Abstract

This study had two goals. The first goal was to see if church-based social relationships are associated with change in self-esteem. Emotional support from fellow church members and having a close personal relationship with God served as measures of church-based social ties. The second goal was to see whether emotional support from fellow church members is more strongly associated with self-esteem than emotional support from secular social network members. The data came from an ongoing nationwide survey of older adults. The findings revealed that having a close personal relationship with God is associated with a stronger sense of self-esteem at the baseline and follow-up interviews. In contrast, emotional support from fellow church members was not associated with self-esteem at either point in time. However, emotional support from secular social network members was related to self-esteem at the baseline but not the follow-up interview.

Introduction

Sociologists as well as psychologists have paid considerable attention to the self-esteem construct. As the vast literature on this core social psychological variable reveals, self-esteem has been used as both an independent and a dependent variable in many studies. For example, a number of researchers suggest that people who feel they belong in a web of lasting and positive social relationships tend to have greater feelings of self-worth (Baumeister and Leary 1995). In fact, belonging to a social group is so important for optimum human development that Maslow (1968) ranked love and belongingness in his widely cited hierarchy of needs. Other investigators have focused on the role self-esteem plays in the maintenance of close interpersonal ties. For example, the sociometer theory that was devised by Leary (2005) specifies that self-esteem is a core part of a psychological system that monitors social relationships for negative cues reflecting disapproval, rejection, or lack of interest on the part of others. When negative cues are detected, people strive to restore social acceptance by using their sense of self-worth to gauge the effectiveness of their restorative efforts. Still other researchers have argued that enhanced feelings of self-esteem are associated with a range of health-related outcomes, including better physical health (e.g., Murrell, Salsman, and Meeks 2003), fewer symptoms of depression (e.g., Fernandez, Mutran, and Reitzes 1998), and a greater probability of adopting beneficial health behaviors, such as regular physical exercise (e.g., Dergance, Mouton, Lichtenstein, and Hazuda 2005). However, some investigators question whether claims regarding these health-related benefits are valid (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger and Vohs 2003). Given the important role that self-esteem plays in social and psychological research, it is important for researchers to derive a better understanding of how people develop and maintain a strong sense of self-worth. A core assumption in the current study is that religion plays an important role in this respect.

Religion and Self-Esteem

Although a wide array of factors that influence self-esteem have been identified in the literature (see Leary and Tangney 2003 for a review of this research), a number of researchers suggest that greater involvement in religion is associated with higher self-esteem (e.g., Relland and Lauterbach 2008). But this literature is complex because religion is a vast multidimensional conceptual domain and as a result, religion may influence self-esteem in a number of ways. For example, Ellison (1993) found that more frequent church attendance and more frequent private prayer are associated with stronger feelings of self-worth among African Americans (see also Francis and Kaldor 2002). Focusing on a different dimension of religion, Krause (2003) reports that older people with a stronger sense of religious meaning in life tend to have higher self-esteem. Several other studies indicate that deep personal identification with religion (as assessed by an intrinsic religious orientation) is also associated with more positive feelings of self-worth (Laurencelle, Abell, and Schwartz 2002). Krause (1995) identified yet another potentially important pathway by linking greater reliance on positive religious coping responses with elevated feelings of self-esteem. Finally, Pargament et al. (1990) found that people who view God in a more positive and benevolent manner have greater feelings of self-worth, as well (see Koenig, McCullough, and Larson 2001 for a review of additional studies linking self-esteem with religion).

The purpose of the present study is to strike out in a different direction by exploring a dimension of religion that has not received sufficient attention in the literature, even though there are sound theoretical reasons for focusing on it – church-based social relationships. It makes sense to examine church-based social ties because social scientists have been arguing for over 80 years that feelings of self-worth arise from the feedback that is provided by significant others. Many attribute this classic insight to Charles Horton Cooley, who devised the notion of the looking glass self. According to Cooley (1927), “We have no means of knowing our self except by observing how others respond to it, and we can be assuredly ourselves only when we have had a long experience of a certain kind of response” (p. 198). As research on the looking glass self continued to evolve, researchers began to tease out some of the finer nuances in this social process. For example, some investigators found that the feedback of some individuals has a greater impact on the self than feedback provided by other individuals (Tice and Wallace 2003). Bock’s research on reference group theory helps ground this notion within the context of religion (Bock, Beeghley and Mixon 1983). According to reference group theory, the attitudes and behaviors of individuals are shaped by the groups in which they participate. But since people may belong to more than one group, it is important to identify the group that carries the greatest weight. Reference group theory specifies that groups will have a greater impact on the individual if the members of these groups have similar status attributes and if they share common values and beliefs. As the empirical findings reported by Bock and his colleagues reveal, involvement with religious groups may have an especially important impact on the individual because they are homogenous with respect to these factors (Bock, Beeghley and Mixon 1983). However, these investigators do not specifically examine the effect of religious groups on self-esteem. Even so, their underlying theoretical framework helps provide a better understanding of why church-based interpersonal relationships are an important source of feelings of self-worth.

A good deal of empirical research highlights the pervasive influence of social relationships on feelings of self-worth. However, much of this work has been conducted outside the context of religion. For example, Krause and Borawski-Clark (1994) report that greater emotional support from family members and close friends is associated with a greater sense of self-esteem. Emotional support may be a particularly effective type of assistance because it involves the provision of empathy, caring, love, and trust. It is not difficult to see why the self-esteem of support recipients would be enhanced when they believe that close others love and care for them. Perhaps this is one reason why a recent longitudinal study by Stinson et al. (2008) reveals that poor quality social bonds predict an acute decline in self-esteem over time.

