Abstract

Tumor growth depends on nutrients and oxygen supplied by the vasculature through angiogenesis. Here, we show that the chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II (COUP-TFII), a member of the nuclear receptor family, is a major angiogenesis regulator within the tumor microenvironment. Conditional ablation of COUP-TFII in adults severely compromised neoangiogenesis and suppressed tumor growth in xenograft mouse models. In addition, tumor growth and tumor metastasis were also impaired in a spontaneous mammary-gland tumor model in the absence of COUP-TFII. We showed that COUP-TFII directly regulates the transcription of Angiopoietin-1 in pericytes to enhance neoangiogenesis. Importantly, provision of Angiopoietin-1 partially restores the angiogenic defects exhibited by the COUP-TFII–deficient mice, which supports the notion that COUP-TFII controls Angiopoietin-1/Tie2 signaling to regulate tumor angiogenesis. Because COUP-TFII has little impact on normal adult physiological function, our results raise an interesting possibility that inhibition of COUP-TFII may offer a therapeutic approach for anticancer intervention.

Keywords: angiopoietin-1/Tie2, tumor progression and metastasis

Angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels from a preexisting vessel network through a combination of sprouting, proliferation, and remodeling processes (1). It is generally believed that factors promoting or inhibiting angiogenesis are in check to counterbalance each other so as to maintain the quiescent status in adulthood. However, uncontrolled angiogenesis is often observed under pathological conditions, such as retinopathy and cancer (2). The central role of angiogenesis in tumor progression and metastasis is now well-appreciated and is governed by a balance between stimulators and inhibitors of angiogenesis (3, 4). Without persistent angiogenesis, tumor cells will undergo apoptosis or become necrotic. Thus, the so-called “angiogenic switch,” which is the induction of tumor vasculature, is believed to be a key step for the sustained growth of tumors (1).

It has been known that angiogenesis depends on shear stress and coordinated interactions between vascular growth factors (e.g., VEGF, Angiopoietin, bFGF), intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., Notch), and intercellular contacts (2, 5 –10). VEGF is a major mediator of angiogenesis, which transmits its signals primarily through binding to its receptor VEGFR-2, a receptor tyrosine kinase, on the surface of endothelial cells (7, 11). Emerging evidence also suggested that the cross-talk between endothelial cells and the surrounding mesenchymal cells is critical for the differentiation of mural cells as well as for the remodeling and maturation of the vasculature (12). Inappropriate recruitment of pericytes/vascular smooth muscle cells because of the disruption of either PDGF-B or Angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) signaling results in vascular abnormalities (5, 12, 13).

Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II (COUP-TFII), a member of the nuclear hormone-receptor superfamily (14), is highly expressed in the mesenchyme and plays critical roles during mouse development (15 –19). Here, we show that ablation of COUP-TFII in adult mice markedly compromised neoangiogenesis, suppressed tumor growth in xenograft mouse models, and impaired tumor metastasis in a spontaneous mouse mammary tumor models. Thus, our findings reveal COUP-TFII as an important regulator for pathologic neovascular response and suggest a target for anti-angiogenic therapy.

Results

Essential Role of COUP-TFII in Adult Angiogenesis.

We have previously shown that COUP-TFII null mutants exhibit angiogenesis defects during embryonic development (19). However, the role of COUP-TFII in adult and pathologic angiogenesis remains undefined. To address this question, we exploited a tamoxifen-inducible knockout system by crossing ROSA26CRE-ERT2/+ mice (20) with COUP-TFIIflox/flox (F/F) mice to generate ROSA26CRE-ERT2/+, COUP-TFIIflox/flox (Cre/+; F/F) mice. COUP-TFII expression in these mice was maintained in the absence of tamoxifen treatment. On administration of tamoxifen, Cre recombinase is activated, and COUP-TFII is ablated as a consequence.

