Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present selected findings of a grounded theory study which aims to explore individual processes and desired outcomes of recovery from recurrent health problems in order to build up a theoretical framework of recovering in an Irish context.

Volunteers include mental health service users or participants of peer support groups who have experienced recurrent mental health problems for two or more years, consider themselves in improvement, and are willing to participate in individual interviews. The current paper is based on the analysis of 15 audio recorded and transcribed interviews.

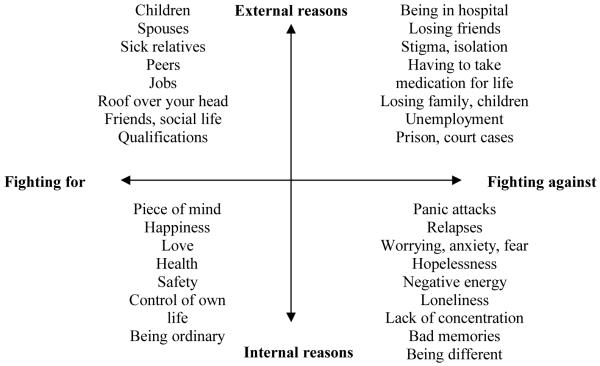

We identified two open codes of ‘giving up’ and ‘fighting to get better’. Giving up was associated with accepting a passive identity of a chronic ‘mental patient’ and a lack of intrinsic motivation to get better. Fighting had both positive (fighting for) and negative (fighting against) dimensions, as well as internal and external ones.

The ‘fight’ for recovery entailed substantial and sometimes risky effort. Starting such fight required strong self-sustained motivation. Service providers may need to discuss internal and external motivators of fighting for recovery with service users, with a view to including such motivators in the care plans.

Keywords: interviews, mental health services, mental illness, recovery, grounded theory

Introduction

Concepts and Processes of Recovery

As elsewhere in the world, the concept of recovery is now central to mental health policy and service planning in Ireland (Department of Health and Children 2006). The concept of recovery emerged from the consumer movement in the USA during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Roberts & Wolfson 2004). Since that time, recovery has been increasingly gaining attention of mental health researchers, service providers and policy makers in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and Europe. For example, user-led perspectives on recovery and recovery-oriented approach to service provision have been incorporated in the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines for schizophrenia since 2002 (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2002).

Though there is still no universally accepted definition of recovery, the meaning of the word ‘recovery’ has expanded from the absence of symptoms that characterise a medical condition to a broader perspective of social and occupational functioning (Craig 2008). Individual life circumstances, such as the absence or presence of friends or significant others, independent accommodation, or employment opportunities are important for both alleviating symptoms, sometimes referred to as the first order change, and social integration and inclusion, referred to as the second order change (Onken et al. 2007). Both the individual (internal) and environmental (external) factors and circumstances are dynamically linked and can either promote or hinder personal recovery (Onken et al. 2007).

However consumer views on recovery are not fully compatible with the medical priority of the alleviation of symptoms over social integration and inclusion. Consumer movement argues that the concepts of their recovery should include self-esteem, adjustment to disability, empowerment, and self-determination (Anthony 1993). The most widely accepted consumer definition of recovery is that of Anthony (1993): ‘A deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by the illness’ (p.13). Recovery as a multifaceted process of changing the way of living one’s life seems to be one of the inherent features of consumer definitions of recovery.

Several studies describe specific processes and stages of consumer recovery. For example, a qualitative longitudinal study in the USA (Spaniol et al. 2002) represents the process of recovery as having phases, dimensions, indicators and barriers. The researchers identified three broad general stages of recovery: being overwhelmed by the disability, struggling with the disability, and living beyond the disability. Three major steps associated with the process of recovery were described as follows: developing an explanatory framework for understanding the experience of serious mental illness; getting control over the illness; and moving into meaningful, productive and valuable roles in the society.

The review of international studies of recovery experiences (Andersen et al. 2003) highlighted four key component processes of recovery: finding hope, re-establishment of identity, finding meaning in life, and taking responsibility for recovery. Researchers identified five sequential stages: moratorium, awareness, preparation, rebuilding, and growth. Elements of the final stage of growth in this model are similar to the six factors of psychological well-being, which include personal growth, self acceptance, autonomy, positive relationships, environmental mastery, and purpose in life (Ryff 1995).

Despite the abundance of studies describing various aspects and processes of recovery, theoretical framework of recovery acceptable by the majority of persons with mental health problems, service providers and community groups has yet to be consolidated both at local and international levels (Ramon et al. 2007). To become fully accepted by the mental health practice, the consumer definition of recovery needs to be further explored and conceptualised, in order to accommodate both integration and inclusion, traditionally viewed by services as the second order change, and alleviation of symptoms, often viewed as secondary by consumers.

Some researchers argue that universal processes of recovery may be difficult to conceptualise due to various degrees of institutionalisation of service users across cultures (Allott et al. 2002). A vision of what ‘recovery’ is may be influenced by different underlying cultural, political and economic values. For example, political agendas of US and UK mental health service users may be different (Hatzidimitriadou 2002). The author suggests that the UK service user groups may not be as radical and are not necessarily against traditional mental health system as a whole, as compared to the US consumers. As she points out, in the USA the mental health system agenda has been largely driven by pharmaceutical companies due to the high levels of consumerism and individualism in the society. In the UK the welfare system is still the main provider of mental health services, and the users who depend on the services are more interested in their improvement rather than abolishment or substitution of services with user-led ones (Hatzidimitriadou 2002).

