Abstract

The purpose of this study was to understand the nature of the causes underlying the senescence-related decline in skeletal muscle mass and performance. Protein and lipid oxidative damage to upper hindlimb skeletal muscle mitochondria was compared between mice fed ad libitum and those restricted to 40% fewer calories—a regimen that increases life span by ~30–40% and attenuates the senescence-associated decrement in skeletal muscle mass and function. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins, measured as amounts of protein carbonyls and loss of protein sulfhydryl content, and to mitochondrial lipids, determined as concentration of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, significantly increased with age in the ad libitum-fed (AL) C57BL/6 mice. The rate of superoxide anion radical generation by submitochondrial particles increased whereas the activities of antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in muscle homogenates remained unaltered with age in the AL group. In calorically-restricted (CR) mice there was no age-associated increase in mitochondrial protein or lipid oxidative damage, or in superoxide anion radical generation. Crossover studies, involving the transfer of 18- to 22-month-old mice fed on the AL regimen to the CR regimen, and vice versa, indicated that the mitochondrial oxidative damage could not be reversed by CR or induced by AL feeding within a time frame of 6 weeks. Results of this study indicate that mitochondria in skeletal muscles accumulate significant amounts of oxidative damage during aging. Although such damage is largely irreversible, it can be prevented by restriction of caloric intake.

Keywords: Aging, Oxidative stress, Free radicals, Caloric restriction, Skeletal muscle, Mitochondria, Protein oxidation

INTRODUCTION

Loss of mass and functional performance of skeletal muscles is one of the most prominent manifestations of senescence in animals [1–3]. The nature of the underlying causal factors is, however, poorly understood. One hypothesis postulates that accrual of molecular oxidative damage, induced by the reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as byproducts of oxygen utilization by aerobes, is a major causal factor for the age-related decreases in the functional capacity of various physiological systems [4–6].

A variety of studies suggest that mitochondria play a crucial role in the aging process because they are not only the main generators of the primary ROS namely, superoxide anion radical (O2 •−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), but also perhaps the most immediate targets of the oxidative damage inflicted by the ROS [6–8]. Age-associated increase in the rate of mitochondrial O2 •−/H2O2 generation [8–11] and the amount of oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins and DNA have been observed to increase in mammalian[12] and insect tissues [10,13]. Experimentally-induced oxidative damage to mitochondria has also been demonstrated to increase their rate of H2O2 generation [10,14]. In addition, the rates of mitochondrial O2 •−/H2O2 generation exhibit an inverse correlation with the life spans of different mammalian [15] and insect [16] species. A variety of decrements in mitochondrial respiratory activities, including the overall measure of performance, namely, the maximal rate of ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption, have also been detected during aging [17,18]. Together, results of such studies raise the possibility that mitochondrial damage may play a critical role in the senescence of tissues, including the skeletal muscles.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the extent to which mitochondrial oxidative damage is associated with aging of the skeletal muscles. The experimental design of this study is based on the rationale that if mitochondrial damage is indeed a causal factor in skeletal muscle aging, then the magnitude of such damage should decrease if the age-associated losses in muscle mass and function are experimentally attenuated, and vice versa.

In mammals, reduction in caloric intake, as compared to ad libitum intake, is the only experimental regimen known to markedly prolong life span and to attenuate and/or retard the progression of a variety of age-associated deleterious alterations [19,20]. For instance, a 40% reduction in caloric intake, as compared to the ad libitum-fed (AL), has been found to result in a 20–40% extension of average and maximum life spans of mice and rats [19]. One of the consistent functional consequences of caloric restriction (CR) is the delay or attenuation of age-related loss of motor capacity and muscle mass [21,22]. Therefore, if mitochondrial oxidative damage is a possible mechanism responsible for age-related loss in skeletal muscle functional capacity, then CR would be expected to delay or reduce the accrual of such damage, and vice versa.

Another goal of this study was to additionally understand the nature of the relationship between caloric intake and aging, by determining whether or not the effects of prolonged CR are reversible following a shift to the AL feeding regimen, and vice versa. The rationale is that it is presently unclear whether or not the consequences of CR involve deceleration in the rate of the primary processes underlying the age-associated losses, as opposed to acute beneficial effect on cellular functions that are reversible [23]. In order to differentiate these two possibilities, a crossover experiment was performed in which CR and AL mice of relatively advanced age were switched to the opposite dietary regimen for 6 weeks. If CR acts in a cumulative fashion to decelerate the rate of age-associated increase in oxidative damage, then changing of the dietary regimens for a relatively short period will be expected to have little effect. However, if effects of CR involve a reversible lowering of oxidative damage, then a decrease in oxidative damage will be expected to occur in AL mice following transfer to the CR regimen, and an increase in oxidative damage will be expected in CR mice following their transfer to the AL regimen. Results of this study indicate that CR prevents an age-related increase in mitochondrial oxidative to proteins and lipids and this effect is largely irreversible, and vice versa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All solvents used were of HPLC grade (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA), 2,6-di-tert-buty-lated-4-hydroxytoluene (BHT), 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ethylenedinitrilo-tetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA) was from Fisher Chemicals (Fisher Scientific).

Animals and Diets

The present study was conducted on male C57BL/6Nnia mice obtained from the National Institute on Aging caloric restriction colonies, maintained at the National Center for Toxicological Research (Jefferson, AR, USA). The mice were housed individually in 28 × 19 × 12.5-cm solid bottom polycarbonate cages with wire tops modified into two mouse units by insertion of a stainless steel divider. Beginning at 4 months of age, some of the mice were maintained on a calorically restricted regimen (CR) permitting daily access to 60% of the intake of a companion group of mice given ad libitum access (AL) to the diet (NIH-31 open formula diet, Purina Mills, Inc., Richmond, IN, USA). The CR mice were fed a special NIH-31 formulation, which was enriched in content of vitamins to balance intake between groups. The mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle, with the light portion beginning at 0600 h, and were kept under identical conditions following receipt at the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) Vivarium, with the exception that the CR mice were placed on a night feeding regimen in which they were fed at 2200 h, approximately 2 h prior to the acrophase of the normal circadian feeding cycle of the AL mice. The purpose of this procedure was to provide proper phasing of circadian cycles in the AL and CR groups. Mortality and body weight analyses for designated cohorts of AL and CR mice, maintained at National Center for Toxicological Research, have been published previously [12, 24].