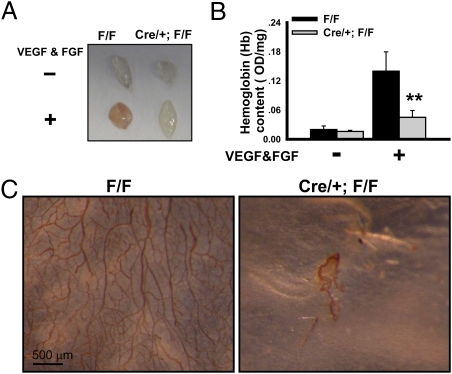

We then examined the angiogenic capacity in the COUP-TFII deficient mice by using a Matrigel-plug assay. Matrigel plugs containing bFGF and VEGF-A were implanted in control (F/F) and mutant (Cre/+; F/F) mice and recovered 14 days later. On gross examination, Matrigel specimens containing angiogenic factors recovered from control mice were reddish-brown (Fig. 1A). In sharp contrast, the plugs containing growth factors recovered from mutant mice were found to be much paler in comparison with those from the control mice (Fig. 1A). Consistent with this observation, total hemoglobin content, a measure of intact vessel formation that correlates with the amount of newly synthesized vessels, in the angiogenic factor-containing Matrigel was reduced ∼70% in the mutant mice (Fig. 1B). To ensure that this observable difference is because of a reduction in microvasculature density, we used the endothelial marker CD31 in whole-mounting immunostaining. It is clear that the vascular tree in the plugs implanted in the mutant mice is substantially less complex than that seen in the plugs of the control mice (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that loss of COUP-TFII significantly impaired adult neoangiogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Essential role of COUP-TFII in adult angiogenesis. (A) Control (F/F: COUP-TFflox/flox) and mutant (Cre/+; F/F: ROSA26CRE-ERT2/+/COUP-TFIIflox/flox ) mice were i.p. injected with tamoxifen to induce COUP-TFII deletion at 2 months of age. Matrigel plugs containing PBS or VEGF-A and FGF were implanted s.c. After 14 days, the plugs were removed and photographed. (B) Hemoglobin content of PBS or growth-factor–supplemented Matrigel from control and mutant mice (n = 10) is shown. (C) CD31 whole-mounted immunostaining images of angiogenic factor-containing plugs excised from control and mutant mice.

Inhibition of Tumor Growth in Mice Lacking COUP-TFII.

