Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship of mild traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and post-concussive symptoms (PCS) to post injury family burden and parental distress, using data from a prospective, longitudinal study.

Methods

Participants included 71 children with mild TBI with loss of consciousness (LOC), 110 with mild TBI without LOC, and 97 controls with orthopedic injuries not involving the head (OI), and their parents. Shortly after injury, parents and children completed a PCS interview and questionnaire, and parents rated premorbid family functioning. Parents also rated family burden and parental distress shortly after injury and at 3 months post injury.

Results

Mild TBI with LOC was associated with greater family burden at 3 months than OI, independent of socioeconomic status and premorbid family functioning. Higher PCS shortly after injury was related to higher ratings of family burden and distress at 3 months.

Conclusions

Mild TBI are associated with family burden and distress more than mild injuries not involving the head, although PCS may influence post injury family burden and distress more than the injury per se. Clinical implications of the current findings are noted in the Discussion section.

Keywords: children, family burden, mild traumatic brain injury, parental distress, post-concussive symptoms

Introduction

Although ∼1,000,000 traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are sustained annually by children in the United States, the majority of brain injuries can be classified as mild, whereas severe TBI are relatively uncommon (Kraus, 1995). The annual incidence of mild TBI, based on emergency department reports, is ∼500,000 for children below the age of 15 years (Bazarian et al., 2005). Studies show that mild TBI can have life-long cognitive, somatic, emotional and behavioral symptoms, and other deleterious outcomes (Chesnut et al., 1999). Yet, limited data exist on the relationship between mild TBI and the family. To our knowledge, studies have not yet examined whether mild TBI is associated with family burden and parental distress. Therefore, we have relied on the studies that have examined the relationship between moderate to severe TBI and family burden and distress to guide the hypotheses of the current study.

Severe TBI in childhood adversely affect the family (Rivara et al., 1994; Rivara et al., 1996; Wade, Taylor, Drotar, Stancin, & Yeates, 1996). The families of children with severe TBI frequently report increased family burden, injury-related stress, and parental psychological distress in comparison to the families of healthy children and children with orthopedic injuries (OI) not involving the head (Kinsella et al., 1995; Wade, Taylor, Drotar, Stancin, & Yeates, 1998). Rivara and colleagues examined the impact of mild, moderate, and severe TBI on the family (Rivara et al., 1994, 1996). From 1 to 3 years post injury, few changes to the family occurred for children with mild TBI, while considerable deterioration was observed in the severe group. Unfortunately, these studies did not compare the impact of the injury on the families of children with mild TBI to the families of children with OI or healthy children. Therefore, we cannot be certain about the nature and degree of the relationship between mild TBI and the family post injury, hence the need for the current study.

Brain injury alone may not account for family burden and distress; children's deficits are also likely to affect the family following injury. Children with mild TBI are frequently reported to exhibit the onset of cognitive, somatic, emotional, and behavioral problems, or post-concussive symptoms (PCS) (Mittenberg, Miller, & Luis, 1997a; Yeates et al., 1999). Examples of PCS include impaired concentration, memory problems, slow information processing, irritability, headaches, dizziness, blurred vision, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and noise and light sensitivity. Mittenberg et al. (1997a) found that children who had sustained mild TBI reported more subjective symptoms after six weeks than those with OI. Anxiety and conduct problems have also been identified among children after hospitalization for mild TBI (Asarnow, Satz, & Light, 1991). Moreover, in a small proportion of children with mild TBI, PCS persist over a considerable period of time (Yeates et al., 1999). The neurobehavioral deficits following mild TBI may be related to increased family burden and distress. Similar relations have been observed between the cognitive, academic, and adaptive difficulties following moderate to severe TBI and family burden and distress (Kinsella et al., 1995; Max et al., 1998; Taylor et al., 2001; Wade et al., 1998; Yeates, 2000). However, no previous study has empirically examined the relationship of children's PCS following mild TBI to family burden and parental distress.

