Abstract

Nanoparticles are actively exploited as biological imaging probes. Of particular interest are gold nanoparticles because of their nonblinking and nonbleaching absorption and scattering properties that arise from the excitation of surface plasmons. Nanoparticles with anisotropic shapes furthermore provide information about the probe orientation and its environment. Here we show how the orientation of single gold nanorods (25 × 73 nm) can be determined from both the transverse and longitudinal surface plasmon resonance by using polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging. By measuring the orientation of the same nanorods separately using scanning electron microscopy, we verified the high accuracy of this plasmon-absorption-based technique. However, care had to be taken when exciting the transverse plasmon absorption using a large numerical aperture objective as out-of-plane plasmon oscillations were also excited then. For the size regime studied here, being able to establish the nanorod orientation from the transverse mode is unique to photothermal imaging and almost impossible with conventional dark-field scattering spectroscopy. This is important because the transverse surface plasmon resonance is mostly insensitive to the medium refractive index and nanorod aspect ratio allowing nanorods of any length to be used as orientation sensors without changing the laser frequency.

Keywords: gold nanorod, surface plasmon, single-particle spectroscopy, photothermal imaging

Optical probes for biological imaging should yield large photon count rates with little background noise due to autofluorescence or scattering, have a high photostability and good biocompatibility, and cause only minimal interference (1–5). A high degree of polarization anisotropy is also desirable because it gives access to the orientation of the probe, and thereby provides important information about the conformation and dynamics of the biological system (1–3, 5). The surface plasmon (SP) absorption of individual metallic nanoparticles recorded by high-sensitivity photothermal imaging presents an excellent step toward the realization of optimized optical probes with the aforementioned properties (6, 7). Here we show that, by tuning the shape of gold nanoparticles and hence the anisotropy of the SP oscillation, the orientation of single gold nanorods (Au NRs) can be determined very accurately based on the SP absorption. We found excellent agreement for NR orientations determined using SEM compared to polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging of the longitudinal SP mode. Furthermore, our studies show that the transverse SP mode along the smaller NR dimension also yields accurate NR orientations if a low N.A. objective was used. This cannot be accomplished using conventional dark-field scattering spectroscopy (8, 9). In addition, because the transverse SP resonance is insensitive to the NR aspect ratio (10), the orientations of NRs with different lengths in environments with varying local refractive indices can be measured using only one laser frequency.

Single molecule fluorescence spectroscopy (1, 3, 11–17) has become an indispensible tool for determining the local orientation of synthetic and biological materials at the nanoscale because it avoids ensemble averaging of the measurable observables in heterogeneous systems. The orientation of the optical probe as well as the local order of the environment is obtained by measuring the fluorescence polarization anisotropy (1, 3, 11, 12, 14) or polarization-dependent absorption (2, 13, 17). Single molecule polarization-sensitive optical imaging has thus led to a wealth of new information on many complex processes in ordered systems. A few examples include the rotation mechanism of the F1-ATPase (17), the structural changes of myosin V (11, 18), the structure of Dendra-2-actin in fibroblast cells (12), the dynamics of polymers near the glass transition temperature (16), and the conformation and orientation of single polymer chains (13, 14). These studies employed fluorescent probes that include organic dye molecules (11, 12, 16, 17), fluorescent polymers (13, 14), and inorganic semiconductor nanoparticles (18). However, time-dependent fluorescence fluctuations (photoblinking) (19) and a limited measurement time before irreversible photochemical changes occur (photobleaching) (11, 16) present serious obstacles for imaging biological processes that span multiple time scales. Using semiconductor nanoparticles, photobleaching can be minimized and, for example, the lateral movement of CdSe nanoparticle coated glycine receptors has been measured for 20 min in living neurons (20). However, the potential toxicity of semiconductor nanoparticles remains a problem (21).

A different class of probes for biological applications is based on the SP resonance of plasmonic nanoparticles (22). The collective oscillation of the conduction band electrons in noble metal nanoparticles gives rise to very large scattering and absorption cross-sections (23). In addition to the high photostability (22), lack of photoblinking (24), and excellent biocompatibility (25), the polarization of the absorbed scattered light can be tuned readily through the shape of the nanoparticles allowing for orientational imaging (26). One of the best studied metallic nanoparticles with an anisotropic shape are Au NRs that have longitudinal and transverse SP modes polarized parallel to the long and short axes of the NRs, respectively (27). Several single-particle techniques such as dark-field imaging (28, 29), confocal microscopy (30), spatial modulation extinction spectroscopy (31, 32), and two photon luminescence (5) have been used to measure the polarization anisotropy of the longitudinal SP oscillation in single Au NRs. The most widely used technique among these methods is dark-field microscopy, which is based on SP scattering (8, 9, 28, 29, 33). However, scattering-based techniques are complicated by the fact that many other biological objects also scatter strongly giving rise to a large background and hence a decrease in sensitivity. In addition, the scattering cross-section scales with the nanoparticle radius R according to R6 (23). Metallic nanoparticles much smaller than about 50 nm in diameter are therefore not detectable by dark-field single-particle imaging (23). This prohibits a reduction in probe size although smaller particles are highly desirable in order to minimize any potential interference due to the probe itself.