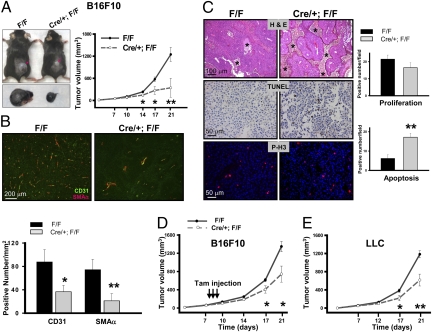

In light of the growth-factors–induced neoangiogenesis defects observed in adult mice lacking COUP-TFII, we postulated that COUP-TFII might play an important role in tumor angiogenesis as well as tumor growth. To address this issue, we s.c. grafted B16-F10 melanoma cells in control and mutant mice subsequent to deletion of COUP-TFII at 2 months of age. Before examining the role of COUP-TFII on ex vivo tumor growth, we performed double immunostaining of COUP-TFII with CD31 (endothelial cells) and SMAα (Pericytes) to monitor COUP-TFII deletion efficiency. Our immunostaining results revealed a strong COUP-TFII expression in control endothelial (arrow) and vascular smooth-muscle cells (arrowhead), whereas such expression was not detected in the mutant mice, indicating that COUP-TFII is efficiently deleted (Fig. S1A). Subsequently, tumor growth was monitored in control and COUP-TFII deficient mice. Fig. 2A shows that the tumor size and tumor growth rate in mutant mice are substantially reduced compared with that seen in control mice. In line with adult angiogenesis defects displayed by the loss of COUP-TFII, the density of both vessels and pericytes in the tumors was greatly reduced in the mutant mice in comparison with the controls, indicating that COUP-TFII is essential for tumor angiogenesis (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1B). The angiogenesis defects displayed by the mutant mice suggested that tumor cells might be deprived of nutrients and oxygen and therefore, undergo apoptosis. Consistent with this notion, H&E staining illustrated the presence of a substantial number of islands of viable tumor cells surrounded by necrotic tissue in the tumors from mutant mice but a smaller number of islands in the tumors of the control mice (Fig. 2C, asterisks). TUNEL assays further revealed that the tumor regions have significantly higher numbers of apoptotic cells in the mutant mice in comparison with the control mice (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that COUP-TFII is indispensable for angiogenesis to sustain the survival of tumor cells. In contrast, the slight reduction in tumor-cell proliferation was not statistically significant as shown by phosphorylated-H3 and Ki-67 immunostaining (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1C).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of tumor growth in mice lacking COUP-TFII. (A) After COUP-TFII is ablated at 2 months of age, F/F (control) and Cre/+; F/F (mutant) mice were s.c. grafted with B16F10 melanoma cells, and the rate of tumor growth was measured at the indicated time (n = 15). (B) Immunofluorescence for CD31 and SMAα on melanoma tumor sections from control and mutant mice are shown. The graph shows the positive numbers of CD31 and SMAα positive signals per square millimeter (n = 5). (C) H&E staining, TUNEL assay, and Phospho-H3 staining in B16F10 tumor sections from control and mutant mice. Quantitative results of tumor-cell proliferation and apoptosis are shown (Lower). (D) After the melanoma tumors had reached the size of approximately 50 mm3, tamoxifen was injected to induce the COUP-TFII deletion. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated time (n = 15). (E) The tumor-growth rate of LLC in control and mutant mice (n = 15) is shown.

To assess whether or not the absence of COUP-TFII can attenuate tumor growth subsequent to tumor initiation, COUP-TFII was ablated after the melanoma tumors had reached a certain size. As shown in Fig. 2D, tumor-growth rate was still substantially attenuated in the mutant mice in comparison with the control mice, suggesting that COUP-TFII is important for both initiation and continued expansion and maintenance of angiogenic process.

To address if angiogenic defects exerted by the loss of COUP-TFII are a general theme independent of cancer-cell types, we extended the above observation and grafted Lewis lung carcinoma cells (LLC) in COUP-TFII deficient and control mice in a similar manner. As expected, tumor growth is compromised in an analogous manner as that seen for the xenograft of the B16F10 melanoma cells (Fig. 2E). Taken together, the above results strengthen the notion that angiogenesis defects displayed by COUP-TFII mutants hamper tumor growth.

COUP-TFII Promotes Mammary Tumorigenesis and Metastases in Vivo.

To further investigate whether or not COUP-TFII is important for tumor growth in vivo, we took advantage of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-Polyoma Middle T antigen (PyMT) transgenic mice as a spontaneous tumor model to investigate the role of COUP-TFII in mammary-gland tumorigenesis. The expression of PyMT in mammary epithelial cells induces rapid development of multifocal mammary adenocarcinomas at nearly 100% frequency (21). Female PyMT+/−/COUP-TFIIflox/flox (PyMT; F/F) and PyMT+/−/ROSA26CRE-ERT2/+/COUP-TFIIflox/flox (PyMT; Cre/+; F/F) mice were generated, and tamoxifen was administered to induce the deletion of COUP-TFII at the age of 5 weeks.

Whole-mount inguinal mammary glands isolated from either 5-week-old PyMT; F/F or PyMT; Cre/+; F/F mice were phenotypically the same without tamoxifen treatment. The ductal nodules and ductal hyperplasia were indistinguishable between the two genotypes, indicating that tumor initiation and progression were the same before deletion of COUP-TFII (Fig. S2A). Upon administration of tamoxifen, COUP-TFII was efficiently deleted in the mammary tumors of mutant mice as shown by Western-blotting analysis (Fig. S2B). The efficiency of deletion was further confirmed by immunostaining using COUP-TFII–specific antibody, where COUP-TFII was deleted in the stromal cells (Fig. S2C).