The overall goal of the current study was thus to examine the association between mild TBI in children and family burden and parental distress, and to determine the contributions of children's PCS to family burden and parental distress. Because injury severity is related to family burden and distress in children with more severe TBI (Wade et al., 1998), we also examined whether severity matters even among injuries classified as mild TBI. Loss of consciousness (LOC) is a major variable in grading systems of concussion and an important indicator of injury severity (American Academy of Neurology, 1997). We therefore divided the mild TBI group into children with LOC and those without LOC, and compared their ratings to children with OI. Further, our previous research found that socioeconomic status (SES) and premorbid family functioning are significant predictors of family burden and distress following moderate to severe TBI (Wade et al., 1998); therefore, SES and premorbid family functioning were included in the current analyses as covariates. We hypothesized that the parents of children with mild TBI accompanied by LOC would report greater family burden and parental distress than the parents of children with OI, after controlling for SES and premorbid family functioning. We also hypothesized that parent- and child-rated PCS shortly after injury would account for significant variance in post injury family burden and parental distress, over and above group membership, and after controlling for SES and premorbid family functioning.

Methods

Study Design and Recruitment

Data were collected as part of a prospective longitudinal study that included children with mild TBI or OI and their families (Yeates & Taylor, 2005). Potential participants were recruited from two children's hospitals in Ohio, The Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, and the Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital in Cleveland. Participants were identified from consecutive admissions to each hospital's Emergency Department. After written informed consent (approved by each hospital's Institutional Review Board) was obtained from parents, children and their parents completed a baseline assessment shortly after injury (i.e., no later than two weeks post injury) and a second assessment three months post injury. Children and their parents were provided with modest monetary compensation following each assessment.

Participants

Children with mild TBI were eligible to participate in the study if they sustained a blunt head trauma and demonstrated at least one of the following indications of concussion: an observed LOC; a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; Teasdale & Jennett, 1974) score of 13 or 14; or at least two acute symptoms of concussion as noted by Emergency Department medical personnel. Acute symptoms of concussion included persistent post-traumatic amnesia, disorientation of person, place, or time, transient neurological deficits, vomiting, nausea, headache, diplopia, and dizziness. Children with mild TBI were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: LOC lasting >30 minutes; GCS score of <13; delayed neurological deterioration; or any medical contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Potential participants were not excluded if they required hospitalization or demonstrated intracranial lesions or skull fractures on acute computerized tomography (CT) scans.

Children were eligible to be included in the OI group if they had sustained upper or lower extremity fractures associated with an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS; American Association for Automotive Medicine, 1990) score of 3 or less. They were excluded if they displayed any evidence of head injury or symptoms of concussion.

Potential participants in both groups were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: neurosurgical or surgical intervention; injury with an AIS score of greater than 3; injury that interferes with neuropsychological testing (e.g., fracture of preferred upper extremity); hypoxia; hypotension; shock during or following the injury; ethanol or drug ingestion involved with the injury; documented history of previous head injury requiring medical treatment; premorbid neurological disorder or mental retardation; injury determined to be the result of child abuse or assault; or a history of severe psychiatric disorder requiring hospitalization.

All children between the ages of 8 and 15 years who presented for evaluation of mild TBI or OI were screened to determine if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The rate of participation among children eligible for the mild TBI group was 48%; the rate of participation among those eligible for the OI group was 35%. Demographic information including census tract data (Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council Geocoding System, 2003, 2005) was compiled for both participants and non-participants. Within the mild TBI and OI groups, participants and non-participants did not differ significantly in age, gender, ethnic/racial minority status, or census tract measures of SES (i.e., mean family income, percentage of minority heads of household, and percentage of households below the poverty line).

The total sample included 285 children, 186 with mild TBI and 99 with OI. For the purposes of the current study, seven participants were excluded because a different parent or guardian had completed the measures of family burden and parental distress at the two assessment occasions. Thus, the sample for the current study included 278 children, 181 with mild TBI and 97 with OI. All but eight of the participants returned for the 3-month assessment. The mild TBI and OI groups differed significantly on overall injury severity as measured by the Modified Injury Severity Score, which is derived from AIS scores (American Association for Automotive Medicine, 1990). Recreational and sport-related injuries were the most common causes of injury in both groups; transportation-related injuries occurred more commonly among the mild TBI group than the OI group.