A solution to this problem lies in the much weaker size dependence of the SP absorption cross-section that scales with R3 causing absorption to dominate for small nanoparticle sizes (23). Recently developed methods employing intensity or spatial modulation coupled with high sensitivity lock-in detection have indeed been able to visualize individual nanoparticles based on their absorption (6, 7, 24, 34–37) or total extinction (31, 32), respectively. In particular, absorption-based photothermal imaging, which detects the heat generated through fast nonradiative decay after photoexcitation (38), is capable of detecting metallic nanoparticles with diameters as small as 2 nm (34). It has been successfully used to track single membrane proteins labeled with 5–10 nm Au nanoparticles in cells (37). Photothermal imaging is furthermore insensitive to the presence of larger objects that predominantly scatter (39). However, accurately measuring the orientations of single Au NRs with polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging has not yet been shown. Here we demonstrate how the orientations of individual Au NRs can be determined based on the polarization anisotropy of both the transverse and longitudinal SP absorption. These studies present an important step toward the use of Au NRs as versatile plasmonic orientation sensors.

Results and Discussion

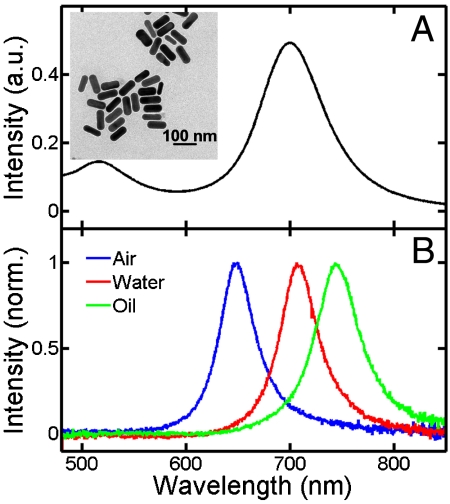

Polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging was performed on single Au NRs with a mean width of 25 nm and a mean length of 73 nm. As shown in Fig. 1A, the ensemble extinction spectrum of these Au NRs in aqueous solution had broad longitudinal and transverse SP bands, peaking at 700 and 514 nm, respectively. For this NR size, absorption dominates over scattering in the extinction spectrum, especially for the transverse SP (23). Therefore, a technique based on absorption is expected to be better suited in probing both longitudinal and transverse SP modes compared to dark-field scattering spectroscopy.

Fig. 1.

(A) Ensemble extinction spectrum of Au NRs taken in aqueous solution. (B) Single particle scattering spectra of the same Au NR deposited on glass and surrounded by different media. The inset shows a TEM image of the Au NRs having an average length and width of 73 and 25 nm.

For photothermal imaging of single Au NRs, the sample was deposited on a glass coverslip at low concentration to achieve a coverage of less than one NR per μm2. To excite the longitudinal and transverse SP absorptions, we used lasers with wavelengths of 675 and 514 nm as heating beams. Because of the strong dependence of the longitudinal SP resonance on the medium refractive index n (27), we first had to ensure that the 675-nm laser was able to efficiently excite the longitudinal SP. To address this issue, we measured the scattering spectra of the same single Au NR on a glass coverslip surrounded by air (n = 1), water (n = 1.3), and index-matched oil (n = 1.5), which is shown in Fig. 1B. The scattering spectra illustrate how the maximum of the longitudinal SP resonance redshifts with increasing medium refraction index. Although the relative cross-sections differ for SP absorption and scattering (40), the SP absorption maxima for these Au NRs coincide with the scattering maxima within a few nanometers (40). According to the scattering spectra, the longitudinal SP resonance was most efficiently excited with 675 nm when the Au NRs were covered with water. The water also allowed for better thermal conductivity between the Au NRs and the surrounding medium leading to an enhanced photothermal signal. Efficient excitation and heat transfer were important in order to avoid partial photothermal reshaping of the Au NRs. We independently confirmed the absence of any NR shape changes by measuring both scattering spectra and SEM images before and after the photothermal absorption experiments. Unless specifically stated otherwise, all photothermal measurements were carried out with Au NRs deposited on glass and surrounded by water.

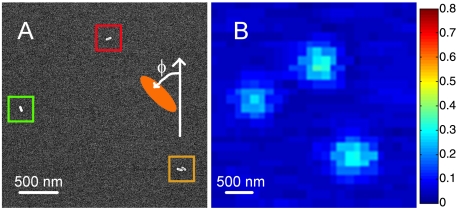

To correlate the orientations of individual NRs measured by SEM with those determined from polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging and to ensure that we were probing isolated NRs, we fabricated an identification pattern on the glass substrates using indexed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grids as masks and evaporating thin metal layers of 5 nm Ti followed by 20 nm Au. Fig. 2 shows SEM (A) and photothermal (B) images of the same two Au NRs and one NR dimer. This result demonstrates our ability to locate the same Au NRs with SEM and photothermal imaging. In Fig. 2B, the NR longitudinal SP resonance was excited by a circularly polarized 675 nm heating beam, which resulted in comparable photothermal intensities of all NRs regardless of the NR orientation.

Fig. 2.

SEM (A) and photothermal (B) images of the same area showing two single Au NRs and one NR dimer. The photothermal image was recorded with 675-nm excitation.

