Abstract

Good sleep is necessary for physical and mental health. For example, sleep loss impairs immune function, and sleep is altered during infection. Immune signalling molecules are present in the healthy brain, where they interact with neurochemical systems to contribute to the regulation of normal sleep. Animal studies have shown that interactions between immune signalling molecules (such as the cytokine interleukin 1) and brain neurochemical systems (such as the serotonin system) are amplified during infection, indicating that these interactions might underlie the changes in sleep that occur during infection. Why should the immune system cause us to sleep differently when we are sick? We propose that the alterations in sleep architecture during infection are exquisitely tailored to support the generation of fever, which in turn imparts survival value.

Modern sleep research began in 1953, with the discovery of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and the realization that sleep is an active process that consists of two distinct phases. More than half a century of intense investigation has yet to provide an unequivocal answer to the question, ‘Why do we sleep?’ Nonetheless, we are beginning to understand the contribution of sleep to fundamental brain processes1,2.

In contrast to our lack of knowledge regarding the precise functions of sleep, we do know why we have an immune system. Living organisms are subject to constant attack by various pathogens, and the complex networks of physical and biochemical components that constitute the immune system keep the organism alive. Like sleep research, the field of immunology is a relatively young discipline. It should therefore not come as a surprise that systematic investigations of interactions between sleep and the immune system have only been conducted in the past 25 years (TIMELINE).

Although we briefly touch on the general role of sleep in health and disease, in this Review we focus on those areas of research that are most relevant to sleep as a component of the host defence against microbial pathogens. Links between the CNS and the peripheral immune system are now well established, and much is known about the mechanisms by which bidirectional communication occurs between these systems3. As a result of neuro–immune interactions, sleep loss alters immune function and immune challenges alter sleep. Thus, chronic sleep loss results in pathologies that are associated with increases in inflammatory mediators, and inflammatory mediators that are released during immune responses to infection alter CNS processes and behaviour, including sleep.

One class of immunomodulators, cytokines, has been extensively studied both with respect to host responses to infection and as regulators of physiological sleep. In this Review, we briefly summarize what is known about cytokines in the brain as regulators of normal, physiological sleep and what is known about their role in mediating the changes in sleep that are induced by infectious agents. We focus on one cytokine, interleukin 1 (IL-1), which, together with tumour necrosis factor (TNF), is the most investigated cytokine with respect to sleep. We then address the mechanisms by which IL-1 affects neurons and neurotransmitters involved in sleep regulation. Thus, the role of the serotonergic system in the regulation of sleep and as a mediator of IL-1’s effects on sleep is reviewed. We conclude by proposing a hypothesis regarding the functional role of infection-induced alterations in sleep which suggests that the precise manner in which sleep is altered during infection facilitates the generation of fever and so promotes recovery.

Sleep in health and disease

Sleep is necessary for health

Although the brain gives us signals that indicate when we have had insufficient sleep, data show that more and more of us are ignoring these signals and reducing the amount of sleep we obtain each night. The percentage of adults who sleep less than 6 h per night is now greater than at any other time on record4. These survey data do not allow us to determine the extent to which the declining amounts of sleep are due to sleep disorders or to behavioural decisions, but it is clear that our current practice of sleeping less is largely driven by societal changes, including increased reliance on longer work hours and shift work, the trend for longer commute times, and increased accessibility to media of all sorts.

What are the consequences of sleep loss? Historically, it was widely thought that the only consequence of nighttime sleep loss was daytime sleepiness resulting in cognitive impairment. We now have compelling evidence that, in addition to cognitive impairment, sleep loss is associated with a wide range of detrimental consequences, with tremendous public-health ramifications. For example, short periods of sleep loss at the time of vaccination reduce the vaccine’s effectiveness5,6. Sleep loss is associated with increased obesity7,8 and with reduced levels of leptin and increased levels of ghrelin8,9, the combination of which increases appetite. Sleep loss is also associated with diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in a dose-related manner: individuals that report sleeping less than 6 h per night are ~1.7 times as likely, and those that report sleeping less than 5 h per night are ~2.5 times as likely, to have diabetes than individuals that obtain 7 h of sleep10. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension are also associated with sleep loss: the risk of a fatal heart attack increases 45% in individuals who chronically sleep 5 h per night or less11. Collectively, these examples demonstrate wide- ranging consequences of sleep loss on physical health. Obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease are pathologies that are characterized, in part, by inflammatory processes. The magnitude of the public-health burden imposed by these and other diseases underscores the importance of relationships between sleep and immune function and our efforts to understand them.

Sleep is disturbed during disease

We have all experienced the feelings of lethargy and fatigue associated with being sick. Some infections induce dramatic alterations in sleep. For example, recent cases of an encephalitis lethargica-like syndrome have been associated with streptococcal infections, during which severe sleep disruption occurs12. In addition, there is an extensive body of literature which demonstrates that the sleep of individuals infected with HIV is altered even before they show symptoms of AIDS13. Furthermore, infection with the parasite Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), results in extreme fragmentation of sleep and a complete loss of the diurnal rhythms of sleep and wakefulness14,15. Although most people fortunately do not encounter these catastrophic infections, we have all suffered colds or ‘the flu’, and sleep is altered during these more common infections as well16,17.

Cytokines and sleep

Immune responses during infection include alterations in the concentrations and patterns of immune signalling molecules called cytokines. The list of cytokines and chemokines that have been studied in laboratory animals or human subjects and demonstrated to affect sleep is extensive and includes IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, IL-15, IL-18, TNFα, TNFβ, interferon-α (IFNα), IFN-β, INF-γ and macrophage inhibitory protein 1β (also known as CCL4). Of these substances only two, IL-1β (hereafter referred to as IL-1) and TNFα (hereafter referred to as TNF), have been studied extensively enough to state that they are involved in the regulation of physiological (that is, spontaneous) sleep18–20. Evidence for a role for IL-1 and TNF in the regulation of physiological sleep has been derived from electrophysiological, biochemical and molecular genetic studies.

Cytokines participate in the regulation of sleep

Although most cytokines were first discovered in the peripheral immune system, several cytokines and their receptors have now been shown to be present in the CNS21–23. The CNS detects activation of the peripheral immune system through cytokine-induced stimulation of the vagus nerve, through actions of circulating cytokines at the cir-cumventricular organs and through active transport of cytokines from the periphery into the CNS (reviewed in REF. 3). However, cytokines are also synthesized de novo and released in the CNS by both neurons24–26 and glia23. Neurons that are immunoreactive for IL-1 and TNF are located in brain regions that are implicated in the regulation of sleep–wake behaviour, notably the hypothalamus, the hippocampus and the brainstem24,27. Signalling receptors for both IL-1 and TNF are also present in several brain areas, such as the choroid plexus, the hippocampus, the hypothalamus, the brainstem and the cortex, and are expressed in both neurons and astrocytes22,28,29.

IL-1 and TNF increase non-REM (NREM) sleep in several species (rat, mouse, monkey, cat, rabbit and sheep) irrespective of the route of administration18,20. NREM sleep that follows the administration of IL-1 or TNF has some characteristics of physiological sleep in the sense that it remains episodic and is easily reversible when the animal is stimulated. However, IL-1 generally causes fragmentation of NREM sleep30. The magnitude and duration of IL-1’s effects on NREM sleep depend on the dose30,31 and time31,32 of administration: very high doses are NREM-sleep suppressive31 and, in rodents, IL-1 is more effective in increasing NREM sleep when it is administered before the dark phase of the light–dark cycle31,32.

