describes linear change in well-being across repeated observations. X contains two time-varying correlates of physical and emotional well-being – current employment status and joint spousal income.

The family characteristics of older Japanese men and women are quite stable (Brown et al. 2002) but there are important transitions, such as widowhood, that may affect trajectories of well-being. To assess the impact of changes in family circumstances, we include two indicators of family change in the level-1 equation. The first is (Yit−Yi0), the difference between the current value of a given family status variable (at time t) and the value at first observation (at time t=0). We construct three measures of change – one for coresidence with children, one for presence of a proximate (non-coresident) child, and one for presence of a spouse. The first measure takes three values – 0 if no difference, 1 if currently coresiding but not coresiding at first observation and −1 if currently not coresiding but coresiding at baseline. The second measure takes on analogous values for presence of a proximate child and the third takes values of 0 if no change and 1 if married at first observation but not married at time t (i.e., widowhood). We do not include an indicator of the transition from unmarried to married given the rarity of this event in these data.

The level-1 intercept in this model (π0) thus represents the level of well-being for respondent i (a respondent with reference values for both work status and spousal income and no change in family circumstances across multiple observations) at his/her first observation. As shown in the level-2 model for π0, this level-1 intercept is specified as a function of individual characteristics at first observation (Zi0), including the initial values of the other dimension of well-being, the family characteristics described above (Yi0), age at first observation (Ai0), and an individual-specific, time-invariant random effect (r0i). The coefficient associated with Ai0 (β03), together with the coefficient for time since initial observation (π1), allows us to describe trajectories of well-being by age.

The slope of the trajectory of well-being across time (π1) is specified as a function of family characteristics at first observation (Y) and other baseline characteristics (Z). Estimated values of β01 describe differences in levels of well-being with respect to family characteristics at first observation (i.e., the trajectory intercept). Estimated values of β11 describe family differences in the rate of change in well-being subsequent to first observation (i.e., the trajectory slope). Because the number of observations is small for many respondents, we specify a linear slope for the trajectories of well-being in the models presented below (see Liang et al. 2005 for similar analyses of self-rated health trajectories based on the NSJE data). Unlike the random intercept (π0), π1 is constant across all observations. The same is true of π2, π3, and π4.

The coefficients for measures of family change subsequent to first observation (π3) describe the extent to which family change is associated with a shift in the level of a given trajectory of well-being. The way in which we have constructed the indicators of family change implies that the magnitude of change in one direction is equal to the magnitude of change in the other direction.8 The final component of the trajectory models is the interactions between time and the indicators of family change, Tit(Yit−Yi1). The coefficients for these variables (π4) describe the extent to which family changes are associated with change in the slope of a given trajectory of well-being (see Horney, Osgood, and Marshall 1995 for the use of similar models in a different context). Inclusion of these interaction terms allows us to assess the extent to which shifts in the level of a given trajectory (represented by π3) are permanent or transitory. Finding that π4 is equal to zero would imply that the impact of family change on well-being is permanent. However, an estimated coefficient that is significantly different from zero and of the opposite sign of π3 would imply that there is some recovery (or regression, more generally) following changes in well-being brought about by a change in family structure. As in the cross-sectional analysis, the level-1 model for self-rated health is estimated using ordered logistic regression and the level-1 model for CES-D is estimated via OLS.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Before discussing the results of the cross-sectional and trajectory analyses, we briefly present descriptive statistics for each dimension of well-being and summarize the distributions of other variables in the models. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the two rounds of NFRJ data on the left and the six waves of NSJE data on the right. For the NSJE, we summarize both level-1 (time-varying) variables and level-2 variables (values at first observation). In both surveys, gender differences in the two measures of well-being are small, with women having slightly lower-levels of well-being (i.e., lower values of both self-rated health and emotional well-being). A comparison of values at first observation with mean values across all observations in the NSJE suggests that both physical and emotional well-being decline somewhat with age. With a few exceptions, the characteristics of the NFRJ and NSJE samples are similar. The NFRJ respondents are, on average, about four years younger and are somewhat more likely to be employed, more likely to be living with spouse only, and have somewhat higher education than their counterparts in the NSJE.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Data