For studies of the effects of age and CR, mice were maintained a minimum of 2-weeks within the UNTHSC Vivarium, whereupon they were euthanized by CO2 in-halation and skeletal muscle tissue samples were quickly dissected and homogenized for mitochondrial preparation. Reversibility studies were performed in groups of AL and CR mice aged 18–22 months, by assigning one-half of the mice in each group to receive the opposite diet condition for a period of 6 weeks. Following the 6-week adaptation period, the mice were euthanized and tissues processed as described. The 6-week adaptation period was selected based on data from a previous time-course study indicating complete reversal of the effect of CR on protein carbonyl content in the brain within this time frame [25].

Isolation of mitochondria

Skeletal muscle mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation as described by Trounce et al. [26]. Briefly, skeletal muscles from the upper hindlimb were homogenized in 10 volumes (w/v) of isolation buffer containing 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% BSA, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, at 4°C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min, the supernatant recovered and recentrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min. Thereafter, the supernatant was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 15 min, the resulting mitochondrial pellet resuspended in isolation buffer not containing BSA and recentrifuged at 8,000 × g for 15 min. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer without BSA and stored at −80°C. To prepare submitochondrial particles, mitochondria were suspended in 30 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and sonicated three times, each consisting of 30-s pulse burst, at 1 min intervals at 4°C. The sonicated mitochondria were centrifuged at 8,250 × g for 10 min to remove the unbroken organelles; the supernatant was recentrifuged at 80,000 × g for 45 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and stored at −80°C. Protein content was determined using the BCA protein assay from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Bovine serum albumin in a concentration range of 0–50 µg/ml was used as a standard.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS)

Formation of the MDA-TBA adduct was assessed as described by Wong et al. [27]. Briefly, 750 µl phosphoric acid solution (0.15 M) was added to 500 µl of mitochondrial suspension (containing 20 µM BHT and 2 mM EDTA) or to freshly prepared standards of malondialdehyde bis[diethyl acetyl] (Sigma), followed by the addition of 250 µl thiobarbituric acid (0.42 mM). After incubation for 60 min at 95°C in a water bath, the samples were placed on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 7,000 × g and content of TBARS in the supernatant was measured using a Perkin-Elmer LS-5B fluorometer (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) set to excite at 525 nm and emit at 550 nm. Concentrations were calculated using a standard curve.

Protein carbonyls

The carbonyl content of mitochondrial proteins was determined by HPLC following the procedure described by Shacter et al. [28]. A mixture of 100 µl of sample (~0.1 mg protein), 30 µl of SDS (30%, w/v), 15 µl of EDTA (10%, w/v), and 100 µl of DNPH (20 mM dinitrophenylhydrazine in 10% trifluoroacetic acid, w/v) was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Thereafter, the sample was neutralized with 2 M Tris and centrifuged at 7,200 × g for 5 min. An aliquot was chromato-graphed on a Zorbax GF-250 column (Rockland Technologies Inc., Chadds Ford, PA, USA) with 200 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, 1% SDS as mobile phase at a flow of 2 ml/min. The eluent was recorded simultaneously at 365 nm (Waters Associates model 440 absorbance detector) and 280 nm (Pharmacia LKB optical unit UV-1). Peak integration was performed between 3 and 6 min of retention time, corresponding to protein sizes between ~250 to ~20 kDa. For calculations, an extinction coefficient for DNP labeled carbonyl groups ϵ = 22,000 M−1cm−1 and for protein content ϵ = 50,000 M−1cm−1 was used.

Protein sulfhydryls

For the measurement of sulfhydryl groups in mitochondrial protein, 100 µl of sample (~50 µg protein) was mixed with 20 µl of SDS (30%), 15 µl of EDTA (10%), and 10 µl of DTNB (10 mM 5,5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid)) solution and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After centrifugation at 7,500 × g for 5 min, an aliquot was chromatographed on a Zorbax GF-250 column (Rockland Technologies Inc.) with 200 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, 1% SDS as mobile phase at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The Protein-S-TNB adduct was recorded at 340 nm (Waters Associates model 440 absorbance detector), whereas for protein the eluent was recorded at 280 nm (Pharmacia LKB optical unit UV-1). Peak integration was performed between 3 and 6 min of retention time, corresponding to protein sizes between ~250 to ~20 kDa. For quantification, maleic dehydrogenase labeled with DTNB was used as a standard.

Superoxide anion radical (O2 •−) generation

The rate of O2 •− generation by SMPs was measured as superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable reduction of acetylated ferricytochrome c [29], as described previously [15]. The reaction mixture contained 10 µM acetylated ferricytochrome c, 6 µM rotenone, 1.2 µM anti-mycin A, 100 units of SOD/ml (in the reference cuvette), and 10–100 µg SMP protein in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The reaction was started by the addition of 7.5 mM succinate and the reduction of acetylated ferricytochrome c was followed at 550 nm.

Antioxidative enzyme activities

Activities of the enzymes were measured in the supernatants of skeletal muscle homogenates, centrifuged at 600 × g. SOD activity was measured by the method of Spitz and Oberely [30]. Catalase was measured by the method of Luck [31]. Glutathione peroxidase was determined as described by Beutler [32].

Statistical analysis of data

Measures of oxidative damage were subjected to two-way analyses of variance with age and diet as between-groups factors. Antioxidant enzyme and O2 •− generation data were evaluated by one-way analyses. Data from the diet crossover (reversibility) experiments were subjected to two-way analyses with long-term diet and short-term diet as between-groups factors. Planned individual comparisons between age and diet groups were performed by single degree of freedom F tests using the error term from the overall analysis.

