Abstract

The present study examines the associations between Mexican American mothers’ and fathers’ pregnancy intentions, fathers’ participation in prenatal activities and mother-infant interactions and father engagement with 9 month-old infants in a nationally representative sample of 735 infants and their parents participating in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort. After controlling for a host of variables, multiple regressions revealed that when mothers wanted the pregnancy, fathers engaged in more literacy and caregiving activities than when mothers did not want the pregnancy. When couples disagreed about wanting the pregnancy, fathers engaged in more literacy activities and showed more warmth than when they agreed. Relationship quality significantly moderated the effects of parents’ wantedness on mother-infant interactions and fathers’ engagement in literacy activities.

Keywords: pregnancy intentions, mother-child interactions, parent involvement

INTRODUCTION

Although recent studies have shown that Latino fathers are involved in caregiving and child care of their children (Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006; Hofferth, 2003), there are virtually no studies on the circumstances of birth (such as wanting the pregnancy) and its effects on later parenting behaviors among Mexican American parents. Studies of mostly European American, married couples suggest that parents’ desire for a pregnancy as well as fathers’ prenatal behaviors (e.g., attending doctor’s visits) are important influences on the quality of parents’ later affective and behavioral involvement with their children and on child functioning (Baydar; 1995; Brown & Eisenberg, 1995; Cabrera, Fagan, & Farrie, in press; Fagan, Bernd, & Whiteman, 2007; Palkovitz, 1985). Whether these links are similar for Mexican American families is unknown. Lack on research on this population is problematic given that Latinos in the U.S. are a heterogeneous group that makes up about 12.5% of the total population. Two-thirds of Latinos are Mexican Americans and are reported to be largest and poorest ethnic group in the U.S. (U.S. Census, 2000). Although the majority of Mexican Americans are legal immigrants or native-born citizens (Cauce & Rodriguez, 2001), they, particularly recent immigrants, are more likely to be economically disadvantaged than European Americans. A national study found that Mexican American parents whose babies were born in 2001 are poorer, have less education, have larger families, are younger, and are less likely to be married than non-Latino infants living in two-parent families (Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). Consequently, extant research on Mexican American families generally confounds parenting processes with socioeconomic status (SES) and levels of acculturation, which make it difficult to interpret findings. Thus, examining how parents’ desire for the pregnancy and father prenatal behaviors at the transition to fatherhood relate to positive later parenting behaviors, after accounting for SES, may provide some empirical basis for the development of preventive measures for families of this ethnic group who are at risk.

The current study poses three research questions: (1) Controlling for child and parent characteristics, including education and income, and level of acculturation, how do Mexican American fathers’ and mothers’ wantedness of the pregnancy influence mother-infant interactions and father engagement with their infants? (2) How do couples’ agreement on wanting the pregnancy and fathers’ prenatal involvement additionally affect parenting behaviors?; (3) Does mother-father relationship quality moderate the association between wanting the pregnancy and mother-infant interaction and father engagement? We address these questions using attachment theory that parents’ desire to have a baby influences their ability to be responsive and engaged with their infants. We draw from a national sample of Mexican American infants who participated in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), which collects detailed information on a sample of children born in 2001 directly from their mothers and fathers.

Mothers’ and Fathers’ Prenatal Attitudes and Parenting Behaviors

An important consideration in reviewing the literature on prenatal attitudes, especially unintended pregnancies, is the issue of measurement. Unintended pregnancies are conventionally defined as pregnancies that are unwanted (not desired) or mistimed (occurred earlier than desired). On the other hand, intended pregnancies are reported as occurring at the “right time” or later than desired (Henshaw, 1998). However, this definition confounds two separate aspects of fertility, wantedness and timing, which may have different implications for parent-child relationships. Thus, Santelli and colleagues (2003) suggest using separate measures of wantedness and timing. In this paper, we focus only on wanting the pregnancy because a third of the sample of fathers was not asked about the timing of the pregnancy.

The empirical literature based on attachment theory shows that the feelings and thoughts parents have about their children, even before birth, are linked to the quality of later parenting and that these processes are universal (Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991; Weiss, 1974). Parents who desire their children are engaged and responsive to their infants’ communicative signals, which form the basis for children’s sense of security and trust in others and a belief that they are worthy of that trust (Ainsworth, 1969, 1973). The bond that parents form with their infants is critical for sensitive and responsive parenting (Ainsworth, 1973). Mothers and fathers who do not want the pregnancy may have a difficult time bonding with their child, which can lead to reduced engagement or negative parenting and ultimately to child maladjustment (Lamb, 1997).

Research on the effects of wanting a pregnancy on parenting behaviors has focused mostly on mothers in married couples or on fathers alone. The bulk of these research findings indicate that parents who want their pregnancy feel parenting is joyous, have authoritative parenting styles, accept their children, have positive relationships with them, and are more likely than other parents to spend time with and provide emotional support for their children, which results in positive outcomes for children (Cabrera et al., in press; Bronte-Tinkew, Ryan, Carrano, & Moore, 2007; Koreman, Kaestner, & Joyce, 2002; McLanahan & Carlson, 2001; Zuravin, 1991). Also, fathers who want the pregnancy may feel they have more control over contraception and birth planning and as a result have less conflict with their partners, and are more involved, and show more economic responsibility for their child than other fathers (Bachrach & Sonenstein, 1998; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2004). These studies, however, are less clear about at what point in development these effects emerge.

Other studies show mixed findings. In a study of racially diverse mothers, Baydar (1995) found that while mistimed children experienced more authoritarian parenting than wanted children, intentionality did not affect their mothers’ warmth and responsiveness toward them. More recently, Ispa, Sable, Porteer and Csizmadia (2007) found no association between low-income African American mother’s acceptance of the pregnancy (degree of happiness about being pregnant) and maternal warmth, but they found that lack of maternal pregnancy acceptance predicted toddler’s attachment security and mothers’ feeling that parenting is burdensome. However, it is possible that once the baby is born, some parents who had not wanted the pregnancy may become loving and engaged with their infant but feel a burden later in the child’s life as parenting becomes more resource-intense and challenging. These issues are difficult to discern due in part to the fact that most often these data are collected retrospectively. It is also plausible that mothers’ acceptance of the pregnancy may have little effect on her parenting behavior because of social and cultural expectations that mothers must be responsive and caring to their children.

Research on Mexican American families has often emphasized the high cultural value of the family, which is often large and is a source of emotional support for individual members, who feel loyal to it, experience reciprocity and solidarity with its members, and are highly attached to each other (Cuellar, Arnold, & Gonzales, 1995). In turn, family solidarity has been linked to good prenatal outcomes, grandmother support for child care, quality of parenting, and positive school outcomes for middle-school children (see Harwood, Leyendecker, Carlson, Asencio, & Miller, 2002 for review). This research is generally based on convenient samples, has focused on mothers, has highlighted the stress and psychological hardship related to the immigration experience, has emphasized ethnic differences as deficits, and has confounded culture with SES and levels of acculturation (Buriel, 1993; Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004; Garcia Coll, 2002; Toth & Xu, 1999). As a result, we have limited information about parenting processes in this population, in particular how the circumstances of birth (wanting a baby) are linked to later parenting behaviors at the transition to fatherhood, which can place men in a trajectory of more or less involvement (Buriel, 1993; Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004; Garcia Coll, 2002; Toth & Xu, 1999). Moreover, the importance of gender roles in the process of making important decisions (e.g., fertility) is unknown, especially as it relates to later parenting behaviors. Although research has shown that Spanish-speaking Mexican American couples with high fertility hold pronatalist values whereas English-speaking Mexican American appear to use a low fertility strategy (Sorensen, 2008), it is unclear how men and women pronatalist values are linked to their parenting behaviors. In a cultural context that generally prescribes nurturing roles to mothers and instrumental role to fathers, one would expect high parental involvement in their respective roles regardless of personal desire to have a child. This is an area of research that has received little attention. It has not considered how mothers’ and fathers’ personal preference to have a baby plays out in a cultural context where parents feel a strong connection to the family and value children.

Drawing from the extant research and guided by the universality of attachment theory, it is expected that Mexican American fathers and mothers who want the pregnancy are more likely to be engaged and interact with their infants than those parents who do not. On the other hand, Latino cultural beliefs about the value of children and family might trump personal desire to have a baby. This area of research is largely unexplored. Given this review, we do not hypothesize about the association between intentionality and parental behaviors.