The vertical axis of the SEM image was selected as the reference for determining the orientation of Au NRs in the SEM images. We defined the orientation angle ϕ as the angle between the long axis of a NR and the reference axis. The orientation angle increased in the counterclockwise direction as shown in Fig. 2A. For the two Au NRs highlighted by the green and red squares in Fig. 2A, we obtained values of ϕ = 11° and 105° following this procedure.

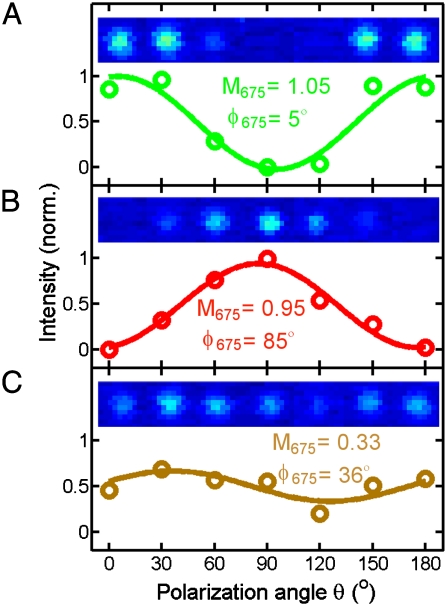

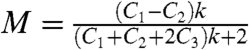

Polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging was carried out by linearly polarizing the 675 nm excitation beam and changing the polarization from 0° to 180° with respect to the reference axis in 30° increments. The photothermal intensities are plotted as a function of polarization angle in Fig. 3A and B for the same two Au NRs marked by the green and red squares in Fig. 2B. The insets show magnified photothermal images of the single Au NRs for the different polarization angles θ. It can clearly be seen from these photothermal polarization traces that the photothermal response of single Au NRs is highly polarized with a large contrast when excited at the longitudinal SP resonance. The observed polarization dependence of the photothermal intensity furthermore confirms that the longitudinal SP resonance behaves as a single dipole absorber and indicates that polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging can be used to determine the orientation of single NRs. For the two NRs in Fig. 2A, the photothermal polarization traces are 90° out of phase in agreement with their orthogonal orientation (ϕ = 11° and 105°).

Fig. 3.

Polarization dependence of the photothermal intensity for the NRs highlighted in Fig. 2. Note that the colors of the traces correspond to those of the boxes. The insets show the photothermal signal of the individual particles as a function of excitation polarization angle θ.

For a quantitative analysis of the NR orientations, we fitted the photothermal polarization traces to I(θ) = N(1 + M cos 2(θ - ϕ)). This equation has been successfully applied before to extract the orientation and conformation of single conjugated polymer chains, which, due to a limited exciton delocalization, are composed of multiple single dipole chromophores (13). The modulation depth M represents the average anisotropy of the absorption dipoles projected onto the sample plane. M = 1 if only a single dipole is present or all chromophores are aligned in a linear chain. On the other hand, M = 0 corresponds to a conformation in which all dipole projections are evenly distributed in the sample plane. Here, ϕ represents the angle of the longest projected dipole axis with respect to a reference frame, thereby giving the in-plane orientation of the major absorption dipole moment. We applied this formulism to the SP absorption of Au NRs because the transverse mode can be regarded as two orthogonally polarized oscillations, which furthermore overlap with unpolarized interband transitions. Before we elaborate more on the transverse SP mode, we first present a quantitative analysis of the longitudinal SP absorption.

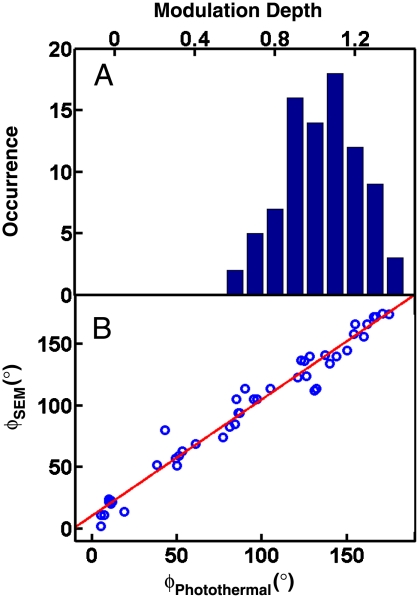

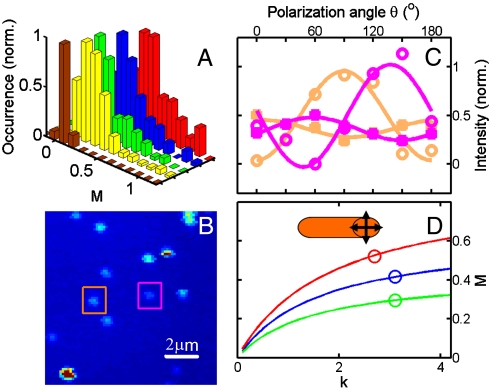

Our analysis confirms that, for single Au NRs deposited on a glass substrate, the longitudinal SP mode behaves like a single dipole absorber and that the direction of the SP oscillation is oriented parallel to the long NR axis. This result is in agreement with previous single NR scattering (9) and extinction measurements (32). The solid lines in Fig. 3 are fits of the measured polarization traces giving modulation depths of M675 = 1.05 and 0.95 for the NRs shown in Fig. 3A and B, respectively. To back up our conclusions with a statistically meaningful dataset, we measured the modulation depths for ∼200 single NRs with 675-nm excitation. Fig. 4A displays the histogram of measured modulation depths for the longitudinal SP absorption. The distribution has a maximum for M = 1 in agreement with a single dipole behavior of the longitudinal SP absorption. Interestingly, the modulation depth of a NR dimer is much smaller than one and the fit in Fig. 3C gives M675 = 0.33. A hybridization of the longitudinal and transverse SP modes in side-by-side NR dimers with similar interparticle separations has recently been observed by single-particle dark-field scattering spectroscopy (41) and is a likely explanation for the reduced modulation depth observed here for the SP absorption.