RESULTS

Effect of age and caloric intake on oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins and lipids

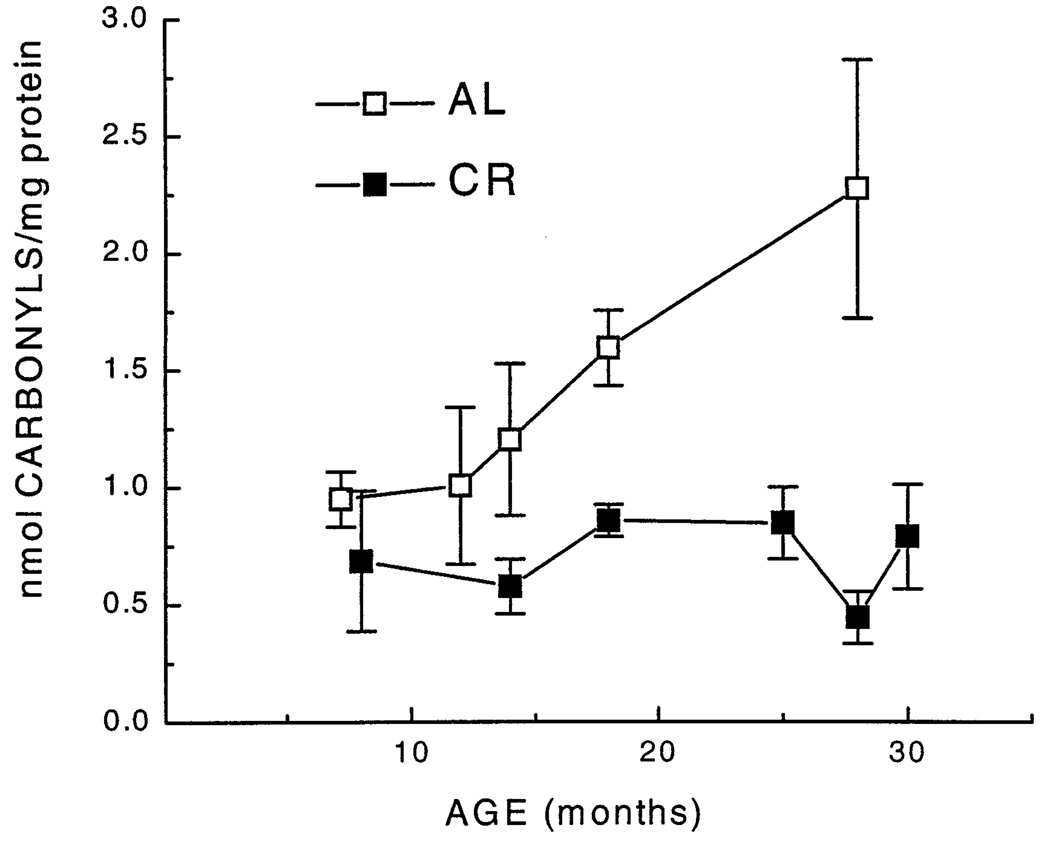

Measurements were made on the homogenates of mitochondria, isolated from upper hindlimb skeletal muscles of mice, ranging from 3 to 31 months of age. Protein oxidative damage was measured by HPLC as an increase in the concentration of protein carbonyls and a loss in protein sulfhydryl content, while lipid peroxidation was quantified by the concentration of TBARS. Mitochondrial carbonyl content in the AL mice, measured from 7 to 29 months of age, remained at relatively the same level between 6 and 12 months of age, but increased steadily thereafter by ~150% at 29-months of age (Fig. 1). In contrast, during a comparable range of age, mitochondria from the CR mice exhibited no discernable increase in carbonyl content (Fig. 1). In a separate, but relevant study conducted for a different purpose, carbonyl content of the homogenates of mouse hindlimb skeletal muscles, determined spectrophometrically, was found to increase by 32% between 4 and 30 months of age. (4 months, 1.15 ± 0.07 nmol/mg protein; 30 months, 1.68 ± 0.09 nmol/mg protein; mean ± SEM).

Fig. 1.

Carbonyl content of skeletal muscle mitochondria, determined by HPLC, as a function of age and dietary regime. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of measurements of 4–9 different mice. Data for carbonyl content of those age groups for which age-matched AL and CR groups were available were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance. This analysis suggested a main effect of diet [F(1,35) = 10.0, p = .003], but failed to yield an interaction of age and diet [F(3,35) = 1.9, p = .14]. Planned individual comparisons of age groups within each diet condition indicated a significant increase with age by 28 months for AL groups (p = .007), but failed to suggest increases for the CR groups.