| NFRJ | NSJE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||||

| Variable | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. |

| Measures of Well-being | ||||||||

| Self-rated health | 3.39 | 0.99 | 3.48 | 0.99 | 3.41 | 1.00 | 3.58 | 1.04 |

| Self-rated health at first observation | 3.50 | 0.99 | 3.74 | 1.03 | ||||

| CES-D | 36.37 | 4.72 | 36.64 | 4.35 | 19.58 | 2.15 | 20.04 | 1.82 |

| CES-D at first observation | 19.81 | 1.97 | 20.21 | 1.65 | ||||

| Family structure | ||||||||

| Married and not coresiding | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.40 | ||||

| Not married and not coresiding | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.04 | ||||

| Not married and coresiding | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.05 | ||||

| Married and coresiding | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.51 | ||||

| Proximate child(ren) | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.61 | ||||

| Change in Family structure | ||||||||

| Lost spouse | 0.09 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Began coresiding | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Stopped coresiding | 0.06 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Proximate moved distant | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Distant child moved proximate | 0.06 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Other variables | ||||||||

| Age | 67.51 | 5.05 | 67.31 | 4.72 | 72.38 | 7.12 | 71.34 | 6.83 |

| Age at first observation | 67.44 | 6.33 | 66.73 | 6.09 | ||||

| Working | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.42 | ||||

| Income (NFRJ) | ||||||||

| Lowest tertile | 0.39 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Middle tertile | 0.30 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Highest tertile | 0.23 | 0.37 | ||||||

| DK/NR | 0.08 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Income (NSJE) | ||||||||

| <1.2 million yen | 0.29 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 1.2–3 million yen | 0.33 | 0.36 | ||||||

| 3–5 million yen | 0.13 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 5 million yen or more | 0.07 | 0.14 | ||||||

| DK/NR | 0.18 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Educational attainmenta | 10.81 | 1.88 | 11.55 | 2.52 | 8.72 | 2.46 | 9.85 | 2.96 |

| Home ownershipa | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.87 | ||||

| N | 2,168 | 2,048 | 7,952 | 5,977 | ||||

refers to first observation for NSJE

Cross-sectional associations

Table 2 presents the results of multivariate models based on the cross-sectional NFRJ data for self-rated health (left) and emotional well-being (right). Coefficients for the ordered logistic regression models of self-rated health represent the log-odds of being in a higher category (i.e., better health). Positive (negative) coefficients thus indicate associations with better (worse) health. Similarly, in the OLS models for the reverse coded measure of CES-D, positive coefficients correspond to higher levels of emotional well-being.

Table 2.

Estimated Coefficients for Cross-sectional Models for Self-rated Health and Emotional Well-beinga

| Self-rated health | Emotional Well-beingb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Family structure | ||||

| Married and not coresiding (ref) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Married and coresiding | −0.10 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.46* |

| Not married and not coresiding | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.40 | −1.51** |

| Not married and coresiding | 0.08 | −0.51* | −0.33 | −1.63** |

| Proximate child(ren) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.22 | −0.04 |

| Age | −0.03** | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Working | 0.38** | 0.62** | 0.63* | 0.12 |

| Income | ||||

| Lowest tertile | −0.20# | −0.38** | −0.43 | −1.03** |

| Middle tertile (ref) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Highest tertile | 0.21# | 0.24* | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| DK/NR | 0.24 | −0.56** | 0.51 | −0.75# |

| Educational attainment | 0.07** | 0.07** | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Home ownership | 0.17 | 0.25# | 1.29** | 0.71* |

| N | 2,102 | 1,989 | 1,977 | 1,912 |

| Log-likelihood | −2,660 | −2,463 | ||

| R2 | 0.024 | 0.031 | ||

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Notes:

These models are estimated using data from the NFRJ

The dependent variable in this model is the CES-D score reverse coded so that higher values correspond to better emotional health

