Abstract

Most studies of animal personality attribute personality to genetic traits. But a recent study by Magnhagen and Staffan (Behav Ecol Sociobiol 57:295–303, 2005) on young perch in small groups showed that boldness, a central personality trait, is also shaped by social interactions and by previous experience. The authors measured boldness by recording the duration that an individual spent near a predator and the speed with which it fed there. They found that duration near the predator increased over time and was higher the higher the average boldness of other group members. In addition, the feeding rate of shy individuals was reduced if other members of the same group were bold. The authors supposed that these behavioral dynamics were caused by genetic differences, social interactions, and habituation to the predator. However, they did not quantify exactly how this could happen. In the present study, we therefore use an agent-based model to investigate whether these three factors may explain the empirical findings. We choose an agent-based model because this type of model is especially suited to study the relation between behavior at an individual level and behavioral dynamics at a group level. In our model, individuals were either hiding in vegetation or feeding near a predator, whereby their behavior was affected by habituation and by two social mechanisms: social facilitation to approach the predator and competition over food. We show that even if we start the model with identical individuals, these three mechanisms were sufficient to reproduce the behavioral dynamics of the empirical study, including the consistent differences among individuals. Moreover, if we start the model with individuals that already differ in boldness, the behavioral dynamics produced remained the same. Our results indicate the importance of previous experience and social interactions when studying animal personality empirically.

Keywords: Personality, Boldness, Agent-based model, Social influences

Introduction

Empirical biologists have often noted that, like humans, animals differ consistently from each other in their behavior. Such individual variation has been labeled ‘personality’, ‘temperament’, ‘behavioral syndromes’, or ‘coping styles’ (reviewed in Groothuis and Carere 2005). In the last few years, interest in animal personality has surged. Though there is some discussion about how personality should be defined and measured, most scientists agree that individuals differ in personality when they behave consistently across time or across context. Consistency across time implies that differences between individuals in behavior, such as boldness towards a predator, are stable across time. Consistency across context means that the ranking of an individual within a group in one context, e.g., aggression, is correlated to its ranking in another context, e.g., exploration (reviewed in Sih and Bell 2008).

Currently, the mechanisms that shape personality are being extensively studied. It has been shown that a significant part of differences among individuals can be explained by additive genetic variation (reviewed in van Oers et al. 2005a) and that the heritability of personality traits lies around 0.4 (van Oers et al. 2005a). Therefore, there is much room for other processes to shape personality traits. Little is known about these processes. Several studies show the importance of experience with conspecifics: in studies of human personality, social conditions, such as the financial situation or the composition of a family during childhood, have been found to influence personality (reviewed in Hartup and Vanlieshout 1995). As for studies of animal personality, experiences with conspecifics altered the boldness in rainbow trout (Frost et al. 2007), and the level of food competition early in life affected the strength of the correlation between aggression and exploration in great tits (Carere et al. 2005a). Interesting is also the study by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005), which showed that in groups of perch, the boldness of an individual was affected by those of the other members of its group: the tendency of individuals to approach and feed near a predator was higher, the higher the tendency of the other group members. Furthermore, the feeding rate of individuals with low tendencies to approach the predator was especially low if other group members had high tendencies. But approaching and feeding near the predator were not only affected by social influences: the tendency of individuals to feed near a predator increased over time, and individuals were, to some extent, consistent in their behavior even after they had been regrouped with unfamiliar individuals of similar boldness.

The authors supposed that these behavioral dynamics were caused by social interactions, habituation to the environment and genetic differences. However, to be able to understand to what extent the combined effects of these processes can explain the results, a model is required. The aim of the present study has been to build such a model. We use a model with a high potential of self-organization through self-reinforcing effects, because our approach has already been shown to lead to new insights into the structure of personality (Hemelrijk and Wantia 2005). In this model, we replicated the experiment by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005) and we investigated the behavioral dynamics that emerged if individuals interacted with their environment in three ways: they habituated to the predator, were socially facilitated by each other to approach it, and they competed over food. We studied habituation because it was suggested by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005) and has been observed in many different species (reviewed in Shettleworth 1998).

We assumed social facilitation was occurring because in the study by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005), the time that individuals spent near a predator had been positively correlated to that of other group members, and because this mechanism has been observed in many species, including guppies (Laland and Williams 1997), three-spined sticklebacks (Krause 1992), rats (Gardner and Engel 1971), and monkeys (Harlow and Yudin 1933).

We added competition because some of the individuals in the study by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005) approached the predator, but did not feed near it. Thus, leading to the hypothesis that other group members may have prevented them from doing so. We added competition in such a way that an individual that arrived at the food first (a prior resident) had a competitive advantage over others that came later. We chose this form of competition because it is common in many fish species (see Kokko et al. 2006).

