Abstract

Alteration in gene copy number provides a simple way to change expression levels and alter phenotype. This was fully appreciated by bacteriologists more than 25 years ago, but the extent and implications of copy number polymorphism (CNP) have only recently become apparent in other organisms. New methods demonstrate the ubiquity of CNPs in eukaryotes and their medical importance in humans. CNP is also widespread in the Plasmodium falciparum genome and has an important and underappreciated role in determining phenotype. In this review, we summarize the distribution of CNP, its evolutionary dynamics within populations, its functional importance and its mode of evolution.

Copy number polymorphism

Two people can do more work than one. The same rationale applies to genes. Increasing gene copy number (CN) provides a simple way to increase gene expression without requiring a change in sequence. A flood of studies over the past five years have demonstrated that copy number polymorphism (CNP) is ubiquitous in eukaryotic genomes, explains a notable proportion (~17%) of expression variation and accounts for much of the genomic difference among individuals [1–4]. This revolution in our understanding of genetic variation has been driven by new technologies, such as microarrays, that enable direct assessment of CNP at a genome-wide scale. These methods reveal that CNP underlies many human pathologies and is involved in adaptive evolution in some cases [5,6]. As a consequence, there has been a shift in how biologists think about genetic variation. Although most genetic and phenotypic variation was assumed ten years ago to be due to point mutations, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and CNP are now considered on a more equal footing [2].

Work on CNP in malaria parasites started in the 1980s, but then went strangely silent. The importance of CN was first appreciated with the discovery that a candidate drug-resistance gene, Plasmodium falciparum multidrug-resistance 1 gene (pfmdr1), showed elevated CN in Southeast Asian parasites and was associated with elevated resistance to a variety of antimalarial drugs [7]. Elegant laboratory experiments showed that chromosome 5 could be expanded and contracted by selection with mefloquine and chloroquine [8]. Similarly, deletions on chromosome 2 and 9 were shown to be associated with cell cytoadherence [9,10]. At the same time, pulsed-field gels revealed that malaria parasite chromosomes are extremely polymorphic in size, suggesting large-scale structural rearrangements [11]. Strangely, interest in this topic waned for two decades, probably reflecting the constraints of available technology. Before real-time PCR and microarrays, determining CN was challenging. By contrast, working with sequences was relatively easy. Malaria biologists shared the expectations of those working on other organisms that sequence data alone would explain most phenotypic variation.

The aims of this review are to summarize our current understanding of CNP in malaria parasites, highlight research that has driven this field forward and stimulate future work on this topic. Here, we (i) summarize the genomic distribution of CNP in P. falciparum, (ii) ask whether CNP influences parasite phenotype, (iii) describe what is known about the genetics and population genetics of CNP, (iv) discuss the implications of CNP for genome-wide association studies and (v) highlight questions about CNP of particular interest for Plasmodium. CNP is an emerging field in parasite genetics, so our aim is to raise questions rather than to provide answers.

Distribution of CNP in Plasmodium falciparum

Methods for detecting CNP are based on comparing relative amounts of DNA present in different parts of the genome. For example, early studies examined the strength of hybridization of pfmdr1 relative to a gene that was assumed to have a single copy in the P. falciparum genome [12]. Current methods follow the same principle, but the scale and precision of the data generated greatly simplify such studies. Real-time PCR is the method of choice for determining CN when a small number of genes are examined in large numbers of samples. However, microarray approaches or next-generation sequencing provide a more cost-effective solution for genome-wide evaluation of CN (Box 1).

Box 1. Methods for CNP detection

Comparative genomic hybridization

Gnomic DNA from two parasite lines is labeled with either Cy3 or Cy5 fluorophore dyes and equal quantities are hybridized to the microarray (two-color hybridization), consisting of unique oligonucleotide probes representing the 3D7 reference genome. Hybridization of a single parasite line (single-color hybridization) is also used on some platforms (Affymetrix). When there is no variation in sequence and/or CN, the two different samples hybridize equally and the log2 ratio of the signals from the two dyes is near zero. If a tandem duplication is present in sample A (red dye), the signal from the probes in the duplicated region will be approximately twice that of sample B (green dye) (log2 ratio = ~1) (Figure I). Similarly, a deletion in sample B would cause a displacement towards the red dye; however, the ratio would be much stronger (log2 ratio >4). In practice, CN reduction and deletion might be difficult to distinguish. Similarly, highly polymorphic genes might hybridize poorly and can be confused with deletions. An alternative analysis approach does not require a reference genome and relies on calculating average or median values for blocks of probes.

Comparative genomic hybridization software

A variety of algorithms are available for analyzing CNP from microarray data, implemented in software such as NimbleScan and Nexus Copy Number 3.0 software (BioDiscovery, Inc.; El Segundo, California). When genomic DNA is limiting, whole genome amplified material can also be used with minimal loss of resolution [39].

Microarray platforms

Microarrays were originally printed on glass slides. Chip-based synthesis of oligo probes provides better quality control, and companies such as Affymetrix and Nimblegen-Roche use different synthesis strategies to generate high-density microarrays containing millions of features. An attractive feature of Nimblegen-Roche and Agilent arrays is that single custom arrays can be ordered, tested and redesigned iteratively, giving researchers control over the design process. The high density of Affymetrix chips (>6 million probes) provides advantages for some applications (Table I).

Next-generation sequencing

Short-read sequencing on platforms such as the Illumina Genome Analyzer has many potential advantages for CNP detection and could replace microarrays as the method of choice. In this case, CN can be inferred from read depth comparisons, rather than hybridization. Paired-end reads enable identification of chromosome breakpoints and determination of the orientation and position of gene copies in the genome [62,63]. Furthermore, deletions can be distinguished from highly polymorphic genes and additional DNA can be detected that is not present in the reference sequence. Finally, SNPs can be directly sequenced on the same platform, rather than indirectly inferred from hybridization.