Couples’ Relationship Quality, Agreement about Pregnancy, and Parenting

Robust empirical findings on mostly white European samples on the effects of quality of partner relationship on parenting behaviors have shown that the quality of mother-father relationship is significantly associated with parenting (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004). This process is not well understood for Mexican American samples. In general, studies of Mexican American families are scarce, findings are inconsistent, and have focused on parenting roles rather than on interparental relationships. Earlier research on Mexican American families suggest that parental authority, children’s obedience, and respect for parents are major values within the Mexican American families (Solis-Camara & Fox, 1995). The view that Mexican American mothers are traditionally the primary caretakers and fathers the disciplinarians is changing in light of new evidence suggesting that this style of parenting may be more related to socioeconomic status than ethnicity per se and may change as families become acculturated (Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2002; Fox & Solis-Camara, 1997). However, less is known about how the mother-father relationship among Mexican American families influences parenting behaviors or child wellbeing. In one recent study, marital problems had a direct effect on child adjustment but the path was not through parenting style as it was for the non-Latino whites (Parke et al., 2004). In another study of Mexican-American two-parent families, researchers found that partner conflict was negatively related to fathering quality with teen children (Formosa, Gonzalez, Barrera, & Dumka, 2006). The inconsistent findings might be attributable to diversity in measurement of father involvement as well as reflect developmental differences in the effects of relationship quality on parenting.

A potential source of conflict among couples that may affect parenting behavior is disagreement about wanting the pregnancy. If the pregnancy is unwanted by one partner and not the other, it may negatively affect how parents interact with their children. Nevertheless, there are very few studies that consider whether parents’ agreement to have a child relates to parenting behaviors (Koreman et al., 2002), and the few existing studies focus on maternal and infant health outcomes. For example, a study of pregnant women found that pregnancies that were intended by mothers, but unintended by fathers had the greatest risk for women’s postpartum depression (Leathers & Kelley, 2000). In another study of a national sample of youth, Koreman and his colleagues (2002) showed that when both parents wanted the pregnancy their infant had better health outcomes than when the father did not desire pregnancy. The reverse was not true; they found no evidence that a child whose conception was unintended by the mother had worse health outcomes than when both parents intended the pregnancy (Koreman et al., 2002). These findings suggest that couple disagreement over the pregnancy can have negative effects on maternal and infant health, but that it matters which parent does not want the pregnancy. Worse outcomes were reported when the fathers did not want the pregnancy. An explanation might be that fathers who do not want the baby may be less supportive and therefore a source of stress for the mother. However, this study relied on mother report of fathers’ intentions, which has limitations (Cabrera et al., 2002), and it did not consider how fathers’ relationship with their partner might moderate this association. It is possible that even when fathers do not want the baby, they will be more supportive if they are happy with their partners.

Studies of couples’ agreement to have a baby among Latinos are particularly scarce. We found one study that examined the influences of Latino fathers’ intentionality on mothers’ prenatal care. Findings showed that, especially for married couples, pregnancies unintended by mother but intended by father had a lower likelihood of delayed prenatal care compared to pregnancies that were unintended by both parents (Sangi-Haghpeykar, Mehta, Posner, & Poindexter, 2005). Although this study did not include data on intentionality reported by the fathers themselves and did not examine parenting behaviors, these findings, coupled with earlier findings, suggest that father’s desire (to want or not to want the pregnancy) might be more important for certain outcomes than mother’s desire to have a baby. A possible explanation might lie in the cultural expectations of parents that define Latino fathers’ role as provider and women’s role as caretaker (Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004). Hence, Latino father’s desire of the pregnancy would have a significant effect on his provider role, which may result in less stress and more positive parenting for mothers. Again, it is not clear how these processes might change with partner relationship quality nor is there literature on whether father’s wanting the baby would affect other aspects of father involvement such as engaging in caregiving, expressing warmth to the child, or engaging in activities that promote learning such as reading, singing songs, etc. (Cabrera et al., 2007). Given the scant literature we cannot hypothesize about the direction of the association between Mexican American couple’s agreement on wantedness and their parenting behaviors or whether or not partner relationship quality would moderate this association.

Fathers’ Prenatal Involvement and Father Engagement

Prenatal involvement has been conceptualized in terms of men’s support for the mother (e.g., buying supplies, taking her to doctor’s visits) and in terms of men’s experiences directly with the unborn child (e.g., examining an ultrasound, listening to the fetus’ heart). Palkovitz’s (1985) review of the literature on father’s prenatal involvement provides no conclusive evidence that it is directly related to improved father-child interaction. However, recent research based on datasets with improved methodological and conceptual frameworks finds that early involvement before and during the birth of the child is significantly linked to later paternal engagement (Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley, & Roggman, 2007; Cabrera et al., in press; Fagan et al., 2007; Shannon, Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, & Lamb, 2003). At the transition to fatherhood, fathers who are prenatally involved are more likely to be involved with their children later on because they are committed to their fathers’ roles and their partners (Cabrera et al., 2007; Elder, 1998). We know of no studies conducted with Latino samples that explore prenatal behaviors and its effects on parenting. One study of low-income fathers whose children were enrolled in Early Head Start found that most Latino fathers were highly involved in prenatal behaviors (Shannon et al., 2003, see Tamis-LeMonda, this volume). Based on this scant evidence, we cannot hypothesize about the direction of the association between Mexican American fathers’ prenatal involvement and later parenting involvement.

Control Variables

Variation in mother-child interactions and father involvement has been related to a host of sociodemographic variables including mothers’ and father’s age at first birth, education, employment, income, race and ethnicity, acculturation, number of other children and relationship status in addition to child characteristics (e.g., age, gender). The father’s age at the birth of his first child is related to his ability to provide for his child and thus stay involved in his child’s and partner’s life (Pleck, 1997). Also, mother’s education and acculturation has been found to be highly predictive of mother-infant interaction quality and father engagement (Cabrera et al., 2006; Ispa et al., 2007). Research has shown that fathers who are employed and have higher levels of education are more likely to live with their children or to exhibit positive parenting behaviors than less educated, unemployed fathers, although the evidence for this is mixed (Cook et al., 2005; Fagan, Barnett, Bernd, & Whiteman, 2003; Grant, Duggan, Andrews, & Serwint, 1997). Moreover, women’s age and employment as well as the couple’s earlier relationship status and the quality of the partner relationship may encourage union formation, cohabitation, or marriage (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2002), which are associated with higher levels of father involvement. Although evidence is mixed, some studies find that fathers are more involved with their sons than daughters (Easterbrooks & Goldberg, 1984; Kelley, Smith, Green, Berndt, & Rogers, 1998). In this study, to isolate the independent effects of parents’ wanting the pregnancy and prenatal involvement on father involvement, we control for these variables.

METHOD

Participants

We used data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), the first study in the United States designed to track a nationally representative sample of children, including Latinos, from birth into school (NCES, 2005a). The ECLS–B collects demographic and parenting data on mothers and fathers in addition to children’s outcomes (cognitive, social, and physical) at 9 months, 24 months, preschool entry, and first grade. The current study draws on data collected at Wave 1, the base-year (9-month). The base-year ECLS-B sample consists of 10,688 infants and includes 2,193 children whose mothers identified them as Latino. Two-thirds of these Latino children (67%) were identified by their mothers as Mexican American. The other third (33%) were identified as members of different Latino ethnic groups, including Puerto Rican, Central American, and Dominican.

Overall, about 74% of all ECLS-B children’s mothers completed a parent computer-assisted interview, as did about 72% of Latino children’s mothers. Child assessments were completed for 96% of the total sample of ECLS-B children whose mothers had completed the interview and for 95% of the Latino children whose mothers completed the interview. Because nearly all children lived with their biological mothers at 9 months of age and most lived with their biological fathers (78%), we decided to limit the sample used in our analyses to infants living with both biological parents.

