Abstract

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is an uncommon benign disorder of the breast that can mimic two frequent breast disorders, breast carcinoma and breast abscess. In this report, we present two patients seen in a community teaching hospital over a period of one year, diagnosed with IGM after histological evaluation. One patient responded well to immunosuppressive therapy, but the second patient required bilateral mastectomy due to the severe and recurrent nature of the disease. IGM is a disorder that should be considered in the evaluation of women who present with painful breast disease. We discuss the diagnosis, clinical presentation and management of IGM.

KEY WORDS: idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, mastitis, granulomas

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is an uncommon, non-malignant, chronic inflammatory breast condition that was first described by Kessler and Wolloch in 1972.1 IGM can mimic two very frequent breast disorders, breast carcinoma and breast abscess. Most patients are women of child bearing age with a recent history of pregnancy and lactation.2–4 IGM typically presents as a unilateral breast mass, sometimes with skin or lymph node involvement.2,5 IGM can be seen in any quadrant of the breast except in the subareolar region.6,7 The etiology of IGM is not well delineated, but a localized immune reaction to breast tissue has been proposed.3 The definitive diagnosis can only be established by histopathology.2,6 In this article, we report two cases of IGM seen in a community teaching hospital over a period of one year, and review the etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment options of this under-recognized breast disorder.

Table 1.

Take Home Points About IGM

CASE 1

A 29-year-old African American female, gravida 2 para 2, presented with a 2-month history of a painful right breast mass. There was no discharge or overlying breast skin changes. She delivered her last child 18 months prior to admission and had breast-fed for 9 months. The patient had no significant past medical history and denied previous use of oral contraceptives, estrogens, natural herbs, or recent breast trauma. Review of systems was positive for low-grade fever. Initial cultures of an ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration showed no growth. She had previously received multiple courses of oral antibiotics without improvement. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and parenteral antibiotics.

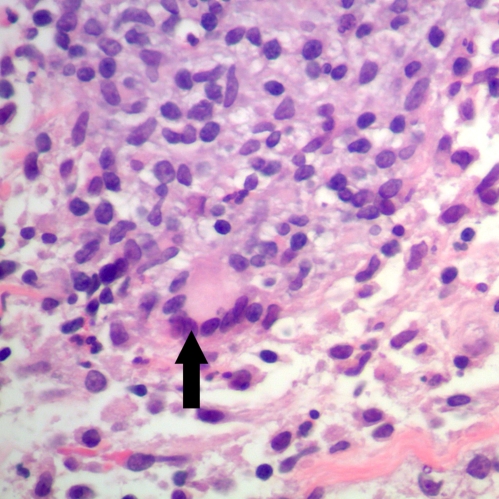

On physical examination the patient was afebrile and there was a 5 by 5 cm hard mass in the upper medial portion of the right breast. The skin overlying the mass was normal and the mass was freely mobile within breast tissue. Axillary lymph nodes were not palpable. Remainder of her physical examination was normal. Vancomycin was instituted on an empiric basis. A repeated ultrasound revealed scattered fluid collection suggestive of small abscesses. A core needle biopsy revealed chronic mastitis with focal abscess formation without infiltrating tumor. The patient failed to improve with antibiotics and subsequently underwent surgical debridement. Cultures and special stains for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi were negative. Pathology showed IGM with multinucleated giant cell and chronic lobulitis (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged on 60 mg of prednisone daily which was tapered to 40 mg by the time of her three week follow-up visit. A decrease in the size of her breast mass was noted at this appointment. With this high dosage of prednisone the patient developed hyperglycemia; therefore, methotrexate was started as a steroid sparing agent. The dosage of prednisone was decreased to 10 mg daily over the next two weeks. Since the patient had an excellent clinical response with complete resolution of the breast mass at the 12-week follow-up visit, prednisone was tapered off completely and methotrexate was discontinued. Five months off of treatment, the patient had no signs or symptoms of breast mass relapse.