Fig. 4.

(A) Histogram of modulation depths for Au NRs excited at 675 nm. (B) NR orientations obtained from the modulation depth analysis are in very good agreement with the angles measured from the correlated SEM images. The red line is a linear regression.

The orientation angles obtained from the photothermal imaging agree well with those measured by SEM. The fits in Fig. 3A and B yield orientation angles of ϕ = 5° and 85° compared to the SEM values of 11° and 105°. The systematic deviation between these two techniques can be explained by the error introduced when overlaying corresponding photothermal and SEM images to determine the reference axis. Minor depolarization of the excitation light after passing through the high N.A. objective could have also contributed. Fig. 4B shows the correlation of orientation angles for 50 Au NRs determined independently by photothermal imaging and SEM. The solid line is a linear regression yielding ϕSEM = 0.95 ∗ ϕPhotothermal + 10.5° with r2 = 0.97. The excellent correlation between the orientation angles obtained by the two techniques validates that the orientation of single Au NRs can be accurately determined by polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging of the longitudinal SP even with a high-N.A. objective. Note that the intercept of the linear fit is 10.5°, which is consistent with the systematic deviation discussed already. Determining the orientation of single Au NRs by optical means is very important for live cell imaging when electron microscopy cannot be used. Because of a modulation depth of unity, it is furthermore possible to determine the orientation angle from the measurement of only two orthogonally polarized intensities I∥ and I⊥ by defining the polarization anisotropy  , in analogy to single molecule fluorescence polarization spectroscopy (14) (SI Text). This approach is significantly easier and faster because only two images have to be measured.

, in analogy to single molecule fluorescence polarization spectroscopy (14) (SI Text). This approach is significantly easier and faster because only two images have to be measured.

With M = 1, we measured one of the two extreme values of the modulation depth by polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging. Next, we also tested if the other extreme value, i.e., M = 0, can be detected for a single nanoparticle with randomly orientated dipole absorptions. We therefore acquired polarized photothermal images for 30-nm spherical Au nanoparticles embedded in a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) film with 514-nm excitation. The almost isotropic shape of a Au nanosphere results in a polarization-independent SP excitation. The photothermal traces were nearly independent of the polarization angle leading to a very small modulation depth close to zero. The distribution of modulation depths shown in Fig. 5A peaks at about zero with a mean value of 〈M514〉 = 0.07 ± 0.04 for 30 Au nanospheres of 30 nm, confirming that polarization-sensitive photothermal imaging is capable of measuring modulation depths over the entire range from zero to one. Small deviations from M = 0 are due to both an error in the fit as well as a slight anisotropy in the nanoparticle shape.

Fig. 5.

Photothermal imaging of nanospheres and NRs with 514-nm excitation. (A) Comparison of modulation depth histograms for 30-nm nanospheres in PVA film (Brown: n = 1.5, 〈M514〉 = 0.07 ± 0.04), 86-nm-long NRs in water (Yellow: n = 1.3, 〈M514〉 = 0.29 ± 0.20), 73-nm-long NRs in water (Green: n = 1.3, 〈M514〉 = 0.29 ± 0.21), and 73-nm-long NRs in oil (Blue: n = 1.5, 〈M514〉 = 0.42 ± 0.22). Included is also the distribution measured for 73-nm-long NRs in oil using an N.A. = 0.7 objective (Red: n = 1.5, 〈M514〉 = 0.52 ± 0.25). (B) Photothermal image of 73-nm-long Au NRs recorded with circularly polarized excitation at 514 nm. (C) Polarization dependence of the photothermal signal for the NRs highlighted by the colored squares in (B). The closed (open) circles correspond to excitation of the transverse (longitudinal) SP absorption. (D) Simulated modulation depth as a function of the ratio k between transverse SP and interband absorptions for objectives with N.A. = 1.3 and water as the surrounding medium (Green), N.A. = 1.3 and oil (Blue), and N.A. = 0.7 and oil (Red). The open circles indicate the experimentally determined mean modulation depths.