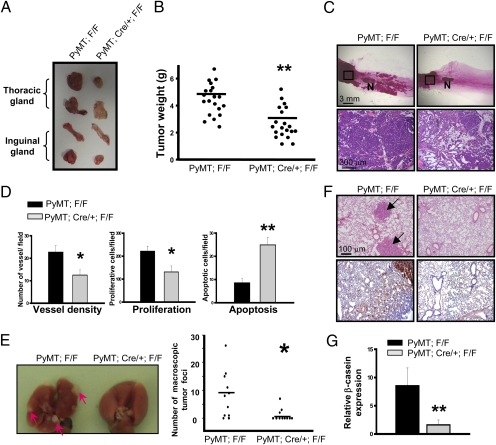

During 4.5 months of follow-up research, we found that the progression of mammary tumors was attenuated in COUP-TFII deficient mice. At 4.5 months of age, mammary-gland tumors in the mutant female mice were much smaller than those detected in control mice (2.6292 ± 0.48 g versus 4.6958 ± 0.38 g; Fig. 3 A and B). Morphological analysis of the inguinal mammary glands by whole-mount staining in situ and H&E staining showed that control mammary glands developed multifocal mammary tumors in the area between the nipple and lymph node (distal ducts region), whereas tumors were largely absent in the mutant glands (Fig. 3C). In addition, although extensive mammary adenocarcinomas developed in the more proximal duct region in mice of both genotypes, the tumor-free stromal tissues were much more abundant in mutant mammary glands (Fig. 3C), indicating that tumor malignancy was less advanced in COUP-TFII–deficient mice. In addition, similar intensity of PyMT staining argued against the possibility that the differences in mammary-gland tumorigenesis between control and mutant mice were attributed to different expression levels of the MMTV-PyMT transgene in COUP-TFII mutants (Fig. S2D).

Fig. 3.

COUP-TFII promotes mammary tumorigenesis in vivo. (A) Image of whole thoracic and inguinal mammary glands excised from 18-week-old PyMT; F/F and PyMT; Cre/+; F/F mice. COUP-TFII was deleted at the age of 5 weeks old. (B) Total mammary-tumor burden of control and mutant mice is shown (n = 20). (C) Carmine alum-stained whole-mount mammary glands from control and mutant mice at the age of 4.5 months. The boxed areas were sectioned and subjected to H&E staining (Lower). N, lymph node. (D) Sections were immunostained with CD31, cleaved caspase-3, or Ki-67 antibody. Quantification results show the vessel density, tumor-cell proliferation, and apoptosis (n = 6). (E) The image shows the typical appearance of metastatic foci within the control lung as indicated by the arrows. The number of visible metastatic foci was counted (Right). (F) H&E-stained lung sections were prepared from control and mutant mice. Arrows indicate tumor foci. Microscopic tumors in the lungs were indicated by immunostaining with PyMT antibody. (G) The β-casein mRNA content in lungs from control and mutant mice was quantified by qRT-PCR analysis (n = 6).

Next, we assessed whether or not the suppression of tumor progression in mutant mice was caused by angiogenic defects. Microvessels in the mammary tumors were evaluated by immunostaining with CD31 antibody (Fig. S3 and Fig. 3D). In agreement with the previous results, there was a substantial decrease in vascular density in the tumors of mutant animals, which contributes to the reduction of proliferation and survival of tumor cells indicated by Ki-67, phosphorylated-H3, and cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining (Fig. S3); the results are quantified in Fig. 3D. These data suggest that the loss of COUP-TFII leads to angiogenesis defects and subsequent reduction of tumor growth.

