Abstract

We describe an antiviral small molecule, LJ001, effective against numerous enveloped viruses including Influenza A, filoviruses, poxviruses, arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, paramyxoviruses, flaviviruses, and HIV-1. In sharp contrast, the compound had no effect on the infection of nonenveloped viruses. In vitro and in vivo assays showed no overt toxicity. LJ001 specifically intercalated into viral membranes, irreversibly inactivated virions while leaving functionally intact envelope proteins, and inhibited viral entry at a step after virus binding but before virus–cell fusion. LJ001 pretreatment also prevented virus-induced mortality from Ebola and Rift Valley fever viruses. Structure–activity relationship analyses of LJ001, a rhodanine derivative, implicated both the polar and nonpolar ends of LJ001 in its antiviral activity. LJ001 specifically inhibited virus–cell but not cell–cell fusion, and further studies with lipid biosynthesis inhibitors indicated that LJ001 exploits the therapeutic window that exists between static viral membranes and biogenic cellular membranes with reparative capacity. In sum, our data reveal a class of broad-spectrum antivirals effective against enveloped viruses that target the viral lipid membrane and compromises its ability to mediate virus–cell fusion.

Keywords: virology, viral entry, fusion inhibitor, small molecule, lipid membrane

Few licensed and efficacious broad-spectrum antivirals exist. Examples include ribavirin, which functions via nebulous effects on both host and virus proteins, and α-IFN, which produces unwanted side effects and remains impractically expensive for widespread use (1 –5). The rapid rise in the number of emerging viral pathogens brings into stark contrast our limited resources to develop therapeutics on a single-pathogen basis (6) and underscores the need to develop broad-spectrum antivirals that target common components of large classes of viruses.

Viruses can be divided generally into two main categories: lipid-enveloped or nonenveloped (naked). Enveloped viruses replicate within the host cell, recruit their own proteins to the host membrane, then bud from and use that membrane, essentially, as a vehicle to transport the viral genome into the next target host cell. Although the viral lipid membrane derives from the host cell, it differs from cellular membranes in several biochemical and biophysical properties such as biogenic reparative capacity (7 –9).

Because the introduction of certain molecules, such as lysophosphotidylcholine, can stabilize positive spontaneous curvature of membranes and prevent entry of several viruses that fuse via different mechanisms, such as influenza, HIV-1 (class I fusion), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (class II fusion) (7, 9 –13), it stands to reason that introduction of small molecules that insert, intercalate, or otherwise bind to the proximal monolayer may disturb the membrane dynamics required for successful virus–cell fusion, thereby preventing virus entry into target cells (7, 10, 14, 15). Also, amphipathic peptides derived from the NS5A protein of hepatitis C virus (HCV) can disrupt viral membranes physically and have been reported to inhibit a variety of enveloped viruses (16, 17). These examples support the hypothesis that inhibitors that target and disrupt the lipid interfaces mediating virus–cell fusion could be developed as broad-spectrum antivirals.

To survive, mammalian cells must be able to repair and replenish their lipid bilayers efficiently. Mammalian cells possess a “biogenic” membrane, actively able to replace and synthesize lipids, that viruses lack (18). Through poorly understood mechanisms, the mammalian cell can respond to large (10 μm) or small (<0.2 μm) plasma membrane lesions via several rapid (within seconds) repair processes requiring lesion detection, exocytosis of endosomal organelles, and/or self-sealing lipid repair (19 –21). Virions inherently lack the ability to produce/recycle lipids actively and, unlike their host cells, cannot repair damage to or deformation of their membrane (19 –21). Additionally, host cells constantly metabolize and recycle fatty acids and other membrane components to replenish and repair their plasma membranes (8, 22 –25). Viral membranes, although derived from the host cells, lack these metabolic and repair pathways, leaving their membranes susceptible to specific disruption. Thus, the host-derived viral membrane represents a discrete and susceptible target for antiviral inhibitors. Here, we report on a broad-spectrum antiviral inhibitor that targets the viral lipid membrane, exploiting its lack of biogenic reparative capacity to effectuate the compound’s antiviral efficacy.

Results

Discovery of a Broad-Spectrum Antiviral.