The mild TBI group was further divided into two groups representing those with and without LOC; 39% had an observed LOC, usually of very brief duration (median = 1 minute, range = 1–15). The presence or absence of LOC is often used as a criterion to grade the severity of concussion (American Academy of Neurology, 1997) and we were interested in determining whether the severity of mild TBI was related to family burden and parental distress. The groups did not differ significantly in age at injury, gender, ethnic/racial minority status, or SES, as shown in Table I. SES was assessed using the Duncan Occupational Status Index (Stevens & Featherman, 1981), which reflects occupational status. Higher scores reflect higher SES.

Table I.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | OI | TBI without LOC | TBI with LOC |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 97 | 110 | 71 |

| Gender (% male) | 64.9 | 68.2 | 77.5 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 65 | 71 | 69 |

| Socioeconomic status,a M (SD) | 39.39 (19.85) | 39.03 (19.13) | 39.32 (18.00) |

| Age at injury (in years), M (SD) | 11.75 (2.21) | 11.83 (2.25) | 12.19 (2.20) |

| Age at assessment (in years), M (SD) | 11.78 (2.22) | 11.86 (2.25) | 12.22 (2.20) |

| GCS score, M (SD) | NA | 14.89 (0.37) | 14.86 (0.42) |

| Days before baseline assessment,b M (SD) | 11.19 (3.62) | 11.60 (3.25) | 11.21 (3.42) |

| Hospital admissions, % | 0 | 22.7 | 43.7 |

TBI, traumatic brain injury; LOC, loss of consciousness; OI, orthopedic injury; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Socioeconomic status was assessed using the Duncan Socioeconomic Composite Index.

Number of days between date of injury and baseline assessment.

Measures

Premorbid Family Functioning

Parents completed the Family Assessment Device (FAD; Miller, Bishop, Epstein, & Keitner, 1985) at the baseline assessment as a retrospective measure of premorbid family functioning. This 60-item self-report measure has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity (Miller et al., 1985). The 12-item General Functioning (GF) scale was used in the current study as the measure of premorbid family functioning. The inter-item reliability based on the current sample was .86 for both the total sample and the mild TBI group, and .84 for the OI group.

Post Injury Family Functioning

Family burden was assessed using the Family Burden of Injury Interview (FBII; Burgess et al., 1999), which was administered at baseline and 3-month assessments. The FBII is a structured interview designed to measure the stress that families experience following a child's injury. The FBII consists of 30 questions about injury-related burden in four areas: (a) concerns with adjustment and recovery of the child; (b) reactions of extended family members and friends; (c) reactions of the spouse and sibling(s); and (d) changes in family routine. For each question, parents are first asked to report the presence or absence of injury-related burden. For each question to which they respond affirmatively, they then rate the amount of stress they experience on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (no stress) to 4 (extremely stressful). The FBII yields summary scores for Child, Spouse, Siblings, Routines, and Extended Family and Friends scales. For the purpose of this study, we used a composite score derived from factor analysis that represents the mean of the Child, Spouse, and Extended Family and Friends scales (Burgess et al., 1999). The Siblings and Routines scales were excluded because past analyses suggested that they were not factorially invariant for mild TBI and OI groups. For caregivers without spouses, the average of the other two scales was used as the composite score. The FBII has shown satisfactory reliability and validity in previous research on TBI (Burgess et al., 1999; Taylor et al., 2001; Wade et al., 1998). The inter-item reliability based on the current sample was .72 for the total sample, and .71 and .73 for the mild TBI and OI groups, respectively.