There may be a danger that by using the word ‘recovery’ without looking into its meaning, adopting the ‘recovery-oriented’ prefix and some general ‘universal’ concepts of recovery, mental health services may simply repackage their services without proper understanding of the major recovery principles (Ralph et al. 2000). Moreover, mental health services which are not fully cognisant of recovery aspirations of their service users may inadvertently create barriers to recovery (Tooth et al. 2003, Lilja & Hellzen 2008). Some persons may describe their hospital experiences as a constant struggle for a sense of control and dignity, for being seen as unique and competent individuals instead of being restricted to their illness (Lilja & Hellzen 2008). Others may accept their role as passive mental patients in order to avoid conflicts with staff and have better access to services (Ekeland & Bergem 2006).

Some argue that in the USA, the notion of recovery, while not largely accepted or understood by psychiatry or nursing, ‘has been unceremoniously dumped into the mainstream of clinical practice’ (Davidson et al. 2006a, p. XIX). US clinicians are concerned that promoting the notions of self-care, self-determination and choice can disguise the agenda of cutting services and costs without formulation of any feasible alternatives to existing services (Davidson et al. 2006b). In order to avoid such pitfalls, there is a need for more in-depth international studies exploring concepts and processes of recovery shared by service users across various contextual and situational factors.

The Irish Context

Because of the different economic, social and cultural contexts in which the individual resides, Irish persons with mental health problems may or may not share the same vision of recovery as those residing in the USA or the UK. In the absence of detailed in-depth studies of experiences of Irish service users it is impossible to completely refute the possibility (Popper 1963) that the Irish service-users may have a different conception of what it means to recover.

The concept of recovery is relatively new within the Irish context, and appeared in the Irish mental health policy documents only in 2005. Despite the emphasis on de-institutionalisation and recovery in the Irish mental health policy, community services in Ireland are still underdeveloped (Higgins 2008). Rehabilitation mental health services in Ireland had been largely associated with ad hoc ‘resettlement programmes’ for long-stay patients who resided in mental institutions for many years (Irish College of Psychiatrists 2007). Multidisciplinary teams consisting of psychologists, social workers, or occupational therapists are scarce (Irish College of Psychiatrists 2007). The service delivery is mostly medical-nursing with few alternatives to medication (Higgins 2008).

Mental health status in Ireland has been largely defined by the use of in-patient services and diagnosis, with the prevalence of biomedical model in psychiatry, nursing, and limited community services (Brennan 2004, Higgins et al. 2006, Irish College of Psychiatrists 2007). As elsewhere, in order to accommodate recovery within the Irish mental health practice, the concept of the second order change, or social inclusion and integration, has yet to be made compatible with, and as important as the concept of the first order change, or alleviation of symptoms.

A study involving residents of community accommodation provided by the public mental health services showed that the culture of institutionalisation still persisted, and the recovery approach to treatment and care had yet to be implemented within Irish community mental health services (Tedstone Doherty et al. 2007). As stated in A Vision for Change (Department of Health and Children 2006), the most recent blueprint for the Irish mental health policy, ‘Current service provision doesn’t address the broad needs of service users for social as well as clinical recovery. There is a need for a well-developed and shared philosophy of recovery-oriented care and of structured, person-centred, recovery-oriented programmes for service users with severe and enduring mental illness’ (p. 106).

To be successful, mental health services should be congruent with the local consumer representation of illness and recovery (Shorter 2006). We need to identify the underlying main concern and basic social processes of recovery, shared by different groups of persons with mental health problems both in Ireland and elsewhere. Such concerns and processes can only be explored via individual interviews, by asking open-ended questions in a simple neutral language, relatively clear of any medical, ideological, or political terminology.

The other crucial requirement is to carefully listen and try to understand what people with first hand experiences are saying about their recovery, and what their underlying expectations of recovery are. As Jacquelyn McCullough put it in her letter to the Editor, ‘It is time to redefine our core business and get back to talking with the people that we say we are caring for’ (McCullough 2008, p. 540). The importance of consumer perspectives on the factors that can promote or impede recovery has been highlighted by international studies (Happell 2008a). After all, the job of mental health services should be directed at meeting the needs of service users, as opposed to the service users meeting the needs of mental health practitioners or policy-makers (Happell 2008b).

Objectives

The aims of this study are to explore individual processes and desired outcomes of recovery from the point of view of persons with recurrent mental health problems, in order to build up a theoretical framework of recovering in an Irish context and inform specific recommendations for mental health services.

Materials and methods

In line with its theoretical objectives, the study was conceived as qualitative and open-ended, aiming at eliciting individual definitions and processes of recovery in order to facilitate in-depth understanding of what recovery means and how it happens from the point of view of persons with recurrent mental health problems in Ireland.

Due to the fact that that the concept of recovery had originally emerged from service users rather than service providers, it was decided to invite self-nominated persons with mental health problems who considered themselves in recovery and were willing to participate in the interviews. In addition, it was decided to limit the study to those who identified themselves as having experienced mental health problems more than once during at least two years, as this group was perceived by services as the most problematic and costly in terms of their recovery (Schinnar et al. 1990). For the purposes of theory-building, we were interested in the underlying concepts and processes of recovery shared by a broad group of persons with recurrent mental health problems (Glaser & Strauss 1967).

Therefore, the inclusion criteria for this study were persons who reported that they have experienced mental health problems more than once for a period of at least two years and considered themselves to be in improvement. Whereas it was anticipated that the majority of participants would have used mental health services at some stage of their experience, use of services was not part of the inclusion criteria for this study.

We selected a grounded theory (GT) approach as it offers the possibility of theory building (Glaser & Strauss 1967) and is sensitive to social context and culture (Strauss & Corbin 1998). Theory building involves exploration of how the emergent framework fits into the existing literature (Glaser 2001). Constant comparison, theoretical sampling and constant modification of the interview schedule in accordance with the emerging findings (Glaser 1978) facilitate coding and integration of the theoretical framework.