Recently, a number of investigators have argued that social relationships that arise in the church may be more efficacious than social ties that are found in the wider social world. For example, Krause (2006) found that support from fellow church members effectively offsets the deleterious effects of stress on health, but support from secular social network members fails to provide similar stress-buffering effects. The enhanced benefits of church-based social support have been traced to a number of factors. More specifically, as Krause (2008) points out, the teachings of virtually every major faith tradition extol the virtues of helping people who are in need and forgiving others for the things they have done wrong. In addition, the tenets of the major world religions encourage the faithful to be compassionate and to avoid judging others (Wuthnow, 1991). These support-enhancing attributes are reinforced by the wider social climate of congregations in which fellow church members share a common outlook on life and a collective sense of purpose (Ellison and Levin 1998). If a sense of self-esteem is bolstered and maintained by social relationships, and if social relationships are stronger in religious institutions than in the secular world, then it follows that social relationships that arise in the church may be especially conducive to the development and maintenance of strong feelings of self-worth.

Care must be taken, however, in developing this line of thinking because some investigators argue that providing assistance to others is not necessarily driven by religiously-motivated feelings of altruism. As experimental research by Batson and his colleagues suggests, individuals with either strong extrinsic or strong intrinsic religious motivations are more likely to help others for egoistic rather than altruistic reasons (Batson et al 1989). To the extent that this is true, church-based social support may diminish, rather than bolster, feelings of self-esteem.

Two challenges await investigators who wish to probe more deeply into the relationship between church-based social support and self-esteem. First, research reviewed by Krause (2008) indicates that people often maintain a number of different social relationships in the church. So in order to get a better sense of how feelings of self-esteem arise and are maintained in religious settings, it is important to identify the source or type of social relationship that carries the greatest weight. Second, although the theoretical rationale that has been developed for this study suggests that social relationships in the church may have a more beneficial effect on self-esteem than social ties in the secular world, it is important to back up this claim with empirical evidence.

An effort is made in the analyses that follow to address these challenges by assessing whether three sources of support are associated with greater feelings of self-worth: informal support from fellow church members, developing and maintaining a close personal relationship with God, and informal support from secular social network members. Although the conceptual framework that has been provided above explains why informal support inside and outside the church may be associated with self-esteem, it is important to discuss how developing a personal relationship with God may serve the same self-enhancing function.

In his widely-cited paper, Davidson (1972) identified two key clusters of religious beliefs: vertical and horizontal. Vertical beliefs are especially important for the current study because, as Davidson argues, they “. . . emphasize man’s personal relationships to a supra-empirical being.” (p. 200). The notion of having a personal relationship with God was picked up and elaborated upon by Kirkpatrick (2005) in his work on attachment theory and religion. According to his theoretical scheme, some people who are religious actively seek out and maintain close psychological proximity to God in an effort to extend attachments they formed earlier in life with key caretakers (i.e., typically their parents). Kirkpatrick (2005) goes on to point out that for many of these individuals, God is right there with them physically: “According to most Christian faiths, God (or Jesus) is always on your side, holding your hand and watching over you” (p. 58). And the interpersonal nature of these close ties with God is, in Kirkpatrick’s view, perhaps nowhere more evident than in prayer. More specifically, he maintains that when people pray, they believe they are speaking directly with God, that He hears their prayers, and that He responds directly to them.

Evidence of the real and immediate relationship that some people have developed with God emerged during the formative stages of the current study. The nationwide survey described below was preceded by three years of intense qualitative work (see Krause 2002a for a detailed discussion of this phase of the study). Part of this qualitative research involved conducting a series of open-ended, in-depth interviews. During one in-depth interview, an older woman expressed what it was like to have a close personal relationship with God. She stated that, “I never feel lonely because I know God is here. And I can call on Him and He answers me. He’s right here. I feel his presence . . . He’s with me day and night.” As the interview with this woman reveals, she believes that her relationship with God is real – as real as any relationship she has with other people. If people believe God is right there with them physically, that He is looking over them, and that He directly responds to their requests, then having this kind of close and intimate relationship should go a long way toward shoring up their feelings of self-worth because this type of assistance clearly conveys to the individual that he or she is loved by God and that they are important to Him.

A number of studies have examined the psychosocial correlates of maintaining a close personal relationship with God, but there are limitations in the research that has been done so far. For example, Park, Crocker, and Mickelson (2004) report that having a loving relationship with God is not significantly associated with feelings of self-worth. However, the sample for this study comprised incoming college freshman, making it difficult to determine if the findings can be generalized to more representative samples of adults. Focusing on a different outcome, Kirkpatrick, Shillito, and Kellas (1999) found that college students who feel they have a close personal relationship with God do not feel as lonely as college students who do not have a close relationship with God. Unfortunately, there are two reasons why these findings are limited for the purposes of the current study. First, even though feeling close to God may be associated with loneliness, it is not clear if closeness to God influences feelings of self-worth in the same way (van Baarsen 2002). Second, the fact that this study is also based on college students once again raises issues involving the generalizability of the findings. Mattis and her colleagues found that African Americans who have a positive relationship with God tend to be more optimistic than blacks who do not have a positive relationship with God (Mattis, Fontenot, Grayman, and Beale 2004). However, even though optimism is positively associated with self-esteem (Sweeny, Carroll, and Shepperd 2006), the two constructs are not interchangeable.

An effort is made in the current study to contribute to the literature on religiously-based social relationships and self-esteem in three potentially important ways. First, the data come from a nationwide longitudinal survey. This makes it possible to examine the relationship between church-based social ties and change in self-esteem over time. Second, the participants in this study are older adults. It is especially important to examine the factors that influence feelings of self-worth in this age group because a number of studies suggest that self-esteem tends to decline at an accelerating (i.e., nonlinear) rate through old age (Robins et al. 2002; Trzesniewski, Donnellan, and Robins 2003). Third, an effort is made in the current study to see if the influence of church-based social ties is unique. This is accomplished by comparing and contrasting the effects of relationships inside and outside the church on feelings of self-worth.