Parental Distress

Parental distress was assessed using the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), which also was administered at baseline and 3-month assessments. This is a widely used self-report measure that assesses psychological symptoms across nine dimensions. Parents rate the amount of distress they experience on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all distressed) to 4 (extremely distressed). In the current study, we used the Global Severity Index of the BSI to provide a summary measure of parental distress. The BSI has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), and has been successfully employed in previous studies on TBI (Wade et al., 1998; Yeates et al., 2002). In the present study, the inter-item reliability for the total sample as well as the mild TBI group was .96, and .97 for the OI group.

Post-concussive Symptoms

Children's PCS were assessed using the Post-Concussive Symptoms (PCS) Interview (Mittenberg, Miller, & Luis, 1997; Mittenberg, Wittner, & Miller, 1997), which asks parents and children to report the presence or absence during the preceding week of 15 cognitive, somatic, and emotional symptoms. The 15 items were: have you been tired a lot, have you had headaches, have you had trouble remembering things, has bright light hurt your eyes, have you felt like your head was spinning, felt cranky, felt nervous or scared (or like you had butterflies in your stomach), have you had trouble paying attention, felt sad (like wanting to cry), has it been hard for you to think, have you had trouble seeing, has loud noise hurt your ears, have you had trouble sleeping, have you been less interested in doing things, and have you been acting like a different person. These symptoms are similar to those listed for the Post-Concussion Syndrome in the International Classification of Diseases (ICS-10; World Health Organization, 1992) and as research diagnostic criteria for Post-concussional Disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The interview has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in previous research (Mittenberg, Miller, & Luis, 1997; Mittenberg, Wittner, & Miller, 1997). In the current study, the inter-item reliability on the parent-rated PCS Interview was .71 for the total sample, and .60 and .82 for the mild TBI and OI groups, respectively. On the child-rated PCS Interview, the inter-item reliability was .70 for the total sample, and .71 and .68 for the mild TBI and OI groups, respectively.

More specific dimensions of PCS were assessed using the Health and Behavior Inventory (HBI), which was completed by children and parents at the baseline assessment. This 50-item rating scale requires parents and children to rate the frequency of occurrence of each symptom over the past week on a 4-point scale, ranging from “never” to “often.” The HBI was developed based on previous research involving children with moderate to severe TBI (Barry, Taylor, Klein, & Yeates, 1996; Yeates et al., 2001), as well as on a review of similar checklists used in adult studies of PCS (Axelrod et al., 1996; Cicerone & Kalmar, 1995; Gerber & Schraa, 1995; Gouvier, Cubic, Jones, Brantly, & Cutlip, 1992). An earlier version of the HBI was used in a previous study of PCS in children with mild TBI (Yeates et al., 1999). Factor analyses of the HBI have yielded cognitive and somatic dimensions of PCS that are stable across parent and child ratings (Ayr et al., 2005), and factor scores representing those dimensions were used in this study. The inter-item reliability on the parent-rated Cognitive Symptoms scale was .94 for the total and mild TBI groups, and .93 for the OI group, and .80 for the total and mild TBI groups, and .81 for the OI group on the parent-rated Somatic Symptoms scale. The inter-item reliability on the child-rated Cognitive Symptoms scale was .89, .90, and .88 for the total, mild TBI and OI groups, respectively, and .86 for the total and mild TBI groups and .85 for the OI group on the child-rated Somatic Symptoms scale.

Data Analyses

Group differences in family burden and parental distress across the first 3 months post injury were examined using multivariate repeated-measures analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), with group and time (i.e., baseline and 3 months post injury) as independent variables. To control for family SES and premorbid family functioning, the Duncan Occupational Status Index and the FAD General Functioning scale were included as covariates in all analyses. Planned contrasts were conducted to compare each of the mild TBI groups (i.e., with and without LOC) to the OI group. Effect sizes were assessed using η2 for overall group differences and Cohen's d for planned contrasts.