Determining the orientation of Au NRs also from the transverse mode is significant because, unlike the longitudinal SP resonance, the transverse SP resonance can be excited with the same laser frequency independent of the NR aspect ratio and refractive index of the surrounding environment. We therefore performed polarization-dependent photothermal imaging with 514-nm excitation. The modulation depth of the transverse SP absorption is expected to be nonzero but also smaller than one for Au NRs because of the polarization-independent interband transitions that overlap energetically with the transverse mode. Using spatial modulation spectroscopy, a polarization contrast ratio of 1.1 has been measured for the transverse SP resonance from the extinction spectrum of single Au NR with a diameter of ∼20 nm (32). As expected from ensemble measurements (26), they also found that the maximum of transverse SP extinction occurs at a polarization angle that is perpendicular to the longitudinal resonance. However, such a small polarization dependence suggests that it is difficult to extract the NR orientations from the transverse SP resonance. For NR diameters of ∼20 nm or smaller, dark-field spectroscopy is not sensitive enough to record the scattering of the transverse SP resonance (Fig. 1B). The high sensitivity of photothermal imaging to visualize single metal nanoparticles smaller than 10 nm in diameter (6, 24, 34) and the ability to determine the entire range of modulation depths therefore makes this technique ideally suited to test the polarization dependence of the transverse SP absorption.

Fig. 5B shows a photothermal image of Au NRs on glass and covered with water excited at 514 nm, which coincides with the peak of the transverse SP mode (Fig. 1A). The high signal-to-noise ratio exceeding 500 confirms that photothermal imaging can probe the transverse SP absorption of these Au NRs with a high sensitivity. The photothermal polarization traces for the two NRs marked by the colored squares in Fig. 5B are shown in Fig. 5C for both 514-nm (closed symbols) and 675-nm (open symbols) excitation. The traces are 90° out of phase in agreement with orthogonal polarizations of the two SP modes. The modulation depth for the transverse SP absorption is much smaller with M514 = 0.24 and 0.32 compared to M675 = 0.92 and 1.06 for the NRs highlighted by the orange and magenta squares, respectively. We obtained a mean modulation depth of 〈M514〉 = 0.29 ± 0.21 from 111 NRs (Fig. 5A). In addition, it is important to note that for these conditions we had problems fitting some photothermal polarization traces accurately to obtain M and especially ϕ because of the small polarization dependence of the transverse SP resonance. This makes it difficult to determine the NR orientations with 514-nm excitation when using a high-N.A. objective.

In order to exclude that a spectral overlap from the tail of the much more intense and orthogonally polarized longitudinal SP absorption did not lead to a depolarization and hence smaller measured modulation depth for the transverse SP mode, we also measured polarization-dependent photothermal images of longer Au NRs (25 × 86 nm) with 514-nm excitation. According to the ensemble extinction spectra in aqueous solution, the transverse SP maxima were at 514 nm for both 25 × 73 nm and 25 × 86 nm NRs, whereas the longitudinal SP maximum was redshifted from 700 to 750 nm for the longer NRs. However, we found that the modulation depths of both NR samples for 514-nm excitation and with water as the partially surrounding medium were nearly identical. The mean modulation depth for the 25 × 86 nm NRs was 〈M514〉 = 0.29 ± 0.20 and the distribution is also given in Fig. 5A. It can be concluded from these results that a contribution from the tail of the longitudinal SP resonance can be ignored for 514-nm excitation.

Finally, we also examined the effect of a high-N.A. objective. It is well known that the polarization at the focus of a high-N.A. objective has changed from that of the incident beam by acquiring polarization components that are perpendicular to the image plane and the original polarization direction (42). In fact, this depolarization can be used to determine the 3D orientation of single chromophores because transition dipoles aligned perpendicular to the sample surface can also be excited (18). The transverse SP of the cylindrically shaped Au NRs can be approximated as two dipole oscillations polarized perpendicular to each other, i.e., SP oscillations parallel and perpendicular to the sample plane as shown in the inset of Fig. 5D. Using a 514-nm heating beam and a high-N.A. objective, both these oscillations were excited in our experiments. However, the dipole absorption perpendicular to the sample plane surface is independent of the excitation polarization resulting in a smaller modulation depth. In addition to the N.A., the cone of excitation light and hence the out-of-plane polarization components are also determined by the refraction of the laser light at the interface between the glass substrate (n = 1.5) and the medium covering the NRs. For example, the smaller refractive index of water (n = 1.3) compared to index-matched oil (n = 1.5) causes a larger illumination cone. We indeed found that the out-of-plane polarization component was responsible for the low modulation depth of the transverse SP absorption and that it was possible to increase the modulation depth by changing to a low-N.A. objective and a higher refractive index of the medium covering the NRs. As shown in Fig. 5A, the modulation depths of the same Au NRs increased from 〈M514〉 = 0.29 ± 0.21 to 〈M514〉 = 0.42 ± 0.22 when water was replaced with oil. An additional increase to 〈M514〉 = 0.52 ± 0.25 was achieved by changing to an objective with N.A. = 0.7. It is worth noting that a redshift of the transverse SP absorption away from the interband transitions when changing from water to oil is expected to lead to a smaller modulation depth as the transverse SP resonance is peaked at 514 nm in water (Fig. 1A). We observed the opposite trend and therefore conclude that this effect can only play a minor role.

