Abstract

Molecular aberrations of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and/or MDM2/p53 signaling pathways have been reported in 80% and 50% of primary AML samples and confer poor outcome. In this study, anti-leukemic effects of combined MEK inhibition by AZD6244 and non-genotoxic p53 activation by MDM2 antagonist Nutlin3a were investigated. Simultaneous blockade of MEK and MDM2 signaling by AZD6244 and Nutlin3a triggered synergistic proapoptotic responses in AML cell lines (CI = 0.06 ± 0.03 and 0.43 ± 0.03 in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells, respectively) and in primary AML cells (CI = 0.52 ± 0.01). Mechanistically, the combination upregulated levels of BH3-only proteins Puma and Bim, in part via transcriptional up-regulation of the FOXO3a transcription factor. Suppression of Puma and Bim by short interfering RNA rescued OCI/AML3 cells from AZD/Nutlin-induced apoptosis. These results strongly indicate therapeutic potential of combined MEK/MDM2 blockade in AML and implicate Puma and Bim as major regulators of AML cell survival.

Keywords: MEK inhibitor, MDM2 antagonist, Combination therapy, Apoptosis, Acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs) are clonal malignancies of the hematopoietic stem cell. Many aberrant molecular events have been implicated in leukemogenesis. For example, constitutive activation of the MAPK signaling pathway is reported in more than 80% of primary AML samples (1) and was identified by us as an independent prognostic factor in patients with AML (2). Further, overexpression of the Murine double minute (MDM2) protein is present in 50% of AML (3). MDM2 not only rapidly degrades p53 through its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (4) but is also up-regulated by p53 at the transcriptional level as a negative feedback loop of p53 activity (5). Interestingly, simultaneous loss-of-function p53 and MAPK (Ras) activation was shown to be synergistic in the malignant transformation of murine and human colon cells, and the overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 with concomitant activation of MAPK (Ras) signaling induces AML in mice. (6–8)

Targeting special signaling pathways with small-molecule inhibitors is a potential novel therapeutic strategy for AML. Several small-molecule inhibitors of Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway including CI-1040, PD98059, sorafenib and U0126 were characterized by us and others in AML models (IC50s between 0.03 to 5.4 µM), but as single agents they so far showed only modest efficacy in clinical trials (9–13). Recently, a second-generation highly selective allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/2, AZD6244 (AstraZeneca, also known as ARRY-142886), was reported to inhibit basal phosphorylation of ERK in a series of human tumor cell lines, with an IC50 in the range of 10 nM . Based on its reported anti-tumor efficacy in solid tumors models of hepatocellular, colon, myeloma, thyroid, and cutaneous cancer, AZD6244 has recently entered c1linical trials (14–19)1. Our study in human leukemic cell lines has demonstrated that AZD6244 suppressed Rb phosphorylation and modulated cell cycle–related proteins which resulted in G1 cell cycle arrest in AML cells with constitutively activated ERK. (20)

However, similar to other MAPK inhibitors, AZD6244 as a single agent functions as a cytostatic rather than cytotoxic agent in malignancies (20, 21). Hence, combination therapeutic strategies that target multiple signaling pathways might enhance its pro-apoptotic potential. For example, a small-molecule antagonist of MDM2, Nutlin3a, which induces wild-type, unmutated p53, has been shown by us to induce apoptosis in AML (22). We have recently reported that the combination of MEK inhibitor PD98059 and Nutlin3a induces synergistic proapoptotic effects in leukemia cells (23); however, the mechanisms underlying that activity were not fully understood. In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying anti-leukemic efficacy of AZD6244 and Nutlin3a in AML.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) was provided by Dr. Paul Smith, AstraZeneca, and Nutlin3a was supplied by Dr. Lyubomir T. Vassilev, Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ. All other chemicals and solvents used were of the highest grade commercially available.

Cell lines and primary AML samples

The human AML cell lines HL60, U937, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), OCI/AML3 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Mark D Minden (Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), and MOLM13 cells were obtained from the Fujisaki Cell Center, Hayashibara Biochemical Labs, Inc., Okayama, Japan. OCI/AML3-p53shRNA and OCI/AML3-Vector cells were generated by retroviral infection with p53 shRNA plus GFP or GFP-only expressing gene, as previously described (24).

Primary peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were obtained from patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed and/or refractory AML (supplemental Table 1 is available online). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient according to institutional guidelines.

All cells, including primary patient samples, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability was assessed using the trypan blue dye exclusion method, and apoptosis was determined by annexin V positivity detected by flow cytometry, as previously described (25).. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot

For immunoblot analysis, the cells were treated with the indicated agents and then collected in lysis buffer(26). For analysis of the protein levels in different fractions of the cells, a nuclear extraction kit (Active Motif) was used for separating cytosolic and nuclear fractions following the manufacturer’s instructions. The semiquantitative immunoblotting data were generated by using Scion imaging software (Beta 4.03; Scion Corporation).

TaqMan real-time RT-PCR

OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of AZD6244 and/or Nutlin3a for 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated and first-strand cDNA was generated using random hexamers. The mRNA expression levels of FOXO3a, Puma, Bim, Mcl-1 and Abl-1 were quantified using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems), as previously described (27).. The real-time PCR experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Simultaneous targeting of multiple signaling pathways

Cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium at 3 × 105/ml and were treated with varying concentrations of the signaling inhibitors AZD6244 and/or Nutlin3a for 48 hours. The induction of apoptosis was determined by measuring the percentage of annexin V–positive cells with flow cytometry. The isobologram and combination index analyses were performed using CalcuSyn software (BioSoft), a widely used method for evaluating combinatorial synergy between cancer therapeutic agents (28).

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal analysis

OCI/AML3 cells were treated with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a for 24 hours. The cells were then immunostained with indicated antibodies and observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope system, as previously described.(13)

Cell transfection with siRNAs

For knockdown of Puma, Bim and FOXO3a proteins, the indicated siRNAs and mock control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon Research, Inc. Transfections of OCI/AML3 leukemia cells were carried out by electroporation using the Nucleofection system (T-solution, X-001; Amaxa), following the manufacturer's instructions. The final concentration of siRNA was 200 nM. After 24 hours of transfection, the indicated concentrations of AZD6244 and Nutlin3a were added to the cells for an additional 6 or 24 hours of culturing. Apoptosis induction was determined by measuring the percentage of annexin V–positive cells via flow cytometry, and expression level of the relative proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was used to analyze the immunoblot, cell growth, and apoptosis data. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For evaluating the synergistic efficacies of AZD6244 and Nutlin3a, combination index (CI) values were determined according to the method of Chou and Talalay (29). A combination index value of 1 indicates an additive effect, a value of less than 1 indicates synergy, and a value of greater than 1 indicates antagonism. The average combination index values were calculated at different effect levels (50% effective concentration [EC50], EC75, and EC90). All statistical tests were 2 sided.