By testing these three mechanisms in all possible combinations, we established whether they were all needed to explain the empirical findings. We quantified the consistency of differences among individuals using the empirical measure for consistency called repeatability (Lessells and Boag 1987). This measure compares the variation in behavior of a single individual to the differences in behavior between individuals. Like in empirical studies, we measured the repeatability in isolated individuals (reviewed in Bell et al. 2009). To study the role of pre-existing differences reflecting, for instance, genetic differences or differences in previous experience, we ran the model both with individuals that started with identical tendencies to approach the predator and with individuals that differed in this tendency.

In sum, we studied whether habituation, social facilitation, and competition can account for the development of individual differences in boldness and for the dependence of these differences on the boldness of other group members as described by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005).

Methods

The model

The model is agent-based. It was programmed in C++, using Microsoft Visual Studio 2005. Default parameter values are given in Table 1. Like in the study by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005), we modeled 16 aquaria, each of which contained four individuals and two areas: a vegetated area and an area near the predator with food (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Default parameter values used in the model

| Parameter | Values | Description |

|---|---|---|

| initFood | 60 | Number of food items at the start of each day |

| approachTend | 0-1 | Tendency of an individual to approach the predator |

| initApproachTend | 0.05a,c, 0.03b, 0.5d, 0.02e | Initial tendency to approach the predator |

| habWeight | 0.8a,b,c,e, 0.3f | Weight for increase in tendency to approach the predator, after successful foraging |

| sfWeight | 3.00b, 2.00d, 1.00e,f | Weight for increase in probability to approach the predator, caused by social facilitation |

| compWeight | 2.00c, 3.00d,1.00e,f | Weight for decrease in maxIntake, caused by prior residence |

| maxIntake | 4 | Maximum number of food items that an individual can eat during one time unit |

| minInitApproachTend | 0.02f | The minimum initial tendency to approach the predator |

| maxInitApproachTend | 0.1f | The maximum initial tendency to approach the predator |

| boldThreshold | 0.8 | If mean time units spent near the predator is greater than or equal to this value, individual is bold |

| shyThreshold | 0.6 | if mean time units spent near the predator less than to this value, individual is shy |

Parameters values for a model with:

aHabituation

bHabituation and social facilitation

cHabituation and prior residence

dSocial facilitation and prior residence

eHabituation, social facilitation, and prior residence

fHabituation, social facilitation, prior residence, and initial variation

If a single value is given, the same parameter value is used for all models

Fig. 1.

Setup of the modeled aquarium; it was divided in a ‘vegetated area’ and an ‘area near the predator’ which contained food

Experimental setup

The model represented the experiment by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005). In this experiment, the authors observed wild-caught fish in 16 aquaria during three subsequent days. Each aquarium contained four young-of-the-year perch and one adult perch representing the predator. Each day, the authors recorded during 10 min how much food each individual ate, and they noted its position once every minute. They distinguished between ‘bold’, ‘shy’, and ‘intermediate’ individuals as follows: if an individual had spent on average less than 60% of the time near the predator and had eaten less than ten food items per day it was classified as ‘shy’; if it had spent 60% or more but less than 80% of the time near the predator and had eaten more than ten food items per day it was classified as ‘intermediate’, and if it had spent 80% or more of the time near the predator and had eaten more than ten food items per day it was classified as ‘bold’. The individuals were then regrouped so that new groups all consisted of four individuals with the same personality type. The authors avoided placing individuals together that had been in the same group before. Finally, they observed the individuals for another 3 days.

We followed the same procedure in the model, except for the method to distinguish between personality types: individuals were classified according to time spent near the predator by the same thresholds as in the empirical data, but the individual’s feeding rate was not taken into account. Feeding rate was omitted because it was strongly correlated to time spent near the predator and therefore hardly affected the boldness of an individual.

To determine the repeatability of differences among individuals, we tested them when isolated in the presence of abundant food.

Timing regime

One run consisted of 6 days and 1 day consisted of ten time units. Each day, the individuals started in the vegetated area and the food in the area near the predator was set to maxFood (Table 1). Each time unit, an individual could approach the predator and feed in the area near it as long as there was food available. If no food remained the individuals stayed in the vegetation until the next day.

Behavioral rules

At the start of each run, the tendency of an individual to approach the predator (Table 1 approachTend) was set to initApproachTend (Table 1). Each time unit approachTend was compared to a random number between 0 and 1; and if higher than this random number, the individual approached the predator:

|

In the area near the predator, an individual tried to feed. Feeding rate was given by a random number between 0 and maxIntake (Table 1).

|

We studied how the mean number of time units that an individual spent near the predator and number of food items that it consumed were affected by three causes, namely: habituation to the predator, social facilitation to approach it, and competition by prior residence. Habituation to the predator was modeled by increasing an individual’s tendency to approach the predator after it had successfully fed near it:

|

The parameter habWeight (Table 1) determined the steepness of the learning curve where an increase in habWeight leads to a steeper learning curve.