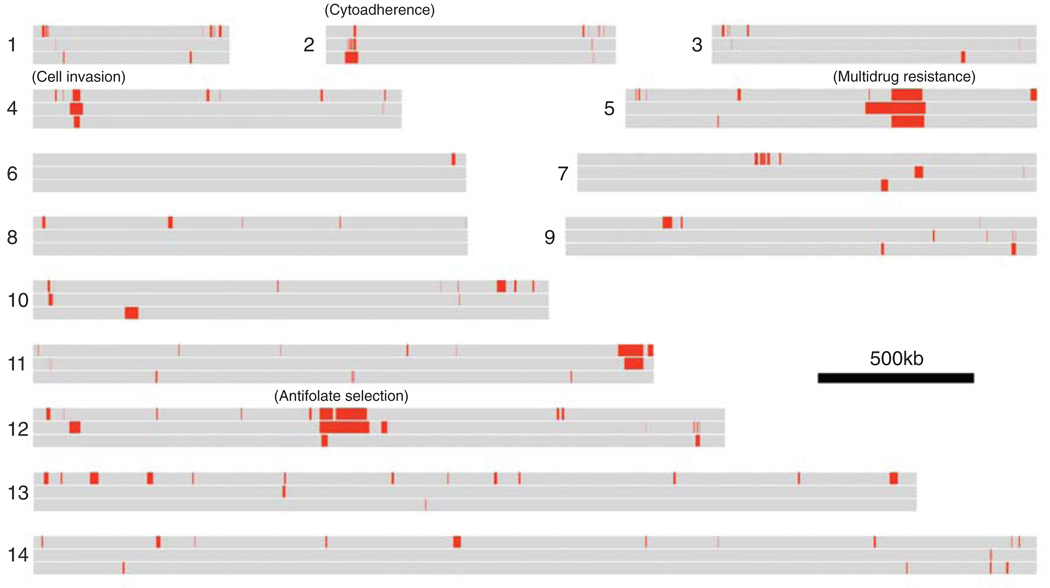

Three microarray surveys represent our current understanding of the distribution of CNP in Plasmodium. Kidgell et al. [13] used an Affymetrix array containing 298 752 25-mer oligos to examine CNP in 14 single-clone parasites from four continents. Ribacke et al. [14] used glass slides printed with 6850 70-mer oligos to examine nine parasite isolates. Jiang et al. [15] used an Affymetrix array containing 2.56 million 25-mer probes (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/P_falciparum/news.shtml) tiled across the genome to examine four parasite isolates. The data from these studies [13–15] were collected on different microarrays using different parasite isolates and differing statistical criteria. Nevertheless, they provide a qualitative overview of CNP in P. falciparum (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of CNP in Plasmodium falciparum. The horizontal gray bars represent the 14 chromosomes. Each chromosome is divided into three sections – top section, Jiang et al. [15]; middle section, Kidgell et al. [13]; bottom section, Ribacke et al. [14]. The red sections show regions where CNP (either loss or gain relative to the reference genome) was detected in each of the three studies. Phenotypes that are (or are suspected to be) associated with CNP are marked on the map. Note that different samples were analyzed in each study and, hence, although many common CNPs are observed, the patterns seen are not expected to be identical.

In general, there is good agreement between the studies. For example, Jiang et al. [15] identified 181 amplified genes, of which 74 (41%) had been reported previously [13,14]. Kidgell et al. [13] described an average of 20.5 genes (range 1–63) different in CN between isolates, equivalent to 72 kb (range 0.8–251 kb), whereas Ribacke et al. [14] found that 29 genes (range 6–54) differ between parasites, equivalent to 130 kb (34–282 kb). The data are broadly consistent and suggest that 0.3–1.0% of the genome differ in CN between parasites. These data correspond well to patterns of CNP in the human genome: McCarroll et al. [16] found that, on average, 5.9 Mb or 0.2% of the ~3000 Mb genome differed in CN among individuals.

Most of the parasites examined in these three studies had been adapted to long-term culture. One concern is that the CNPs observed might have originated in the laboratory and were not representative of naturally occurring parasites. The two Ugandan field samples included in Ribacke et al. [14] study show limited CNP, although further data is required to determine whether these are representative.

In addition to CNPs on chromosome 5 and 12 (see below), numerous other CNPs with potential impact on parasite phenotype were observed. All three studies identified a CNP on chromosome 4 containing pfRH1 (PFD0110w), a reticulocyte-binding-like protein. Amplification of this locus is correlated with overexpression and mediates sialic-acid-dependent invasion of erythrocytes [17]. Intriguingly, the two parasites with high CN in the dataset of Ribacke et al. [15] also show the highest growth rates in culture, consistent with a functional relationship. CNPs containing genes that potentially influence other phenotypes (including sexual differentiation, cell-cycle regulation and metabolism) are also observed, providing new targets for functional studies.

Does CNP influence phenotypic variation?