We examined the relationship of PCS to family burden and parental distress by conducting similar MANCOVA, with group, PCS, and time as independent variables. Six MANCOVAs were performed for each outcome measure (i.e., FBII and BSI), each using a different variable to represent PCS (i.e., the PCS Interview and the HBI Cognitive and Somatic Symptom scales as rated by both participants and their parents). If the three-way interaction (i.e., group by PCS by time) was not significant, the interaction term was trimmed from the model and the analysis was repeated. The analyses were intended to determine whether PCS shortly after injury is a significant predictor of family burden and parental distress across 3 months and account for any group differences in family burden and parental distress.

Results

Group comparisons on the measures of family burden and parental distress are summarized in Table II. Although the main effect of group was not significant for the FBII, planned contrasts showed that the mild TBI with LOC group reported higher overall family burden than the OI group (d = .37, p = .04). Neither the overall main effect of group nor the planned contrasts were significant for the BSI.

Table II.

Analyses of Group Differences in Family Burden and Parental Distress

| Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OI | Mild TBI without LOC | Mild TBI with LOC | Group F-valuea | η2 | |

| M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Family Burden and Parental Distress | |||||

| FBII | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 2.21 | 0.02 |

| BSI | 49.76 (0.97) | 49.27 (0.89) | 49.93 (1.09) | 0.88 | 0.00 |

Derived from multivariate repeated-measures ANCOVAs; degrees of freedom = (2, 256).

Marginal means and standard errors estimated in full model, which included group (OI, Mild TBI without LOC, Mild TBI with LOC) and time as independent variables and the FAD General Functioning scale and the SCI as covariates.

OI, orthopedic injury; FBII, Family Burden of Injury Interview; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; η2, partial eta-squared (proportion of variance explained).

The analyses involving measures of PCS as predictors of family burden and parental distress are summarized in Tables III and IV. The three-way interaction terms involving group, PCS, and time were not significant for either the FBII or BSI. When the three-way interaction term was trimmed from the models, the PCS by time interaction was significant for the FBII when parent ratings on the PCS Interview and both HBI symptom scales were used to measure PCS. No other interactions between parent-rated PCS and time were significant. The interactions between child ratings of PCS and time were not significant for either the FBII or BSI.

Table III.

Analyses of the Family Burden of Injury Interview with Group and PCS as Predictors

| Predictors | Group | PCS | Group × Time | PCS × Time | PCS × Group | Group × PCS × Time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | |

| Parent-rated PCS | |||||||||||||

| PCS Interview | 260 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 56.82 | 0.18 | 3.83 | 0.02 | 54.54 | 0.18 | 1.93 | 0.01 | 1.24 | 0.01 |

| HBI cognitive symptoms | 261 | 1.21 | 0.01 | 9.96 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 14.76 | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.00 |

| HBI somatic symptoms | 261 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 18.23 | 0.07 | 2.05 | 0.01 | 20.98 | 0.08 | 2.64 | 0.01 | 1.21 | 0.01 |

| Child-rated PCS | |||||||||||||

| PCS Interview | 259 | 3.54 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| HBI cognitive symptoms | 261 | 2.56 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.00 |

| HBI somatic symptoms | 261 | 1.84 | 0.01 | 1.48 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.33 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

Significant effects (p < .05) are italicized. The main effects for time, FAD, and SCI and interactions involving FAD × Time and SCI × Time are not listed in the table because they were not of primary interest, but they were included in the model tested.

PCS, post-concussive symptoms; PCS Interview, Post-Concussive Symptom Interview; HBI, Health and Behavior Inventory.

Table IV.

Analyses of the Brief Symptom Inventory with Group and PCS as Predictors

| Predictors | Group | PCS | Group × Time | PCS × Time | PCS × Group | Group × PCS × Time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | |

| Parent-rated PCS | |||||||||||||

| PCS Interview | 260 | 2.16 | 0.01 | 31.15 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 3.98 | 0.02 |

| HBI cognitive symptoms | 261 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 32.87 | 0.11 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 4.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| HBI somatic symptoms | 261 | 3.10 | 0.01 | 34.80 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 8.41 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.00 |

| Child-rated PCS | |||||||||||||

| PCS Interview | 259 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 4.48 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.00 |

| HBI cognitive symptoms | 261 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| HBI somatic symptoms | 261 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 8.76 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.89 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

Significant effects (p < .05) are italicized. The main effects for time, FAD, and SCI and interactions involving FAD × Time and SCI × time are not listed in the table because they were not of primary interest, but they were included in the model tested.