Study Model

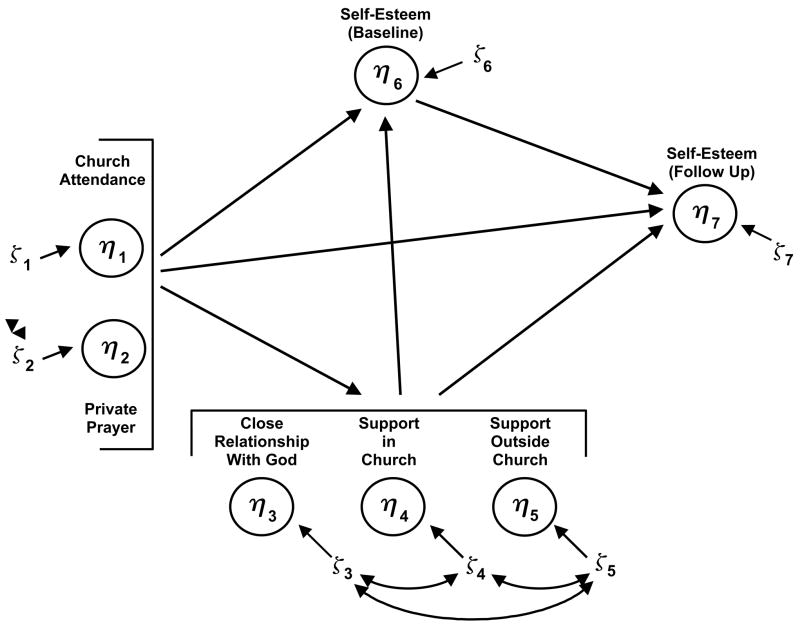

A latent variable model was developed to evaluate the theoretical rationale that was devised for this study. This model, which was empirically evaluated in the analyses presented below, is depicted in Figure 1. Two steps were taken to make this complex model easier to grasp. First, research by McMullin and Cairney (2004) reveals that self-esteem is associated with a range of demographic measures, including age, gender, and social class. Consequently, age, sex, education, and race were in the model that was actually estimated for this study. However, if these demographic measures were included in Figure 1, the model would have become overly complex and difficult to follow. Consequently, this conceptual scheme was simplified by not showing the effects of these demographic measures. Second, in order to make this model easier to read, the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are not shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Church-Based Social Relationships and Change in Self-Esteem

Two major pathways are embedded in this conceptual scheme. First, it is hypothesized that older adults who go to church more often and who pray more frequently will report having a closer relationship with God as well as closer relationships with their fellow church members. If people worship frequently and pray often, then they are likely to subscribe to the tenets of their faith. And because the teachings of the major faiths emphasize the importance of building close relationships with God and their co-religionists (Davidson, 1972), then engaging in prayer and formal worship services should be associated with closer ties to God and better relationships with fellow church members. However, it is further specified in Figure 1 that prayer and attendance at formal worship services will also exert a positive influence on the relationships that older adults maintain with people outside of church. The tenets of the major faith traditions advocate helping not only fellow church members, but individuals who do not share the same faith. In fact, a premium is placed in the Christian faith on helping strangers (recall the biblical story of the good Samaritan, but see the study by Batson et al. 1989). If older adults adhere to the practices of their faith, then church teachings about helping others should spill over into the relationships with people outside of church. To the extent this is true, more frequent church attendance and more frequent prayer should foster closer ties with secular social network members, as well.

The second major pathway in Figure 1 hypothesizes that people who have closer relationships with their fellow church members, a closer relationship with God, and closer ties with people outside of church will have a greater sense of self-worth. There are, however, two corollaries to this general proposition. First, it is proposed that social ties with fellow church members and with God will have a greater impact on self-esteem than social ties with secular network members. Recall the research that was discussed earlier which suggests that church-based social ties may be more efficacious than social relationships in the wider secular world (Krause 2006). Second, an effort is made to bring the element of timing to the foreground by seeing how long it takes for the effects of these social relationships on self-esteem to become manifest. On the one hand, better social ties may enhance feelings of self-worth relatively quickly. This is captured by the path leading from the social relationship constructs to the baseline measure of self-esteem. This is known in the literature as a contemporaneous effect. But an equally important issue involves whether social relationships are associated with feelings of self-worth at the follow-up interview. This is known as a lagged effect. In essence, this lagged effect involves the relationship between social ties and change in self-esteem over time.1 By simultaneously testing for contemporaneous and lagged effects, it is possible to derive greater insight into the nature of the relationship between church-based social ties, secular social ties, and feelings of self-worth in late life.

Method

Sample

The data for this study come from an ongoing nationwide survey of older Whites and older Blacks. The study population was defined as all household residents who were either Black or White, noninstitutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age. Geographically, the study population was restricted to all eligible persons residing in the coterminous United States (i.e., residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded). Finally, the study population was restricted to currently practicing Christians, individuals who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and people who were not affiliated with any faith at any point in their lifetime.

The sampling frame consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A five-step process was used to draw the sample from the CMS Files (see Krause 2002b).

The baseline survey took place in 2001. The data collection for all waves of interviews was performed by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1,500 interviews were completed, face-to-face, in the homes of the study participants. Elderly Blacks were over-sampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess race differences in religion. As a result, the Wave 1 sample consisted of 748 older Whites and 752 older Blacks. The overall response rate for the baseline survey was 62%.

The Wave 2 survey was conducted in 2004. A total of 1,024 of the original 1,500 study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 75 refused to participate, 112 could not be located, 70 were too ill to participate, 11 had moved to a nursing home, and 208 were deceased. Not counting those who had died or moved to a nursing home, the re-interview rate for the Wave 2 survey was 80%.

A third wave of interviews was completed in 2007. A total of 969 older study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 33 refused to participate, 118 could not be located, 17 were too sick to take part in the interview, and 155 older study participants had died. Not counting those who had died, the re-interview rate was 75%.

