Abstract

Type VI secretion systems (T6SSs) have recently been recognized as potential virulence determinants of many Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Although mechanistic studies are lacking, T6SS-dependent phenotypes can be observed in various animal models of infection. Presumably translocation of T6SS effectors into target cells is involved in virulence, but few such effectors have been identified. A hallmark of T6SS function is the in vitro secretion of Hcp and VgrG proteins, which are thought to form part of an extracellular secretion apparatus. One well-characterized effector domain is the C-terminal actin cross-linking domain (ACD) of the VgrG-1 protein, constitutively secreted by the T6SS of Vibrio cholerae strain V52. Previous work indicated that translocation of VgrG-1 occurred only after endocytic uptake of bacteria into host cells. VgrG-1-induced actin cross-linking impaired phagocytic activity of host cells, eventually causing cell death. To determine whether V. cholerae T6SS is functional during animal infection, derivatives of V52 were used to infect infant mice. In this infection model a diarrheal response occurred, and actin cross-linking could be detected. These host responses were dependent on a functional T6SS and on the ACD of VgrG-1. Gene expression and histologic studies showed innate immune activation and immune cell infiltration in the intestinal lumen. The T6SS-dependent inflammatory response was also associated with increased recovery of V. cholerae from the intestine. We conclude that the T6SS of V52 induces an inflammatory diarrhea that facilitates replication of V. cholerae within the intestine.

Keywords: innate immunity, VgrG, virulence effector, ACD, MARTX

Vibrio cholerae is a Gram-negative pathogen that causes diarrheal disease ranging from cholera to mild gastroenteritis. Some V. cholerae virulence factors are well characterized, such as cholera toxin and toxin coregulated pilus (1). The contributions of other virulence factors to V. cholerae pathogenesis are beginning to be elucidated (2, 3), and one putative accessory virulence factor is the type VI secretion system (T6SS).

T6SSs are encoded by conserved gene clusters present in many Gram-negative pathogens, and functional systems typically secrete Hcp and VgrG orthologs (4, 5). The components constituting this multiprotein secretion complex are beginning to be defined. On the basis of work in several organisms, the T6SS IcmF ortholog seems to be a central scaffolding protein that interacts with itself, the T6SS DotU ortholog, and a T6SS-encoded outer membrane lipoprotein (6–8). In V. cholerae, T6SS proteins VipA and VipB form a tubular structure that is dissociated by ClpV protein in an ATP-dependent manner (9), which could be required for biogenesis of a functional secretion complex. This interaction could also be involved in recruitment to the T6SS core structure because the T6SS IcmF ortholog and a VipA ortholog interact with each other, and ClpV can be recruited to discrete foci at the inner membrane (9, 10). Although these findings are from studies in different bacterial species, the overall interactions are likely maintained to form a conserved secretion complex that transports the T6SS substrates, Hcp and VgrG. These proteins are mutually required for secretion and are thought to form part of an extracellular secretion apparatus (5, 11). The structures of Hcp and VgrG proteins resemble components of T4 bacteriophage tail tube and tail spike, respectively, which are required to puncture host membrane in the context of phage infection (4, 12,m–14). Additionally, many VgrG proteins contain C-terminal extensions, some of which possess effector function, such as the actin cross-linking domain (ACD) of VgrG-1 in V. cholerae (11). This domain covalently cross-links actin monomers by catalyzing intermolecular isopeptide bonds (15). After uptake of bacteria into macrophage cell lines, VgrG-1 or its ACD domain was translocated into the host cell cytosol to cross-link cellular actin, thereby impairing subsequent phagocytic function (11, 16, 17). An ACD deletion mutant was functional for secretion and translocation of a heterologous C-terminal reporter into target cells, indicating that the structural apparatus function and actin cross-linking effector function are dissociable (16).