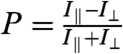

Because the depolarization caused by the optical elements can be calculated from the N.A. of the objective and the medium refractive index, we quantitatively modeled the modulation depths of the transverse SP absorption (Fig. 5D). Assuming that only unpolarized interband transitions and two perpendicular dipole oscillations of the transverse SP contribute to the NR absorption at 514 nm, we obtained the intrinsic degree of polarization of Au NRs at the excitation wavelength. Defining the ratio of transverse SP and interband absorptions as k, we can write the modulation depth as  , where C1, C2, C3 are the microscope correction factors (42). The derivation of this equation and how the correction factors are related to the N.A. of the objective is given in SI Text. Fig. 5D shows the simulated modulation depth as a function of k for the three different experimental conditions of objectives and surrounding media, i.e., N.A. = 1.3 and n = 1.3 (Green), N.A. = 1.3 and n = 1.5 in oil (Blue), and N.A. = 0.7 and n = 1.5 in oil (Red). Changing from oil to water as the surrounding medium for the low-N.A. objective causes only a very minor decrease in the modulation depth which is important for imaging biological samples. The open circles indicate the experimentally determined mean modulation depths from the histograms. The simulations then yield the corresponding k values of 3.1, 3.1, and 2.7, which are in excellent agreement for the different experimental conditions. We can therefore conclude that the transverse SP absorption is on average three times stronger than the interband absorption at 514 nm for this Au NR sample, where we assumed average modulation depths in these calculations. Despite the observed variation in modulations depths (which is discussed in SI Text), the general trend clearly shows that the choice of optical components is very important in these polarization-dependent single-particle studies.

, where C1, C2, C3 are the microscope correction factors (42). The derivation of this equation and how the correction factors are related to the N.A. of the objective is given in SI Text. Fig. 5D shows the simulated modulation depth as a function of k for the three different experimental conditions of objectives and surrounding media, i.e., N.A. = 1.3 and n = 1.3 (Green), N.A. = 1.3 and n = 1.5 in oil (Blue), and N.A. = 0.7 and n = 1.5 in oil (Red). Changing from oil to water as the surrounding medium for the low-N.A. objective causes only a very minor decrease in the modulation depth which is important for imaging biological samples. The open circles indicate the experimentally determined mean modulation depths from the histograms. The simulations then yield the corresponding k values of 3.1, 3.1, and 2.7, which are in excellent agreement for the different experimental conditions. We can therefore conclude that the transverse SP absorption is on average three times stronger than the interband absorption at 514 nm for this Au NR sample, where we assumed average modulation depths in these calculations. Despite the observed variation in modulations depths (which is discussed in SI Text), the general trend clearly shows that the choice of optical components is very important in these polarization-dependent single-particle studies.

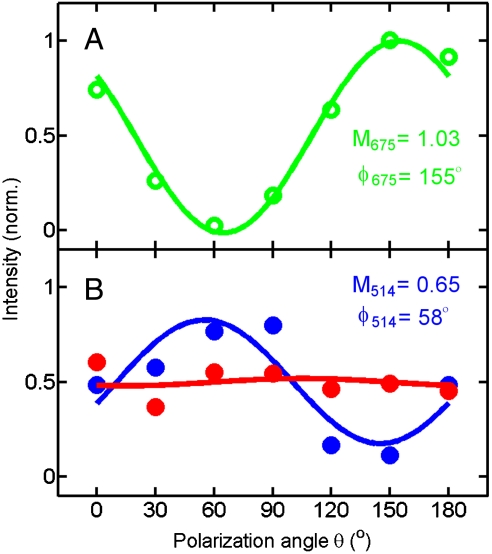

The effects of a high-N.A. objective and the refractive index mismatch with the surrounding medium on the modulation depth can be even better illustrated by comparing the photothermal polarization traces for the same NR using different excitation conditions. Fig. 6A shows the polarization trace of a Au NR for 675-nm excitation covered with water using an N.A. = 1.3 objective. Despite the large N.A., any excitation light that becomes polarized perpendicular to the long NR axis (parallel and perpendicular to the sample plane) will not be absorbed by the NR as the transverse SP mode absorbs at shorter wavelength than 675 nm. We therefore obtained a modulation of unity (M675 = 1.03) and the NR orientation of ϕ = 155° agrees well with the angle measured by SEM (ϕ = 160°). However, when the transverse SP resonance of the same Au NR covered with water is excited at 514 nm using the same high-N.A. objective, out-of-plane polarized light is absorbed by the transverse mode independent of the polarization angle yielding a small modulation depth of M514 = 0.04 (Fig. 6B, red symbols). A smaller N.A. and a refractive index-matched medium cause a smaller illumination cone and reduce the component of excitation light with a polarization vector perpendicular to the image plane. Therefore, measuring the photothermal polarization trace for the same NR covered with oil and using an N.A. = 0.7 objective, yields a much a higher modulation depth of M514 = 0.65 and better fit with an orientation angle of ϕ = 58° in very good agreement with the one measured using 675-nm excitation, considering the 90° phase shift for the two SP resonances. As discussed above, determining the NR orientation by exploiting the polarization dependence of the transverse SP resonance is important because the transverse mode is mostly insensitive to changes in the environment and the NR aspect ratio compared to the longitudinal mode. Thus, only a single excitation wavelength is necessary to probe the orientations of different NRs regardless of the NR size and medium refractive index, which is particularly important for a laser-based high-sensitivity detection method such as photothermal imaging.

Fig. 6.

