Abstract

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is an intrinsically tumor-specific virus, which is currently under investigation as a clinical oncolytic agent. Several clinical trials have reported NDV to be a safe and effective agent for cancer therapy; however, there remains a clear need for improvement in therapeutic outcome. The endogenous NDV fusion (F) protein directs membrane fusion, which is required for virus entry and cell–cell fusion. Here, we report a novel NDV vector harboring an L289A mutation within the F gene, which resulted in enhanced fusion and cytotoxicity of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells in vitro, as compared with the rNDV/F3aa control virus. In vivo administration of the recombinant vector, termed rNDV/F3aa(L289A), via hepatic arterial infusion in immune-competent Buffalo rats bearing multifocal, orthotopic liver tumors resulted in tumor-specific syncytia formation and necrosis, with no evidence of toxicity to the neighboring hepatic parenchyma. Furthermore, the improved oncolysis conferred by the L289A mutation translated to significantly prolonged survival compared with control NDV. Taken together, rNDV/F(L289A) represents a safe, yet more effective vector than wild-type NDV for the treatment of HCC, making it an ideal candidate for clinical application in HCC patients.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a major worldwide health concern, ranking among the top five most prevalent malignancies.1 The incidence of HCC has more than doubled over the past two decades,2,3 and epidemiological trends suggest that the rate of HCC diagnoses will continue to rise, presumably as a consequence of an ever-increasing prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection and increased alcohol consumption in most industrialized countries.4,5 However, despite incremental advances in treatment, the outcome for HCC patients has not changed significantly. Although surgical resection and liver transplantation are considered to be curative, the majority of HCC cases are detected at an advanced stage, at which time the treatment options are extremely limited.6,7

Oncolytic viruses, which inherently replicate selectively within tumor cells, provide an attractive new tool for cancer therapy. A number of RNA viruses, including reovirus, Newcastle disease virus (NDV), measles virus, and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), are members of this novel class of viruses currently being exploited as potential oncolytic agents.8,9,10 NDV is a nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA virus of the Paramyxoviridae family, whose natural host range is limited to avian species; however, it is known to enter cells by binding to sialic acid residues present on a wide range of human and rodent cancer cells.11 NDV has been shown to selectively replicate in and destroy tumor cells, while sparing normal cells, a property believed to stem from the defective antiviral responses in tumor cells.12,13 Normal cells, which are competent in launching an efficient antiviral response quickly after infection, are able to inhibit viral replication before cell damage can be initiated. The sensitivity of NDV to interferon (IFN), coupled with the defective IFN signaling pathways in tumor cells, provides a mechanism whereby NDV can replicate exclusively within neoplastic tissue.14

Due to compelling preclinical data implicating NDV as an ideal candidate for cancer therapy, phase I and II clinical trials have been initiated.15,16,17 Several have successfully demonstrated that NDV is a safe and effective therapeutic agent, with no reports of pathologic effects in patients beyond conjunctivitis or mild flu-like symptoms.18 Although the results of ongoing clinical trials are encouraging, strategies for improving the therapeutic potential of this virus are warranted, and the established system for generating modified NDV vectors through reverse-genetics has provided a unique opportunity to achieve this aim. To this end, recent reports have demonstrated the successful use of recombinant NDV vectors engineered to express various transgenes to provide improved oncolytic efficacy.19,20

As NDV is an enveloped virus, it initiates infection through attachment to susceptible cells and subsequent membrane fusion, processes directed by two genomic glycoproteins: the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) attachment protein and the fusion (F) protein.21 A recombinant NDV from the strain Hitchner B1 (NDV/B1), expressing a modified F protein with a multibasic cleavage and activation site (rNDV/F3aa), is reported to be highly fusogenic and efficient in tumor-cell killing through formation of large multinucleated cells called syncytia.19,22 Though impressive, it has further been demonstrated that a single amino acid substitution from alanine to leucine at amino acid 289 (L289A) in the F protein, results in even greater syncytial formation.23 In addition to providing the ability to promote fusion in the absence of the viral HN protein, the L289A-modified F protein demonstrates 50–70% augmented fusogenicity in HN-dependent fusion over wild-type F protein.24 We have previously demonstrated that a recombinant VSV vector expressing the NDV/F(L289A) protein successfully promotes syncytial formation, both in vitro and in vivo, and results in enhanced intratumoral viral spread and oncolysis;25,26 however, to date, a recombinant NDV vector harboring the F(L289A) mutation has not been reported.

We hypothesized that we could enhance the promising oncolytic potential of rNDV/F3aa by engineering the F3aa protein to further maximize it fusogenic abilities. Here, we report the cloning and rescue of the modified vector, rNDV/F3aa(L289A). We demonstrate in vitro the superior ability of the F3aa(L289A)-modified virus to promote cell–cell fusion in human and rat HCC cell lines. We then applied the new vector in vivo in a preclinical rat model for HCC, by intrahepatic arterial administration in immune-competent rats bearing multifocal HCC nodules in their livers. We report tumor-specific syncytia formation, in the absence of local or systemic toxicity, which translated to a significant prolongation of survival over buffer- and F3aa control virus-treated rats. These results indicate that rNDV/F3aa(L289A) represents an enhanced oncolytic virus, which could potentially be applied for clinical application for HCC in patients.

Results

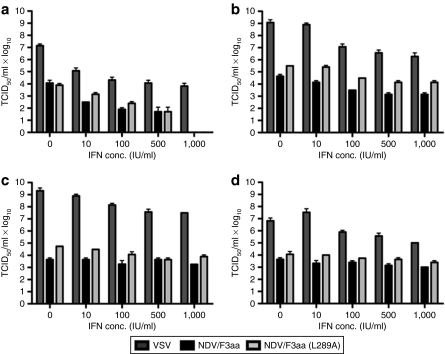

L289A modification does not interfere with the sensitivity of NDV to type I IFN

To determine whether the L289A modification to the fusion protein would alter the relative sensitivity of NDV/F3aa to the inhibitory effects of type I IFN, viral titers of the F3aa and F3aa(L289A) vectors were measured after pretreatment with escalating doses of universal type I IFN and compared with those of rVSV. VSV was chosen as a control for comparison purposes, due to its well-characterized sensitivity to IFN. In primary human hepatocytes (PHHs), both rVSV and the rNDV vectors demonstrated severe growth inhibition in the presence of IFN, even at the lowest dose (10 IU). Although rVSV replication was reduced by 3 logs in the presence of 1,000 IU of IFN, rNDV/F3aa and rNDV/F3aa(L289A) titers dropped 4 logs to a level below detection, and their growth patterns in the presence of each dose of IFN were nearly identical (Figure 1). As predicted, the inhibitory effects of IFN on viral growth were almost negligible in HCC cells, which are known to harbor defects in their IFN signaling pathways.