Self-rated health: Family characteristics are not significantly related to women’s self-rated health. Among men, self-rated health is relatively low among those who are unmarried and living with children. This appears to primarily reflect a positive relationship between marriage and self-rated health. Conditional on marital status, differences with respect to coresidence with children are not statistically different from zero.9

Emotional well-being (reverse coded CES-D): As in the model for self-rated health, family characteristics are unrelated to women’s emotional well-being. Coefficients are large and negative for those without a spouse but these differences are not statistically different from zero. For men, however, emotional well-being is significantly lower among those without a spouse (i.e., living with children only or living alone). Among men who are married, emotional well-being is significantly higher for those living with their spouse only relative to those living with both their spouse and children. These results suggest that the emotional well-being of older Japanese men is positively related to marriage and negatively related to coresidence with children.

Trajectories of well-being

Table 3 presents the results of growth curve models based on the longitudinal NJSE data for self-rated health (left) and emotional well-being (right). For each model, we present two sets of coefficients describing relationships between family characteristics and both the level of well-being (β01 and β30 in the model above) and the rate of change in well-being (β11 and β40 in the model above). The first row of level-2 coefficients (middle of the table) presents the intercept and slope for respondents with mean values of continuous covariates (e.g., baseline emotional well-being) and reference values for categorical covariates (e.g., baseline family structure). These slope coefficients indicate that, for both women and men, self-rated health declines with age while emotional well-being appears to be stable.

Table 3.

Estimated Coefficients from Growth Curve Models for Self-rated Health and Emotional Well-being

| Self-rated health | Emotional Well-beinga | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 model | Women | Men | Women | Men |

| Working | 0.45** | 0.52** | 0.24** | 0.17** |

| Income | ||||

| <1.2 million yen (ref) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1.2–3 million yen | 0.06 | 0.18# | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| 3–5 million yen | 0.21* | 0.29* | 0.20* | 0.06 |

| 5 million yen or more | 0.36** | 0.39** | 0.24* | 0.12 |

| DK/NR | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.08 |

| Changes in family structure | ||||

| Lose spouse | −0.17 | −0.98** | −0.99** | −1.35** |

| Start coresiding | 0.36* | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.12 |

| Child moves within one hour | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| Changes in family structure × duration | ||||

| Lose spouse × duration | 0.03 | 0.07* | 0.07** | 0.07* |

| Start coresiding × duration | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Child moves w/in one hour × duration | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Level 2 modelb | π0 equation | π1 equation | π0equation | π1 equation | π0equation | π1equation | π0equation | π1equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (β00)/Slope (β01)c | −2.11** | −0.06** | −0.99# | −0.05** | 19.05** | −0.04 | 20.00** | −0.01 |

| Family structurea | ||||||||

| Married and not coresiding (ref) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Married and coresiding | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04* | 0.17* | 0.00 |

| Not married and not coresiding | 0.29* | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 | -0.33** | 0.06** | −0.55* | 0.00 |

| Not married and coresiding | 0.36** | −0.01 | −0.39# | 0.08** | −0.19# | 0.04* | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Proximate child(ren) | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.16* | 0.00 | 0.13# | 0.00 |

| Age at first observation | 0.00 | −0.02** | −0.01 | −0.01# | ||||

| CES-D | −0.24** | 0.01** | −0.31** | 0.01** | ||||

| Self-rated health | 0.52** | −0.01# | 0.39** | −0.01# | ||||

| Educational attainment | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Home ownership | 0.42** | −0.02 | 0.55* | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| N | 7,952 | 5,977 | 7,952 | 5,977 | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −18,975 | −14,257 | −17,055 | −11,833 | ||||

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Notes:

The dependent variable in this model is the CES-D score reverse coded so that higher values correspond to better emotional health

variables in level 2 model are measured at first observation

As noted in the text, β00 and β01 represent the intercept and slope, respectively, for respondents with mean values of continuous covariates and

-

Self-rated health: In contrast to the cross-sectional model, this model shows that being unmarried is associated with significantly better self-rated health for women. Relative to those in couple-only households, women who are not married have significantly better self-rated health (regardless of coresidence status). There is no evidence, however, that family circumstances are associated with the rate of change in older women’s self-rated health. For men, family characteristics are largely unrelated to self-rated health. As in the cross-sectional models, the coefficient for unmarried and living with children (−0.39) is large, negative, and statistically significant (at p < .10). At the same time, the rate of decline in self-rated health is significantly lower for men who were unmarried and coresiding with children at first observation.