Virulence associated with T6SS has been evaluated in various animal models of infection, including lethality assays and colonization models. Genes within Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cenocepacia T6SS loci were identified in transposon mutagenesis screens for attenuated colonization in a rat chronic lung infection model (18, 19). Consistent with a role in chronic infection with P. aeruginosa, sera from cystic fibrosis patients were reactive to Hcp, and sputum from a chronically infected patient contained Hcp protein (4). Compound deletion of the remaining two T6SS loci attenuates P. aeruginosa virulence in murine lung and burn infection models (20). Catfish that were exposed to Edwardsiella itaculari produced antibodies that are reactive to orthologs of VipA, VipB, and Hcp, and mutants in these and other T6SS genes are attenuated in virulence during infections in fish (8, 21). Intraperitoneal infections of hamsters were lethal when inoculated with wild-type Burkholderia mallei, whereas T6SS mutants were nonlethal (22). Additionally, sera from B. mallei-infected mice, a naturally infected horse, and an infected human patient were all reactive to purified B. mallei ortholog of Hcp (22). A recent study showed that B. mallei expresses T6SS-1 after uptake into RAW 264.7 macrophages, and a defect in T6SS impaired intracellular growth and actin-based motility (23).

Although these studies implicate T6SS in virulence in animal models, a mechanistic understanding of T6SS function in vivo is lacking. The V. cholerae T6SS effector VgrG-1 and its ACD domain is clearly required for its cytotoxic effect on Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae (5, 16). A putative Edwardsiella tarda effector is EvpP, which is encoded in the T6SS gene cluster and has orthologs in several other E. tarda strains and an Aeromonas hydrophila strain (8, 24). Secretion of EvpP requires T6SS, Hcp ortholog EvpC, and VgrG ortholog EvpI, whereas deletion of EvpP does not affect secretion of EvpC and EvpI. EvpP mutants are attenuated in fish models of infection and have been associated with invasion of a fish epithelial cell line (24). A. hydrophila clinical isolate SSU encodes a VgrG C-terminal effector domain. This strain required T6SS for virulence in mouse lethality assays, and immunization with purified Hcp protected against lethal infection (25). This T6SS caused contact-dependent host cell rounding and could translocate a VgrG homolog that contains an effector domain homologous to VIP-2, an insecticidal toxin with ADP ribosylation activity specific for actin (26). Catalytic activity was demonstrated in vitro, and transfection of this domain caused disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, cell rounding, and apoptosis.

Here we evaluated the contribution to virulence of the V. cholerae T6SS in the context of a mammalian intestinal infection. Using an infant mouse model, we found that the T6SS constitutive strain V52 can induce a fluid accumulation response that has hallmarks of inflammatory diarrhea. This phenotype is characterized by changes in intestinal fluid accumulation, detection of cellular infiltration in the intestinal lumen, and changes in gene expression consistent with inflammation. Translocation of VgrG-1 occurred in this model because cross-linked actin was detected in intestinal cell lysates, and the ACD effector domain was required for all T6SS-dependent phenotypes in this infection model. This work demonstrates that T6SS-mediated translocation occurs in vivo and is associated with an acute host response to a specific effector, consistent with a role for T6SS as a virulence factor used by some strains of V. cholerae.

Results

V. cholerae T6SS Elicits a Fluid Accumulation Response and Cross-Links Actin in Vivo.

To evaluate V. cholerae T6SS function in vivo, the suckling or “infant” mouse model for cholera was used. Five-day-old infant mice were infected with an inoculum of 5 × 109 of various mutant derivatives of V. cholerae V52 (Table 1). Some strains elicited a diarrheal response 3 to 4 h after infection. This response was quantified by determining fluid accumulation ratios (Fig. 1), as defined by the ratio of the weight of dissected intestine and the remaining body mass. Surprisingly, this response did not require the two known toxins encoded by rtxA or ctxAB, because fluid accumulation is still observed in infections with ATM-1 (ΔrtxA) and ATM-13 (ΔctxAB). However, this fluid accumulation response was abolished in infections with strains carrying a deletion of icmF ortholog vasK, as observed with strains ATM-2 and ATM-3 (Fig. 1A). Additional T6SS mutant strains, ATM-14 (ΔvgrG-2) and ATM-6 (vgrG-1ΔACD), were tested and also failed to produce a fluid accumulation response (Fig. 1B). Strains that lack vasK or vgrG-2 are unable to secrete T6SS substrates (11). Although strain ATM-6 is competent for secretion of T6SS substrates (16), it lacks the ACD, suggesting that this effector domain is required for eliciting this fluid accumulation response.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

Fig. 1.