In accordance with the increase in NREM sleep that occurs after administration of IL-1 or TNF, antagonizing either of these cytokine systems reduces spontaneous NREM sleep. For example, inactivating or interfering with the normal action of IL-1 or TNF by means of antibodies, antagonists or soluble receptors reduces both spontaneous NREM sleep and the increase in NREM sleep that occurs after sleep deprivation18,20. Preventing the cleavage of active IL-1 from its inactive precursor also reduces spontaneous NREM sleep33. Furthermore, antagonizing these cytokine systems attenuates the increase in NREM sleep that follows excessive food intake or acute elevation of ambient temperature34, both of which are associated with enhanced production of either IL-1 or TNF. Moreover, knockout mice that lack the type 1 IL-1 receptor, the type 1 TNF receptor or both35 spend less time in NREM sleep than control mice.

Administration of cytokines has been repeatedly shown to suppress REM sleep18, but antagonizing endogenous cytokines in healthy animals with receptor antagonists, soluble receptors or antibodies either has no effect on REM sleep or only slightly reduces it33,36,37. These observations suggest that cytokines modulate REM sleep during pathological conditions but do not contribute to the regulation of normal, physiological REM sleep. Moreover, recent demonstrations that alterations in REM sleep in mice lacking both IL-1 receptor 1 and TNF receptor 1 occur independently of changes in NREM sleep suggest that these cytokines influence REM sleep through mechanisms that differ from those that are involved in NREM-sleep regulation35.

Finally, the fact that diurnal rhythms of IL-1 and TNF levels vary with the sleep–wake cycle provides further evidence for the involvement of IL-1 and TNF in physiological sleep regulation18,20. In rats, IL-1 and TNF mRNA and protein levels in the brain exhibit a diurnal rhythm with peaks that occur at light onset38; the light period in these rodents is the time when NREM sleep propensity is at a maximum. In humans, IL-1 plasma levels are highest at the onset of sleep39, and in cats cerebrospinal fluid IL-1 levels vary with the sleep–wake cycle40.

Cytokines mediate changes in sleep induced by infection

The data briefly reviewed above show that at least two pro-inflammatory cytokines are involved in regulating spontaneous, physiological NREM sleep. The question that then arises is whether these cytokines also mediate infection-induced alterations in sleep. Numerous systematic preclinical studies have demonstrated the extent to which infection alters sleep (reviewed in REFS 18,20,41). Although the precise alterations depend on the pathogen (bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites), the host and the route of infection, at some time during the course of most infections there is an increase in the amount of time spent in NREM sleep and a decrease in the amount of REM sleep.

Models in which replicating pathogens are used to make animals sick are the most clinically relevant, but these types of studies are difficult to perform and interpret because the disease state develops over periods of days to weeks and the responsiveness to the infection can differ dramatically between animals. However, the changes induced in sleep by infectious agents are due to immune responses to biologically active structural components of the pathogen. Indeed, administration of such biologically active structural components results in changes in sleep that mimic those observed during infection with replicating pathogens. For this reason, most mechanistic studies of infection-induced alterations in sleep have used these structural components to induce the many facets of immune responses in the absence of replicating pathogens. The most commonly used are bacterial cell wall components such as lipid A, lipopolysaccharide and muramyl peptide (or the synthetic muramyl dipeptide). These bacterial cell wall components induce strong antigenic responses such as upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1 and TNF42–44. When these bacterial cell wall components are administered to rabbits, rats, mice or humans (BOX 1), NREM sleep is increased and fragmented and REM sleep is suppressed45.

Box 1. Sleep and immunity in human volunteers.

There are some differences between laboratory animals and human subjects with respect to sleep–immune interactions. Most studies that use laboratory animals focus on the effects of host-defence activation on sleep and often include as outcome measures changes in immunomodulators in the brain. By contrast, the vast majority of studies that use human volunteers determine the effects of sleep loss on multiple facets of immunity, and immune-related outcome measures are almost always restricted to measures that can be obtained from whole blood, serum or plasma. The negative impact of sleep loss on public health is now recognized for pathologies that involve inflammatory processes, underscoring the importance of sleep to a healthy immune system.

It would be unethical to experimentally infect humans, but there are numerous clinical studies that describe the impact of HIV or trypanosome infection on sleep, all of which report that sleep is indeed altered. Healthy human volunteers under careful medical supervision have been subjected to host-defence activation by purified endotoxin101, an immune challenge in which there are no replicating pathogens. These studies show that humans are more sensitive to endotoxin than are laboratory animals; in humans, slow-wave sleep (the equivalent of non-rapid eye movement sleep in animals) is increased across the night by very low, subpyrogenic doses of endotoxin (less than one-thousandth of the per-bodyweight dose that elicits sleep responses in rats)102. As the endotoxin dose increases there are transient increases in slow-wave sleep, lasting approximately 1 h103. With even higher doses of endotoxin a much stronger host-defence response develops and, as in laboratory animals, sleep is severely disrupted102. This is probably due, in part, to increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which induces wakefulness and promotes arousal104,105.

As mentioned above, in contrast to the few reports of the effect of host-defence activation by endotoxin in humans, there have been numerous systematic studies in which human volunteers have been deprived of sleep and effects on immunity determined. The first study of the effects of sleep loss on immunity in humans seems to be that of Palmblad et al.106. They demonstrated that 48 h of sleep deprivation reduced phytohaemagglutinin-induced DNA synthesis in lymphocytes, an effect that persisted for 5 days. This study was followed by more than 50 other studies that showed effects of sleep deprivation on the human immune system. By way of example, 64 h sleep deprivation is associated with alterations in many aspects of immunity, including leukocytosis, increased natural killer cell activity and increased counts of white blood cells, granulocytes and monocytes107. According to recent reports, as little as 4 h of sleep loss in a controlled laboratory setting increases the production of interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor by monocytes — an effect that, bioinformatic analyses suggest, is mediated by the nuclear factor-κB inflammatory signalling pathway108. The number and scope of studies of human sleep loss and immunity exceed that which can be summarized in this Review, and so for recent comprehensive reviews see REFS 19,109.

Of importance to this discussion, the effects of bacterial cell wall components on sleep are attenuated or blocked if cytokine systems are antagonized. For example, increases in NREM sleep after lipopolysaccharide or muramyl dipeptide administration are blocked if the IL-1 system is antagonized33,46. These data suggest that infection-induced alterations in sleep are mediated by cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF. They also show that administration of cytokines or pathogen components can serve as a model of infection-induced alterations in sleep. The advantages of such models are that responses occur on a timescale of hours rather than days or weeks, that many facets of immune and behavioural responses to infection are elicited, and that it is relatively easy to titrate the magnitude of the desired response.

Serotonin and sleep

Sleep, like any behaviour, is regulated in the brain by multiple overlapping neuroanatomic circuits and related neurochemical systems. IL-1 and TNF interact with several of these systems, including the serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)) system47. The 5-HT system is one of the most investigated transmitter systems with respect to the regulation of sleep. In this section of the Review we briefly summarize the extensive body of literature that has demonstrated a role for the 5-HT system in regulating arousal states. Basic knowledge of 5-HT’s complex role in sleep regulation is necessary before one can fully understand how interactions between the IL-1 and 5-HT systems contribute to the regulation of sleep.

Observations in 1955 (REF. 48) by Brodie and colleagues that brain 5-HT depletion by reserpine induces sedation prompted investigation of the role of 5-HT in the regulation of sleep–wake behaviour. 5-HT has since been shown to regulate multiple physiological processes and behaviours, including vigilance states, mood, food intake, thermoregulation, locomotion and sexual behaviour49. The importance of the 5-HT system’s role in sleep regulation is supported by both experimental data and clinical observations: pharmacological manipulations that affect the 5-HT system by altering neurotransmitter synthesis, release, binding or re-uptake and metabolism result in profound alterations in sleep50. Sleep is also altered during clinical conditions such as depression, in which the functionality of the 5-HT system is thought to be chronically altered51.