Given the emerging body of evidences that documented that angiogenesis is important for tumor metastasis to distal organs, we further asked whether or not metastasis was also inhibited by the loss of COUP-TFII. To address this, we examined the frequency and extent of lung metastasis in control and mutant mice of the PyMT breast-tumor model. The incidences of macroscopic tumor foci on the lung surface were observed in 82% (9 of 11) of control mice and 27% (3 of 11) of COUP-TFII–deficient mice (Fig. 3E). In addition, the number of macroscopic foci in the mutant animal was significantly decreased (Fig. 3E Right). Similarly, we also found a substantial decrease of microscopic tumor in the mutant lungs indicated by PyMT staining (Fig. 3F). In accordance, qRT-PCR analysis showed that COUP-TFII–deficient lung samples had significantly fewer transcripts of β-casein mRNA, which encodes a milk protein expressed specifically in the mammary epithelial cells (Fig. 3G). Taken together, these results indicate that ablation of COUP-TFII suppresses metastases of mammary tumors to the lung.

Ang-1 Is Directly Regulated by COUP-TFII to Modulate Angiogenesis.

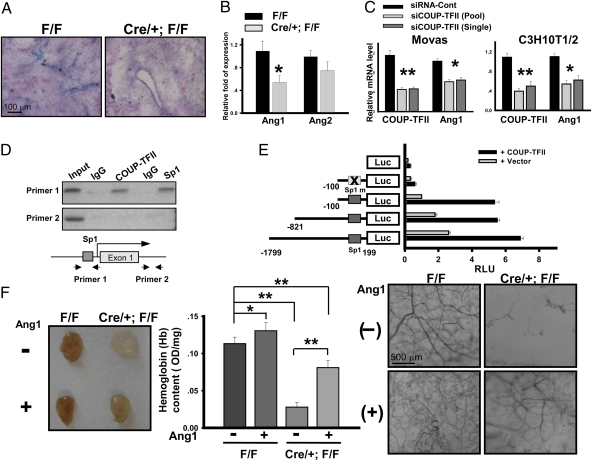

A major unanswered question is what are the target genes that are regulated by COUP-TFII to modulate angiogenesis. Notably, COUP-TFII was not expressed in tumor cells, suggesting that COUP-TFII might play roles within the tumor microenvironment. It is known that Ang-1 is expressed in pericytes surrounding blood vessels, and it serves as a pericyte-derived paracrine signal for the endothelium to increase vascular branching and remodeling (5, 22). Because we showed previously that the expression of Ang-1 is down-regulated in the COUP-TFII null mutant during embryonic development by an undefined mechanism (19), we asked whether or not the apparent angiogenic defect in the adult was contributed by the consequence of down-regulation of Ang-1 expression. Our in situ hybridization analysis revealed that Ang-1 was expressed in a vasculature-like pattern in the tumors from control mice (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Ang-1 expression level was substantially reduced in the tumor regions of COUP-TFII–deficient mice (Fig. 4A). In accordance, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that there was a 50% decrease of Ang-1 transcripts in the melanoma tumors from mutant mice compared with control mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the expression of Ang-2, a naturally occurring competitive antagonist for Ang-1 (23), did not differ significantly between control and COUP-TFII mutant mice (Fig. 4B). To further validate this regulation, we used siRNA to knockdown COUP-TFII expression in mouse aorta vascular smooth muscle cells (Movas) and C3H10T1/2 fibroblast. As shown in Fig. 4C, depletion of COUP-TFII resulted in decreased Ang-1 expression in both cell lines.

Fig. 4.