Fluid accumulation elicited by V. cholerae T6SS. Fluid accumulation was determined by calculating ratio of intestinal weight to remaining body weight. (A) controls for RtxA (ATM-1) and CtxAB (ATM-13) and (B) additional T6SS mutants. Groups marked with asterisks have values that are significantly higher than unmarked groups (Student’s t test, P < 0.05). Bars indicate mean values for each group. Four to seven mice were used per group. Full genotypes are listed in Table 1.

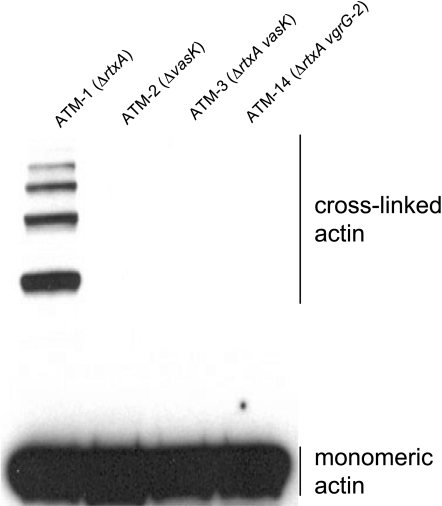

Translocation of the VgrG-1 protein into cultured mammalian cells can be monitored by detection of cross-linked actin, the enzymatic product of the ACD (11, 16). Remarkably, intestines from mice infected with ATM-1 contained detectable cross-linked actin (Fig. 2). After infections with nonsecreting T6SS mutants ATM-3 (ΔvasK) and ATM-14 (ΔvgrG-2), actin cross-linking could not be detected. These strains express wild-type levels of VgrG-1 but cannot secrete it. This suggests that VgrG-1 released by bacterial lysis cannot access and cross-link host cell actin and that the actin cross-linking observed is likely due to bona fide translocation of VgrG-1 into host cells by an intact T6SS. Unexpectedly, cross-linked actin was not detected after infection with ATM-2 (ΔvasK), which contains an intact rtxA gene and is able to robustly cross-link actin in tissue culture cells (16). These data suggest that for strain V52, the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX (MARTX) toxin encoded by rtxA is not significantly active in this infant mouse model of infection. Alternatively, T6SS and MARTX could be expressed at temporally distinct phases of infection. These data indicate that the T6SS of strain V52 is essential for inducing a fluid accumulation phenotype in this animal model and that the ACD effector domain of VgrG-1 is the likely critical effector molecule mediating this response in vivo.

Fig. 2.

In vivo actin cross-linking. Infant mice were infected for 4 h with various V52 strains of ΔhlyA hapA background. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from harvested intestines by passage through cell strainers and collected by centrifugation. Samples were analyzed by Western blot against actin.

Cellular Infiltration and Changes in Host Gene Expression Implicate an Inflammatory Response.

Intestinal inflammation is well known to induce diarrheal responses through a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms, including production of prostaglandins and host tissue injury (27). Accordingly, we evaluated the histologic changes that occurred in this infection model to determine whether they were consistent with inflammation. H&E-stained sections of intestines from mice infected with various V52 derivative strains were analyzed and scored blindly by a pathologist. In sections from mice infected with strain ATM-1, cellular infiltrates were seen in the lumen of the small intestine, whereas mock-infected, ATM-6 (ΔACD)-infected, and ATM-14 (ΔvgrG-2)-infected mice had a normal histologic appearance (Fig. 3). Typically in ATM-1-infected mice, no intestinal injury and some cellular infiltrate were observed in the proximal small intestine, whereas detectable intestinal injury and most of the cellular infiltration occurred in the distal small intestine. These infiltrating cells appeared to be monocytic, with few polymorphonuclear cells. Infiltrating cells within the intestinal lumen suggest that the fluid accumulation response could be due to inflammation.

Fig. 3.

Histology of infant mouse small intestine. Infant mice were infected with various V52 strains of ΔrtxA hlyA hapA background. Intestinal sections were stained with H&E (40×). Sections are from (A) mock-infected mice, (B and C) T6SS mutant-infected mice, and (D) ATM-1 infected mice.

