Abstract

Multiple colonic polyps, almost guaranteed colorectal cancer by the age of forty-five and an increased risk of non-colonic cancers characterise the autosomal dominant condition Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) [1]. The patients and families faced with such a diagnosis present many difficult management challenges, both surgical and non-surgical. We discuss the current surgical options for treatment of the more significant manifestations of FAP arising in the colorectum and duodenum as well as desmoid disease

Keywords: familial adenomatous polyposis, colorectal cancer, inherited cancer, treatment

Colorectal disease

Of the many adenomatous polyps which develop in the colon and rectum of patients with FAP, "...one or more of the adenomata form... a malignant adenocarcinoma" [2]. Cancer preventative surgery was instituted in the 1940's. Subsequently screening of patients with a family history of FAP was commenced to ensure that prophylactic treatment, including surgery, was being offered [3]. The timing of prophylactic surgery depends on various factors, such as age. Although there are reports of carcinoma of the rectum developing in children aged less than 10 years [4], elective surgery is usually deferred until after puberty. Quality of life issues for an adolescent are very different from that of an adult, often influenced by schooling, and this is factored into the planning of surgery. Most patients should have been offered a colectomy by the start of their third decade of life, as 15% of FAP patients will present with colorectal cancer before the age of 25 [5]; surveillance usually starts from the age of 10 [6].

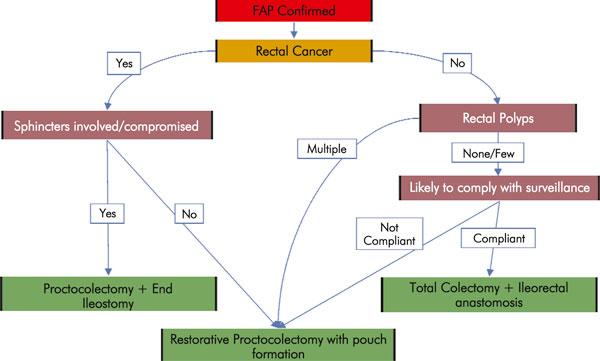

The nature of the prophylactic surgery performed depends on the clinical findings pre-operatively, the patients' wishes and the surgeons' preference (Table 1, Fig. 1) [7].

Table 1.

Indications and advantages of colectomy options in patients with FAP

| Total colectomy + ileorectal anastomosis | Restorative panproctocolectomy | |

|---|---|---|

| Indications | • Rectal sparing | • Rectal cancer |

| • Sparse polyposis | • Multiple rectal polyps | |

| • Compliant with follow-up | • Widespread colorectal polyps | |

| • Non-compliant with follow-up | ||

| Advantages | • Less operative morbidity | • ⇓ Rectal cancer risk |

| • Larger reservoir function | • Less frequent surveillance | |

| Disadvantages | • ⇑ Rectal cancer risk | • Longer procedure |

| • Rectal surveillance every 6 months | • Greater complication rate | |

| • IPAA or ileostomy may be required at a later date | • Likely two-stage procedure | |

| • Poorer functional outcome | ||

Figure 1.

Decision tree for colorectal surgical options in FAP.

Procedure

Total colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis (IRA)

This procedure is unsuitable in patients with marked rectal polyposis and/or rectal carcinoma, or when adequate follow-up and surveillance of the rectal stump cannot be guaranteed [8-10]. The procedure entails mobilisation of the whole colon to the point at which the taeniae coli fuse, considered the upper border of the rectum. Dissection to this level maintains the reservoir function of the rectum and ensures that the anastomosis can be reached with ease by the rigid sigmoidoscope for surveillance purposes. A simple ileorectal anastomosis is fashioned either hand-sewn or stapled. To eliminate blind loops, inaccessible to rigid sigmoidoscopy, formation of an end-to-end anastomosis is recommended [11,12].

Proctocolectomy

This is either total or restorative. The former involves a permanent ileostomy and will not be discussed in detail. The latter, first described in 1978 [13], avoids a permanent stoma by constructing a new reservoir which is re-anastomosed to the anal canal. This panproctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) requires the whole colon and rectum to be mobilised and the large bowel removed by dividing the intestine at the ileocaecal and anorectal junctions. The reservoir is fashioned from the terminal ileum and this in turn is anastomosed to the anal canal.