The details of the materials and methods including antibodies, cell lines, Western blot analyses, TaqMan real-time RT-PCR, immunofluorescence staining and confocal analyses are available online as supplementary information.

Results

Simultaneous targeting of MEK and MDM2 synergistically inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in human AML cells

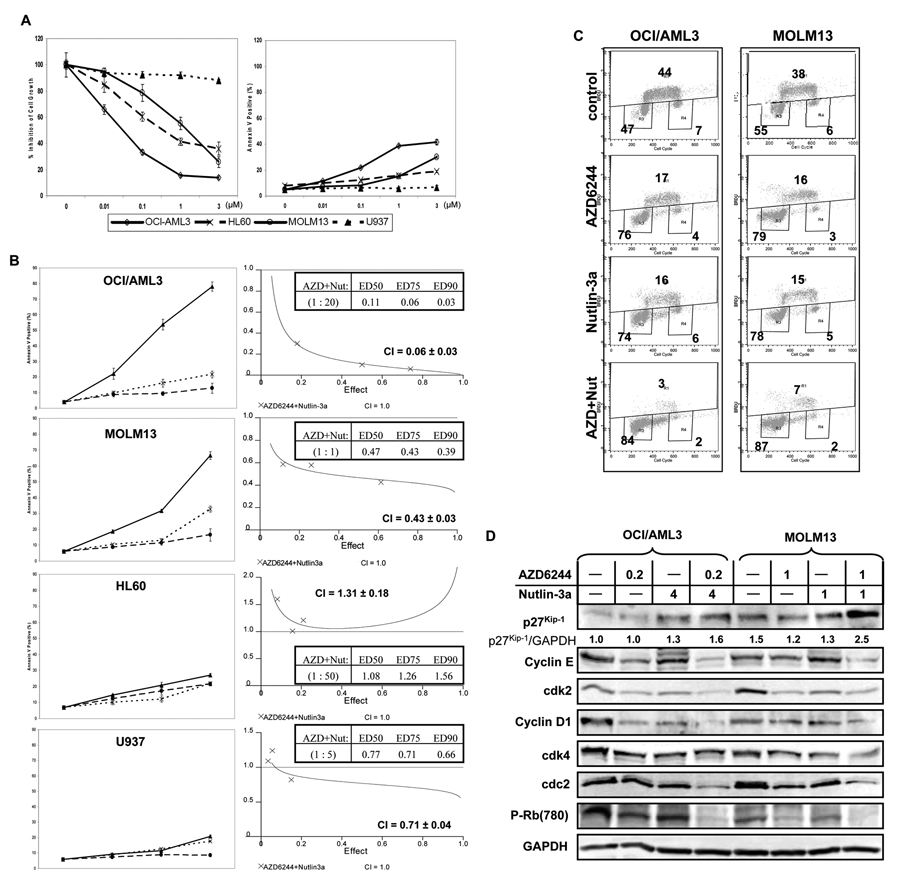

We first examined the effects of MEK inhibitor AZD6244 on cell growth and apoptosis of human AML cell lines. AML cells with constitutively activated ERK (e.g. OCI/AML3, HL60, and MOLM13 lines) were more sensitive to AZD6244-induced growth inhibition than U937 cells, which have a lower basal level of phospho-ERK: the mean IC50 values were 0.03 µM (95% CI = 0.01 to 0.08 µM), 0.6 µM (95% CI = 0.3 to 1.2 µM), and 0.7 µM (95% CI = 0.5 to 1.0 µM), respectively, compared to 40.4 µM (95% CI = 33.0 to 49.3 µM for U937 cells). However, only moderate iduction of apoptosis induction was observed at sub-micromolar concentrations (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Combined effects of AZD6244 and Nutlin3a on cell growth and apoptosis of human AML cell lines. (A) OCI/AML3, MOLM13, HL60, and U937 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of AZD6244 for 72 hours. Inhibition of cell growth and apoptosis were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Growth inhibition was expressed as percentage relative to that in the control group. Data represent the mean of three independent determinations. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. (B) OCI/AML3, MOLM13, HL60, and U937 cells were treated simultaneously with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a using a fixed ratio as indicated and Annexin V positivity was measured by flow cytometry after 48 hours. Combination index (CI) values were determined by isobologram analysis. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. (C) OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of AZD6244 and/or Nutlin-3a for 24 hours, after which cells were pulsed with BrdU for 45 minutes and BrdU incorporation was analyzed by flow cytometry following anti-BrdU staining. (D) Expression of cell cycle-related check-point proteins was determined by immunoblotting after 24 hours of AZD6244/Nutlin3a treatment.

In an effort to enhance proapoptotic effects of AZD6244 in leukemia cells, we combined MDM2 antagonist Nutlin3a with AZD6244. Results showed synergistic apoptosis induction in p53 wild type cells OCI/AML3 (CI = 0.06 ± 0.03) and MOLM13 (CI = 0.43 ± 0.03), but no significant proapoptotic effect was observed in cells with dysfunctional p53 (p53-null HL-60 and p53-mutated U937) (Figure 1B).

To further investigate whether the combination treatment in the sensitive cell lines affects cell cycle progression, BrdU incorporation assay was determined by anti-BrdU staining of pulsed OCI/AML3 or MOLM13 after AZD6244 and/or Nutlin-3a treatment. Results indeed demonstrated reduction of percentage of cells entering S phase upon combined treatment (Figure 1C), suggesting that simultaneous targeting of MEK and MDM2 signaling inhibits cell growth by arresting cells in G1 phase. Further investigations showed up-regulation of p27Kip-1 and down-regulation of G1 phase-related check-point proteins cyclin E/cdk2, cyclin D1/cdk4 complexes, cdc2 and phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein (Rb) in the sensitive cells OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 after combination treatment (Figure 1D).