Polarization dependence of the photothermal intensity for the same Au NR using different excitation wavelengths, numerical apertures, and media. (A) 675 nm, N.A. = 1.3, n = 1.3; (B) 514 nm, N.A. = 1.3, n = 1.3 (Red) and 514 nm, N.A. = 0.7, n = 1.5 (Blue).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the polarization-dependent photothermal imaging of Au NRs. The polarization dependence of the NRs has been exploited to develop a unique absorption-based single-particle method that allowed us to accurately determine the orientation of individual Au NRs by selectively exciting either of two SP resonances. In particular, our results show that, by exciting the transverse SP resonance when using a low-N.A. objective, the NR orientation can be accurately probed, which is difficult with conventional dark-field scattering spectroscopy and significant because of the invariance of the transverse SP absorption with respect to the NR aspect ratio. Correlated SEM imaging furthermore independently verified the Au NR orientations obtained from the polarization dependent photothermal images. The combination of a nonphotobleaching and nonphotoblinking Au NR vector probe with a high-sensitivity single-particle absorption method brings together many of the desired properties of an optical probe and hence promises to be highly effective for investigating the orientation and dynamics of macromolecules over extended time periods even in highly scattering environments, e.g., probing the local structure of liquid crystalline materials including synthetic and biological membranes or the anisotropic conformation and diffusion of proteins in living cells. In addition, the much larger sensitivity of photothermal imaging compared to dark-field scattering spectroscopy will make it possible to further reduce the size of the Au NR probe, especially as synthetic methods become available that can produce Au NRs with diameters < 5 nm, and to significantly increase the data acquisition speed. In particular, with the use of an electrooptic modulator it should be possible to follow the orientation of a single Au NR on the few millisecond time scale.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

Microscope cover glasses were cleaned by first sonicating in acetone for 15 min, and then in methanol for 15 min, followed by O2 plasma cleaning for 1 min. After cleaning the slides, a pattern was created by evaporating a 5-nm Ti layer followed by a 20-nm Au layer through an indexed copper TEM grid (Ted Pella, Inc.) placed on the cleaned glasses. This pattern aided in locating the same particles in SEM and optical microscopy. Gold nanospheres of 30-nm in diameter (part #10-A-100), 73-nm (part #30-25-700), and 86-nm (part #30-25-750) long Au NRs were obtained from Nanopartz. The colloidal solutions were diluted and sonicated for 3 min to prevent particle aggregation. A drop of the diluted solution was then casted onto the cleaned and patterned glass slides and allowed to dry. Water or objective immersion oil were added on top of the sample. Water evaporation was prevented by adding a thin mylar spacer and second cover glass. SEM characterization was carried out using a Quanta ESEM2 SEM (FEI) operated under low vacuum in a water vapor atmosphere at 30 kV.

Polarization-Sensitive Photothermal Imaging.