5-HT promotes arousal but is necessary for NREM sleep

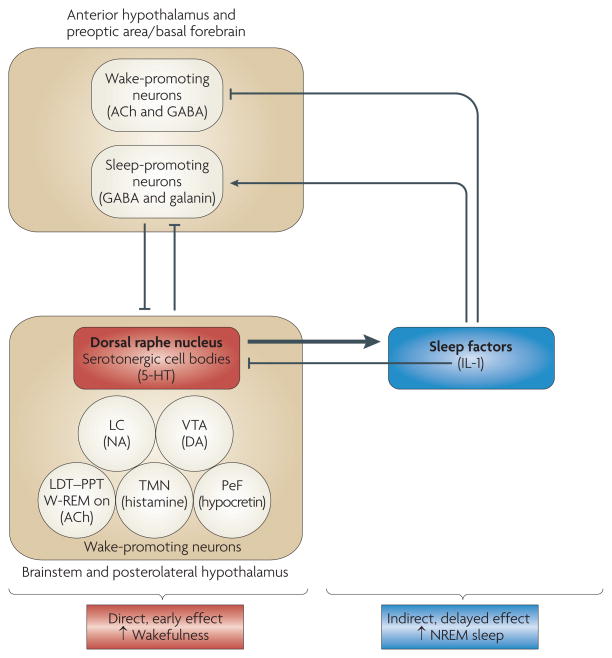

The exact role of 5-HT in sleep regulation has been subject to debate50,52. Data obtained in the 1960s and early 1970s suggested that the 5-HT system is necessary for NREM sleep: the destruction of raphe nuclei (which contain the cell bodies of 5-HT neurons) or the depletion of brain 5-HT by administration of the 5-HT synthesis inhibitor p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) induces insomnia that is selectively reversed by the 5-HT precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) 50,52. However, data obtained from the mid 1970s onwards suggested that 5-HT promotes wakefulness and suppresses NREM sleep. For instance, experimental manipulations that increase the release and synaptic availability of 5-HT, such as electrical stimulation of the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN), enhance wakefulness, whereas DRN inactivation enhances sleep53. In support of a wake-promoting role for 5-HT, a body of evidence has shown that the firing rates of serotonergic raphe neurons54–57 and 5-HT release58–61 are state-dependent: they peak during wakefulness and decrease during NREM sleep, and serotonergic cells become silent during REM sleep. In agreement with the interpretation that 5-HT is a wake-inducing substance, blockade of 5-HT2 receptors increases NREM sleep in rats and humans62. (A more detailed discussion of the role of 5-HT receptor subtypes in NREM-sleep regulation is beyond the scope of this Review.) 5-HT enhances wakefulness because serotonergic neurons in the DRN (together with other wake-promoting neurons, such as noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem locus coeruleus or hypocretinergic/orexinergic neurons in the hypothalamus) inhibit sleep-promoting neurons in the preoptic area, the anterior hypothalamus and the adjacent basal forebrain50,63 (FIG. 1). Noradrenergic and hypocretinergic/orexinergic wake-promoting neurons also stimulate each other’s activity64.

Figure 1. Serotonin initially increases wakefulness and subsequently increases non-rapid eye movement sleep.

Serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus, as well as other wake-promoting neurons located in the brainstem and the posterolateral hypothalamus, inhibit sleep-promoting neurons in the anterior hypothalamus, the preoptic area and the adjacent basal forebrain63,64. In turn, these rostral sleep-promoting neurons inhibit wake-promoting neurons in the brainstem and the posterolateral hypothalamus63,64. Serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)) also induces the synthesis and/or release of sleep-promoting factors, which subsequently inhibit rostral wake-promoting neurons and activate rostral sleep-promoting neurons of the hypothalamus and basal forebrain. Interleukin 1 (IL-1) may be one of the 5-HT-induced sleep factors because serotonergic activation induces IL-1 mRNA expression in the hypothalamus89 and IL-1 inhibits wake-promoting neurons in the hypothalamic preoptic area/basal forebrain82. IL-1 also inhibits wake-promoting serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus74,75. The schema is not intended to depict all interrelationships between the neuroanatomic regions and neurochemical systems involved in sleep regulation; rather, it is intended to illustrate the potential mechanisms by which 5-HT promotes wakefulness per se and at the same time stimulates the synthesis and/or release of sleep-promoting factors that then drive the sleep that naturally follows wakefulness52. ACh, acetylcholine; DA, dopamine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; LC, locus coeruleus; LDT–PPT, laterodorsal and pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei; NA, noradrenaline; NREM, non-rapid eye movement; PeF, perifornical region; TMN, tuberomammillary nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area; W-REM on, neurons that are active during both wakefulness and rapid eye movement sleep.

An attempt to integrate and reconcile these apparently contradictory data led to the hypothesis that 5-HT promotes wakefulness through direct actions and also stimulates the synthesis and/or release of sleep-promoting factors52. Data now support this dual-role hypothesis for the involvement of 5-HT in the regulation of arousal states. The purported sleep-promoting factors induced by 5-HT drive sleep by inhibiting wake-promoting neurons and stimulating sleep-promoting neurons (FIG. 1). Data obtained from rats and mice65–67 suggest that the role of 5-HT in the regulation of arousal states depends on the degree to which the 5-HT system is activated, the timing of the activation and the time that has passed since the activation (FIG. 1). When 5-HT release is enhanced in rats and mice through the administration of 5-HTP, the initial response is an increase in wakefulness and a reduction in NREM sleep65–67. This increase is fast, indicating that it is probably a direct effect of 5-HT. However, low doses of 5-HTP might not activate the 5-HT system sufficiently to stimulate sleep-inducing factors, a process that requires time. Following administration of higher physiological doses of 5-HTP, an increase in NREM sleep is apparent, after a delay, in both rats and mice65–67. This delayed increase in NREM sleep always occurs during the dark phase of the light–dark cycle, irrespective of the timing of 5-HTP administration65–67. Findings that 5-HTP administration increases the NREM sleep of rodents only during the dark phase suggest a fundamental property of the 5-HT system: the precise effects of serotonergic activation on sleep–wake behaviour depend not only on the extent but also on the timing of activation.

The data summarized above are in agreement with observations that acute administration in cats and rats of selective 5-HT re-uptake inhibitors first increases wake-fulness and then increases NREM sleep50. The first studies of the relationship between 5-HT and sleep, carried out in the 1960s, were based on behavioural observations and did not include polygraphically defined determinations of vigilance states. Nevertheless, these studies reported biphasic responses to 5-HT administration in which behavioural ‘activation’ was followed by ‘depression’ (REF. 50).

Serotonin suppresses REM sleep

Serotonergic neurons in the raphe nuclei, like noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus, are considered to be part of the systems that gate REM sleep by inhibiting the neurons that promote it68,69. In this view, suppressed serotonergic activity is permissive of REM-sleep generation, which is consistent with observations that pharmacological inhibition of the 5-HT system enhances REM sleep whereas increases in synaptic 5-HT availability inhibit it50. Accordingly, in rats and mice activation of the 5-HT system by administration of 5-HTP inhibits REM sleep, regardless of the dose and timing of administration65–67. The observation that mice that lack 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptor subtypes spend more time in REM sleep than control mice suggests that these receptor subtypes mediate the inhibitory effects of 5-HT on REM sleep70. Such a conclusion, supported by responses to pharmacological blockade of the same receptor subtypes70, of course does not rule out the possibility that 5-HT can also inhibit REM sleep by binding to other 5-HT receptor subtypes. At variance with the ‘REM-off’ role of 5-HT, observations that administration of a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist inhibits REM sleep in rats71 and that 5-HT7 receptor-knockout mice spend less time in this sleep phase72 suggest that 5-HT might have a facilitatory (or permissive) role in REM-sleep regulation through this specific receptor subtype. The role of 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C receptors in REM-sleep regulation is more complex70.