Individual open-ended interviews were chosen in favour of focus groups for two main reasons: 1) in order to elicit sufficient qualitative data for in-depth exploration and comparison of individual views and experiences; and 2) in order to ensure confidentiality of participation in the light of perceived stigma associated with mental illness. Irish service users consulted during the scoping stage of the study commented that individual interviews were preferable for a recovery study, as people may feel threatened to speak in-depth about sensitive individual experiences in a group.

To ensure equal coverage of issues related to service provision for future recommendations, at the end of the interviews all participants were asked to fill out a brief questionnaire where they stated their age, gender, educational, employment, and marital status, the nature of their mental health problems (diagnosis if known), the approximate duration of their experience with mental health problems in years, the use of various mental health services and peer support groups in the last 12 months and in the past, and their general satisfaction with the services and support provided to them over the years. The inclusion of information about diagnosis served descriptive rather than conceptual purpose. As the concept of recovery emerged from consumers with different diagnoses (Anthony 1993), we were aiming at capturing similarities rather than differences in the representation of recovery across diagnostic groups. However we were also open to any diagnostic differences in recovery definitions should they have emerged from the narratives.

The project was carried out in the area of two Irish counties and included participants of peer support groups in urban locations, and users of mental health services who attended day centres in suburban and rural areas. Day centres are part of public community services and are attended by users of diverse services, including users of inpatient and community residences facilities, and day care, day hospital, and rehabilitation services. The functions of day centres include provision of outpatient nursing care, administration of medication, participation in work and self-management skills programmes and other activities facilitating integration in the bigger community. The areas (urban, suburban and rural) were selected in order to facilitate maximum variation of the sample (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Maximum variation sample facilitates exploration of the underlying concepts and processes shared across different contexts and various groups of participants (Glaser & Strauss 1967).

Following Glaser’s recommendations, we decided not to resort to substantive reading on the emerging categories during fieldwork and analysis until the formulation of a preliminary theoretical framework of recovery (Glaser 2001). The codes described in this article emerged directly from the data.

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Board and the relevant mental health services authorities. The original interview schedule was drafted during consultations with service users and service providers and designed as open-ended and flexible, with a view of its further adjustment on the basis of concepts emerging from the interviews. Interviews started with an open-ended question: ‘So tell me about your experiences with mental health problems and recovering, anything that you think is important’. The views of participants on the desired outcomes of recovering were elicited by the prompts: ‘So what does recovery mean to you? How would you measure the success of your treatment and recovery?’ In order to elicit possible turning points towards recovery, participants were asked to describe, if they remembered, when and how their mental health had improved for the first time.

During the interviewing and analysis we tried to stay focussed on the underlying main concern of the participants and behaviours and processes aimed at resolving their main concern (Glaser & Strauss 1967). We constantly asked ourselves three GT questions (Glaser 1978): What is this data a study of? What category or property does this incident indicate? What is actually happening in the data?

The selected results presented here are based on the total sample of 15 interviewees recruited over the two stages of the study. The first author conducted all the interviews, which lasted for between 30 minutes and 1.5 hours, and which were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. All interviewees signed a written consent form prior to beginning of the interviews.

The majority of participants were recruited via peer support or community groups (n=9), whereas six were recruited via the mental health services. Among the primary diagnoses reported by the participants, one third (n=5) were those of schizophrenic illness and six of mood disorder (depression or bi-polar). Four participants noted that they been diagnosed with unspecified anxiety. The reported median duration of recurrent mental health problems of participants was 20.0 years ranging from two to 43 years.

The majority of interviewees were male (n=9) whereas over one third were female (n=6). The average age of the participants was 47.1 years. Most of the participants (n=12) lived in urban or suburban areas, whereas three lived in rural areas. Most of the participants (n=10) had used in-patient services at least once, whereas one third had never used in-patient services (n=5).

First stage of recruitment, interviewing and data analysis

Prior to conducting first six interviews, the authors delivered a presentation to mental health nurses and psychiatrists of the catchment area and answered questions about the aims and methods of the study. The first author then visited a day centre and a community residence facility located on the grounds of the hospital and spoke to the service users and staff about the aims and methods of the study. The information letter (see Appendix A) was distributed to the staff and service users. Persons willing to participate contacted the researcher directly in person or by telephone, and the time and place for the interviews was agreed. Six interviews with mental health service users were conducted during the first stage of the study.

The first six interviews took place in day centres located in suburban and rural areas of the catchment area of the hospital. All six interviewees had used in-patient mental health services in the past. Half of the interviewees reported that they had been diagnosed with a schizophrenic illness, two with depression, and one with bipolar disorder. The reported median duration of illness of participants was 21 years ranging from nine to 43 years. Four interviewees participated in peer support groups either in the last 12 months or in the past. Two participants considered such participation helpful whereas two did not.

The first author studied the transcripts and field notes of six interviews and performed line by line coding. The emergent themes were grouped under broader concepts and codes and constantly compared with similar output of participants (Glaser 1978). Open (Strauss & Corbin 1998), or substantive coding (Glaser & Strauss 1967) of the first six interviews yielded 305 in vivo codes. The codes were entered on an Excel spreadsheet and categorised into more abstract concepts. The sheet also documented the interview number and page of the transcripts from where the code originated. This sheet was being constantly updated and modified during the study.

The second author independently coded selected excerpts of the first six interviews containing definitions of recovery and the start of improvement. The two authors compared and discussed the results of coding and labelling and agreed on labels of 13 broader concepts falling into two main categories of definitions of recovery: getting rid of negative feelings, and acquiring positive feelings and actions.