Ang-1 is directly regulated by COUP-TFII to modulate angiogenesis. (A) In situ hybridization of Ang-1 expression in B16F10 tumor sections from control and mutant mice. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Ang-1 and Ang-2 expression in the melanoma tumors from control and mutant mice (n = 6). Expression levels were normalized with CD31 transcript. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of Ang-1 transcripts in Movas and C3H10T1/2 fibroblast cells. (D) ChIP analysis showed that COUP-TFII and Sp1 bind to the region containing Sp1-binding sites in Ang-1 promoter (Top). The region in the first intron serves as a control (Middle). (E) Relative luciferase activity of Ang-1 promoter-driven reporter with or without cotransfection of COUP-TFII is shown. (F) Representative photos are shown of Matrigel plugs containing bFGF + VEGF-A or bFGF + VEGF-A + Ang-1 (Left). Hemoglobin content of the plugs was shown (n = 10; Center). Vascularization was visualized by CD31 whole-mount staining (Right).

We and others have previously shown that COUP-TFII activates NGFI-A, insulin-like growth factor-1, and HIV LTR promoter activity by tethering to specificity protein 1, which then induces the recruitment of coactivators to enhance the expression of target genes (24 –26). Mutation of Sp1 binding sites or knockdown of Sp1 in cells abolished the COUP-TFII–dependent enhancement of target gene expression, indicating that positive regulation of downstream targets by COUP-TFII is mediated through direct interaction with Sp1 (24, 25). Therefore, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to determine whether or not COUP-TFII regulates Ang-1 expression in a Sp1-dependent manner. ChIP analysis revealed that both COUP-TFII and Sp1 occupy an Ang-1 promoter region containing clustered and conserved Sp1 binding sites (Fig. 4D). Consistent with this observation, cotransfection of COUP-TFII enhanced Ang-1 promoter-driven Luciferase-reporter activity, whereas mutation of the conserved and closely clustered Sp1 sites at the Ang-1 promoter abolished the regulation of Ang-1 promoter activity by COUP-TFII, indicating that COUP-TFII directly regulates Ang-1 expression in a Sp1-dependent manner (Fig. 4E).

To determine whether or not the reduced expression of Ang-1 is responsible for the impaired tumor angiogenesis in mutant mice, we examined if the angiogenesis defects exhibited by COUP-TFII–deficient mice could be rescued by supplementing with Ang-1. Indeed, we observed that the addition of Ang-1 to the Matrigel plug partially restored angiogenic responses in the mutant mice (Fig. 4F). Both hemoglobin content and vessel-tree complexity were significantly increased to a greater extent in the Ang-1–rescued mutant plugs compared with the mutant plugs lacking Ang-1. These results suggest that reduced Ang-1 in the mutant mice is in part responsible for the angiogenesis defect displayed by COUP-TFII mutant mice.

Discussion

In recent years, the development of angiogenesis inhibitors has focused on the VEGF/VEGFR-2 signals. These inhibitors have shown promising efficacy in the clinic in the treatment of tumors and ocular diseases. However, because of the eventual resistance and toxic side effects (4), the identification of additional angiogenesis-targeted approaches is highly desirable. Our results reveal a central role of COUP-TFII in tumor angiogenesis through its regulation of a pericyte-derived paracrine signal for the endothelium within the tumor microenvironment. As a consequence, conditional ablation of COUP-TFII in mice significantly suppressed tumor progression and metastasis. Interestingly, recent structural analysis of COUP-TFII revealed a potential ligand-binding pocket within the putative ligand-binding domain of COUP-TFII (27). These findings suggest that the function of COUP-TFII could potentially be regulated by ligands, and this strengthens the notion that COUP-TFII could be a promising therapeutic target in future intervention for cancer therapy.

In the kidney, there was no observable glomerular damage in COUP-TFII mutant mice, because the glomerular structure, Mesangial cell, and vessel density seemed to be normal in the mutant kidney (Fig. S4 A and B). This finding is in contrast to that observed by the inhibition of the VEGF signaling pathway, which results in swelling and detachment of glomerular endothelial cells and disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier (28). Furthermore, adult mice lacking COUP-TFII appeared to be largely normal and did not display the visible defects in the adult vasculature. No obvious regression of preexisting vessel or vessel leakage was observed in the adult COUP-TFII–deficient mice (Fig. S4C), which indicates that COUP-TFII–mediated signaling is crucial during active neoangiogenesis but is not important for normal mature vessel maintenance. Presumably, targeting COUP-TFII would be different from the use of VEGF/VEGFR-2 angiogenic inhibitors, which leads to vessel regression and leakage (28).

