Abstract

For multisensory processing to occur, inputs from different sensory modalities must converge onto individual neurons. Traditionally, multisensory neurons have been identified as those, which were independently activated by more than one sensory modality. Recently, a different multisensory search paradigm has revealed neurons in somatosensory and visual cortex that were activated by only a single modality, whose responses were significantly affected by the presence of a second modality cue. These experiments recorded neurons in the cat auditory field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus that also met this criterion, suggesting that subthreshold forms of multisensory processing may represent a general feature of multisensory systems.

Keywords: convergence, cortex, electrophysiology, visual

Introduction

For nearly half a century [1], the bimodal neuron has been regarded as the sole arbiter of multisensory processing. This form of multisensory convergence is represented by inputs from more than one sensory modality, each of which can independently activate the target neuron. Recently, a ‘new’ form of multisensory neuron has been identified that is excited to suprathreshold levels by only one sensory modality, yet inputs from a second modality can significantly modulate these responses through facilitation or suppression. Examples of subthreshold multisensory effects have been specifically described in somatosensory (area SIV; [2]) and visual (posterolateral lateral suprasylvian; [3,4]) cortex, as well as in ancillary observations from other cortical areas [5,6]. These disparate observations suggest that subthreshold multisensory processing may be a general feature of multisensory systems. To test that notion, this experiment sought to examine the auditory cortical field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES) for the presence of subthreshold multisensory effects.

First identified by Clarey and Irvine [7], neurons in the FAES region prefer complex sounds containing multiple frequencies and show sensitivity to sound location [8,9], and reversible deactivation of the FAES leads to behavioral deficits in sound localization [10]. Accordingly, the FAES has strong connections with the superior colliculus [11,12] where auditory [11] as well as multisensory [12,13] responses are dependent on inputs from the FAES. The FAES is also bordered anteriorly by a somatosensory field (area SIV; [14]) and ventrally by the visual area of the ectosylvian sulcus (AEV; [15]), and bimodal neurons have been identified largely along these shared borders [16]. In contrast to unimodal neurons, subthreshold multisensory neurons have not been identified in this region. Given that a newly devised multisensory search paradigm ([2], modified by [3]) has uncovered nonbimodal forms of multisensory processing in visual and somatosensory cortices, it seems possible that similar forms of multisensory convergence might be uncovered in the FAES. Such an observation would support the notion that subthreshold-processing patterns might be ubiquitous to multisensory systems as well as provide further evidence that multisensory processing is subserved by not just bimodal neurons, but by a range of multisensory convergence patterns.

Methods

All procedures were performed in compliance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication 86-23), the National Research Council's Guidelines for Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (2003), and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Commonwealth University. The surgical and experimental procedures were similar to those described previously for examining the postero-lateral suprasylvian cortex in cat [3].

Surgical procedures

Adult cats (n=3) were anesthetized with sodium pento barbital (40 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and their heads placed in a stereotaxic frame. Under aseptic conditions, a craniotomy was performed to expose the auditory cortex. A stainless steel recording well was secured to the animal's head over the craniotomy to provide access to the FAES during the recording experiment. The scalp was then sutured around the recording well. Routine postoperative care was provided for approximately 7 days, at which time the recording experiment was conducted.

Electrophysiological recording procedures

Recording sessions began by anesthetizing the animal (35 mg/kg ketamine; 2 mg/kg acepromazine, intramuscularly) and securing the implanted recording well to a support bar. This provided head support without obstructing the eyes or ears during sensory testing procedures. The animals were intubated through the mouth and maintained on a ventilator with expired carbon dioxide at approximately 4.5%. Heart rate and body temperature were monitored and a heating pad was used to maintain temperature at approximately 37°C. An intravenous line was placed for continuous administration of fluids and supplemental anesthetics (ketamine 8 mg/kg/h; acepromazine 0.5 mg/kg/h, intravenously), and a muscle relaxant (pancuronium bromide 0.3 mg/kg intravenous initial dose; 0.2 mg/kg/h supplement) was included to prevent spontaneous movements.