The in vivo codes of giving up and fighting to get better emerged from the first six interviews and lead to further research questions. The following prompts were added to the original interview schedule:

Some of our previous interviewees mentioned that you had to fight to get better, and not to give up. Do you think it is important to fight for your recovery? Have you ever ‘fought’ to get better? How and when? What would you fight for, what would you fight against? What can motivate you to fight for your recovery?

What about ‘giving up’? Have you ever ‘given up’? When and how could it happen? Why? Have you seen other people who ‘gave up’? Where and when? How do you know that they ‘gave up’?

Following the questions arising from the findings, further sampling steps were formulated. The second stage of sampling aimed at recruiting three or more volunteers who did not use mental health services, were living in the community and were participating in peer support or advocacy groups. An attempt was made to include one or more volunteers who had never used mental health services, at least in-patient ones.

Second stage of recruitment, interviewing and data analysis

We contacted GROW (World Community Mental Health Movement) in Dublin via e-mail and arranged a meeting to discuss the nature of the study and potential participation of GROW members in the study. After the meeting the GROW representative distributed the information letter to potential participants who then contacted the researcher directly. The researchers also had a meeting with an Irish Advocacy Ireland (IAN) representative who distributed the information letter to IAN members, who then contacted the researcher directly.

Nine more interviews were carried out with six volunteers attending GROW, two IAN members, and one volunteer who independently found out about the on-going study on the internet and expressed his willingness to participate. Following volunteers’ preferences, one IAN peer advocate was interviewed in a private room in a Dublin university, and another in a cafeteria of a Dublin general hospital. Interview with a self-recruited person with recurrent mental health problems took place in the researchers’ office meeting room. Four interviews with members of GROW took place in the GROW Dublin office, whereas two other members of GROW were interviewed in the researchers’ office meeting room.

Among the primary diagnoses reported by participants, four reported being diagnosed with unspecified anxiety disorder, one third with depression (n=3), and two with schizophrenic illness. Although all of the volunteers had a lengthy experience with recurrent mental health problems (median was 20 years ranging from two to 42 years), only one person was using mental health services in the last 12 months. Also, five volunteers had never used in-patient services but had used outpatient services of psychiatrists, psychologists and counsellors in the past.

After completion of the next nine interviews, more coding was performed and combined with the results of the first stage of the analysis. The open codes were collapsed into 20 categories which are being further modified and compared with the new data.

Memo-writing is essential for a grounded theory study (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Memos are ‘written records of the analysis that may vary in form’ (Strauss & Corbin 1998) (p. 217) and may contain observations, codes, categories and theoretical notes. Two memos were created on the basis of emerging open codes pertaining to the process of recovery during the second stage of analysis: ‘giving up’ and ‘fighting’. Tentative axial dimensions of the open code ‘fighting to get better’ were drawn (Strauss & Corbin 1998) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tentative dimensions of the code ‘fighting to get better’

The selected findings of the second stage of analysis of the 15 interviews, related to definitions of recovery, turning points in recovering, and the codes of giving up and fighting to get better are presented below.

Results

Definitions of Recovery

Personal definitions of recovery fell into two broad areas: getting rid of negative feelings, such as anxiety, depression, or panic attacks; and acquiring positive feelings and actions, such as peace of mind, self-acceptance, sense of belonging, taking control, helping others, working, and being happy.

Peace of mind definitely, if I just had that one thing, peace of mind… It’s when I don’t have peace of mind I do get panic attacks; one thing I’ve noticed over the years is that they’re less and less common (1).

Acceptance of who I am, that I belong somewhere… When I grew up, for instance, I’ve never even had a sense of family, or a sense of value… that’s the kind of thing I have in my head at the moment, that I have a house somewhere I can go to and say ‘This is my family’, you know, that would be a big part, kind of, in recovering sense (9).

Definitions of recovery elicited from participants suggested that recovery was two-directional: 1) recovery from negative feelings, or symptoms, and 2) recovery of positive feelings and actions. Both of these directions were important and interrelated in the participants’ views on what constitutes recovery.

Turning Points in Recovering

Participants described some turning points as: being listened to, being accepted, making a conscious decision to get better, verbalising and overcoming feelings about their traumatic experiences, having a dialogue, and changing or reducing their medication.

Five people commented that their first improvement was associated with talking to peers. Peers treated each other equally, accepted persons as they were, listened without judging or labelling persons as ‘mental’, and conveyed a verbal or non-verbal message of willing to help:

I was terrified to sit down, because I was afraid that I’d fall off the chair, I was so nervous going in. The first impression of [peer group] was, they don’t think I’m mental, they don’t think I’m nuts, they said ‘Yeah, no problem, of course you can sit on the floor’. So I think the first thing that hit me was, here’s people who accept me for where I am, who I am, they don’t really care whether I want to stand on me head, you know, once I’m here, and they’re going to help me, you know (11).

Five participants reported that they initiated their recovery themselves, by making a conscious decision to get better. Some made this decision in in-patient units after they saw negative examples of other patients who did not want to recover: ‘I saw other people in hospital who did not want to recover, and I did not want to be like them’ (8).

Despite different personal circumstances surrounding turning points which led to recovery, an important shared component was the realisation that something needed to change, and developing self-determination for this change:

I can remember actually saying to myself, I was getting to the sort of stage where I couldn’t get out of bed, ‘I can’t go on with this anymore’… I got through my own stage then by myself, and actually my first big step towards recovery was, believe it or not, getting myself out of bed, talking myself out of bed. Now that sounds like a small step but it really was a major step for me, actually just to get out of bed (9).

Fighting to Get Better

We identified two interrelated but distinct processes of recovering: ‘fighting to get better’ and ‘giving up’. These two codes emerged from the first six interviews and were explored in subsequent nine interviews.