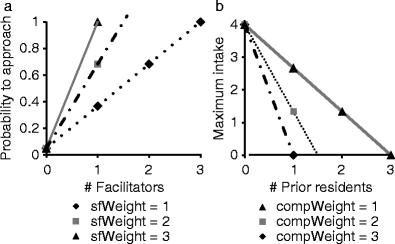

We modeled social facilitation as a linear increase in probability to approach the predator (approachProb) with the proportion of companions that were located near the predator:

|

The parameter sfWeight (Table 1) determined how strongly each additional group member near the predator increased the probability to approach it (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The effect of social facilitation on the behavior of an individual with an initApproachTend of 0.05: the probability to approach the predator increased with the number of group members already near the predator (a) and the effect of competition by prior residence on the feeding rate of an individual with a maxIntake of 4; the maximum intake per time unit decreased with the number of prior residents (b)

Competition by prior residence implies that individuals which arrive first have a competitive advantage over individuals that arrive later. This was modeled by a linear decrease of the maximum food intake of an individual with the number of prior residents. Here, prior residents were group members that arrived in the area near the predator earlier than the individual itself.

|

The parameter compWeight (Table 1) determined how strongly each additional prior resident decreased the maximum intake of an individual (Fig. 2).

We also ran the model with individuals that differed in their initial tendency to approach the predator. Here, each individual’s initApproachTend was drawn from a uniform distribution between minInitApproachTend and maxInitApproachTend (Table 1):

|

Parameterization

The parameters habWeight, sfWeight, compWeight, minInitApproachTend, and maxInitApproachTend were always set in such a way that approximately one-third of the individuals became ‘bold’, one-third became ‘shy’, and one-third became ‘intermediate’ so that this aspect of the model resembled the empirical data. This condition caused values of sfWeight and compWeight to range between 1 and 3 (Table 1).

Measurements and data analysis

To analyze the results of the model, we used similar methods as the empirical study. To quantify the differences among individuals in time spent near the predator and in feeding rate and the development of these differences over time, we used the coefficient of variation. To analyze the influence of other group members on the behavior of an individual, we correlated the time that an individual spent near the predator and its feeding rate to that of the other members of its group using a Spearman rank correlation. In addition, we determined the proportion of groups of which all members had the same personality type (the single-type groups) and compared this with the empirical data using a Fisher’s exact test. Like in the empirical data, we ran the model with 16 groups, except when comparing group composition using the Fisher’s exact test to obtain sufficient power for this test we ran the model with 64 groups. We measured time spent near the predator as the number of time units that an individual spent near the predator, averaged over 3 days, and the feeding rate as the number of food items that an individual ate, also averaged over 3 days.

To quantify the consistency of differences among individuals in time spent near the predator, we calculated the repeatability according to Lessells and Boag (1987). This is a different measure for consistency than used in the empirical study, but we chose it because it is the standard measure for consistency in studies of behavioral syndromes. It is based on the variance in time spent near the predator between individuals relative to that within individuals. We obtained these variances by running an analysis of variance test in which we entered ‘time spent near the predator’ as the response variable and ‘individual’ as a fixed factor. We calculated the repeatability both for individuals that initially differed in tendency to approach the predator and for individuals that did not. All statistical tests were conducted using R and two-tailed tests were used throughout. Differences among statistics were considered significant at α = 0.05.