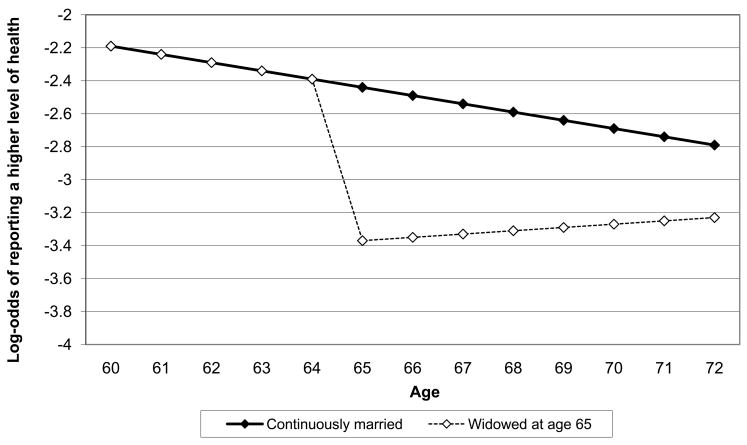

For men, but not for women, loss of spouse is associated with a large decline in self-rated health (π3 = −0.98). This appears to be a temporary decline in health that is offset by a shift in the slope. As shown in Figure 2, the self-rated health of a hypothetical man first observed at age 60 and widowed at age 65 appears to converge to the level of an otherwise similar continuously married man at older ages.10 Among women, but not men, initiation of coresidence is associated with an increase in self-rated health (π3 = 0.36) that appears to be permanent (i.e., the initiation of coresidence is not associated with a significant change in the slope of women’s self-rated health trajectories). Previous studies have shown that poor health is associated with the likelihood of initiating coresidence at older ages (Brown et al. 2002) and our results suggests that there is some improvement in self-rated health subsequent to this change in living arrangements. The positive coefficient for initiation of coresidence also implies, by construction, that children leaving home is associated with a decline in women’s self-rated health.

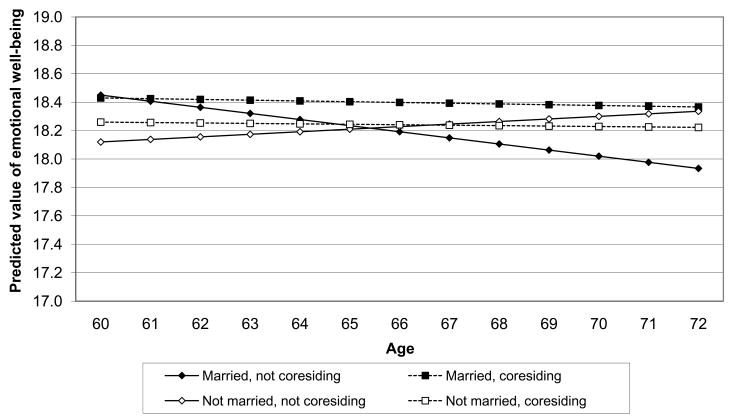

Emotional well-being (reverse coded CES-D): In contrast to the results for self-rated health, levels of emotional well-being are lower for women who are not married. This same pattern was observed in the cross-sectional models but was not statistically significant. This model also provides some evidence that the rate of change in women’s emotional well-being depends on family structure at baseline. Specifically, we see that emotional well-being declines with age only for women in couple-only households (the reference family status category). Emotional well-being is stable for women who are coresiding with children (regardless of marital status) and appears to improve with age for women who were living alone at first observation (i.e., β01 = −0.04 plus β11 = 0.06 is greater than zero). As shown in Figure 3, these differences in the slopes of emotional well-being trajectories contribute to somewhat lower levels of well-being at later ages among women in couple-only households. This is an important insight into the relationship between family structure and well-being that is not visible using cross-sectional data.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of men’s self-rated health, the impact of widowhood

Figure 3.