Fighting to get better started with finding one’s own motivation for recovery, and learning new ways of coping with the negative emotions. It was an on-going, day-to-day process which required a lot of energy and effort. Participants felt that it was crucial to have something or somebody in life to fight for.

Not to give up, to fight, I mean every day you have to fight, you’re fighting one thing or another but if you lose the battle, depression can take over your life. It can totally ruin you, if you let it, but find something in your life that you want to fight for, and it helps a great deal. I fought for my children, my grandchildren really (6).

Figure 1 represents preliminary dimensions of the code of fighting to get better.

As one can see from the left hand side of Figure 1, motivation, or reason for fighting can be positive external (fighting for something or somebody, e.g. qualifications, work, children, partners, sick relatives) or positive internal (peace of mind, happiness, being ordinary, being in control). Negative dimensions of fighting against, as shown on the right hand side of Figure 1, also include internal and external factors: fighting against fear, worry, depression, loss of control (negative internal), and social disability and exclusion, such as unemployment, stigma, and isolation (negative external):

I reckon trying to just be ordinary, and happy, you know, you just want to live an ordinary happy life, you’re not looking for, to move mountains, you know, you just want peace in your mind, have no more anxiety, no more depression, to be able to cope with the normal stresses of life (11).

Participants fought negative emotions by self-talk, talking to peers or professionals, taking medication, deep breathing, and even by playing poker in one’s mind. Motivation for recovery had to be self-sustained and reinstated on an on-going basis:

Oh you have to be very motivated to recover, you have to motivate yourself, you have to have a lot of willpower, you have to say to yourself, ‘Now I’m going to get better, I’m going to evolve; I’m going to get better’(5).

More than half of the interviewees (n=8) commented that talking to other people or professionals, sharing your problems and having advice helped to control negative emotions.

The doctor I go to is a very good doctor… because I go in and I’d say something and he’d say, ‘Did you try it, did you try it that way, or did you try it this way?’ And maybe I wouldn’t have thought of those things, and you find yourself trying to do this and that and it works, you know he’s very good (6).

Four participants were taking medication in order to prevent their relapse and keep their anxiety and depression at bay: ‘I just hope I don’t have another breakdown, that’s why I’m taking the medication’ (3).

One had to fight with negative emotions and learn how to control or stop them with the help from doctors, medication or with other alternative methods: ‘The deep breathing is very helpful, if you feel panic sweeping over you I just count to ten, do my deep breathing and I feel myself calming down’ (6).

Participants suggested further labels of the process of fighting, such as pushing oneself, taking control, making sense of previous experiences, and making an effort:

As to whether one has to fight, yes one has to make an effort, life requires effort and if one gives up, to despair or to hand it over to someone else as one can do by taking medication, unless one needs it, and that’s another debate… If one gives up on making the effort, one gives up living then basically, and so I would say yes, one has to fight, fight is a word that I wouldn’t be choosing myself, I would chose the word effort. There is an effort involved in living (14).

Despite the variety of labels of ‘fighting’ suggested by some participants, the concept itself was relevant to all participants and represented an active self-induced effort to get better, in terms of getting rid of negative feelings and acquiring positive feelings and actions. However some participants underlined that they needed support from other people to help them fight, as it was difficult to do it on one’s own:

[Some previous people were telling me it was very important to fight and not to give up on your recovery. Would it make sense to you?] You don’t like the ‘fight’ word, do you? But it’s true, it is true, I suppose you could use the word fight, you have to put up a fight, but you can’t do it on your own, you need all, you need people to help you fight, you just can’t just do it on your own, and fight, I’d say it would be very hard (11).

Giving up

The phenomenon of giving up was associated with accepting a passive stance of a chronic ‘mental patient’. Giving up often occurred after a person was told by service providers that they would need professional support and medication for the rest of their lives. The responsibility for own life and well-being was handed over to mental health professions or family members. Benefits of ‘giving up’ included the comforting feeling of being looked after or ‘waited upon’:

And it was so easy to go into the hospital and just, you know, your meals handed up to you, whereas at home the children were there, you know, your husband always wanting this and wanting that, and to go into the hospital and be waited on, it was just, you know, it never happened to me before, someone waiting on me you know. It was just so easy, it had been so easy to give up and say ‘Well this is it, I don’t want to go back out’ (6).

‘Giving up’ allowed a person to stop worrying about the future, as some problems such as affordability of a house may seem impossible to resolve: ‘I think I’ll still be in hospital because I can’t afford a house, and I haven’t concentration for work, and I’m sixty one anyway’(2).

Some drawbacks of giving up were losing all hope of recovery; accepting one’s inability to work, to support oneself and others, and to lead a ‘normal’ life in the community.

The concept of giving up was relevant to all 15 interviewees, who either reported that they had a period when they had given up, or saw other people who gave up:

Well they resigned themselves to having mental health problems for the rest of their lives, they resigned themselves to using mental health services for the rest of their lives, and they can’t seem to see outside of that, for whatever reason. So they’ve lost the struggle, lost the fight in some sense you know. It’s not to say they will not get it back or whatever, but at that point they seem to have given up or something (9).

’Giving up’ was also associated with the perceived lack of internal motivation for self-induced change, or courage to ‘fight’ to get better:

[How do you know that people ‘gave up’?] It’s like as if they want to stay where they are… [Why would they want to stay where they are?] Ah, because like, it takes time, you know, you have to give yourself time, and you have to have patience too as well, and you have to have courage, and character, and all that (12).

Discussion

The study adds perspectives of Irish persons with mental health problems to the previous international findings on recovery. Preliminary results indicate that there are more similarities than differences across cultures on consumer views on recovery. This study also adds to the previous literature by extending exploration of recovery beyond the use of services to facilitators and barriers of recovery in a broader community. This may help further analysis of shared underlying constituents of recovery which may help or impede recovery or long-term rehabilitation.