Results

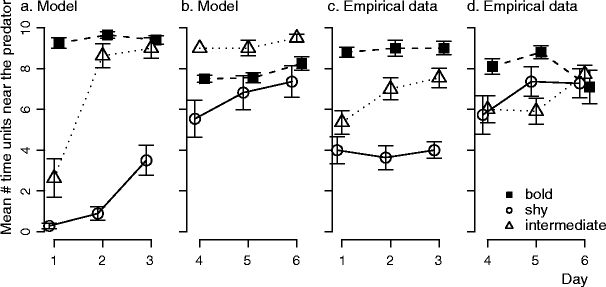

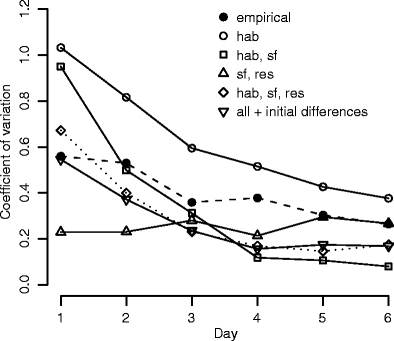

If individuals started with identical tendencies to approach the predator, and their behavior was only affected by habituation (parameter settings: Table 1, model a) large differences arose among individuals in time spent near the predator and in feeding rate, so that individuals could be classified as ‘bold’, ‘shy’, and ‘intermediate’ (Fig. 3). Over time, the boldness of shy and intermediate individuals increased (Fig. 3) so that differences between personality types became smaller (Fig. 4: hab). A similar trend occurred in the empirical data, though differences among individuals decreased more slowly (Figs. 3, 4: empirical). After individuals were regrouped according to personality type, members of ‘bold’ groups behaved less ‘bold’ (Fig. 3). This happened for the same reason as in the empirical data: because food shortage arose in groups containing only ‘bold’ individuals. Prior to regrouping, ‘bold’ group members could feed all day because ‘shy’ and ‘intermediate’ group members fed little (time unit at which food ran out:  , N = 14). But after regrouping, all members of ‘bold’ groups approached the predator and fed so that the food ran out sooner (time unit at which food ran out:

, N = 14). But after regrouping, all members of ‘bold’ groups approached the predator and fed so that the food ran out sooner (time unit at which food ran out:  , N = 11), after which individuals no longer left the vegetation.

, N = 11), after which individuals no longer left the vegetation.

Fig. 3.

Time spent near the predator of individuals in mixed groups, a, c before individuals were regrouped, and b, d after they were regrouped. Results from a model with habituation (a, b) and from Magnhagen and Staffan (2005) (c, d)

Fig. 4.

Coefficient of variation of time spent near the predator of all individuals

However, there were several differences between the results of our model and the empirical data; in the model, the time that an individual spent near the predator was negatively correlated instead of positively correlated with that of its companions (model, Spearman rank, r s = −0.30, N = 64, P = 0.020; empirical, r s = 0.69, N = 64, P = 0.000), and there were far fewer single type groups (Fisher’s exact, N = 64, P = 0.005).

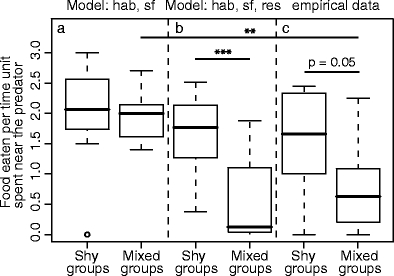

Adding social facilitation to the model (parameter settings: Table 1, model b) caused the time that an individual spent near the predator to be positively correlated with that of its companions (model, Spearman rank, r s = 0.76, N = 64, P = 0.000). This correlation arose because individuals were stimulated to leave the vegetated area because others were located near the predator. Consequently, the number of single type groups was similar to the empirical data (Fisher’s exact, N = 64, P = 0.26). Like in the model with only habituation, large differences in behavior appeared during the first day, which decreased thereafter (Fig. 4: hab, sf). However, in the model, the feeding rate of an individual was positively correlated with that of the other group members in contrast to the empirical data (model, Spearman rank, r s = 0.52, N = 64, P = 0.000; empirical, r s = -0.16, N = 64, P = 0.19). In addition, in the empirical data, shy individuals in mixed groups fed less fast when near the predator than shy individuals in shy groups, but this was not true for the model (Fig. 5). Thus, the match was not complete.

Fig. 5.

Average number of food items eaten during each time step spent near the predator of shy individuals in shy groups, and shy individuals in mixed groups. Results from a model with habituation and social facilitation (a), a model with habituation, social facilitation, and prior residence (b), and from Magnhagen and Staffan (2005) (c). Boxes represent median ± quartile. Asterisk indicates significant differences (Mann-Whitney U test). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Subsequently, we added competition because the reduced feeding rates of shy individuals in mixed groups suggested that bold group members prevented shy ones from feeding. After adding competition by prior residence (parameter settings: Table 1, model e), the results of the model appeared to resemble the empirical data in all aspects; the coefficient of variation of time spent near the predator decreased over subsequent measurement days (Fig. 4: hab, sf, res), there was a positive correlation in time spent near the predator between an individual and the other members of its group (Spearman rank, r s = 0.47, N = 64, P = 0.000), such a correlation was absent in feeding rate (r s = 0.01, N = 64, P = 0.92), the number of single type groups did not differ significantly from the empirical data (Fisher’s exact, N = 64, P = 0.56), and shy individuals in mixed groups fed more slowly than shy individuals in shy groups (Fig. 5).