The analyses presented below are based on the data from the second and third waves of interviews. These interviews were selected because questions on support provided by people outside the church were administered for the first time at Wave 2.

The number of cases that were available for analysis presented below were influenced by two factors. First, it did not make sense to ask study participants questions about support they receive from fellow church members if they either never go to church or if they go to church only once or twice a year. Consequently, these low-attenders (N = 342) were excluded from this analyses that were conducted for this study. Second, the available sample size was further reduced by the use of listwise deletion procedures to deal with item nonresponse (90 cases had missing values). After taking these issues into account, the analyses that follow are based on the responses of 537 older study participants. Preliminary analysis of the sample that was used in the analysis for this study reveals that 36.8% are older men and 45.9% are older Whites. The average age of the respondents in this group at Wave 2 was 76.6 years (SD = 5.6 years). Moreover, the study participants reported at Wave 1 that they had successfully completed an average of 12.0 years of schooling (SD = 3.3 years). These descriptive statistics, as well as the findings that are presented below, are based on data that have been weighted. These weights were derived in the following manner. Within each racial group, the cases were weighted so they match the age, gender, and education reported in the most recent census data.

Measures

Table 1 contains the core measures that are used in the analyses presented below. The procedures used to code these items are provided in the footnotes of this table.

Table 1.

Core study measures

|

These items are scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): never (1); once in a while (2); fairly often (3); very often (4).

These items are scored in the following manner: strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); agree (3); strongly agree (4).

This item is scored in the following manner: never (1) ; less than once a year (2); about once or twice a year (3); several times a year (4); about once a month (5); 2 to 3 times a month (6); nearly every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

This item was scored in the following manner: never (1); less than once a month (2); once a month (3); a few times a month (4); once a week (5); a few times a week (6); once a day (7); several times a day (8).

Emotional support from fellow church members

As shown in Table 1, emotional support provided by co-religionists is assessed with three items that were devised by Krause (2002a). A high score on these measures indicates that older study participants receive support from fellow church members more often. These measures come from the Wave 2 interviews.

Emotional support from secular social network members

Three indicators were also used to assess how often people outside the church provide support to older study participants. These measures come from the work of Krause (2002a). In order to maximize the comparability of the church-based and secular support items, the question stems differ only with respect to the source of support. The following introduction to these items was provided to study participants before the questions were administered, “Now I have some questions about people who do not attend your church”. A high score on this brief composite represents more frequent support.

Close personal relationship with God

Three questions were used to assess whether older study participants feel they have a close personal relationship with God. These indicators were developed by Krause (2002a). A high score denotes closer ties with God.

Self-esteem

Items assessing feelings of self-worth were administered in the Wave 2 and Wave 3 surveys. These indicators were taken from the widely used scale devised by Rosenberg (1965). A high score on these indicators represents greater feelings of self-worth.

Church attendance

Based on the work of Ellison (1993), a measure was included in the Wave 2 survey to determine how often older study participants attend formal worship services. A high score on this indicator denotes more frequent church attendance.

Private prayer

Study participants were also asked at Wave 2 how often they pray when they are by themselves. A high score on this item reflects more frequent private prayer.

Demographic control variables

The relationships among the variables in Figure 1 were evaluated after the effects of age, sex, race, and education were controlled statistically. Age is a continuous variable. Education is also a continuous variable that reflects the total number of years of schooling that were completed successfully by older study participants. In contrast, sex (1 = men; 0 = women) and race (1 = whites; 0 = blacks) are scored in a binary format.

Results

Assessing the Effects of Sample Attrition

As the discussion of the study sample reveals, some older people who were interviewed at Wave 2 did not participate in the Wave 3 survey. Some investigators argue that the loss of subjects over time may bias study findings if it occurs in a nonrandom manner (Little and Rubin 2002). Although it is difficult to conclusively determine the extent of this problem, some preliminary insight may be obtained by seeing whether select data from the Wave 2 survey are associated with study participation status at Wave 3. The following procedures were used to address this issue. First, a nominal-level variable consisting of three categories was created to represent older adults who participated in both the Wave 2 and Wave 3 surveys (scored 1), older people who were alive but did not participate at Wave 3 (scored 2), and older adults who died during the course of the follow-up period (scored 3). Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this categorical outcome was regressed on the following Wave 2 measures: age, sex, education, race, the frequency of church attendance, the frequency of private prayer, having a close personal relationship with God, emotional support from fellow church members, emotional support from secular social network members, and self-esteem. Evidence of potential bias might be found if any statistically significant findings emerge from this analysis.

The results (not shown here) reveal that only one of the ten Wave 2 measures significantly differentiated between older adults who were alive but did not participate in the study and older people who took part in both waves of interviews. More specifically, the data suggest that compared to people who remained in the study, those who dropped out but were still alive were more likely to be women (b = −1.137; p < .05; odds ratio = .321). The findings further indicate that compared to older people who remained in the study, respondents who died tended to be older (b = .057; p < .05; odds ratio = 1.059), they were more likely to be men (b = 1.108; p < .001; odds ratio = 3.027), they had fewer years of schooling (b = −.095; p < .05; odds ratio = .909), and they prayed less often when they were alone (b = −.299; p < .05; odds ratio = .742).

Even though the analyses suggest that the loss of subjects over time did not occur in a random manner, there are two reasons why the study findings may not have been affected adversely. First, the data suggest there are variations in participation status by age, sex, and education. However, as Graham (2009) pointed out recently, because these variables are included in the latent variable model as covariates, potential bias that is associated with the is likely to be minimal. Second, an extensive review of the literature by Groves (2006) reveals that nonresponse does not necessarily translate into nonresponse bias. This means that even though nonrandom patterns of attrition were observed in the data, it does not necessarily follow that the relationships among study variables are biased. Even so, the potential influence of this nonrandom pattern of subject attrition should be kept in mind as the substantive findings from this study are examined.

