Abstract

Molecular resistance mechanisms affecting the efficiency of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells are not fully understood. Amphiregulin (Areg) overexpression has been proposed to predict NSCLC resistance to gefitinib and we have established that Areg-overexpressing H358 NSCLC cells resist apoptosis. Here, we demonstrate that Areg prevents gefitinib-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells. We show that H358 cells are resistant to gefitinib in contrast to H322 cells, which do not overexpress Areg. Inhibition of Areg expression by small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) restores gefitinib sensitivity in H358 cells, whereas addition of recombinant Areg confers resistance in H322 cells. Areg knockdown overcomes resistance to gefitinib and induced apoptosis in NSCLC H358 cells in vitro and in vivo. Under gefitinib treatment, Areg decreases the expression of the proapoptotic protein BAX, inhibits its conformational change and its mitochondrial translocation. Thus, in the presence of Areg, gefitinib-mediated apoptosis is reduced because BAX is sequestered in the cytoplasm. This suggests that treatments using epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors may be poorly efficient in patients with elevated levels of Areg. These findings indicate the need for inhibition of Areg to enhance the efficiency of the EGFR inhibitors in patients suffering NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in the world. Non-small-cell Lung Cancers (NSCLC) account for ~80% of lung cancers. Once diagnosed, the 5-year survival rate of NSCLC reaches no >12% despite different treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery.1 Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies improving the prognosis of lung cancer patients are urgently needed.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is involved in the development of various human cancers. In NSCLC, EGFR is frequently overexpressed and associated with a poor prognosis of patients.2 In the last decade, a novel class of inhibitors targeting the kinase activity of the EGFR (the EGFR-TKI family) was developed to overcome the poor successes of classical chemotherapy. A member of this family, gefitinib, showed potent antitumor effects in clinical trials for NSCLC treatment after previous chemotherapy,3 but failed to improve the overall survival benefit in an unselected population.4 Predictive markers of gefitinib treatment sensitivity have therefore been extensively studied in order to identify patients likely to respond to EGFR-TKIs. EGFR gene somatic mutations have been found associated with response to gefitinib.5 These mutations activate the EGFR tyrosine kinase and are mainly associated with adenocarcinoma histology, never-smoking status, female gender, and Asian descent.6 An increased ErbB2/Her-2 gene copy number is another marker associated with gefitinib sensitivity.6 Other factors such as kRAS-activating mutation,6 MET amplification,7 and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) expression8 are predictors of resistance to gefitinib treatment in NSCLC. Unfortunately, no single factor examined so far, has been able to perfectly predict the sensitivity of patients to gefitinib treatment.

Amphiregulin (Areg), an EGF-related growth factor, is associated with shortened survival of patients with NSCLC and poor prognosis. A high level of Areg in the serum of patients with advanced NSCLC might have a diagnostic value for predicting a poor response to gefitinib.9 This suggests that Areg may induce gefitinib resistance in NSCLC. Our group previously reported the antiapoptotic activity of Areg in NSCLC cell lines,10 through the inactivation of the proapoptotic protein BAX.11 In this study, we show that gefitinib antitumor activity in NSCLC is significantly reduced in the presence of Areg, because of the inactivation of BAX. In addition, using in vivo models of NSCLC in mice, we present evidence that gefitinib efficiency is improved if expression of Areg is inhibited by small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) co-treatments.

Results

Areg inhibits gefitinib-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cell lines

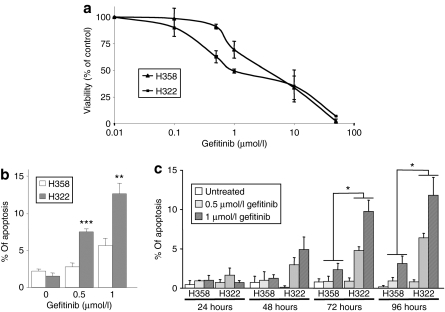

The H358 and H322 NSCLC cell lines, expressing wild-type EGFR, were chosen for an initial study on the effect of gefitinib. We first measured the effect of gefitinib on H358 and H322 cell proliferation. An MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay revealed that H322 cells were slightly more sensitive than H358 cells to this drug (Figure 1a). Approximately 1 µmol/l gefitinib inhibited the proliferation of H322 cells after 96 hours of treatment. In contrast, the IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) was 3–4 times higher in H358 cells. Flow cytometry analysis of propidium-iodide-stained H322 and H358 cells revealed that treatment with 1 µmol/l gefitinib for 4 days resulted in no marked change in the cell-cycle distribution (data not shown). However, 0.5 and 1 µmol/l gefitinib induced significant and dose-dependent apoptosis in H322 cells but not in H358, as shown with an active caspase-3 labeling assay (Figure 1b) or by counting the number of apoptotic cells with condensed nuclear DNA after Hoechst staining (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Gefitinib effect in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. (a) The MTT assay in H358 and H322 NSCLC cells treated with the indicated concentrations of gefitinib for 96 hours. (b,c) Effect of 0.5 or 1 µmol/l gefitinib on H358 and H322 cells. Apoptosis was analyzed after 96 hours by (b) detection of the active caspase-3 and flow cytometry or (c) after 24–96 hours after counting Hoechst-stained cells. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, for comparison between H358 and H322 cells.