Transcriptional variation

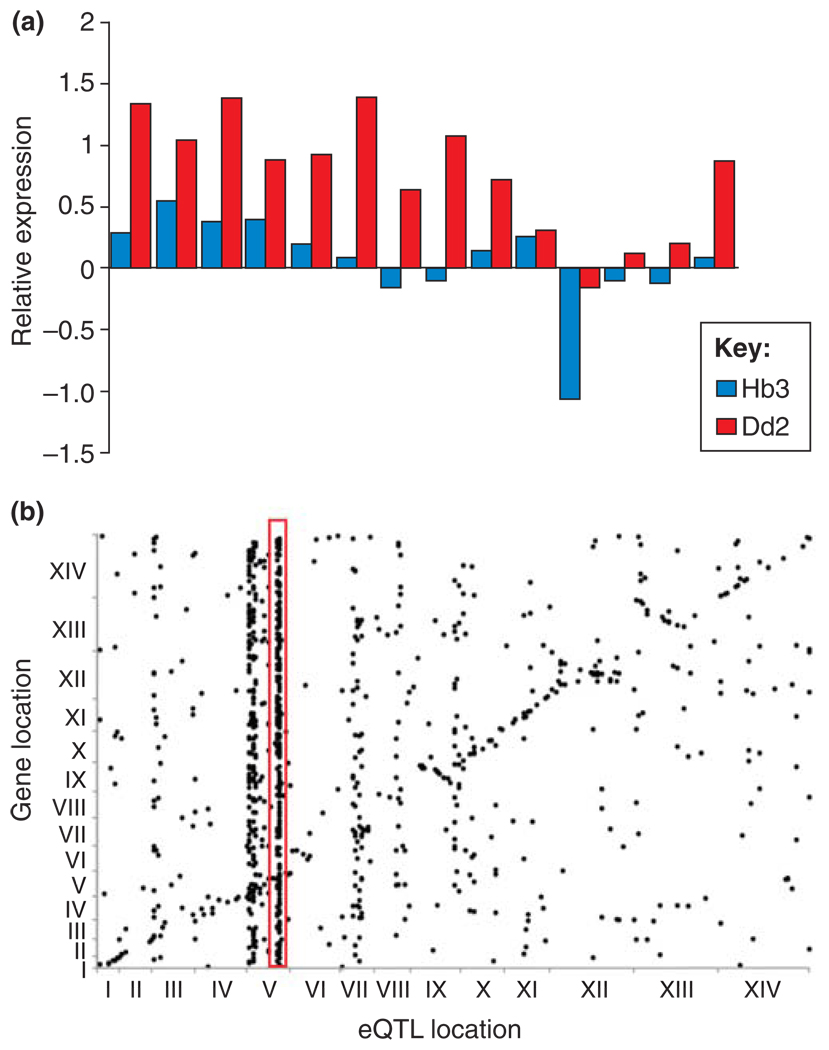

Because CNP alters gene dosage, we might expect it to alter levels of gene expression. This is clearly the case for genes in the chromosome 12 amplicon that segregates in the genetic cross. Progeny inheriting multiple copies of this amplicon from a multidrug-resistant parent (Dd2) express these genes at higher levels than progeny inheriting a single copy from the drug-sensitive (Hb3) parent at all 14 genes [18] (Figure 2a). Similarly, expression scales with CN in samples carrying different CNPs at the GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 (gch1) locus [19]. More surprisingly, the chromosome 5 amplicon results in upregulation of multiple genes elsewhere in the parasite genome (Figure 2b). Gonzalez et al. [18] examined quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for expression variation in the progeny of the Dd2 × Hb3 genetic cross. The most prominent trans-regulatory locus, influencing 269 transcripts, coincides with the chromosome 5 amplification event carrying pfmdr1 and 13 other genes. 85% of transcripts (228/269) were upregulated in the Dd2 parent (or progeny) carrying the Dd2 alleles at these loci. These data demonstrate how drug selection on the Dd2 parental clone led not only to a CN change in the pfmdr1 gene but also to increased copies of putative neighboring regulatory factors that fundamentally alter this parasite’s transcriptional network.

Figure 2.

CNP and expression variation. (a) Cis regulation. The bar chart compares levels of expression (relative to 3D7) in the progeny of the HB3 × Dd2 genetic cross for 14 genes on chromosome 5. Mean expression levels in progeny inheriting this region of chromosome 5 from Dd2 and carrying multiple copies of these genes are compared with expression levels of progeny carrying a single copy of these genes inherited from Hb3. In all 14 genes, expression level is higher in progeny carrying multiple copies of these genes inherited from Dd2. These data demonstrate a strong impact of CN on local (cis) expression variation. (b) Trans regulation. The dot plot summarizes results of a linkage analysis designed to identify genome regions controlling expression phenotypes in the HB3 × Dd2 genetic cross. The genomic position of each gene for which expression was quantified is shown on the y-axis, and the genome position of the QTLs controlling expression at each gene is shown on the x-axis. The dots forming a diagonal line show genes that are under local (cis) control. However, some QTLs control expression of multiple genes in the genome. These are evident as vertical stacks of dots. The red box highlights the strong trans-regulatory QTL on chromosome 5 that co-localizes with the pfmdr1 amplicon. These data demonstrate how one CNP can dramatically alter genome-wide expression profiles. Redrawn, with permission, from data reported in Ref. [18].