Indications

The phenotype of the individual FAP patient and any symptoms experienced at presentation are the most important factors determining which surgical procedure is carried out [6,8,9,12].

Operative morbidity and mortality

Total colectomy and IRA are considered a relatively safe procedure with a low operative mortality [9]. There is a fairly steep learning curve with IPAA but the operative mortality can be as good as IRA [14]. IPAA is more likely to be a two-stage procedure with a temporary defunctioning ileostomy requiring subsequent closure often being formed, but such stomas are not always necessary [8,15].

Functional outcome

Whilst increased bowel frequency [8,16] and urgency [16] are common following IRA, patients experience nocturnal defecation [8,17], greater use of anti-diarrhoeal medication [18], and problems with faecal soiling, incontinence and flatus/faeces discrimination [17,19] are more commonly following IPAA procedures. Studies comparing IRA and IPAA procedures have shown similar overall quality of life outcomes [20].

The preservation of the pelvic sympathetic plexus is considered a relative indication for IRA in young men [21].

Post-operative surveillance

Ileorectal anastomosis

Having an IRA implies lifelong surveillance with a minimum of rigid sigmoidoscopy every 6 months [6], although sigmoidoscopy every 4 months has been suggested [5]. Standard polyp surveillance should be carried out with all remaining polyps removed [22]. A combination of snare polypectomy or diathermy is appropriate. The risk of rectal cancer increases with chronological age rather than time from surgery [5,11,12] with an approximately 25% risk of rectal cancer by the age of 70 years [11]. The cumulative risk for rectal excision following IRA may be as high as 60% for those aged 70 years [11].

Bjork et al found many of the rectal cancers had developed very close to the anal verge, a notoriously difficult area to assess with the rigid sigmoidoscope [11]. In a like manner, patients in whom an IRA has been constructed higher than 12 cm from the anal verge are more likely to develop rectal cancer as the rectum cannot be adequately assessed in rigid sigmoidoscopy [11,12]. Older age at the time of IRA and multiple/dense pre-operative polyps are additional risk factors for the development of rectal cancer; however, these factors would preclude a patient from receiving an IRA today. Church et al investigated this, finding that in the past all patients were offered a sphincter sparing procedure (IRA) before IPAA became widely available. They found that all patients with very severe polyposis had an IRA in the pre-pouch era and only 39% with severe polyposis had chosen this in the pouch era [23]. They hypothesised and showed, albeit with a shorter period of follow-up, that patients who have an IRA in the pouch-era have a lower risk of post IRA rectal cancer than those operated during the pre-pouch era. Attributing this to patient selection (that is, those with less severe phenotypes now receive an IRA) they cautioned that the choice of surgery now should not be influenced by data that were generated before the current range of surgical options became available.

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis

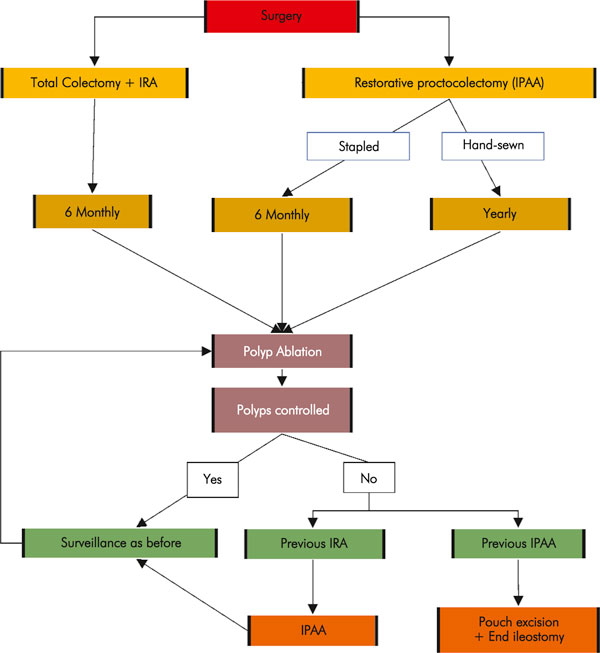

With increasing reports of adenomas [24,25] and even carcinomas [26] in pouches, regular surveillance of these is advocated, with most groups suggesting annual rigid sigmoidoscopy [6] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Decision tree for surveillance following colonic surgery in FAP.