By testing the effects of the three mechanisms—habituation to the predator, social facilitation, and competition by prior residence—in all possible combinations, we discovered that all three were required to reproduce the empirical data: without social facilitation, the positive correlation among group members in time spent near the predator was absent (Spearman rank, r s = −0.29, N = 64, P = 0.020). Without habituation, the coefficient of variation did not decrease over time (Fig. 4: sf, res). The results of the model were not affected if we started the model with individuals that differed in their initial tendency to approach the predator (coefficient of variation of time spent near the predator: Fig. 4, all + initial differences; correlation in time spent near the predator: Spearman rank, r s = 0.46, N = 64, P = 0.000; correlation in feeding rate: r s = 0.16, N = 64, P = 0.75; difference between model and empirical data in number of single-type groups: Fisher’s exact, N = 64, P = 0.73), although in this case, the degree of habituation by feeding near the predator had to be reduced to maintain the resemblance to the empirical data (parameter settings: Table 1, model f)).

If individuals with different initial tendencies to approach the predator were tested when isolated, differences among them were highly consistent ( , number of runs = 12, number of individuals per run = 32). This consistency was similar if individuals started with identical tendencies (Mann-Whitney, U = 77, P = 0.80, number of runs = 12, number of individuals per run = 32).

, number of runs = 12, number of individuals per run = 32). This consistency was similar if individuals started with identical tendencies (Mann-Whitney, U = 77, P = 0.80, number of runs = 12, number of individuals per run = 32).

Sensitivity analysis

To test the sensitivity of the model results to parameter changes, we systematically varied habWeight, sfWeight, and compWeight (Table 2). For each combination of parameter values, we determined whether (1) the model produced all three personality types in considerable amounts, (2) a correlation among group members in time spent near the predator was present, and (3) a correlation among group members in feeding rate was absent. We varied one parameter at a time while keeping the other two at default values. We found that if habWeight was 0.6 or above, all three personality types were present in considerable numbers (Table 2). The value of habWeight did not affect the correlation among group members in time spent near the predator, which was always present. The correlation in feeding rate was absent only if the value of habWeight was 0.6 or above. The reason for this is that habituation to the predator generated differences among individuals so that in some groups some individuals became prior residents. These prior residents disrupted the correlation in feeding rate because they prevented other group members from feeding. The value of sfWeight had no clear effect on the relative proportions of the three personality types, except when it was 0; in that case, most individuals were ‘shy’. If sfWeight was 0.5 or above, the correlation among group members in time spent near the predator was present, and if it was 1 or below, the correlation among group members in feeding rate was absent. The value of compWeight affected neither the relative proportions of the three personality types nor the correlation in time spent near the predator. However, only if compWeight was higher than 0.5 the correlation among group members in feeding rate was absent.

Table 2.

Effects of different parameter values of habWeight, sfWeight, and compWeight on three measures

| habWeight, sfWeight, and compWeight | Percentage of bold, shy, and intermediate | Correlation among group members | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent near the predatora | Feeding rateb | ||||

| Rho | P | Rho | P | ||

| habWeight | |||||

| 1 | 50, 16, 34 | 0.4** | −0.067(NS) | ||

| 0.8 | 44, 22, 34 | 0.474** | 0.012(NS) | ||

| 0.6 | 58, 13, 30 | 0.588** | 0.049(NS) | ||

| 0.4 | 8, 22, 70 | 0.862** | 0.547** | ||

| 0.2 | 0, 8, 92 | 0.906** | 0.793** | ||

| 0 | 0, 0, 100 | 0.825** | 0.59** | ||

| sfWeight | |||||

| 2 | 31, 27, 42 | 0.847** | 0.378* | ||

| 1.5 | 25, 36, 39 | 0.781** | 0.394** | ||

| 1 | 44, 22, 34 | 0.474** | 0.012(NS) | ||

| 0.5 | 28, 33, 39 | 0.42** | 0.14(NS) | ||

| 0 | 19, 8, 73 | 0.145(NS) | −0.057(NS) | ||

| compWeight | |||||

| 2 | 36, 25, 39 | 0.625** | 0.13(NS) | ||

| 1.5 | 44, 22, 34 | 0.551** | 0.201(NS) | ||

| 1 | 44, 22, 34 | 0.474** | 0.012(NS) | ||

| 0.5 | 17, 61, 22 | 0.788** | 0.384* | ||

| 0 | 14, 45, 41 | 0.835** | 0.689** | ||

Asterisk indicates a significant correlation: *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001. NS indicates that a correlation was not significant. One parameter is varied at a time, while the other two are kept at default values. The default values of habWeight, sfWeight, and compWeight are 0.8, 1.0, and 1.0, respectively

aThe Spearman rank correlation in time spent near the predator between an individual and the other members of its group

bThis correlation in feeding rate between an individual and the other members of its group

Discussion

Our model uses three mechanisms to explain the development of boldness in a social context as observed by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005). These mechanisms are habituation to the predator, social facilitation among group members to approach this predator, and competition over food. To reproduce the behavioral dynamics in the empirical data, all three mechanisms were required. Furthermore, behavioral dynamics were unaffected by the presence of initial differences among individuals in tendency to approach the predator.