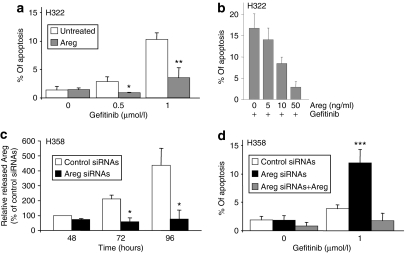

We previously showed that H358, but not H322 cells, secrete high levels of Areg, which induces the inhibition of apoptosis.10 To assess the involvement of Areg in gefitinib resistance, we added recombinant Areg in the culture medium of H322 cells. Areg prevented gefitinib-induced apoptosis (Figure 2a), in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2b). To confirm the role of Areg, we transfected the Areg-overexpressing H358 cells with anti-Areg siRNAs (Areg siRNAs), which inhibited 83% of secreted Areg level 96 hours after transfection, compared to control siRNAs (Figure 2c). Interestingly, although Areg siRNAs did not directly induce apoptosis, they significantly sensitized H358 cells to gefitinib, inducing three times more apoptosis than control siRNAs (Figure 2d). Again, Areg abolished this effect, demonstrating the specificity of the siRNAs. Altogether, these results show that Areg strongly reduces gefitinib proapoptotic activity.

Figure 2.

Areg inhibits gefitinib-induced apoptosis. (a) H322 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml recombinant human Areg and/or gefitinib as indicated. (b) H322 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Areg and 0.5 µmol/l gefitinib. (c) H358 cells were transfected with Areg or control siRNAs. The efficiency of Areg knockdown was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results are expressed as a rate of Areg released 48 hours after control siRNAs transfection and as mean ± SD (n = 3). (d) H358 cells were transfected with control or Areg siRNAs and treated with gefitinib and/or 50 ng/ml Areg. Apoptosis was scored after counting Hoechst-stained cells (a,b,d). Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, for comparison between treated and control cells. Areg siRNAs, amphiregulin small-interfering RNAs.

Areg inhibits gefitinib-induced apoptosis through BAX downregulation

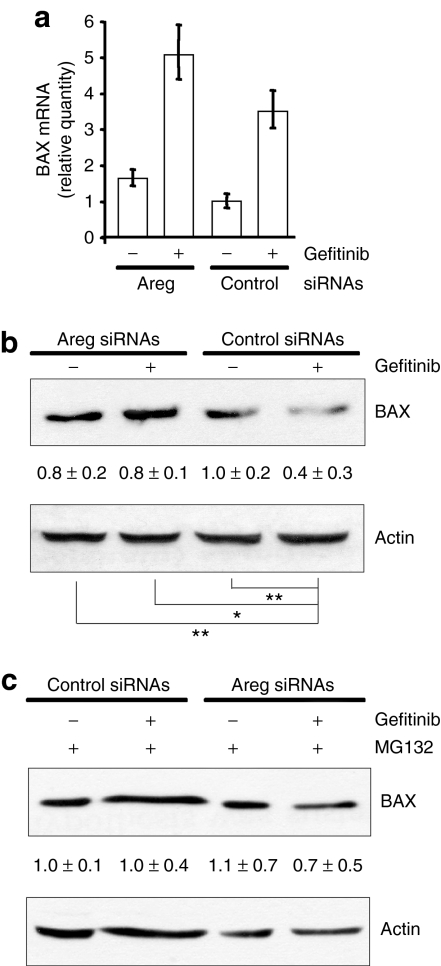

We previously showed that Areg prevents apoptosis by inactivating the Bcl2 family member BAX.10,11,12 Recent data linked gefitinib antitumor activity to proapoptotic protein of the Bcl2 family.13,14,15 We therefore investigated the relationship between gefitinib activity, Areg, and BAX in H358 cells. We first studied BAX mRNA and protein levels following exposure to gefitinib. Upregulation of BAX mRNA was observed by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR in gefitinib-treated H358 cells (Figure 3a), but, surprisingly, gefitinib significantly decreased the BAX protein level (Figure 3b). In parallel, we demonstrated that the Areg knockdown did not change the level of BAX mRNA, but prevented the disappearance of the BAX protein. These results suggest that gefitinib augments BAX mRNA transcription independently of Areg, while Areg decreases the level of BAX protein in the presence of gefitinib by a post-transcriptional mechanism. As we know that BAX proapoptotic function is regulated by proteasomal degradation,16 we studied the effect of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Figure 3c shows that MG132 prevented BAX downregulation in gefitinib-treated H358 cells, suggesting that Areg augments BAX proteasomal degradation.