Trajectories of women’s emotional well-being, by family structure at first observation

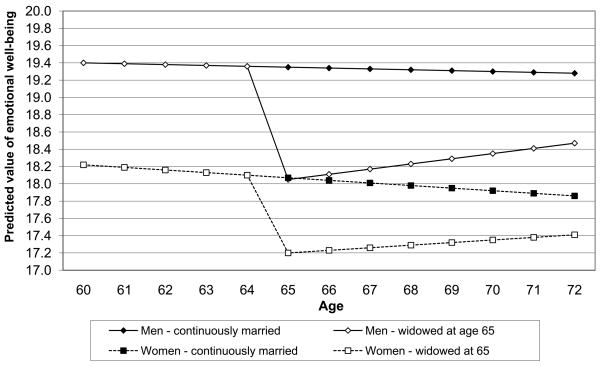

For men, like women, the lowest levels of emotional well-being are found among those living alone (as in the cross-sectional models). In contrast to the cross-sectional results, however, we also see that levels of emotional well-being among both married and unmarried men are higher if they are coresiding with children. The presence of proximate children is also associated with significantly higher levels of baseline emotional well-being for both men and women (β11 = 0.13 and 0.16, respectively). Loss of spouse is associated with a large decline in emotional well-being for women as well as men. However, this shift in the level of emotional well-being is largely offset by corresponding changes in the slopes of the trajectories (as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Trajectories of emotional well-being, the impact of widowhood

Discussion

Our goal in this paper was to provide an empirical basis for speculation about the potential implications of projected changes in family structure for the well-being of older men and women in Japan. The results of both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses suggest that relationships between family circumstances and well-being at older ages are different for men and women. This is especially true for marriage which, as in the U.S. (Waite and Gallagher 2000), appears to be particularly beneficial for men. Marriage is associated with better self-rated health and emotional well-being while widowhood is related to large, albeit temporary, declines in both the self-rated health and emotional well-being of men. This pattern may reflect men’s relative dependence on wives for instrumental and emotional support and/or the relatively nonnormative and thus unanticipated nature of widowhood for older men. In contrast, we find that married women report worse self-rated health and that married women in couple-only households are the only group to experience decreases in emotional well-being across older ages.

In contrast to widespread belief about the importance of children for old-age support (but consistent with previous studies), we find rather limited evidence that coresidence or proximate residence contributes to the well-being of either women or men. Among men, we find that coresidence with children and the presence of geographically proximate children are both positively associated with emotional well-being in the longitudinal, but not in the cross-sectional, analyses. Among women, we find that the initiation of coresidence is associated with an improvement in self-rated health and that the presence of a proximate child(ren) is associated with higher emotional well-being. As with men, these patterns are observed only in the longitudinal analyses. Based on these results, one might speculate that the large projected increases in childlessness and decreases in intergenerational coresidence will not have a substantial negative impact on the well-being of future cohorts of elderly. This may be particularly true if declining intergenerational coresidence is offset to some extent by increases in intergenerational geographic proximity.