Microarray analysis was performed to determine whether changes in host gene expression occurred that were consistent with inflammation. Whole-transcriptome analysis was performed on intestinal tissue from mock-infected, ATM-1-infected, and ATM-6 (ΔACD)-infected mice. After statistical significance was assessed using the SAM (statistical analysis of microarrays) algorithm and a 2-fold change cutoff was imposed, 106 genes were more highly expressed, whereas 13 genes had lower expression in ATM-1-infected mice compared with mock-infected mice (Fig. 4). Generally, expression of these genes in the intestines of ATM-6-infected mice was intermediate between mock-infected and ATM-1-infected mice (Table S1). Although this host response reflects changes in gene expression in intestinal cells, the changes in ATM-1-infected mice would also include expression of genes in infiltrating cells. The more highly expressed genes were enriched for the biologic processes of inflammation, wound healing, and angiogenesis, as determined via the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) bioinformatics resource (28, 29).

Fig. 4.

Heat map of differentially expressed genes. Significant genes were determined by the SAM algorithm with a 2-fold change cutoff. (A) Genes with higher expression and (B) genes with lower expression are shown. Values depicted are log2 expression values from three independent experiments.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes shows that there was innate immune activation in both ATM-1- and ATM-6-infected mice compared with mock-infected mice. Genes involved in innate immune signaling (Nfkb2), immune cell recruitment (Ccl20, Cxcl10, and Cxcl16), direct antimicrobial activity (Nos2, Duox2, and Reg3g), and the acute-phase marker serum amyloid A 3 (Saa3) all had at least 2-fold higher expression in infected mice over mock-infected mice. This could reflect nonspecific interaction between V. cholerae pathogen-associated molecular patterns and Toll-like receptors found on epithelial cells and gut-associated lymphoid tissue. These interactions are apparently tolerated in ATM-6-infected mice, in that inflammation is not induced. However, in infections with ATM-1, clear inflammation was apparent, indicated by the luminal cellular infiltrate. This difference in host pathobiologic phenotype is reflected by higher expression of many inflammation genes in ATM-1- vs. ATM-6-infected mice.

Additional host genes were also more highly expressed in ATM-1-infected mice, but expression of these genes in ATM-6-infected mice was below the 2-fold cutoff. These included inflammation mediator prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2 or COX-2), cytokines (Il1a and Il1b), and chemokines (Ccl12 and Cxcl5). Secretion of cytokines and signaling through NF-κB activate innate immune responses to defend against microbes by recruitment of infiltrating immune cells and production of antimicrobial factors. Cell adhesion molecule gene Icam1 was more highly expressed in ATM-1-infected mice, and this receptor is associated with leukocyte migration. ATM-1 induced higher expression of genes that regulate inflammation, including Nfkbia, Atf3, Socs3, and zinc finger proteins tristertrapolin (Zfp36) and Zc3h12a, which destabilize mRNA transcripts of proinflammatory cytokines (30–33). This is consistent, because during activation of inflammation there is also concomitant negative regulation that dampens the immune response and aids in resolution of inflammation.

Genes encoding proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, IFN-γ-induced chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10), bacteriostatic siderophore-sequestering protein lipocalin 2 (34), and inflammation-associated matrix metalloproteinase MMP-3 (35) were chosen for verification by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5). In addition to expression of these genes in ATM-1- and ATM-6-infected mice, expression in mice infected with ATM-3 (ΔvasK) and ATM-14 (ΔvgrG-2) was examined. The level of expression of these host genes was significantly elevated in ATM-1-infected mice compared with mice infected with mutants deficient in either the ACD or T6SS. These data confirm that the ACD and V. cholerae T6SS are essential mediators of inflammation in this infection model.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative PCR verification of differentially expressed genes. Relative expression was calculated by normalization to GAPDH expression and then normalization to mock-infected expression. Values given are means ± SD of biologic triplicates.

Recovery of V. cholerae from the Small Intestine Is Enhanced by Inflammation.