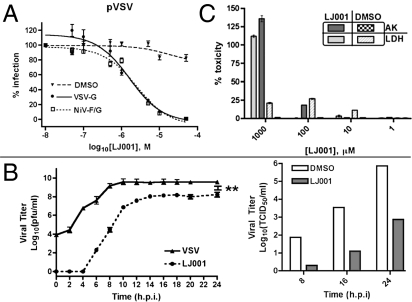

During a high-throughput screen to find inhibitors of Nipah virus (NiV) entry, we identified an aryl methyldiene rhodanine derivative, termed “LJ001,” that inhibited the entry of pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-luciferase reporter virus (VSV∆G::Renilla luciferase) in an envelope-independent manner (Fig. 1A). This finding was confirmed by LJ001’s ability to inhibit infection and infectious spread of live NiV and VSV in vitro (Fig. 1B). Because these two viruses belong to the order Mononegavirales, we questioned whether LJ001 targets gene expression mechanisms common to nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses. In vitro assays, however, indicated that VSV mRNA transcription and capping remain unaffected in the presence of 10 μM LJ001 (Fig. S1). Cytoplasmic enzyme release assays indicated that LJ001 was not toxic at effective antiviral concentrations (10 μM ≥ IC90 for most viruses) (Fig. 1C). In addition, Vero cells could be passaged repeatedly in 10 μM LJ001 over a period of 4 days with no overt deficiencies in cell division and gross morphology (Fig. S2A); and Alamar Blue uptake assays (27) indicated no effect on active cell metabolism in LJ001-treated Vero cells (Fig. S2B). Finally, LJ001 also exhibited no gross toxicity in vivo (Fig. S2C). Complete blood chemistry panels, blood cell counts, and organ toxicology tests conducted in mice dosed by oral gavage or i.p. with 20 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg of LJ001 revealed no abnormalities except a slight elevation in serum cholesterol levels in the treated vs. vehicle control group (Fig. S2D).

Fig. 1.

Discovery of a broad-spectrum antiviral. (A) Pseudotyped VSV (pVSV) with the indicated envelope was pretreated with LJ001 or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle) for 10 min at 25 °C and then was used to infect Vero cells for 1 h at 37 °C (± SEM; normalized DMSO at 100%). (B) VSV-Indiana (Left) at an MOI of 3 was treated as in A, and infection was quantified by a standard plaque assay from supernatant samples (±SEM). **, P < 0.001 (>96% inhibition). NiV (Right) at an MOI of 3 was treated as in A with 10 μM LJ001, and measurements of the 50% tissue-culture infective dose were taken at the indicated time points. For both viruses in B, the infectious inoculum was replaced with growth media containing LJ001 at the indicated concentrations after the infection period indicated. (C) Vero cells were treated with varying concentrations of LJ001 for 1 h at 37 °C and assayed for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and adenylate kinase (AK) release (±SD). h.p.i., hours postinfection

LJ001 Inhibits Enveloped but Not Nonenveloped Viruses.

Next, we investigated the breadth of LJ001’s broad-spectrum antiviral capability. Remarkably, LJ001 inhibited entry, or infectious spread, of a wide variety of lipid-enveloped viruses including Influenza A, HIV (Fig. S3B), HCV (Fig. S3G), and a large number of highly virulent category A–C priority pathogens, including Ebola (Fig. S3A) and Junín (Fig. S3D) hemorrhagic fever viruses, without affecting nonenveloped viruses (Table 1 and Fig. S3). Despite different target cell types, viruses, and assay readouts measuring infectivity, LJ001 demonstrated roughly similar efficacy among the enveloped viruses tested. These results suggest a common mechanism of LJ001-mediated inhibition: The compound probably targets an invariant component among all enveloped viruses.

Table 1.

LJ001 inhibits a variety of enveloped but not nonenveloped viruses in vitro

| Virus | Family | Genome type | Envelope (yes/no) | Activity |

| EbolaL (cat A) | Filoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| MarburgL (cat A) | Filoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| Influenza AL (cat A) | Orthomyxoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | +++ |

| JunínL (cat A) | Arenaviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| Rift Valley feverL (cat A) | Bunyaviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | +++ |

| LaCrosseL (cat B) | Bunyaviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | +++ |

| NipahL,P (cat C) | Paramyxoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| Omsk hemorrhagic feverL (cat C) | Flaviviridae | ssRNA(+) | Y | ++ |

| RSSEL (cat C) | Flaviviridae | ssRNA(+) | Y | ++ |

| PIV-5L | Paramyxoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| HPIV-3L | Paramyxoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| Newcastle diseaseL* | Paramyxoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| HIV-1L,P* | Retroviridae | ssRNA(−)RT | Y | ++ |

| Murine leukemiaL | Retroviridae | ssRNA(−)RT | Y | ++ |

| Yellow feverL | Flaviviridae | ssRNA(+) | Y | +++ |

| Hepatitis CL | Flaviviridae | ssRNA(+) | Y | +++ |

| West NileL | Flaviviridae | ssRNA(+) | Y | +++ |

| Vesicular stomatitisL,P | Rhabdoviridae | ssRNA(−) | Y | ++ |

| CowpoxL | Poxviridae | dsDNA | Y | + |

| VacciniaL | Poxviridae | dsDNA | Y | ++ |

| AdenovirusL** | Adenoviridae | dsDNA | N | − |

| Coxsackie BL** | Picornaviridae | ssRNA(+) | N | − |

| ReovirusL | Reoviridae | dsRNA | N | − |

Virus infection was performed at various concentrations of LJ001, and inhibition was determined by measuring resultant viral titers by standard plaque assays or the 50% tissue-culture infective dose, unless indicated otherwise. Raw data for representative viruses are shown in Fig. S3.