PCS, post-concussive symptoms; PCS Interview, Post-Concussive Symptom Interview; HBI, Health and Behavior Inventory.

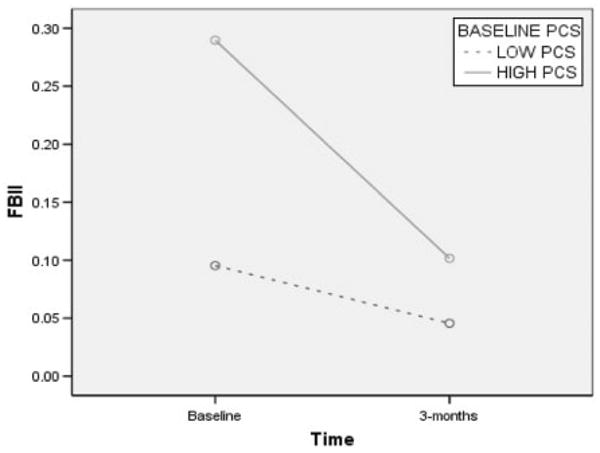

In all instances, when the PCS by time interaction was significant, higher PCS were associated with greater perceived family burden, but the relationship was stronger at the baseline assessment, for example (r = .50, p = .001) for the parent-rated PCS Interview, than at the 3-month assessment (r = .22, p = .001). Put another way, differences in perceived family burden between children with high versus low levels of baseline PCS tended to decrease over time (e.g., for the parent-rated PCS Interview, F = 42.05, η2 = .13, p = .001 at baseline, and F = 7.40, η2 = .03, p = .007 at 3 months). An example of a significant PCS by time interaction is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Post-concussive symptoms by time interaction.

The main effect for PCS was significant for both the FBII and BSI when using parent ratings on all three measures of PCS. However, when using child-rated measures of PCS, the main effect for PCS was significant for only the BSI. In general, higher ratings of PCS as reported by both parents and children shortly after injury were associated with greater perceived family burden and parental distress at 3 months.

The group difference between children with mild TBI accompanied by LOC and those with OI on the FBII was no longer significant when any of the parent ratings of PCS or children's ratings of somatic symptoms on the HBI were included in the analyses as independent variables. However, the group difference on the FBII remained significant when the children's ratings on the PCS Interview and their ratings of cognitive symptoms on the HBI were included as independent variables.

The PCS by group interaction was significant for the BSI for parent ratings of somatic symptoms on the HBI, but not for any other measures of PCS (Table IV). Contrary to expectations, the parents of children with OI reported greater parental distress than the parents of children in the two mild TBI groups, and the differences were more pronounced when parents reported higher levels of PCS on the HBI Somatic Symptoms scale.

Discussion

The current findings indicate that, in general, family burden and parental distress following mild TBI is circumscribed. This is consistent with previous research showing that whereas moderate to severe TBI in children adversely affect the family (Rivara et al., 1994, 1996), mild TBI are less likely to alter family burden and distress from premorbid levels. The scores on the BSI, for instance were within the non-clinical range suggesting adequate adjustment among the families of children with mild TBI. Because the level of family burden as reported by the parents in this study was very low, the range was restricted. For most of the families, neither mild TBI nor OI resulted in significant family burden; however, the parents of children with mild TBI accompanied by LOC reported greater family burden than the parents of children with OI. Thus, mild TBI that are of relatively greater severity may involve family burden. A closer examination of parents' responses on the Family Burden of Injury Interview indicated that most of the family burden was related to parental concerns about the child's recovery from the injury. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that even when children sustain minor head trauma, parents report anxiety and apprehension about post injury recovery and adjustment (Casey, Ludwig, & McCormick, 1986, 1987).