Although recovery of ATM-1 and T6SS mutant strains was similar at early time points after infection before diarrheal symptoms occur (Fig. S1), significant differences in colonization were apparent after overnight infections (Fig. 6). To determine whether T6SS-induced inflammation facilitates recovery of V. cholerae from the small intestine, 4-h-long preinfections were performed with ATM-15 (ATM-1ΔlacZ) or ATM-16 (ATM-6ΔlacZ), followed by infection with ATM-1 or ATM-6 (ΔACD) (Fig. 6). Whereas preinfection with ATM-16 had no effect on recovery of secondarily inoculated ATM-6, preinfection with ATM-15 significantly increased recovery of ATM-6 after overnight infection. Preinfection with either ATM-15 or ATM-16 had no effect on recovery of ATM-1. Thus, ATM-15 enhanced the recovery of ATM-6, indicating that the T6SS-mediated inflammation induced by ATM-15 likely enhances survival and/or replication of V. cholerae within the gut. Like cholera toxin, the inflammatory diarrhea induced by strains of V. cholerae expressing T6SS might also aid in dissemination of the organism to new hosts through purging of infected intestinal fluids by disease victims.

Fig. 6.

Colony forming units (CFU) recovered from small intestine of infant mice after overnight infection. Groups preinfected for 4 h with ATM-15 (ATM-1ΔlacZ) or ATM-16 (ATM-6ΔlacZ) are indicated. Bars represent geometric means for each group. Four to five mice were used per infection group. Asterisks indicate groups with significantly higher means than unmarked groups (Mann-Whitney test, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Virulence factors such as toxins and protein secretions systems can deliver toxic “effector” domains to host cells. These virulence determinants are reasonably attributed with the pathophysiologic effects induced in host animals after infection by the pathogens encoding them. However, relatively few examples exist in which the biochemical action of an effector domain can be demonstrated in host tissues during infection independently of secondary host responses to these virulence factors. Here we report the direct detection of biochemical effector function during host infection and its correlation with pathophysiologic outcomes for the host. Specifically, translocation of VgrG-1 by V. cholerae T6SS into target cells during infection could be detected by virtue of the well-characterized actin cross-linking activity of its ACD. This biochemical event correlates with fluid accumulation, massive cellular infiltration, and finally altered host gene expression that is fully consistent with inflammatory diarrhea. Studies of quorum-sensing regulation of V. cholerae virulence factors show that T6SS is expressed at high cell density (36, 37), which could account for the large inoculum required to clearly observe T6SS-dependent pathology by V52. This suggests that V. cholerae T6SS expression might occur late in infection when inflammatory diarrhea could facilitate further replication and dissemination of the organism. Although the disease cholera is characteristically considered noninflammatory, some V. cholerae strains and live vaccine prototypes induce inflammatory diarrheas in human subjects (38). The data presented here suggest that the well-conserved T6SS of V. cholerae may also contribute to the inflammatory component of diarrheas associated with this organism.

Given the cell biologic requirements for VgrG-1 translocation, initiation of inflammation could occur after transcytosis by a variety of several cell types, including as dendritic cells, Peyer’s patch M cells (39), or even by epithelial cells (40). Although it is not clear how cross-linked actin in host cells could contribute to an inflammatory response, many cellular functions could be perturbed, and intracellular surveillance pathways could be activated. After induction of inflammation, mediators can induce fluid secretion and increase the permeability of the epithelium by loosening tight junctions, allowing immune cells infiltration and interstitial fluid to leak into the intestinal lumen. Immune cell infiltration typically includes recruitment of phagocytic cells, which represent another pool of cells that are susceptible to T6SS translocation and actin cross-linking. These phagocytic cells could be another source of cytokines and tissue damaging agents, which could amplify the inflammatory response. We showed here that T6SS-mediated inflammation also facilitates recovery of V. cholerae from the small intestine, despite the presence of infiltrating immune cells and higher expression of antimicrobial molecules. Many of the infiltrated inflammatory cells could contain cross-linked actin and thus be impaired for phagocytic function. It is noteworthy that some enteric pathogens can exploit this host process and benefit from intestinal inflammation (41). In these circumstances, inflammation allows the pathogens to overcome host mechanisms that limit colonization, such as disruption of commensal bacteria or increasing nutrient and oxygen availability (42). These mechanisms could account for the increased number of V. cholerae recovered after induction of T6SS-mediated inflammation. It is also worth noting that reactogenic diarrheas inducing by nontoxigenic V. cholerae vaccine prototypes apparently involves intestinal inflammation elicited by innate immune agonists such as flagellins (43).

