Abstract

Background:

Patient nonattendance in neurology and other subspecialty clinics is closely linked to longer waiting times for appointments. We developed a new scheduling system for residents' clinic that reduced average waiting times from >4 months to ≤3 weeks. The purpose of this study was to compare nonattendance for clinics scheduled using the new model (termed “rapid access”) vs those scheduled using the traditional system.

Methods:

In the rapid access system, nonestablished (new) patients are scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis for appointments that must occur within 2 weeks of their telephone request. Nonattendance for new patient appointments (cancellations plus no-shows) was compared for patients scheduled under the traditional vs the rapid access scheduling systems. Nonattendance was compared for periods of 6, 12, and 18 months following change in scheduling system using the χ2 test and logistic regression.

Results:

Compared to the traditional scheduling system, the rapid access system was associated with a 50% reduction in nonattendance over 18 months (64% [812/1,261 scheduled visits] vs 31% [326/1,059 scheduled visits], p < 0.0001). In logistic regression models, appointment waiting time was a major factor in the relation between rapid access scheduling and nonattendance. Demographics, diagnoses, and likelihood of scheduling follow-up visits were similar between the 2 systems.

Conclusions:

A new scheduling system that minimizes waiting times for new patient appointments has been effective in substantially reducing nonattendance in our neurology residents' clinic. This rapid access system should be considered for implementation and will likely enhance the outpatient educational experience for trainees in neurology.

Outpatient training is a critical component of neurology residency programs.1,2 Studies of neurology residents' clinics have emphasized the need to optimize competency, and have suggested that interventions, such as changes in timing of continuity clinics, may improve experiences for both residents and patients.3,4 Nonattendance, defined as patient-initiated cancellation of an appointment or a no-show, represents an area for improvement.5 Reducing nonattendance in residents' clinics is important for increasing the number and diversity of new patients for evaluation and longitudinal follow-up.

Nonattendance in neurology and other subspecialty clinics has been consistently linked to longer waiting times for appointments.5–10 Studies emphasize the strength of this association across a variety of cultures and health care systems.5–10 In one study of neurology practices in Ireland, factors associated with nonattendance included male sex, age <50 years, urban home address, referral from emergency departments, and >2-month waiting time for the appointment.5 While this relatively long waiting time was associated with greater than double the nonattendance rate, studies in other specialties have shown that waiting times of even 1–2 weeks can make a dramatic difference in nonattendance.6–10

In our US-based academic neurology program, we developed a new scheduling system for residents' clinic that reduced average waiting times for appointments from 4 months to ≤3 weeks. The purpose of this study was to compare rates of nonattendance for clinics scheduled using the new model (termed “rapid access”) vs those scheduled using the traditional system.

METHODS

Under the traditional system for neurology residents' clinic scheduling at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), new patients requested appointments by telephone and were assigned next available appointments. Appointments were scheduled to occur weeks to months later, and clinics were intentionally overbooked to minimize effects of cancellations and no-shows. Patients received phone call reminders 2 business days before appointments.

In July 2006, the new scheduling system, rapid access, was implemented. Using this system, the waiting time for new patient appointments is designed to be ≤3 weeks. Appointments become available each Monday at 8:30 am and are filled on a first-come, first served basis. Once appointments are filled, patients are instructed to call back the following Monday morning. Those who do not receive appointments after calling 3 Mondays in a row are automatically scheduled. Patients receive phone call reminders prior to appointments.

Data were compiled using IDX. Numbers of scheduled new patient visits and proportions not arriving for appointments (nonattendance) were determined for 6, 12, and 18 months prior to and following implementation of the new system. Primary analyses were based on the 18-month data; additional follow-up time also allowed us to determine nonattendance at 36 months. Nonattendance was defined as either a patient-initiated cancellation or a no-show. Proportions of visits with nonattendance were compared using the χ2 test. Logistic regression models were used to assess the relation between traditional vs rapid-access scheduling and nonattendance, accounting for age and appointment waiting time. Type I error was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