The group difference in family burden occurred over and above SES and premorbid family functioning. Notably, though, the group difference was no longer significant when parent-rated measures of PCS and child ratings on some of the measures of PCS were taken into account. Moreover, parent ratings of children's PCS accounted for significant unique variance in family burden and parental distress, over and above SES, premorbid family functioning, and group membership. This was the case as much as 3 months post injury in both children with mild TBI and those with OI. Higher ratings of PCS were related to higher levels of both family burden and parental distress. These results suggest that children's PCS shortly after a minor injury may be a more powerful source of post injury family burden and distress than the injury per se. This finding is consistent with studies that have demonstrated the relationship of neurobehavioral and psychosocial deficits to family burden and distress following moderate and severe TBI (Max et al., 1998).

The only unexpected finding in the study was the PCS (parent-rated HBI Somatic Symptoms scale) by group interaction, which was significant for the measure of parental distress (i.e., BSI). The explanation for this interaction is unclear. In the absence of any other significant findings of a similar nature, the interaction appears to be an isolated finding that could be spurious.

The relations between parent-rated PCS and measures of family burden and distress are confounded in part by shared rater and method variance because parents rated both PCS and family burden and distress. On the other hand, children's ratings of PCS also predicted significant variance in parental distress. Although the latter relationship was not significant at 3 months, the overall pattern suggests that the association between PCS and post injury family burden and distress may not be entirely tainted by shared rater variance; however, shared method variance may still account for some of the findings.

Although the effect sizes in this study were small, the findings add to our knowledge regarding family burden and distress following mild TBI in school-age children, and may be important in clinical practice. Overall, the results are encouraging, suggesting that family burden and parental distress following mild TBI is typically limited. Casey et al. (1986) commented that due to the lack of information on the impact of mild TBI on the child and family, pediatricians often depend on, and provide families with information that is based on the outcomes of more severe TBI. The current findings may help clinicians from being overly vigilant, and also help them reassure the families that the stress associated with the mild TBI, in most instances, will be mild and short-lived. However, the present findings also show that families may suffer as a function of the PCS shortly after a mild TBI. This finding has important clinical implications. First, children should be assessed for PCS shortly after injury in routine clinical assessments. This will allow pediatric professionals to inform parents about the risks that they and their child may face following mild TBI (Casey et al., 1986). Further, efforts to improve the well-being of families following mild TBI may need to consider methods to reduce children's PCS, which in turn may alleviate associated family burden and parental distress.

Acknowledgments

The research presented here was supported by Grants HD39834 and HD44099 from the National Institutes of Health to Keith Owen Yeates. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Lauren Ayr, Anne Birnbaum, Amy Clemens, Taryn Fay, Amanda Lininger, Nori Minich, Katie Pestro, Elizabeth Roth, Elizabeth Shaver, and Heidi Walker to the conduct of the research.

Footnotes

A preliminary version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society in Portland, Oregon, February, 2007.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: The management of concussion in sports (summary statement) Neurology. 1997;48:581–585. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association fo Automotive Medicine. The abbreviated injury scale (AIS) – 1990 revision. Des Plaines, IL: American Association for Automotive Medicine; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow RF, Satz P, Light R. Behavior problems and adaptive functioning in children with mild and severe closed head injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1991;16:543–555. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod B, Fox DD, Less-Haley PR, Earnest K, Dolezal-Wood S, Goldman RS. Latent structure of the Postconcussion Syndrome Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ayr LK, Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Browne M, Bangert B, Dietrich A, et al. Dimensions of post-concussive symptoms in children with mild head injuries [Abstract] International Neuropsychological Society 34th Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2005;202 [Google Scholar]