By studying T6SS function in vivo, we were able to detect processes that might also occur in a natural infection. Although the pathogenic mechanism observed in this animal model could contribute to virulence in strains with constitutive T6SS, the role of T6SS in other V. cholerae strains is not so clear and may be obscured in vivo by the predominant effects of other virulence factors. Nonetheless, the well-conserved T6SS locus of V. cholerae is present in the majority of V. cholerae strains, suggesting that this factor might be an early “core virulence determinant” for the species. If so, the ability of T6SS to alter host pathophysiology may have contributed to the evolutionary process that led to acquisition of accessory virulence determinants, such as TCP and cholera toxin, and thus to the emergence of the highly successful pathogenic clones of V. cholerae that occur in the biosphere today.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

Some V. cholerae V52 strains are previously described (16), and new strains were constructed by previously described methods (17, 44, 45). All strains were maintained at −70 °C in glycerol stocks and cultured in LB supplemented with 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C.

Infant Mouse Infections.

Infant mouse infections were approved by the Harvard Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Five-day-old CD1 mice were weaned for 2 to 3 h, inoculated perorally with 5 × 109 V. cholerae, and maintained at 30 °C for 4 h. Some mice were then infected with a second inoculum and maintained at 30 °C for an additional 16–18 h. Small intestines were then harvested, homogenized, and plated for enumeration of colony forming units.

Fluid Accumulation.

For determination of fluid accumulation at 4 h, dissected intestines and remaining body mass were weighed. Fluid accumulation ratios were calculated by dividing the weight of the intestine by the weight of the remaining body mass.

Actin Cross-Linking.

After 4-h infections, single-cell suspensions were obtained by passage of harvested intestines through 40-μM cell strainers. Pelleted cells were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, boiled, sonicated, and centrifuged before analysis by Western blot with α-actin polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Histology.

After infection, intestines were coiled, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and processed for H&E staining. Images were acquired with a Nikon 80i upright equipped with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-Fi1 color camera.

RNA Isolation.

Dissected intestines were homogenized in TriReagent (Invitrogen), pooled in groups of five, and frozen at −80 °C until isolation of total RNA according to the manufacture’s instructions. RNA samples were further purified using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) before quantitative PCR and microarray analysis.

Microarrays and Bioinformatics.

Purified RNA was processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions for sample preparation, hybridization, washing, and scanning for Affymetrix Mouse Gene WT 1.0 arrays. Signal intensity was normalized between arrays, and log2 intensity values were calculated using the robust multichip average algorithm. Differentially expressed genes were determined by using the SAM algorithm with a 2-fold change cutoff and the 90% percentile false discovery rate set to 0. Overrepresentation of genes involved in inflammation (P = 2.4 × 10−10) was determined by bioinformatics analysis via DAVID (28, 29). Microarray data were deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus database.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