Assessing the Fit of the Model to the Data

The model depicted in Figure 1 was evaluated with the maximum likelihood estimator in Version 8.71 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit and du Toit 2001). However, use of this estimator is based on the assumption that the observed indicators in a study model have a multivariate normal distribution. Preliminary tests (not shown here) revealed that this assumption had been violated in the current study. Although there are a number of ways to deal with departures from multivariate normality, the straightforward approach that is provided by du Toit and du Toit was followed here. These investigators report that departures from multivariate normality can be handled by converting raw scores on the observed indicators to normal scores prior to estimating the model (du Toit and du Toit 2001, p. 143).

Self-esteem is measured at two points in time. Consequently, two important issues involving the measurement of this construct must be addressed so that the model with the best fit to the data can be identified. The first has to do with seeing whether the measurement error terms for identical indicators of self-esteem are correlated over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) reveal that the measurement error terms are significantly correlated over time. The second issue has to do with assessing factorial invariance over time (Bollen, 1989). Test for factorial invariance assess whether the elements of the factor loadings and measurement error terms are the same over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) indicate that the factor loadings and the measurement error terms are invariant over time.

The fit of the final model to the data is good. More specifically, the Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (Bentler and Bonett 1980) estimate of .963 is well above the recommended cut point of .900. Similarly, the standardized root mean square residual estimate of .029 is below the recommended ceiling of .050 (Kelloway, 1998). Finally, Bollen’s (1989) Incremental Fit Index value of .983 is quite close to the ideal target value of 1.0.

Psychometric Properties of the Observed Indicators

Table 2 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from estimating the study model. These coefficients provide preliminary information about the psychometric properties of the multiple item study measures. Kline (2005) recommends that items with standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have reasonably good reliability. As the data in Table 2 indicate, the standardized factor loadings range from .582 to .957. Only one coefficient was below .600, and the difference between this estimate (.582) and the recommended value of .600 is trivial. Consequently, it appears that the measures that are used in this study have good psychometric properties.

Table 2.

Measurement error parameter estimates for multiple item study measures (N = 537)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Support From Fellow Church Members (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Love and Care for youc | .833 | .306 |

| B. Listen to your private concerns | .623 | .612 |

| C. Express interest and concern | .873 | .237 |

| 2. Emotional Support From Secular Social Network Members (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Love and care for you | .765 | .415 |

| B. Listen to your private concerns | .582d | .661 |

| C. Express interest and concern | .868 | .246 |

| 3. Close Personal Relationship with God (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Close personal relationship with God | .867 | .249 |

| B. God right here with me | .905 | .180 |

| C. God listens to me | .886 | .214 |

| 4. Self-Esteem (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Person of worth | .872 | .239 |

| B. Number of good qualities | .957d | .083 |

| C. Positive attitude toward self | .871 | .241 |

| 4. Self-Esteem (Wave 3) | ||

| A. Person of worth | .867 | .247 |

| B. Number of good qualities | .956 | .087 |

| C. Positive attitude toward self | .866 | .250 |

Factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed at 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the .001 level.

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification. See Table 1 for the complete text of each indicator.

The second- and third-listed items were constrained to be equivalent in the unstandardized solution for identical Wave 2 and Wave 3 self-esteem measures.

Although the factor loadings and measurement error terms associated with the observed indicators provide useful information about the reliability of each item, it would be helpful to know something about the reliability for the scales as a whole. Fortunately, it is possible to compute these reliability estimates with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This procedure is based on the factor loadings and measurement error terms in Table 2. Applying the procedures described by DeShon yields reliability estimates for the multiple item constructs in Figure 1: emotional support from fellow church members (.824), emotional support from secular social network members (.788), having a close personal relationship with God (.917), self-esteem at Wave 2 (.928), and self-esteem at Wave 3 (.925). Taken as a whole, these estimates suggest that the items used in the current study have an acceptable level of reliability.

Substantive Findings

The substantive findings from this study are provided in Table 3. These data provide support for a number of the key study hypotheses, but there are some unanticipated results as well. As hypothesized, the data reveal that older people who go to church more frequently report they have a closer relationship with God than older adults who do not go to worship services as often (Beta = .103; p < .05). Moreover, the results suggest that older people who attend worship services more often tend to receive more emotional support from their fellow church members than older adults who do not go to church as frequently (Beta = .229; p < .001). But in contrast, the frequency of church attendance is not associated with emotional support that is received from secular social network members (Beta = .011; ns).

Table 3.

The relationship between social support, feelings of closeness to god, and change in self-esteem (N = 537)

| Dependent Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Church Attendance | Private Prayer | Close with God | Church Support | Secular Support | Self-esteem (Wave 2) | Self-esteem (Wave 3) |

| Age | −.034a (−.008)b | .024 (.005) | −.062 (−.005) | −.045 (−.006) | −.068 (−.006) | −.137*** (−.011) | −.036 (−.003) |

| Sexc | −.016 (−.047) | −.200*** (−.451) | −.070 (−.064) | −.036 (−.055) | −.031 (−.034) | .056 (.053) | .056 (.052) |

| Education | .010 (.004) | −.063 (−.020) | −.051 (−.007) | −.070 (−.015) | −.050 (−.008) | .119** (.016) | .093* (.012) |

| Raced | .063 (.174) | −.143** (−.313) | −.078 (−.069) | −.138** (−.205) | .085 (.090) | −.080 (−.074) | −.067 (−.060) |

| Church attendance | .103* (.033) | .229*** (.123) | .011 (.004) | .017 (.006) | .057 (.019) | ||

| Private prayer | .323*** (.130) | .283*** (.193) | .266*** (.129) | −.061 (−.026) | −.041 (−.017) | ||

| Close with God | .440*** (.464) | .147** (.151) | |||||

| Church support | −.077 (−.048) | .057 (.035) | |||||

| Secular support | .128* (.112) | .060 (.051) | |||||

| Self-esteem (Wave 2) | .128* (.125) | ||||||

| Multiple R2 | .006 | .075 | .169 | .209 | .082 | .239 | .096 |

Standardized regression coefficient (i.e., beta coefficients)

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

(1 = men; 0 = women)

(1 = white; 0 = black)

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001.