*qPCR;

**flow cytometric analysis of recombinant GFP expressing virus;

+1 μM < IC50 < 5 μM;

++0.5 μM < IC50 ≤ 1μM;

+++IC50 < 0.5 μM;

-no significant inhibition at >10μM;

Ppseudotyped viruses were tested;

Llive viruses were tested.

LJ001 Inactivates Virions and Prohibits Viral Entry.

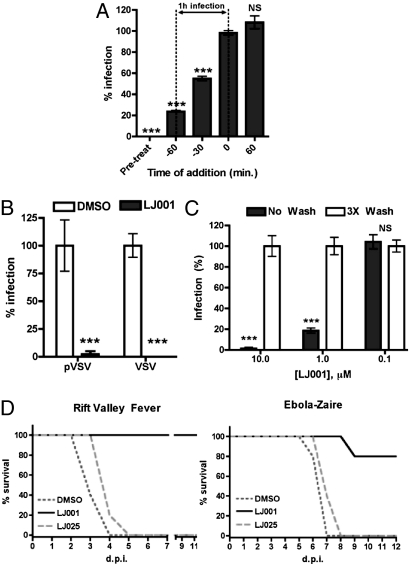

To characterize LJ001’s mechanism of inhibition, we first sought to determine if LJ001 acts on the virus or on the host cell. Time-of-addition experiments (Fig. 2A) indicated that LJ001’s inhibitory effect was apparent only when added before or during, but not after, the virus infection period, suggesting that LJ001 acts on the virus during the entry process. To demonstrate further that LJ001 acts on the virus, we pretreated live VSV and NiV-envelope pseudotyped VSV (NiV-pVSV) with LJ001, washed and repurified the virions from excess compound, and tested the infectivity of the repurified viruses (Fig. 2B). Viruses treated in this manner were noninfectious. Similar results were obtained for live human parainfluenza virus-3. The inactivation appeared to be irreversible, because rewashing the virus in an excess of PBS for 4 hours followed by a secondary repurification step resulted in viruses that remained noninfectious. Furthermore, to show that LJ001 does not act on the cells, we pretreated target cells with 10 μM of LJ001 for the indicated times, washed them rigorously to remove residual compound, and then infected the cells with pVSV (Fig. 2C). Washing the cells reversed the inhibitory effect of LJ001. Finally, to show that viral inactivation was not an artifact of in vitro infection assays, we challenged groups of mice with lethal doses of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) or mouse-adapted Ebola-Zaire virus (maZEBOV) pretreated (ex vivo) with LJ001, LJ025, or vehicle control (Fig. 2D). LJ025 is an inactive derivative that differs from LJ001 by an atomic sulfur to oxygen change in the active pharmacophore (see structure–activity relationship analysis below). RVFV and Ebola virus are highly pathogenic viruses classified as National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease category A priority pathogens. Only LJ001-pretreated RVFV or maZEBOV prevented mortality in 100% and 80% of animals, respectively. In sum, our data show that LJ001 acts specifically on the virus and not on the cell.

Fig. 2.

LJ001 inactivates virions and prohibits viral entry. (A) pVSV was used to infect Vero cells as previously described. LJ001 (10 μM) was added at the indicated time relative to the infection end point (±SD). (B) Viruses were treated with 10 μM LJ001 for 10 min at 25 °C and then were washed with PBS, followed by repurification by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion. Repurified viruses were used to infect cells as previously described (±SD). (C) Vero cells were treated with 1 μM or 10 μM compound for 10, 30, or 120 min at 37 °C in PBS (+10% FBS) and either left alone (No Wash) or washed three times (3 × Wash), followed by infection with pVSV (individual data sets normalized to corresponding vehicle control or negative compound, ±SD). (D) Equivalents of 100 × LD50 of RVFV-ZH501 or maZEBOV were treated ex vivo with 20 μM LJ001, 20 μM LJ025, or 2.5% DMSO for 20 min at 25 °C and then were used to infect mice (RVFV, n = 5; maZEBOV, n = 5) via i.p. injection. ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

LJ001 Binds, Perturbs, and Irreversibly Targets the Viral Membrane.