Figure 1.

Granulomas with giant cell (Black arrow). (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain, 400X).

CASE 2

A 21-year-old African American female, gravida 1 and para 1, was admitted to the hospital with a one-month history of recurrent breast abscesses. She was seen by her physician who noted an area of induration and erythema in the lateral upper quadrant of the right breast. She was given oral dicloxacillin without any improvement. She was subsequently referred to a breast surgeon who incised and drained purulent material from the lesion; routine cultures were negative. She failed to improve and one week later she was admitted to the hospital. Review of systems was positive for mild bilateral galactorrhea since her last pregnancy 2 years ago and mild weight loss. The patient had no significant past medical history and denied previous use of oral contraceptives, estrogens, natural herbs, or recent breast trauma.

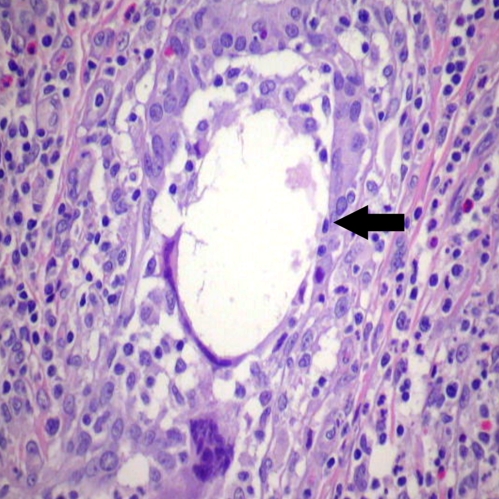

On examination she was afebrile. There was a tender 5 cm right breast mass with superficial erythema. No lymphadenopathy was palpated. Remainder of her physical examination was normal. Vancomycin was started for presumed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infection. Ultrasound showed diffuse interstitial edema with fibro-glandular tissue consistent with inflammation. Repeat incision and drainage showed multiple purulent fluid pockets with subcutaneous extensions. Tissue was sent for histology, special stains, aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial and fungal cultures. Cultures were all negative except one culture that grew a small number of colonies of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; it was considered to be a contaminant. The pathology report showed chronic mastitis and microabscesses. The patient was subsequently released home on linezolid. Two days later the patient was readmitted with a new tender 4 cm breast mass, this time in the left breast. Ultrasound revealed a very complex heterogeneous mass with few areas of hypoechogenicity suggesting an infectious process. The patient underwent excision of the inflammatory mass, with pathology and cultures repeated. Cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi were negative. The biopsies were reported again as chronic mastitis. After considering possibility of IGM, both biopsies were reviewed again by pathologist and interpreted as granulomatous mastitis with perilobular and periductal inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2). The patient was started on 60 mg of prednisone daily. The patient had an excellent clinical response; however, 3 to 4 weeks later she developed a new inflammatory mass in her left breast. Methotrexate was added due to incomplete response to prednisone alone. In spite of 9 months of treatment with steroids and methotrexate, the patient continued to develop new breast masses and chronic suppuration. She subsequently required a bilateral mastectomy.

Figure 2.

Disrupted duct (Black arrow) with multi-nucleated giant cell. (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain, 400 X).

DISCUSSION

IGM usually affects women of childbearing age; however we found reports of patients as young as 11 years-old,8,9 and as old as 80 years.5,10 Most women with IGM report a history of child birth and breastfeeding within the previous 5 years. The true prevalence of IGM is unknown. In a study done by Baslaim et al., histopathological confirmed cases of IGM represented 1.8% of cases out of 1,106 women with benign breast diseases.2 The disease has been found worldwide and in all races, but there is a described predilection for Hispanic and Asian women.2