For extracellular recording, a glass-insulated tungsten electrode (tip exposure approximately 20 μm and impedance < 1 MΩ) was inserted vertically through the recording well and advanced into the FAES using a hydraulic microdrive. Neurons were studied at regular 125 (or 250)-μm intervals along an electrode penetration. The sensory properties of each isolated neuron were initially determined with a battery of manually presented stimuli: visual cues were moving light or dark bars projected onto a translucent hemisphere (92 cm diameter); auditory cues were clicks, claps, whistles, and hisses. Somatosensory search stimuli included air puffs, brushes, taps to the body surface, as well as compression of deep tissues and joint rotation.

Quantitative evaluation of sensory responses involved the repeated (n=25 each) presentation of computer-triggered visual (‘V’, moving light bar projected on translucent hemisphere using a galvanometer-driven mirror with independent direction, velocity, and amplitude settings) and auditory stimuli (‘A’, free-field, 100 ms duration, white noise, 10-ms shaped rise-fall gates from a hoop-mounted speaker 44 cm from the head), presented alone or in combination (‘VA’). For the combined ‘VA’ conditions, the onset of the visual stimulus preceded the auditory stimulus by 50 ms. The visual stimulus was always presented within its receptive field (or in alignment with other receptive fields in that penetration) and maintained the same stimulus qualities throughout. Auditory stimuli were presented in alignment with the visual stimulus.

Data analysis

For each data file, Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) was discriminated by individual waveshape using templates of the recorded action potentials. For each different waveshape (i.e. single neuron), a peristimulus-time histogram was constructed for each stimulus condition. From the histogram, the response duration was determined and, for that response period, the average spikes per trial and standard deviation were calculated. Neurons that responded independently to separate visual and auditory stimulation were defined as bimodal. Those which showed responses to only one modality, but had that activity significantly influenced (paired t-test; P < 0.05) by the presence of a stimulus from the other modality were defined as subthreshold multisensory neurons. The depth of each neuron within a penetration was noted and correlated with the results of the sensory tests. At the conclusion of each recording penetration, an electrolytic lesion was made to facilitate histological data reconstruction. When recording was completed, the animals received a barbiturate overdose and were perfused intracardially with saline followed by fixation. After stereotaxic blocking, sections (50 μm) were cut in the coronal plane through the recording sites, processed using standard histological procedures and counterstained. A projecting microscope was used to outline sections and reconstruct the recording penetrations.

Results

Of nine attempted recording penetrations (in three animals), five were histologically confirmed to have passed through the FAES (and AEV), as illustrated in Fig. 1. Along these penetrations, a total of 193 neurons were identified. Auditory neurons were the most prevalent (70%, 135 of 193) and occurred in the dorsal (upper) portions of the submerged bank of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus, corresponding to the FAES. Visual neurons (13.5%, 26 of 193) were clustered ventrally (lower), corresponding to the AEV. Within a given penetration, neurons responsive to both auditory and visual stimulation (bimodal; 14.5%, 28 of 193) were generally found between the dorsal auditory cells and the ventral visual units, as previously described [16]. Neurons with other sensory convergence patterns (e.g. visual-somatosensory etc.) were not observed in this sample; unresponsive neurons were infrequent (2%, four of 193). Clusters of ventrally positioned visual units were defined as representing the AEV and were not analyzed further.

Fig. 1.

Location of auditory field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES) and the sensory responses of neurons identified in recording penetrations through it. The lateral view of the cat cortex (top) indicates the location of the FAES (gray area). The vertical lines indicate the location of coronal sections through the FAES depicted at the bottom, upon which the recording penetrations (vertical lines) and the locations of identified neurons (hash-marks) are depicted. Along each penetration, sensory responses were determined at 125 μm intervals and are marked accordingly (A, auditory; V, visual; VA, visual–auditory); each site could represent the responses of more than one identified neuron. In addition, the location of neurons showing subthreshold multisensory responses (black triangle=facilitation; black circle=suppression) are also shown. Although more than one neuron could show subthreshold multisensory effects at a given site, only those in which the effects were different are so indicated. Dashed lines depict the borders with adjoining representations, AEV, anterior ectosylvian visual area.