To understand the selective nature of our sample of Latino infants with resident biological parents (i.e., married and cohabiting; n = 1,711) compared to Latino infants residing in other family structures (i.e., single parent, and non-biological married or cohabiting parents; n = 482), we examined whether maternal sociodemographic, mental health, and contextual characteristics (e.g., acculturation, depressive symptoms, mother-infant interactions) and infant cognition differed by family structure. Married and cohabiting biological Latino mothers had higher household incomes [t (2,192) = 8.69, p < .01], were older [t (2,192) = 9.02, p < .001), and were more educated [χ2 (2, N = 2,193) = 23.18, p < .01] than were mothers from other family structures. They also reported less depressive symptoms, more family support, and more happiness in their relationships with their partner than did those mothers who did not reside with their child’s biological father [ts (2,192) range = 4.63 to 4.73, ps < .001]. However, the number of children in the household, the mothers’ English proficiency, reports of the level of conflict with their spouse or partner, the quality of mother-infant interactions, and infants’ scores on the mental scale of the Bayley-Short Form Research Edition did not differ by family structure. These differences and similarities should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings.

At 9 months, 76% of the all ECLS-B infants’ resident fathers and 65% of Latino infants’ resident fathers completed a questionnaire that asked about their involvement with their children. A nonresponse bias analysis that compared the characteristics of children, their mothers, and fathers using data from birth certificates and from the ECLS-B mother interview showed few differences between responding and nonresponding resident fathers for the full ECLS-B sample. Moreover, the few differences found between these groups were corrected by adjustments to the sampling weights (Bethel, Green, Kalton, & Nord, 2005). To further determine the selectivity of our sample of Latino infants and their biological, resident mothers and fathers, we compared certain characteristics of infants with participating fathers (n = 1,099) to those of Latino infants with nonparticipating fathers (n = 605). Participating infants’ fathers were more likely to be married [χ2 (1, N = 1,704) = 5.17, p < .05] and better educated [χ2 (2, N = 1,704) = 12.69 and 29.87, ps < .05], less likely to be working [χ2 (1, N = 1704) = −12.16, p < .001], and lived in households with fewer number of children [t (1702) = −3.42, p < .05] than nonparticipating fathers. Also, mothers of participating fathers engaged in more positive interactions with their infants and were less likely to report conflict with their partners, ts (1,702)= 2.74 and 2.13, ps < .05 than nonparticipating mothers. Parents’ age, mothers’ employment status, English proficiency, family support, and depressive symptoms as well as infants’ scores on the NCAST did not differ by father participation.

The Latino sample in the ECLS-B consisted of 1,099 Latino infants (735 Mexican American and 364 other Latino infants) who had at least one Latino parent (e.g., 88% of mothers and 89% of fathers identified themselves as Latino), who lived with both biological parents, whose mothers completed a parent interview, whose fathers completed a resident father questionnaire, and who were administered the child assessment at approximately 9-months of age. The final analytic sample for this study consisted of 735 Mexican American infants and their resident, biological parents. On average, Mexican American infants were 10 months (range: 8.2 to 12.8 months), with more than half (55%) were boys.

Procedure

The ECLS–B collected data on mothers, fathers, and children when the children were on average 9, 24, 48, and 60 months of age. During home visits, trained field staff conducted a computer-assisted interview with mothers, assessed infants’ mental and physical development, and videotaped mother–infant interactions. Mother–infant interactions were videotaped for 4 to 5 ½ min during a semi-structured teaching task. Following the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale protocol (NCATS; Sumner & Spietz, 1994), mothers were asked to select and teach their infants a new activity from a list of age-appropriate activities (e.g., banging two blocks together, turning pages in a book).

In 99% of the cases, the respondent to the parent interview was the child’s biological mother. The remaining parent interviews were completed with other female guardians or with children’s fathers. If the spouse or partner of the mother lived in the same household as the ECLS–B child, he was asked to complete a self-administered resident father questionnaire. In most cases (98%) the respondent to the father questionnaire was the child’s biological father (NCES, 2005a). The remaining questionnaires were completed mostly by other male household members (e.g., child’s grandfather), and in very few cases by another female living with the child. Respondents were interviewed in the language of their choice. All ECLS-B instruments were translated into Spanish and responses translated back to English (Bethel, et al., 2005).

Measures

Outcome Variables

Mother-infant interactions

The quality of mother-infant interactions was assessed from videotapes using the NCATS (Sumner & Spietz, 1994). The NCATS employs a binary scale (0 = not observed, 1 = observed) of 50 parent items to measure critical aspects of mother and child behavior that takes place during a semi-structured teaching task. It provides information on mother’s sensitivity to the child’s clues, responsiveness to the child’s distress, cognitive growth fostering, and socioemotional growth fostering. Tapes were checked for quality and coded by a group of certified NCATS coders using the using procedures described in NCES (2005a). Coders whose scores fell below 85% agreement with the University of Washington NCATS staff members were not allowed to continue coding until they had completed coding additional reliability tapes and once again reached or exceeded the 85% criteria. Coders of caregiver – infant interactions were fluent in the language of the dyads. Coders were unaware of mothers’ scores on the mental health and contextual measures, fathers’ engagement, and infants’ cognitive scores.

A total parent score was calculated by summing the 50 parent items. Possible scores range from a low score of 0 to a high score of 50. Higher scores indicated more positive and responsive maternal interactions. The total parent score demonstrated adequate internal consistency for this sample with a coefficient alpha of .70. The alpha level for the full ECLS-B sample was .68 (NCES, 2005a).

Father engagement

Given the scope of this study, we focus on father engagement as opposed to other aspects of involvement such as accessibility and responsibility, because engagement is better measured in the ECLS-B and has been linked to child outcomes (Black, Dubowitz, & Starr, 1998; Lamb, Pleck, & Chernov, 1987; Tamis-LeMonda, Shannon, Cabrera, & Lamb, 20004). Specifically, in the current study fathers were asked to rate how frequently they engaged in three types of activities with their infants (i.e., literacy, caregiving, and warmth). For the literacy subscale, fathers were asked to rate how frequently (4-point Likert scale) they engaged with their infants in a typical week in the following literacy activities: reading books, telling stories, and singing songs (α = .70). For the caregiving subscale, fathers were asked to rate how frequently the engaged in the following caregiving activities in the past month: preparing meals or bottles, feeding the children, putting their children to sleep, washing or bathing their children and dressing their children (α = .84). For the warmth subscale, fathers were asked to rate (on 6-point Likert scale) how often they engaged in the following activities in the past month: tickling their children and blowing on their bellies, and holding their children (r = .44). Each subscale was transformed into z-scores using the weighted-mean and standard deviation for the Latino sample.

Moderator Variables

Mother-father relationship quality

To rate the quality of parents’ relationships with their partners, both mothers and fathers were asked one general question about their overall happiness in their relationship. Parents were asked to rate how happy they were in their marriage/relationship on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = not too happy to 3 = very happy). As the majority of mothers and fathers rated their relationship as very happy (73% and 69% for mothers and fathers, respectively), these variables were dummy-coded as 0 (not happy or somewhat happy) or 1 (very happy).

Explanatory Variables

We use mothers’ and fathers’ own reports of whether they wanted the pregnancy to examine associations with parenting behaviors. We do not include timing of pregnancy because it is highly correlated with wanting the pregnancy and because in the ECLS-B approximately 30 percent of parents who reported not wanting the pregnancy were not asked questions about the timing of the pregnancy. Given the literature on marital interaction, we examine mothers’ and fathers’ desire for the pregnancy separately. Drawing from the Dynamic Model (Cabrera et al., 2007), we also examined the effects of father prenatal involvement on parenting behaviors.

Mothers’ and fathers’ intentionality

Mothers and fathers were asked whether the pregnancy was wanted or not (Mother wanted pregnancy = 1, Mother did not want the pregnancy = 0; Father wanted pregnancy = 1, Father did not want the pregnancy = 0). Based on parents agreement or disagreement about wanting the baby, a new couple agreement variable was created reflecting parents’ agreement/disagreement (1 = mother and father both agreed to either want or not want the pregnancy, 0 = only one parent wanted the pregnancy).

Prenatal involvement

Fathers were asked about their prenatal involvement across seven items: “Did you see a sonogram?”, “Did you listen to baby’s heart beat?”, “Did you feel the baby move?”, “While mother was pregnant, did you buy things for the baby(ies)?”, “Did you discuss the pregnancy with child’s mother?”, “Did you attend a birth or Lamaze class with child’s mother?”, and “Did you see baby in the hospital/birthing center?” All items were coded 0 = no, 1 = yes.