Figure 1.

rNDV/F3aa(L289A) is sensitive to the inhibitory effects of interferon (IFN). (a) Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs), two human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines [(b) Huh7 and (c) HepG2], and (d) a rat HCC cell line (McA-RH7777) were untreated or treated overnight with increasing concentrations of universal type I interferon (IFN) (10–1,000 IU/ml) in 24-well dishes. Triplicate wells were infected with rVSV-LacZ, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Viral titers were determined by TCID50 of conditioned media harvested 24 hours postinfection. Values represent the mean ± SD. NDV, Newcastle disease virus; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

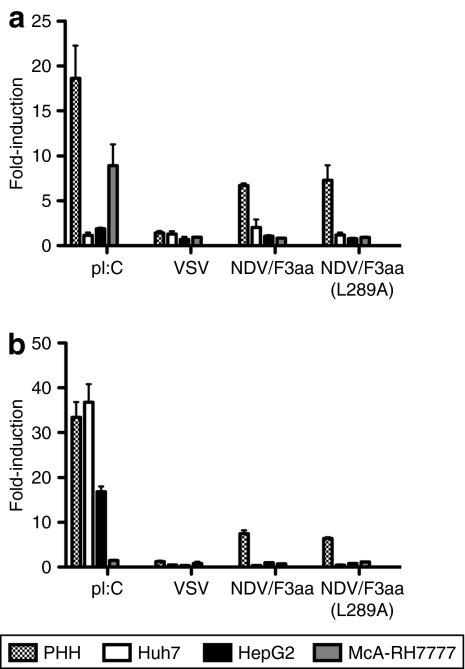

rNDV/F3aa(L289A) effectively induces IFN signaling in PHHs

To determine the ability of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) to induce IFN signaling, PHHs, as well as human and rat HCC cells, were subjected to reporter assays in which the firefly-luciferase reporter was driven by either the IFN-β or the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) promoter. Transfected cells were then stimulated with either rVSV, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) or the positive controls, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid or IFN. Although neither promoter was susceptible to viral stimulation in HCC cells, rNDV proved to be an efficient stimulator of IFN-β and ISRE promoter activity in PHHs (Figure 2). Importantly, the L289A-modified vector behaved similarly to the parental NDV/F3aa vector in its IFN signaling properties. In comparison, rVSV resulted in only minimal promoter induction in PHHs.

Figure 2.

rNDV/F3aa(L289A) induces interferon (IFN) signaling in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs). PHHs, two human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines (Huh7 and HepG2), and a rat HCC cell line (McA-RH7777) were co-transfected with (a) pIFN-β-Luciferase or (b) pISRE-Luciferase and pRL-Luciferase in 24-well dishes. At 24 hours post-transfection, cells were mock-treated, stimulated with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pI:C) (2.5 mg/ml) or IFN (1,000 IU/ml), or infected with rVSV-LacZ, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0 and incubated overnight. Firefly-luciferase activity was normalized to renilla activity to control for transfection efficiency. Fold-induction of the promoters was calculated as a function of luciferase activity in stimulated versus mock-treated cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate measurements. NDV, Newcastle disease virus; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

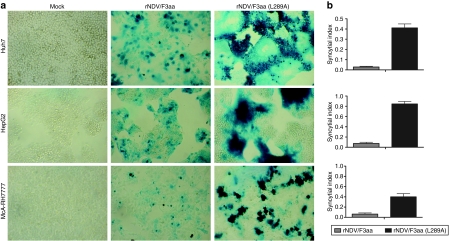

Modified F protein results in enhanced fusion of HCC cells in vitro

To determine whether the L289A mutation in the endogenous NDV/F3aa protein results in enhanced cell–cell fusion, we evaluated the recombinant virus in vitro. Human and rat HCC cells were infected with either rNDV/F3aa or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) and stained for β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression to compare the fusogenicity of each virus. Although moderate β-gal expression and some evidence of fusion could be observed in cells infected with rNDV/F3aa, rNDV/F3aa(L289A) resulted in large syncytial formation, which seemed to originate from infection of a single cell and spread outward as infected cells fused with neighboring cells (Figure 3a). To quantify the hyperfusogenic potential of the modified virus, we counted the number of nuclei per syncytia, and expressed the value in terms of its syncytial index. In all HCC cell lines tested, the syncytial index of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) was significantly higher than that of rNDV/F3aa (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

F(L289A) modification results in enhanced fusogenic activity of Newcastle disease virus (NDV). Human (Huh7 and HepG2) and rat (McA-RH7777) cells were mock infected or infected with rNDV/F3aa or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. At 48 hours postinfection, cells (a) were stained for β-gal expression or (b) analyzed for syncytial index. The syncytial index was calculated as the number of nuclei per syncytia divided by the number of nuclei per field of view. Each cell line was analyzed in triplicate, and data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Hyperfusogenicity does not affect virulence of NDV in chicken embryos

NDV can be classified as highly virulent (velogenic), intermediate (mesogenic), or nonvirulent (lentogenic) based on its pathogenicity in chickens. Because modified F proteins with enhanced fusogenic features are considered to be virulence factors, it was important to determine whether the L289A mutation affected the pathogenicity classification of the virus. For this purpose, we performed a mean death time (MDT) assay in embryonated chicken eggs. Lentogenic strains, which cause asymptomatic infection in birds, are characterized by MDTs of >90 hours; mesogenic strains, causing respiratory disease in birds, have MDTs between 60 and 90 hours; and velogenic strains, which cause severe disease in birds, have MDTs <60 hours. The MDTs of rNDV/F3aa and rNDV/F3aa(L289A) were both ~80 hours (81 and 79.2 hours, respectively), indicating that they are both mesogenic strains, and the F(L289A) mutation did not alter the pathogenicity status from that of the parental strain.