Within the FAES, essentially the same battery of sensory tests was presented to each neuron (total=133) in each penetration, whereby visual and auditory stimuli were repeatedly presented separately and then in combination. Of the FAES neurons, a total of 22 (22 of 133, 16.5%) responded to both auditory and visual stimulation presented alone (i.e. were bimodal), and showed an increased response when the two stimuli were combined, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. In contrast, even though a wide variety of visual stimulus permutations were presented during the sensory mapping phase, the vast majority of FAES neurons seemed responsive only to auditory stimuli (86 of 133, 65%). Nevertheless, the lack of an overt visual response was not predictive of activity levels when visual and auditory stimuli were combined. Examples are shown in Fig. 2b and c where acoustically driven neurons were unresponsive to visual stimulation alone, but had their auditory responses significantly influenced by the presence of a concurrent visual stimulus. Significant subthreshold multisensory effects were observed in 18 neurons (13 of 133, 13.5%) of which most (13 of 18, 72%) showed facilitation in response to combined auditory–visual stimulation, whereas substantially fewer (five of 18, 28%) exhibited suppression.

Fig. 2.

Responses of field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES) neurons to auditory, visual, and combined auditory–visual stimulation. (a) A traditional bimodal neuron showed a suprathreshold response to auditory (square wave labeled ‘A’) and to visual (ramp labeled ‘V’) stimuli presented alone, and generated a statistically significant enhancement of activation when the same stimuli were combined (square wave and ramp, together, ‘AV’). (b) Another FAES neuron was activated by an auditory stimulus, but not by visual. When the same stimuli were combined (AV), the response to the auditory stimulus was, however, significantly facilitated. (c) A different FAES neuron was activated by an auditory stimulus, but not by visual, and when the same stimuli were combined (AV), the auditory response was significantly suppressed. Sp, spontaneous activity level; error bars=standard deviation; *P value of less than 0.05 paired t-test.

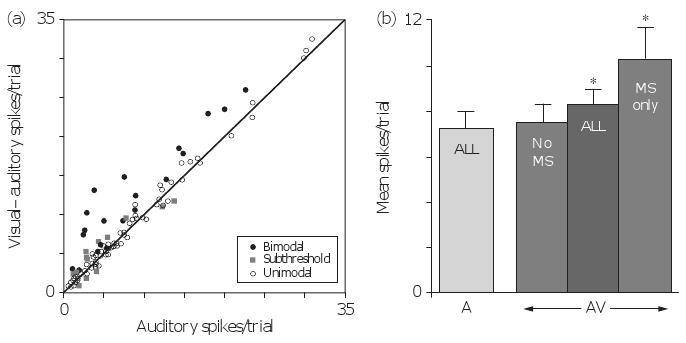

When the populations of both the standard bimodal neurons (22 of 133, 16.5%) and subthreshold multisensory neurons (18 of 133, 13.5%) were summed, it is apparent that 30% of the auditory FAES was influenced by nonauditory inputs. As essentially the same stimuli were used to test each FAES neuron, it was possible to assess the level of activity contributed by each type of neuron to the overall FAES response. When the response to combined stimulation was plotted against that elicited by an auditory stimulus presented alone (Fig. 3a), activity levels of unimodal auditory neurons clustered near the line of unity, whereas that of bimodal neurons generally fell high above the line, and responses of facilitory subthreshold neurons fell between those of the other two response types. Similarly, Fig. 3b shows that the mean response of unimodal auditory neurons to combined visual–auditory stimulation (x=7.5 ± 0.8 SEM spikes/trial) was unchanged from auditory stimulation alone (x=7.3 ± 0.7 SEM). Not surprisingly, when the activity was averaged for only those neurons with significant multisensory effects, the average response to combined visual–auditory stimulation was substantially increased (x=10.3 ± 1.4 SEM). Ultimately, despite the fact that multisensory neurons represent only 30% of the FAES population, the entire sample (unimodal and multisensory neurons together) showed an increased combined response (x=8.4 ± 0.6 SEM spike/trial) that was statistically significant (P < 0.001; paired t-test).