Controls

Mothers’ and fathers’ sociodemographic characteristics

Information was gathered from mothers on family structure (e. g., married, cohabitation, single parent), parents’ ages, educational attainment (i.e., 1 = less than high school, 2 = completed high school, 3 = more than high school), employment status (1 = working, 0 = not working), as well as annual household income (i.e., 0 = $14,999 or less, 1 = $15,000–29,999, 2 = $30,000–49,999, 3 = $50,000–74,999, 4 = $75,000 or more) and the number of children living in the household.

Child characteristics

Infants’ birth certificates, which provided information on children’s gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy), and date of birth, were used to calculate infants’ ages at the time of the home visit. During the 9-month mother interviews, if mothers identified their infants as Latino, they were also asked whether their infant was of Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or other Latino ancestry.

English Proficiency

Acculturation is generally described as the process of adapting and adjusting beliefs, behaviors, and values as a result of interacting with a host culture (Berry, 1990). It is most commonly measured in terms of language facility and use, length of residency in host country, and generation status (Buriel, Calzada, & Vasquez, 1988; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Wong-Rieger, & Quintana, 1987). Although this index of acculturation is preferred, some studies have shown that English language proficiency is a robust indicator of acculturation because it is associated with length of residence (Arcia, Skinner, & Bailey, 2001). In this study we use a measure parents’ proficiency in English because the ECLS-B does not have generational status of the mothers at 9 months. Both parents were asked how well they speak, read, write, and understand English using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = very well to 4 = not very well at all) if English was not the primary language. These four proficiency items were recoded (1 = very well; 0 = pretty well to not very well at all) and summed to create an index of proficiency for each parent. Mothers and fathers reporting that English was the primary language in the home received a 4 on the index. Since the majority of mothers and fathers obtained scores of 0 or 4 on this index (47% and 46% for mothers; 47% and 50 % for fathers), this variable was dummy-coded as 0 (scores of 0 to 2; less proficient) and 1 (scores of 3 or 4; more proficient).

Data Analytic Strategy

We first describe couples’ socio-demographic characteristics, prenatal attitudes (wantedness), fathers’ prenatal involvement, mother-father relationship quality (i.e., mother-reported happiness, father-reported happiness), mother-infant interactions and father-reported engagement (literacy, caregiving, and warmth) in a national sample of Mexican American and other-Latino infants born in 2001 and their parents (See Table 1 and Table 2). Next, the study hypotheses were tested using hierarchical multiple regression. Four series of hierarchical models with mother-infant interaction quality and fathers’ engagement (literacy, caregiving, and warmth) as the outcome variables were constructed. The first models in each regression included the socio-demographic control variables (i.e., infant gender and age, household income, mother and father education, hours employed, age and English proficiency, number of children in the household, and marital status) entered together in step one since they have been associated with mother and father engagement (see Cabrera et al., 2006; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004). Mother-and father-reported happiness were entered simultaneously in step two. In the second models, the explanatory variables (i.e., mother and father wanting the pregnancy and couple agreement) were added as a set in step three.

Table1.

Non-Latino and Latino Infants in Two-Parent Families by Country of Origin

| Variables | All Non- Latinos |

All Latinos a | F/χ2 | Mexican Americans |

Other Latinos | F/χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 6,682 | N = 1,099 | n = 735 | n = 364 | |||

| M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% | |||

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Married | 87% | 71% | 123.42*** | 71% | 71% | 0.00 |

| Number of Children (including own children, nieces, nephews, etc.) |

1.91(.79) | 1.99(.82) | 2.56** | 2.07(.82) | 1.79(.79) | 3.85*** |

| Annual Income (%) | 362.53*** | 46.67*** | ||||

| <$15K | 8% | 22% | 26% | 12% | ||

| $15K – 30K | 18% | 36% | 37% | 34% | ||

| $30K – 50K | 23% | 24% | 25% | 20% | ||

| $50K – 75K | 21% | 9% | 7% | 15% | ||

| >$75K | 30% | 9% | 5% | 19% | ||

|

Mother Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Education Level (%) | 476.32*** | 40.76*** | ||||

| Less Than High School | 14% | 49% | 57% | 28% | ||

| Completed High School | 21% | 20% | 17% | 28% | ||

| More Than High School | 65% | 31% | 26% | 44% | ||

| Age at Interview (M) | 29.66(5.86) | 27.54(5.70) | 9.18*** | 27.07(5.71) | 28.73(6.67) | −3.31** |

| Employed (%) | 55% | 43% | 38.97*** | 39% | 54% | 12.79*** |

| Father Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Education Level (%) | 517.01*** | 57.32*** | ||||

| Less Than High School | 12% | 48% | 58% | 25% | ||

| Completed High School | 23% | 21% | 19% | 26% | ||

| More than High School | 65% | 31% | 23% | 49% | ||

| Age at Interview (M) | 32.09(6.42) | 30.10(6.56) | 7.80*** | 29.63(6.24) | 31.30(7.19) | −2.41* |

| Employed (%) | 93% | 82% | 88.97*** | 80% | 88% | 6.28*** |

| Infant Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (M) | 10.18(1.34) | 10.21(1.41) | .56 | 10.15(1.36) | 10.36(1.51) | −1.70 |

| Male (%) | 51% | 53% | .90 | 55% | 47% | 3.51** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Note: Table is cited in Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006.

Table 2.

Relationship Quality, Prenatal Attitudes and Involvement, Mother-Infant Interaction and Father Engagement: Mexican American and other-Latinos

| Mexican Americans | Other Latinos | F/χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 735 | n = 364 | ||

| Variables | M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% | |

| Relationship Quality (%) | |||

| Mom reporting very happy | 73% | 70% | 1.18 |

| Dad reporting very happy | 69% | 70% | .01 |

| Wantedness of Pregnancy(%) | |||

| Mom wanted the pregnancy | 58% | 61% | 1.78 |

| Dad wanted the pregnancy | 76% | 75% | .09 |

| Both agreed to want or NOT want the pregnancy | 58% | 62% | 1.00 |

| Both disagreed about wanting the pregnancy | 42% | 38% | 1.00 |

| Mom wanted the pregnancy and Dad did NOT | 28% | 30% | .08 |

| Dad wanted the pregnancy and Mom did NOT | 72% | 70% | .08 |

| Father Prenatal Involvement (%) | |||

| Visual perception of child | |||

| See sonogram of baby | 89% | 94% | 4.38* |

| See heartbeat of baby | 91% | 90% | .32 |

| Feel baby move | 98% | 97% | .52 |

| Mother support during pregnancy | |||

| Buy things for mother during pregnancy | 94% | 96% | 1.22 |

| Discussed pregnancy with mother | 75% | 86% | 14.28*** |

| Attended Lamaze or other birthing class | 31% | 35% | 1.80 |

| Visited baby and mother at birth | 98% | 99% | 1.05 |

| Mother-Infant Interaction | 32.92(4.39) | 34.77(4.23) | 32.61*** |

| Father Engagement | |||

| Literacy (z score) | .00(1.01) | .00(.97) | 0.01 |

| Caregiving (z score) | .03(.99) | −.07(1.03) | 1.35 |

| Warmth (z score) | −.04(1.04) | .10(.88) | 4.10* |

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Note: Possible scores on the mother-infant interaction scale range from a low score of 0 to a high score of 50.

To test for moderation, we followed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) steps. We first created interaction terms by multiplying each of the dichotomous explanatory variables (mother wanted, father wanted, couple agreement) by mother- and father-reported happiness. Then, in the fourth step of each series of hierarchical regression models we alternatively entered three pairs of interaction terms, one pair for each explanatory variable (e.g., mother wanted × mother-reported happiness and mother wanted × father-reported happiness) (not shown). For any significant interaction term, we plotted mean scores on the outcome variable for each level of the explanatory and moderating variables.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to running analyses, confirmatory factor analysis with father prenatal involvement variables and tests for collinearity were run. A confirmatory factor analysis with two factors only accounted for 40% of the variance in the seven prenatal items. The two factors only had cronbach’s alphas of .39 and .19 for visual knowledge of child (3 items) and support of mother (3 items), respectively. When fathers’ responses to the seven items were summed to create an overall index of fathers’ prenatal involvement the Cronbach alpha was still low (α = .44). Fathers were highly engaged in 6 out of the 7 prenatal activities (percentages ranged from 75% to 98%). Given poor reliability of this measure and because there was little variability in father prenatal involvement, we excluded prenatal involvement from our regression models. We only report descriptive statistics for prenatal items. Tests for collinearity (the correlation matrix is available from the authors) revealed no evidence of collinearity among any of the explanatory variables.