Habituation to the predator gave rise to large differences among individuals in time spent near the predator. These arose because feeding near the predator was self-reinforcing; by chance, some individuals approached the predator and fed near it before others. These individuals habituated which meant that their tendency to approach was slightly increased so that they quickly fed near the predator again, after which, their tendency to approach was again increased. This led to a rapid increase in feeding rate and time spent near the predator so that these individuals became bold. Over time, differences among individuals decreased again for two reasons: the first reason is that shy individuals also habituated to the predator. The second reason is that after regrouping, the average time spent near the predator and feeding rate of bold individuals decreased due to food shortage in the bold groups.

If habituation to the predator was the only mechanism that affected behavior, group members behaved independently from each other so that single type groups rarely appeared. But if group members were also facilitated by each other to approach the predator, they became more alike both in time spent near the predator and in feeding rate. This gave rise to a positive correlation between the behavior of an individual and that of other members of its group and led to single type groups. Like in the empirical data, single-type groups rarely consisted of ‘intermediate’ individuals. The reason for this is that the self-reinforcing effect of feeding near the predator caused an individual to behave ‘intermediate’ only for a short time. Therefore, it was unlikely that four individuals in one group behaved ‘intermediate’ simultaneously.

However, social facilitation also caused a positive correlation in feeding rate among group members, while this was not observed in the empirical study. The model shows that this can be explained by the effect of competition in the form of prior residence, which made bold group members prevent shy ones from feeding. In sum, differences among individuals arose by accidental differences in habituation, were maintained by competition, but diminished by social facilitation.

Some effects of the mechanisms used in our model have been described in previous theoretical work. In our model, habituation to the predator resulted in a positive feedback between feeding near the predator and approaching it. Positive feedback loops are known to give rise to differences among individuals; for instance, large differences in dominance ranking arose among individuals if winning a dominance interaction was self-reinforcing (Hemelrijk and Wantia 2005). In our model, competition maintained differences in boldness among individuals. Similarly, it has been shown previously, that feedback between spatial structure and dominance interactions maintained differences among individuals in dominance ranking and in other aspects of behavior (Hemelrijk and Wantia 2005) and exploitation competition stabilized differences in diet among groups of individuals (Van der Post and Hogeweg 2008).

The combined effects of habituation to the predator, social facilitation to approach it, and competition over food appeared to reproduce and therefore explain the behavioral dynamics described in the empirical data of Magnhagen and Staffan (2005). We may ask whether these mechanisms also play a role in the shaping of personality traits as observed in other empirical studies. There are hardly any empirical studies on the effect of social context on personality development. However, a recent study on perch confirms the importance of social facilitation on boldness (Magnhagen and Bunnefeld 2009). Further, habituation to an aspect of the experimental setting has been observed several times in studies of behavioral syndromes: chipmunks decreased their tendency to explore a novel environment with successive trials (Martin and Reale 2008) and great tits (Dingemanse et al. 2002; van Oers et al. 2005b) and zebra finches (Schuett and Dall 2009) increased their tendency to explore with successive trials. Both trends were attributed to habituation, even though the change in behavior in chipmunks was opposite to that in great tits and zebra finches.

If habituation indeed affects the behavior of test subjects in studies of animal personality, this mechanism can explain two common empirical findings. First, habituation may cause bold individuals to be more consistent than shy ones. This was reported for great tits, where slow-exploring birds became faster with age, while fast-exploring ones did not appear to change their behavior (Verbeek et al. 1994; Carere et al. 2005b), and for rodents, where the attack latency of the non-aggressive lines decreased more strongly than that of the aggressive lines (Koolhaas et al. 1999; Gariepy et al. 2001). The reason that these ‘bold’ individuals were more consistent may be because of a ‘ceiling effect’; they were fully habituated and could not explore any faster or attack any quicker.

Second, habituation may cause behavioral correlations across contexts. If some individuals become more quickly familiar with the experimental environment and handling procedures, they develop behavior that is considered ‘bold’, whereas those that have learnt less about their environment appear to have a ‘shy’ personality type. This confirms empirical studies that report that shy individuals score less well on learning tasks (Dugatkin and Alfieri 2003; Magnhagen and Staffan 2003; Sneddon 2003).