There are many important ways in which subsequent research should extend what we have done in this paper. The first is to update our findings when cohorts more directly impacted by recent changes in marriage, divorce, and fertility reach old age. Our speculation is based on the assumption that the relationships between family structure and well-being we are able to observe today will remain relatively stable into the future. It is reasonable to expect, however, that these relationships may be very different for future cohorts of elderly. This is particularly true of non-marriage, divorce, childlessness, and other family characteristics that are currently very uncommon among older Japanese. Because the implications of being unmarried for well-being at older ages presumably differ depending on whether the absence of a spouse is the result of never marrying, divorcing, or widowhood, the fact that the vast majority of unmarried men and women in our sample were widowed makes it difficult to speculate about the implications of recent changes in marriage behavior among younger cohorts. The differences that we do observe highlight the importance of continued research on relationships between marital status and well-being at older ages, particularly among those who have divorced or never married. Recent evidence of increasing associations between men’s lower socioeconomic status and both non-marriage (Shirahase 2005) and divorce (Ono 2007) suggests that both selection and the health benefits of marriage may contribute to growing disparities in the well-being of older Japanese men. Among older women, the increasing likelihood of non-marriage and divorce may contribute to lower levels of well-being by reducing economic resources but our results do not suggest that the absence of a spouse per se is negatively associated with women’s physical or emotional well-being.

A second and related limitation is the fact that we have ignored remarriage and stepfamilies in this analysis because they are still uncommon among older Japanese and cannot be easily identified in either survey. Increasingly high levels of divorce suggest that remarriage and stepfamily dynamics will be a critically important dimension of family variation for subsequent cohorts of Japanese elderly. Given large projected increases in non-marriage and childlessness, subsequent research should also focus on the ways in which non-family social networks (e.g., friends, community) are associated with well-being at older ages.

One of the most intriguing conclusions from our analyses is that relationships between family circumstances and well-being among older Japanese men and women closely resemble those of their counterparts in the U.S. despite significant differences in the nature of living arrangements and family relationships in the two countries. In both settings, marriage is important for well-being, particularly among men, while coresidence or geographic proximity to children appears to be less important. These similarities may indicate that widowhood is a universally stressful event whereas physical and emotional well-being at older ages is relatively insensitive to the presence of children in societies where public support for the elderly is relatively generous. The former speculation highlights the importance of carefully distinguishing the extent to which the relative well-being of widows may differ from that of the increasing numbers of older men and women who have divorced or never married. The latter speculation highlights the importance of conducting similar analyses in other rapidly aging, low-fertility societies where public support for the elderly is less generous and family provided support more critical than is the case in Japan or the U.S.

Acknowledgments

The data for this analysis, National Family Research of Japan (conducted by the Japan Society of Family Sociology), were provided by the Social Science Japan Data Archive, Information Center for Social Science Research on Japan, Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo. This research was partially supported by grant R01-AG154124 (Jersey Liang PI) from the National Institute on Aging and by core grants to the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (R24 HD047873) and to the Center for Demography of Health and Aging at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (P30 AG017266).

Footnotes

Figure 1 presents the projected proportion age 65+ based on the medium-variant assumptions regarding mortality and fertility. The corresponding proportions for 2050 based on low- and high- variant assumptions of fertility and mortality are 43% and 36%, respectively.

Women’s mean age at first marriage rose from 24.2 in 1970 to 28.0 in 2005.

Only 2% of births in 2005 were registered to unmarried women.

Estimates based on recent data project that one-in-three Japanese marriages will end in divorce (Raymo, Iwasawa, and Bumpass 2004).

In waves 5 and 6 of the NSJE, these questions had four response categories. We collapse responses for “a little (1–2 days per week)” and “sometimes (3–4 days per week)” to create a category that corresponds to “sometimes” in waves 1–4.

Component questions in the NSJE were “I felt depressed,” “I felt lonely,” and “I felt sad,” “I had poor appetite,” “I felt that everything I did was an effort,” “My sleep was restless,” and “I couldn’t ‘get going’.” The NFRJ measures did not include the question about sleep but includes four other questions: “I felt fearful,” “I talked less than usual,” “I couldn’t concentrate,” and “I couldn’t shake off the blues even with help from family and friends.”

NSJE respondents were asked about combined spousal income whereas NFRJ respondents were asked about their own income and spouse’s income in separate questions. Combined spousal income in the NFRJ is thus constructed by summing the two responses. Categories differ somewhat across the two surveys, with the categories referring to specific income values in the NSJE data and to income tertiles in the NFRJ data. Category definitions are as indicated in Tables 1–3.