Descriptive Analyses

We highlight several descriptive findings for both Mexican American and other-Latino infants and their parents (see Table 1 and Table 2). Approximately a quarter of both groups of Latinos (196 Mexican-Americans and 63 other-Latinos) lived in modest circumstances (between 30,000 and 50,000 dollars of family income per year) and almost one-quarter of both groups of Latinos (201 Mexican-Americans and 37 other-Latinos) lived in very poor circumstances (less than 15,000 dollars of family income per year), with more Mexican-Americans being poor (F = 46.67, p > .001). About half of infants’ mothers and fathers had not completed high school, with the rate being twice as high in the Mexican-American (447 mothers and 455 fathers) as the other-Latino (88 mothers and 78 fathers) families. The infants who were Mexican-American had parents who were younger, had more children, and were more likely to be unemployed than the infants who were from other-Latino country descent. About one-half of the parents were English proficient. Fewer Mexican-American infants had English proficient parents than infants with other Latino country descent, mothers: 45% (n = 356) versus 67% (n = 208); fathers: 41% (n = 300) versus 63% (n = 185).

About 70% of the parents in both ethnic groups (555 Mexican-American and 218 other Latino) were married as opposed to cohabiting (the marriage rate is lower for all Latino parents than for the total population of ECLS-B families (F = 123.42, p < .0001). The majority of Mexican American parents [73% (n = 497) mothers and 69% (n = 528) fathers], reported being very happy in their relationship with their partner. Similar levels of happiness were reported for mothers (70%; n = 189) and fathers (71%; n = 212) from other Latino origin. The majority of Mexican American mothers (57%; n = 313) and fathers (76%; n = 572) reported wanting the pregnancy. Parents of other Latino origin reported similar rates, 61% of mothers (n = 131) and 75% of fathers (n = 229). However, fathers from both Latino groups reported wanting the baby more often than did mothers (ts = 6.71 and 3.83, ps < .001). Moreover, approximately 58% (n = 303) of Mexican American couples and 62% (n = 133) of couples of other Latino origin were in agreement about wanting the pregnancy (either wanted it or not wanted it). Of the 42% of Mexican American couples in disagreement about wanting the baby, fathers more frequently wanted the baby when mothers did not want the baby (72% versus 28%, respectively, t = 7.15, p < .001). These are notable strengths of these families.

Almost all fathers in both groups of Latinos were engaged in prenatal behaviors that measure visual knowledge of child (e.g., see a sonogram, listen to baby’s heart beat, feel the baby move). The majority also participated in prenatal activities that supported their partner during the pregnancy (i.e., discuss the pregnancy with child’s mother, buy things for the baby during pregnancy) with the exception of attending birthing classes. Almost all fathers (98% of Mexican American (n = 733) and 99% (n = 299) of other Latinos) saw their newborn in the hospital. Across these two types of prenatal involvement, the only difference between the groups of Latinos was that Mexican American fathers were less likely to report that they saw the baby’s sonogram and discussed the pregnancy with child’s mother (χ2 = 4.38 and 14.28, ps < .05) than other Latino fathers, 89% (n = 683) and 75% (n = 574) versus 93% (n = 285) and 86% (n = 256), respectively).

Mothers of Mexican American infants had lower interaction scores on the NCAST (M = 32.92, SD = 4.39) than did mothers of other-Latino infants (M = 34.77, SD = 4.23; F (1, 905) = 32.61, p < .001). A notable finding is that differences in mother-infant interaction between Mexican American and other Latino parents disappeared when we controlled for sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. education, income) and English proficiency. Mexican American fathers were less warm toward their infants than other-Latino fathers [F (1, 1040) = 4.09, p < .05]. Overall, both ethnic groups of fathers were moderately engaged with their 9-month-old infants in caregiving and physical play but less engaged in literacy activities.

Multivariate Analyses

Bivariate correlations among Mexican American couples’ wantedness, mother-infant interaction and father engagement are presented in the Appendix. Correlations revealed significant associations, although coefficients were small, between fathers’ but not mothers’ desire to have a baby and parenting behaviors. Fathers who wanted the pregnancy were also less engaged in caregiving activities (r = −.08, p < .05). Couples’ agreement about wanting the pregnancy was also associated with less paternal caregiving (r = −.10, p < .05). Furthermore, couple agreement was positively linked to partner relationship quality as reported by mothers (r = .22, p < .001) and fathers (r = .09, p < .05). Whereas mother-reported couple happiness was not significantly associated with mother-infant interaction or paternal engagement, father-reported happiness was positively associated with engagement in literacy activities (r = .08, p < .05), caregiving (r = .12, p < .001), and warmth (r = .10, p < .01).

Appendix.

Correlations among Mexican American Couples’ Wantedness, Mother-Infant Interaction and Father Engagement

| Wantedness | Partner Relationship Quality | Mother-Infant | Father Engagement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mom Wants | Dad Wants | Couple Agreement |

Mom Happy | Dad Happy | Interaction | Literacy | Caregiving | Warmth | |

| Wantedness | |||||||||

| Mom Wants | - | .06 | .55*** | .20*** | .05 | .02 | .07 | −.08 | .02 |

| Dad Wants | .13** | −.01 | .02 | .02 | −.02 | −.08* | .04 | ||

| Couple Agreement | .22*** | .09* | −.02 | −.06 | −.10* | .03 | |||

| Partner Relationship | |||||||||

| Quality | |||||||||

| Mom Happy | .38*** | −.04 | .00 | .01 | .03 | ||||

| Dad Happy | −.01 | .08* | .12*** | .10** | |||||

| Mother-Infant Interactions | |||||||||

| NCATS Parent Score | .15*** | .09* | .09* | ||||||

| Father Engagement | |||||||||

| Literacy (z score) | .33*** | .10** | |||||||

| Caregiving (z score) | .31*** | ||||||||

| Warmth (z score) | - | ||||||||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Table 3 shows the effects of control and explanatory variables on mother-infant interaction and self-reported father engagement (literacy, caregiving, and warmth). Model 1 shows that when mothers reported being happy with their partners, fathers engaged in significantly fewer literacy activities (β = −.24, p < .05) and marginally less caregiving (β = −.17, p < .10). On the other hand, when fathers reported being happy with their partners, they reported more frequent engagement in literacy activities (β = .36, p < .001) and caregiving (β = .22, p < .05). Relationship quality did not have an effect on mother-infant interactions nor on fathers’ expressions of warmth toward their infants.

Table 3.

Mexican American Couples’ Wantedness and Its Interaction with Relationship Quality as Predictors of Mother-Infant Interaction and Father Engagement (n = 735)

| M-I Interaction | Father Engagement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy | Caregiving | Warmth | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Variables | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β |

| Step 1 | Δ R2 = .19* | Δ R2 = .13 | Δ R2 = .20* | Δ R2 = .10 | ||||

| Infant Gender | .03 | .05 | .04 | .00 | .07 | .06 | .02 | −.02 |

| Infant Age | .11 | .12 | −.07 | −.06 | −.06 | −.06 | −.04 | −.04 |

| HH Income | .15 | .14 | −.05 | −.06 | −.14 | −.15 | −.04 | −.02 |

| Mother Education (HS) | −.04 | −.04 | −.06 | −.07 | .05 | .05 | .17 | .18 |

| Mother Education (HS+) | −.07 | −.07 | −.13 | −.14 | −.08 | −.10 | .09 | .05 |

| Father Education (HS) | −.03 | −.04 | −.07 | −.04 | −.08 | −.06 | −.15 | −.13 |

| Father Education (HS+) | .10 | .09 | −.05 | −.07 | −.15 | −.14 | −.06 | −.02 |

| Mother Hours Employed | −.17† | −.18† | −.13 | −.10 | .23** | .24** | .14 | .12 |

| Father Hours Employed | −.08 | −.06 | −.20* | −.21* | −.05 | −.03 | .05 | .06 |

| Mother Age | .06 | .06 | −.05 | −.08 | .20 | .18 | −.02 | −.05 |

| Father Age | .01 | −.01 | .09 | .13 | .00 | .04 | .10 | .18 |

| Mother English Proficiency | .25* | .25* | .22† | .24* | −.21† | −.21† | −.06 | −.04 |