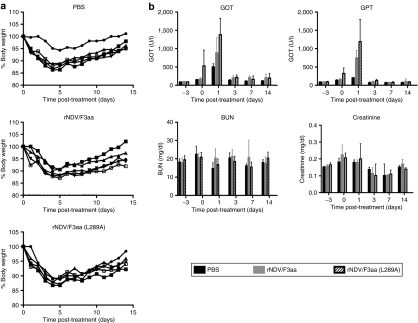

In vivo administration of rNDV results in mild and transient systemic effects

In order to assess potential toxicities associated with high-dose vector administration in vivo, a toxicity study was performed in Buffalo rats. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) was injected by hepatic arterial infusion at a dose of 108 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose), the highest dose achievable due to production limitations. For all animals, minor weight loss and dehydration were observed during the first 4 days following the surgical procedure, but these effects were quickly reversed, and body weights returned to normal by the end of the study (Figure 4a). Serum chemistries revealed insignificant changes in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, and transient elevation of the liver enzymes, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and glutamic pyruvic transaminase, on day 1 after surgery; however, liver enzyme levels returned to normal by day 3 (Figure 4b). Taken together, we concluded that the local and systemic effects of rNDV treatment at 108 TCID50/rat were similar to those resulting from PBS treatment by the same route, and therefore, this represented a safe dose.

Figure 4.

NDV causes transient body weight loss and elevation of liver enzymes in rats. Male non-tumor-bearing Buffalo rats were treated with PBS, or 108 TCID50 of rNDV/F3aa or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) by hepatic arterial infusion (N = 5). (a) Body weight was recorded daily, and (b) blood was drawn at the indicated time points for measurement of serum chemistries (right panel). Values are expressed as mean ± SD. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamic pyruvic transaminase; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose.

Hyperfusogenic NDV induces significant tumor necrosis in HCC tumors in rats

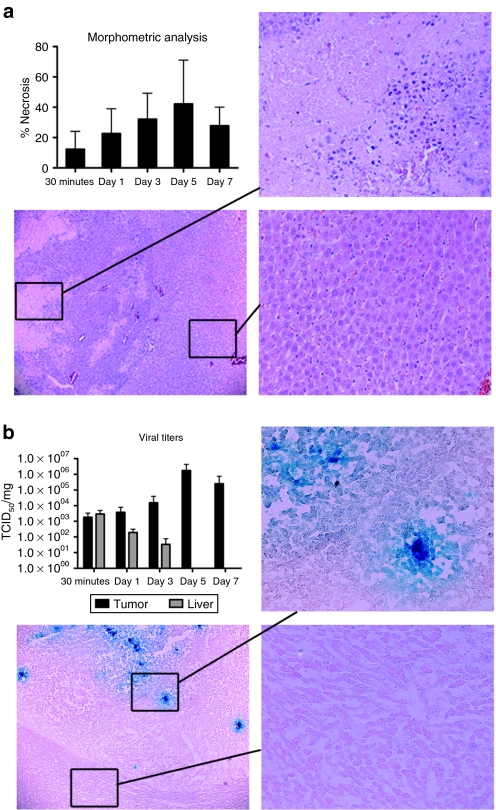

To determine the oncolytic potential and tumor specificity of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) in vivo, rats bearing multifocal HCC tumors in their livers were infused with 108 TCID50 via the hepatic artery. Animals were killed at various time points post-treatment for evaluation of tumor response to therapy. Morphometric analysis of necrotic areas revealed an increase in tumor necrosis, which peaked on day 5 after treatment (Figure 5). Syncytia, which are represented by giant multinucleated cells, were observed within necrotic areas and appeared exclusively in tumor tissue. Histological examination of the surrounding liver parenchyma revealed no signs of hepatotoxicity, and, in particular, there was no evidence of inflammatory cell infiltrates or syncytia formation.

Figure 5.

NDV/F3aa(L289A) treatment results in tumor-specific necrosis and virus replication in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)–bearing rats. Male Buffalo rats bearing multifocal orthotopic HCC nodules were treated with rNDV/F3aa(L289A) (108 TCID50) by hepatic arterial infusion, and killed at the indicated time points post-treatment (n = 3). (a) Tumor-containing liver sections were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining and analyzed for tumor necrosis and liver toxicity. Representative sections are shown at ×5 (overview) and ×20 (magnification of tumor and liver sections) magnification. Morphometric analysis of tumor necrosis was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and is shown as the mean ± standard deviation at each time point. (b) Tumor-containing liver sections were subjected to β-gal staining. Representative sections are shown at ×5 (overview) and ×20 (magnification of tumor and liver sections) magnification. Viral titers were quantified by TCID50 analysis of liver and tumor lysate, and are expressed as the mean ± SD. NDV, Newcastle disease virus; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose.

Hyperfusogenic NDV replicates specifically within HCC tumors in rats

To quantify the in vivo replication kinetics of rNDV replication in HCC and normal liver cells, multifocal HCC-bearing rats were infused with rNDV/F3aa(L289A) through the hepatic artery, and animals were killed at various time points (30 min, 1, 3, 5, and 7 days post-treatment). Sections of liver and tumor were prepared for TCID50 quantitation of viral contents. Although NDV titers steadily increased within tumor tissue, with a peak in replication on day 5, the virus was rapidly cleared from the surrounding liver parenchyma to levels below detection by day 5 (Figure 5b). Similarly, β-gal staining of liver and tumor sections revealed multiple foci of LacZ-postive cells within tumors, whereas no positive staining was observed in the surrounding liver.