This simplifying assumption could be relaxed by using two dummy variables for change in either direction.

The z statistic for the difference between not married and coresiding (−.51) and not married and not coresiding (−.15) is 1.22.

These hypothetical trajectories are constructed by assuming that initial age at observation is 60 and setting employment status and annual joint income to their reference values (i.e., not employed and less than 1.2 million yen, respectively).

References

- Aaron HJ, Reischauer RD. Paying for an Aging Population. In: Infeld DL, editor. Disciplinary Approaches to Aging: vol. 5 Economics of Aging. New York: Routledge; 2002. pp. 5–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GF, Hussey PS. Population aging: a comparison among industrialized countries. Health Affairs. 2000;19:191–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS. The likelihood of parent-adult child coresidence: Effects of family structure and parental characteristics. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Silverstein M. Families, aging, and social change: Seven agendas for 21st-century researchers. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1993;13:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J. Population aging and the rising cost of public pensions. Population and Development Review. 2004;30:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Liang J, Krause N, Akiyama H, Sugisawa H, Fukaya T. Transitions in living arrangements among the elderly in Japan: Does health make a difference? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002;57B:S209–S220. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.s209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Ikegami N. Long-term care insurance comes to Japan. Health Affairs. 2000;19:26–39. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowgill D. Aging Around the World. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Farmer MM. Double jeopardy, aging as leveler, or persistent health inequality? A longitudinal analysis of white and black Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1996;51B:319–328. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.6.s319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukawa T. Japanese public pension reform from international perspectives. Japanese Journal of Social Security Policy. 2004;3:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Hoffman SD, Shrestha L. The effect of divorce on intergenerational transfers - new evidence. Demography. 1995;32:319–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Takahashi S, Hu Y. Mortality among Japanese singles: A reinvestigation. Population Studies. 1995;49:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JA, Kenney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage foregone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, AWise D. Introduction and Summary. In: Gruber J, Wise DA, editors. Social Security and Retirement around the World. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press; 1999. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto A. The Gift of Generations: Japanese and American Perspectives on Aging and the Social Contract. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Herd P. Do functional health inequalities decrease in old age?: Educational status and functional decline among the 1931–1941 birth cohort. Research on Aging. 2006;28:375. [Google Scholar]