Combined MEK/MDM2 blockade modulates Puma, Bim, Mcl-1 and phosphorylated FOXO3a levels

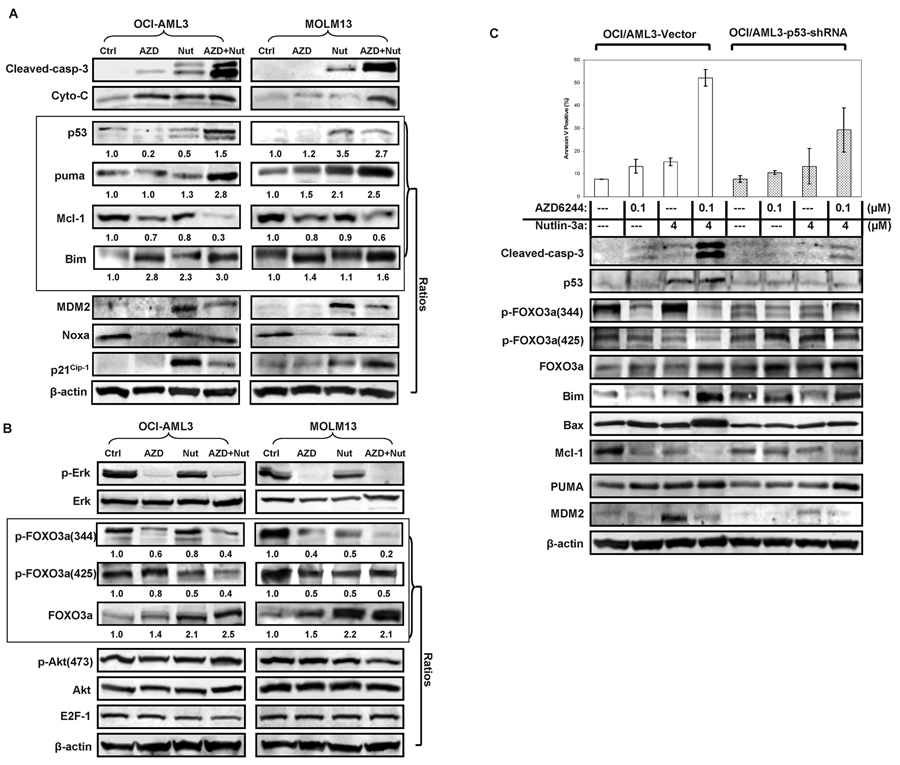

To elucidate mechanisms of synergistic proapoptotic effects of the AZD6244 and Nutlin-3a combination, apoptosis-related proteins were further investigated by Western blot. Up-regulation of p53, Puma (p53–up-regulated modulator of apoptosis), Bim (Bcl-2–interacting mediator of cell death), and down-regulation of Mcl-1 (Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1) protein levels was observed in cells co-treated with AZD/Nutlin, which exceeded the changes caused by either drug alone. Nutlin-3a induced MDM2 as previously reported but this effect was blunted upon combined treatment. In turn, p21 and Noxa were modified differently in OCI/AMl3 and MOLM13 cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells were treated with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a for 24 hours. The expression of (A) apoptosis-related proteins and (B) transcription factor FOXO3a and its downstream targets were analyzed by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) OCI/AML3-Vector and OCI/AML3-p53-shRNA cells were treated at the indicated concentrations of AZD6244 and Nutlin3a as single agents and in combination for 24 hours. Apoptosis was determined as described in Materials and Methods, and the expression profiles of apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed using immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control.

We next investigated modulation of expression of the transcription factor FOXO3a, a known modulator of Bim expression. Interestingly, AZD6244 as a single agent profoundly suppressed FOXO3a phosphorylation at the Ser 344 and less so at the Ser 425 site, and combined treatment further suppressed FOXO3a phosphorylation at both sites and upregulated total FOXO3a level. On the contrary, the levels of phosphorylated Akt and E2F-1 were not significantly affected by the treatment in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells (Figure 2B). To further investigate the role of p53 in the modulation of related proteins and apoptosis induction, we utilized p53-knockdown cells (OCI/AML3-p53-short-hairpin [sh]RNA) and their respective vector-transduced cells (OCI/AML3-Vector). AZD6244 and AZD6244/Nutlin3a blocked phosphorylated FOXO3a in p53 wild-type cells but not in cells with silenced p53 (Figure 2C). Notably, basal levels of total FOXO3a were higher in p53 knock down OCI/AML3 than in p53 wild type cells and combination treatment upregulated total FOXO3a in a p53 independent fashion. BH3-only proapoptotic protein Bim showed a pattern similar to that of total FOXO3a. In addition, downregulation of Mcl-1 and upregulation of Bax were more significant in p53 wild-type as compared to p53-knockdown OCI/AML3 cells. Likewise, apoptosis induction was higher in the p53 wild-type cells than that in the p53-knockdown cells (52% vs. 29% annexin V-positive cells). However, pro-apoptotic protein Puma was lower in p53-knockdown cells but was induced by the AZD/Nutlin combination in both cell types. MDM2 induction by Nutlin 3a was profound, as expected, in a p53-dependent fashion, but this induction was inhibited by AZD6244 (Figure 2C).