| Father English Proficiency | .05 | .07 | −.12 | −.13 | .27* | .28* | .24† | .21 |

| # Children HH | .10 | .11 | −.01 | −.01 | −.09 | −.10 | −.07 | −.11 |

| Married | .03 | .04 | .15 | .05 | −.25** | −.31*** | −.06 | −.09 |

| Step 2 | Δ R2 = .00 | Δ R2 = .09*** | Δ R2 = .04* | Δ R2 = .01 | ||||

| Mom Happiness | −.07 | −.10 | −.24* | −.27** | −.17† | −.20* | −.11 | −.08 |

| Dad Happiness | .01 | .00 | .36*** | .40*** | .22* | .24** | .06 | .10 |

| Step 3 | Δ R2 = .01 | Δ R2 = .05† | Δ R2 = .03 | Δ R2 = .05† | ||||

| Mom Wanted Pregnancy | −.06 | .30** | .22* | .12 | ||||

| Dad Wanted Pregnancy | −.04 | .06 | −.02 | .01 | ||||

| Mom and Dad Disagreement | .13 | .22* | .15 | .29* | ||||

| Total R2 | .20 | .27 | .27 | .15 | ||||

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Model 2 shows that when mothers wanted the pregnancy, fathers reported engaging in more literacy activities (β = .30, p < .01) and caregiving (β = .22, p < .05) more often than when mothers did not want the pregnancy. On the other hand, when fathers wanted the pregnancy, their level of involvement across the three types of engagement activities was comparable to that of fathers who did not want the pregnancy. Similarly, there were no effects of mothers or fathers wanting the pregnancy on mother-infant interaction scores. However, when couples disagreed (both either wanted the pregnancy or did not want the pregnancy), mothers’ interaction with their infants was unchanged but fathers reported more engagement in literacy activities (β = −.22, p < .05) and warmth activities (β = −.29, p < .05) than when couples agreed. A closer look at the group of couples (42%) who disagreed about the pregnancy revealed that the majority of the fathers (78%) in this group wanted the pregnancy (Table 2).

Moderation Analyses

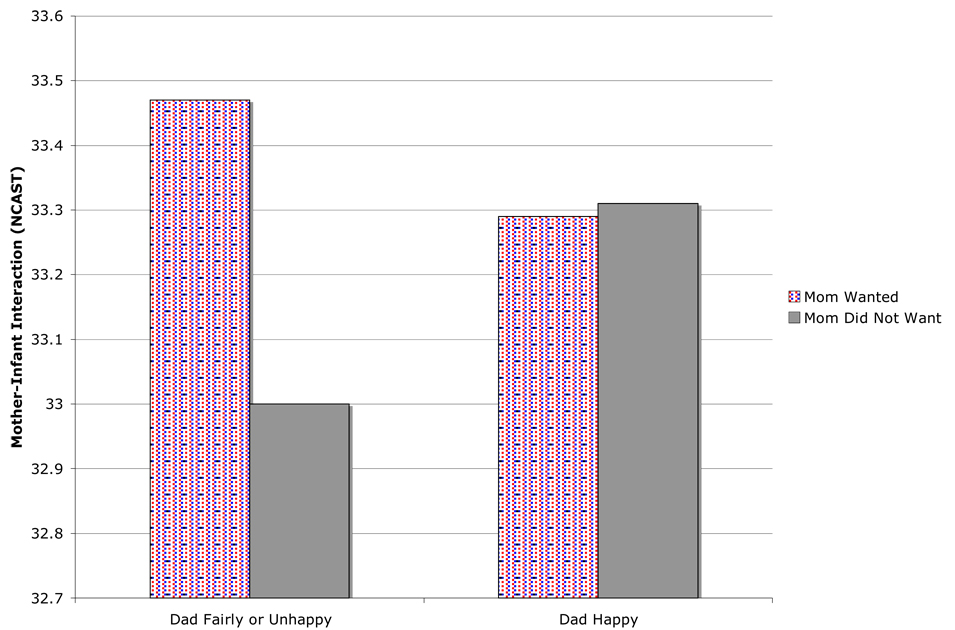

Regression models testing the interaction terms revealed three significant moderation effects (no shown). First, partner relationship quality (father report) significantly moderated the effect of mothers’ wanting the pregnancy on mother-infant interaction quality (β = −.59, p < .05). The plotted means for mother-infant interaction quality shown in Figure 1 suggest that when fathers reported being happy with their partner, mothers interacted with their babies in sensitive ways whether the baby was wanted or not wanted by the mother. However, when fathers were unhappy and the baby was not wanted by the mother, the mother was less sensitive to her infant. This represents a double risk to the child.

Figure 1.

Moderation Effect of Father-Reported Relationship Quality on the Association between Mother Wantedness and Mother-Infant Interactions

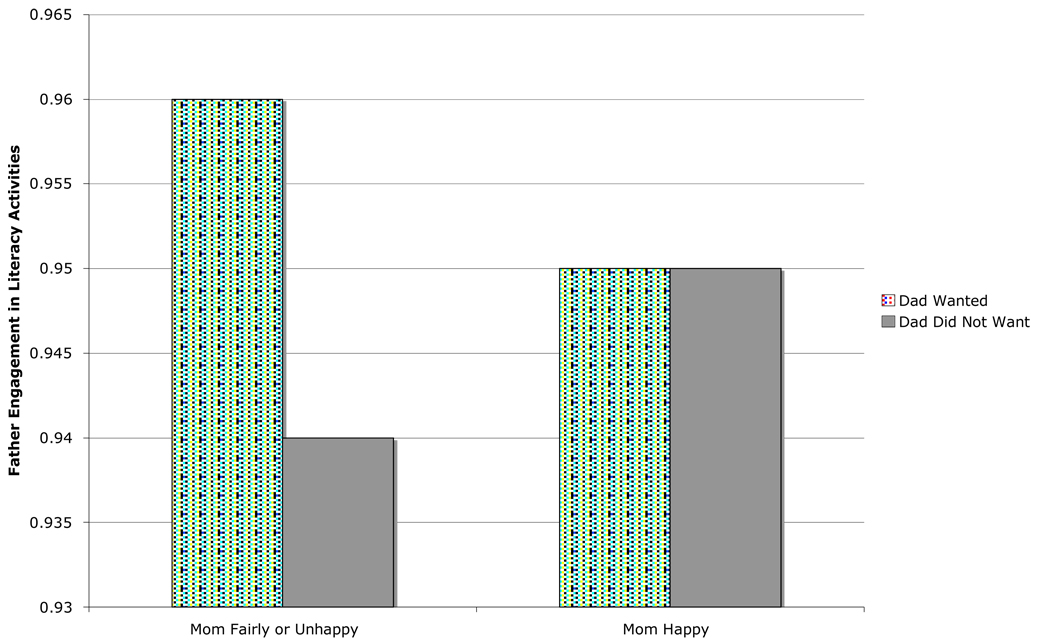

Second, partner relationship quality (mother report) significantly moderated the association between fathers’ wanting the pregnancy and paternal engagement in literacy activities (β = .99, p < .01). Figure 2 shows that when mothers were happy with their partner, fathers engaged in literacy activities whether the baby was wanted or not by the father. When mothers were unhappy and the father did not want the pregnancy, fathers engaged in fewer literacy skills.

Figure 2.