Transarterial infusion of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) results in immune cell accumulation in HCC tumors

To determine the immune cell response to NDV therapy of HCC, tumor and liver sections from multifocal tumor-bearing rats were treated with rNDV/F3aa(L289A), and killed at various time points post-treatment. Tumor-containing liver sections were prepared for immunohistochemical staining of various immune cell types. Sections were stained for natural killer (NK) cells with anti-ANK61, neutrophils by antimyeloperoxidase, pan-T cells by anti-OX-52, and macrophages by anti-ED1. Although no significant changes in pan-T cell and macrophage infiltration was observed (data not shown), quantification of marker-positive cells using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) revealed a significant accumulation of NK (P < 0.0001) and myeloperoxidase positive cells (P = 0.04), which peaked on days 5 and 7, respectively, post-treatment (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Infiltration of natural killer (NK) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) cells to NDV/F3aa(L289A) infected hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumors. Rats bearing multifocal HCC lesions were treated by transarterial infusion of NDV/F3aa(L289A) and killed at 30 minutes, and day 1, 3, 5, and 7 after treatment. Tumor-containing liver sections were processed for immunohistochemical staining for (a) NK cell marker and (b) MPO. Positive stained cells were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH), and the mean ± SD are shown. Representative immunohistochemical sections are presented in (c) ×5 and (d) ×20 magnification. NDV, Newcastle disease virus.

Hyperfusogenic NDV results in a survival prolongation in multifocal HCC-bearing rats

Although the short-term effects of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) indicated an oncolytic effect in our HCC model, it remained to be seen whether or not this would translate to a prolongation in survival. To answer this question, rats harboring multifocal HCC lesions in their livers were randomly assigned to be treated with PBS, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) by hepatic arterial infusion (Figure 7). PBS-treated rats began to succumb to tumor progression at 22 days after treatment, and all had expired by day 37 (median survival: 32 days). In contrast, animals treated with rNDV/F3aa survived for up to 57 days, with a median survival of 36.5 days, which was a significant prolongation over PBS treatment (P = 0.0135). However, rNDV/F3aa(L289A) treatment further extended the median survival time to 44 days, which represents a 20% prolongation compared with rNDV/F3aa treatment. Therein, superior oncolytic effects of the hyperfusogenic virus compared to the parental rNDV/F3aa vector translated into a significant survival advantage for rats bearing HCC (P = 0.0377). Furthermore, two animals from the rNDV/F3aa(L289A) treatment group enjoyed long-term tumor-free survival. These rats were killed on day 150 for examination of liver pathology. Macroscopically, there was no visible indication of tumor within the liver or elsewhere, and no histological evidence of residual tumor cells or liver abnormality was observed. These results indicate that even large multifocal lesions (up to 10 mm in diameter at the time of treatment) had undergone complete remission in these animals, which translated into long-term and tumor-free survival.

Figure 7.

rNDV/F3aa(L289A) therapy results in significant survival prolongation hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)–bearing rats. Male Buffalo rats bearing multifocal HCC lesions were treated by hepatic arterial infusion of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (n = 10), rNDV/F3aa (n = 14), or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) (n = 13) and followed for survival. Animals were monitored daily, and survival was plotted as a Kaplan–Meier survival curve. P values for PBS versus rNDV/F3aa is <0.02, for rNDV/F3aa versus rNDV/F3aa(L289A) is <0.04. Statistical significance was determined by log-rank test. NDV, Newcastle disease virus.

Discussion

Our previous work has focused on the characterization and development of VSV vectors for the treatment of HCC in an orthotopic, immune-competent rat model. Although these studies produced encouraging results, we were intrigued by the possibility of establishing a second oncolytic virus system in our model. NDV represented an attractive vector because naturally occurring strains have been applied for clinical application as oncolytic agents for several decades, and the outcomes of phase I and II clinical trials have been positive. Despite this fact, further development of NDV vectors is necessary for optimal antitumor efficacy, affording us the opportunity to define the oncolytic potential of NDV in our model, while simultaneously enhancing it.

It has previously been demonstrated that the construction of a recombinant NDV vector based on the attenuated (lentogenic) Hitchner B1 strain, with a modified F protein (rNDV/F3aa), resulted in syncytia formation in tumor cells and an improved therapeutic response compared to that of rNDV/B1 in immunocompetent tumor-bearing mice.19 The F protein is formed from a precursor, F0, which is not capable of fusogenic activity before cleavage into functional disulfide-linked F1 and F2 polypeptides. The F protein cleavage sequences are recognized by distinct cellular proteases, and the F0 proteins from lentogenic viruses can only be cleaved by trypsin-like proteases found in the respiratory and intestinal tracts of birds.27 In contrast, the F3aa modification of the cleavage site into a polybasic amino acid sequence allows the protein to be cleaved by intracellular proteases, thereby permitting the virus to enter a wide range of cells more effectively and form syncytia in the absence of exogenous proteases.28 Importantly, although the cleavage site of the NDV F protein has been postulated to be a major determinant of virulence,29 the F3aa modification only moderately upgraded the virulence classification from lentogenic to intermediate (mesogenic) in embryonated chicken eggs, based on the MDT assay.30 Because this F3aa-modified vector has already demonstrated antitumor efficacy in several cancer models,19,31 we chose the rNDV/F3aa vector as the basis for additional modifications to further enhance the oncolytic potential.

It has previously been demonstrated that a single amino acid substitution in the F protein (L289A) alters the requirement for NDV HN in the promotion of fusion.23 NDV F carrying this substitution is capable of promoting a significant level of syncytial formation in some cell types in the absence of HN. In addition, when F(L289A) is expressed in the presence of HN protein, syncytial formation is greatly enhanced compared to that observed when the wild-type F is applied.24 We have previously exploited the unique features of the F(L289A) mutation to create a fusogenic rVSV expressing the exogenous NDV/F(L289) gene. We demonstrated that this novel vector was competent in forming syncytia in tumor cells in vitro and enhanced the spread and oncolysis of VSV in an immune-competent rat model of HCC, while maintaining its tumor specificity and introducing no indication of additional toxicity.25 Although the superior fusogenic features of NDV/F(L289A) had been well characterized through the use of expression vectors and an exogenous virus (VSV), to date there have been no published reports of an rNDV vector engineered to encode the L289A mutation in its endogenous F protein.

We hypothesized that the incorporation of the L289A mutation into the rNDV/F3aa vector would result in an enhanced oncolytic agent, which could spread easily throughout the tumor mass via cell–cell fusion and result in significant tumor necrosis and survival prolongation in an animal model of cancer. To this end, we cloned and rescued the recombinant vector, rNDV/F3aa(L289A).