- Horney J, Osgood DW, Marshall IH. Criminal careers in the short-term: Intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:655–673. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, O’Rand AM. The Lives and Times of the Baby Boomers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Health in household context: Living arrangements and health in late middle age. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:1–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami N, Campbell JC. Japan’s health care system: Containing costs and attempting reform. Health Affairs. 2004;23:26–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba A. Sampling design and data characteristics of NFRJ98. In: Watanabe H, Inaba A, Shimazaki N, editors. Family Structure and Family Change in Contemporary Japan: Quantitative Analyses of National Family Research (NFRJ98) Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 2004. pp. 15–24. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, Gove WR, Evenson RJ, Sloan M. Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:2280–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasawa M. Family formation in an era of population decline. In: Atoh M, Tsuya NO, editors. Japanese Society in an Era of Population Decline. Tokyo: Harashobo; 2007. pp. 53–81. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kendig H, Hashimoto A, Coppard L. Family Support for the Elderly: The International Experience. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kendig H, Koyano W, Asakawa T, Ando T. Social support of older people in Australia and Japan. Ageing and Society. 1999;19:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuzawa S. Aging, multiple roles, distress: Life stage as social context. Japanese Sociological Review. 2001;52:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuzawa S. Multiple Roles and Mental Health in Cross-Cultural Perspective: The Elderly in the United States and Japan. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:62–76. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj-Cox T. Loneliness and depression in middle and old age: Are the childless more vulnerable? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B:303–312. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.6.s303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj-Cox T, Pienta A, Brown T. Women of the 1950s and the “normative” life Ccourse: The implications of childlessness, fertility timing, and marital status for psychological well-being in late midlife. Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2007;64:299–330. doi: 10.2190/8PTL-P745-58U1-3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu S. Who lives in the extended family and why? The case of Japan. In: Cho L-J, Yada M, editors. Tradition and Change in the Asian Family. Honolulu, HI: East-West Center; 1994. pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Shaw BA, Krause N, Bennett JM, Kobayashi E, Fukaya T, Sugihara Y. How does self-assessed health change with age? A study of older adults in Japan. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S224–S232. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Waite LJ. Til Death Do Us Part: Marital Disruption and Mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1131–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM. Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: A hierarchical approach. Demography. 2003;40:309–331. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 2003 Survey of Land and Housing. Tokyo: Nihon Tōkei Kyōkai; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M. Subjective well-being of the urban elderly. Comprehensive Urban Studies. 1990;39:149–159. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M. To Age Happily. Tokyo: Keiso Shobo; 2001. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Population Projections for Japan: 2006–2055. Tokyo: Institute of Population and Social Security Research. (in Japanese); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Latest Demographic Statistics. Tokyo: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. (in Japanese); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai E. The Japanese Family System in Transition: A Sociological Analysis of Family Change in Postwar Japan. Tokyo: LTCB International Library Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa N, Retherford RD. Care of the elderly in Japan: Changing norms and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa N, Retherford RD. Shifting costs of caring for the elderly back to families in Japan: Will it work? Population and Development Review. 1997;23:59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ono H. Divorce, socioeconomic position, and children in Japan relative to the U.S. Paper presented at the conference on “Fertility Decline, Women’s Choices in the Life Course, and Balancing Work and Family Life; Japan, the USA, and other OECD Countries” Tokyo. May 24–25.2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM. The cumlative stratification of the life course. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of Aging and the social Sciences. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996a. pp. 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM. The precious and the precocious: Understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. The Gerontologist. 1996b;36:230–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmore EB, Maeda D. The Honorable Elders Revisited: A Revised Cross-Cultural Analysis of Aging in Japan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo JM, Iwasawa M, Bumpass L. Marital dissolution in Japan: Recent trends and patterns. Demographic Research. 2004;11:395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Nam CB. Living and Dying in the USA: Behavioral, Health, and Social Differentials of Adult Mortality. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Goldsteen K. The impact of the family on health - the decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1059–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update. Stata Journal. 2005;5:188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Shanas E. The family as a social support system in old age. The Gerontologist. 1979;19:169–174. doi: 10.1093/geront/19.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahase S. Hidden Inequality in a Low-Fertility Aging Society. Tokyo: Tokyo University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shirahase S. Luxembourg Income Study Working Paper no.444. Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University; Syracuse, NY: 2006. Widowhood later in life in Japan: Considering social security system in aging society. [Google Scholar]

- Sugisawa H. Social integration and mortality in Japanese elderly. Nihon K shu Eisei Shi. 1994;41:131–139. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama N. Pension reform in Japan at the turn of the century. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance- Issues and Practice. 2001;26:565–574. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S Japan Association of Family Sociology, Committee on National Family Research. National Family Research (NFRJ03) Tokyo: Japan Association of Family Sociology. [in Japanese]; 2005. Sampling design and data characteristics; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:664–674. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2002 Revision. New York: United Nations; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter KW. Kinship resources for the elderly. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1997;352:1811–1817. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. New York: Doubleday; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Hughes ME. At risk on the cusp of old age: Living arrangements and functional status among Black, White, and Hispanic adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1999;54B:S136–S144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.3.s136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC, Menken JA, Bongaarts J. Demographic foundations of family change. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Yamato R. Relationships between support networks and ‘connectedness-oriented’ roles among late-middle-aged Japanese men. Japanese Sociological Review. 1996;47:350–365. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yi Z, Land KC, Wang Z, Gu D. US family household dynamics and momentum-extension of ProFamy method and application. Population Research and Policy Review. 2006;25:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Hayward MD. Childlessness and the psychological well-being of older persons. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56B:311–320. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]