Moderation Effect of Mother-Reported Relationship Quality on the Association between Father Wantedness and Father Engagement in Literacy

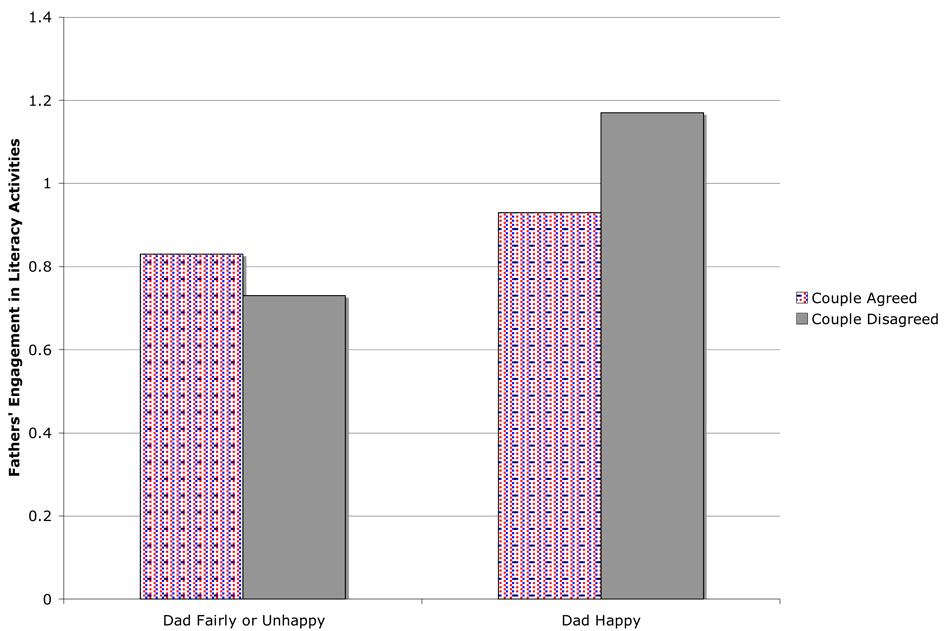

Lastly, partner relationship quality (father report) significantly moderated the effect of couple agreement on paternal engagement in literacy (β = −.62, p < .01). Figure 3 shows that when fathers were happy, disagreement between couples had less effect on father engagement in literacy activities than when fathers were unhappy. When couples disagreed and fathers were unhappy, fathers engaged in fewer literacy skills.

Figure 3.

Moderation Effect of Father-Reported Relationship Quality on the Association between Wantedness Agreement and Father Engagement in Literacy

DISCUSSION

The current study explored associations between mothers’ and fathers’ perceived relationship quality, their desire to have a baby and whether or not they agreed that the pregnancy was wanted with mother-infant interaction and father engagement in a national sample of Mexican-American infants and their resident, biological parents. In contrast to recent population statistics showing that almost half of all U.S. pregnancies are unintended (i.e., unwanted or mistimed as reported by mothers) (Finer & Henshaw, 2006), we found that in our study the majority of Mexican American mothers (58%) and fathers (76%) wanted the pregnancy. Studies of intentionality do not generally distinguish wanting the pregnancy versus intended timing of the pregnancy; if we had included timing data, the percentage of parents who intended the pregnancy might have been higher than we report. We also highlight that the majority of Mexican American mothers in our study report being very happy in their relationship with their partners. These are important strengths suggesting that Mexican American babies are being brought up with parents who are happy and wanted them, underscoring the importance of, and perhaps buffering effect of these strengths on families. Family closeness, in particular partner happiness, may reduce the risk of ineffective parenting. Our findings show that when parents are not happy with one another and the baby is not wanted, mother sensitivity and father involvement decrease, which can place children at risk. Parenting is most effective when parents are happy and the baby is wanted.

Another indication of the importance of the family and the commitment that parents make to their partners and children is the fact that in terms of levels of prenatal involvement, almost all of Mexican American fathers were prenatally involved in ways that connected them to their unborn child (see a sonogram, heard a heart beat) and supported their pregnant partners (buy things for the baby, discussed the pregnancy). Other studies have found moderate levels of prenatal engagement in low-income African American samples and in a national sample of babies and their parents (Cabrera et al., in press; Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007). This finding supports an evolving view of fatherhood among Latinos that is less prescriptive and shows fathers involved with their (Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004).

Next, we explored whether mothers’ and fathers’ desire to have a baby as well as whether agreement about it had any effect on parenting behaviors. Because we wanted to isolate the effect of couples’ shared desire to have a baby on parenting and given that the literature suggests that partner relationship quality is related to parenting, we first examined the effects of relationship quality on parenting behaviors. As predicted from the literature review, we found that relationship quality had significant effects on parenting, but not for both parents and not in the expected direction. Couple happiness (mother or father report) had no effect on mother-infant interaction with their infants or on fathers’ warmth, but it had an effect on reported father engagement in literacy and caregiving activities. The finding for fathers was somewhat counterintuitive. Mothers’ report of couple happiness was significantly linked to less father engagement in literacy and caregiving activities, whereas fathers’ report of couple happiness predicted to more father engagement in these types of activities.

How do we explain these findings? A plausible explanation is that Mexican American fathers, especially those who are happy with their partners, are more willing to let their partners engage in most of the care of their children, especially infants. Because our analyses controlled for levels of acculturation, our findings might reflect deep-held beliefs about who is the best parent to take care of infants. Another possible explanation lies in our measurement of happiness (one global item), which may mask cultural and gender nuances on how mothers and fathers perceive happiness. Perhaps, Mexican American mothers, unlike fathers, do not feel comfortable divulging negative aspects of their private lives to an interviewer or they are merely reporting what is culturally expected of them as married mothers and hence report being happy even when they are not. More research is needed to explore the role of cultural beliefs about parenting roles and how partners perceive the quality of their partner relationship, especially in light of levels of acculturation among low-income Mexican American families.

Our finding that parents’ desire to have a baby had relatively no effect on mother-infant interaction and father s’ engagement with their infants (the only finding was that when mothers wanted the baby, fathers engaged in more literacy and caregiving activities) partially supports predictions from attachment theory, which suggest that parents are more engaged with children who are wanted than with children who are not (Fogany et al., 1991). Our finding also supports previous studies of low-income mothers that found maternal acceptance of the pregnancy was unrelated to maternal warmth (Baydar, 1995; Ispa, et al., 2007) and extends these findings to fathers whose engagement with their children was also unrelated to his intentionality. We also found that father’s engagement in some activities (literacy and caregiving) with their children is influenced by mothers’ desire to have them but not vice versa.

There are several explanations. It is possible that parents’ reports that the baby was wanted (especially when asked retrospectively as it was done in the ECLS-B) is less important than the cultural belief that families and children are valued and need to be loved and cared for. In this sense, family value and loyalty trump personal choice. Although this study does not have a measure of familism (family connection or loyalty), we found that couple happiness, an important component of strong families, is strongly related to father engagement but not to mother-infant interactions, suggesting that at least for mothers their parenting is less dependent on the relationship with their partner. There is evidence that this is the case in non-Latinos samples (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004). Although mothers’ not wanting the baby did not influence fathers’ expression of warmth (tickling) toward their infants, it did influence fathers’ engagement in caregiving (bathing, feeding) and literacy activities (reading, singing songs). A possible explanation is that reading to an infant requires more commitment and motivation from a father than just tickling. However, it is also possible that unwanted pregnancies may have a direct negative effect on child outcomes, but not through parenting, or may emerge later on in the child’s life rather than in infancy. For example, Ispa and her colleagues (2007) found that mothers’ lack of acceptance of pregnancy was negatively related to their children’s attachment security. Similarly, a study of the effects of unwanted childbearing on mother-child relationships found that unwanted pregnancies had long-term negative effect on adolescent’s self-esteem (Barber, Axinn, & Thornton, 1999).

We also explored whether the effect of not wanting a baby on parenting depends on the quality of the partner relationship. We reasoned that a baby who was unwanted at conception might be nevertheless cared for and loved if parents were happy with one another. To explore this possibility, we conducted moderation analyses. We found that when parents are happy, the fact that the baby was unwanted is not a risk factor for insensitive mother-infant interaction. However, mothers who don’t want the baby and have an unhappy relationship with their partner are less sensitive to their children, which puts them a risk for negative outcomes. This is an important finding that offers a window of opportunity to target the quality of the partner relationship in efforts to improve parenting and child outcomes in children who may be at risk.

We were also interested in examining whether the effects of not wanting a child on parenting behaviors are minimized when couples are in agreement about the conception. Parents who either agree to have a baby may experience less conflict and tension in the relationship and therefore be able to parent positively. We found that when couples are happy with one another, disagreement about the pregnancy is not a risk for less father engagement with their children. However, when couples disagreed and are unhappy with each other, fathers are less engaged (in literacy activities) with their children, which can put them at risk. Interestingly, of the couples who disagreed, the majority of the fathers wanted the baby, which explains our direct effect of couple disagreement on increased literacy activities. Thus, fathers are less engaged in literacy activities with their children only when they are unhappy with their partners. This finding also underlies the importance of relationship quality for Mexican American families. Families can be strengthened and supported by addressing the needs of couples as partners; happy couples tend to do more positive parenting than unhappy couples.