Fitness costs of CNP

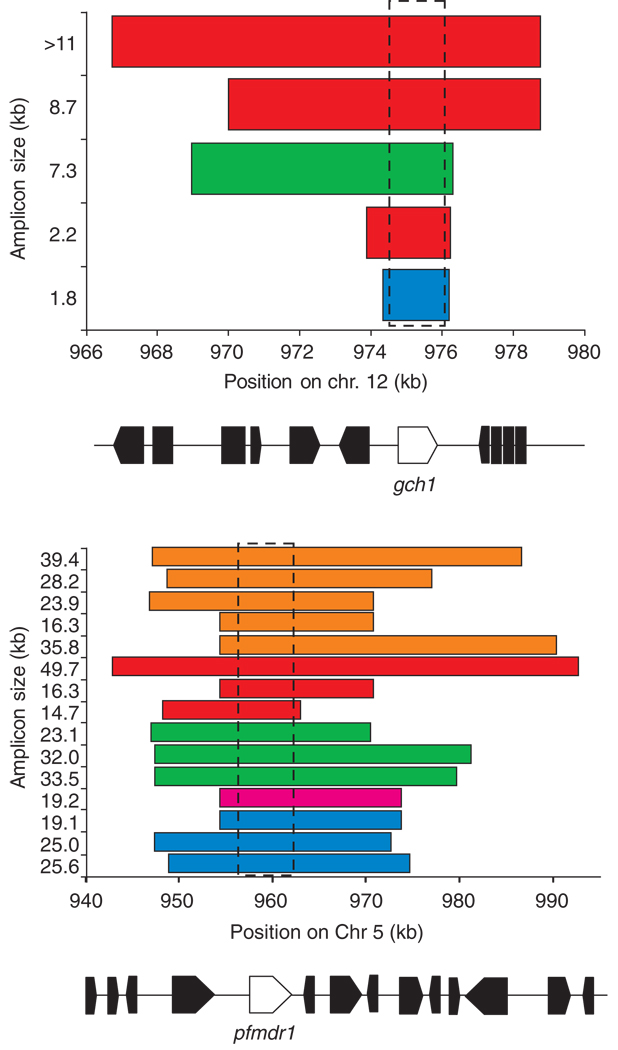

Direct evidence for fitness costs of CNP comes from laboratory competition experiments: two mefloquine selected clones carrying elevated pfmdr1 CN showed multiplication rates that were 6–9% lower than the sensitive clone from which they were derived, in the absence of selection [20]. Indirect evidence of fitness costs comes from work on the population genetics of CNP. Although large regions spanning >100 kb of chromosome 5 containing pfmdr1 were initially observed to be amplified in Southeast Asia [21], recent studies have revealed that the amplicons present are considerably smaller, ranging from 15 to 49 kb [22] with the predominant amplicon type measuring 16 kb. These data suggest that either amplified regions have been reduced in size or newly arisen CNPs with small amplicons have outcompeted large deleterious amplicons. At the gch1 on chromosome 12, parasites bearing amplicons measuring >11, 8.7 and 2.3 kb have the same genetic background, suggesting that progressive streamlining of amplicons has been operating [19]. In this example, minimal amplicons containing only the gch1 locus predominate in Thailand, which is consistent with strong selection for small amplicons.