Interactions between IL-1 and 5-HT

Evidence consistently demonstrates that IL-1 has a role in regulating physiological NREM sleep by acting, in part, through well-defined neuromodulatory systems. For example, IL-1 stimulates the synthesis and/or release of growth hormone-releasing hormone, prostaglandin D2, adenosine and nitric oxide. Each of these substances is implicated in regulating or modulating NREM sleep, and antagonizing these systems attenuates or blocks IL-1-induced increases in NREM sleep. For an extensive review of the role of neuromodulatory systems in mediating cytokine effects on sleep, see REF. 73.

In addition to acting on these neuromodulatory systems, IL-1 acts directly on specific brain circuits and interacts with several neurotransmitters that have been implicated in regulating sleep. Thus, IL-1’s effects on NREM sleep could be mediated by actions on several neurotransmitter systems, although systematic investigations of the interactions between IL-1 and neurotransmitter systems that are relevant to the regulation of sleep remain to be conducted (BOX 2). Here, we focus on the interactions between IL-1 and the 5-HT system because these are the interactions for which the most data have accumulated during the past 10 years. We review the evidence that IL-1 enhances NREM sleep in part through opposing but complementary actions on the 5-HT system in two distinct neuroanatomical regions, namely the DRN and the preoptic area of the hypothalamus, and the adjacent preoptic area and basal forebrain (POA/BF), which receives serotonergic innervation from the DRN. We show that IL-1 has inhibitory actions on the cell bodies of the wake-promoting DRN 5-HT system and increases 5-HT release from axon terminals in the POA/BF.

Box 2. Effects of interleukin 1 on neurotransmitters involved in sleep regulation.

This Review focuses on interactions between interleukin 1 (IL-1) and the serotonergic system and, where relevant, on interactions between IL-1 and the GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-ergic system. There are also some published reports of interactions between IL-1 and other neurotransmitter systems that are relevant to sleep regulation, and here we present a brief overview.

Acetylcholine (Ach)

Pontomesencephalic cholinergic neurons have a key role in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep generation and, together with basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, in cortical desynchronization and activation64,68. IL-1 inhibits ACh release in the hippocampus in vivo110, inhibits ACh synthesis in vitro in cultured pituitary cells111 and increases acetylcholinesterase activity and mRNA expression in neuron–glia co-cultures and in vivo in the rat cortex112. Suppression of REM sleep by IL-1 (REF. 18) may be mediated by inhibition of pontomesencephalic cholinergic neurons.

Glutamate

Glutamate is widely used in the CNS. For instance, it is released by the neurons that project from the brainstem reticular formation, which is part of the ascending arousal system64. Many anaesthetics attenuate glutamate-mediated neurotransmission64. Interactions between IL-1 and glutamatergic neurotransmission have been investigated at length because of the involvement of glutamate excitotoxicity in neuron loss during stroke or chronic neurodegenerative disease113. Evidence suggests that IL-1 can potentiate or inhibit the effects of glutamate22,113. For instance, IL-1 decreases evoked glutamatergic excitatory responses in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons81.

Adenosine

Adenosine, which is a by-product of energy metabolism, promotes sleep by inhibiting cholinergic and non-cholinergic wake-promoting neurons in the basal forebrain114. Because IL-1 stimulates adenosine production115,116, this effect can further contribute to IL-1-induced increases in non-REM sleep. Moreover, IL-1-induced inhibition of glutamatergic responses (at least in the hippocampus) is mediated by adenosine81.

Monoamines

Brainstem noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus, dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area and histaminergic neurons in the posterior hypothalamus are all wake-promoting64. IL-1 activates these aminergic neurons and thereby enhances monoamine release in different brain areas47. Owing to their role in promoting wakefulness, IL-1-induced activation of aminergic neurons might counteract the increase in NREM sleep and thus maintain homeostasis.

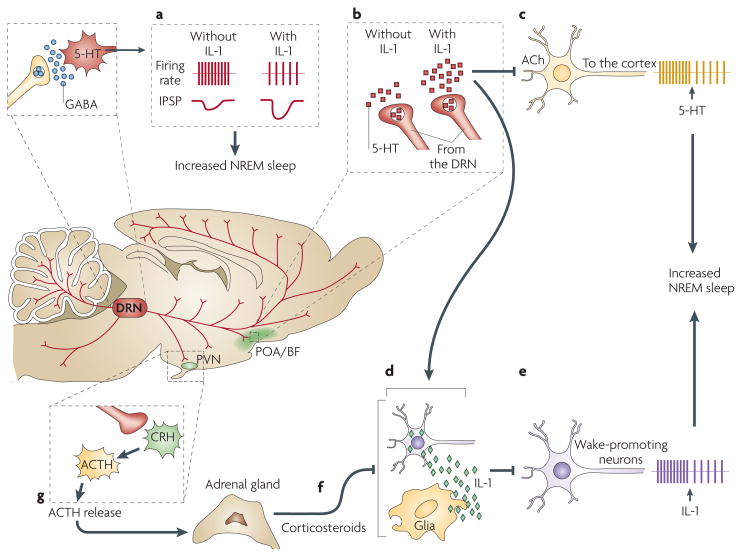

IL-1 actions in the DRN

IL-1 microinjection into the DRN of rats increases their NREM sleep74. In a brainstem slice preparation, bath application of IL-1 reduces the firing rates of DRN wake-promoting serotonergic neurons74,75 by enhancing GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-induced inhibitory postsynaptic potentials75 (FIG. 2a). Thus, IL-1 potentiates the physiological GABAergic inhibition that shapes the state-dependent discharge of DRN serotonergic neurons. IL-1 potentiates GABA signalling through multiple mechanisms: it recruits GABAA receptors to the cell surface76; it increases Cl− uptake by acting on GABAA receptors77; and it induces a delayed potentiation of the GABA-elicited Cl− current, an effect that is suppressed by the IL-1 receptor antagonist76. The observation that IL-1 potentiates the effects of GABA in the DRN is in agreement with data which demonstrate that IL-1 enhances GABA-induced hyperpolarization and inhibition in other brain regions where IL-1 acts both pre- and postsynaptically: IL-1 increases GABA release in anterior hypothalamic/pre-optic area slice preparations78 and in brain explants79 and enhances GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in hippocampal neurons80,81.

Figure 2. Interleukin 1 and serotonin interact at multiple sites in the brain to regulate non-rapid eye movement sleep.

A schematic representation of interactions in the brain among interleukin 1 (IL-1), serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) that are relevant for the regulation of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. In the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN), where IL-1 microinjections promote NREM sleep74, IL-1 reduces the firing rate of wake-active serotonergic neurons by enhancing the inhibitory effects of GABA75 (a). In the hypothalamic preoptic area/basal forebrain region (POA/BF), IL-1 stimulates 5-HT release from axon terminals59 (b). 5-HT, in turn, inhibits cholinergic neurons involved in cortical activation86 (c) and stimulates the synthesis of IL-1 (REF. 89) (d), which inhibits wake-promoting neurons (e) and activates a subset of sleep-promoting neurons in the POA/BF82. IL-1 in the POA/BF is under potent inhibitory homeostatic control by corticosteroids92 (f) released into the blood by the adrenal cortex. Corticosteroid levels depend on the activity of the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis92, which is stimulated by activation of the 5-HT system89 (g). ACh, acetylcholine; ACTH, adreno-corticotropic hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; IPSP, inhibitory postsynaptic potential; PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