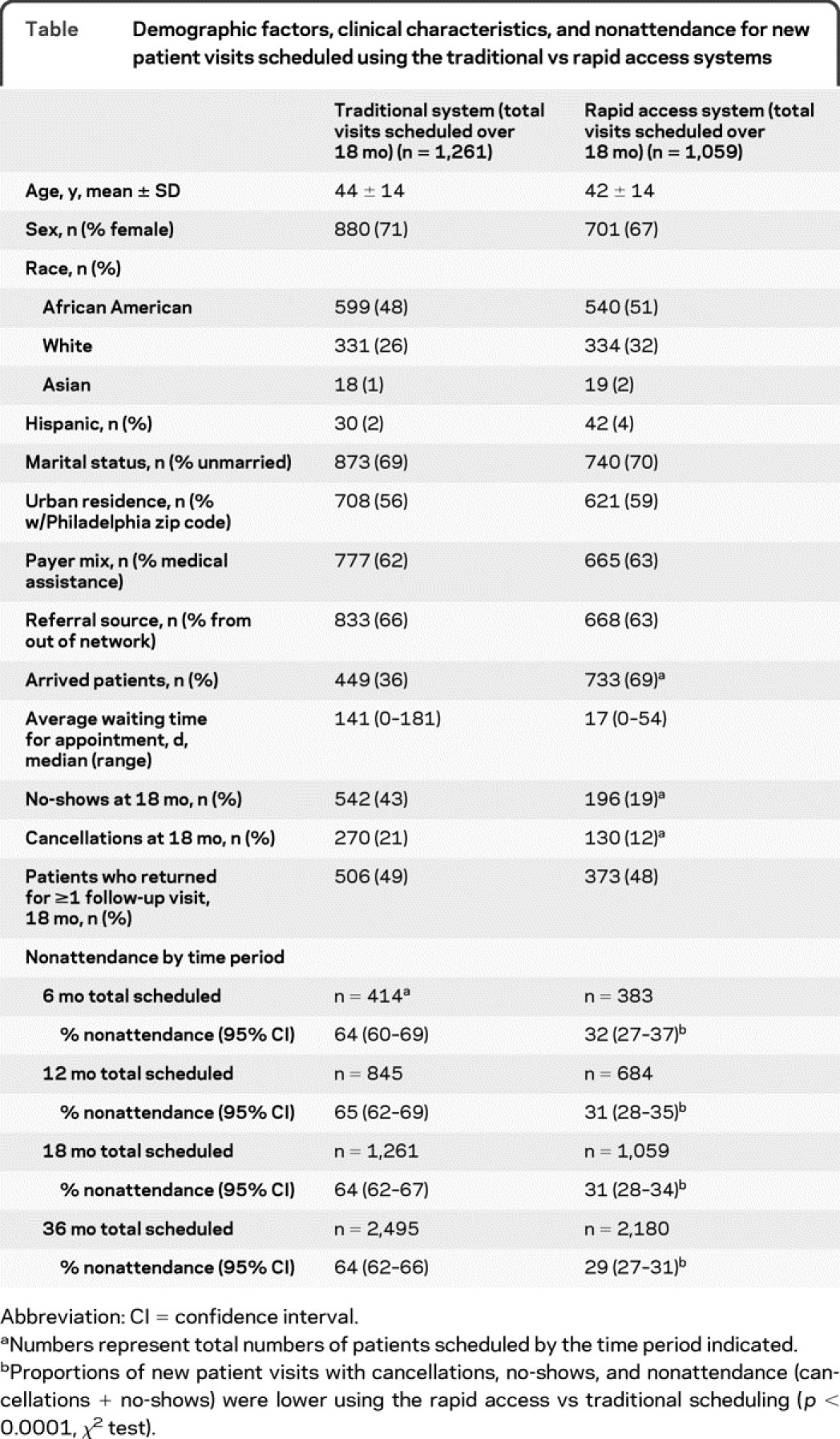

The table presents demographic factors and nonattendance. Age, gender, racial/ethnicity distributions, and diagnoses did not differ between the scheduling systems. The most common diagnoses were headache (20%), epilepsy (19%), and neuromuscular disease (16%). On average, 46% of patients received appointments at the time of their first call to schedule. Average waiting times for new patient appointments were lower for the rapid access system (table). Nonattendance was substantially reduced using the rapid access system (64% vs 31% at 18 months, p < 0.0001, χ2 test). Proportions of patients who returned for at least one follow-up visit did not differ between rapid access and traditional scheduling (table).

Table Demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and nonattendance for new patient visits scheduled using the traditional vs rapid access systems

Nonattendance did not change between 6 and 36 months following implementation of the new system (table). The association between rapid access scheduling and reduced nonattendance was explained by appointment waiting time, as demonstrated by stepwise logistic regression. At 18 months after implementation of the rapid access system, the odds ratio in favor of a visit being rapid access if the patient arrived was 4.1 (95% confidence interval 3.4–4.9, p < 0.001, accounting for age). Accounting for appointment waiting time, the corresponding odds ratio was 1.3 (95% confidence interval 0.97–1.8, p = 0.08), indicating that waiting time is a factor in the relation between scheduling system and nonattendance.