Angiogenesis is induced by angiogenic growth factors secreted either by the tumor cells or the surrounding stroma cells (2). We showed that COUP-TFII directly regulates the transcription of Ang-1, which is expressed in pericytes and serves as a paracrine signal for the Tie2 receptor in the endothelium. It has been shown that transgenic over expression or systemic adenoviral delivery of Ang-1 in mice results in increased vascular branching and the remodeling of the primitive vascular network to a higher order structure (5, 29, 30). Because Ang-1 is not a mitogen, the increased vascular branching may arise from reinforcement of VEGF-induced angiogenesis (22). Indeed, our Matrigel plug results indicate that Ang-1 can synergize with VEGF to enhance angiogenesis. However, the role of Ang-1 in tumor angiogenesis is not entirely clear. Conflicting results have been reported in the literature regarding the role of the angiopoietin/Tie2 in tumor angiogenesis (31, 32). Our results support the notion that Ang-1 serves as a proangiogenic factor that positively regulates tumor angiogenesis. Notably, the expression level of Ang-2, a competitive antagonist of Ang-1 for the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 (23, 33), did not change significantly in the COUP-TFII mutant mice. Perhaps the discrepancy between various reports with respect to Ang-1 function in angiogenesis and vascular regression depends on the molecular balance between Ang-1 and Ang-2 and cellular context.

In summary, the present study highlights an important role of COUP-TFII in tumor angiogenesis within the tumor microenvironment. Our findings shed light on the basic molecular mechanisms involved in tumor angiogenesis and support COUP-TFII as a promising target for antiangiogenic therapy.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Experiments.

All experiments were approved by the Animal Center for Comparative Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. Mice used in this study were all backcrossed onto C57BL/6J background for more than seven generations. Generations of COUP-TFIIflox/flox mice and ROSA26CRE-ERT2 have been previously described (18, 20). To induce COUP-TFII deletion in the adult, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg of tamoxifen (Sigma) for 5 consecutive days at the age of 8 weeks. For mammary-gland mouse tumor model, MMTV-PyMT mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (21) and were crossed with either COUP-TFIIflox/flox or ROSA26CRE-ERT2; COUP-TFIIflox/flox mice to generate PyMT+/−/COUP-TFIIflox/flox or PyMT+/−/ROSA26CRE-ERT2/+/COUP-TFIIflox/flox. COUP-TFII was deleted at the age of 5 weeks.

Syngenic Tumor-Cell Implantation.

Tumor volumes were estimated by using the following formula: V = 0.52 × W2L.1 × 105 of B16F10 or 5 × 105 of LLC cells in 200 μl PBS were s.c. injected on the back of the mice.

Matrigel-Plug Assay.

Matrigel-plug assay was performed as previously described (10) by using the BD Matrigel Matrix (BD). For rescue experiments, Ang-1 (R&D) was added at a concentration of 20 ng/mL. For hemoglobin-content measurement, Matrigel plugs were digested with dispase (Sigma) and measured with a Drabkin reagent kit (Sigma).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry.

Primary antibodies used in this study are as follows: anti-COUP-TFII (Perseus Proteomics), CD31 (BD or Abcam), SMAα (Sigma), Ki-67 (BD), cleaved Caspase 3 (Cell signaling), phophorylated-H3 (Cell signaling), and PyMT (Stephen M. Dilworth, London, UK). In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (19).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR.

Total RNA were extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and reverse transcribed using Reverse Transcription Reagents (Invitrogen). A gene-expression assay was performed using the ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detector System, and all mRNA quantities were normalized against 18S RNA or CD31 transcript. The primers/probes used were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

ChIP Assays.