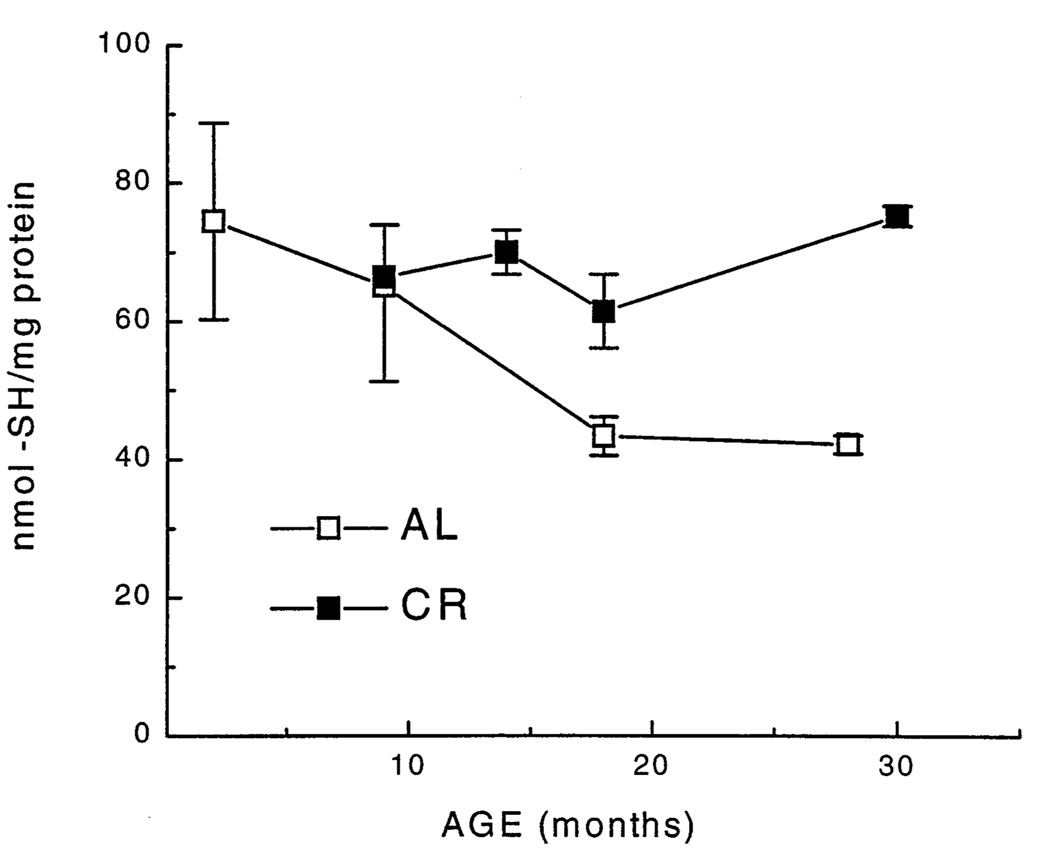

Mitochondrial protein sulfhydryl content in the AL mice decreased steadily by about 50% between 3 and 18 months of age, but remained unaltered thereafter, whereas, no demonstrable age-associated loss occurred in the CR mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Protein sulfhydryl content of skeletal muscle mitochondria determined by HPLC as a function of age and dietary regime. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of measurements of 2–6 different mice. Data for mitochondrial protein sulfhydryl content of those age groups for which age-matched AL and CR groups were available (9, 18, and 27–30 months) were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance. The analysis indicated a significant effect of diet [F(1,19) = 13.8, p = .001], and an interaction of diet with age that approached significance [F(2,19) = 3.5, p = .05]. Planned individual comparisons verified that 30-month-old CR groups did not differ from 9-month-old CR, whereas 18- and 27-month-old AL groups had significantly lower sulfhydryl concentrations when compared with the 9-month-old AL group (p < .023).

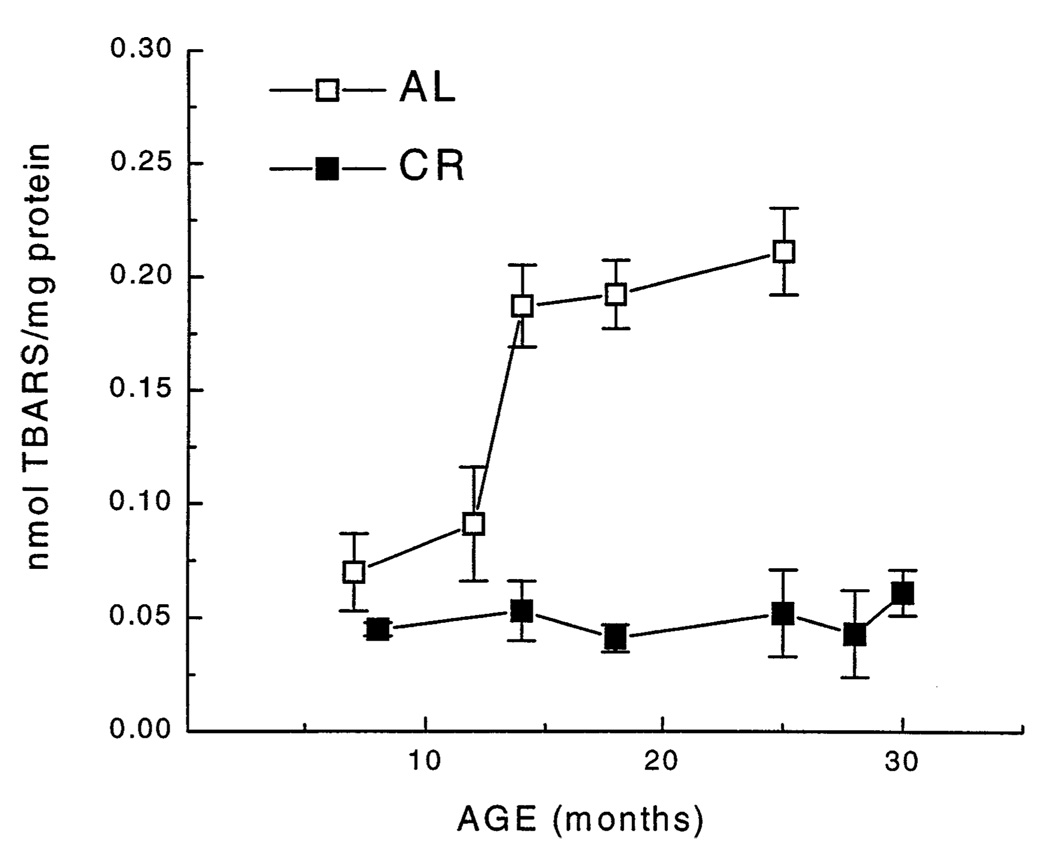

The concentration of TBARS in the mitochondrial homogenates from the AL mice showed a sigmoid increase with age (Fig. 3). The rapid increase (~2.5-fold) was observed between 12 and 14 months of age with no additional elevation thereafter. In sharp contrast, the concentration of TBARS in mitochondria from the CR group remained virtually unaltered during a comparable period of the life span (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Concentration of TBARS in skeletal muscle mitochondria as a function of age and dietary regime. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of measurements of 4–8 different mice. Data for TBARS of those age groups for which age-matched AL and CR groups were available were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance. The analysis revealed a significant interaction of age and diet [F(3,35) = 7.1, p = .001], as well as significant main effects of each of those factors (p < .001). Individual comparisons indicated that the 14-, 18-, and 24-month-old AL groups differed significantly from the 7-month-old AL group (p < .001), whereas no age differences were evident among the CR groups.