Controversies in IPAA

As FAP is primarily a mucosal disease it seems logical to remove all the colorectal mucosa to prevent polyps and ultimately cancer developing at a later date. Mucosectomy was an essential part of Parks and Nicholls' original description [13]. To avoid this time-consuming component of restorative proctocolectomy double stapled anastomoses are used [19,27-29]. Stapled anastomoses leave a greater cuff of mucosa than that left following mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis [30], with pouch/anal polyps seen more commonly following stapled than with hand-sewn IPAA [30].

Patients subjected to a hand-sewn anastomosis are more likely to experience a poorer functional outcome [14,29], with increased bowel action and faecal incontinence more common [29]. This may be a consequence of the anal stretch required to facilitate the anastomosis, or the removal of the anal transitional zone during the mucosectomy [26]. The anal transitional zone, a highly innervated area 1 cm above the dentate line, is believed to be responsible for the discrimination of faeces and flatus [26,31]. Pouch-anal strictures do occur, with reported rates as high as 42% [27,29]. They are more commonly found following stapled anastomoses [27]. Strictures following stapled anastomoses tend to be less troublesome and more amenable to simple dilatation than those which occur in hand-sewn anastomosis; which are inclined to be more severe, requiring operative dilatation [27].

Pouchitis, often seen in IPAA procedures carried out for inflammatory bowel disease [32], is very unusual in FAP patients [17,29].

Duodenal polyposis

Extra-colonic polyps have been described in the stomach and duodenum of FAP patients for over 100 years [1], but their true incidence and significance were only fully documented in the late 1980's [33,34]. It is now recognised that up to 90% of FAP patients will develop duodenal polyposis by the age of 70 [35], and once colectomy has been carried out duodenal cancer is one of the main causes of death in FAP patients [36,37]. As part of their prospective study of duodenal polyposis in FAP patients, Spigelman et al defined a now widely used classification score for severity of duodenal polyposis [33] (Table 2a).

Table 2a.

Spigelman Staging [33] of Duodenal Polyposis

| Points assigned | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| No. of polyps | 1 to 4 | 5 to 20 | >20 |

| Polyp size (mm) | 1 to 4 | 5 to 10 | >10 |

| Histology | tubular | tubulovillous | villous |

| Dysplasia | mild | moderate | severe |

| Scoring system: | |||

| Stage 0 = 0 points | |||

| Stage I = 1 to 4 points | |||

| Stage II = 5 to 6 points | |||

| Stage III = 7 to 8 points | |||

| Stage IV = 9 to 12 points | |||

Surveillance

The first surveillance upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be carried out by the age of 25-30 [36,38,39]. This should then be followed up by a further endoscopy 12 months later [36], and a Spigelman stage derived. Random biopsies of apparently normal mucosa should also be taken initially, with Bulow et al finding 12% of adenomas in their series to be invisible [35]. The region of the ampulla is of considerable importance and this is best viewed and biopsied with a side or oblique-viewing endoscope [33]. A suitable surveillance program based on the Spigelman stage is then employed [40] (Table 2b). Disease progression does occur and Spigelman stage IV patients have a crude risk of developing duodenal cancer of 36% [40], compared with 2% for those with stage II or III disease.

Table 2b.