Photothermal imaging requires a combination of a time-modulated heating beam and a probe beam. In this study, a 514 nm Ar+ laser (Modu-Laser) was used as a heating beam for exciting the SP absorption of Au nanospheres and the transverse SP mode of Au NRs. A 675-nm diode laser (Power Technology) was used as a heating beam for the longitudinal SP absorption of Au NRs. The polarization of the heating beams was controlled using half and quarter waveplates. A 633-nm He-Ne laser (JSD Uniphase) was employed as a probe beam. The heating and probe beams were carefully overlaid each time after changing the polarization of the heating beam. Intensity modulation of the heating beam at 400 kHz was carried out with an acoustooptic modulator (IntraAction). The laser beams were directed into an inverted microscope (Zeiss) and focused on the sample with a Fluar (oil immersion, 100x, N.A. = 1.3) or a Plan-Apochromat (oil immersion, 63x, N.A. = 0.7) objective. The photothermal signal was detected by a 125 MHz photoreceiver (New Focus) and fed into a lock-in amplifier (Princeton Applied Research), which was connected to a surface probe microscope controller (RHK Technology). Photothermal images were acquired using a 2D piezoscanning stage (Physik Instrumente). Photothermal polarization traces of multiple Au NRs were constructed from a series of 20 × 20-μm2 images taken with different excitation polarizations using an automated particle finding routine developed in Matlab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Laurent Cognet for help with the photothermal imaging setup, Christian Schoen from Nanopartz for supplying the gold nanospheres and nanorods free of charge, and Jason Hafner for the use of his plasma cleaner. S.L. thanks The Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant C-1664) and 3M for a Nontenured Faculty Grant. W.S.C. acknowledges support from The Richard E. Smalley Institute for a Peter and Ruth Nicholas Fellowship, and L.S.S. was supported by an Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0910127107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chung IH, Shimizu KT, Bawendi MG. Room temperature measurements of the 3D orientation of single CdSe quantum dots using polarization microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:405–408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0133507100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartschuh A, Pedrosa HN, Novotny L, Krauss TD. Simultaneous fluorescence and Raman scattering from single carbon nanotubes. Science. 2003;301:1354–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1087118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, et al. Linearly polarized emission from colloidal semiconductor quantum rods. Science. 2001;292:2060–2063. doi: 10.1126/science.1060810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michalet X, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HF, et al. In vitro and in vivo two-photon luminescence imaging of single gold nanorods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15752–15756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504892102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer D, Tamarat P, Maali A, Lounis B, Orrit M. Photothermal imaging of nanometer-sized metal particles among scatterers. Science. 2002;297:1160–1163. doi: 10.1126/science.1073765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cognet L, et al. Single metallic nanoparticle imaging for protein detection in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11350–11355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu M, et al. Dark-field microscopy studies of single metal nanoparticles: Understanding the factors that influence the linewidth of the localized surface plasmon resonance. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:1949–1960. doi: 10.1039/b714759g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonnichsen C, et al. Drastic reduction of plasmon damping in gold nanorods. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:077402/1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.077402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Spectral properties and relaxation dynamics of surface plasmon electronic oscillations in gold and silver nanodots and nanorods. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8410–8426. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forkey JN, Quinlan ME, Alexander Shaw M, Corrie JET, Goldman YE. Three-dimensional structural dynamics of myosin V by single-molecule fluorescence polarization. Nature. 2003;422:399–404. doi: 10.1038/nature01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould TJ, et al. Nanoscale imaging of molecular positions and anisotropies. Nat Methods. 2008;5:1027–1030. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu DH, et al. Collapse of stiff conjugated polymers with chemical defects into ordered, cylindrical conformations. Nature. 2000;405:1030–1033. doi: 10.1038/35016520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Link S, Chang WS, Yethiraj A, Barbara PF. Orthogonal orientations for solvation of polymer molecules in smectic solvents. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:017801/1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.017801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sick B, Hecht B, Novotny L. Orientational imaging of single molecules by annular illumination. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;85:4482–4485. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartko AP, Xu K, Dickson RM. Three-dimensional single molecule rotational diffusion in glassy state polymer films. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:026101/1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.026101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishizaka T, et al. Chemomechanical coupling in F-1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:142–148. doi: 10.1038/nsmb721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toprak E, et al. Defocused orientation and position imaging (DOPI) of myosin V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6495–6499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507134103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moerner WE, Orrit M. Illuminating single molecules in condensed matter. Science. 1999;283:1670–1676. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahan M, et al. Diffusion dynamics of glycine receptors revealed by single-quantum dot tracking. Science. 2003;302:442–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1088525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derfus AM, Chan WCW, Bhatia SN. Probing the cytotoxicity of semiconductor quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2004;4:11–18. doi: 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sperling RA, Rivera Gil P, Zhang F, Zanella M, Parak WJ. Biological applications of gold nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1896–1908. doi: 10.1039/b712170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dijk MA, et al. Absorption and scattering microscopy of single metal nanoparticles. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:3486–3495. doi: 10.1039/b606090k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berciaud S, Lasne D, Blab GA, Cognet L, Lounis B. Photothermal heterodyne imaging of individual metallic nanoparticles: Theory versus experiment. Phys Rev B. 2006;73:045424/1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy CJ, et al. Gold nanoparticles in biology: Beyond toxicity to cellular imaging. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1721–1730. doi: 10.1021/ar800035u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Zande BMI, Koper GJM, Lekkerkerker HNW. Alignment of rod-shaped gold particles by electric fields. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:5754–5760. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KS, El-Sayad MA. Dependence of the enhanced optical scattering efficiency relative to that of absorption for gold metal nanorods on aspect ratio, size, end-cap shape, and medium refractive index. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:20331–20338. doi: 10.1021/jp054385p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubert O, et al. Mapping the polarization pattern of plasmon modes reveals nanoparticle symmetry. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2345–2350. doi: 10.1021/nl801179a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonnichsen C, Alivisatos AP. Gold nanorods as novel nonbleaching plasmon-based orientation sensors for polarized single-particle microscopy. Nano Lett. 2005;5:301–304. doi: 10.1021/nl048089k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Failla AV, Qian H, Qian H, Hartschuh A, Meixner AJ. Orientational imaging of subwavelength au particles with higher order laser modes. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1374–1378. doi: 10.1021/nl0603404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arbouet A, et al. Direct measurement of the single-metal-cluster optical absorption. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:127401/1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.127401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muskens OL, et al. Quantitative absorption spectroscopy of a single gold nanorod. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:8917–8921. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherry LJ, et al. localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy of single silver nanocubes. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2034–2038. doi: 10.1021/nl0515753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berciaud S, Cognet L, Blab GA, Lounis B. Photothermal heterodyne imaging of individual nonfluorescent nanoclusters and nanocrystals. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:257402/1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.257402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulzer F, et al. Photothermal detection of individual gold nanoparticles: Perspectives for high-throughput screening. Chemphyschem. 2008;9:1761–1766. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Octeau V, et al. Photothermal absorption correlation spectroscopy. ACS Nano. 2009;3:345–350. doi: 10.1021/nn800771m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasne D, et al. Single nanoparticle photothermal tracking (SNaPT) of 5-nm gold beads in live cells. Biophys J. 2006;91:4598–4604. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Link S, Hathcock DJ, Nikoobakht B, El-Sayed MA. Medium effect on the electron cooling dynamics in gold nanorods and truncated tetrahedra. Adv Mater. 2003;15:393–396. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Born M, Wolf E. Principles of Optics. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain PK, Lee KS, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Calculated absorption and scattering properties of gold nanoparticles of different size, shape, and composition: Applications in biological imaging and biomedicine. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:7238–7248. doi: 10.1021/jp057170o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Funston AM, Novo C, Davis TJ, Mulvaney P. Plasmon coupling of gold nanorods at short distances and in different geometries. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1651–1658. doi: 10.1021/nl900034v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forkey JN, Quinlan ME, Goldman YE. Protein structural dynamics by single-molecule fluorescence polarization. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.