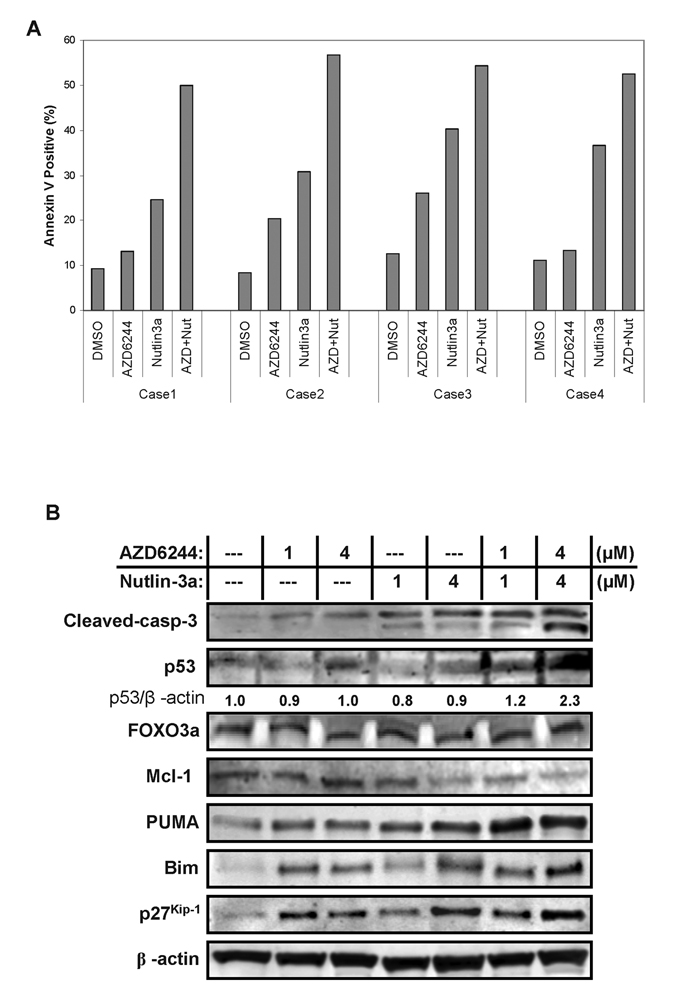

Furthermore, effects of AZD6244 and/or Nutlin3a treatment were investigated in four primary AML samples. The combination treatment enhanced apoptosis induction in both peripheral blood (samples #2–4) and bone marrow blasts (sample #1). The mean combination index was 0.52 ± 0.01 (Figure 3A). This was associated with upregulation of Puma and Bim and downregulation of Mcl-1, with little change in FOXO3a protein expression (Figure 3B). While samples #1 and #3 were derived from AML patients harboring FLT3-ITD mutation, comparable increase in apoptosis was observed in all 4 samples tested.

Figure 3.

The effects of combined targeting of MEK/MDM2 signaling on AML patients ex vivo. (A) Peripheral blood and bone marrow blasts from patients with AML were treated with AZD6244 (4 µM) and Nutlin3a (4 µM) for 24 hours ex vivo, and apoptosis was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The expression of apoptosis-related proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting in sample # 2. β-actin was used as a loading control.

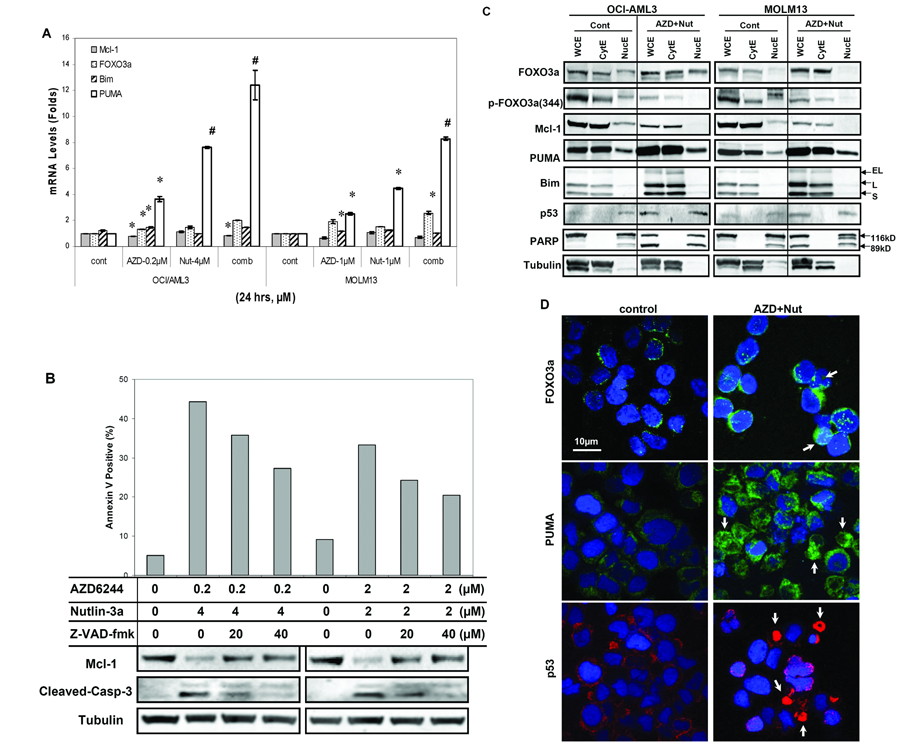

Next, we further examined the mechanisms of changes in protein expression by determining mRNA levels of FOXO3a, Puma, Bim and Mcl-1 in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells by real-time PCR after AZD6244 and/or Nutlin3a treatment. Results indicated that AZD6244, Nutlin-3a or the combination minimally affected the mRNA expression levels of FOXO3a, Bim and Mcl-1. However, AZD-6244, Nutlin-3a and more so the combination enhanced mRNA levels of Puma (Figure 4A). The pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk reduced AZD6244/Nutlin-3a-induced apoptosis by suppressing caspase activation and concomitantly prevented the decrease in Mcl-1 levels, suggesting that Mcl-1 reduction was induced by caspase cleavage (Figure 4B). Further investigation of the cellular location of these proteins in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells demonstrated that combination treatment increased total FOXO3a protein expression in whole-cell (WCE) and cytosolic extract (CytE) but less in the nuclear fraction. Likewise, phospho-FOXO3a (at ser344 and ser425) was decreased in WCE and CytE, but less in NucE. The levels of Puma and Bim increased significantly in CytE and only moderately in NucE, while p53 protein increased in NucE (Figure 4C). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed those expression patterns of FOXO3a, Puma, and p53 in OCI/AML3 cells; i.e., up-regulation of FOXO3a and Puma protein levels occurred mainly in the cytoplasm, whereas p53 exhibited nuclear translocation after combination treatment with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a (Figure 4D). The expression levels of Puma and p53 were impressively higher in cells undergoing apoptosis (Figure 4D, arrows).

Figure 4.

The effect of combined treatment with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a on transactivation and location of apoptosis-related proteins in AML cells. (A) OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells were treated for 24 hours with AZD6244 plus Nutlin-3a (in 1:20 and 1:1 ratio, respectively, in OCI-AML3 and MOLM13 cells). DMSO only was used as a control (cont). The transcription levels of FOXO3a, Puma, Bim and Mcl-1 were measured using real-time PCR. The results are presented as the mean changes in mRNA levels from duplicate experiments. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. *, P < 0.05 and #, P < 0.01 vs. control groups. (B) Mcl-1 and cleaved-caspase-3 protein levels were measured by Western blot and cell apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry after 1 hour of pretreatment with pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-fmk, R&D System) and additional 23 hours treatment of AZD6244/Nutlin3a. (C) The levels of the indicated proteins were determined by measuring the whole-cell extract (WCE), cytoplasmic extract (CytE), and nuclear extract (NucE) fractions. EL, L, and S indicate extra-long, long, and short splice variants of Bim proteins, respectively. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, was used as loading control for the nuclear fraction, and tubulin was used as loading control for the cytoplasmic fraction. (D) The subcellular distribution of FOXO3a, Puma, and p53 proteins was determined by immunofluorescence staining and visualized by confocal microscopy. The secondary antibodies to FOXO3a and Puma were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), and the secondary anti-p53 antibody was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The arrows indicate apoptotic cells.