DISCUSSION

Implementation of a system that limits waiting times to ≤3 weeks to schedule a new patient appointment has substantially reduced patient nonattendance in our residents' clinic. Our findings are novel in providing data on nonattendance for a US-based academic neurology practice, and are particularly unique in describing an intervention designed to improve the outpatient experience for neurology residents and their patients.

The rapid access system was developed based on investigations of outpatient clinics in neurology and other subspecialties; these have demonstrated a strong association between longer waiting times and nonattendance.5–10 In one report of a neurology clinic, there was a 50% difference in nonattendance for waiting times >2 months (32%) vs ≤2 months (17%).5 Smaller differences were found for ≥1 vs <1 week in otorhinolaryngology, pulmonary medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology studies (30%–37% nonattendance for >1 week vs 24%–27% for ≤1 week, p < 0.001 for all studies).7–9 We chose a 3-week maximum waiting time for rapid access since it is a practical period for nonurgent scheduling in a medical subspecialty.7–9

Introduction of the new system was not associated with any measurable changes in demographics or diagnoses. Furthermore, patients in both groups were equally likely to return for a follow-up visit. Forty-six percent received an appointment following their first call, and patients were automatically accommodated if they called for 3 consecutive weeks. These numbers are encouraging for an academic program that by definition is limited by the number of resident physicians and by the need to balance patient care excellence with the educational experience. Differences in nonattendance, however, were greater in our study (31% for ≤3 weeks vs 64% for longer waiting times) compared to values in the literature.5–10 This finding is likely due to the fact that our investigation compared nonattendance for 2 different cohorts, and examined nonattendance for periods before and after a change in scheduling system. Although demographics are similar between traditional vs rapid access cohorts, other differences may exist that were not measured.

Our data demonstrate that a new rapid access scheduling system should be considered by neurology training programs for reducing waiting times and patient nonattendance. Such changes will likely improve patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and educational experiences in residents' clinics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. Laura J. Balcer.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Price reports no disclosures. Dr. Balcer served on a scientific advisory board for Biogen Idec; served as a consultant and received speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec and Bayer Schering Pharma; and has received research support from the NIH (K24 EY 018136 [PI]) and from the National MS Society. Dr. Galetta serves on the editorial boards of Neurology® and the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology; served as a consultant for Medtronic, Inc.; serves on a speakers' bureau for Biogen Idec; and has received speaker honoraria from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and Biogen Idec.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Laura J. Balcer, 3 E Gates–Neurology, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104 laura.balcer@uphs.upenn.edu

Study funding: Supported by NIH K24 EY 018136 (L.J.B.).

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gelb DJ. Teaching neurology residents in the outpatient setting. Arch Neurol 1994;51:817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringel SP, Vickry BG, Keran CM, Bieber J, Bradley WG. Training the future neurology workforce. Neurology 2000;54:480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgenlander J, Bushnell C. Education research: neurology continuity clinic: improving the timing of the experience. Neurology 2009;72:e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis LE, King MK, Skipper BJ. Education research: assessment of neurology resident clinical competencies in the neurology clinic. Neurology 2009;73:e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickey W, Morrow JI. Can outpatient non-attendance be predicted from the referral letter? An audit of default at neurology clinics. J R Soc Med 1991;84:662–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penneys NS, Glaser DA. The incidence of cancellation and nonattendance at a dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen AD, Kaplan DM, Shaprio J, Levi I, Vardy DA. Health provider determinants of nonattendance in pediatric otolaryngology patients. Laryngoscope 2005;115:1804–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldbart AD, Dreiher J, Vardy DA, Alkrinawi S, Cohen AD. Nonattendance in pediatric pulmonary clinics: an ambulatory survey. BMC Pulm Med 2009;9:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreiher J, Froimovici M, Bibi Y, Vardy DA, Cicurel A, Cohen AD. Nonattendance in obstetrics and gynecology patients. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2008;66:40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung GM, Castan-Cameo S, McGhee SM, Wong IO, Johnston JM. Waiting time, doctor shopping, and nonattendance at specialist outpatient clinics: case-control study of 6495 individuals in Hong Kong. Med Care 2003;41:1293–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]