Figure 3.

Areg decreases the BAX protein level. H358 cells were transfected with control or Areg siRNAs. As indicated, 0.5 µmol/l gefitinib and/or 3 µmol/l MG132 were added. (a) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for BAX mRNA on total RNA extracted from H358 cells. Relative gene expressions are expressed as a rate of BAX mRNA level after control siRNAs transfection. (b, c) Total cell lysates were subjected to western blotting using BAX antibody. Actin was used as protein level control. The values represent the relative intensity, quantified with ImageJ software, of BAX bands of treated samples to that of control cells, after being normalized to the respective actin and are represented by the mean ± SD (n = 4). *P ≤ 0.05 or **P ≤ 0.01 for comparison between control siRNAs in gefitinib-treated cells and the other treatments as indicated. Areg siRNAs, amphiregulin small-interfering RNAs.

Areg inhibits gefitinib-induced apoptosis by inactivation of BAX

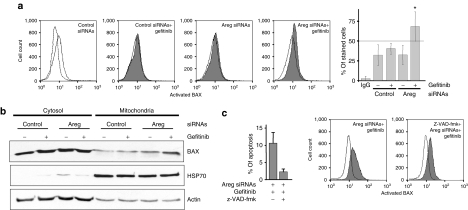

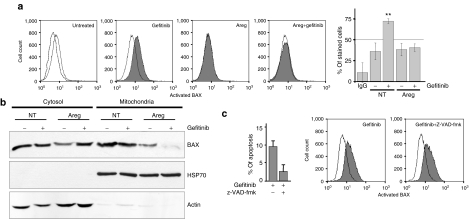

We analyzed the activation of BAX by flow cytometry using an antibody that recognizes the exposed N-terminus extremity of the activated form of BAX but not the protein in its inactive conformation.11,17 BAX immunofluorescence and the percentage of stained H358 cells (Figure 4a) were not modified by the gefitinib treatment, showing that BAX is not activated in these conditions. As well, inhibition of Areg expression using siRNAs had a limited influence on the exposure of the N-terminus moiety of BAX. However, the intensity of fluorescence and the percentage of stained cells were significantly increased when the cells were co-treated by Areg siRNAs and gefitinib (Figure 4a), suggesting that Areg inhibits BAX conformational change under a gefitinib treatment and thus confers resistance to BAX-mediated apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Areg inactivates BAX in H358 cells. H358 cells were transfected with control or Areg siRNAs. As indicated, 0.5 µmol/l gefitinib and/or 10 µmol/l z-VAD-fmk were added. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of BAX immunostaining using activated-BAX antibody. Dotted histogram and IgG, irrelevant antibody; open histogram, control cells; filled histogram, treated cells as indicated. Percentages of activated-BAX-stained cells were expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). *P < 0.05, more significant than control. (b) H358 cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. Both fractions extracts were subjected to western blotting using BAX antibody. Mitochondrial HSP70 was used for checking that cytosolic extracts were mitochondria-free and actin for loading control. (c) Apoptosis was scored after counting Hoechst-stained cells. Flow cytometry analysis of BAX immunostaining as described in a. Areg siRNAs, amphiregulin small-interfering RNAs.

Activated BAX translocates from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria, leading to cell apoptosis. To further analyze the influence of Areg on BAX subcellular localization, H358 cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. In untreated H358 cells, BAX was present mainly in the cytosolic fraction and to a lower extent in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 4b). Consistent with BAX activation detected by flow cytometry, gefitinib or Areg siRNAs alone did not modify BAX subcellular distribution, but the combination of Areg knockdown and gefitinib treatment induced its accumulation in the mitochondrial fraction. These results suggest that Areg inhibited BAX conformational change, and its mitochondrial translocation (Figure 4a,b). Interestingly, treating the cells with 10 µmol/l of the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk inhibited the gefitinib-induced apoptosis in Areg siRNAs–transfected H358 cells, but not BAX activation. This demonstrated that Areg prevents apoptosis by inactivating BAX and the subsequent caspase activation (Figure 4c).

To confirm our data, we further analyzed BAX activation and subcellular localization in the gefitinib-sensitive H322 cells. As expected, 0.5 µmol/l gefitinib treatment induced BAX activation in H322 cells. This effect was abolished in the presence of recombinant Areg (Figure 5a). Investigation of BAX subcellular localization showed that in untreated or Areg-treated H322 cells, BAX was present in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions (Figure 5b). However, Areg strongly inhibited BAX accumulation in the mitochondrial fraction in gefitinib-treated H322 cells. In addition, and as observed in H358 cells, 10 µmol/l z-VAD-fmk did not modify BAX activation in gefitinib-treated H322 cells, whereas apoptosis was inhibited (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Areg inactivates BAX in H322 cells. H322 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml Areg and/or 0.5 µmol/l gefitinib and/or 10 µmol/l z-VAD-fmk were added as indicated. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of BAX immunostaining using activated-BAX antibody. Dotted histogram and IgG, irrelevant antibody; open histogram, control cells; filled histogram, treated cells as indicated. Percentages of activated-BAX-stained cells were expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). **P < 0.01, more significant than control. (b) H322 cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. Both fractions extracts were subjected to western blotting using BAX antibody. Mitochondrial HSP70 was used for checking that cytosolic extracts were mitochondria-free and actin for loading control. (c) Apoptosis was scored after counting Hoechst-stained cells. Flow cytometry analysis of BAX immunostaining as described in a.