Fig. 3.

Multisensory influences on auditory processing in field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES). (a) The scatter plot shows the relationship, for each FAES neuron, of its responses to auditory (x-axis) versus combined visual–auditory (y-axis) stimulation. Note that for neurons that did not show multisensory properties (open circles), their responses fell on or near the line of unity. Neurons that showed subthreshold multisensory effects (gray squares) fell on the outer edges of the range of unimodal responses, where subtle but significant response changes were observed. Finally, bimodal neurons (black circles) showed the largest response changes and these effects generally fell at levels beyond those achieved by subthreshold facilitation. (b) The bar graph illustrates the average auditory response (7.3 ± 0.7 SEM spikes/trial; light gray bar labeled ‘ALL’) of the entire FAES sample, and this level of activity is compared with the responses elicited by different neuron types to the combined auditory–visual stimulation (AV – dark gray bars). For the population of unimodal FAES neurons, the response to combined auditory visual stimulation (average=7.5 ± 0.8 SEM spikes/trial) was not different from that elicited by the auditory stimulus presented alone. In contrast, it was not surprising that neurons, which showed multisensory (MS) properties (bimodal and subthreshold, labeled ‘MS only’) revealed a significant difference in their averaged responses to combined auditory–visual stimulation (x=10.3 ± 1.4 SEM). Furthermore, multisensory effects significantly influenced the average response of the entire FAES population (x=8.4 ± 0.6 SEM spike/trial; labeled ‘ALL’) to the combined visual–auditory stimulus.

Discussion

In accordance with other reports, the present results show that the FAES is overwhelmingly responsive to auditory stimulation. In addition, when tested for inputs from other sensory modalities, several studies have noted the presence of multisensory neurons (e.g. excited by stimuli from more than one modality; [11,12,16–20]). Those multisensory studies used a paradigm that could, however, identify only the bimodal form of multisensory neuron. Using different search parameters that have been successful in identifying nonbimodal multisensory neurons in other areas [2–4,21], this study revealed that subthreshold forms of multisensory processing also occur in the FAES. These neurons were activated only by an auditory stimulus, but had that response significantly modulated by the presence of a seemingly ineffective visual stimulus. FAES neurons that showed subthreshold multisensory processing represented approximately 13.5% of the present sample, occurred without apparent pattern throughout the region, and either had its auditory response facilitated or suppressed by a concurrent visual cue. These results were quite similar to the subthreshold multisensory effects recently described in visual [3,4,21] and somatosensory [2] cortex. Ultimately, the presence of multiple forms of multisensory neurons in the FAES suggests that its auditory activity can be influenced by nonauditory inputs. This notion was confirmed: the average response of the FAES to an auditory cue was significantly modulated by concurrent visual stimulation.

The present results also indicate that bimodal and subthreshold multisensory neurons do not necessarily exhibit the same range of response, whereas bimodal neurons can show dramatic response increases (e.g. response enhancement, [22]), subthreshold neurons showed lower levels of response change (and unimodal neurons showed no response change at all). Thus, a mixed population of neurons can respond to a given set of cues with a range of integrated activity, with subthreshold multisensory neurons providing an intermediate level of activation between the highly integrative bimodal neurons on one end and nonintegrative functions of unimodal neurons on the other. In contrast, subthreshold multisensory neurons may provide a subtle but important smoothing function for distribution of activity within a neuronal population. Such a possibility would also support the likelihood that multisensory convergence itself occurs across a continuum of patterns extending between bimodal and unimodal forms [4].