Suggested surveillance/treatment for Duodenal Polyposis based on Spigelman Staging [38]

| Spigelman stage | Endoscopic surveillance | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | 5 yearly | - |

| Stage I | 5 yearly | - |

| Stage II | 3 yearly | No surgery Chemoprevention equivocal |

| Stage III | 1-2 yearly | Surgery equivocal Chemoprevention offered |

| Stage IV | 6 monthly | Surgery offered Chemoprevention offered |

Endoscopic treatments

Various endoscopic treatments have been used to control duodenal adenomas locally. These include polyp ablation by electro-diathermy, Nd-YAG laser, ionised argon diathermy, photodynamic therapy, snare polypectomy and mucosal resection [38,39]. These procedures have a risk of complications including bleeding, perforation, and pancreatitis as well as late-onset duodenal stenosis [39]. Recurrence is also likely [36,41], making the decision to persevere with further endoscopic treatments or proceed to surgery a difficult one.

Surgery

If duodenal carcinoma has developed a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple's or modified Whipple's procedure) should be carried out [39]. For patients with benign adenomatous change but Spigelman stage IV less radical surgery can be performed. Recent advances in surgical technique have resulted in pancreas or pylorus sparing duodenectomy being carried out [41-43]. Such procedures involve resection of the whole of the duodenum with its associated malignant potential, preserving the function of the pylorus and/or the pancreas. This is of considerable importance to patients who have already had a colectomy, as daily bowel movements can be doubled, particularly in patients with an IPAA [41].

Chemoprevention

Trials of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) Sulindac and Celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor) have shown regression of duodenal polyps [44] and their use is probably best reserved for patients with stage III or IV (initially) polyposis [38].

Future developments

Jejunal and ileal polyps occur in FAP patients [42]. The advent of capsule endoscopy will allow for a more precise estimation of their prevalence and natural history. Similar advances in CT imaging herald hope for less invasive surveillance of the duodenum [45].

Desmoid disease

Desmoid tumours account for 0.03% of all tumours in the non-FAP population, but occur in up to 32% of those with FAP [46]. They result from proliferation of myofibroblasts [47], arising within the abdomen or the abdominal wall in FAP patients. They are more common in women, particularly in the non-FAP population, leading to the suggestion that female hormones may play some role in their development [48,49]. There is a tendency for desmoids to run in certain FAP families and previous trauma or surgery is thought to initiate their development. The St. Mark's group have described early desmoid tumour type lesions (desmoid precursor lesion) in people who have no history of surgery or trauma [50] but their significance has yet to be fully assessed.

Desmoid tumours are classified as benign as they do not spread to distant sites; however they are potentially lethal when they occur within the abdominal cavity by surrounding other structures such as small or large bowel, ureters and the mesentery [51].

Surgery

Desmoid tumours of the abdominal wall and the extremities

It is recommended that surgery should include excision of the mass with some surrounding tissue. This can be done with relatively few complications but the recurrence rate varies from 10% to 68% [46].

Desmoid tumours within the abdomen

Surgery is often technically demanding and may even be impossible. The complication rate is high with a post-operative mortality rate of anywhere between 10% and 60%, and a recurrence rate of up to 78% [46]. It is recommended that desmoid tumours should only be surgically removed when bowel obstruction has occurred or when the blood supply to the bowel has been compromised. As operative removal is complex this should be done by experienced surgeons [7,52].

A recent report found the presence of incidental desmoid tumours at laparotomy for colectomy that required modifications or precluded the intended procedure from being carried out in 26% of 266 patients [47].

With a risk of recurrence following surgical removal, various other treatment modalities have been trialled.

Other treatment modalities

Commonly used NSAIDs like Sulindac have been shown to cause some reduction in the size or to halt further enlargement of desmoid tumours [53,54]. Anti-oestrogen drugs such as Tamoxifen have been studied, in conjunction with NSAIDs, providing similar results to the use of NSAIDs alone [54-56]. Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been found to be similarly effective as the NSAIDs and anti-oestrogens but with more marked side effects. The use of chemotherapy is currently reserved for large inoperable desmoid tumours that have not responded to other drug treatments [57-60]. Radiotherapy is not recommended in FAP, as most tumours are within the abdomen and unacceptable post-treatment complications affecting the small bowel may occur [7,46]. Warfarin, Prednisolone and Interferon have been used, but without evidence from clinical trials [46,61].