Effect of age and caloric intake on mitochondrial O2 •− generation

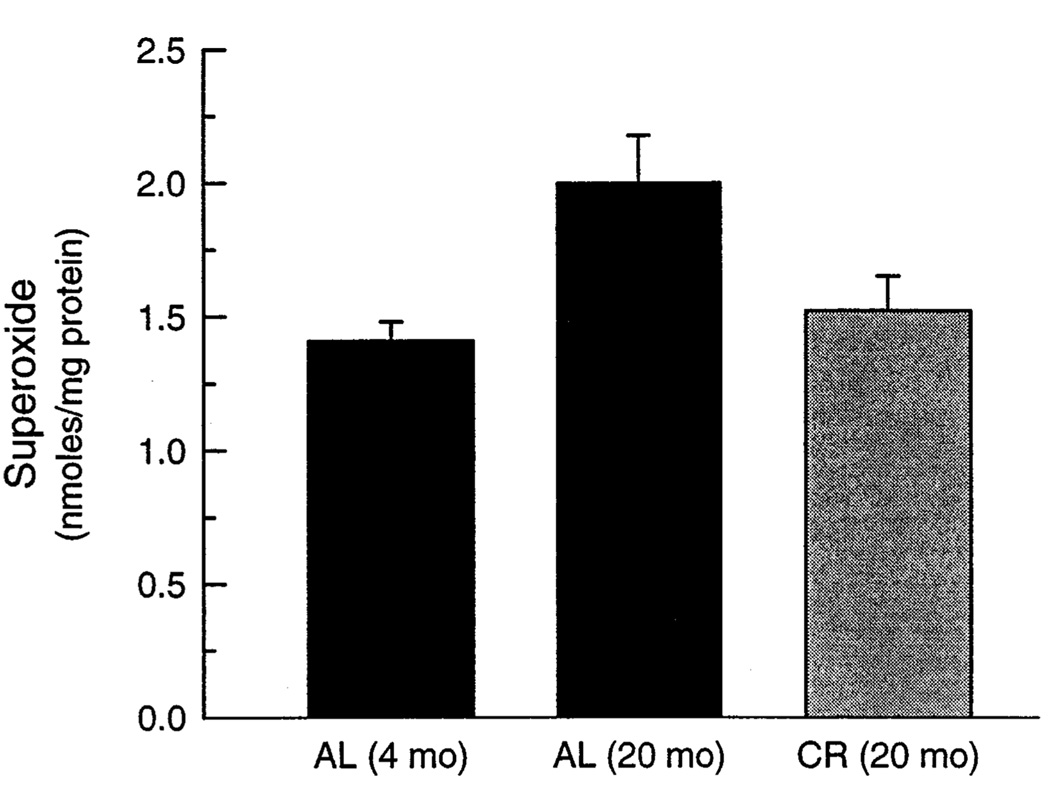

To understand the potential cause(s) of the age-related increase in mitochondrial oxidative damage, rates of mitochondrial O2 •− generation were compared between young (4-month-old) and relatively old (20-month-old) AL and CR mice. It should be noted that age-related increase in protein and lipid oxidative damage had already occurred by the latter age (see Fig. 1–Fig. 3). The rate of O2 •− generation, measured in the submitochondrial particles (SMPs), was 41% higher in the 20-month-old AL mice as compared to the 4-month-old AL mice, however, no significant differences were observed between the 20 month-old CR and 4 month-old AL mice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Rate of O2 •− generation in submitochondrial particles in young (4 months) and aged mice (20 months) reared under AL or CR feeding regimens. O2 •− generation was measured as SOD-inhibitable reduction of acetylated cytochrome c. Each value is the mean ± SEM of measurements of 5 different mice. A one-way analysis of variance for the three groups indicated a significant main effect (p < .05); planned individual comparisons of 20-month-old AL and CR groups with the 4-month-old controls indicated significant effects for AL (p < .05) but not CR groups.

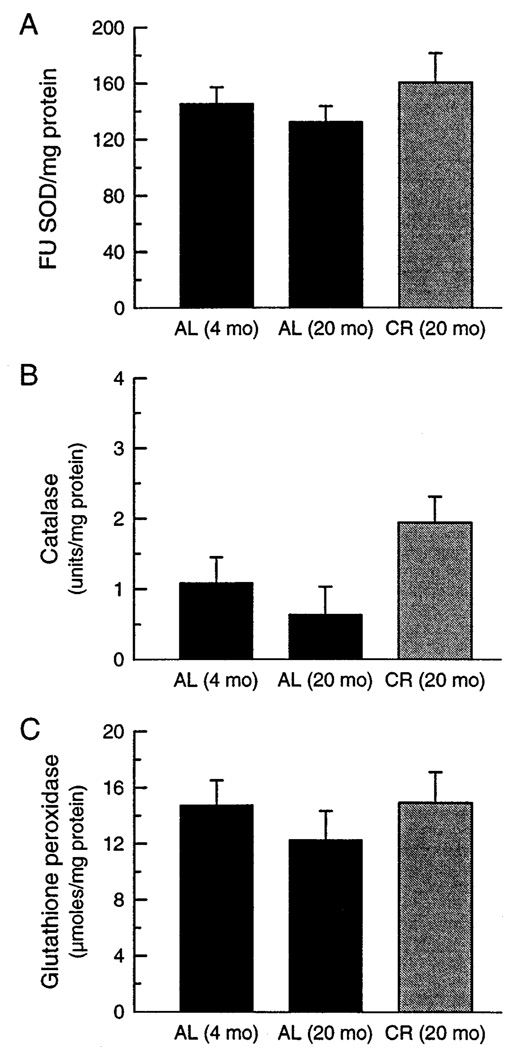

Effect of age and caloric intake on antioxidative enzymatic defenses

To determine if a potential decline in antioxidative defenses could be a contributory causal factor in the age-related increase in mitochondrial oxidative damage, activities of total SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase were measured in the homogenates of the skeletal muscles from 4- and 24-month-old mice (Fig. 5). No statistically significant differences in the activities of these three enzymes were detectable between the 4- and 24-month-old AL mice. Catalase activity was, however, significantly higher in the 24-month-old CR mice than in AL mice of the same age. It is, however, worth emphasizing that catalase activity in the skeletal muscle is relatively low when compared to other tissues (e.g., 0.6% of that in the kidney) and verges on the limit of reliable detectability.