These observations strongly suggest that Areg inhibits the gefitinib-induced apoptosis by proteasomal degradation of BAX, but also by inhibition of BAX conformational activation and capacity to translocate to the mitochondria.

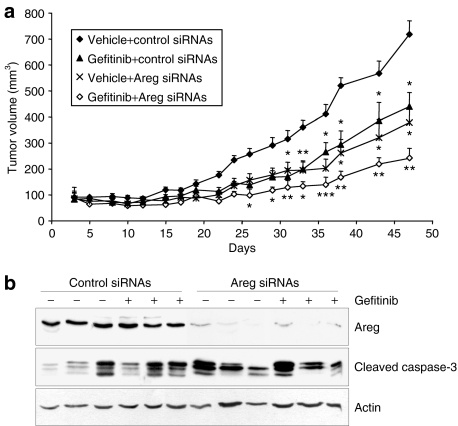

Antitumor efficacy of Areg and EGFR dual targeting in vivo

We then wanted to determine whether Areg depletion could enhance the antitumor activity of gefitinib in vivo. We tested the effects of gefitinib, Areg siRNAs, and their combination on the growth of H358 NSCLC xenograft tumors established in nude mice. Groups of mice treated with gefitinib or Areg siRNAs alone showed reduced tumor growth as compared with the control group (Figure 6a). This effect was significantly more pronounced in the group of mice treated with gefitinib and Areg siRNAs. At the end of the study, the mean tumor volume in the combined treatment group was 33% (P < 0.01) of the mean volume of the control group. As expected, western blot analysis of total protein extracts harvested from the H358 tumors at the end of this experiment showed that the levels of Areg were substantially decreased by Areg siRNAs (Figure 6b). Gefitinib or Areg siRNAs alone, as well as combined treatment, increased the level of cleaved-caspase-3 as compared to control. No significant difference between the treatments was observed in the proliferation index of tumoral cells (Ki67 nuclear protein immunolabelling, data not shown). Together, these findings suggest that gefitinib antitumor activity is more pronounced when Areg is knocked down.

Figure 6.

Effects of combined treatment with gefitinib and Areg knockdown in vivo. Effects of combined treatment with gefitinib and Areg siRNAs on growth of H358 xenograft tumors in athymic nude mice. The mice were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups. (a) Effect of gefitinib (10 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle, administered orally 5 days/week, and control or Areg siRNAs (16 µg/day, administered intraperitoneally 4 days/week) on tumor volume. Points, mean tumor volume (n = 8); bars, SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 for comparisons between treated and control for each series of experiments. (b) Effect of gefitinib and Areg siRNAs on the expression of Areg and activated-caspase-3 in H358 xenograft tumors, assessed by western blotting. Actin was used as loading control. Areg siRNAs, amphiregulin small-interfering RNAs.

Discussion

In this study, we show that Areg prevents gefitinib-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells through BAX inactivation. In the presence of gefitinib, Areg decreases BAX expression and inhibits its conformational change and its mitochondrial translocation. Areg knockdown by siRNAs restores the BAX expression level and its functional activation. This leads to a higher concentration of the active form of BAX in the mitochondria and thus to a stronger antitumor activity of gefitinib in NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo.

Gefitinib is a major molecule used in NSCLC treatment. However, resistance mechanisms to EGFR-TKI have limited its efficiency to a restricted group of patients, especially those presenting activating mutation in the adenosine triphosphate–binding site of EGFR-TKI.5,18 An increasing amount of evidence has suggested, however, that several pathways can confer resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy.6 We observed that H322 cells have gefitinib IC50 around 1 µmol/l, as already described,8 whereas various gefitinib sensitivities with IC50 ranging from ≤1 to ≥10 µmol/l are reported for H358 cells.8,15,19,20,21 Accordingly, we observed gefitinib IC50 around 4 µmol/l for H358 cells. Our data revealed that Areg-expressing H358 cells are less sensitive to apoptosis induced by 1 µmol/l gefitinib than H322 cells that do not secrete Areg. Moreover, Areg knockdown overcomes the resistance of H358 cells to gefitinib, whereas Areg protects the H322 cells from gefitinib-induced apoptosis, demonstrating the involvement of Areg in NSCLC cell resistance to gefitinib. The Areg autocrine loop is well characterized in the growth and survival of lung cancer cells.10,11 Areg is hardly detectable in lung tumor cells that are sensitive to gefitinib and is significantly overexpressed in gefitinib-resistant lung tumor cells.22 Overexpression of Areg is associated with shortened survival of patients with NSCLC, and a high level of Areg in the serum of patients with advanced NSCLC might have a high diagnostic value for predicting poor response to gefitinib.9 Areg might be a principal activator of the ligand-receptor autocrine pathway leading to the gefitinib resistance of NSCLC cells, independently of EGFR mutations.