cDNA was synthesized with Omniscript kit (Qiagen) and diluted for quantitative PCR reactions with SYBR green and ROX mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method, with normalization of individual samples to GAPDH expression and normalization within infection groups to values of mock-infected mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI-18045 and AI-026289.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Database deposition: The microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE19946).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0915156107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Faruque SM, Albert MJ, Mekalanos JJ. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1301–1314. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1301-1314.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivier V, Haines GK, 3rd, Tan Y, Satchell KJ. Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5035–5042. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam VC, Serruto D, Dziejman M, Brieher W, Mekalanos JJ. A type III secretion system in Vibrio cholerae translocates a formin/spire hybrid-like actin nucleator to promote intestinal colonization. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mougous JD, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312:1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pukatzki S, et al. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschtgen MS, Bernard CS, De Bentzmann S, Lloubès R, Cascales E. SciN is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for type VI secretion in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7523–7531. doi: 10.1128/JB.00945-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma LS, Lin JS, Lai EM. An IcmF family protein, ImpLM, is an integral inner membrane protein interacting with ImpKL, and its walker a motif is required for type VI secretion system-mediated Hcp secretion in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4316–4329. doi: 10.1128/JB.00029-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng J, Leung KY. Dissection of a type VI secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1192–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bönemann G, Pietrosiuk A, Diemand A, Zentgraf H, Mogk A. Remodelling of VipA/VipB tubules by ClpV-mediated threading is crucial for type VI protein secretion. EMBO J. 2009;28:315–325. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mougous JD, Gifford CA, Ramsdell TL, Mekalanos JJ. Threonine phosphorylation post-translationally regulates protein secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:797–803. doi: 10.1038/ncb1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanamaru S, et al. Structure of the cell-puncturing device of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 2002;415:553–557. doi: 10.1038/415553a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pell LG, Kanelis V, Donaldson LW, Howell PL, Davidson AR. The phage lambda major tail protein structure reveals a common evolution for long-tailed phages and the type VI bacterial secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4160–4165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900044106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leiman PG, et al. Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4154–4159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudryashov DS, et al. Connecting actin monomers by iso-peptide bond is a toxicity mechanism of the Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18537–18542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma AT, McAuley S, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ. Translocation of a Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion effector requires bacterial endocytosis by host cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satchell KL. Bacterial martyrdom: phagocytosis disabled by type VI secretion after engulfing bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:213–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potvin E, et al. In vivo functional genomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for high-throughput screening of new virulence factors and antibacterial targets. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1294–1308. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt TA, Kooi C, Sokol PA, Valvano MA. Identification of Burkholderia cenocepacia genes required for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4010–4022. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4010-4022.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesic B, Starkey M, He J, Hazan R, Rahme LG. Quorum sensing differentially regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa type VI secretion locus I and homologous loci II and III, which are required for pathogenesis. Microbiology. 2009;155:2845–2855. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.029082-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore MM, Fernandez DL, Thune RL. Cloning and characterization of Edwardsiella ictaluri proteins expressed and recognized by the channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus immune response during infection. Dis Aquat Organ. 2002;52:93–107. doi: 10.3354/dao052093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schell MA, et al. Type VI secretion is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia mallei. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1466–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burtnick MN, Deshazer D, Nair V, Gherardini FC, Brett PJ. Burkholderia mallei cluster 1 type VI secretion mutants exhibit growth and actin polymerization defects in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2010;78:88–99. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00985-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, et al. Edwardsiella tarda T6SS component evpP is regulated by esrB and iron, and plays essential roles in the invasion of fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;27:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarez G, et al. Molecular characterization of a functional type VI secretion system from a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb Pathog. 2008;44:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez G, et al. A type VI secretion system effector protein, VgrG1, from Aeromonas hydrophila that induces host cell toxicity by ADP ribosylation of actin. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:155–168. doi: 10.1128/JB.01260-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerrant RL, Steiner TS, Lima AA, Bobak DA. How intestinal bacteria cause disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 2):S331–S337. doi: 10.1086/513845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennis G, Jr, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsushita K, et al. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaljo B, et al. Tristetraprolin is required for full anti-inflammatory response of murine macrophages to IL-10. J Immunol. 2009;183:1197–1206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitmore MM, et al. Negative regulation of TLR-signaling pathways by activating transcription factor-3. J Immunol. 2007;179:3622–3630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander WS, et al. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS): Negative regulators of signal transduction. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:588–592. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flo TH, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Handley SA, Miller VL. General and specific host responses to bacterial infection in Peyer’s patches: A role for stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3) during Salmonella enterica infection. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:94–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishikawa T, Rompikuntal PK, Lindmark B, Milton DL, Wai SN. Quorum sensing regulation of the two hcp alleles in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu J, et al. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3129–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052694299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva TM, et al. New evidence for an inflammatory component in diarrhea caused by selected new, live attenuated cholera vaccines and by El Tor and Q139 Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2362–2364. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2362-2364.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owen RL, Pierce NF, Apple RT, Cray WC., Jr M cell transport of Vibrio cholerae from the intestinal lumen into Peyer’s patches: A mechanism for antigen sampling and for microbial transepithelial migration. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1108–1118. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nazli A, et al. Enterocyte cytoskeleton changes are crucial for enhanced translocation of nonpathogenic Escherichia coli across metabolically stressed gut epithelia. Infect Immun. 2006;74:192–201. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.192-201.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stecher B, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:2177–2189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stecher B, Hardt WD. The role of microbiota in infectious disease. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rui H, Ritchie JM, Bronson RT, Mekalanos JJ, Zhang Y, Waldor MK. Reactogenicity of live-attenuated Vibrio cholerae vaccines is dependent on flagellins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915164107. (this issues) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fullner KJ, Mekalanos JJ. Genetic characterization of a new type IV-A pilus gene cluster found in both classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1393–1404. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1393-1404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skorupski K, Taylor RK. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene. 1996;169:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.