Fig. 5.

Activities of antioxidantive enzymes as a function of age and diet: (A) SOD (FU/mg protein), (B) catalase (units/mg protein), and (C) glutathione peroxidase (µmoles/mg protein) were measured in skeletal muscle homogenates. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of determinations of 6–8 different mice. Analyses of variance failed to reveal significant overall effects for each of the enzymes except for catalase (p < .05). Planned individual comparisons indicated that catalase activity of the 20-month-old CR group differed significantly from that of the 4-month-old AL group (p < .05).

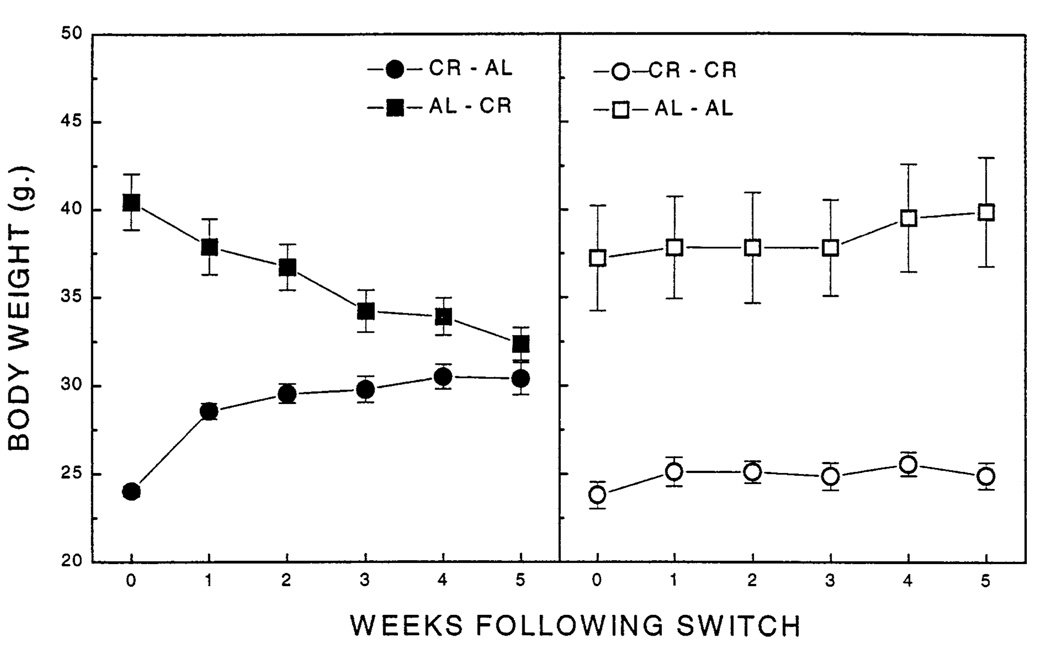

Reversibility of mitochondrial oxidative damage related to caloric intake

A separate study was conducted to determine the extent to which differences in mitochondrial oxidative damage between the AL and the CR group could be attributed to a reversible effect of the feeding regimen, as opposed to a relatively permanent retardation of age-associated changes. Relatively old mice were used in the reversibility studies in order to ensure that significant differences would be detected between the AL and CR mice on the measures of carbonyls, sulfhydryls, and TBARS (see Fig. 1–Fig. 3). Sensitivity of oxidative damage to the dietary regimen was determined in groups of 19.5-to 23.5-month-old AL and CR mice that had been switched to the opposite dietary regimen for a period of 42 d prior to the removal of skeletal muscle tissue. The effects of these dietary switches (AL→CR and CR→AL) on body weight and oxidative damage are shown in comparison to the age-matched, non-switched controls (AL→AL and CR→CR) in Fig. 6. Body weights of the CR→AL group showed an increase primarily during the first week following the introduction of the AL regimen, with little additional weight gain between weeks 3 to 5. In contrast, the AL→CR groups showed steady weight loss across the 5 weeks following the introduction of CR. Neither of the switched groups attained weights approaching those of control groups kept constantly on one dietary regimen, an effect which we have observed in previous studies [25]. The fact that the mice tend to stabilize at intermediate body weights following changes in diet suggests that there must be persistent metabolic or behavioral adaptations to the life-long AL and CR regimes.

Fig. 6.

Body weight adjustment over a 5-week period following changes in feeding regimen. The left panel shows switched groups (AL→CR and CR→AL) whereas the right panel shows unswitched controls (AL→AL; CR→CR). Each value represents the mean body weight (g ± SEM) of 5–7 different mice. A three-way repeated measures analysis of variance conducted on body weights of mice in the reversibility experiments revealed significant main effects of long-term diet, short-term diet, and time, as well as a three-way interaction of those factors (all p < .01).