A similar but more extensive pattern of findings emerges with respect to private prayer. The data in Table 3 indicate that older people who pray more often tend to have a closer relationship with God (Beta = .323; p < .001), they report receiving more emotional support from fellow church members (Beta = .283; p < .001), and they receive more emotional support from secular social network members (Beta = .266; p < .001). Taken as a whole, these data reveal that public and private religious practices are associated with the nature of the relationships that older people develop both inside and outside of church.

The data in Table 3 indicate that the relationships that are formed and maintained by older people, in turn, influence their feelings of self-worth. More specifically, the data suggest that having a close relationship with God is strongly associated with self-esteem at Wave 2 (Beta = .440; p < .001). And in addition to this, having a close and personal relationship with God also tends to bolster feelings of self-worth over time (i.e., at Wave 3; Beta = .147; p < .05).

In contrast to the findings involving a personal relationship with God, the data in Table 3 reveal that emotional support provided by fellow church members does not appear to influence the self-esteem of older people at either Wave 2 (Beta = −.077; ns) or Wave 3 (Beta = .057; ns). An effort was made to delve more deeply into these surprising findings by exploring the bivariate correlations between the latent construct representing support provided by fellow church members and the latent measures of self-esteem at Wave 2 ( r = .104) and Wave 3 ( r = .141; unfortunately, the LISREL software program does not provide tests of statistical significance for these coefficients). Viewed more broadly, these data suggest that support from fellow church members may initially appear to be associated with feelings of self-worth, but this association is no longer statistically significant once the relationship that older people have with God is taken into account.

The results in Table 3 also suggest that emotional support provided by secular social network members is associated with self-esteem at Wave 2 (Beta = .128; p < .05), but these beneficial effects are not sustained over time to Wave 3 (Beta = .060; ns).2 Because having a close relationship with God and support for secular social network members both affect feelings of self-worth at Wave 2, it would be helpful to know if there is a statistically significant difference in the size of these relationships. An additional test was performed by seeing whether the fit of the model to the data changes (i.e., deteriorates) significantly after the two estimates were constrained to be equivalent. This test revealed that the effect of having a close relationship with God on feelings of self-worth at Wave 2 is significantly larger than the influence of emotional support received from secular social network members (chi-square change = 20.961 with 1 df; p < .001).3

Conclusion

The self-esteem motive is one of the fundamental postulates in social psychology (Kaplan 1975). According to this perspective, the need to develop and maintain a positive sense of self-worth is one of the primary motivating forces in social life and as a result, it shapes a good deal of human behavior. If people have an innate need to develop and maintain a strong sense of self-esteem, then they are likely to seek out sources of self-worth in many different quarters. The goal of the current study was to suggest that involvement in religion may be one place that people turn to in an effort to satisfy this basic need.

A conceptual model was tested which suggests that religion may affect feelings of self-worth in two ways. Both pathways are based on the premise that the genesis of self-esteem may be found in the social relationships that people develop. The first pathway proposed that public and private religious practices (i.e., attendance at worship services and private prayer) are associated with having closer social ties. The data suggest that older adults who go to church more often tend to have a closer relationship with God and receive more support from the people in their congregations than older people who do not go to church as frequently. However, the frequency of church attendance was not associated with support received from secular network members. In contrast, older adults who pray more often when they are alone say they have a closer relationship with God and they report receiving more support from their co-religionists as well as their secular network members. So of the two religious practices that are examined in this study, private prayer seems to have more far-reaching effects. Although data were not available to conclusively determine why this may be so, one possibility may involve the level of religious commitment that lies behind these two religious practices. Perhaps people who pray when they are alone are more committed to their faith than individuals who attend worship services. And if the teachings of the church encourage the development of close social ties, then it is reasonable to expect that people with the greatest commitment to their faith will be more likely to incorporate these religious doctrines in their daily lives.4

The second major pathway in the conceptual model that was developed for this study suggests that having a close personal relationship with God, receiving emotional support from fellow church members, and receiving emotional support from secular social network members will bolster self-esteem in late life. The findings suggest that of the three types of social relationships, the strongest and most consistent associations involve the influence of having a close personal relationship with God. More specifically, the data indicate that having a close personal relationship with God is associated with greater self-esteem at both the baseline and follow-up surveys. In contrast, receiving support from fellow church members was not related to self-esteem at either point in time, and emotional support from secular network members was related to self-esteem at the baseline but not the follow-up interviews. Viewed more generally, these data indicate that the effect of social relationships on self-esteem tends to be manifest fairly quickly rather than being lagged.

Greater confidence can be placed in these results because the current study has three main strengths. First, the data are longitudinal. Second, the sample is comprised of a nationwide survey of older adults. Third, the analyses were performed with sophisticated latent variable modeling procedures that take the effect of random measurement error into account.

It is important to reflect on the meaning of the findings involving the three social relationship measures. Two issues are critical in this respect. The first involves explaining why having a close personal relationship with God is more important than either of the other social relationships. Some insight is provided by Kirkpatrick (2005). He suggests that many religious people believe that God is a source of unconditional love and unwavering support. Although human beings may also be a source of love and support, it seems less likely that most people will feel this love is unconditional, and it seems less likely that the majority of individuals will feel this support will be forthcoming no matter what happens. If self-esteem arises from the perceived feedback of others, then the source that provides the most consistent and unrestricted positive feedback is likely to carry the greatest weight in this process.