Some of the definitions of recovery included piece of mind, not worrying, and being able to work and socialise. Such concepts are similar to the elements of psychological well-being and positive mental health, such as self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, and growth (Ryff 1995). The final stage of growth is highlighted in the three-stage model of recovery (Andresen et al. 2003). Our preliminary findings suggest that constant effort aimed at positive transformation and growth may underlie the whole process of recovery.

Participants recalled that their turning points towards recovery occurred when they were being listened to, feeling accepted, when they could retell and overcome their traumatic experiences, made a conscious decision to get better, and changed or reduced their medication. Some of these turning points are similar to the steps or component processes described by previous studies, e.g. developing an explanatory framework for understanding the illness experience (Spaniol et al. 2002), and taking responsibility for recovery (Andresen et al. 2003).

Selected findings of our study support the previously reported correlation between the first order change (alleviation of symptoms) and the second order change (integration and inclusion) (Brown et al. 2008). Moreover, our findings indicate that the first order change, such as the alleviation of symptoms, or even treatment compliance may be fostered by the elements of the second order change, e.g., feeling accepted and developing own motivation to get better. Being listened to, being accepted and not being judged can become a turning point towards recovery. This finding may be considered by various mental health professionals as useful for initial and subsequent contacts with persons experiencing mental health problems.

Giving up and fighting for recovery

The code of fighting to get better was relevant to all participants of the current study and had elements of confrontation with the pessimistic prognosis, chronicity of their illness, deterministic attitudes of service providers, loss of control over their life, and social exclusion. The opposite category of fighting to get better, ‘giving up’, was associated with accepting the chronicity of the diagnosis, the passive identity of a ‘mental patient’, and handling over control to mental health service provision, medication or carers.

Whereas it is hard to generalise if fighting to get better was something initially inherent in a person or it developed gradually, some participants commented that fighting started with getting hope, energy and the belief that recovery was possible. In a few cases, fighting started as a negation or a revolt against being seen as a disease, or seeing other patients who gave up and not wanting to be like them. In other cases, friends, relatives and employment had positive influence on the development of the persons’ determination to get better.

‘Fighting spirit’ in oncology

The code of fighting to get better identified in this study is somehow similar to the concept of ‘fighting spirit’ emerging from studies of persons diagnosed with cancer (Morris et al. 1992). The concept of ‘fighting spirit’ in oncology contains four dimensions: a highly optimistic attitude; a search for more information about the illness; a wish to fight, defeat, or conquer cancer; and not being taken over by emotional distress (Greer et al. 1979). Persons with higher scores on the first three dimensions also scored lower on emotional distress. Moreover, compliance and the tendency to suppress negative emotions or anger were shown to lead to chronic helplessness when faced with the ‘finality’ of cancer diagnosis, and to influence prognosis (Temoshok 1987).

Seeing cancer as a severe and enduring threat of all aspects of life significantly reduced survival of patients (Morris et al. 1992). Lack of fighting spirit was associated with acceptance, fatalism, helplessness and negative views on the future summarised as ‘Life can never be good as it was before’ (p.113). Conversely, the attitude of patients with higher levels of fighting spirit was described as ‘I will live as I lived before, maybe better’ (p.112).

Previous studies have shown that recurrence-free survival in oncology was significantly longer among persons who reacted to a cancer diagnosis with attitudes of denial, or ‘fighting spirit,’ than among those who reacted with ‘stoic acceptance’, or hopelessness (Pettingale et al. 1985). A more confronting reaction to cancer diagnosis was associated with better emotional well-being, whereas both avoidance of thoughts, or feeling overwhelmed by thoughts about the illness was associated with anxiety or depression (Nordin & Glimelius 1998). Fighting spirit can represent the person’s intentionality, intrinsic motivation and may be an essential component of self-healing.

‘Fighting spirit’ in recovery from mental illness?

The emergent code of fighting to get better was associated not only with in-patient units or symptoms of illness, but also with the integration into the wider community (e.g. fighting for one’s family, work, belonging). Our findings show that this fight or struggle was not only directed against depression or anxiety, but most importantly, for finding one’s own place in the world and the ability to face daily challenges. Some of the reported fighting tools or ‘weapons’ were medication, talking, self-talk, and positive relationships. Both the individual internal, and environmental external factors seem to be equally important and interrelated in the process of recovery from mental illness (Onken et al. 2007).

The code of fighting to get better seemed to embrace both stages highlighted by Spaniol et al. (2002): ‘fighting with disability’ and fighting for life ‘beyond’ or despite the disability. Fighting for recovery from mental illness may be more complex and may require even more motivational effort than fighting with a physical chronic illness. As shown by some studies (Tedstone Doherty et al. 2007), deinstitutionalisation of Irish mental health services has been slow, and recovering persons with mental illness may require on-going acceptance and support on the part of the broader community.

The concept of fighting spirit may be a relevant construct for recovering from mental health problems. It can serve as a predictor of successful recovery, and therefore may be considered as a useful measure of potential of recovery and the need for development of intrinsic motivation to get better.

Can ‘giving up’ turn into ‘fighting?’ Fostering intrinsic motivation and self-determination

The concept of intrinsic motivation as opposed to controlled motivation is based on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan 1985) and learned helplessness theory (Abramson & Seligman 1978). Both theories are non-deterministic insomuch as they assume that humans are the source of action, and voluntary behaviours are inherent in life. Moreover, intrinsic motivation forms the energising basis for natural and spontaneous behavior. Helping persons to develop intrinsic motivation may be relevant for turning ‘giving up’ into ‘fighting’ to get better.