Conclusion

Neurons in auditory FAES exhibit both bimodal and subthreshold forms of multisensory convergence and processing. Response levels achieved by these different populations suggest that subthreshold multisensory neurons produce response levels intermediate to those elicited in bimodal or in unimodal neurons. As such, subthreshold multisensory neurons may also represent an intermediate step along a continuum of multisensory convergence patterns from purely unimodal (no convergence) at one end to highly integrative bimodal neurons at the other.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS039460 to M.A.M. B.L.A. was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- 1.Horn G. The effect of somaesthetic and photic stimuli on the activity of units in the striate sortex of unanesthetized, unrestrained cats. J Physiol. 1965;179:263–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dehner LR, Clemo HR, Meredith MA. Cross-modal circuitry between auditory and somatosensory areas of the cat anterior ectosylvian sulcal cortex: a ‘new’ form of multisensory convergence. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:387–401. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allman B, Meredith MA. Multisensory processing in ‘unimodal’ neurons: cross-modal subthreshold auditory effects in cat extrastriate visual cortex. J Neuorphysiol. 2007;98:545–549. doi: 10.1152/jn.00173.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allman BL, Bittencourt-Navarrete RE, Keniston LP, Medina A, Wang MY, Meredith MA. Do cross-modal projections always result in multisensory integration? Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2066–2076. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizley JK, Nodal FR, Bajo VM, Nelken I, King AJ. Physiological and anatomical evidence for multisensory interactions in auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2172–2189. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugihara T, Diltz MD, Averbeck BB, Romanski LM. Integration of auditory and visual communication information in the primate ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11138–11147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3550-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarey JC, Irvine DRF. Auditory response properties of neurons in the anterior ectosylvian sulcus of the cat. Brain Res. 1986;386:12–19. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middlebrooks JC, Clock AE, Xu L, Green DM. A panoramic code for sound location by cortical neurons. Science. 1994;264:842–844. doi: 10.1126/science.8171339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Las L, Ayelete-Hashahar S, Nelken I. Functional gradients of auditory sensitivity along the anterior ectosylvian sulcus of the cat. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3657–3667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4539-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malhotra S, Hall AJ, Lomber SG. Cortical control of sound localization in the cat: unilateral cooling deactivation of 19 cerebral areas. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1625–1643. doi: 10.1152/jn.01205.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meredith MA, Clemo HR. Auditory cortical projection from the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (AES) to the superior colliculus in the cat: an anatomical and electrophysiological study. J Comp Neurol. 1989;289:687–707. doi: 10.1002/cne.902890412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace MT, Meredith MA, Stein BE. Converging influencing from visual, auditory, and somatosensory cortices onto output neurons of the superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1797–1809. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang W, Wallace MT, Jiang H, Vaughan W, Stein BE. Two cortical areas mediate multisensory integration in superior colliculus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:506–522. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemo HR, Stein BE. Organization of a fourth somatosensory area of cortex in cat. J Neurophysiol. 1983;50:910–925. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mucke L, Norita M, Benedek G, Creutzfeldt O. Physiologic and anatomic investigation of a visual cortical area situated in the ventral bank of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1982;46:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00238092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meredith MA. Cortico-cortical connectivity and the architecture of cross-modal circuits. In: Spence C, Calvert G, Stein B, editors. Handbook of multisensory processes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace MT, Meredith MA, Stein BE. Integration of multiple sensory modalities in cat cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1992;91:484–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00227844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korte M, Rauschecker JP. Auditory spatial tuning of cortical neurons is sharpened in cats with early blindness. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1717–1721. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang H, Lepore F, Ptito M, Guillemont JP. Sensory modality distribution in the anterior ectosylvian cortex of cats. Exp Brain Res. 1994;97:404–414. doi: 10.1007/BF00241534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Lepore F, Ptito M, Guillemont JP. Sensory interactions in the anterior ectosylvian cortex of cats. Exp Brain Res. 1994;101:385–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00227332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allman BL, Keniston LP, Meredith MA. Subthreshold auditory inputs to extrastriate visual neurons are responsive to parametric changes in stimulus quality: sensory-specific versus non-specific coding. Brain Res. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.086. PMID: 18479671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meredith MA, Stein BE. Visual, auditory, and somatosensory convergence on cells in the superior colliculus results in multisensory integration. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:640–662. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]