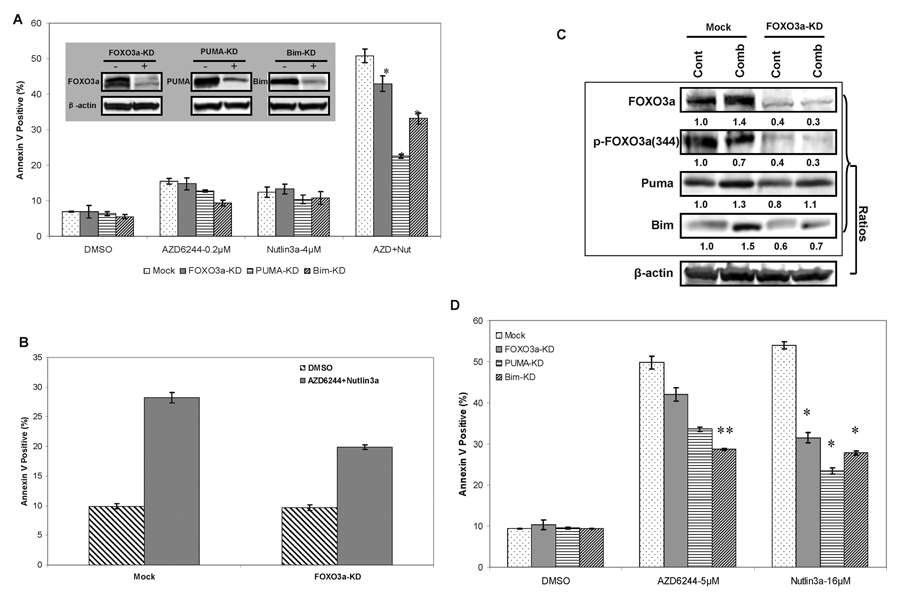

Knockdown of Puma and Bim rescues AML cells from apoptosis induced by AZD6244 and Nutlin3a

Since blockade of ERK and MDM2 signaling up-regulated protein levels of FOXO3a, Puma and Bim, we next determined which proteins played a key role in combination-mediated apoptosis. The expression of FOXO3a, Puma, or Bim was knocked-down using specific short interfering (si)RNAs in OCI/AML3 cells. Significant (>70%) suppression of the target protein levels was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 5A, insert panel). OCI/AML3 cells transfected with mock siRNA became apoptotic (50.8% ± 1.9%) after 24 hours of combination treatment. However, Puma knockdown significantly diminished the apoptosis induced by combined AZD624/Nutlin3a treatment (to 22% ± 0.6%), and knockdown of Bim moderately decreased apoptosis (to 33% ± 1.6%). Only a minor decrease was observed in FOXO3a-knockdown relative to control cells (Figure 5A). To reduce the potential nonspecific effects of FOXO3a knock-down, combination treatment was shortened to only 6 hours after transfection of cells with FOXO3a siRNA for 24 hours. Knockdown of FOXO3a partially diminished apoptosis induction (from 28 % ± 0.9 % to 20% ± 0.4%) by combined AZD6244/Nutlin3a treatment (Figure 5B), and this was associated with partial inhibition of induction of Puma and Bim proteins (Figure 5C). To further investigate the effects of knocking down these proteins on apoptosis induction by AZD6244 and Nutlin3a alone, higher concentrations of the inhibitors were used which would result in approximate 50% apoptosis in mock siRNA–transfected cells. The results showed that Nutlin3a-mediated apoptosis was significantly abrogated in the cells with knockdown of FOXO3a, Puma, or Bim proteins. However, AZD6244-mediated apoptosis was most diminished in Bim-knockdown, less so in Puma-knockdown cells (Figure 5D). These results suggested that Puma is a critical mediator of apoptosis induced by Nutlin3a and by the Nutlin3a/AZD6244 combination in p53 wild–type OCI/AML3 leukemia cells. In turn, Bim is likely a key regulator in AZD6244-induced apoptosis.

Figure 5.

(A) Effects of knock-down of the indicated proteins on AZD6244- and/or Nutlin3a-mediated AML cell apoptosis. OCI/AML3 cells were transiently transfected with FOXO3a, Puma and Bim siRNAs or mock control siRNA using Amaxa nucleofection. After 24 hours, AZD6244 (0.2 µM) and Nutlin3a (4 µM) or DMSO were added for additional 24 hours, and the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V–positive) cells was determined by flow cytometry. Data were generated from triplicate experiments. Insert panel showed basal levels of FOXO3a, Puma and Bim, which were determined by Western blot after 48 hours of transfection. (B) After transfection with FOXO3a or Mock siRNA for 24 hours, the OCI/AML3 cells were exposed to AZD6244 (1 µM) and Nutlin3a (12 µM) or DMSO for 6 additional hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was measured by flow cytometry, and (C) the expression levels of the indicated proteins were measured by immunoblotting. Data were generated from duplicate experiments. (D) OCI/AML3 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs for 24 hours, followed by treatment with AZD6244 (5 µM), Nutlin3a (16 µM), or DMSO for additional 24 hours. The percentage of annexin V–positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. Data represent triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.05 vs. mock control group.

Discussion

The detailed mechanisms of growth inhibition caused by simultaneous inhibition of MEK/MDM2 signaling pathways remain undetermined. It is well established that inhibition of cell proliferation by MEK inhibitors is mediated by G1 cell-cycle arrest. In this study, we have demonstrated synergistic p53-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation (BrdU incorporation) upon combined targeting of MEK/MDM2 signaling by AZD6244 and Nutlin3a in leukemia cells. Progression through the cell cycle is executed through serial steps controlled by key checkpoint proteins. During early/mid G1, cyclin D activates its associated CDKs (CDK4 and CDK6), promoting phosphorylation of Rb. In late G1 phase, the cyclin E/CDK2 heterodimeric complex mediates further phosphorylation of Rb and subsequent release of E2F which acts as a transcriptional activator by binding to sites on the promoters of genes essential for DNA synthesis(30). In turn, the "Cip/Kip" proteins p27Kip1 and p21Cip1 function as regulators of cell cycle progression at G1 by directly inhibiting G1 phase related checkpoint proteins and arresting cells in G1 phase. Notably, the combination treatment upregulated p53, p27Kip-1, downregulated G1 cell-cycle checkpoint proteins cyclin E/cdk2 complex, cyclin D1/cdk4 complex, cdc2, and suppressed phosphorylation of Rb. Growth-inhibitory effects of combined MEK/MDM2 blockade were independent of p16INK4a, one of the modulators of cyclin D1 expression (data not shown). In addition, p21 levels were modulated differently in OCI-AML3 and MOLM13 cells despite consistent growth inhibition observed in both cell types (Figure 2A), indicating that p21 is not the key protein responsible for the observed cell cycle arrest. Further studies are needed to precisely map the convergence point of cell cycle regulation by these two agents.