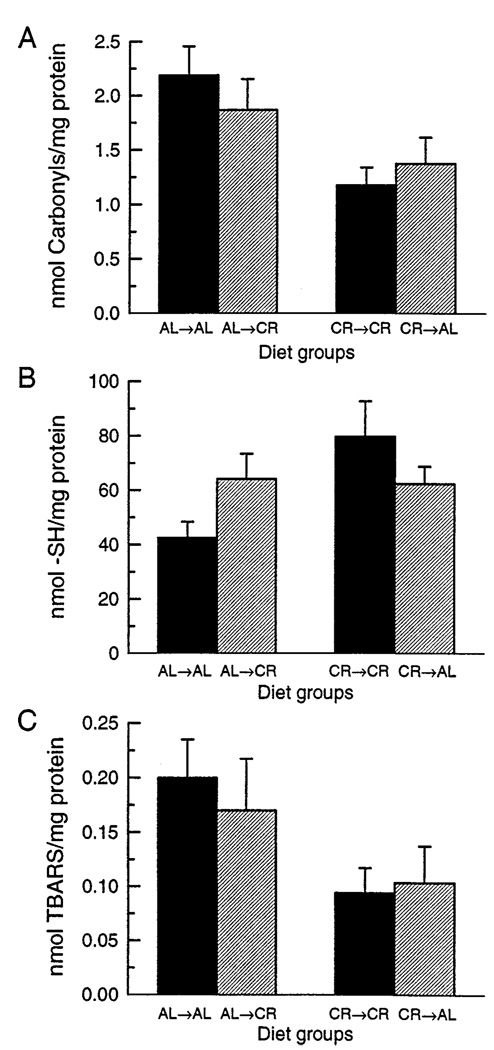

Comparisons of the amounts of protein carbonyls, protein sulfhydryl content, and concentration of TBARS between switched and nonswitched groups indicated similar patterns of change (Fig. 7). In each case, switching to the opposite dietary condition resulted only in a slight reversal. For example, AL mice switched to the CR condition had somewhat lower carbonyl content when compared with the AL→AL groups, while CR mice switched to AL had slightly higher amounts of carbonyls when compared with the CR→CR group (Fig. 7A). Loss of protein sulfhydryls (Fig. 7B), and concentrations of TBARS (Fig. 7C) followed a pattern similar to the protein carbonyls. Whereas comparison between the AL→AL group and the CR→CR group yielded significant effects for each measure (all p < .05), none of the switched groups differed significantly from their nonswitched controls (i.e., AL→AL vs. AL→CR; CR→CR vs. CR→AL). The largest difference attributable to diet switch, which occurred between the AL→CR and AL→AL groups for protein sulfhydryls (Fig. 7B), was not statistically reliable (p = .11).

Fig. 7.

Measures of oxidative damage in skeletal muscle mitochondria following changes in feeding regimens of mice previously maintained under long-term AL or CR conditions: (A) carbonyl content determined by HPLC; (B) protein sulfhydryl content determined by HPLC; (C) TBARS. All values are expressed as nmol/mg protein ± SEM (n = 6) for each of the four diet groups. Two-way analyses of variance performed on each measure indicated a significant overall effect of long-term diet regimen (p < .05) but indicated neither a main effect of short-term diet regimen nor an interaction of long and short-term diet regime (all p > .06). Individual comparisons between the groups also failed to indicate significant differences between switched and nonswitched groups (i.e., AL→AL vs. AL→CR and CR→CR vs. CR→AL). All comparisons of AL→AL and CR→CR groups yielded significant effects (all p < .05).

DISCUSSION

Results of this study demonstrate that mitochondria in the hindlimb skeletal muscles of the mouse undergo a significant age-related increase in oxidative damage to proteins and lipids; additionally, the accrued damage, although largely irreversible, can be prevented by reducing caloric intake. An age-related increase in the amounts of protein carbonyls has been reported in homogenates of various tissues from mammals [5,11] and of whole insects [33]. However, the issue of whether different cellular organelles or compartments accumulate different amounts of protein carbonyls or other types of oxidative damage, during aging has, as yet, not been well addressed. Results of this study may provide a tentative indication. For instance, the carbonyl content of the homogenates of whole hindlimb skeletal muscles, measured spectrophotometrically, was 32% higher in the 30-month-old AL mice than in the 4-month-old AL mice, whereas the age-related increase (7 to 29 months) in the carbonyl content of the mitochondrial fraction, determined by HPLC, was 150%. Although the absolute values of the carbonyl content measured by the two different methods may not be directly comparable, nevertheless, the greater percentage increase in carbonyl content in mitochondria than in the muscle homogenates suggests that during aging mitochondrial proteins become relatively more oxidized than those of the whole muscle.

This inference accords with the predictions of a variety of previous studies demonstrating that mitochondria are not only the main producers of ROS, a process that would tend to result in the infliction of oxidative damage to them, but that the rate of mitochondrial O2 •−/H2O2 generation apparently increases during aging in several tissues and species (reviewed in [6]). Results of this study, therefore, provide yet another example of the increase in mitochondrial O2 •− generation during aging. Such an increase in O2 •− generation, and by extension of other ROS derived from it, may be a causal factor in the age-related increase in mitochondrial oxidative damage. This view is bolstered by the present observation that activities of antioxidative enzymes SOD, catalase, or glutathione peroxidase do not decline during aging. However, increases in the activities of these antioxidative enzymes have been reported in rat skeletal muscle with age and attenuated by CR (reviewed in [22]). Another possible reason for the age-related increase in mitochondrial oxidative damage, which was not examined in this study, may be that autophagic and/or protease and/or lipase activities may decline during aging. Whatever the underlying cause(s) may be, the physiological implication is that mitochondria undergo significant oxidative damage during aging, which may deleteriously affect their respiratory function. Indeed, studies indicate that oxidative damage to mitochondria can cause loss of activity of specific enzymes, e.g., aconitase, a citric acid cycle enzyme [34].

It seems rather remarkable that a 40% reduction in caloric intake prevents the age-associated increases in mitochondrial protein and lipid oxidative damage. The mechanism for such protection may be the lowering of the rates of mitochondrial O2 •− generation in the CR animals, as observed here and previously [11]. Another hypothetical possibility, raised in the literature [35], is that CR induces an increase in the activities of antioxidative enzymes, particularly catalase, which results in a decrease in oxidative damage. While improved antioxidative defenses might be effective in decreasing the amounts of oxidative damage, the results of this study do not support the view that induction of antioxidative enzyme activity is a likely factor in the skeletal muscles. First, there were no significant differences in the activities of skeletal muscle SOD and glutathione peroxidase between the AL and CR animals. Second, although skeletal muscle catalase activity was greater in the CR than in the AL mice, the level of catalase activity itself is extremely low (for instance, 0.6% of that in the kidney), which argues against the interpretation that enhancement of catalase activity may be the main factor for preventing the age-associated increase in mitochondrial oxidative damage. Nevertheless, this possibility cannot be completely ruled out. Another possibility is that the efficiency of processes removing oxidative damage may vary between the CR and AL mice.