IL-1 effects in the POA/BF

In the POA/BF, a brain area that is crucial for sleep regulation63,64, IL-1 directly inhibits wake-promoting neurons (FIG. 2e) and stimulates a subset of sleep-promoting neurons82. IL-1 also increases the number of c-FOS-immunoreactive neurons in the POA/BF83. The number of these c-FOS-immunoreactive neurons positively correlates with the amount of NREM sleep during the 2 h before sacrifice, suggesting that the stained neurons were active during this sleep phase and thus might be sleep-active neurons. In addition, IL-1 stimulates 5-HT release from axon terminals in the POA59 (FIG. 2b). IL-1 induces a tonic increase in 5-HT release but does not alter the state-dependent pattern of release — that is, the phasic increases in 5-HT release during wakefulness and the decreases during sleep are superimposed on the tonic IL-1-induced increase in 5-HT release59. The IL-1-induced enhancement of 5-HT release from axon terminals can result from local actions that are independent of the effects on serotonergic cell bodies in the DRN, because release from axon terminals is elicited by application of IL-1 directly into the hypothalamus84. The POA/BF is the only brain area where increasing serotonergic activity by administering 5-HTP restores physiological sleep in cats that have been made insomniac by PCPA administration85. 5-HT in the POA/BF might be essential for NREM sleep, because it hyperpolarizes and inhibits the cholinergic neurons that are responsible for cortical activation86 (FIG. 2c). The results of these studies suggest that IL-1 stimulates NREM sleep in part by enhancing axonal 5-HT release in the POA/BF, where IL-1 and 5-HT inhibit wake-promoting neurons. 5-HT is essential for the effects of IL-1 on NREM sleep to fully manifest, because depletion of brain 5-HT by PCPA administration87 or blockade of 5-HT2 receptors88 transiently interferes with IL-1-induced increases in NREM sleep.

Not only does IL-1 induce 5-HT release and inhibit wake-promoting neurons in the hypothalamus, but reciprocal interactions between the 5-HT system and the IL-1 system are also of importance. Increasing serotonergic activation with 5-HTP induces IL-1 mRNA transcription in the hypothalamus89 (FIG. 2d) during periods when NREM sleep is enhanced by the same treatment65. There is specificity to this effect as 5-HTP does not alter IL-1 mRNA in the hippocampus or brainstem89. The 5-HTP-induced increase in IL-1 mRNA may be part of a self-sustaining regulatory loop, because IL-1 induces its own synthesis90,91. As a consequence, IL-1 can amplify the 5-HTP-induced increase in IL-1 concentrations in the POA/BF, thus potentiating the inhibition of wake-promoting neurons in this region82 (FIG. 2e). Finally, IL-1 mRNA and protein are under potent homeostatic inhibitory control by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis92 (FIG. 2f), the activity of which is increased by the activation of the 5-HT system89 (FIG. 2g).

Collectively, the results of the studies reviewed suggest that the IL-1 and 5-HT systems engage in reciprocal interactions that contribute to the regulation of NREM sleep. In the POA/BF IL-1 enhances axonal 5-HT release and 5-HT stimulates the synthesis of IL-1, which inhibits wake-promoting neurons. IL-1 also inhibits wake-active serotonergic cell bodies in the DRN. Thus, IL-1 exerts opposite effects on serotonergic cell bodies and axon terminals. These effects complement each other and they both contribute to the same functional outcome: the enhancement of NREM sleep.

Why is sleep altered during sickness?

Sleep is clearly adaptive and much effort has been directed at determining its functions1,2,93,94. As we have reviewed, sleep is altered during infection. Infection increases the concentrations of cytokines, including IL-1, and the release of neurotransmitters, including 5-HT, in the brain, and interactions between IL-1 and 5-HT contribute to the regulation of sleep. We are beginning to understand how infection induces these changes, but it remains unknown why sleep is altered during sickness. We propose that altered sleep during infection, as a component of the acute-phase response and sickness behaviour, promotes recovery.

Is there any evidence to support the hypothesis that altered sleep during infection is a determinant of clinical outcome? Although it did not directly test this hypothesis, at least one study suggests that this might indeed be the case. Toth and colleagues95 retrospectively analysed data derived from long-term studies of bacterial or fungal infection-induced alterations in sleep in rabbits. The authors calculated for each animal a cumulative sleep-quality score that reflected both the duration and the intensity of NREM sleep. This approach allowed stratification of the outcome on the basis of whether the animals had high or low sleep-quality scores (good sleep or poor sleep, respectively) during the course of the infection. These cumulative sleep-quality scores were then correlated with the infective dose of the pathogen, multiple clinical parameters and the outcome. Analyses revealed that the infective dose of the pathogen differed between animals, and animals that received a higher pathogen dose generally had low cumulative sleep-quality scores. This suggests that the sicker the animal, the more disrupted its sleep. However, and of importance to this discussion, there were individual differences in the fates of animals that received the same infective dose: animals that survived had higher sleep-quality scores than animals that died. Although — as with any study that reports associations — this study did not demonstrate causality, and although it has yet to be repeated, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that dynamic changes in sleep during infection aid recovery.

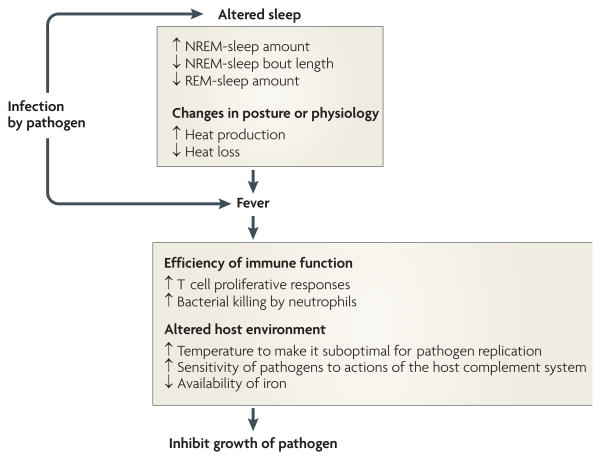

How might infection-induced alterations in sleep promote recovery? We propose that they facilitate the generation of fever. In this view it is fever that imparts survival value, and fever could not develop during infection if sleep architecture was not altered. This hypothesis is based on two extensive bodies of literature, one describing links between sleep and thermoregulation96 and the other indicating that fever is adaptive97.

The regulation of body temperature is coupled to sleep96: superimposed on the circadian rhythm of body and brain temperature are arousal state-dependent temperature changes (FIG. 3a). For example, brain and body temperature decrease during NREM sleep; the longer and more consolidated the NREM-sleep episode, the greater the decrease in brain or body temperature, until the regulated asymptote is reached. By contrast, brain temperature increases rapidly during REM sleep96,98 (FIG. 3a). In addition, thermoregulation is dependent on the sleep–wake state; for example, shivering does not occur during REM sleep96,99.

Figure 3. Sleep architecture is altered during fever.

The relationship between fever and changes in sleep architecture is apparent when interleukin 1 (IL-1) is administered to rats. a | A representative hypnogram depicting sleep–wake cycles of a male Sprague–Dawley rat demonstrates arousal state-dependent changes in brain temperature. Shown is a record of sleep–wake states (green line) and brain temperature (red line) for consecutive 12 s epochs recorded for 12 h after intracerebroventricular injection of vehicle. The injection was given at the beginning of the dark portion of the light–dark cycle. The expanded inset shows the arousal state-dependent changes in brain temperature that occur under normal conditions in a freely behaving rat. Brain temperature declines before entry into and during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, whereas it increases at the onset of and during REM sleep. Increases in brain temperature that are associated with wakefulness (wake) are of greater magnitude than those that occur during REM sleep. b | After intracerebroventricular injection of 5.0 ng IL-1 into the same rat as in part a, NREM sleep is fragmented, REM sleep is abolished (green line) and fever ensues (red line). The expanded inset shows the extent to which NREM sleep is fragmented during fever. This inset depicts the effects of IL-1 on sleep during the third post-injection hour, the same period presented in the expanded inset of part a. In this animal, the effects of IL-1 on NREM sleep and REM sleep are apparent for almost 6 h. Once NREM–REM sleep cycles reappear, arousal state-dependent changes become apparent and brain temperature subsides to control values.