Our results underline that Areg prevents gefitinib-induced apoptosis by decreasing BAX expression and activation. Both phenomena are additive and may explain the low sensitivity of H358 to gefitinib. Protein p53 is a major regulator of BAX.23 In our model, the mechanism of BAX regulation by Areg is independent of p53 because H358 cells are deleted for p53 and H322 cells express a nonfunctional mutated p53. The difference between BAX mRNA and its protein concentration suggested that Areg works at the post-transcriptional level. This is sustained by our result using a treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, which prevented BAX degradation, suggesting that Areg stimulates BAX proteasomal degradation. Interestingly, the regulation of BAX proapoptotic function by its ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation has already been described.16 We previously showed that H358 NSCLC cells resist BAX-mediated apoptosis due to the inhibition of its conformational change and of its translocation from the cytosol to the mitochondria.12 Here, we show that this phenomenon is strongly reducing the sensibility of NSCLC to gefitinib if Areg is present. In contrast, without Areg, gefitinib induces apoptosis by enhancing BAX expression and activation.

The relation between Areg and BAX activation is not fully understood. We previously observed that Areg stimulates cross talk between EGFR and IGF1R through a protein kinase C–dependent pathway that leads to BAX inactivation in NSCLC cells.10,11 Under gefitinib treatment, Morgillo et al. demonstrated that an EGFR/IGF1R heterodimer confers resistance to EGFR-TKI in NSCLC cell lines.8,24 We hypothesized that Areg confers resistance to gefitinib-induced apoptosis through EGFR/IGF1R cross talk and the protein kinase C–dependent survival pathway. In agreement, we observed the heterodimerization of IGF1R with EGFR in gefitinib-treated Areg-overexpressing H358 cells, but not in Areg-lacking H322 cells (Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, BAX can be sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive conformation by the auto-antigen Ku70 (refs. 25,26). Moreover, we have investigated the relationship between Areg and Ku70 in our NSCLC model and have demonstrated that Areg enhances BAX sequestration and inactivation by Ku70 (see ref. 27).

Our results have a direct impact on the efficiency of NSCLC treatment with gefitinib. The data showing enhanced apoptosis by Areg siRNAs suggest that Areg expression is an important factor for gefitinib sensitivity. In the recent literature, Areg has already been associated with resistance to anticancer treatments such as exemestane-based hormonotherapy28 and cisplatin-based conventional chemotherapy29 in breast cancer. Areg expression is associated with NSCLC's poor response to gefitinib.9,22 Here, we demonstrated that Areg is also involved in resistance to gefitinib. Areg might therefore be a new biomarker of NSCLC cell resistance to targeted therapies, such as the EGFR-TKI molecule gefitinib, and could be used to identify patients likely to respond to EGFR-TKI.

In addition to being a potential biomarker, Areg might also be a therapeutic target, especially in NSCLC. Indeed, Areg siRNAs treatment significantly reduced H358 tumor growth in vivo. siRNAs-based treatments in vivo are usually poorly efficient, because they are difficult to deliver and can be toxic.30 In our study, the significant antitumor efficacy of Areg siRNAs has shown neither weight loss nor treatment-related toxicity, indicating that appropriate amounts of siRNAs were used. In agreement, no inflammation and toxicity were reported with polyethylenimine (PEI)-complexed siRNAs in vivo.31 Moreover, specific antihuman-Areg siRNA were administered systematically (intraperitoneally) and managed to successfully silence in situ Areg production in tumors, demonstrating a suitable vectorization and efficacy. Several clinical trials are currently based on siRNAs administration or PEI vectorization (www.clinicaltrials.gov). Results of these studies may help to foresee the safety and efficacy of siRNAs and PEI delivery for the treatment of human malignancies. SiRNAs might thus play an increasing role in molecular therapies, especially in cancer treatment, after validation of human clinical trials.