In self-determination theory, human behavior is described as resulting from intentionality, which refers to the conscious or spontaneous formulation of future behavior which this person will attempt to perform. Amotivation can be regarded as behavior not regulated by one’s intentionality, either due to a lack of self-confidence or some environmental barriers such as arbitrary control of authority.

If persons had been exposed to offensive, forcing or highly unpleasant events outside of their control in the past, they may acquire learned helplessness leading to cognitive and emotional difficulties, and amotivation. Such persons may exhibit impaired curiosity, lack of learning skills, and depressive mood. These properties are very close to the ones described by the participants as characteristic of persons who ‘gave up’ on their recovery.

Some of the previous experiences of the participants of the current study included violence, sexual abuse, bullying, parental neglect, parental alcohol abuse and other unpleasant or stressful phenomena. It can be argued that such unpleasant experiences in the past may have negatively affected their self-determination, intrinsic motivation, and decision-making: ‘If child abuse happened in your life you know, that terrible emotional crime, dreadful… I think only someone that’s been through it really understands how it feels, and how it can really paralyse you, you know (6)’.

According to self-determination theory, intrinsic motivation may initiate a wide spectrum of energising behaviors or internal processes and is thus the form of self-determination. Contrary to extrinsic or control-determined behavior, intrinsically motivated behavior is initiated by choices based on personal interests and goals. In order to support intrinsic motivation to ‘fight’, or make an effort to get better, it may be crucial for service providers to convey a message of acceptance and helpfulness. As suggested by the participants of the current study, the initial decision or desire to start fighting for one’s recovery had to come from within the person. However, support of others was essential too, in terms of encouraging people to take and maintain control of their own recovery.

Wu et al. provide therapeutic guidelines on how to facilitate intrinsic motivation in persons with mental illness (Wu et al. 2000). The first is to support client’s autonomy by acknowledging the client’s ability to make decisions and solve problems, and encouraging taking actions based on personal choice as opposed to expectations of others. The second guideline has to do with structuring therapy services, so that short-term therapeutic activities led to experiencing success, with a view of extending these activities in the future in accordance with the outcomes and the client’s wishes. Involvement of family carers into fostering clients’ intrinsic motivation outside therapeutic settings was also advised.

Fighting to get better may entail substantial and long-term effort on the part of persons with mental health problems. It may look too risky and painful for some persons, and their motivation for recovery may need constant reinforcement and enhancement. A lot of encouragement from peers, family and service providers may be needed. Mental health professionals may wish to discuss with service users internal and external motivators of their ‘fight’ for recovery. Such motivators can be included in treatment and rehabilitation plans, and further revised with service users.

Limitations

The selected findings of the study reported in this article are based on a relatively small number of interviews (n=15) and should be interpreted with caution.

We did not have direct control of recruitment procedures as some participants were invited to the study via representatives of peer support groups and mental health services. However distribution of information letters and clarification of specific selection criteria by the researchers may have helped to ensure consistency of recruitment procedures.

The researchers’ subjectivity and previous background may have influenced study design, data collection and the analysis. Reflexivity, joint coding and discussions between the researchers, and verification of identified concepts by further participants and in the previous literature may help to reduce influence of author background and improve theory building.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the interviewees for sharing their unique life experience with the researchers. We are also very grateful to the Irish GROW and IAN mental health organisations and the public mental health services for their help with the recruitment of study participants. Special thanks are also due to Mr Darren McCausland for his comments after reviewing this article, and the anonymous external reviewers.

This study is carried out as part of the Health Research Board (HRB) in-house research programme. The HRB’s in-house research is funded by the Department of Health and Children. No additional external funding was sought.

Appendix A: Information letter about the study

[HRB logo]

Date

Recovering from recurrent mental health problems

What does it mean to you?

Dear Sir/Madam,

The Health Research Board (HRB) is carrying out a study to find out what ‘recovery’ means for different people who have experienced recurrent mental health problems. ‘Recurrent mental health problems’ for our study means that a person has experienced mental health problems more than once over a period of two or more years. An example of recurrent mental illness could be serious depression or schizophrenia.

Please note that you do not have to be a user of mental health services in order to participate in this project. We are looking for any persons who have experienced mental health problems more than once over a period of two or more years prior to the study, consider themselves to be in improvement and feel relatively well to tell us about their experience in a confidential interview. If you take part in this study you are covered by an approved policy of insurance in the name of HRB.

What has this got to do with you?

We would like to hear about your personal experience of recovering from mental health problems, what difficulties you have had at different times, and what helped you to get through them. Such information will help to make recommendations to service providers and policy makers and combat stigma by letting the public know real stories about mental health difficulties and recovery.

How do you tell us about your experiences, needs and recovery?

You are invited to have a private interview with Yulia Kartalova-O’Doherty, who is a researcher. The interview will be completely anonymous, this means that no-one else will find out what you have said, and no personal information (e.g. personal names, addresses, organizations, etc) will be included in the study report. Please also note that participation in this study does not form part of your treatment. It is also entirelyvoluntary, so if you feel like stopping at any stage you can do so.

To be involved you need to contact us

If you want to find out more or are willing to help with this study, or even if you have questions or comments, please phone Yulia Kartalova-O’Doherty

Phone [number] between 9.30am and 5.30pm, Monday to Friday.

Phone [mobile number] at all other times

E-mail [e-mail address of researcher]

What will be involved in the interview?

The interview will take between 45 and 90 minutes.

It will be arranged in a place that suits you.

The information you share with us during the interview will be available to the researcher only and no identifying details will be disclosed.

If you know any other persons who have recurrent mental health problems and who might be interested in the study, please feel free to give them the contact details.