Summary of treatment options

For desmoid tumours of the abdominal wall and extremities wide surgical excision is recommended. If recurrent, further surgery may be attempted and radiotherapy may be used for tumours of the extremities [51].

Intra-abdominal desmoid tumours should be assessed every 6-12 months with CT scan and medical management with NSAIDs (Sulindac) with Tamoxifen may be beneficial. Renal tract obstruction may require ureteric stent insertion [53]. If progression occurs the dose of Sulindac can be increased and Tamoxifen replaced with Toremifene [46]. This should be maintained for several years before dose reduction is considered. If further progression of the desmoid tumour occurs or they become more symptomatic surgery may be attempted either to remove the desmoid tumours if a small discrete mass and no vital structures are involved; or palliative surgery to relieve the symptoms. When surgery is not possible or there has been subsequent recurrence then cytotoxic chemotherapy may be considered [46].

Prognosis

About 4-6% of desmoid tumours resolve spontaneously [46,52]. Desmoid tumours cause significant morbidity and in cases of unresectable mesenteric desmoid tumours the mortality rate has been reported to be as high as 30%. The overall survival rate after 10 years is 63% [46].

Surveillance and cancer registries

The importance of familial cancer registries cannot be underestimated. The familial cancer registry undertakes the time-consuming task of documenting the full family pedigree, followed by the requisite genetic counselling [62]. They may also coordinate genetic testing as appropriate, family member contact and provide assistance to ensure that surveillance is being performed. It is noteworthy that "all published data from cancer prevention programmes that have reduced cancer incidence in family members... have used family [cancer] registries" [63].

Conclusion

Surgical management of FAP has improved over the years with a greater emphasis on preventative/prophylactic surgery. Deciding which prophylactic large bowel procedure is difficult. With such prophylactic procedures almost eliminating the risk of colorectal cancer, patients with FAP now face new challenges from duodenal polyposis and desmoid disease.