Vertebrates and invertebrates develop fever in response to administration of pyrogens (fever inducers) or infection with pathogens. Data demonstrate increased survival when the host develops a moderate fever during bacterial or viral infections97. The survival value of fever to the host organism is conferred primarily by two mechanisms: facets of immune responses are potentiated at elevated body temperature, and the host environment is directly altered such that conditions for replication of the pathogen become less optimal97,100 (FIG. 4).

Figure 4. Proposed principles by which changes in sleep architecture promote recovery from infection.

Infection-induced alterations in sleep are such that increases in non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep provide energy savings, and short NREM-sleep bouts reduce heat loss. The reduction in REM sleep allows the animal to shiver. The combined changes in NREM and REM sleep facilitate the production of fever. Fever imparts survival value because it increases the efficiency of many facets of immune function and alters the host environment to make it less favourable for pathogen reproduction97.

However, fever is energetically demanding: metabolism must be increased to raise and then maintain body temperature. It has been estimated that the mean increase in metabolism is 13% for every 1°C increase in body temperature100. Increasing the amount of time spent in NREM sleep reduces the energy expenditure that is associated with competing activities, such as locomotion. But the changes in sleep architecture that occur during infection (suppressed REM sleep and increased but more fragmented NREM sleep) might have additional, fever-promoting benefits: shivering is crucial to the generation of fever but does not occur during REM sleep96. Perhaps for this reason REM sleep is eliminated during the early stages of fever (FIG. 3b). Furthermore, thermoregulatory mechanisms that reduce heat loss complement those involved in heat production (shivering) in the effort to increase body temperature. As heat dissipation normally occurs during NREM sleep, the fragmented nature of NREM sleep during the febrile response (FIG. 3b) may be viewed as a mechanism to reduce heat loss.

Data demonstrate that fever is adaptive and has evolved to increase survival in response to infection. Although it is unlikely that sleep has evolved solely to support the generation of fever during infection, the alterations in sleep in response to microbial pathogens are exquisitely designed to fulfil this role: the increase in NREM sleep conserves energy; the suppression of REM sleep allows shivering and, therefore, the production of fever; and the fragmentation of NREM sleep reduces heat loss.

Conclusions and future directions

Sleep is necessary for health as its loss or restriction is associated with multiple detrimental consequences. Although the interactions with neurotransmitters and neuromodulators through which cytokines enhance NREM sleep have been investigated at length, direct actions of cytokines on neurons in brain regions involved in the regulation of this sleep phase have only recently been determined. At present we know little about the mechanisms by which cytokines inhibit REM sleep. Investigating these mechanisms is important because REM sleep is disrupted in many pathologies that involve altered cytokine concentrations. For example, disturbed REM sleep and cytokine dysregulation are characteristic of major depression3. In addition to elucidating the mechanisms by which cytokines contribute to the regulation of the amount, pattern and distribution of sleep, crucial functional questions also wait to be answered. More systematic studies are required before we can understand the nature of cytokine involvement in altered sleep during sickness. Also of importance is the question of the extent to which alterations in sleep during sickness contribute to clinical outcome. Do alterations in sleep during infection contribute to survival as we propose and as is suggested by correlations between sleep quality and survival of infected rabbits95? Would recovery be facilitated if patients in hospitals were able to sleep better? Further investigation is required to better assess the mechanistic and functional relationships between sleep and morbidity and mortality, and to determine whether altered sleep promotes recovery.

Figure 5.

Timeline | A brief history of cytokines and sleep

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by US National Institutes of Health Grants MH64843 and HL080972, the Department of Anesthesiology of the University of Michigan Medical School, and the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Universita’ e della Ricerca, Italy.

- Encephalitis lethargica

An infectious process and an associated inflammatory response involving the brain and characterized by pronounced somnolence. The first cases were described in 1916 by the Viennese neurologist von economo. The pathology is typical of viral infections and is localized principally to the midbrain, the subthalamus and the hypothalamus. The causative agent has not been definitively determined

- Trypanosomiasis

A disease caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei and transmitted by several species of the tsetse fly. When the brain and meninges become involved, usually in the second year of infection, a chronic progressive neurologic syndrome results. Complete loss of the timing of sleep, alterations in sleep architecture, and later apathy, stupor and coma characterize the syndrome

- Sleep fragmentation

Interruption of sleep bouts by brief arousals such that the duration of the bout is reduced and transitions from one behavioural state to another occur more frequently

- Lipid A

The innermost, hydrophobic, lipid component of lipopolysaccharide. Lipid A anchors the lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall

- Lipopolysaccharide

A component (also known as endotoxin) of the outer wall of Gram-negative bacterial cell walls. it is composed of a lipid and polysaccharides joined by covalent bonds. it elicits strong immune responses through signalling pathways coupled to Toll-like receptor 4

- Muramyl dipeptide

The synthetic analogue of muramyl peptides, the monomeric building blocks of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Muramyl peptides are released by mammalian macrophages during the digestion of bacterial cell walls

- Inhibitory postsynaptic potential

(IPSP). Hyperpolarization of the membrane potential of a postsynaptic neuron. IPSPs are induced by a neurotransmitter released by a presynaptic neuron. Hyperpolarization reduces neuronal excitability because it is more difficult to trigger an action potential in a hyperpolarized neuron

- Acute-phase response

The reaction that develops in response to an injury or infection. It is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1) and is characterized by a local response (inflammation) and a systemic component, which includes the production of acute-phase proteins by hepatocytes, leukocytosis, fever and profound changes in lipid, protein and carbohydrate metabolism

- Sickness behaviour

The constellation of symptoms (decreased food intake, depressed activity, loss of interest in usual activities, disappearance of self-maintenance behaviours and altered sleep) that accompany responses to infection