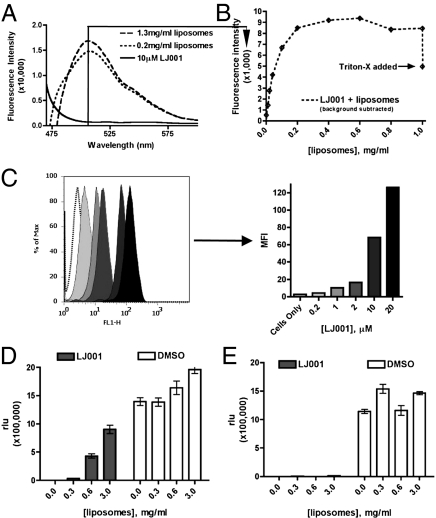

Because LJ001 acts on the virus and not on the cells, we hypothesized that LJ001 probably targets a viral component common to all enveloped viruses: the viral lipid membrane which, although derived from the host-cell membrane, also differs in many biophysical and physiological properties. Thus, we tested the ability of LJ001 to bind enveloped viruses or manufactured liposomes. LJ001 has inherent fluorescent properties that allowed us to use a fluorescence intensity-based membrane intercalation assay to analyze LJ001’s ability to bind liposomes physically. Fig. 3 A and B shows that although LJ001 has minimal fluorescence in aqueous solvent alone, it fluoresces strongly in the presence of increasing concentrations of liposomes. LJ001’s ability to intercalate into lipid membranes is saturable and dependent on the intact liposomal membrane, because introduction of detergent results in a loss of fluorescence (Fig. 3B). As would be expected, LJ001 also binds to cellular membranes (Fig. 3C). Yet, LJ001 clearly acts on the virus and not on the cells (Fig. 2), perhaps underscoring underlying physiological differences between virus and cellular membranes.

Fig. 3.

LJ001 binds, perturbs, and irreversibly targets the viral membrane. (A) Liposomes were titered into solution containing 10 μM LJ001 (excitation: 450 nm, emission: 510 nm), and fluorescence was monitored at the indicated wavelengths using a PTI QM4 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer). Representative raw data are shown. The solid line indicates no liposomes; dashed and dotted lines indicate increasing liposomal titrations. (B) A quantification of individual peaks at 510 nm as increasing concentrations of liposomes were titered into solution. Triton-X (0.1% final concentration) was added at the end of the assay to show that the increasing fluorescence depended on intact liposomes. These data were corrected for the scattering caused by the addition of liposomes by repeating the experiments in the absence of LJ001 and subtracting the liposome-induced scattering signal (±SEM). (C) (Left) Twenty-five thousand Vero cells were stained with increasing concentrations of LJ001 for 30 min at 37 °C in normal growth media and then were harvested by trypsinization and analyzed for mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) by flow cytometry. (Right) Bar graph shows MFI values. (D) Vero cells were infected with pVSV as previously described while simultaneously being subjected to 10 μM LJ001 and liposomes (±SD). (E) Vero cells were infected with pVSV as previously described. In this case, pVSV was treated with 10 μM LJ001 for 10 min at 25 °C and then subjected to varying concentrations of liposomes (±SD).

Given that LJ001 binds to lipid membranes, we sought to determine if its inhibitory effect during infection can be reversed by the addition of liposomes. Again, we infected cells with NiV-pVSV in the presence of increasing liposome concentrations while keeping the concentration of LJ001 constant (Fig. 3D). The liposomes reversed LJ001’s inhibitory effect; however, this assay was conducted by simultaneously subjecting both the virus and liposomes to LJ001. If the viral particles are pre-exposed to LJ001 before the mixture is added to liposomes, the presence of excess liposomes no longer can rescue viral infection (Fig. 3E). These data are consistent with our observations that LJ001 acts on virus membranes and does so in an irreversible manner (Fig. 2).

To assess if membrane curvature has any impact on LJ001’s antiviral activity, we performed liposome binding and infection-competition assays, such as those performed in Fig. 3 A and D, using liposomes ranging in size from 50 nm to 600 nm and observed no differential effect in LJ001 binding or reversal of inhibition (Fig. S4 A and B). This finding is consistent with the range of viruses inhibited, which differ in size, shape, and morphology.

Because LJ001 intercalates into the viral membrane, we sought to determine if the virus particles themselves become visually disrupted upon treatment. We imaged DMSO-, LJ001-, or LJ025-treated (an inactive analog with a single-atom S to O change; Table S1) pVSV particles via electron microscopy. Only LJ001 induced a significant distortion of the viral membrane (Fig. S5A), albeit at higher concentrations than those needed for viral neutralization. The obvious presence of the negative stain in the interior of virions treated with LJ001, but not in virions treated with LJ025 or DMSO, also suggests that the virion membrane has been permeabilized to some degree.

Medicinal Chemistry and Structure–Activity Relationship Analysis of LJ001.

Next, we conducted a structure–activity relationship analysis with 26 derivatives of LJ001 to analyze functional group requirements for efficacy. These molecules, all aryl methylene rhodanine derivatives, generally are polar on the left-hand side and nonpolar on the right-hand side, as drawn (Table S1). Small nonpolar substituents at the 2- and 3-position of the right-hand phenyl ring give good activity (LJ006-LJ012), whereas small polar substituents, e.g., OH, NH2, N2 (LJ016, LJ017, LJ020), generally afford lower activity. On the left-hand side, nonpolar (LJ001–LJ005) and polar (LJ021–022) groups can act as substituents on the ring nitrogen without loss in activity. One even can attach a biotin moiety and retain good activity (LJ024). In the middle, the best aryl group is a 5-substituted 2-furyl ring because substitution of a 2-thiophenyl (LJ018) or a 5-oxazolyl (LJ023) unit led to less active compounds, whereas the 3-substituted phenyl analogue (LJ019) was inactive. The aryl ring must have a large substituent at the 5-position because the methyl and hydrido analogs (LJ013-014) are inactive. Finally, substitution of the thioxo group with an oxo group at the left-hand polar end gave a completely inactive compound (LJ025) (Fig. S6A). The double bond of the aryl methylene unit also is crucial because the dihydro analog LJ033 is completely inactive (Table S1). Thus, the active antiviral pharmacophore on the left-hand polar end requires a thioxo group in the thiazolidine ring and a double bond between the two heterocyclic rings. The nonpolar right-hand end is necessary but not sufficient for its antiviral effect, because LJ025 also intercalates into membranes but is otherwise inactive (Fig. S6 A–C). Thus, the nonpolar right-hand side likely inserts into the hydrophobic lipid environment and positions the more polar thiazolidine unit for activity (which is much more tolerant of the size and polarity of the attached groups). Possible mechanisms of action based on this model are presented in Discussion.