It is also noteworthy that the moderation was significant only for one type of father engagement, literacy activities. New conceptualizations of fatherhood have suggested that fathers engage with their children in multifaceted ways (Cabrera et al., 2002; Marsiglio, Lamb, & Day, 2004) and that these different types of activities have different effects on children (Cabrera et al., in press). For example, caregiving activities are basic to children’s survival and consequently tend to be met by most parents and generally less influenced by parents’ and contextual characteristics. In our study, fathers’ engagement in caregiving activities was unrelated to both parent’s intentionality (although it was related to relationship quality). In contrast, engagement in literacy activities (e.g., reading and telling stories) are less fundamental to survival and may also reflect parents’ beliefs about whether or not infants should be read to. However, it is likely that reading and telling stories to an infant is a more intimate and voluntary activity than, for example, bathing There is some evidence that fathers across SES groups engage in fewer literacy activities with their infants than they engage in other type of activities (Cabrera, Hofferth, & Soo, 2007). In our study, fathers engaged in fewer literacy activities than they did in caregiving or warmth-related activities, but engaged in more literacy activities when they reported being happy with their partners. Thus, it appears that for fathers, engagement in more intimate type of activities with their infants may depend on his relationship with his partner.

Several limitations of the present study need to be noted because they suggest next steps in this realm of research. First, our measure of relationship quality is global and may not capture well how couples perceive the quality of their relationship; it may also be an inadequate way to assess relationship quality in a sociocultural context. Second, our study focused on infants, it is possible that links between wantedness and mother-infant interactions emerge later in the child’s life. Third, our study does not include appropriate measures of cultural beliefs and role expectations about fertility decisions. Without these measures, it is difficult to disentangle cultural expectations from personal preferences about fertility in a dynamic context. Fourth, our couple relationship quality measure may not be nuanced enough or culturally sensitive to tap into how couples report on the quality of their relationship.

Even with these caveats, our study makes important contributions. The finding that in a national sample of Mexican American babies, almost 90% are wanted by either parent is an important contribution to the literature on Mexican American families and shows the importance of including both parents’ reports of wantedness of pregnancy. Despite economic hardship, Mexican American babies are being brought up in happy and loving homes, which is very beneficial for children’s development. The majority of Mexican American parents was happy with their partners and displayed positive parenting, even when the babies were not wanted. Disagreement about having the baby or not wanting the baby pose a risk for negative parenting only when parents are unhappy with one each other. Collectively, these findings highlight a number of strengths (relationship quality and father involvement even before the child’s birth) of Mexican American families that can be built upon to offset the negative effects of economic hardship on parenting and children’s development.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by NIH grant (R03 HD049670-01) to the first author. Dr. Shannon was supported by a grant from the American Educational Research Association (“AERA Grants Program”, NSF Grant #REC-0310268 and the PSC-City University of New York Grant Award# 60103-37-38).

Contributor Information

Natasha J. Cabrera, University of Maryland

Jacqueline Shannon, Brooklyn College, CUNY.

Stephanie Mitchell, Children’s Hospital.

Jerry West, Mathematica Policy Resarch, Inc.

References

- Ainsworth MD. Object relations, dependency, and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Development. 1969;40:969–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD. Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. In: Rebelsky F, Dorman L, editors. Child Development and Behavior. 2nd ed. Oxford: Alfred A. Knopf; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach C, Sonenstein F. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, editor. Report of the working group on male fertility and family formation. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nurturing fatherhood: Improving data and research on male fertility, family formation, and fatherhood. 1998

- Barber JS, Axinn W, Thornton A. Unwanted childbearing, health and mother-child relationships. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:231–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N. Consequences for children of their birth planning status. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27:228–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethel J, Green JL, Kalton G, Nord C. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2005. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), Sampling. Volume 2 of the ECLS-B Methodology Report for the 9-Month Data Collection, 2001-02 (NCES 2005-147) [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Dubowitz H, Starr RH. African American fathers in low-income, urban families: Development, behavior, and home environment of their three-year-olds. Child Development. 1999;70:967–978. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Ryan S, Carrano J, Moore K. Father’s prenatal behaviors and attitudes and links to involvement with infants. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2007;69:977–990. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Eisenberg L, editors. The best intentions: Unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Moore K, West J, Boller K, Tamis-LeMonda C. Bridging research and policy: Including fathers of young children in national studies. In: Tamis-Lamonda C, Cabrera N, editors. Handbook of Father Involvement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 489–524. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Fagan J, Farrie D. Explaining the long reach of fathers’ prenatal involvement on later paternal engagement with children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00551.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Fitzgerald HE, Bradley RH, Roggman L. Modeling the Dynamics of Paternal Influences on Children over the Life Course. Journal of Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Garcia Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of father in child development. 4th ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 417–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Hofferth N, Eun Chae S. Determinants of father engagement: Variation by fathers’ ethnicity. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Conference; Montreal Canada. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Shannon JD, West J, Brooks-Gunn J. Parental interactions with Latino infants: Variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Development. 2006;74:1190–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan, England P. Union formation and dissolution in Fragile Families. Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America; March 29–31, 2001; Washington, D.C.. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Rodriguez MD. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns A, Neal-Bernett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 2001. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Gonzales G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings ME, Goeke-Morey MC, Raymond J. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2004. pp. 196–221. [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Goldberg WA. Toddler development in the family: Impact of father involvement and parenting characteristics. Child Development. 1984;55:740–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Bernd E, Whiteman V. Adolescent fathers’ parenting stress, social support, and involvement with infants. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. 2004

- Finer L, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspective Sex Reproductive Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Steele HJ, Steele M. Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment one-year of age. Child Development. 1991;62:891–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa D, Gonzalez N, Barrera M, Dumka L. Interparental relations, maternal employment, and fathering in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;69:26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fox RA, Solis-Camara P. Parenting of young children by fathers in Mexico and the United States. Journal of Social Psychology. 1997;137:489–495. doi: 10.1080/00224549709595465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CC, Duggan AK, Andrews JS, Serwint JR. The father's role during infancy: Factors that influence maternal expectations. Archives Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151:705–711. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170440067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL. Race/ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context or economy? Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsa J, Sable M, Porteer N, Csizmadia A. Pregnancy acceptance, parenting stress, and toddler attachment in low-income Black families. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2007;69:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Smith TS, Green AP, Berndt AE, Rogers MC. Importance of fathers’ parenting to African-American toddler’s social and cognitive development. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:733–744. [Google Scholar]

- Koreman S, Kaestner R, Joyce T. Consequences for infants of parental disagreemtn in pregnancy intention. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34:198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Pleck J, Charnov E. A biosocial perspective on paternal behavior and involvement. In: Lancaster J, Altmann J, editors. Parenting across the life span: Biosocial dimensions. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1987. pp. 111–142. [Google Scholar]

- Leathers SJ, Kelley M. Unintended pregnancy and depressive symptoms among first-time mothers and fathers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:523–531. doi: 10.1037/h0087671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP. Individual and couple intentions for more children: A research note. Demography. 1985;22(1):125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2005. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort: 9-month Public-Use Data File User’s Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, et al. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American Families. Child Development. 2004;75:1613–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R. Fathers’ birth attendance, early contact, and extended contact with their newborns: A critical review. Child Development. 1985;56:392–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Mehta M, Posner S, Poindexter A. Paternal influences on the timing of prenatal care among Hispanics. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2005;9:159–163. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-3012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Rochaat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Gilbert BC, Curtis K, Cabral R, Hirsh J, Schieve L Unintended Pregnancy Workin Group. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:94–101. doi: 10.1363/3509403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JD, Cabrera N, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Lamb ME. Determinants of father involvement: Presence/absence and quality of engagement; Presented at the biennial Society of Research and Child Development meetings; Tampa Bay, FL. 2003. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Camara P, Fox RA. Parenting among mothers with young children in Mexico and the United States. Journal of Social Psychology. 1995;135:591–599. doi: 10.1080/00224549709595465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner G, Spietz A. NCAST caregiver/parent-child interaction teaching manual. Seattle: University of Washington, School of Nursing, NCAST Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Shannon JD, Cabrera N, Lamb ME. Resident fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Development. 2004;75:1806–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce; The Hispanic population in the United States. Current Population Reports. 2000 March;:20–535.

- Weiss RS. The provisions of social relationships. In: Rubin Z, editor. Doing unto others. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1974. pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zuravin SJ. Unplanned childbearing and family size: Their relationship to child neglect and abuse. Family Planning Perspectives. 1991;23:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]