- Barry CT, Taylor HG, Klein S, Yeates KO. The validity of neurobehavioral symptoms reported in children after traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychology. 1996;2:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarian JJ, McClung J, Shah MN, Cheng YT, Flesher W, Kraus J. Mild traumatic brain injury in the United States, 1998 – 2000. Brain Injury. 2005;19:85–91. doi: 10.1080/02699050410001720158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess ES, Drotar D, Taylor HG, Wade S, Stancin T, Yeates KO. The Family Burden of Injury Interview (FBII): Reliability and validity studies. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1999;14:394–405. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199908000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey R, Ludwig S, McCormick MC. Morbidity following minor head trauma in children. Pediatrics. 1986;78:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey R, Ludwig S, McCormick MC. Minor head trauma in children: An intervention to decrease functional morbidity. Pediatrics. 1987;80:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnut RM, Carney N, Maynard H, Mann NC, Patterson P, Helfand M. Summary report: Evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1999;14:176–188. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone KD, Kalmar K. Persistent postconcussion syndrome: The structure of subjective complaints after mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1995;10:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council Geocoding System. 2003 Retrieved September 1, 2001–December 31, 2004, from http://www.ffiec.gov/Geocode/default.htm.

- Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council Geocoding System. 2005 Retrieved January 1, 2005–November 1, 2005, from http://www.ffiec.gov/Geocode/default.htm.

- Gerber DJ, Schraa JC. Mild traumatic brain injury: Searching for the syndrome. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1995;10:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvier WD, Cubic B, Jones G, Brantley P, Cutlip Q. Postconcussion symptoms and daily stress in normal and head-injured college populations. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1992;7:193–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella G, Prior M, Sawyer M, Murtagh D, Eisenmajer R, Anderson V, et al. Neuropsychological deficit and academic performance in children and adolescents following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1995;20:753–767. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JF. Epidemiological features of brain injury in children: Occurrence, children at risk, cause, & manner of injury, severity, & outcomes. In: Broman SH, Michel ME, editors. Traumatic brain injury in children. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Max JE, Castillo CS, Robin DA, Lindgren SD, Smith WL, Sato Y, et al. Predictors of family functioning after traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I, Bishop D, Epstein N, Keitner G. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Mittenberg W, Miller LJ, Luis CA. Postconcussion syndrome persists in children. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1997;11305 [Google Scholar]

- Mittenberg W, Wittner MS, Miller LJ. Postconcussion syndrome occurs in children. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:447–452. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara J, Jaffe K, Polisar N, Fay G, Lioa S, Martin K. Predictors of family functioning and changes three years after traumatic brain injury in children. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1996;77:754–764. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara J, Jaffe K, Polissar N, Fay G, Martin K, Shurtleff H, et al. Family functioning and children's academic performance and behavior problems in the year following traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994;75:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Featherman DL. A revised socioeconomic index of occupational status. Social Science Research. 1981;10:364–395. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Drotar D, Stancin T, Burant C. Bidirectional child-family influences on outcomes of traumatic brain injury in children. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2001;7:755–767. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701766118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Stancin T, Yeates KO. Childhood traumatic brain injury: Initial impact on the family. Journal of Learning disabilities. 1996;29:653–661. doi: 10.1177/002221949602900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Stancin T, Yeates KO. Family burden and adaptation during the initial year after traumatic brain injury in childhood. Pediatrics. 1998;102:110–116. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICS-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KO. Closed-head injury. In: Yeates KO, Ris MD, Taylor HG, editors. Pediatric neuropsychology: Research, theory and practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KO, Taylor HG. Neurobehavioral outcomes of mild head injury in children and adolescents. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2005;8:5–16. doi: 10.1080/13638490400011199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Barry CT, Drotar D, Wade SL, Stancin T. Neurobehavioral symptoms in childhood closed-head injuries: Changes in prevalence and correlates during the first year post-injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:79–92. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Woodrome SE, Wade SL, Stancin T, Drotar D. Race as a moderator of parent and family outcomes following pediatric traumatic brain injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:393–403. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates KO, Luria J, Bartkowski H, Rusin J, Martin L, Bigler ED. Post-concussive symptoms in children with mild closed-head injuries. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1999;14:337–350. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]