LJ001-Treated Virions Remain Grossly Intact.

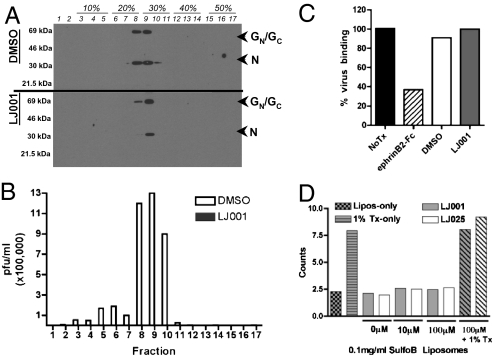

Physical disruption of viral particles has been proposed as the basis for the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of a peptide derived from the NS5A protein of HCV (16, 17). To determine if this disruption also was the mechanistic basis for LJ001’s action, we treated RVFV MP-12 with LJ001 or DMSO and repurified the virus via banding through a density gradient. Each fraction was processed for either Western blotting or infectivity determination by plaque assays. Fig. 4A shows that the RVFV envelope and nucleocapsid proteins banded at the same buoyant density regardless of LJ001 treatment, although there may be a slight loss of membrane (GN/GC) or nucleocapsid (N) proteins in some LJ001-treated samples. Vehicle control (DMSO-treated) fractions remained fully infectious, but fractions treated with LJ001 were completely noninfectious despite the obvious presence of intact virions in lane 9 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

LJ001-treated virions remain grossly intact. (A) RVFV MP-12 was treated with 10 μM LJ001 or 2.5% DMSO for 20 min at 25 °C and banded across an iodixanol density gradient. One portion from each fraction was subjected to immunoblotting for the envelope (GC/GN) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, and the other was used to conduct a plaque assay measuring infectivity. (B) Fractions from A were used to conduct a plaque assay measuring infectivity (white bars, DMSO; interleaved solid bars (not visible), LJ001). Note that the solid bars representing LJ001-treated viruses cannot be seen in the figure and represent at least a 5-log reduction in infectivity. Similar results were obtained upon repetition with RVFV as well as pVSV. (C) CHO cells stably expressing ephrinB2 were incubated with NiV-pVSV in the presence of 0.1% DMSO, 10 μM LJ001, or 40 nM soluble ephrin B2-Fc (EFN-B2) at 4 °C for 2 h. Cells were washed and fixed in 0.5% PFA; then bound viruses were detected with anti-NiV-F and quantified by flow cytometry. This panel is a graphical representation of raw histogram data from a representative experiment. (D) Sulforhodamine B-loaded liposomes (200 nm) were incubated with the indicated concentration of compound and assayed for fluorescent signal. Data were collected using a PTI QM4 fluorescence spectrophotometer at 25 °C (with constant stirring) with 4-nm excitation/emission bandpass at 560-nm excitation and 582-nm emission (counts ×100,000).

Our results indicated that the envelope glycoproteins of LJ001-treated RVFV and pVSV remain associated with the virus, albeit the virus itself remains noninfectious (Fig. 4 A and B). To see if LJ001-treated virions retain conformationally intact envelope glycoproteins, we performed a virion–cell binding assay by incubating NiV-pVSV viruses, in the presence or absence of LJ001, with CHO cells stably expressing the NiV receptor, ephrinB2 (28 –30) and then assayed for virus binding with anti-NiV-F polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 4C) (29, 31). The ability of soluble ephrinB2 to compete for virus–cell binding demonstrates the specificity of the assay (Fig. 4C). To test further if LJ001 compromises membrane integrity, we loaded liposomes with the fluorescent sulforhodamine B (SulfoB) dye and incubated them with the indicated concentrations of LJ001 while looking for SulfoB leakage (Fig. 4D). No SulfoB leaked from the liposomes, indicating that LJ001 did not compromise membrane integrity sufficiently to allow leakage of molecules the size of SulfoB (540 Da). In toto, these assays indicate that LJ001-treated virions remain grossly intact and retain conformationally intact envelope glycoproteins.