The limited induction of apoptosis by suppressing MEK has been reported(21) . Our present study demonstrated that AZD6244 at 0.2 nM concentration for 24 hours induced only modest apoptosis, but combined with Nutlin3a significantly induced apoptosis in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells, although suppression of phospho-ERK was almost at the same level (Figure 2B). This finding further supports the fact that suppression of ERK activation might not be sufficient for apoptosis induction in AML and optimized combination strategies need to be developed.

We have previously reported that the combination of MEK inhibitor PD98059 with MDM2 antagonist Nutlin3a synergistically induced apoptosis in human OCI/AML3 cells. This was at least in part attributed to the ability of PD98059 to antagonize p53-mediated p21 induction, triggered by Nutlin 3a, which abrogates p21-mediated apoptotic resistance(31). However, in the present study using second generation of MEK inhibitor AZD6244 plus Nutlin3a, modulation of p21 level did not parallel cell cycle arrest or apoptosis induction, and p21 levels in fact increased in MOLM13 cells after combination treatment (Figure 2A). In turn, we observed upregulation of BH3-only proteins Puma, Bim and downregulation of antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 associated with apoptosis induction (Figure 3A). This was associated with p53-dependent suppression of FOXO3a phosphorylation at both ser 344 and ser 425 sites and upregulation of the total levels of FOXO3a, a known transcriptional activator of Puma, Bim, and p27Kip-1 mRNA, (32–34).

FOXO3a signaling has been reported to be modulated by PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, in response to growth factor stimulation, via AKT-dependent phosphorylation of FOXO3a leading to its degradation in the cytoplasm(35). FOXO3a also is non-transcriptionally regulated by E2F-1 as its direct downstream target during neuronal apoptosis(36), which is independent of p53(37). However, in the present study, AZD6244 or Nutlin3a did not affect AKT phosphorylation or E2F-1 levels [Fig. 2B] implying alternative mechanisms involved in the regulation of FOXO3a. As such, FOXO3a was recently shown to be degraded through MDM2-mediated ubiquitination following direct phosphorylation by ERK at several sites (ser 294, ser 344, and ser 425).(38) In fact, our data showed that inhibition of phosphorylated ERK by targeting MEK/ERK signaling was associated with de-phosphorylation of FOXO3a at ser 344, and further de-phosphorylation of ser 344 and ser 425 by simultaneous targeting of MEK/MDM2 signaling. The latter might result from increased ubiquitination activity mediated by MDM2 which is likely induced via p53 in p53 wild type cells. Interestingly, total FOXO3a level increased in p53-knockdown cells after either single agent or combination treatment. We noted that basal expression of FOXO3a was also maintained at higher level in p53 knock down cells compared with their parental p53 wild-type cells. Lower basal level of MDM2 negatively correlated to the higher FOXO3a level, suggesting reduced degradation activation of MDM2 to FOXO3a protein may result in increasing of FOXO3a level. However, apoptosis induction in p53 knock down cells were lower than that in p53 wild type cells, and knocking down FOXO3a by shRNA only modestly reversed apoptosis induction. These suggest that FOXO3a itself is not the key mediator of apoptosis upon combined MEK/MDM2 blockade. Further studies are required to determine the regulation mechanism and precise role of FOXO3a in leukemic cell apoptosis.

Impressively, the transcription level of BH3-only protein Puma, which was originally identified as a p53-inducible gene (39), significantly increased (up to 12.4 and 8.3 folds in OCI/AML3 and MOLM13 cells, respectively) in wild-type p53 AML cells upon Nutlin or combined Nultin/AZD treatment, (Figure 4A), indicating p53-dependent upregulation of this BH3-only protein . However, Puma also increased upon combined drug exposure in p53 knockdown cells suggesting additional mechanisms of Puma upregulation. As such, FOXO3a has been reported to play an role in p53-independent Puma gene regulation(33). Most importantly, knockdown of Puma expression by shRNA dramatically reversed Nutlin3a- and AZD6244/Nutlin3a-induced cell apoptosis. Altogether, these findings point out to the critical role of Puma in apoptosis induction upon combined MEK/MDM2 blockade, possibly by modulating other Bcl-2 family members such as Bim, Mcl-1 and Bax.

The role of Bim in apoptosis induction of hematopoietic cells has been previously addressed in several experimental systems. It has been reported that inhibition of ERK1/2 activation is necessary and sufficient to promote substantial increase of Bim protein level by interfering ERK1/2-dependent degradation of Bim(40). Furthermore, blocking interaction of MDM2 and p53 may upregulate MDM2 level itself resulting in Bim accumulation. In fact, our data demonstrated that blocking either MEK or MDM2 upregulated Bim levels, and this effect was enhanced by the combined drugs treatment. No significant changes in mRNA Bim expression was noted, suggesting the upregulation more likely results from interfering with the protein degradation rather than activating its transcription. On the other hand, knock-down of Bim by shRNA only partially rescued AML cells from AZD/Nutlin-induced cell apoptosis, suggesting contributory but not central role of Bim in the lethality of combined MEK/MDM2 blockade

In addition, the effects of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Mcl-1 in apoptosis induction has been reported, which presents as a complex of Bim/Mcl-1, Puma/Mcl-1 or Bax/Mcl-1 for maintaining and regulating normal hematopoietic homeostasis physiologically. When apoptotic signals are received, upregulated Puma, Bim can displace Mcl-1 from Bak leading to Bak oligomerization, and then, Bim and Puma can interact with Bax causing its insertion into outer mitochondrial membrane, oligomerization and cytochrome c release. On the other hand, Mcl-1 protein itself can be regulated by transcription and/or E3 Ubiquitination degradation.(41) In addition, inhibition of Mcl-1 sensitized MEK inhibitor U0126-induced apoptosis in melanoma patients.(42) Our present data showed that blocking either MEK or MDM2 led to downregulation of Mcl-1 and upregulation of Bax, and the modulation was synergized by the combined drug treatment. That was more significant in OCL/AML3 cells which induced more apoptosis compared with MOLM13 cells. However, the decrease in Mcl-1 protein could be prevented by the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk, which only slightly reduced apoptosis induction, suggesting that Mcl-1 might be not crucial in AZD6244/Nutlin-3a-induced cell death.