With your help, the findings of the study will be published and made available to the public. We appreciate your time and effort, your experience is very important to us.

Yours faithfully,

Yulia Kartalova-O’Doherty

Researcher

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The current copy of the Article was accepted for publication by the International Journal of Mental Health Nursing after peer reviews in June 2009. The final version of the Article was published online Jan 6 2010, 19 (3-15) DOI: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00636.x. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/123234637/PDFSTART. The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

Contributor Information

Yulia Kartalova-O’Doherty, Researcher at the Mental Health Research Unit (MHRU) of the Health Research Board (HRB), Dublin where this project was carried out at the address: 3rd floor, Knockmaun House, 42-47 Lower Mount Street, Dublin 2, Ireland

Donna Tedstone Doherty, Senior Researcher at the MHRU of the HRB

References

- Abramson L, Seligman M. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allott P, Loganathan L, Fulford K. Discovering hope for recovery. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2002;21:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37:586–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. A consideration of the social trajectory of psychiatric nursing in Ireland. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2004;11:497–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Rempfre M, Hamera E. Correlates of insider and outsider conceptualizations of recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008;32:23–31. doi: 10.2975/32.1.2008.23.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T. Recovery: Say what you mean and mean what you say. Journal of Mental Health. 2008;17:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Harding C, Spaniol L. Preface. In: Davidson L, Harding C, Spaniol L, editors. Recovery from Severe Mental Illnesses: Research Evidence and Implicaitons for Practice. Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; Boston: 2006a. pp. xix–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, O’Connell M, Tondora J, Styron T. The Top Ten Concerns About Recovery Encountered in Mental Health System Transformation. Psychiatric Services. 2006b;57:640–645. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.640. J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci E, Ryan R. The General Causality Orientation Scale: Self-determination in Personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 1985;19:109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Children . A Vision for Change: Report of the Expert Group on Mental Health Policy. The Stationery Office; Dublin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ekeland T, Bergem R. The negotiation of identity among people with mental illness in rural communities. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. The Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualisation Contrasted with Description. The Sociology Press; Mill Valley: CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of grounded theory. Aldline; Chicago: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Greer S, Morris T, Pettingale K. Psychological response to breast cancer: effect on outcome. Lancet. 1979;ii:785–878. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B. Determining the effectiveness of mental health services from a consumer perspective: Part 2: Barriers to recovery and principles for evaluations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008a;17:123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B. Who cares for whom? Re-examining the nurse-patient relationship. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008b;17:381–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzidimitriadou E. Political ideology, helping mechanisms and empowerment of mental health self-help/mutual aid groups. Community and Applied Social Psychology. 2002;12:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins A. A Recovery Approach within the Irish Mental Health Services: A Framework for Development. Mental Health Commission; Dublin: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins A, Barker P, Begley C. Iatrogenic sexual dysfunction and the protective withholding of informaiton: in whose best interest? Journal and Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing. 2006;13:437–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish College of Psychiatrists . How to set up rehabilitation and recovery services in Ireland: Guide for consultants in rehabilitaiton psychiatry produced by the Faculty of Rehabilitation and Social Psychiatry. Occasional Paper OP64. Irish College of Psychiatrists; Dublin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lilja L, Hellzen O. Former patients experience of psychiatric care: A qualitative investigation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008;17:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough J. Letter to the Editor. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008;17:450. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris T, Pettingale K, Haybittle J. Psychological Response to Cancer Diagnosis and Disease Outcome in Patients with Breast Cancer and Lymphoma. Psycho-Onocology. 1992;1:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence . Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care.Clinical Guideline 1. NICE; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin K, Glimelius B. Reactions to Gastrointestinal Cancer – Variation in Mental Adjustment and Emotional Well-Being Over Time in Patients with Different Prognoses. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:413–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(1998090)7:5<413::AID-PON318>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken S, Craig C, Ridgway P, Ralph R, Cook J. An Analysis of the Definitions and Elements of Recovery: A Review of the Literature. Psyhiartic Rehabilitation Journal. 2007;30:9–22. doi: 10.2975/31.1.2007.9.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettingale K, Morris T, Greer S, Haybitte J. Mental attitude to cancer: an additional prognostic factor. Lancet. 1985;i:750. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper K. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge & Kegan; London: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph R, Kidder K, Philips D. Can We Measure Recovery? A Compedium of Recovery and Recovery-Related Instruments (PN-43) The Evaluation Centre@HSRI; Cambridge, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon S, Healy B, Renouf N. Recovery from mental illness as an emergent concept and practice in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2007;53:108–122. doi: 10.1177/0020764006075018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Wolfson P. The rediscovery of recovery: open to all. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2004;10:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schinnar A, Rothbard A, Kanter R, Jung Y. An empirical literature review of definitions of severe and persistent mental illness. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1602–1608. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.12.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter E. The historical development of mental health services in Europe. In: Knapp M, Mcdaid D, Mossialos E, Thornicroft G, editors. Mental Health Policy and Practice Across Europe. Open University Press; London: 2006. pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol L, Wewiorsky N, Gagne C, Anthony W. The process of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone Doherty D, Walsh D, Moran R. Happy living here…A Survey and evaluation of community residential mental health services in Ireland. Mental Health Commission; Dublin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Temoshok L. Personality, coping style, emotion, and cancer: towards an integrative model. Cancer Surveys. 1987;iii:545–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooth B, Kalayanasundaram V, Glover H, Momenzadah S. Factors consumers identify as important to recovery from schizophrenia. Australasian Psychiatry. 2003;11:S70–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Chen S, Grossman J. Facilitating Intrinsic Motivation in Clients with Mental Illness. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2000;16:1–14. [Google Scholar]