ChIP assays were performed using an assay kit (Millipore), monoclonal anti-COUP-TFII (Perseus Proteomics), and rabbit anti-Sp1 antibody (Millipore) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. The sequences of all primers used are available by request.

Image Quantification and Statistics.

Images were analyzed and quantified using National Institutes of Health Image J. Data represent mean ± SEM of representative experiments. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas Ludwig for ROSA26CRE-ERT2 mice, Dr. Peter Oettgen for Ang-1 reporter constructs, and Dr. Stephen M. Dilworth for the PyMT antibody. We also thank Dr. Li-Yuan Yu-Lee for her critical comments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL076448 (to S.Y.T.), DK059820 (to S.Y.T. and M.-J.T.), DK45641 (to M.-J.T.), and HD17379 (to M.-J.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0914619107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2039–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri C, et al. Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell. 1996;87:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones N, Iljin K, Dumont DJ, Alitalo K. Tie receptors: New modulators of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:257–267. doi: 10.1038/35067005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson MC, et al. Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845–1854. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson J, et al. Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-beta type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:1663–1673. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada K, et al. The PTEN/PI3K pathway governs normal vascular development and tumor angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2054–2065. doi: 10.1101/gad.1308805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancopoulos GD, et al. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindblom P, et al. Endothelial PDGF-B retention is required for proper investment of pericytes in the microvessel wall. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1835–1840. doi: 10.1101/gad.266803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Chick ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factors (COUP-TFs): Coming of age. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:229–240. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.2.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin J, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. Essential roles of COUP-TFII in Leydig cell differentiation and male fertility. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You LR, et al. Mouse lacking COUP-TFII as an animal model of Bochdalek-type congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16351–16356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507832102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You LR, et al. Suppression of Notch signaling by the COUP-TFII transcription factor regulates vein identity. Nature. 2005;435:98–104. doi: 10.1038/nature03511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takamoto N, et al. COUP-TFII is essential for radial and anteroposterior patterning of the stomach. Development. 2005;132:2179–2189. doi: 10.1242/dev.01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira FA, Qiu Y, Zhou G, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. The orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII is required for angiogenesis and heart development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1037–1049. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Luca C, et al. Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific LEPR-B transgenes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3484–3493. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: A transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim WS, Ho IA, Wong PE. Angiopoietin: A TIE(d) balance in tumor angiogenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:655–665. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maisonpierre PC, et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pipaón C, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. COUP-TF upregulates NGFI-A gene expression through an Sp1 binding site. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2734–2745. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim BJ, Takamoto N, Yan J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Chicken Ovalbumin Upstream Promoter-Transcription Factor II (COUP-TFII) regulates growth and patterning of the postnatal mouse cerebellum. Dev Biol. 2009;326:378–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohr O, Aunis D, Schaeffer E. COUP-TF and Sp1 interact and cooperate in the transcriptional activation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat in human microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31149–31155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruse SW, et al. Identification of COUP-TFII orphan nuclear receptor as a retinoic acid-activated receptor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurevich F, Perazella MA. Renal effects of anti-angiogenesis therapy: Update for the internist. Am J Med. 2009;122:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uemura A, et al. Recombinant angiopoietin-1 restores higher-order architecture of growing blood vessels in mice in the absence of mural cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1619–1628. doi: 10.1172/JCI15621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thurston G, et al. Angiopoietin 1 causes vessel enlargement, without angiogenic sprouting, during a critical developmental period. Development. 2005;132:3317–3326. doi: 10.1242/dev.01888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoeltzing O, et al. Angiopoietin-1 inhibits vascular permeability, angiogenesis, and growth of hepatic colon cancer tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3370–3377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shim WS, et al. Angiopoietin 1 promotes tumor angiogenesis and tumor vessel plasticity of human cervical cancer in mice. Exp Cell Res. 2002;279:299–309. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gale NW, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev Cell. 2002;3:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.