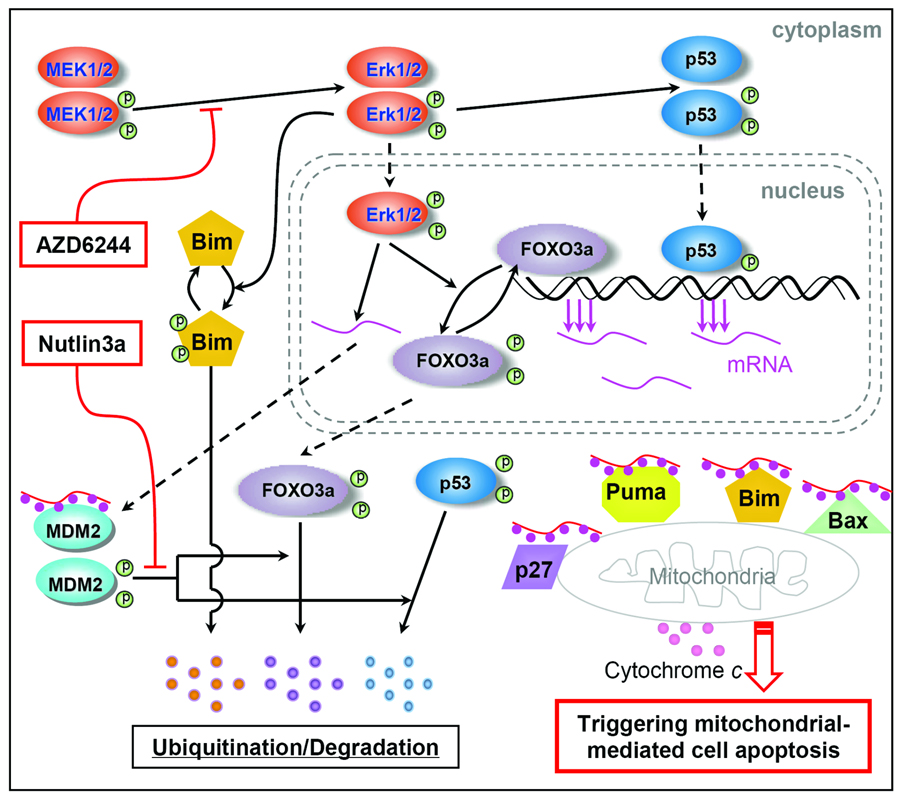

On the basis of these findings, we propose that the Bcl-2 family proteins Puma, Bim, Bax, and Mcl-1 rather than FOXO3a are key contributors to the proapoptotic effects in combined blockade of the MAPK and MDM2 signaling pathways in p53 wild-type AML. In fact, Puma and Bim can be directly up-regulated by p53 activation and ERK inhibition, respectively, and trigger mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in AML cells by associating with other Bcl-2 family proteins such as Bax and Mcl-1(42, 43). That may explain why knockdown of FOXO3a only is insufficient to abrogate apoptosis mediated by combined treatment with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a. However, knockdown of Puma and Bim resulted in protection of cells from AZD/Nutlin–induced cell death. This was further substantiated by our confocal microscopy data demonstrating dramatic upregulation of Puma but not of FOXO3a in early-stage apoptotic cells. Puma knockdown resulted in protection from apoptosis induction by high concentrations of Nutlin3a, whereas Bim knockdown significantly diminished the proapoptotic effects of high concentrations of AZD6244. Taken together, these findings indicate that the level of Puma is regulated primarily via Mdm2/p53 axis, while Bim protein expression depends on MAPK activation status. FOXO3a facilitated the upregulation of Puma and Bim expression via either transcription or degradation.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the small-molecule MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 has a profound cytostatic effect on AML cells with constitutive activation of MEK/ERK signaling. In turn, cytotoxic effects of MEK inhibition are synergistically induced by targeting MDM2-p53 axis with Nutlin3a. Mechanistically, Puma and Bim were identified as critical mediators of apoptosis induced by simultaneous blockade of MEK and MDM2 signaling, which is partially mediated by transcriptional activation of FOXO3a. These pleiotropic effects are summarized in a model illustrated in Figure 6. Our findings for the first time identify Puma and Bim as factors in apoptosis induced by combined AZD6244 and Nutlin3a treatment in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that combinatorial targeting of MEK and MDM2 with AZD6244 and Nutlin3a has potential as a novel mechanism-based therapeutic strategy for AML.

Figure 6.

Mechanisms of synergistic apoptosis induction via combined blockade of MAPK and MDM2 signaling pathways in AML cells. FOXO3a and p53 are transcription factors that modulate levels of the proapoptotic proteins Puma, Bim, Bax, and p27. This schematic diagram illustrates an interaction of MEK/ERK signaling and an MDM2–p53 feedback loop and their interface with ubiquitination/ degradation of FOXO3a and p53 proteins. FOXO3a and p53 are the main transcription factors regulating the levels of Puma, Bim, Bax, p27 proteins (44–48). ERK activation triggers phosphorylation of FOXO3a at several sites (ser294, ser344, and ser425) (38) and promotes phosphorylation of Bim (49). MAPK signaling is further involved in maintaining the dynamic equilibrium of the MDM2–p53 feedback loop by modulating the phosphorylation level of p53 and the nuclear export of MDM2 mRNA (50, 51). In turn, MDM2 exerts regulation of FOXO3a and p53 levels by ubiquitination-mediated degradation (4, 38). Simultaneous blockade of MEK/ERK and MDM2 signaling contributes to the mitochondrial-mediated cell apoptosis by up-regulating FOXO3a and p53 levels and transactivating Puma, Bim, and other proapoptotic proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenjing Chen for the valuable assistance in the collection of patients’ clinical information and Karen Phillips for editorial assistance.

Grant support: National Institutes of Health CA55164, CA016672, CA100632 (M.A.); Leukemia SPORE Career Development Award CA100632 (W.Z.); and partial funding by AstraZeneca (M.A).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The study sponsor had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Clinical Trials (2007). http://www clinicaltrials gov 2008;Accessed 6-April-08.