The acute sensitivity of NDV to the antiviral effects of IFN has been proposed as the potential mechanism underlying the tumor selectivity of NDV replication,32 as multiple defects in IFN signaling are known to be manifest in malignant transformation.33 In particular, primary HCC and HCC cell lines are known to harbor defects in their IFN induction33 and response pathways.34 Therefore, it was critical to rule out the possibility that the L289A modification could inadvertently alter IFN signaling in infected cells or inhibit the intrinsic sensitivity of NDV to IFN-mediated protection of nontumor cells. Indeed, pretreatment of PHH resulted in a striking reduction in NDV/F3aa(L289A) titers. These results were comparable to those observed with NDV/F3aa and VSV, whose marked sensitivity to IFN has been extensively characterized by us and others.10,34 Using luciferase reporter genes driven by the IFN-β and ISRE promoters, we similarly demonstrated that NDV/F3aa(L289A) is a competent stimulator of IFN induction and response, respectively, in PHH, while causing no appreciable induction in HCC cells. In contrast, VSV resulted in a quite modest induction of IFN signaling, indicating that NDV could potentially possess a more powerful mechanism for tumor specificity, thereby providing a benefit over VSV as the optimal oncolytic agent.

Based on in vitro characterization of syncytial formation, which demonstrated a striking enhancement of fusion promoted by the F(L289A)-modified vector compared to the wild-type F vector, we were encouraged to compare the two vectors in vivo to determine whether or not these results would translate into a difference in therapeutic outcome. Because we have extensively characterized the effects of oncolytic VSV therapy in our preclinical rat model of HCC, we chose to utilize the same model in our NDV studies to allow an indirect comparison of the two vector systems.

Hepatic arterial infusion of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at the highest obtainable dose yielded no appreciable signs of toxicity, and histological and immunohistochemical analyses revealed syncytial formation, necrosis, and NDV-mediated LacZ expression exclusively within tumors, whereas none could be detected in the surrounding liver. Quantification of infectious NDV particles within liver and tumor tissue demonstrated tumor-specific viral replication, with viral titers falling below the level of detection in normal liver by day 5 post-treatment. Finally, Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis demonstrated a significant survival benefit conferred by rNDV/F3aa(L289A) treatment compared with rNDV/F3aa or PBS. These results are comparable to the survival prolongation we achieved through VSV treatment in this HCC model,25,35 and it will be interesting to compare these two vector systems side by side in future studies.

The establishment of two independent oncolytic viruses providing effective therapy to a single tumor model provides the unique opportunity to administer combination viral therapy for an additive, or potentially synergistic effect through a “prime-boost” approach for induction of a robust antitumor immune response. In addition, neutralizing antiviral antibodies begin circulating several days after viral administration, thereby significantly limiting the efficacy of readministration of the same virus. The potential to administer an adjuvant treatment at a later time point using a heterologous virus would provide a novel strategy to circumvent this obstacle to in vivo viral therapy.

The significant survival benefit of the hyperfusogenic NDV vector may be attributable to several factors. The process of syncytial formation is known to enhance oncolysis through a phenomenon known as the “bystander effect”.36 This effect involves the recruitment of adjacent nontransduced cells into the growing syncytium, thereby amplifying the degree of cell killing exponentially compared to that achieved by nonfusogenic viruses. In this regard, enhancement of the fusogenic capacity of a virus would provide an enormous oncolytic advantage in spread throughout the tumor mass, which is a major obstacle limiting the effectiveness of conventional oncolytic viral therapy in vivo.37,38 Furthermore, cancer cell death through viral-mediated syncytia formation results in tumor necrosis, a process believed to lead to highly efficient immune activation and potentially potent antitumor responses.39 In fact, we observed a statistically significant accumulation of NK cells and neutrophils following local transarterial infusion of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) to HCC. Natural killer cells are a major component of the innate immune system, and act as a first line of defense against invading pathogens and viruses before the launch of the adaptive immune responses.40,41 NK cells represent a distinct population of cytotoxic lymphocytes characterized by the CD16+ and/or CD56+ phenotype, and they mediate direct lysis of target cells by releasing cytotoxic granules containing lytic enzymes, or by binding to apoptosis-inducing receptors on the target cell.42 Furthermore, NK cells play an important role in adaptive antitumor immunity by mediating tumor antigen-specific crosspriming of T cells by plasmacytoid dendritic cells.43 Our observation of NK cell accumulation following NDV infection is in line with published data describing the direct activation of NK cells by NDV-infected tumor cells, and the subsequent induction of the effector lymphokines, γ-IFN and tumor necrosis factor α.44 Therefore, the superior oncolytic effect of hypofusogenic rNDV/F(L289A) may be the combined result of enhanced killing of bystander cell coupled with augmented antitumor immunity.

It is noteworthy to mention the potential safety concerns raised by the concept of uncontrolled viral-mediated syncytia induction. Although modifications to the F protein have been correlated to changes in virulence, a MDT assay in embryonated chicken eggs demonstrated that the F(L289A) mutation did not alter the virulence classification from that of the parental mesogenic Hitchner B1/F3aa strain. Moreover, the F modification did not alter the ability of the virus to elicit an innate IFN response in normal cells, nor did it interfere with the intrinsic IFN sensitivity of NDV, which is important for maintenance of tumor specificity. Indeed, hepatic arterial infusion of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) resulted in tumor-specific syncytia formation and caused no observable damage to surrounding hepatocytes or signs of systemic toxicity.

Despite the significant survival prolongation conferred by the modified F virus, most animals succumbed to relapse, indicating that additional enhancements to the treatment regimen are warranted. We previously demonstrated that VSV therapy for HCC could be significantly improved via repeated hepatic arterial administration of the vector45 and through coadministration with a clinically available embolization agent.46 Therefore, it is anticipated that similar strategies applied to NDV could result in comparable benefits in therapeutic outcome. Furthermore, recent reports have described the efficacy of foreign gene insertion into the NDV genome for enhanced oncolytic response,19,20 and the integration of therapeutic genes into the hyperfusogenic vector could exponentially improve the oncolytic potential of NDV therapy. Although it will be interesting to investigate each of these strategies, as well as to perform more detailed mechanistic studies to elucidate the means by which hyperfusogenic NDV exerts its therapeutic effects, these experiments are beyond the scope of this study. This report focuses on the preclinical characterization of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) as a safe and effective oncolytic agent for the treatment of HCC.