LJ001 Affects Viral–Cell Fusion but Not Cell–Cell Fusion.

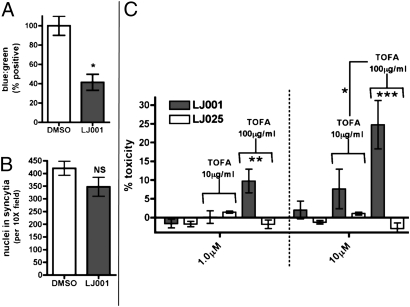

Because the viral envelope appears to remain functionally intact, we investigated if LJ001 inhibits virus–cell fusion. To do so, we developed a NiV matrix-based virus-like particle entry assay in which virus–cell fusion is mediated by cognate NIV-F and -G proteins, and entry is monitored only by cytosolic delivery of a reporter protein fused to the NiV matrix protein, circumventing the need for viral transcription or translation (32). Fig. 5A shows that LJ001 inhibited cytoplasmic delivery of this β-lactamase matrix fusion protein, suggesting that LJ001 acts before viral entry or completion of virus–cell fusion. However, LJ001 clearly did not inhibit cell–cell fusion (syncytia formation) mediated by the same NiV-F and -G proteins (Fig. 5B). This finding underscores the existence of fundamental differences between virus–cell and cell–cell fusion and provides additional evidence that LJ001 exploits biophysical or physiological differences between virus and cell membranes.

Fig. 5.

LJ001 affects viral–cell fusion but not cell–cell fusion. (A) NiV virus-like particles, pretreated with 10 μM LJ001 or DMSO, were used to infect Vero cells preloaded with CCF2-AM substrate and assayed for infection via flow cytometry (32). Data are shown as normalized ratios of blue:green cells (±SEM). (B) Vero cells were transfected with NiV-F and -G expression vectors, incubated overnight in media with 10 μM LJ001 or 0.1% DMSO, DAPI stained, and assayed visually for nuclei in syncytia by counting and averaging five 10× fields (±SD). (C) The treatment of cells with the fatty acid synthesis inhibitor TOFA increases relative toxicity of LJ001-treated cells. Vero cells were incubated with media containing the indicated concentration of TOFA in the presence of the indicated concentration of LJ compound for 24 h and then were measured for cellular toxicity using the Toxilight assay (Cambrex). Data represent n = four per goup in triplicate experiments. Data are normalized to 100% toxicity (indicated by 100% cell lysis) with toxicity of the indicated TOFA concentration subtracted as background. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

One obvious physiological difference between viral and cellular membranes is the bioreparative capacity of the latter. We hypothesized that LJ001 had no effect on cell–cell fusion because the cell was able to repair any putative damage LJ001 may have exerted on its membranes. If this hypothesis is true, treatment of cell lines with inhibitors of biogenic repair mechanisms may exacerbate the toxic effect of LJ001 at otherwise nontoxic antiviral concentrations. Indeed, 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid (TOFA), an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis, exhibited synergistic toxicity in LJ001- but not LJ025-treated cells ( Fig. 5C ). Recall that LJ025 is an inactive analog that binds to lipid membranes but does not have antiviral activity.

Discussion

Here we report on a small molecule, LJ001, that binds to lipid membranes and inhibits virus–cell fusion and entry of many enveloped viruses. LJ001 binds to both viral and cellular membranes and inhibits virus–cell but not cell–cell fusion. Because our studies indicate that its inhibitory effect cannot be attributed solely to membrane binding or curvature (Figs. S4 and S6), we propose that LJ001 probably exploits some physiological difference between static viral membranes and biogenic plasma membranes. Indeed, inhibitors of fatty acid biosynthesis that impinge on the membrane reparative capacity of the cell exacerbate LJ001’s toxicity, suggesting that cells require their biogenic reparative abilities to overcome the toxic effects of LJ001. In contrast, static viral membranes do not have the ability to repair themselves, thus leaving the viral membrane susceptible to “inactivation” by LJ001.

LJ001 intercalates into lipid bilayers, probably via the phenyl ring on its nonpolar end, and positions the pharmacophore on the opposite polar end for activity. Notably, a thioxo functionality is required for antiviral activity, presumably because of its increased reactivity versus the oxo analog. It is possible that an activation of the thioxo functionality occurs to cause damage in the lipid environment of the virus or cell. This damage to the viral membrane may affect the fluidity/rigidity of the lipid bilayer and compromise its ability to undergo the positive-to-negative curvature transitions required for productive fusion and may represent a mechanism of viral inhibition that likely targets a broad-spectrum of enveloped viruses.