IGM is an idiopathic condition. Mechanisms that have been proposed as etiologic factors include chemical reaction associated with oral contraceptive pills, autoimmune phenomenon, infection with yet unidentified pathogens, and localized immune response to extravasated secretions from lobules.1,3,4,7,11 Conditions such as pregnancy, breast feeding, breast trauma, hyperprolactinemia with galactorrhea, and alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency have been associated with an increased risk of IGM.8,12–14 An association with local infection with Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii has recently been suggested but remains unconfirmed.13

IGM usually presents with a progressive painful breast lump. The lesions are of variable size, usually firm, tender, ill defined, and unilateral; however bilateral disease is also reported. The lesions are located in any quadrant of the breast except for the subareolar region.6,7 Axillary lymph nodes are usually not enlarged.2 Due to granulomatous inflammation, IGM can cause nipple retraction or peau d’ orange which can mimic a malignant tumor.2 IGM can also mimic breast abscesses since the physical exam and radiological findings are similar.1,2,5,11,14 Patients with chronic IGM can develop fistulae, sterile abscesses, and nipple inversion.3

IGM remains a diagnosis of exclusion and the clinical findings are non-specific. The differential diagnoses includes but is not limited to bacterial mastitis, chronic inflammatory breast disease such as mammary duct ectasia, tuberculous or fungal mastitis, foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis.7,9 The most frequent findings on mammogram and ultrasound are asymmetric diffuse increased density of fibro-glandular tissue and hypoechoic mass lesions or nodular structures, respectively.6 Breast MRI may be a better imaging modality, but it does not allow a differentiation between a granulomatous process and other disorders. Some authors consider MRI to be a promising imaging modality for follow-up of the lesions over time.6 Histopathological evaluation plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of IGM.6

Characteristic histopathology features such as lobular non-caseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and a predominantly neutrophilic background with attendant lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils in varying numbers without necrosis and negative microbiological investigation favor diagnosis of IGM.2,6 Microabscess formation and fat necrosis are frequently seen.2 Not all cases have typical non-caseating granulomas on histopathological exam. However, all patients have epithelioid histiocytes present within the smears, and some authors have suggested that the presence of epithelioid histiocytes should alert the cytopathologist to the possibility of IGM.6 The absence of caseating necrosis and predominant neutrophilic background are important clues favoring a diagnosis of IGM.6

The treatment of IGM remains controversial. The available treatment options include close follow-up, immunosuppressive drugs, and surgical excision. Patients with uncomplicated IGM may be observed over time without treatment.5,7,15 Eric et al. reported spontaneous resolution in 50% of cases of IGM in their study without any treatment with a mean interval of complete resolution of 14.5 months (range 2–24 months).5 Antibiotics have no role in the management of true cases of IGM.16 The use of corticosteroids was first proposed by Dehetrogh et al.17 Several case series have also reported successful use of corticosteroids in the treatment of IGM.9,18–22 Steroids should be started at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day and tapered slowly according to clinical response.20 It may be necessary to continue high doses of steroid until the lesions completely resolve. Responses usually occur within weeks of treatment, but patients may need to be treated for several months.5,20 About half of the cases relapse after stopping or decreasing the dose of steroids.18,20 The use of steroid sparing agents such as methotrexate or azathioprine provide options that may facilitate tapering of steroids.18,23

Traditionally IGM was treated by surgical excision of the mass, but some studies have suggested that the recurrence rate with surgical treatment is higher than with steroid treatment.12,24,25 Recurrence rates of 5% to 50% are reported after surgical excision of mass.10,15 Wide excisions with negative margins are better than limited excision alone, as there is a higher tendency to relapse after limited excision.6,19 Furthermore, there is a high rate of fistula formation, poor wound healing and disfigurement after surgical intervention in patients with IGM.5 A retrospective review of cases seen over 25 years by Al-Khaffaf et al. showed that regardless of therapeutic intervention, which included steroids, antibiotics, and surgical intervention alone or in combinations, the condition takes about 6 to 12 months to resolve completely.1 In our experience, one patient responded very well to steroids, while the other required bilateral mastectomy. We are aware of only three other cases that required complete mastectomy.7,8,16,18

In summary, IGM is a disorder that may be encountered in a general practice, and that may mimic breast carcinoma or abscess. We report two cases of IGM and describe the clinical presentation, diagnosis, evaluation and management of this disorder. The diagnose of IGM should be considered in women who develop recurrent sterile breast abscesses and appropriate diagnostic evaluation should be performed on such cases.