In conclusion, we have investigated the potential to enhance the inherent oncolytic efficacy of NDV by augmenting syncytia formation through a single amino acid substitution in the endogenous F gene. Using an orthotopic preclinical model of HCC, we determined that hepatic arterial delivery of rNDV/F3aa(L289A) results in significantly enhanced efficacy over the previously reported NDV/F3aa vector, while maintaining tumor specificity. Although naturally occurring strains of NDV have been employed in encouraging clinical studies for several decades,47 the development of the reverse-genetics system for creating genetically engineered vectors has opened new doors for the optimization of viral agents. It remains to be seen how these modified vectors will translate into clinical application. Based on the data presented here, the F3aa(L289A)-modified NDV virus represents an attractive new vector for future clinical trials for HCC and, presumably, other types of cancer in the future.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were a kind gift from Ulrich Lauer (University Hospital of Tübingen). The DF1 chicken fibroblast cell line was provided by Roger Vogelmann (Klinikum rechts der Isar, Munich, Germany), and primary chicken embryo fibroblasts were obtained from Ingo Drexler (Klinikum rechts der Isar). A549, McA-RH7777, and BHK-21 cells were purchased from ATCC (Rockville, MD). HepG2, Huh7, and A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine (200 mmol/l), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate. McA-RH7777, DF1, and chicken embryo fibroblast cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. BHK-21 cells were cultured in Glasgow MEM BHK-21 medium (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% tryptose phosphate broth. DF1 cells were maintained in a 39 °C incubator with 5% CO2; all other cell lines were grown at 37 °C under 5% CO2. All cell cultures were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

PHHs were isolated from patients (negative for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus) who underwent surgical resections of liver tumors, in accordance with the guidelines of the charitable state controlled foundation of Human Tissue and Cell Research (Regensburg, Germany).48 PHHs were isolated from the resected nontumorous margin and maintained in culture with HepatoZYME-SFM medium (GIBCO) containing 1% L-glutamine.

Viruses. The NDV complementary DNA sequence was derived from the mesogenic Hitchner B1 strain engineered to express the modified F cleavage site (F3aa), as previously described.30 The LacZ gene was inserted as an additional transcription unit into the unique XbaI restriction site between the P and M genes in the full-length plasmid, pT7NDV/F3aa (a kind gift from Adolfo Garcia-Sastre; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY). To generate the recombinant NDV vector expressing the mutant F3aa(L289A) F protein, the pT7NDV/F3aa plasmid was modified by site-directed PCR mutagenesis. To this end, a long forward primer (5′-GGCTTAATCACCGGTAACCCTATTCTATACGACTCACAGACTCAACTCTTGGGTATACAGGTAACTGCACCTTCAGTCGGGAAC-3′) was designed to span amino acid 289, as well as the upstream AgeI restriction site. The reverse primer (5′-GTCATCTACAACCGGTAGTTTTTTCTTAACTCTCCG-3′) corresponded to the noncoding region between the F and HN genes, including a second AgeI restriction site. The nucleotides substituted in the primers to mutate the amino acid at position 289 from Leu to Ala appear in boldface, while sequences corresponding to the restriction sites are underlined. The resulting PCR fragment was then purified and digested with AgeI, and inserted back into the full-length pT7NDV/F3aa plasmid, thereby replacing the corresponding segment of the endogenous F gene. Sequences of all modified plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eurofins MWG, Ebersberg, Germany). Viruses were rescued using an established method of reverse-genetics.49 For simplicity, the rNDV/F3aa-LacZ and rNDV/F3aa(L289A)-LacZ vectors will be referred to as rNDV/F3aa and rNDV/F3aa(L289A). The rVSV-LacZ control virus was generated as previously described.35

To amplify NDV stocks, 10 day-old embryonated pathogen-free chicken eggs were inoculated with 100 plaque-forming units of virus, and the allantoic fluid was harvested 48 hours later and pooled. The fluid was cleared by centrifugation at 1,800 g for 30 minutes, and then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 24,000 r.p.m. for 24 hours. The pellet was resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution and layered on top of a sucrose gradient ranging from 60 to 10%, and ultracentrifuged for 1 hour at 24,000 r.p.m. The band containing the virus was carefully collected with a syringe and 20 G needle, and ultracentrifuged for another hour at 24,000 r.p.m. to remove the sucrose. The pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution and aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. Titers were determined by TCID50 analysis in DF1 cells.

IFN sensitivity assay. PHH and HCC cell lines (HepG2, Huh7, and McA-RH7777) were seeded in 24-well dishes at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. Monolayers were mock-treated or treated overnight with Universal type I IFN (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ) at concentrations of 10, 100, 500, and 1,000 IU/ml. Following the pretreatment, the cells were infected with either rVSV-LacZ, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at a multiplicity of infection of 1. At 24 hours postinfection, aliquots of the conditioned media were harvested and subjected to TCID50 determination of viral titers.

IFN-β and ISRE promoter induction assays. PHH, Huh7, HepG2, and McA-RH7777 cells were seeded in 24-well dishes at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. Cells were transfected with a firefly-luciferase reporter plasmid driven by either the IFN-β or ISRE promoter, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, to control for transfection efficiency, cells were co-transfected with the Renilla reniformis plasmid. At 24 hours post-transfection, the cells were either mock-treated, or stimulated with poly I:C (2.5 µg), universal type I IFN (500 IU), or rVSV-LacZ, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at an multiplicity of infection of 1. Following overnight incubation, cell lysates were prepared, and the luciferase activities were quantified using the Dual-Luciferase Assay system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) with a standard luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). The relative light units of firefly-luciferase activity were normalized to the constitutively active Renilla luciferase, and presented as the fold-induction of stimulated, compared to mock-treated cells.

Quantitation of syncytium formation. Huh7, HepG2, and McA-RH7777 cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/well in 6-well dishes. Upon attachment, they were infected with rNDV/F3aa or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) at an multiplicity of infection of 0.1 in triplicate. At 48 hours postinfection, the cells were stained using the β-gal staining set (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers instructions. For a quantitative assessment, the nuclei were labeled with propidium iodide and counted. The syncytial index was calculated as the number of nuclei per syncytia divided by the otal number of nuclei per field of view.