CNP and drug treatment

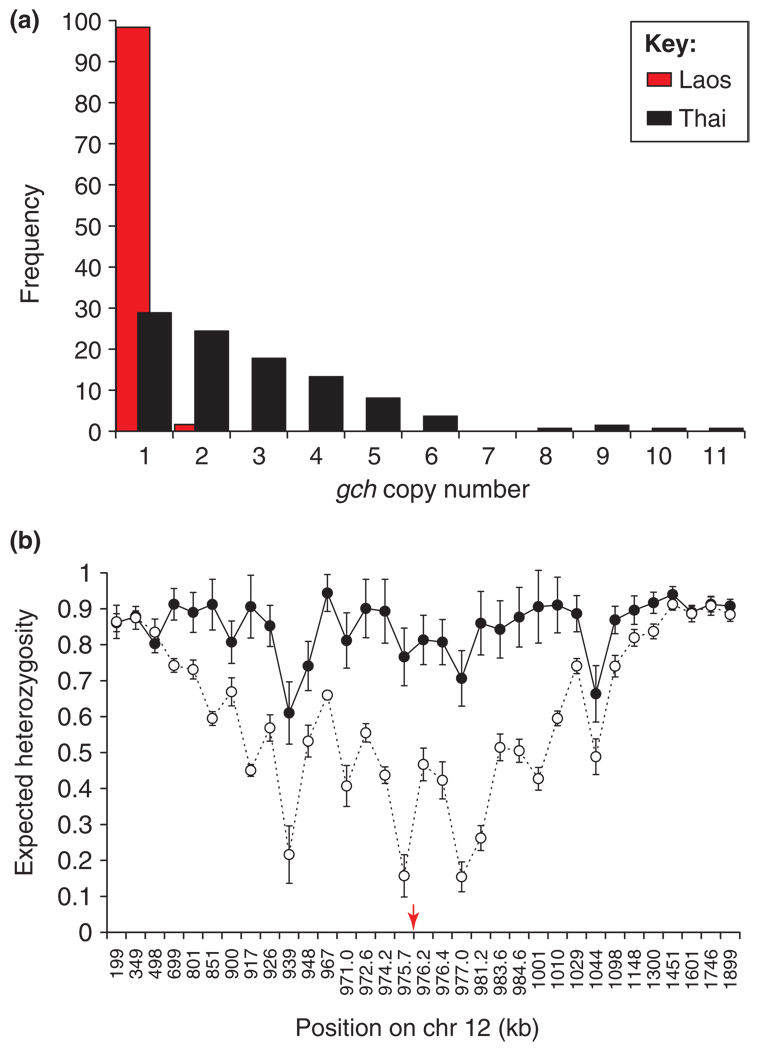

CNPs that are under positive selection are of particular interest because they play an important part in parasite survival and adaptation. We can utilize patterns of genetic variation to provide an indirect approach to identify CNPs that are under positive selection and, therefore, have a functional role in parasite biology. To illustrate this approach, we summarize work on CN variation at the gch1 gene on chromosome 12. This gene encodes an enzyme that is the first step in the folate biosynthesis pathway. Enzymes downstream in this pathway are targeted by the antifolate compounds sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine. Kidgell et al. [13] first described this CNP and speculated that increased CN at the gch1 could be selected either directly or indirectly by treatment with antifolate drugs. Patterns of genetic variation in natural parasite populations strongly support these conclusions (Figure 3). Nair et al. [19] compared gch1 CNPs in parasites from Thailand (strong historical antifolate selection) with those from neighboring Laos (weak antifolate selection). Although 72% carried multiple (2–11) copies in Thailand, just 2% of chromosomes had amplified CNs in Laos. The high level of geographical differentiation exceeded that observed at 73 synonymous SNPs, strongly suggesting the action of selection. Furthermore, microsatellite variation was reduced and linkage disequilibrium (LD) increased in a 900-kb region flanking gch1 in parasites from Thailand, consistent with rapid recent spread of chromosomes carrying multiple copies of gch1. Two other features of the data also strongly suggest natural selection. There were five amplicon types containing 1 to >6 genes and spanning 1–11 kb. These were found on three different genetic backgrounds, consistent with parallel evolution of this CNP. Finally, parasites bearing dhfr-164L, which causes high-level resistance to antifolate drugs, carry significantly (P = 0.00003) higher CN of gch1 than parasites bearing 164I do, indicating functional association between genes located on different chromosomes but linked in the same biochemical pathway. It is still unclear whether direct selection by antifolate drugs or indirect compensation for mutations elsewhere in the parasite genome is the selective force driving CN change.

Figure 3.

Adaptive evolution of CNP containing GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 (gch1). Patterns of genetic variation at this locus strongly suggest that it has been under strong recent selection. (a) Geographical differentiation. The bar chart shows the frequency of amplification in two neighboring countries in Southeast Asia. In comparison, SNPs show similar allele frequencies between these two locations [19,61]. (b) Genetic hitchhiking. Plot of genetic variation (y-axis), measured by expected heterozygosity (the probability of randomly drawing two different alleles) across chromosome 12 (x-axis). Genetic variation is reduced in Thailand (open circles, dotted lines) relative to Laos (closed circles, solid lines), suggesting that strong recent selection has driven the spread of chromosomes carrying multiple copies of gch1. Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. [19].

For pfmdr1 (chromosome 5), there is direct evidence that CNP is driven by drug pressure. Field surveys show strong associations between high CN and increased drug resistance to mefloquine, quinine and artemisinin, and lower resistance to chloroquine [23,24]. These data are consistent with selection experiments in which CNP is amplified under mefloquine selection and de-amplified under chloroquine selection [8,25]. Finally, elegant transfection experiments demonstrate that reduction of CN results in higher resistance to chloroquine and lower resistance to mefloquine, halofantrine and artemisinin [26,27]. Recently, CNP has been demonstrated in the Plasmodium vivax homologue pvmdr1, where it is also associated with multidrug resistance [28,29]. Interestingly, CNP involving pcmdr1 underlies mefloquine resistance in the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi, but gene copies in this case are found on different chromosomes, rather than arranged in tandem [30].

Other CNPs might also be involved in drug resistance. In laboratory drug-selection experiments, Jiang et al. [31] observed deletions of 15 genes on chromosome 10 that might contain loci involved in adaptation to drug treatment. Dharia et al. [32] generated parasite clones resistant to fosmodomycin, an inhibitor of isoprenoid synthesis. Two independently derived genetic mutants showed approximately threefold amplification of the ~100kb region containing 23 genes, including the gene encoding the enzyme targeted by this drug. Similarly, parasites showing 200-fold resistance to cysteine protease inhibitors have been selected in the laboratory; these parasites showed five- to sixfold amplification of a chromosome 11 region containing falcipain-2 and -3 [33]. Up to 44-fold amplification of genome regions on chromosome 4 containing dhfr have been observed in two drug-selection experiments [34,35]. In nature, specific SNPs confer pyrimethamine resistance, although few field surveys have examined CNP at this locus. One possibility is that CNP is a transient response to selection at this locus and that mutation in one of the copies subsequently enables deamplification. An attractive feature of this model is that amplification raises the mutation rate at the amplified locus. Similar amplification–mutation–deamplification models [36,37] might explain the claims of ‘directed’ mutation in bacterial systems.

CNP and culture adaptation

Culture adaptation results in genetic changes in the parasite genome, just as domestication alters the genomes of crops and farm animals. There have been no systematic attempts to understand genome-wide changes occurring during culture adaptation, but the available data suggest that substantial CN change occurs. Subtelomeric deletions on chromosome 2 and 9 repeatedly arise during culture adaptation. The chromosome 2 deletion includes the knob-associated histone-rich protein gene and is associated with loss of cytoadherence [9], whereas the chromosome 9 event involves loss of erythrocyte membrane proteins genes and influences both cytoadherence and gametocytogenesis [10,38]. These deletions are evident in the microarray surveys [13,14,39] and sound a caution that studies of population genetics of CN should use material directly from patients to avoid spurious results associated with laboratory adaptation. Microarray analyses of clones derived from parasite clone P1B5 enable fine mapping of the functional genes [39]. Deletions on chromosome 9 containing three genes and associated with gametocytogenesis have been previously described [38,40,41]. In the gametocytogenesis-defective clones analyzed by Carret et al. [39], only the breakpoint open reading frame gene is deleted, which narrows the range of candidate loci for this phenotype.

Genetics and population genetics of CNP

Rate of CNP mutation

In mammals, CNPs have high mutation rates. Estimates range from 1.1 × 10−2 to 3.6 × 10−3 per generation in inbred mice lineages [42], 2 × 10−4 per generation in human Y chromosomes [43] and 10−4 per generation for genetic disorders involving structural change [44]. These estimates are up to 5–7 orders of magnitude higher than estimates of the SNP mutation rate (~10−9) [45]. Measurement of asexual mutation rate for Plasmodium CNP could be achieved using mutation accumulation lines [46] or by examining the rate of evolution of particular CNPs underlying drug resistance in selection experiments. Using the second approach, Preechapornkul et al. [20] estimated that pfmdr1 duplications arise once in 108 parasites during laboratory selection experiments and amplification from two to three copies occurred in one in 1000 parasites. Similarly, Jiang et al. [31] examined genome-wide changes in CNP arising during selection of laboratory cultures. They found deletions of 15 genes on chromosome 10 and amplification of chromosome 5 regions containing pfmdr1 during drug-selection experiments. Each experiment involved ~5 × 108 parasites, so the upper limit for the mutation rate is 2 × 10−9.