Acknowledgments

There are no internal or external conflicts of interest to report.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Kessler E, Wolloch Y. Granulomatous mastitis: A lesion clinically simulating carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1972;58:642–646. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/58.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baslaim MM, Khayat HA, Al-Amoudi SA. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: A heterogeneous disease with variable clinical presentation. World J Surg. 2007;31:1677–1681. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown KL, Tang PH. Postlactational tumoral granulomatous mastitis: A localized immune phenomenon. Am J Surg. 1979;138:326–329. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmalt HL, Ramsey-Stewart G. Granulomatous mastitis. Med J Aust. 1981;1:356–359. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb135631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai EC, Chan WC, Ma TK, Tang AP, Poon CS, Leong HT. The role of conservative treatment in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:454–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akcan A, Akyildiz H, Deneme MA, Akgun H, Aritas Y. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: A complex diagnostic and therapeutic problem. World J Surg. 2006;30:1403–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imoto S, Kitaya T, Kodama T, Hasebe T, Mukai K. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: Case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1997;27:274–277. doi: 10.1093/jjco/27.4.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, Shatnawi NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: Time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J. 2004;10:318–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz U, Molad Y, Ablin J, et al. Chronic idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1108:603–608. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asoglu O, Ozmen V, Karanlik H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:108–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cserni G, Szajki K. Granulomatous lobular mastitis following drug-induced galactorrhea and blunt trauma. Breast J. 1999;5:398–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.1999.97040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakurai T, Oura S, Tanino H, et al. A case of granulomatous mastitis mimicking breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer. 2002;9:265–268. doi: 10.1007/BF02967601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad S, Jones WO, Holland DJ. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology. 2003;35:109–119. doi: 10.1080/0031302031000082197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Khaffaf B, Knox F, Bundred NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: A 25-year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schelfout K, Tjalma WA, Cooremans ID, Coeman DC, Colpaert CG, Buytaert PM. Observations of an idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:260–262. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(00)00546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson JP, Massoll N, Marshall J, Foss RM, Copeland EM, Grobmyer SR. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: In search of a therapeutic paradigm. Am Surg. 2007;73:798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeHertogh DA, Rossof AH, Harris AA, Economou SG. Prednisone management of granulomatous mastitis. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:799–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010023031406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Tymms KE, Buckingham JM. Methotrexate in the management of granulomatous mastitis. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:247–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2002.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayeva-Derman M, Perrotin F, Lefrancq T, Roy F, Lansac J, Body G. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Review of the literature illustrated by 4 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1999;28:800–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azlina AF, Ariza Z, Arni T, Hisham AN. Chronic granulomatous mastitis: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. World J Surg. 2003;27:515–518. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg J, Baute L, Storey L, Park P. Granulomatous mastitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:813–815. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newnham MS, Shirley SE, McDonald AH. Granulomatous lobular mastitis. A case report and review of the literature. West Indian Med J. 2001;50:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raj N, Macmillan RD, Ellis IO, Deighton CM. Rheumatologists and breasts: Immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatous mastitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:1055–1056. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen MB, Nielsen DM. Diagnosis and treatment of granulomatous mastitis. Am J Med. 1992;93:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato N, Yamashita H, Kozaki N, et al. Granulomatous mastitis diagnosed and followed up by fine-needle aspiration cytology, and successfully treated by corticosteroid therapy: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1996;26:730–733. doi: 10.1007/BF00312095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]