MDT assay. The 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs were infected with serial tenfold dilutions of viruses, with five eggs per virus dose. The eggs were incubated at 37 °C and monitored twice daily for 7 days, and the time at which the embryos were found dead was recorded. The highest dilution that killed all embryos was considered to be the minimum lethal dose. The MDT was then calculated as the mean time required for the embryos to be killed at the minimum lethal dose.

Animal studies. All procedures involving animals were approved and performed according to the guidelines of the institution's animal care and use committee, and the government of Bavaria, Germany. Six-week-old male Buffalo rats were purchased from Harlan Winkelmann (Borchen, Germany), and housed under standard conditions.

To assess the potential toxicity of rNDV vectors when administered at 108 TCID50/rat, non-tumor-bearing Buffalo rats were subjected to laparotomy for preparation of the hepatic artery, whereby a 1 ml suspension of PBS, rNDV/F3aa, or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) was slowly infused. Body weights were monitored daily from 0 to 14 days post-treatment. In addition, serum was prepared from whole blood drawn on days −3, 0, 1, 3, 7, and 14 for determination of serum concentrations of glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, glutamic pyruvic transaminase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine. All serum chemistry measurements were performed by the Institute for Clinical Chemistry and Pathobiochemistry (Klinikum rechts der Isar).

To establish multifocal HCC lesions within the liver, 107 syngeneic McA-RH7777 rat HCC cells were infused as a 1 ml suspension in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium through the portal vein. A second laparotomy was performed 21 days after tumor-cell implantation to screen for the development of multifocal hepatic tumors of 1–10 mm in diameter. To determine in vivo oncolysis, as well as the intratumoral kinetics of NDV spread, rats bearing multifocal HCC were treated with 108 TCID50 rNDV/F3aa(L289A) via the hepatic artery. Five animals were randomly chosen for killing at each of the following time points: 30 min, day 1, 3, or 7. Upon killing, sections of liver and tumor were snap frozen for TCID50 determination of intratumoral and intrahepatic viral titers or prepared for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. An additional set of tumor-bearing rats was treated with PBS (n = 10), rNDV/F3aa (n = 13), or rNDV/F3aa(L289A) (n = 14) and followed for survival to compare the therapeutic outcome of each treatment. The animals were monitored daily and killed at humane end points, and data were plotted as a Kaplan–Meier survival curve.

Histology and immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections containing both liver and tumor were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Sections of 3 µm thickness were subjected to hematoxylin–eosin staining for histological analysis, or immunohistochemically stained for myeloperoxidase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or the NK cell marker, ANK61 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Positive cells were detected using the ImPRESS Universal Reagent Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Additional sections were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 4 hours followed by overnight incubation in 18% sucrose. The tissue was then embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and frozen on dry ice. Cryostat sections of 10 µm in thickness were stained using the β-gal Staining Set (Roche) for 16 hours at 37 °C, and counterstained with eosin.

Statistical analyses. For comparison of individual data points, a two-sided Student t-test was applied to determine statistical significance. Survival curves were plotted according to the Kaplan–Meier method, and statistical significance between different treatment groups was determined using the log-rank test. Statistical data were obtained using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Lindner for excellent technical assistance. We express our appreciation to Human Tissue and Cell Research (HTCR, Regensburg) for providing human primary hepatocytes. This work was supported in part by the German Research Aid (Max-Eder Research Program) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant 01GU0505).