The second finding in this study is more difficult to explain. It was hypothesized that emotional support from fellow church members would have a greater effect on the self-esteem of older people than emotional support from secular social network members. However, this hypothesis was not supported by the data.5 One possibility may involve the way church-based emotional support is measured in this study. These measures ask about emotional support that is provided by all the members of a congregation taken together. However, some church members may play a greater part in bolstering self-esteem than others. This possibility is illustrated in a recent study by Krause and Cairney (2009) that involves close companion friends at church. Close companion friendships typically arise in dyads and are characterized by a high degree of intimacy, self-disclosure, and trust. Moreover, close companion friends share things they value highly and encourage personal growth in each other (Krause, 2008). Although measures of close companion friendships at church are available in the current study, they were not used in the analyses presented above for three reasons. First, the model for this study was designed to compare and contrast church-based with secular social support. Unfortunately, questions on support from close companion friends in secular networks were not in the data. Second, 64 percent of the older people in this study who attend church on a regular basis report having a close companion friend in their congregation. Including measures of companion friends in the current study would have limited the analyses to a more restricted subgroup of study participants. Third, the measures of church-based companion friends were administered for the first time in the Wave 3 survey. Because only three waves of data have been collected for this study so far, longitudinal analysis of change in self-esteem over time would not have been possible.6

Although the findings from the current study may provide some useful insights into the ways in which religion bolsters self-esteem in late life, a good deal of work remains to be done. As research by Krause (2008) reveals, a complex web of different types of social relationships may be found in the church. However, a number of these relationships were not examined in the current study, including support from the clergy as well as participation in formal roles in the church, such as performing volunteer work. Clearly, the relationships between these dimensions of church-based social ties and self-esteem should be evaluated.

The most important findings to emerge from this study involved having a personal relationship with God. Although this appears to be the first time that relationships with God have been linked with self-esteem, it would be helpful to probe more deeply into this relationship by exploring the images that older people have of God. The items that are used in the current study focus on whether older adults have a close relationship with God, whether they feel God is with them in daily life, and whether God listens when they speak to Him. However, these indicators do not fully capture the affective nature of this relationship. It might be important to focus on this affective component because having an image of God as loving may be more likely to bolster feelings of self-worth than having an image of God as controlling (see Wiegand and Weiss, 2006, for a recent discussion of God images).

The measure of self-esteem that was used in this study assesses feelings of self-worth in general. However, as William James (1892/1961) argued some time ago, people play many different roles and as a result, there are multiple selves and potentially different evaluations of each one. James went on to argue that some selves are more important than others: “So the seeker of his truest, strongest, deepest self must review the list carefully and pick out the one on which to stake his salvation. All other selves thereupon become unreal, but the fortunes of this self are real” (p. 53). It would be intriguing to assess how religion affects the different selves that people maintain, especially those that are the most salient to them. In addition, it would be interesting to see whether people maintain a separate religious self, and if they do, it would be important to determine if religious constructs such as having a close personal relationship with God have a greater effect on the religious self than on another dimension of the self, such as the self that is associated with the role of parent or grandparent (for a discussion of matching different selves with performances and experiences in different life domains see Swann, Chang-Schneider and McClarty, 2007).

In the process of assessing these issues, researchers should to pay careful attention to the limitations in the current study. Three shortcomings are reviewed below. First, even though the data were gathered at more than one point in time, it is not possible to conclusively state that developing a close personal relationship with God subsequently “causes” stronger feelings of self-worth. One might just as easily argue that people with initially high levels of self-esteem are able to maintain a deeper relationship with God because they feel they are more worthy of it. It is also not possible to conclusively state that close emotional relationships with other people bolsters feelings of self-worth. Instead, it could be argued that older adults with a strong sense of self-worth subsequently have closer emotional relationships with their significant others. However, in this instance, there is some evidence that the direction of causality in the current study may have been specified correctly. Two experimental studies by Leary (2003) reveal that study participants who obtained social approval subsequently experienced increased feelings of self-worth. The second limitation in the current study arises from the fact that people who attend church on a regular basis are likely to differ in a number of ways from individuals who do not go to church often. One of these differences is especially important for the purposes of this study. It is not possible to rule out the prospect that individuals with a strong sense of self-worth are more likely to attend church on a regular basis than people with a weaker sense of self-esteem. If this is true, then this self-selection bias may have adversely influenced the study findings. Third, the sample for this study comprises people who are either Christian or individuals who do not identify with any faith tradition. Consequently, it is not possible to tell if the findings can be generalized to individuals of different faiths (e.g., Jewish people or Muslims).

Even though the current study may be improved in a number of ways, it is hoped that the model and the findings that have been presented motivate other investigators to delve more deeply into the ways in which the church may shape feelings of self-worth in late life. The link between religion and self-esteem was recognized some time ago by Cooley (1927), who noted that, “So long as one can keep faith in God he will not lose self-respect; and those who respect themselves have always some sort of faith in God” (p. 251). The task that awaits researchers who study the social and psychological foundations of religion is to show why this may be so.

Footnotes

The lagged effect of an independent variable, such as having a close relationship with God, on self-esteem at Wave 3 controlling for self-esteem at Wave 2 may also indicate that a close relationship with God sustains feelings of self-worth over time. Unfortunately, the analyses that must be performed to disentangle the effects of constructs that are associated with change in self-esteem from constructs that sustain self-esteem over time is beyond the scope of the current study (for a discussion of these procedures see Kessler and Greenberg 1981).

It is possible that support from secular network members may influence self-esteem at Wave 3 indirectly through self-esteem at Wave 2. Estimates of this indirect effect is provided by the LISREL software program. The data suggest that the indirect effect of emotional support from secular network members on self-esteem at Wave 3 that operates through self-esteem at Wave 2 is: Beta = .016; ns.