The combination of Areg siRNAs and gefitinib co-treatments provides greater reduction of tumor growth in the absence of nonspecific toxicity. The 10 mg/kg dose of gefitinib used in this study was determined in preliminary experiments (data not shown) and was selected as the dose which provided suboptimal gefitinib antitumor activity without side effects. To our knowledge, this is the first study with combined treatments targeting both Areg and EGFR. These results demonstrate the value of specific anti-Areg targeting, alone or associated with EGFR-TKI, although the efficiency of systemic nonviral delivery of these siRNAs in vivo is still an issue. It is actually necessary to inject large and expensive quantities of siRNAs and this may limit their utilization in clinical oncology unless they are delivered by viral vectors.32,33 siRNAs directed against Areg delivered by adenovirus would be a suitable and potent strategy to inhibit its expression in gefitinib-based NSCLC therapy. Further studies are needed to validate whether the gefitinib combined with Areg targeting could enhance the objective response and survival rates in NSCLC patients. In addition, as the tumor regression was not complete, it will be important to investigate whether the surviving tumoral cells are resistant to gefitinib in vivo, in the same way as observed with 10 µmol/l gefitinib in vitro (Figure 1a). The development of a specific anti-Areg therapy would thus be suitable for treating these resistant cancers but could also benefit to other diseases where Areg is known as a bad prognostic biomarker.34

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and drug treatments. The human H358 and H322 NSCLC cell lines were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Cergy Pontoise, France) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Gefitinib was kindly provided by AstraZeneca France (Paris, France) and was prepared as 10 mmol/l stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at −20 °C. Recombinant human Areg was from Sigma-Aldrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France) and stored at −80 °C in dimethyl sulfoxide and dissolved in fresh medium just before use. MG132 and z-VAD-fmk were from Sigma-Aldrich, prepared as 25 µg/ml stock solution and stored at −20 °C. Cells were treated as indicated in figure legends.

Cell proliferation assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates overnight and treated with gefitinib for 96 hours. Cell proliferation was measured with the MTT assay, in accordance with the method described previously.35

Transfections. siRNAs targeting human Areg and nonspecific control siRNAs were synthesized by MWG Biotech (Roissy, France). Sequences of siRNAs targeting Areg were 5′-CGA-ACC-ACA-AAU-ACC-UGG-CTT-3′ and 5′-CCU-GGA-AGC-AGU-AAC-AUG-CTT-3′, and control siRNA sequence was 5′-CUU-ACG-CUC-ACU-ACU-GCG-ATT-3′. Transfection of duplex siRNAs was performed with Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), following the manufacturer's instructions. siRNAs were transfected into 60% confluent cells at the final concentration of 200 nmol/l. After transfection, the efficiency of Areg knockdown was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described.10

Apoptosis assays. Cells were harvested and pooled. The morphological changes related to apoptosis were assessed by fluorescence microscopy after Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/ml; Sigma) staining of cells and the percent of apoptotic cells was scored after counting at least 500 cells. Active caspase-3 was detected by flow cytometry using phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal active caspase-3 antibody kit (Becton Dickinson Pharmingen, Pont de Claix, France), following manufacturer's instructions. Analysis was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Pont de Claix, France).

Reverse transcriptase-qPCR. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). RNA concentration was determined using Eppendorf Biophotometer AG22331 (Hamburg, Germany) and RNA integrity was assessed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Massy, France). Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR for BAX mRNA (specific primers: forward 5′-ACTCCCCCCGAGAGGTCTT-3′ reverse 5′-CAAAAGTAGAAAAGGGCCGACAA-3′) was performed on Stratagene 14 MX3005P apparatus. Total RNA (800 ng) was subjected to complementary DNA synthesis with Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (Invitrogen) and subsequently amplified during 40 PCR cycles (10 minutes at 95 °C, cycles: 15 seconds at 95 °C, 1 minute at 60 °C) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Relative gene expression was calculated for each sample, as the ratio of BAX to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA copy number, thus normalizing BAX mRNA expression for sample-to-sample differences in RNA input.

Protein immunostaining by flow cytometry. Activated-BAX immunostaining analysis was performed as previously described.11,17 Briefly, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde 0.5% for 5 minutes at room temperature, washed and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/saponin 0.1% for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature in the presence of an anti-BAX rabbit polyclonal antibody (N-20, Tebu, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) raised against the peptide sequence amino acids of N-terminus BAX protein or rabbit irrelevant IgG (Becton Dickinson Pharmingen), washed, incubated for 30 minutes with Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) conjugate (1:1,000; Interchim, Montlucon, France), washed again and resuspended in PBS. All antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 0.1% saponin and 1% bovine serum albumin. Analysis was performed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest software. Green fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and detected at 500–550 nm.

Immunoblotting. Cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and incubated in lysis buffer (10 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 120 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 1 mmol/l dithiothreitol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Protein content was assessed by the Bio-Rad D C Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Ivry sur Seine, France). Western blotting was done using anti-BAX (1/3,000; Becton Dickinson Pharmingen), anti-Areg (1/100; Abcam, Paris, France), anti-HSP70 (1/5,000; Affinity BioReagent, Brebières, France), or anti-cleaved-caspase-3 (Asp 175, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling, St Quentin les Yvelines, France) antibodies. To ensure equal loading and transfer, membranes were also probed for actin using antiactin antibody (1/1,000; Sigma). Western blotting was further processed by standard procedures and revealed by chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Orsay, France).