REFERENCES

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J., and , Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer Z, Peltekian K., and , van Zanten SV. Review article: the changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Canada. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ., and , McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:817–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuffic S, Poynard T, Buffat L., and , Valleron AJ. Trends in primary liver cancer. Lancet. 1998;351:214–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathurin P, Rixe O, Carbonell N, Bernard B, Cluzel P, Bellin MF, et al. Review article: overview of medical treatments in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma—an impossible meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:111–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Burroughs A., and , Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorence RM, Katubig BB, Reichard KW, Reyes HM, Phuangsab A, Sassetti MD, et al. Complete regression of human fibrosarcoma xenografts after local Newcastle disease virus therapy. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6017–6021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng KW, Ahmann GJ, Pham L, Greipp PR, Cattaneo R., and , Russell SJ. Systemic therapy of myeloma xenografts by an attenuated measles virus. Blood. 2001;98:2002–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl DF, Lichty B, Knowles S, Marius R, Atkins H, Sonenberg N, et al. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat Med. 2000;6:821–825. doi: 10.1038/77558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard KW, Lorence RM, Cascino CJ, Peeples ME, Walter RJ, Fernando MB, et al. Newcastle disease virus selectively kills human tumor cells. J Surg Res. 1992;52:448–453. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(92)90310-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S, Barber GN. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) therapy of tumors. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:135–138. doi: 10.1080/713803696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl DF, Lichty BD, tenOever BR, Paterson JM, Power AT, Knowles S, et al. VSV strains with defects in their ability to shutdown innate immunity are potent systemic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, García-Sastre A, Cros JF, Basler CF., and , Palese P. Newcastle disease virus V protein is a determinant of host range restriction. J Virol. 2003;77:9522–9532. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9522-9532.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotte SJ, Lorence RM, Hirte HW, Polawski SR, Bamat MK, O'Neil JD, et al. An optimized clinical regimen for the oncolytic virus PV701. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:977–985. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AI, Zakay-Rones Z, Gomori JM, Linetsky E, Rasooly L, Greenbaum E, et al. Phase I/II trial of intravenous NDV-HUJ oncolytic virus in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Ther. 2006;13:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csatary LK, Gosztonyi G, Szeberenyi J, Fabian Z, Liszka V, Bodey B, et al. MTH-68/H oncolytic viral treatment in human high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;67:83–93. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000021735.85511.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemunaitis J. Live viruses in cancer treatment. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2002;16:1483–1492; discussion 1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil A, Park MS, Martinez O, Chua MA, Xiao S, Cros JF, et al. Use of reverse genetics to enhance the oncolytic properties of Newcastle disease virus. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8285–8292. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke M, Peeters B, de Leeuw O, Moorman R, Arnold A, Fournier P, et al. Recombinant Newcastle disease virus (NDV) with inserted gene coding for GM-CSF as a new vector for cancer immunogene therapy. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1639–1649. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RA. Paramyxovirus fusion: a hypothesis for changes. Virology. 1993;197:1–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AR, Harrington KJ, Kottke T, Ahmed A, Melcher AA, Gough MJ, et al. Viral fusogenic membrane glycoproteins kill solid tumor cells by nonapoptotic mechanisms that promote cross presentation of tumor antigens by dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6566–6578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergel TA, McGinnes LW., and , Morrison TG. A single amino acid change in the Newcastle disease virus fusion protein alters the requirement for HN protein in fusion. J Virol. 2000;74:5101–5107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5101-5107.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Melanson VR, Mirza AM., and , Iorio RM. Decreased dependence on receptor recognition for the fusion promotion activity of L289A-mutated Newcastle disease virus fusion protein correlates with a monoclonal antibody-detected conformational change. J Virol. 2005;79:1180–1190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1180-1190.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert O, Shinozaki K, Kournioti C, Park MS, García-Sastre A., and , Woo SL. Syncytia induction enhances the oncolytic potential of vesicular stomatitis virus in virotherapy for cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3265–3270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Chang JI, Choi B, Wanna G, Ebert O, Genden EM, et al. Fusogenic vesicular stomatitis virus for the treatment of head and neck squamous carcinomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi T, Matsuda Y, Kiyokage R, Kawahara N, Kiyotani K, Katunuma N, et al. Identification of endoprotease activity in the trans Golgi membranes of rat liver cells that specifically processes in vitro the fusion glycoprotein precursor of virulent Newcastle disease virus. Virology. 1991;184:504–512. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90420-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters BP, de Leeuw OS, Koch G., and , Gielkens AL. Rescue of Newcastle disease virus from cloned cDNA: evidence that cleavability of the fusion protein is a major determinant for virulence. J Virol. 1999;73:5001–5009. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5001-5009.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw OS, Hartog L, Koch G., and , Peeters BP. Effect of fusion protein cleavage site mutations on virulence of Newcastle disease virus: non-virulent cleavage site mutants revert to virulence after one passage in chicken brain. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:475–484. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, Steel J, García-Sastre A, Swayne D., and , Palese P. Engineered viral vaccine constructs with dual specificity: avian influenza and Newcastle disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8203–8208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602566103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarin D, Vigil A, Kelly K, García-Sastre A., and , Fong Y. Genetically engineered Newcastle disease virus for malignant melanoma therapy. Gene Ther. 2009;16:796–804. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy S, Takimoto T, Scroggs RA., and , Portner A. Differentially regulated interferon response determines the outcome of Newcastle disease virus infection in normal and tumor cell lines. J Virol. 2006;80:5145–5155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02618-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskinen P, Nyqvist M, Sareneva T, Pirhonen J, Melén K., and , Julkunen I. Impaired antiviral response in human hepatoma cells. Virology. 1999;263:364–375. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marozin S, Altomonte J, Stadler F, Thasler WE, Schmid RM., and , Ebert O. Inhibition of the IFN-beta response in hepatocellular carcinoma by alternative spliced isoform of IFN regulatory factor-3. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1789–1797. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Ebert O, Kournioti C, Tai YS., and , Woo SL. Oncolysis of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in the rat liver by hepatic artery infusion of vesicular stomatitis virus. Mol Ther. 2004;9:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Bullough F, Murphy S, Emiliusen L, Lavillette D, Cosset FL, et al. Fusogenic membrane glycoproteins as a novel class of genes for the local and immune-mediated control of tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1492–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CO. Overcoming the extracellular matrix barrier to improve intratumoral spread and therapeutic potential of oncolytic virotherapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise CC, Williams A, Olesch J., and , Kirn DH. Efficacy of a replication-competent adenovirus (ONYX-015) following intratumoral injection: intratumoral spread and distribution effects. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:499–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher A, Todryk S, Hardwick N, Ford M, Jacobson M., and , Vile RG. Tumor immunogenicity is determined by the mechanism of cell death via induction of heat shock protein expression. Nat Med. 1998;4:581–587. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh RM. Regulation of virus infections by natural killer cells. A review. Nat Immun Cell Growth Regul. 1986;5:169–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutkiewicz RR., and , Welsh RM. Major histocompatibility complex class I antigens and the control of viral infections by natural killer cells. J Virol. 1995;69:3967–3971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.3967-3971.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS, Fassett MS, Koopman LA, Boyson JE., and , Strominger JL. Viral evasion of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1006–1012. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Lou Y, Lizée G, Qin H, Liu S, Rabinovich B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce NK cell-dependent, tumor antigen-specific T cell cross-priming and tumor regression in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1165–1175. doi: 10.1172/JCI33583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarahian M, Watzl C, Fournier P, Arnold A, Djandji D, Zahedi S, et al. Activation of natural killer cells by Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. J Virol. 2009;83:8108–8121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00211-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Ebert O., and , Woo SL. Eradication of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats via repeated hepatic arterial infusions of recombinant VSV. Hepatology. 2005;41:196–203. doi: 10.1002/hep.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomonte J, Braren R, Schulz S, Marozin S, Rummeny EJ, Schmid RM, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of transarterial viroembolization for multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Hepatology. 2008;48:1864–1873. doi: 10.1002/hep.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel WA., and , Garrett RE. Newcastle disease virus as an Antineoplastic Agent. Cancer. 1965;18:863–868. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196507)18:7<863::aid-cncr2820180714>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thasler WE, Weiss TS, Schillhorn K, Stoll PT, Irrgang B., and , Jauch KW. Charitable State-Controlled Foundation Human Tissue and Cell Research: Ethic and Legal Aspects in the Supply of Surgically Removed Human Tissue For Research in the Academic and Commercial Sector in Germany. Cell Tissue Bank. 2003;4:49–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1026392429112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya T, Cros J, Park MS, Nakaya Y, Zheng H, Sagrera A, et al. Recombinant Newcastle disease virus as a vaccine vector. J Virol. 2001;75:11868–11873. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11868-11873.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]