Footnotes

FURTHER INFORMATION

Luca Imeri’s homepage: http://users.unimi.it/imeri/

Mark R. Opp’s homepage: http://www.med.umich.edu/anesresearch/opp.htm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: a hypothesis. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger JM, et al. Sleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assemblies. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:910–919. doi: 10.1038/nrn2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Percentage of adults who reported an average of ≤6 hours of sleep per 24-hour period, by sex and age group—United States 1985 and 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:933. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiegel K, Sheridan JF, Van Cauter E. Effect of sleep deprivation on response to immunization. JAMA. 2002;288:1471–1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1471-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange T, Perras B, Fehm HL, Born J. Sleep enhances the human antibody response to hepatitis A vaccination. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:831–835. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000091382.61178.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasler G, et al. The association between short sleep duration and obesity in young adults: a 13-year prospective study. Sleep. 2004;27:661–666. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:846–850. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb DJ, et al. Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863–867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayas NT, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:205–209. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dale RC, et al. Encephalitis lethargica syndrome: 20 new cases and evidence of basal ganglia autoimmunity. Brain. 2004;127:21–33. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman SE, Chediak AD, Kiel M, Cohn MA. Sleep disturbances in HIV infected homosexual men. AIDS. 1990;4:775–781. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buguet A, et al. The duality of sleeping sickness: focusing on sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:139–153. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundkvist GB, Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Why trypanosomes cause sleeping sickness. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:198–206. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake CL, et al. Effects of an experimentally induced rhinovirus cold on sleep, performance, and daytime alertness. Physiol Behav. 2000;71:75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00322-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettis R, et al. Impact of influenza treatment with oseltamivir on health, sleep and daily activities of otherwise healthy adults and adolescents. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:329–340. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200626060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opp MR. Cytokines and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opp M, Born J, Irwin M. In: Psychoneuroimmunology. Ader R, editor. Burlington, Massachusetts: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. pp. 579–618. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krueger JM, Obal FJ, Fang J, Kubota T, Taishi P. The role of cytokines in physiological sleep regulation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;933:211–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eriksson C, Nobel S, Winblad B, Schultzberg M. Expression of interleukin 1α and β, and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mRNA in the rat central nervous system after peripheral administration of lipopolysaccharides. Cytokine. 2000;12:423–431. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:734–744. doi: 10.1038/35094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garden GA, Moller T. Microglia biology in health and disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breder CD, Dinarello CA, Saper CB. Interleukin-1 immunoreactive innervation of the human hypothalamus. Science. 1988;240:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.3258444. The first demonstration that neurons contain IL-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marz P, et al. Sympathetic neurons can produce and respond to interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3251–3256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ignatowski TA, et al. Neuronal-associated tumor necrosis factor (TNFα): its role in noradrenergic functioning and modification of its expression following antidepressant drug administration. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;79:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breder CD, Tsujimoto M, Terano Y, Scott DW, Saper CB. Distribution and characterization of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-like immunoreactivity in the murine central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1993;337:543–567. doi: 10.1002/cne.903370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bette M, Kaut O, Schafer MK, Weihe E. Constitutive expression of p55TNFR mRNA and mitogen-specific up-regulation of TNFα and p75TNFR mRNA in mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:417–430. doi: 10.1002/cne.10877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ban EM. Interleukin-1 receptors in the brain: characterization by quantitative in situ autoradiography. Immunomethods. 1994;5:31–40. doi: 10.1006/immu.1994.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olivadoti MD, Opp MR. Effects of i.c.v administration of interleukin-1 on sleep and body temperature of interleukin-6-deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2008;153:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Opp MR, Obál F, Krueger JM. Interleukin-1 alters rat sleep: temporal and dose-related effects. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R52–R58. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.1.R52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lancel M, Mathias S, Faulhaber J, Schiffelholz T. Effect of interleukin-1β on EEG power density during sleep depends on circadian phase. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R830–R837. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.4.R830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imeri L, Bianchi S, Opp MR. Inhibition of caspase-1 in rat brain reduces spontaneous nonrapid eye movement sleep and nonrapid eye movement sleep enhancement induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:R197–R204. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00828.2005. This report that NREM sleep is reduced when cleavage of biologically active IL-1 from its inactive precursor is impeded provides additional evidence of a role for IL-1 in regulating physiological NREM sleep and in the alterations in NREM sleep that follow host defence activation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi S, Krueger JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor prevents warming-induced sleep responses in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1325–R1329. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baracchi F, Opp MR. Sleep-wake behavior and responses to sleep deprivation of mice lacking both interleukin-1β receptor 1 and tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:982–993. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Opp MR, Krueger JM. Anti-interleukin-1β reduces sleep and sleep rebound after sleep deprivation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R688–R695. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.3.R688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opp MR, Krueger JM. Interleukin 1-receptor antagonist blocks interleukin 1-induced sleep and fever. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R453–R457. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.2.R453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cearley C, Churchill L, Krueger JM. Time of day differences in IL1β and TNFα mRNA levels in specific regions of the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352:61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moldofsky H, Lue FA, Eisen J, Keystone E, Gorczynski RM. The relationship of interleukin-1 and immune functions to sleep in humans. Psychosom Med. 1986;48:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lue FA, et al. Sleep and cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1-like activity in the cat. Int J Neurosci. 1988;42:179–183. doi: 10.3109/00207458808991595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Opp MR, Toth LA. Neural-immune interactions in the regulation of sleep. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d768–d779. doi: 10.2741/1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turrin NP, et al. Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine mRNA induction in the periphery and brain following intraperitoneal administration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Gaekwad J, Wolfert MA, Boons GJ. Modulation of innate immune responses with synthetic lipid A derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5200–5216. doi: 10.1021/ja068922a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datta SC, Opp MR. Lipopolysaccharide-induced increases in cytokines in discrete mouse brain regions are detectable using Luminex xMAP technology. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;175:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger JM, Majde JA. Microbial products and cytokines in sleep and fever regulation. Crit Rev Immunol. 1994;14:355–379. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v14.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imeri L, Opp MR, Krueger JM. An IL-1 receptor and an IL-1 receptor antagonist attenuate muramyl dipeptide- and IL-1-induced sleep and fever. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R907–R913. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn AJ. Effects of cytokines and infections on brain neurochemistry. Clin Neurosci Res. 2006;6:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cnr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brodie BB, Pletscher A, Shore PA. Evidence that serotonin has a role in brain function. Science. 1955;122:968. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3177.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ursin R. Serotonin and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:55–69. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anisman H, Merali Z, Hayley S. Neurotransmitter, peptide and cytokine processes in relation to depressive disorder: comorbidity between depression and neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85:1–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jouvet M. Sleep and serotonin: an unfinished story. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:24s–27s. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00009-3. A historical review of 40 years of investigation into 5-HT’s role in regulating arousal state by the investigator who is best known for his contributions to this topic. Data are interpreted within the framework of the hypothesis that 5-HT promotes wakefulness but stimulates the synthesis or release of unknown sleep factors that induce subsequent sleep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cespuglio R, Gomez ME, Walker E, Jouvet M. Effets du refroidissement et de la stimulation des noyaux du systeme du raphe sur les etats de vigilance chez le chat. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1979;47:289–308. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cespuglio R, Faradji H, Gomez ME, Jouvet M. Single unit recordings in the nuclei raphe dorsalis and magnus during sleep-waking cycle of semi-chronic prepared cats. Neurosci Lett. 1981;24:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lydic R, McCarley RW, Hobson JA. Serotonin neurons and sleep. I Long term recordings of dorsal raphe discharge frequency and PGO waves. Arch Ital Biol. 1987;125:317–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGinty DJ, Harper RM. Dorsal raphe neurons: depression of firing during sleep in cats. Brain Res. 1976;101:569–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90480-7. This was the first study to demonstrate state-dependent activity of serotonergic neurons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trulson ME, Jacobs BL. Raphe unit activity in freely moving cats: correlation with level of behavioral arousal. Brain Res. 1979;163:135–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cespuglio R, et al. Voltammetric detection of the release of 5-hydroxyindole compounds throughout the sleep-waking cycle of the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1990;80:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00228853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gemma C, Imeri L, De Simoni MG, Mancia M. Interleukin-1 induces changes in sleep, brain temperature, and serotonergic metabolism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;272:R601–R606. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Portas CM, McCarley RW. Behavioral state-related changes of extracellular serotonin concentration in the dorsal raphe nucleus: a microdialysis study in the freely moving cat. Brain Res. 1994;648:306–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Portas CM, et al. On-line detection of extracellular levels of serotonin in dorsal raphe nucleus and frontal cortex over the sleep/wake cycle in the freely moving rat. Neuroscience. 1998;83:807–814. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dugovic C. Functional activity of 5-HT2 receptors in the modulation of the sleep/wakefulness states. J Sleep Res. 1992;1:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saper CB, Chou TC, Scammell TE. The sleep switch: hypothalamic control of sleep and wakefulness. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:726–731. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imeri L, Mancia M, Bianchi M, Opp MR. 5-hydroxytryptophan, but not L-tryptophan, alters sleep and brain temperature in rats. Neuroscience. 2000;95:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00435-2. The first of several papers by these authors to demonstrate that activation of the 5-HT system has a biphasic effect on arousal state, with initial wakefulness followed by subsequent NREM sleep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Imeri L, Bianchi S, Opp MR. Antagonism of corticotropin-releasing hormone alters serotonergic-induced changes in brain temperature, but not sleep, of rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1116–R1123. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00074.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morrow JD, Vikraman S, Imeri L, Opp MR. Effects of serotonergic activation by 5-hydroxytryptophan on sleep and body temperature of C57BL/56J and interleukin-6-deficient mice are dose and time related. Sleep. 2008;31:21–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCarley RW. Neurobiology of REM and NREM sleep. Sleep Med. 2007;8:302–330. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu J, Sherman D, Devor M, Saper CB. A putative flip-flop switch for control of REM sleep. Nature. 2006;441:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nature04767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adrien J, Alexandre C, Boutrel B, Popa D. Contribution of the “knock-out” technology to understanding the role of serotonin in sleep regulations. Arch Ital Biol. 2004;142:369–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hagan JJ, et al. Characterization of SB-269970-A, a selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:539–548. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hedlund PB, Huitron-Resendiz S, Henriksen SJ, Sutcliffe JG. 5-HT7 receptor inhibition and inactivation induce antidepressantlike behavior and sleep pattern. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Biochemical regulation of non-rapid-eye-movement sleep. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d520–d550. doi: 10.2741/1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manfridi A, et al. Interleukin-1β enhances non-rapid eye movement sleep when microinjected into the dorsal raphe nucleus and inhibits serotonergic neurons in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1041–1049. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brambilla D, Franciosi S, Opp MR, Imeri L. Interleukin-1 inhibits firing of serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus and enhances GABAergic inhibitory post-synaptic potentials. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1862–1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serantes R, et al. Interleukin-1β enhances GABAA receptor cell-surface expression by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway: relevance to sepsis-associated encephalopathy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14632–14643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller LG, Galpern WR, Dunlap K, Dinarello CA, Turner TJ. Interleukin-1 augments gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor function in brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tabarean IV, Korn H, Bartfai T. Interleukin-1β induces hyperpolarization and modulates synaptic inhibition in preoptic and anterior hypothalamic neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1685–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Feleder C, Arias P, Refojo D, Nacht S, Moguilevsky J. Interleukin-1 inhibits NMDA-stimulated GnRH secretion: associated effects on the release of hypothalamic inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2000;7:46–50. doi: 10.1159/000026419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zeise ML, Madamba S, Siggins GR. Interleukin-1β increases synaptic inhibition in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons in vitro. Regul Pept. 1992;39:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(92)90002-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luk WP, et al. Adenosine: a mediator of interleukin-1β-induced hippocampal synaptic inhibition. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4238–4244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04238.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alam MN, et al. Interleukin-1β modulates state-dependent discharge activity of preoptic area and basal forebrain neurons: role in sleep regulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03469.x. These authors demonstrated for the first time that IL-1 applied directly to the hypothalamus inhibits wake-active neurons. The paper also reported increases in discharge rates in a subset of sleep-active neurons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baker FC, et al. Interleukin 1β enhances non-rapid eye movement sleep and increases c-Fos protein expression in the median preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R998–R1005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00615.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shintani F, et al. Interleukin-1β augments release of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the rat anterior hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3574–3581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03574.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Denoyer M, Sallanon M, Kitahama K, Aubert C, Jouvet M. Reversibility of para-chlorophenylalanine-induced insomnia by intrahypothalamic microinjection of L-5-hydroxytryptophan. Neuroscience. 1989;28:83–94. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90234-0. These authors demonstrated that the anterior hypothalamus is the only brain region where 5-HTP rescues sleep in cats made insomniac by depletion of brain 5-HT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khateb A, Fort P, Alonso A, Jones BE, Muhlethaler M. Pharmacological and immunohistochemical evidence for serotonergic modulation of cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:541–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Imeri L, Bianchi S, Mancia M. Muramyl dipeptide and IL-1 effects on sleep and brain temperature after inhibition of serotonin synthesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;273:R1663–R1668. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imeri L, Mancia M, Opp MR. Blockade of 5-HT2 receptors alters interleukin-1-induced changes in rat sleep. Neuroscience. 1999;92:745–749. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gemma C, Imeri L, Opp MR. Serotonergic activation stimulates the pituitary-adrenal axis and alters interleukin-1 mRNA expression in rat brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00103-8. This was the first paper to report that activation of the serotonergic system alters IL-1 mRNA expression in the brain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dinarello CA, et al. Interleukin 1 induces interleukin 1. I. Induction of circulating interleukin 1 in rabbits in vivo and in human mononuclear cells in vitro. J Immunol. 1987;139:1902–1910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taishi P, Churchill L, De A, Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Cytokine mRNA induction by interleukin-1β or tumor necrosis factor α in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2008;1226:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Turnbull AV, Rivier C. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines: actions and mechanisms of action. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mignot E. Why we sleep: the temporal organization of recovery. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Siegel JM. Clues to the functions of mammalian sleep. Nature. 2005;437:1264–1271. doi: 10.1038/nature04285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Toth LA, Tolley EA, Krueger JM. Sleep as a prognostic indicator during infectious disease in rabbits. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1993;203:179–192. doi: 10.3181/00379727-203-43590. This retrospective analysis of data derived from almost 100 rabbits revealed associations between the quality of sleep and clinical symptoms, morbidity and mortality. Survival from infectious pathogens is associated with better quality sleep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Parmeggiani PL. Thermoregulation and sleep. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s557–s567. doi: 10.2741/1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kluger MJ, Kozak W, Conn CA, Leon LR, Soszynski D. The adaptive value of fever. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Obál F, Jr, Rubicsek G, Sary G, Obál F. Changes in the brain and core temperatures in relation to the various arousal states in rats in the light and dark periods of the day. Pflügers Arch. 1985;404:73–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00581494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Glotzbach SF, Heller HC. Central nervous regulation of body temperature during sleep. Science. 1976;194:537–538. doi: 10.1126/science.973138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kluger MJ. Fever It’s Biology, Evolution and Function. Princeton Univ. Press; Princeton: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pollmacher T, et al. Experimental immunomodulation, sleep, and sleepiness in humans. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;917:488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mullington J, et al. Dose-dependent effects of endotoxin on human sleep. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:R947–R955. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haack M, Schuld A, Kraus T, Pollmacher T. Effects of sleep on endotoxin-induced host responses in healthy men. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:568–578. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00008. Along with references 101 and 102, this paper demonstrated the effects on the sleep of healthy human volunteers of host defence activation by injection of endotoxin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Friess E, Wiedemann K, Steiger A, Holsboer F. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system and sleep in man. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1995;5:111–125. doi: 10.1016/0960-5428(95)00003-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Steiger A. Sleep and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical system. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:125–138. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Palmblad J, Pertrini B, Wasserman J, Kerstedt TA. Lymphocyte and granulocyte reactions during sleep deprivation. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:273–278. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197906000-00001. The first study of human subjects to specifically focus on the impact of sleep loss on immunity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dinges DF, et al. Leukocytosis and natural killer cell function parallel neurobehavioral fatigue induced by 64 hours of sleep deprivation. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1930–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI117184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, Collado-Hidalgo A, Cole S. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1756–1762. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marshall L, Born J. Brain-immune interactions in sleep. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2002;52:93–131. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(02)52007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rada P, et al. Interleukin-1β decreases acetylcholine measured by microdialysis in the hippocampus of freely moving rats. Brain Res. 1991;550:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carmeliet P, Van Damme J, Denef C. Interleukin-1 beta inhibits acetylcholine synthesis in the pituitary corticotropic cell line AtT20. Brain Res. 1989;491:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li Y, et al. Neuronal-glial interactions mediated by interleukin-1 enhance neuronal acetylcholinesterase activity and mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1–149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00149.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fogal B, Hewett SJ. Interleukin-1β: a bridge between inflammation and excitotoxicity? J Neurochem. 2008;106:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:379–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sperlagh B, Baranyi M, Hasko G, Vizi ES. Potent effect of interleukin-1β to evoke ATP and adenosine release from rat hippocampal slices. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;151:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhu G, et al. Involvement of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ releasing system in interleukin-1β-associated adenosine release. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;532:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rosenbaum E. Eine neue Theorie des Schlafes. Hirschwald; Berlin: Aug, 1892. Warum müssen wir schlafen? [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tigerstedt R, Bergman P. Niere und kreislauf. Arch Physiol. 1898;8:223–271. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Baylis W, Starling E. The mechanism of pancreatic secretion. J Physiol. 1902;28:325–353. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1902.sp000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]