Mechanisms of CN mutation

Chromosome breakage sites for the pfmdr1 amplicon (chr 5) and the gch1 amplicons (chromosome 12) commonly contain long monomeric A/T tracts or microsatellite repeat sequences [19,22,47]. In the case of the pfmdr1 amplicon, the sites involved in breakage have longer arrays of A/T monomers than elsewhere in the genome, suggesting that such sites are prone to chromosome breakage. These data parallel findings from Drosophila [48] and other organisms [49] and support a mechanism of slip-strand mispairing during DNA replication. It is not clear whether CNP arises in nature during asexual mitotic replication in blood-stage parasites or during meiosis after gamete fusion in the mosquito midgut. The fact that CNP has been documented during culture adaptation and in numerous selection experiments clearly demonstrates that CN mutation can occur during asexual growth. Analysis of CNPs occurring in laboratory crosses should also be possible and will reveal whether meiotic division is also an important source of CNPs. The dynamics of CNPs within individual infections are also poorly understood. Analyses of CNP by microarray of real-time PCR methods examine populations of parasites and provide estimates of the average CN at any locus. In reality, if asexual mutation rate is high, we might expect parasites within the bloodstream to show a spectrum of CNP at any particular locus. Cloning of parasites from single infections or direct visualization of CN on individual chromosomes by methods such as fiber fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [50] could aid understanding of the dynamics of CNP within infections.

Complexity of CNP evolution

SNP mutation is generally considered to be unidirectional, with a very low probability of reversion to the ancestral state. By contrast, CN is expected to both increase and decrease, and reversion to single-copy state can occur. Reversion to single-copy state provides the simplest explanation for patterns of variation observed around well-studied CNPs on chromosomes 5 and 12 [19,22]. In both cases, microsatellite haplotypes flanking tandemly repeated amplicons are also commonly found on chromosomes with single-copy status. In these two examples, there is clear evidence for multiple independent origins of amplification. In the case of pfmdr1, 15 different amplicon types are observed in parasites sampled from a single clinic, and these fall into five groups based on flanking microsatellite markers [22] (Figure 4). Hence, there are between 5 and 15 independent origins of CN amplification. In the case of gch1, five different amplicons with at least three different flanking haplotypes were found, consistent with a minimum of three amplification events [19]. An important point is that amplicons of different size might have the same origin and amplicons of the same size might have different origins. Therefore, amplicon size data should be treated with caution when investigating the number of independent origins of a particular CNP [47]. Similar complex patterns of recurrent amplification have been observed in both bacteria and inbred mouse lineages [42,51].

Figure 4.

Complex evolution of CNP in P. falciparum. Bar plots show the different amplicons observed on (a) chromosome 12 and (b) chromosome 5 in parasites sampled from a single clinic on the Thailand---Burma border. The x-axis shows the span of each amplicon, and the size of each amplicon (kb) is shown on the y-axis. Gene maps of the region are shown beneath the x-axis, with gch1 and pfmdr1 shown in white and flanking genes shown in black. The amplicons are shown in different colors to show whether they have similar flanking microsatellite haplotypes, suggesting a common origin. The positions of pfmdr1 and gch1 are marked by boxes. We observed strong evidence for parallel evolution of CN amplification in both cases, as well as evidence that amplicons of different sizes share the same origins. The figure also illustrates how characterization of amplicons can effectively identify genes underlying particular phenotypes. In both cases, amplicon boundaries define a single gene --- pfmdr1 on chr 5 and gch1 on chr 12 --- that underlie adaptation to drug treatment. Adapted, with permission, from Refs [19,22].

CNP and genome-wide association mapping

There is currently considerable interest in mapping genes underlying important phenotypic traits such as virulence and drug resistance [52]. Following the model of human association mapping, dense SNP maps are being constructed by resequencing parasites from different geographical regions [53,54]. There are several concerns about the efficiency of using SNP maps to detect phenotypic variation resulting from CNPs [1]. First, genome regions containing CNPs might be underrepresented on SNP maps because SNPs in these regions can show unusual segregation. For example, if a SNP differs in state on two different copies of an amplicon, the SNP will appear heterozygous and will not be assayed. Similarly, SNPs occurring in genome regions containing polymorphic deletions will be inconsistently scored and will be removed from genotyping panels. Second, CNPs might show weak linkage disequilibrium with flanking SNPs [55]. This can result from the rapid mutation of CNP and from frequent reversion to single-copy status. Furthermore, phenotypes determined by CNP might show multiple evolutionary origins, once again reducing the power to detect association with flanking SNPs. The extent to which SNPs can tag CNP is not known. However, the ease with which CNP can be directly determined suggests that optimal strategies for locating underlying phenotypic variation in malaria parasites should involve measurement of both CN and SNP variation, rather than reliance on LD with flanking SNPs. Fortunately, the same microarray platforms can be used to document both SNP and CNP variation [13,16,56]. A strong argument for direct genotyping of CN mutations, rather than reliance on linkage disequilibrium with flanking SNPs, stems from the fact that comparative genomic hybridization (cGH) studies can rapidly identify genes that might be functional. The example of gch1 illustrates this point. Kidgell et al. [13] observed extensive amplification around this locus and were intrigued because this locus encodes the first enzyme in the folate pathway. Subsequent work has shown strong evidence that this locus is under selection, most likely as a consequence of treatment with antifolate drugs [19]. Hence, cGH on a limited number of isolates enabled rapid identification of a CNP that has been selected by drug treatment.