The model illustrates an important problem regarding empirical measurements of animal behavior. Even if an individual’s initial tendency to approach the predator, its tendency to deviate from this initial behavior (i.e., its plasticity), and the environment in which the behavior is performed are known, it remains difficult to predict whether an individual will behave boldly or shyly (see also Stamps 2003). This is because chance events affect the experiences that an individual collects and thus the development of its behavior.

The model’s findings may have relevance for natural populations as well. Empirical studies report population-level differences in personality (e.g., Magnhagen 2006; Brown et al. 2007; Herczeg et al. 2009). Assuming that processes in groups in the model inform us about processes in populations in nature, the model suggests that population-level differences may arise from the combined effects of chance and social facilitation; via social facilitation, a few individuals that are acting bold accidentally may have an overwhelming effect on the eventual percentage of individuals considered bold within a population.

A possible shortcoming of our model is that other mechanisms than the ones we studied may have played a role in the experiment of Magnhagen and Staffan (2005). For instance, hunger instead of habituation to the predator might have induced shy individuals in mixed groups to approach the predator increasingly often as the experiment progressed. However, hunger cannot explain the increase over subsequent days in boldness of shy individuals in shy groups. These individuals cannot have become increasingly hungry because they were daily allowed to eat all remaining food after the experiment was ended (Magnhagen and Staffan 2005).

As for the competition mechanism that we used, there are many forms of competition and another form than prior residence may have been important in the empirical data. We tested two alternatives: in one case, we made the feeding rate of an individual dependent on the proportion of food that remained; in the other, we decreased the feeding rate with the number of competitors. Neither alternative stabilized differences in feeding rate among group members because neither allowed for some group members to monopolize the food while competition by prior residence does. Another mechanism that allows for this is social dominance (e.g., McCarthy et al. 1999; Whiteman and Côte 2004). However, group membership must be stable for several weeks for dominance hierarchies to form (Krause et al. 2000), while in the experiment by Magnhagen and Staffan (2005), individuals were together for only a few days.

We tested the effect of initial differences in tendency to approach the predator (as a caricature of initial genetic differences) on the development of individual variation. Unexpectedly, this did not affect the variation in time spent feeding near the predator. However, these initial differences merely concerned the approach probability. The effect of possible other genetic differences that we will investigate in the future concern genetic differences in speed of habituation to the predator (Glowa and Hansen 1994; van Oers et al. 2005b; LaRowe et al. 2006; but see Martin and Reale 2008), in tendency to shoal (Ward et al. 2004), and in size, or combinations of these (e.g., Metcalfe et al. 2003; Westerberg et al. 2004).