References

- Phillips RKS, Spigelman AD, Thomson JPS. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis and Other Polyposis Syndromes. Edward Arnold, London; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart-Mummery JP. The causation and treatment of multiple adenomatosis of the colon. Ann Surg. 1934;99:177–184. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193401000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent KP, Northover J. In: Familial Adenomatous Polyposis and Other Polyposis Syndromes. Phillips RKS, Spigelman AD, Thomson JPS, editor. Edward Arnold, London; 1994. Total colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles DM, Lunt PW, Wallis Y, Griffiths M, Sandhu B, McKay S, Morton D, Shea-Simonds J, Macdonald F. An unusually severe phenotype for familial adenomatous polyposis. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:431–435. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.5.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent KP, Phillips RK. Rectal cancer risk in older patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and an ileorectal anastomosis: a cause for concern. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1204–1206. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800791136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Half EE, Bresalier RS. Treatment of hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:213–224. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen HF, Bulow S. The Leeds Castle Polyposis Group. Guidelines for the surveillance and management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a world wide survey among 41 registries. Colorect Dis. 1999;1:214–221. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.1999.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden MV, Neale KF, Nicholls RJ, Landgrebe JC, Chapman PD, Bussey HJ, Thomson JP. Comparison of morbidity and function after colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:789–792. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen HF, van Duijvendijk P, Buskens E, Bulow C, Bjork J, Jarvinen HJ, Bulow S. Decision analysis in the surgical treatment of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: a Dutch-Scandinavian collaborative study including 659 patients. Gut. 2001;49:231–235. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork J, Akerbrant H, Iselius L, Svenberg T, Oresland T, Pahlman L, Hultcrantz R. Outcome of primary and secondary ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and ileorectal anastomosis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:984–992. doi: 10.1007/BF02235487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JA, Akerbrant HI, Iselius LE, Hultcrantz RW. Risk factors for rectal cancer morbidity and mortality in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1719–1725. doi: 10.1007/BF02236857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulow C, Vasen HF, Jarvinen H, Bjork J, Bisgaard ML, Bulow S. Ileorectal anastomosis is appropriate for a subset of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterol. 2000;119:1454–1460. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1978;2:85–88. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6130.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther K, Braunrieder G, Bittorf BR, Hohenberger W, Matzel KE. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis experience better bowel function and quality of life after ileorectal anastomosis than after ileoanal pouch. Colorect Dis. 2003;5:38–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg K, Liljeqvist L. Stapled ileoanal pouches without loop ileostomy: a prospective study in 86 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:221–227. doi: 10.1007/s003840100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JF, Ho YH. Total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis leads to appreciable loss in quality of life irrespective of primary diagnosis. Tech Coloproctol. 2001;5:79–83. doi: 10.1007/s101510170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork J, Akerbrant H, Iselius L, Bergman A, Engwall Y, Wahlstrom J, Martinsson T, Nordling M, Hultcrantz R. Periampullary adenomas and adenocarcinomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: cumulative risks and APC gene mutations. Gastroenterol. 2001;121:1127–1135. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel SA, Newman M, Sharp KW. Ileoanal pouch versus ileostomy: is there a difference in quality of life? Am Surg. 2000;66:540–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvendijk P, Slors JF, Taat CW, Oosterveld P, Vasen HF. Functional outcome after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis compared with proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg. 1999;230:648–654. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199911000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvendijk P, Slors JF, Taat CW, Oosterveld P, Sprangers MA, Obertop H, Vasen HF. Quality of life after total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:590–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Pikarsky AJ, Potenti FM, Lau CW, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Are complications of subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis related to the original disease. Am Surg. 2001;67:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church J, Burke C, McGannon E, Pastean O, Clark B. Risk of rectal cancer in patients after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis: a function of available surgical options. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1175–1181. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge IG, Swain DJ, Groves CJ, Saunders BP, Windsor AC, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK. Large villous adenomas arising in ileal pouches in familial adenomatous polyposis: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:123–126. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parc Y, Piquard A, Dozois RR, Parc R, Tiret E. Long-term outcome of familial adenomatous polyposis patients after restorative coloproctectomy. Ann Surg. 2004;239:378–382. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000114216.90947.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrouenraets BC, Van Duijvendijk P, Bemelman WA, Offerhaus GJ, Slors JF. Adenocarcinoma in the anal canal after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis using a double-stapled technique: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:530–534. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi HL, Brand MI, Saclarides TJ. Anal complications after restorative proctocolectomy (J-pouch) Am Surg. 2002;68:628–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijvendijk P, Vasen HF, Bertario L, Bulow S, Kuijpers JH, Schouten WR, Guillem JG, Taat CW, Slors JF. Cumulative risk of developing polyps or malignancy at the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:325–330. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(99)80075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CJ, Solomon MJ, Eyers AA, West RH, Martin HC, Glenn DC, Morgan BP, Roberts R. Evolution of the pelvic pouch procedure at one institution: the first 100 cases. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:438–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slors JF, Ponson AE, Taat CW, Bosma A. Risk of residual rectal mucosa after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal reconstruction with the double-stapling technique. Post-operative endoscopic follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:207–210. doi: 10.1007/BF02052453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N, Seow-Choen F. Physiological and functional outcome following ultra-low anterior resection with colon pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1029–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Talbot IC, Domizio P, Phillips RK. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1989;2:783–785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90840-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church JM, McGannon E, Hull-Boiner S, Sivak MV, Van Stolk R, Jagelman DG, Fazio VW, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW. Gastroduodenal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1170–1173. doi: 10.1007/BF02251971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulow S, Bjork J, Christensen IJ, Fausa O, Jarvinen H, Moesgaard F, Vasen HF. DAF Study Group. Duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2004;53:381–386. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi H, Spigelman AD. Gastroduodenal lesions in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Surg Today. 2000;30:675–682. doi: 10.1007/s005950070077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagelman DG, DeCosse JJ, Bussey HJ. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1988;1:1149–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Correa M, Giardiello FM. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:885–894. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JC, DiSario JA, Grady WM. Surveillance and Treatment of Periampullary and Duodenal Adenomas in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves CJ, Saunders BP, Spigelman AD, Phillips RK. Duodenal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): results of a 10 year prospective study. Gut. 2002;50:636–641. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.5.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morpurgo E, Vitale GC, Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Ziegler C, Polk HC Jr. Clinical characteristics of familial adenomatous polyposis and management of duodenal adenomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalady MF, Clary BM, Tyler DS, Pappas TN. Pancreas-preserving duodenectomy in the management of duodenal familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:82–87. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(01)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento JM, Thompson GB, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for duodenal polyposis. Arch Surg. 2002;137:557–562. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.5.557. discussion 562-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Lynch PM, Hawk E, Gordon GB, Saunders BP, Wakabayashi N, Shen Y, Zimmerman S, Godio L, Rodrigues-Bigas M, Su LK, Sherman J, Kelloff G, Levin B, Steinbach G. FAP Study Group. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of Celecoxib, a selective cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitor, on duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2002;50:857–860. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SA, Halligan S, Moore L, Saunders BP, Gallagher M, Phillips RKS, Bartram CI. Multidetector-row CT duodenography in familial adenomatous polyposis: a pilot study. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:939–945. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen AL, Bulow S. Desmoid tumour in familial adenomatous polyposis. A review of literature. Fam Cancer. 2001;1:111–119. doi: 10.1023/A:1013841813544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley JE, Church JM, Gupta S, McGannon E, Fazio VW. Significance of incidental desmoids identified during surgery for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:334–338. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0063-0. discussion 339-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitamo JJ, Hayry P, Nykyri E, Saxen E. The desmoid tumor. I. Incidence, sex-, age- and anatomical distribution in the Finnish population. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;77:665–673. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/77.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitamo JJ, Scheinin TM, Hayry P. The desmoid syndrome. New aspects in the cause, pathogenesis and treatment of the desmoid tumor. Am J Surg. 1986;151:230–237. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SK, Smith TG, Katz DE, Reznek RH, Phillips RK. Identification and progression of a desmoid precursor lesion in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:970–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer KCR, Hawley PR, Phillips RKS. In: Familial Adenomatous Polyposis and Other Polyposis Syndromes. Phillips RKS, Spigelman AD, Thomson JPS, editor. London: Edward Arnold; 1994. Desmoid Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SK, Neale KF, Landgrebe JC, Phillips RK. Desmoid tumours complicating familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1185–1189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SK, Phillips RK. Desmoids in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1494–1504. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada K, Church JM, Jagelman DG, Fazio VW, McGannon E, George CR, Schroeder T, Lavery I, Oakley J. Non-cytotoxic drug therapy for intra-abdominal desmoid tumor in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:29–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02053335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell WR, Kirsch WM. Testolactone, sulindac, warfarin, and vitamin K1 for unresectable desmoid tumors. Am J Surg. 1991;161:416–421. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)91102-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann A, Adolph C, Vogel T, Unger A, Moeslein G. High-dose tamoxifen and sulindac as first-line treatment for desmoid tumors. Cancer. 2004;100:612–620. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L, Blackstein M, Berk T, McLeod RS, Gallinger S, Madlensky L, Cohen Z. Chemotherapy for desmoid tumours in association with familial adenomatous polyposis: a report of three cases. Can J Surg. 1996;39:247–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janinis J, Patriki M, Vini L, Aravantinos G, Whelan JS. The pharmacological treatment of aggressive fibromatosis: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:181–190. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risum S, Bulow S. Doxorubicin treatment of an intra-abdominal desmoid tumour in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:585–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler M, Cohen Z, Blackstein M, Berk T, Gallinger S, Madlensky L, McLeod R. Chemotherapy for desmoid tumors in association with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:798–801. doi: 10.1007/BF02055435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Otterson MF, Shidham VB, Binion DG. Antiangiogenic treatment of mesenteric desmoid tumors with toremifene and interferon alfa-2b: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath DR, Spigelman AD. Hereditary colorectal cancer: keeping it in the family - the bowel cancer story. Intern Med J. 2002;32:325–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2002.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines for the Prevention, Early Detection and Management of Colorectal Cancer. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra; 1999. [Google Scholar]