Subcellular fractionation. Cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions using the Pierce Mitochondria Isolation Kit (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brebières, France) according to manufacturer's instructions. Both fractions' extracts were assessed for protein content using the Bio-Rad D C Protein Assay kit, and 20 µg of proteins were subjected to electrophoresis and analyzed by western blotting for BAX content. The relative purity of fractions was ascertained by western blotting using antimitochondrial HSP70 as a marker of mitochondria. The equal loading and transfer were ensured by reprobing the membranes using antiactin antibody.

In vivo model. The effect of the combination of gefitinib and anti-Areg siRNAs was measured on established subcutaneous tumor bearing mice. All the animal experiments were performed in agreement with the European Economic Community guidelines and the “Principles of laboratory animal care” (National Institutes of Health publication No. 86-23 revised 1985). The experimental protocol was submitted to ethical evaluation and the experiment received the accreditation number was #0128. Human lung adenocarcinoma H358 cells were harvested, and 20 × 106 cells in PBS were injected subcutaneously into the flank of female NMRI nude mice (6–8 weeks old; Janvier, Le Genest Saint Isle, France). When tumor diameters reached 5 mm, the mice were randomized in four experimental groups (10 mice/group). Group 1 (control mice) received control siRNAs and a vehicle (Tween-80/5% glucose), group 2 received gefitinib and control siRNAs, group 3 received Areg siRNAs and a vehicle, and group 4 received both Areg siRNAs and gefitinib. In vivo transient transfections were carried out using jetPEI (PolyPlus Transfection, Strasbourg, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Complexes resulted in siRNA/PEI (N/P) ratio of 8 as suggested for DNA by the manufacturer and as determined as optimal for siRNAs in pilot experiments (data not shown). A volume of 16 µg/day of PEI-complexed siRNAs were injected intraperitoneally, 4 times a week. Gefitinib (10 mg/kg/day) in Tween-80/5% glucose was administered per os 5 times a week. Tumor growth was quantified by measuring twice a week the tumors in two dimensions with a Vernier caliper. The volume was calculated as follow: a × b2 × 0.4, where a and b are the largest and smallest diameters, respectively.36 Results are expressed as volume ± SEM. Mice bearing necrotic tumors or tumors ≥1.5 cm in diameter were euthanized immediately. On day 47, all mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected to determine whether the combination of gefitinib- and Areg siRNAs–induced apoptosis by western blotting.

Statistical analyses. Statistical significance of differences in control cells versus treated cells was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney test. Means comparisons among mice groups and statistical significance of differences in tumor growth in the combination treatment group and in single-agent treatment groups were analyzed by analysis of variance test. Statistics were done using the Statview 4.1 software (Abacus Concept, Berkeley, CA). In all statistical analyses, two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR and IGF1R. Whole-cell extracts from H358 and H322 cells treated with 0.5 μM gefitinib for 96 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with EGFR antibody (Santa Cruz) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with IGF1R (Santa Cruz) or EGFR antibodies. IgG: immunoglobulin control for immunoprecipitation, used as negative control. Input: cell lysates that are not subjected to immunoprecipitation.

Supplementary Material

Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR and IGF1R. Whole-cell extracts from H358 and H322 cells treated with 0.5 μM gefitinib for 96 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with EGFR antibody (Santa Cruz) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with IGF1R (Santa Cruz) or EGFR antibodies. IgG: immunoglobulin control for immunoprecipitation, used as negative control. Input: cell lysates that are not subjected to immunoprecipitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank AstraZeneca for gefitinib. This work was supported by grants and research fellowship from La Ligue contre le Cancer, comité de la Drôme; EpiPro program (InCa).