In sum, the model shows that differences in behavior that resemble differences in boldness may arise among initially completely identical individuals (i.e., genetic clones) due to differences in previous experience and social environment. Whether the mechanisms of the model (i.e., habituation, social facilitation and competition) play such large roles in the shaping of behavioral differences in real animals remains to be investigated empirically. But as most animal species of which personality is studied are group living during at least part of their lives, it is likely that the social environment is important for the development of their behavior and thus their personality.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Ton Groothuis and Daniel Reid for comments on a previous version.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Bell AM, Hankison SJ, Laskowski KL. The repeatability of behaviour: a meta-analysis. Anim Behav. 2009;77:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Jones F, Braithwaite VA. Correlation between boldness and body mass in natural populations of the poeciliid Brachyrhaphis episcopi. J Fish Biol. 2007;71:1590–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Carere C, Drent PJ, Koolhaas JM, Groothuis TGG. Epigenetic effects on personality traits: early food provisioning and sibling competition. Behaviour. 2005;142:1329–1355. doi: 10.1163/156853905774539328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carere C, Drent PJ, Privitera L, Koolhaas JM, Groothuis TGG. Personality in great tits, Parus major: stability and consistency. Anim Behav. 2005;70:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse NJ, Both C, Drent PJ, Van Oers K, Van Noordwijk AJ. Repeatability and heritability of exploratory behaviour in great tits from the wild. Anim Behav. 2002;64:929–938. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2002.2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dugatkin LA, Alfieri MS. Boldness, behavioral inhibition and learning. Ethol Ecol Evol. 2003;15:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Frost AJ, Winrow-Giffen A, Ashley PJ, Sneddon LU. Plasticity in animal personality traits: does prior experience alter the degree of boldness? Proc R Soc Lond B. 2007;274:333–339. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL, Engel DR. Imitational and social facilitatory aspects of observational learning in laboratory rat. Psychon Sci. 1971;25:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy JL, Bauer DJ, Cairns RB. Selective breeding for differential aggression in mice provides evidence for heterochrony in social behaviours. Anim Behav. 2001;61:933–947. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glowa JR, Hansen CT. Differences in response to an acoustic startle stimulus among 46 rat strains. Behav Genet. 1994;24:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01067931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groothuis TGG, Carere C. Avian personality: characterization and epigenesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow HF, Yudin HC. Social behavior of primates I. Social facilitation of feeding in the monkey and its relation to attitudes of ascendance and submission. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1933;16:171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW, Vanlieshout CFM. Personality development in a social context. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:655–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herczeg G, Gonda A, Merila J. Predation mediated population divergence in complex behaviour of nine-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius) J Evol Biol. 2009;22:544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemelrijk CK, Wantia J. Individual variation by self-organisation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokko H, Lopez-Sepulcre A, Morrell LJ. From hawks and doves to self-consistent games of territorial behavior. Am Nat. 2006;167:901–912. doi: 10.1086/504604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas JM, Korte SM, De Boer SF, Van Der Vegt BJ, Van Reenen CG, Hopster H, De Jong IC, Ruis MAW, Blokhuis HJ. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress physiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:925–935. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause J. Ideal free distribution and the mechanism of patch profitability assessment in 3-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus-aculeatus) Behaviour. 1992;123:27–37. doi: 10.1163/156853992X00093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause J, Hoare D, Krause S, Hemelrijk CK, Rubenstein DI. Leadership in fish shoals. J Fish Biol. 2000;1:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Laland KN, Williams K. Shoaling generates social learning of foraging information in guppies. Anim Behav. 1997;53:1161–1169. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1996.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe SD, Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Kline JP. Personality correlates of startle habituation. Biol Psychol. 2006;72:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessells CM, Boag PT. Unrepeatable repeatabilities - a common mistake. Auk. 1987;104:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Magnhagen C. Risk-taking behaviour in foraging young-of-the-year perch varies with population size structure. Oecologia. 2006;147:734–743. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnhagen C, Bunnefeld N. Express your personality or go along with the group: what determines the behaviour of shoaling perch? Proc R Soc Lond B. 2009;276:3369–3375. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnhagen C, Staffan F. Social learning in young-of-the-year perch encountering a novel food type. J Fish Biol. 2003;63:824–829. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8649.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magnhagen C, Staffan F. Is boldness affected by group composition in young-of-the-year perch (Perca fluviatilis)? Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2005;57:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00265-004-0834-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JGA, Reale D. Temperament, risk assessment and habituation to novelty in eastern chipmunks, Tamias striatus. Anim Behav. 2008;75:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy ID, Gair DJ, Houlihan DF. Feeding rank and dominance in Tilapia rendalli under defensible and indefensible patterns of food distribution. J Fish Biol. 1999;55:854–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00722.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe NB, Valdimarsson SK, Morgan IJ. The relative roles of domestication, rearing environment, prior residence and body size in deciding territorial contests between hatchery and wild juvenile salmon. J Appl Ecol. 2003;40:535–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00815.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shettleworth SJ (1998) Habituation. In: Cognition, evolution, and behavior. Oxford University Press, p 11

- Sih A, Bell AM. Insights for behavioral ecology from behavioral syndromes. Adv Study Behav. 2008;38:227–281. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3454(08)00005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuett W, Dall SRX. Sex differences, social context and personality in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata. Anim Behav. 2009;77:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon LU. The bold and the shy: individual differences in rainbow trout. J Fish Biol. 2003;62:971–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8649.2003.00084.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamps J. Behavioural processes affecting development: Tinbergen’s fourth question comes of age. Anim Behav. 2003;66:1–13. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2003.2180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Post DJ, Hogeweg P. Diet traditions and cumulative cultural processes as side-effects of grouping. Anim Behav. 2008;75:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers K, de Jong G, van Noordwijk AJ, Kempenaers B, Drent PJ. Contribution of genetics to the study of animal personality: a review of case studies. Behaviour. 2005;142:1185–1206. doi: 10.1163/156853905774539364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers K, Klunder M, Drent PJ. Context dependence of personality: risk-taking behavior in a social and a nonsocial situation. Behav Ecol. 2005;16:716–723. doi: 10.1093/beheco/ari045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek MEM, Drent PJ, Wiepkema PR. Consistent individual differences in early exploratory behaviour of male great tits. Anim Behav. 1994;48:1113–1121. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1994.1344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AJW, Thomas P, Hart PJB, Krause J. Correlates of boldness in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2004;55:561–568. doi: 10.1007/s00265-003-0751-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg M, Staffan F, Magnhagen C. Influence of predation risk on individual competitive ability and growth in Eurasian perch, Perca fluviatilis. Anim Behav. 2004;67:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman EA, Côte IM. Dominance hierarchies in group-living cleaning gobies: causes and foraging consequences. Anim Behav. 2004;67:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]