The actual efficacy of LJ001 for the prophylactic, postexposure, or therapeutic treatment of enveloped viral diseases probably will depend on formulation and pharmacological considerations as well as on the pathogenic profile of the virus. Thus, we conducted preliminary Ebola postchallenge protective efficacy experiments by dosing once daily with LJ001 in 100% DMSO at 50 mg/kg i.p. after lethal challenge with maZEBOV and initially were discouraged when LJ001 did not show efficacy in this postchallenge assay (Fig. S7A). We subsequently developed a liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/tandem MS method for quantifying LJ001 in serum, and analysis of the pharmacokinetic data we eventually obtained (Fig. S7B) explains this failure. Serum concentrations of LJ001 did not approach in vitro IC50 concentrations (∼1.0 μM) until 2 h after i.p. injection, and the biological half-life of the compound appears to be about 4 h. Clearly, once-daily dosing was not sufficient to maintain therapeutic steady-state plasma concentrations of LJ001. However, our results suggest that reasonable serum concentrations can be obtained if formulation, potency, or pharmacokinetic properties can be improved (Table S1).

An added advantage that underlies LJ001’s lipid-based mechanism of action might be its ability to limit the development of resistance. It is encouraging that after passaging HIV-1 for 4 weeks in subneutralizing concentrations of LJ001, we have obtained no evidence of decreased sensitivity to LJ001 (Fig. S8), although the true extent by which LJ001 may limit viral resistance remains to be determined. Finally, even if the pharmacokinetic properties of LJ001 cannot be optimized for parenteral administration, one can envision the formulation of LJ001 as a topical microbicide against mucosally transmitted, lipid-enveloped viruses, such as HIV and HSV-1 and -2, or as a microbicide inhalant against respiratory viruses, such as influenza A (analogous to the use of zanamivir).

In summary, we have described a broad-spectrum small-molecule inhibitor that prevents enveloped virus entry at a step after virus binding but before virus–cell fusion. This compound, an aryl methyldiene rhodanine derivative termed “LJ001,” acts on the virus and not on the cells. LJ001’s lack of overt cytotoxicity and apparent specificity for inhibiting virus–cell fusion and entry reflects its ability to exploit the therapeutic window that exists between the biogenic properties of cellular plasma membranes versus those of static viral membranes.

Materials and Methods

Pseudotyped Virus Production and Infection.

Pseudotyped VSV viruses were prepared and assayed for infection as previously described (26, 29 –31). Unless indicated otherwise, all infections were performed in 1% FBS in PBS. All pretreatments with compound were carried out at 25 °C for 10 min, although the pretreatment regimen among different laboratories and viral infection methodologies can vary slightly. However, changes in the pretreatment temperature and duration had no effect on LJ001’s antiviral activity (Fig. S9).

Viral Strains.

We used the following viral strains: Vesicular stomatitis Indiana; Ebola Zaire/(ma)Zaire; Marburg Musoke/Ravn; Junín Romero; Rift Valley fever ZH501 and MP-12 (vaccine strain); LaCrosse prototype; Omsk hemorrhagic fever Guriev; Russian spring–summer encephalitis Sofjin; Sendai Enders; Human parainfluenza type 3 C-243; HIV- JRCSF/YU2; Murine leukemia F57; Cowpox Brighton; Vaccinia VTF1.1; Adenovirus Ad5-eGFP; Coxsackie B eGFP (33); Influenza A WSN H1N1; Nipah Malaysia; Yellow fever Asibi; Hepatitis C JFH1; West Nile virus New York 385–99; Reovirus (mammalian orthoreovirus) type 3 Dearing; and Newcastle disease rNDV/F3aa-GFP. Poxviridae stocks likely consist of infectious single-membrane intracellular-membrane virions rather than double-membrane extracellular enveloped virions.

In Vitro Toxicity Assays.

Cellular toxicity was assayed using adenylate kinase (Cambrex Corp.), lactate dehydrogenase (Takara Bio Inc.), and Alamar Blue (Invitrogen) cytotoxicity assays as per the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Cell–Cell Syncytia Assay.

Syncytia assays were conducted as described previously (31, 26).

Virion Purification.

Unless otherwise indicated, virus particles were purified through a 20% sucrose cushion for at least 1 h at 110,000 × g. For the live VSV repurification experiments, viruses were pelleted through a 10% sucrose cushion.

Preparation of LJ-Series Compounds.

Compounds were resuspended initially in 100% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 10 mM. LJ001 and further LJ-series compounds were prepared as described in the literature.

Manufacture of Recombinant Liposomes.

Recombinant unilammelar liposomes (7:3 molar ratio of phosphatidylcholine (PC):cholesterol) were manufactured by Encapsula Nanosciences, LLC.

In Vivo Toxicity Assay.

Female BALB/c mice were dosed with DMSO, 20/mg/kg, or LJ001, 50 mg/kg, by oral gavage or i.p. injection as described in the text. Full toxicology studies were performed by Charles River Laboratories.

Statistical Analyses.