Future prospects

We predict that CNP will be found to underlie a number of important phenotypes in malaria parasites in coming years. An exciting possibility is that complex phenotypes such as virulence might result from a constellation of highly mutable CNP changes, as envisaged for some complex diseases in humans [57]. Understanding the functional role of CNP will require development of efficient methods for manipulation of CN experimentally. Inserting additional gene copies using ‘piggyback’ vectors [58] is one possible approach, although overexpression of single genes using strong promoters, such as such as hrp3 or hsp86, could be used to mimic dosage effects of gene amplification [48]. The availability of genome sequences for parasites infecting rodents and primates will enable CNP studies to be extended to multiple malaria parasite species, improving understanding of CNP evolution [59,60]. In particular, further information is required on the organization of CNP within the genome. CNP is enriched in regions of segmental duplications in mammalian genomes: it will be of interest to see whether similar patterns are observed in Plasmodium. Next-generation sequencing methods, in combination with older methods such as FISH and pulsed-gel electrophoresis, should complement microarray approaches by revealing whether CNPs are arranged as tandem or inverted repeats or translocated to different sites in the genome. We expect that future studies of CNP in Plasmodium will prove to be both biologically interesting and biomedically important.

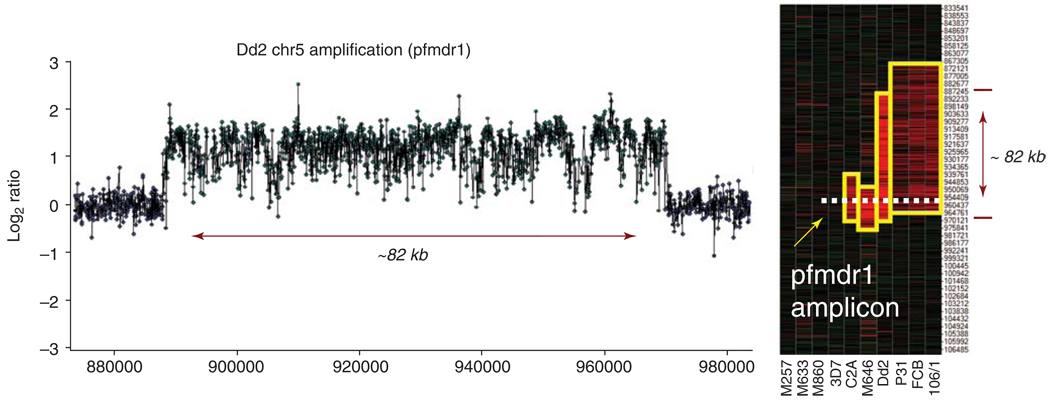

Figure I.

Visualizing comparative genomic hybridization data from microarrays. (a) log2 ratio (Dd2/HB3) plot for chr 5 shows a CNP in Dd2 (log2 ratio = 1.33±0.01) spanning ~82kb and including pfmdr1. (b) Signal intensities for ten isolates represented as a heatmap. The y-axis gives the position (bp) of cGH probes on chr 5. Yellow boxes highlight variable amplicon sizes. Illustrative data generated using Nimblegen-Roche microarrays.

Table I.

Qualitative assessment of different microarray platforms

| Technology | Variable length oligos | Design flexibility | High density |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium masking (Affymetrix) | − | − | +++ |