Reference List

- 1.Ricciardi MR, McQueen T, Chism D, et al. Quantitative single cell determination of ERK phosphorylation and regulation in relapsed and refractory primary acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1543–1549. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornblau SM, Womble M, Qiu YH, et al. Simultaneous activation of multiple signal transduction pathways confers poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2358–2365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seliger B, Papadileris S, Vogel D, et al. Analysis of the p53 and MDM-2 gene in acute myeloid leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 1996;57:230–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1996.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell. 1992;70:523–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMurray HR, Sampson ER, Compitello G, et al. Synergistic response to oncogenic mutations defines gene class critical to cancer phenotype. Nature. 2008;453:1112–1116. doi: 10.1038/nature06973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blalock WL, Moye PW, Chang F, et al. Combined effects of aberrant MEK1 activity and BCL2 overexpression on relieving the cytokine dependency of human and murine hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:1080–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moye PW, Blalock WL, Hoyle PE, et al. Synergy between Raf and BCL2 in abrogating the cytokine dependency of hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:1060–1079. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr AH, James JA, Smith MA, Willson C, Court EL, Smith JG. An investigation of the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 in acute myeloid leukemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:86–89. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milella M, Konopleva M, Precupanu CM, et al. MEK blockade converts AML differentiating response to retinoids into extensive apoptosis. Blood. 2007;109:2121–2129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunghi P, Tabilio A, Dall'Aglio PP, et al. Downmodulation of ERK activity inhibits the proliferation and induces the apoptosis of primary acute myelogenous leukemia blasts. Leukemia. 2003;17:1783–1793. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milella M, Kornblau SM, Estrov Z, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the MEK/MAPK signal transduction module in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:851–859. doi: 10.1172/JCI12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Konopleva M, Ruvolo VR, et al. Sorafenib induces apoptosis of AML cells via Bim-mediated activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Leukemia. 2008;22:808–818. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huynh H, Soo KC, Chow PK, Tran E. Targeted inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase pathway with AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:138–146. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tai YT, Fulciniti M, Hideshima T, et al. Targeting MEK induces myeloma-cell cytotoxicity and inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Blood. 2007;110:1656–1663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Davies BR, Logie A, McKay JS, et al. AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), a potent inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2 kinases: mechanism of action in vivo, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship, and potential for combination in preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2209–2219. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ball DW, Jin N, Rosen DM, et al. Selective growth inhibition in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4712–4718. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA, et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1576–1583. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haass NK, Sproesser K, Nguyen TK, et al. The mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) induces growth arrest in melanoma cells and tumor regression when combined with docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:230–239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Konopleva M, Schober W, McQueen T, Andreeff M. MEK Inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) Induces Cell Growth Arrest and Synergizes with Nutlin-3a-mediated Cell Death by Upregulating p53 and PUMA Levels in AML (ASH Abstract) Blood. 2008;110:201a. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milella M, Precupanu CM, Gregorj C, et al. Beyond single pathway inhibition: MEK inhibitors as a platform for the development of pharmacological combinations with synergistic anti-leukemic effects. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2779–2795. doi: 10.2174/1381612054546842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima K, Konopleva M, Samudio IJ, et al. MDM2 antagonists induce p53-dependent apoptosis in AML: implications for leukemia therapy. Blood. 2005;106:3150–3159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kojima K, Konopleva M, Samudio IJ, Ruvolo V, Andreeff M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition enhances nuclear proapoptotic function of p53 in acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3210–3219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter BZ, Mak DH, Schober WD, et al. Triptolide sensitizes AML cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via decrease of XIAP and p53-mediated increase of DR5. Blood. 2008;111:3742–3750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clodi K, Kliche K-O, Zhao S, et al. Cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine correlates with the stage of fludarabine-induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and expression of apoptosis-regulating genes. Cytometry. 2000;40:19–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(20000501)40:1<19::aid-cyto3>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, McQueen T, Schober W, Rassidakis G, Andreeff M, Konopleva M. Leukotriene B4 receptor inhibitor LY293111 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human anaplastic large-cell lymphoma cells via JNK phosphorylation. Leukemia. 2005;19:1977–1984. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konopleva M, Zhang W, Shi YX, et al. Synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces growth arrest in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:317–328. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao L, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Evaluation of combination chemotherapy: integration of nonlinear regression, curve shift, isobologram, and combination index analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7994–8004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson DG, Schneider-Broussard R. Role of E2F in cell cycle control and cancer. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d447–d448. doi: 10.2741/a291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:639–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J. FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:613–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You H, Pellegrini M, Tsuchihara K, et al. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1657–1663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong S, Kang S, Lonial S, Khoury HJ, Viallet J, Chen J. Targeting 14-3-3 sensitizes native and mutant BCR-ABL to inhibition with U0126, rapamycin and Bcl-2 inhibitor GX15-070. Leukemia. 2008;22:572–577. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowak K, Killmer K, Gessner C, Lutz W. E2F-1 regulates expression of FOXO1 and FOXO3a. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giovanni A, Keramaris E, Morris EJ, et al. E2F1 mediates death of B-amyloid-treated cortical neurons in a manner independent of p53 and dependent on Bax and caspase 3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11553–11560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang JY, Zong CS, Xia W, et al. ERK promotes tumorigenesis by inhibiting FOXO3a via MDM2-mediated degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:138–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ley R, Balmanno K, Hadfield K, Weston C, Cook SJ. Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of the BH3-only protein, Bim. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18811–18816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akgul C. Mcl-1 is a potential therapeutic target in multiple types of cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1326–1336. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8637-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang YF, Jiang CC, Kiejda KA, Gillespie S, Zhang XD, Hersey P. Apoptosis induction in human melanoma cells by inhibition of MEK is caspase-independent and mediated by the Bcl-2 family members PUMA, Bim, and Mcl-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4934–4942. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalak EM, Villunger A, Adams JM, Strasser A. In several cell types tumour suppressor p53 induces apoptosis largely via Puma but Noxa can contribute. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1019–1029. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran H, Brunet A, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. The many forks in FOXO's road. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.172.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Pals C, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1 modulates cytokine-dependent transcriptional regulation of p27(KIP1) Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9138–9148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9138-9148.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Lammers JW, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by the forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vousden KH. Apoptosis. p53 and PUMA: a deadly duo. Science. 2005;309:1685–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1118232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meulmeester E, Jochemsen AG. p53: a guide to apoptosis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:87–97. doi: 10.2174/156800908783769337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weston CR, Balmanno K, Chalmers C, et al. Activation of ERK1/2 by deltaRaf-1:ER* represses Bim expression independently of the JNK or PI3K pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:1281–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milne DM, Campbell DG, Caudwell FB, Meek DW. Phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9253–9260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phelps M, Phillips A, Darley M, Blaydes JP. MEK-ERK signaling controls Hdm2 oncoprotein expression by regulating hdm2 mRNA export to the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16651–16658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.