The questions on church-based social support were only administered to study participants who attend church more than twice a year. This may create a problem if older people who go to church more often may place a greater emphasis on church-based social ties because religion is more salient to them while older people who are not regular attenders place a greater emphasis on secular social support. To the extent that this is true, the effects of secular support may be underestimated. This issue was evaluated by assessing the relationship between secular support and change in self-esteem for older people who attend church twice a year or less (N = 156). The data suggest that the effect of secular support on change in self-esteem for older non-attenders is not statistically significant.

A preliminary test of this perspective was conducted by examining the correlations between the frequency of church attendance, the frequency of private prayer, and a brief three-item index that assesses a person’s level of commitment to his or her faith (e.g., “I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my other dealings in life”). These indicators come for the intrinsic religious motivation scale devised by Hoge (1972). The data suggest that the relationship between more frequent private prayer and religious commitment ( r = .345; p < .001) is stronger than the correlation between the frequency of church attendance and religious commitment ( r = .090; p < .05).

The church-based emotional support items are comprehensive measures that ask how often someone in the congregation provides this type of assistance. In contrast, the secular support indicators ask about emotional support that is provided specifically by family members and friends. Since people often worship with family members, there may be some overlap between the two social support measures. There are two ways to address this concern. First, the correlation between the two latent social support constructs is .498. This means that there is approximately 25% shared variance between these measures while 75% of the variance is unique. This suggests the two constructs appear to measure different things. Second, and perhaps more important, the nationwide survey was preceded by three years of intensive qualitative work (see Krause 2002a). During the course of the focus groups and in-depth interviews that comprised this phase of the project, participants were asked if they considered their spouse or children to be fellow church members or family members. The participants consistently said they view their spouse, children, and other relatives as family members.

A preliminary test of this argument was conducted with the Wave 3 data only. Bivariate correlations were computed for the relationship between the measures of church-based close companion friends that were devised by Krause (2008), measures of emotional support from fellow church members, and measures of self-esteem. The data suggest that close companion friends at church have a stronger relationship with self-esteem (r = .301; p < .001) than emotional support from all members of the congregation taken together (r = .169; p < .001).

References

- Batson CD, Oleson KC, Weeks JL, Healy SP, Reeves PJ, Jennings L, Brown T. Religious prosocial motivation: Is it altruistic or egoistic? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:873–884. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4:1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bock EW, Beeghley L, Mixon AJ. Religion, socioeconomic status, and sexual morality: An Application of reference group theory. Sociological Quarterly. 1983;24:545–559. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Life and the student: Roadside notes on human nature, society, and letters. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JD. Patterns of belief at the denominational and congregational levels. Review of Religious Research. 1972;13:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dergance JM, Mouton CP, Lichtenstein MJ, Hazuda JP. Potential mediators of ethnic differences in physical activity in older Mexican American and European Americans: Results from the San Antonio Longitudinal Study on Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1240–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP. A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M, du Toit S. Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. Religious involvement and self-perception among Black Americans. Social Forces. 1993;71:1027–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez ME, Mutran EJ, Reitzes DC. Moderating effects of stress on depressive symptoms. Research on Aging. 1998;20:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Francis LJ, Kaldor P. The relationship between psychological well-being and Christian faith and practice in an Australian population sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge DR. A validated intrinsic religious motivation scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1972;11:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- James W. Psychology: The briefer course. New York: Harper & Row; 18921961. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB. Self-attitudes and deviant behavior. Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear Publishing Company; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg D. Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA. Attachment, evolution, and the psychology of religion. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Shillito DJ, Kellas SL. Loneliness, social support, and perceived relationships with God. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1999;16:513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religiosity and self-esteem among older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1995;50B:P236–P246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.p236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002a;57B:S263–S274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring race differences in a comprehensive battery of church-based social support measures. Review of Religious Research. 2002b;44:126–149. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S160–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based social support and secular social support on health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006;61B:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Borawski-Clark E. Clarifying the functions of social support in late life. Research on Aging. 1994;16:251–279. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Cairney J. Close companion friends in church and health in late life. Review of Religious Research. 2009 (In Press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencelle RM, Abell SC, Schwartz DJ. The relation between intrinsic faith and psychological well-being. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2002;12:109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. The invalidity of disclaimers about the effects of social feedback on self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:623–636. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029005007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology. 2005;16:75–111. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tangney JP. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Fontenot DL, Grayman NA, Beale RL. Religiosity, optimism, and pessimism among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:187–207. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JA, Cairney J. Self-esteem and the intersection of age, class, and gender. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004;18:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Murrell SA, Salsman NL, Meeks S. Educational attainment, positive psychological mediators, and resources for health and vitality in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2003;15:591–615. doi: 10.1177/0898264303256198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Ensing DS, Falgout K, Olsen H, Reilly B, Van Haitsma K, Warren R. God help me I: Coping efforts as predictors of outcomes to significant negative events. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:793–824. [Google Scholar]

- Park LE, Crocker J, Mickelson KD. Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1243–1254. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relland S, Lauterbach D. Effects of trauma and religiosity on self-esteem. Psychological Reports. 2008;102:779–790. doi: 10.2466/pr0.102.3.779-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Tracy JL, Gosling SD, Potter J. Global self-esteem across the lifespan. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:423–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson DA, Logel C, Zanna MP, Holmes JG, Cameron JJ, Wood JV, Spencer SJ. The cost of lower self-esteem: Testing a self and social bonds model of health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:412–428. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Chang-Schnieder C, McClarty KL. Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept in everyday life. American Psychologist. 2007;62:84–94. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeny K, Carroll PJ, Shepperd JA. Is optimism always best? Future outlooks and preparedness. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Wallace HM. In: Handbook of self and identity. Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Stability of self-esteem across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:205–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baarsen B. Theories of coping with loss: The impact of social support and self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and social loneliness following a partner’s death in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002;57B:S33–S42. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand KE, Weiss HM. Affective reactions to the thought of God: Moderate effects of the image of God. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. Acts of compassion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]