Game shows are one of the most popular and enduring genres in television culture. Yet why we possess an inherent tendency to enjoy seeing unrelated strangers win in the absence of personal economic gain is unclear (1). One explanation is that game show organizers use contestants who have similarities to the viewing population, thereby kindling their likeability, familiarity, and kin-motivated responses (e.g. pro-social behaviour; 1, 2). Social-cognitive accounts posit that to simulate another's internal states successfully, we must deem ourselves as similar to the target person (3). We test two predictions: seeing a socially desirable contestant win will modulate neural systems associated with reward; and that this rewarding experience is further influenced by perceived similarity to a contestant (i.e. similar attitudes and values).

Volunteers first viewed films of two confederate contestants answering questions about personal, social and ethical issues. These contestants expressed themselves in either a socially desirable (SD [i.e. empathetic]) or socially undesirable manner (SU [i.e. inappropriate values; SOM). To check that this social judgment manipulation worked, volunteers performed a likeableness trait rating task (4). Positive traits scores were higher for the SD contestant, while negative traits were significantly higher for the SU contestant (F = 107.9, P < 0.0005; Fig. 1A). Next, volunteers underwent functional MRI scanning while they viewed the SD and SU contestants playing a game, where they made decisions as to whether an unseen card would be higher or lower than a second unseen card (5). A correct decision resulted in the contestant winning £5 (SOM). The number of wins and probabilities of winning were identical across contestants. After volunteers watched the contestants play, they played the game for themselves (SOM).

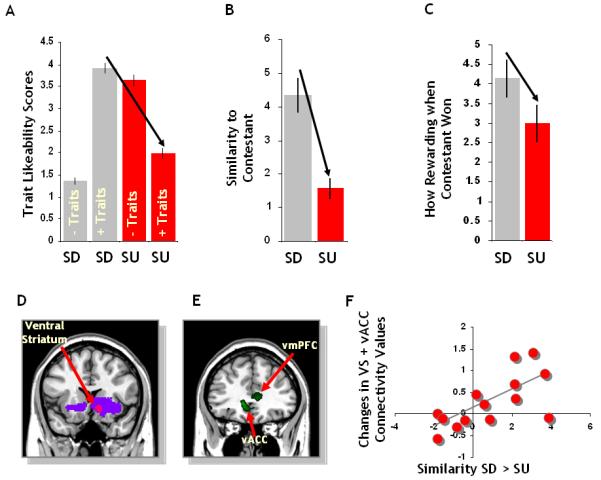

Fig. 1.

(A) Results from the trait likeability ratings showing the SD and SU contestant scores for positive and negative trait attributions. (B) Volunteers perceived themselves as significantly more similar to the SD contestant and (C) found it more rewarding when seeing the SD contestant win. (D) Significant activity associated with self-win (purple) and correlation between how rewarding it was to see the SD > SU win (pink). (E) Correlation between similarity, vACC and vmPFC activity and (F) psychophysiological interaction showing connectivity values (i.e., connectivity during SD winning - connectivity during SU winning) and individual scores of similarity (P = 0.043 small volume corrected).

Subjective ratings acquired after the experiment showed that volunteers perceived themselves to be more similar to, and in agreement with, the SD contestant (Fig. 1B), as well as finding it more rewarding to see them win (Fig. 1C; all t-tests: P < 0.05; SOM). Likewise, correlations were found between similarity and agreeableness, positive likeableness scores and how rewarding it was to see the SD contestant win. Both empathy and perspective taking scores (SOM) correlated with similarity to the SD contestant (all Pearson's: P < 0.05; SOM). No sex differences were found for similarity to the SD and SU contestants (see SOM for additional results).

For the brain imaging data, we first examined the correlation between how rewarding the volunteers found it when observing the SD > SU contestant winning (SOM). We found a significant increase in ventral striatum (VS) activity, a region also active when the volunteers themselves won while playing the game (Fig. 1 D; see SOM for additional analysis) and known to be involved in the experience of reward and elation (6). We next correlated perceived similarity scores for the SD > SU contestant win, which resulted in elevated ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity (vACC; Fig. 1 E). Although social psychological research shows that likeability and similarity are closely correlated, subtraction of the likeability ratings from the similarity ratings also resulted in significantly more vACC activity (Fig 2. F), supporting this regions putative role in self-other similarity (7, see SOM).

We next tested if the relationship between the VS and vACC was influenced by perceived similarity. We used psychophysiological interaction to examine connectivity between the VS and the vACC (using an independent VS seed from the self-play condition). We saw a significant positive relationship between similarity and connectivity between these two regions for the SD > SU contestant win contrast (Fig. 1F). No such modulation was found for likeability ratings (SOM). Given the vACC's uni-directional projections to the VS, the vACC may modulate positive feelings in situations relevant to the self (7).

Until now, studies of the neural representation of others' mental states have been concerned with negative emotions (e.g. empathy for pain). Here we show that similar mechanisms transfer to positive experiences such that observing a SD contestant win increases both subjective and neural responses in vicarious reward. Such vicarious reward increases with perceived similarity and vACC activity - a region implicated in emotion and relevance to self (3, 8). While other social preferences (e.g. fairness)(9) are likely to play a role in vicarious reward, our results support a proximate neurobiological mechanism possibly linked to kin-selection mechanisms where pro-social behavior extends to unrelated strangers (2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Ewbank, Rik Henson, Jack Rogers and Emma Hill for their help. This work was conducted at the Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit and supported by the Medical Research Council.

References and Notes

- 1.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. Nature. 2003;425:785. doi: 10.1038/nature02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JH, Schaller M. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2005;26:158–170. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell JP, Macrae CN, Banaji MR. Neuron. 2006;50:655. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson NH. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968;9:272–279. doi: 10.1037/h0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preuschoff K, Bossaerts P, Quartz SR. Neuron. 2006;51:381. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mobbs D, et al. Neuron. 2003;40:1041. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moran JM, et al. J. Cog Neurosci. 2006;18:1586. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Völlm BA, et al. Neuroimage. 2006;29:90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer T, et al. Nature. 2006;439:466–469. doi: 10.1038/nature04271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.