All P values were calculated using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test unless indicated otherwise. The 95% confidence interval in Table S1 was calculated using GraphPad PRISM regression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Nayak and S. Barman for Influenza A testing, T. S. Dermody for Reovirus T3D, Peter Palese for rNDV-GFP, and K. Esham and J.C. Johnson (US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases) for BSL-4 assistance. We also thank I.S.Y. Chen, R. W. Doms, and K. A. Bradley for thoughtful discussion and members of the Lee laboratory, and especially F. Vigant, for both thoughtful conversation and review of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI065359, AI069317, AI070495, and AI082100 (to B.L.), UCLA Center for Aids Research Grant AI028697, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (B.L., S.P.W.), a March of Dimes Research Grant (to A.M.), the California NanoSystems Institute (R.D.), UCLA Microbial Pathogenesis Training Grant AI07323, a Warsaw Fellowship Endowment (M.C.W.), and Rheumatology Training Grant AR053463 (to P.W.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0909587107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tam RC, Lau JY, Hong Z. Mechanisms of action of ribavirin in antiviral therapies. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2001;12:261–272. doi: 10.1177/095632020101200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekisz J, Schmeisser H, Hernandez J, Goldman ND, Zoon KC. Human interferons alpha, beta and omega. Growth Factors. 2004;22:243–251. doi: 10.1080/08977190400000833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Veer MJ, et al. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:912–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen GC. Viruses and interferons. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong Z, Cameron CE. Pleiotropic mechanisms of ribavirin antiviral activities. Prog Drug Res. 2002;59:41–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8171-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burroughs T, Knobler S, Lederberg J. The Emergence of Zoonotic Diseases: Understanding the Impact on Animal and Human Health - Workshop Summary from Board on Global Health, Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chernomordik LV, Zimmerberg J, Kozlov MM. Membranes of the world unite! J Cell Biol. 2006;175:201–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMahon HT, Gallop JL. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 2005;438:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nature04396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. Protein-lipid interplay in fusion and fission of biological membranes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:175–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin I, Ruysschaert JM. Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits vesicles fusion induced by the NH2-terminal extremity of SIV/HIV fusogenic proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1240:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razinkov VI, Melikyan GB, Epand RM, Epand RF, Cohen FS. Effects of spon-taneous bilayer curvature on influenza virus-mediated fusion pores. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:409–422. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shangguan T, Alford D, Bentz J. Influenza-virus-liposome lipid mixing is leaky and largely insensitive to the material properties of the target membrane. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4956–4965. doi: 10.1021/bi9526903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Günther-Ausborn S, Praetor A, Stegmann T. Inhibition of influenza-induced membrane fusion by lysophosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29279–29285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langosch D, Brosig B, Pipkorn R. Peptide mimics of the vesicular stomatitis virus G-protein transmembrane segment drive membrane fusion in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32016–32021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langosch D, Hofmann M, Ungermann C. The role of transmembrane domains in membrane fusion. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:850–864. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bobardt MD, et al. Hepatitis C virus NS5A anchor peptide disrupts human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5525–5530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801388105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G, et al. A virocidal amphipathic alpha-helical peptide that inhibits hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3088–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712380105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holthuis JC, Levine TP. Lipid traffic: Floppy drives and a superhighway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:209–220. doi: 10.1038/nrm1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma membrane disruption: Repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:697–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeil PL, Terasaki M. Coping with the inevitable: How cells repair a torn surface membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E124–E129. doi: 10.1038/35074652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meldolesi J. Surface wound healing: A new, general function of eukaryotic cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2003;7:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kent C. Eukaryotic phospholipid biosynthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:315–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koval M, Pagano RE. Lipid recycling between the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments: Transport and metabolism of fluorescent sphingomyelin analogues in cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2169–2181. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sleight RG, Pagano RE. Transport of a fluorescent phosphatidylcholine analog from the plasma membrane to the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:742–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.2.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman RM, Mellman IS, Muller WA, Cohn ZA. Endocytosis and the recycling of plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levroney EL, et al. Novel innate immune functions for galectin-1: Galectin-1 inhibits cell fusion by Nipah virus envelope glycoproteins and augments dendritic cell secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;175:413–420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Nasiry S, Geusens N, Hanssens M, Luyten C, Pijnenborg R. The use of Alamar Blue assay for quantitative analysis of viability, migration and invasion of choriocarcinoma cells. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1304–1309. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negrete OA, Chu D, Aguilar HC, Lee B. Single amino acid changes in the Nipah and Hendra virus attachment glycoproteins distinguish ephrinB2 from ephrinB3 usage. J Virol. 2007;81:10804–10814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00999-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negrete OA, et al. EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature. 2005;436:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negrete OA, et al. Two key residues in ephrinB3 are critical for its use as an alternative receptor for Nipah virus. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schowalter RM, et al. Rho GTPase activity modulates paramyxovirus fusion protein-mediated cell-cell fusion. Virology. 2006;350:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf MC, et al. A catalytically and genetically optimized beta-lactamase-matrix based assay for sensitive, specific, and higher throughput analysis of native henipavirus entry characteristics. Virol J. 2009;6:119. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feuer R, Mena I, Pagarigan R, Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Cell cycle status affects coxsackievirus replication, persistence, and reactivation in vitro. J Virol. 2002;76:4430–4440. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4430-4440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.