| Inkjet (Agilent) | − | +++ | + |

| Long oligos (Robotic printer) | + | ++ | − |

| CGH-MP (NimbleGen-Roche) | +++ | +++ | ++a |

One million feature arrays now available. The plus signs provide a qualitative assessment of the design features of these four microarray platforms.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by NIH R01 AI075145 and AI48071 (T.J.C.A.) and AI055035 (M.T.F.). We thank John and Asako Tan and Shalini Nair for comments and assistance in preparing figures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cooper GM, et al. Mutational and selective effects on copy-number variants in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:S22–S29. doi: 10.1038/ng2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estivill X, Armengol L. Copy number variants and common disorders: filling the gaps and exploring complexity in genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1787–1799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman JL, et al. Copy number variation: new insights in genome diversity. Genome Res. 2006;16:949–961. doi: 10.1101/gr.3677206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarroll SA, Altshuler DM. Copy-number variation and association studies of human disease. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:S37–S42. doi: 10.1038/ng2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez E, et al. The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility. Science. 2005;307:1434–1440. doi: 10.1126/science.1101160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry GH, et al. Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1256–1260. doi: 10.1038/ng2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson CM, et al. Amplification of a gene related to mammalian mdr genes in drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1989;244:1184–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.2658061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes DA, et al. Selection for high-level chloroquine resistance results in deamplification of the pfmdr1 gene and increased sensitivity to mefloquine in Plasmodium falciparum. EMBO J. 1992;11:3067–3075. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biggs BA, et al. Subtelomeric chromosome deletions in field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum and their relationship to loss of cytoadherence in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:2428–2432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp DJ, et al. A chromosome 9 deletion in Plasmodium falciparum results in loss of cytoadherence. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87 Suppl 3:85–89. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761992000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemp DJ, et al. Size variation in chromosomes from independent cultured isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 1985;315:347–350. doi: 10.1038/315347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foote SJ, et al. Amplification of the multidrug resistance gene in some chloroquine-resistant isolates of P. falciparum. Cell. 1989;57:921–930. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidgell C, et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribacke U, et al. Genome wide gene amplifications and deletions in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;155:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang H, et al. Detection of genome-wide polymorphisms in the AT-rich Plasmodium falciparum genome using a high-density microarray. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:398. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarroll SA, et al. Integrated detection and population-genetic analysis of SNPs and copy number variation. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ng.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triglia T, et al. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 is required for sialic acid-dependent invasion into human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:162–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales JM, et al. Regulatory hotspots in the malaria parasite genome dictate transcriptional variation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair S, et al. Adaptive copy number evolution in malaria parasites. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preechapornkul P, et al. Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 amplification, mefloquine resistance, and parasite fitness. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1509–1515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00241-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaiyaroj SC, et al. Analysis of mefloquine resistance and amplification of pfmdr1 in multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:780–783. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair S, et al. Recurrent gene amplification and soft selective sweeps during evolution of multidrug resistance in malaria parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:562–573. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price RN, et al. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364:438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson CM, et al. Amplification of pfmdr 1 associated with mefloquine and halofantrine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Thailand. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1993;57:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90252-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowman AF, et al. Selection for mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is linked to amplification of the pfmdr1 gene and cross-resistance to halofantrine and quinine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:1143–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sidhu AB, et al. pfmdr1 Mutations contribute to quinine resistance and enhance mefloquine and artemisinin sensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:913–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidhu AB, et al. Decreasing pfmdr1 copy number in Plasmodium falciparum malaria heightens susceptibility to mefloquine, lumefantrine, halofantrine, quinine, and artemisinin. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:528–535. doi: 10.1086/507115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imwong M, et al. Gene amplification of the multidrug resistance 1 gene of Plasmodium vivax isolates from Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2657–2659. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01459-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwanarusk R, et al. Amplification of pvmdr1 associated with multidrug-resistant Plasmodium vivax. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:1558–1564. doi: 10.1086/592451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cravo PV, et al. Genetics of mefloquine resistance in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:709–718. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.709-718.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang H, et al. Genome-wide compensatory changes accompany drug-selected mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum crt gene. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dharia NV, et al. Use of high-density tiling microarrays to identify mutations globally and elucidate mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R21. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh A, Rosenthal PJ. Selection of cysteine protease inhibitor-resistant malaria parasites is accompanied by amplification of falcipain genes and alteration in inhibitor transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35236–35241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thaithong S, et al. Plasmodium falciparum: gene mutations and amplification of dihydrofolate reductase genes in parasites grown in vitro in presence of pyrimethamine. Exp. Parasitol. 2001;98:59–70. doi: 10.1006/expr.2001.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe J, Inselburg J. Establishing a physical map of chromosome No. 4 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994;65:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersson DI, et al. Evidence that gene amplification underlies adaptive mutability of the bacterial lac operon. Science. 1998;282:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergthorsson U, et al. Ohno's dilemma: evolution of new genes under continuous selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:17004–17009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirley MW, et al. Chromosome 9 from independent clones and isolates of Plasmodium falciparum undergoes subtelomeric deletions with similar breakpoints in vitro. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1990;40:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carret CK, et al. Microarray-based comparative genomic analyses of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum using Affymetrix arrays. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;144:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardiner DL, et al. Implication of a Plasmodium falciparum gene in the switch between asexual reproduction and gametocytogenesis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;140:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alano P, et al. Plasmodium falciparum: parasites defective in early stages of gametocytogenesis. Exp. Parasitol. 1995;81:227–235. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egan CM, et al. Recurrent DNA copy number variation in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1384–1389. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Repping S, et al. High mutation rates have driven extensive structural polymorphism among human Y chromosomes. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:463–467. doi: 10.1038/ng1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoue K, Lupski JR. Molecular mechanisms for genomic disorders. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2002;3:199–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.032802.120023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drake JW, et al. Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics. 1998;148:1667–1686. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seyfert AL, et al. The rate and spectrum of microsatellite mutation in Caenorhabditis elegans and Daphnia pulex. Genetics. 2008;178:2113–2121. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triglia T, et al. Amplification of the multidrug resistance gene pfmdr1 in Plasmodium falciparum has arisen as multiple independent events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:5244–5250. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dopman EB, Hartl DL. A portrait of copy-number polymorphism in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19920–19925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709888104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coghlan A, et al. Chromosome evolution in eukaryotes: a multi-kingdom perspective. Trends Genet. 2005;21:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ersfeld K. Fiber-FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization on stretched DNA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;270:395–402. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-793-9:395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reams AB, Neidle EL. Gene amplification involves site-specific short homology-independent illegitimate recombination in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:643–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su X, et al. Genetic linkage and association analyses for trait mapping in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:497–506. doi: 10.1038/nrg2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volkman SK, et al. A genome-wide map of diversity in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:113–119. doi: 10.1038/ng1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeffares DC, et al. Genome variation and evolution of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:120–125. doi: 10.1038/ng1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kidd JM, et al. Population stratification of a common APOBEC gene d eletion polymorphism. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gresham D, et al. Genome-wide detection of polymorphisms at nucleotide resolution with a single DNA microarray. Science. 2006;311:1932–1936. doi: 10.1126/science.1123726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sebat J. Major changes in our DNA lead to major changes in our thinking. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:S3–S5. doi: 10.1038/ng2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balu B, et al. High-efficiency transformation of Plasmodium falciparum by the lepidopteran transposable element piggyBac. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16391–16396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hall N, et al. A comprehensive survey of the Plasmodium life cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses. Science. 2005;307:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1103717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pain A, et al. The genome of the simian and human malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Nature. 2008;455:799–803. doi: 10.1038/nature07306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson TJ, et al. Geographical distribution of selected and putatively neutral SNPs in SE Asian malaria parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:2362–2374. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campbell PJ, et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiang DY, et al. High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]