REFERENCES

- Guessous I, Cornuz J., and , Paccaud F. Lung cancer screening: current situation and perspective. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:304–311. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaggi G, Novello S, Torri V, Leonardo E, De Giuli P, Borasio P, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression correlates with a poor prognosis in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:28–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, von Pawel J, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J., and , Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgillo F, Kim WY, Kim ES, Ciardiello F, Hong WK., and , Lee HY. Implication of the insulin-like growth factor-IR pathway in the resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells to treatment with gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2795–2803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa N, Daigo Y, Takano A, Taniwaki M, Kato T, Hayama S, et al. Increases of amphiregulin and transforming growth factor-alpha in serum as predictors of poor response to gefitinib among patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9176–9184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurbin A, Dubrez L, Coll JL., and , Favrot MC. Inhibition of apoptosis by amphiregulin via an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-dependent pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49127–49133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurbin A, Coll JL, Dubrez-Daloz L, Mari B, Auberger P, Brambilla C, et al. Cooperation of amphiregulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibits Bax- and Bad-mediated apoptosis via a protein kinase C-dependent pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19757–19767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413516200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrez L, Coll JL, Hurbin A, Solary E., and , Favrot MC. Caffeine sensitizes human H358 cell line to p53-mediated apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial translocation and conformational change of BAX protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38980–38987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DB, Halmos B, Kumar A, Schumer ST, Huberman MS, Boggon TJ, et al. BIM mediates EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced apoptosis in lung cancers with oncogenic EGFR mutations. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1669–1679; discussion 1680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Somwar R, Politi K, Balak M, Chmielecki J, Jiang X, et al. Induction of BIM is essential for apoptosis triggered by EGFR kinase inhibitors in mutant EGFR-dependent lung adenocarcinomas. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg MS, Kuroda J, Puthalakath H, Huang DC., and , Strasser A. Gefitinib-induced killing of NSCLC cell lines expressing mutant EGFR requires BIM and can be enhanced by BH3 mimetics. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1681–1689; discussion 1690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsel AD, Rathaus M, Kronman N., and , Cohen HY. Regulation of the proapoptotic factor Bax by Ku70-dependent deubiquitylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5117–5122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706700105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desagher S, Osen-Sand A, Nichols A, Eskes R, Montessuit S, Lauper S, et al. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:891–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Kinoshita I, Sukoh N, Harada M, Yokouchi H, et al. A phase II trial of gefitinib as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Jänne PA, Mermel C, Pearlberg J, Mukohara T, Fleet C, et al. ErbB-3 mediates phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in gefitinib-sensitive non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3788–3793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409773102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordella R, Bell DW, Haber DA., and , Settleman J. Gefitinib-sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung cancer activate anti-apoptotic pathways. Science. 2004;305:1163–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1101637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy S, Mukohara T, Hansen M, Meyerson M, Johnson BE., and , Jänne PA. Gefitinib induces apoptosis in the EGFRL858R non-small-cell lung cancer cell line H3255. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7241–7244. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi S, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, Furukawa C, Tsunoda T, Yano S, et al. Prediction of sensitivity of advanced non-small cell lung cancers to gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3029–3043. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, et al. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgillo F, Woo JK, Kim ES, Hong WK., and , Lee HY. Heterodimerization of insulin-like growth factor receptor/epidermal growth factor receptor and induction of survivin expression counteract the antitumor action of erlotinib. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10100–10111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HY, Lavu S, Bitterman KJ, Hekking B, Imahiyerobo TA, Miller C, et al. Acetylation of the C terminus of Ku70 by CBP and PCAF controls Bax-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2004;13:627–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder S, Plesca D, Kinter M., and , Almasan A. Interaction of a cyclin E fragment with Ku70 regulates Bax-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3511–3520. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01448-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busser B, Sancey L, Josserand V, Niang C, Khochbim S, Favrot MC.et al. Amphiregulin promotes resistance to gefitinib in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells by regulating Ku70 acetylation Mol Therthis issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Masri S, Phung S., and , Chen S. The role of amphiregulin in exemestane-resistant breast cancer cells: evidence of an autocrine loop. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2259–2265. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein N, Servan K, Girard L, Cai D, von Jonquieres G, Jaehde U, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway analysis identifies amphiregulin as a key factor for cisplatin resistance of human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:739–750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706287200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguino A, Lopez-Berestein G., and , Sood AK. Strategies for in vivo siRNA delivery in cancer. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:248–255. doi: 10.2174/138955708783744074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet ME, Erbacher P., and , Bolcato-Bellemin AL. Systemic delivery of DNA or siRNA mediated by linear polyethylenimine (L-PEI) does not induce an inflammatory response. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2972–2982. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9693-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargiotis O, Chetty C, Gondi CS, Tsung AJ, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of siRNA against MMP-2 mRNA results in impaired invasion and tumor-induced angiogenesis, induces apoptosis in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:4830–4840. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Yoo JY, Kim JH, Kim J, Huang JH, Zhang SN, Kang YA, et al. Short hairpin RNA-expressing oncolytic adenovirus-mediated inhibition of IL-8: effects on antiangiogenesis and tumor growth inhibition. Gene Ther. 2008;15:635–651. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto F, Yagi H, Suzuki SO, Oki E, Tsujioka H, Hachisuga T, et al. Validation of HB-EGF and amphiregulin as targets for human cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD., and , Mitchell JB. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987;47:936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjønniksen I, Storeng R, Pihl A, McLemore TL., and , Fodstad O. A human tumor lung metastasis model in athymic nude rats. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5148–5152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR and IGF1R. Whole-cell extracts from H358 and H322 cells treated with 0.5 μM gefitinib for 96 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with EGFR antibody (Santa Cruz) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with IGF1R (Santa Cruz) or EGFR antibodies. IgG: immunoglobulin control for immunoprecipitation, used as negative control. Input: cell lysates that are not subjected to immunoprecipitation.