One of the major questions pertaining to the life-extension effects of CR is whether or not this regimen indeed operates by slowing down the aging process. For example, Richardson and McCarter [36] have theorized that mechanism(s) underlying the life-extension effects of CR may operate via two alternate models. One model postulates that CR extends life span by elevating the “set-point” of the efficiency of the putative physiological factors affecting the life span. Previous investigation of protein oxidation in brain homogenates of C57BL/6 mice suggested a pattern consistent with the hypothesis that the CR regimen could induce a condition of elevated efficiency of cellular processes by virtue of lowering the steady-state level of oxidative stress/damage, without necessarily retarding the progressive accumulation of oxidative damage associated with aging processes [25]. When introduced in 15-month-old AL mice, the CR regimen was sufficient to produce a relatively rapid reduction in the level of protein oxidation and, conversely, introduction of AL feeding in CR mice resulted in a return to ad libitum levels of protein oxidation. Results of the present study contrast sharply with those demonstrated for brain homogenates, in that the steady-state amounts of oxidative damage to mitochondria in aged CR and AL animals fail to show substantial change up to 6 weeks following the switches in the dietary regimen from CR to AL, and vice versa. The apparent irreversibility of mitochondrial protein and lipid oxidative damage is compatible with assumptions of the second model termed the ‘rate’ model, which suggests that CR prolongs life span by reducing the rate of the primary aging process(es). If this interpretation were indeed true, it would imply that CR decreases the rate of ROS generation, thereby attenuating the age-related accrual of oxidative damage, which, in turn, retards the loss of physiological functions, resulting in the extension of life span.

In conclusion, results of the present study suggest that mitochondrial oxidative damage is closely linked to the aging process, and they support the concept that life-span extension by CR may operate via lowering the level of oxidative stress and retarding the accumulation of mitochondrial damage.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the grant RO1 AG13563 from National Institutes of Health-National Institute on Aging.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AL

ad libitum

- CR

caloric restriction

- DNPH

2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine

- DTNB

5,5-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- O2•−

superoxide anion radicals

- SMPs

submitochondrial particles

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TBARS

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- UNTHSC

University of North Texas Health Science Center

REFERENCES

- 1.McCarter RJ. Age-related changes in skeletal muscle function. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1990;2:27–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03323892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeli E, Reznick AZ. The physiology and biochemistry of skeletal muscle atrophy as a function of age. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1994;206:103–113. doi: 10.3181/00379727-206-43727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WJ. What is sarcopenia? J. Gerontol. 1995;50A:5–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Geront. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992;257:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1355616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nohl H, Hegner D. Do mitochondria produce oxygen radicals in vivo? Eur. J. Biochem. 1978;82:563–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohal RS, Dubey A. Mitochondrial oxidative damage, hydrogen peroxide release, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1994;16:621–626. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohal RS, Ku HH, Agarwal S, Forster MJ, Lal H. Oxidative damage, mitochondrial oxidant generation and antioxidant defenses during aging and in response to food restriction in the mouse. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1994;74:121–133. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohal RS, Agarwal S, Candas M, Forster MJ, Lal H. Effect of age and caloric restriction on DNA oxidative damage in different tissues of C57BL/6 mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1994;76:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)91595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S, Sohal RS. DNA oxidative damage and life expectancy in houseflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:12332–12335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sohal RS, Sohal BH. Hydrogen peroxide release by mitochondria increases during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1991;57:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90034-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ku HH, Brunk UT, Sohal RS. Relationship between mitochondrial superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production and longevity of mammalian species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1993;15:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90165-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohal RS, Sohal BH, Orr WC. Mitochondrial superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation, protein oxidative damage, and longevity in different species of flies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;19:499–504. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu YJD, Richardson A. Effect of age on the function of mitochondria isolated from brain and heart tissue. Exp. Geront. 1980;15:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darnold JR, Vorbeck ML, Martin AP. Effect of aging on the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1990;53:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90067-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weindruch R, Walford RL, editors. The retardation of aging and disease by dietary restriction. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masoro EJ. Dietary restriction and aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1993;41:994–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingram DK, Weindruch R, Spangler EL, Freeman JR, Walford RL. Dietary restriction benefits learning and motor performance of aged mice. J. Gerontol. 1987;42:78–81. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weindruch R. Interventions based on the possibility that oxidative stress contributes to sarcopenia. J. Geront. 1995;50A:157–161. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson A. Changes in the expression of genes involved in protecting cells against stress and free radicals. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1991;3:403–405. doi: 10.1007/BF03324050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackwell BN, Bucci TJ, Hart RW, Turturro A. Longevity, body weight, and neoplasia in ad libitum-fed and diet-restricted C57BL6 mice fed NIH-31 open formula diet. Toxicol. Pathol. 1995;23:570–582. doi: 10.1177/019262339502300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubey A, Forster MJ, Lal H, Sohal RS. Effect of age and caloric intake on protein oxidation in different brain regions and on behavioral functions of the mouse. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;333:189–197. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong SHY, Knight JA, Hopfer SM, Zaharia O, Leach CN, Sunderman FW. Lipoperoxides in plasma as measured by liquid-chromatographic separartion of malondialdehyde-thiobarbituric acid adduct. Clin. Chem. 1987;33:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shacter E, Williams JA, Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Determination of carbonyl groups in oxidized proteins. In: Pun-chard NA, Kelly FJ, editors. Free radicals, a practical approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1996. pp. 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernster L, Dallner G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1271:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitz DR, Oberley LW. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian homogenates. Analyt. Biochem. 1989;179:8–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luck H. Catalase. In: Bergmeyer H, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 885–894. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beutler E. Glutathion peroxidase. In: Beutler E, editor. Red cell metabolism, a manual of biochemical methods. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1971. pp. 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohal RS, Agarwal S, Dubey A, Orr WC. Protein oxidative damage is associated with life expectancy of houseflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:7255–7259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan LJ, Levine RL, Sohal RS. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11168–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu BP. Aging and oxidative stress: modulation by dietary restriction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;21:651–668. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson A, McCarter R. Mechanism of food restriction: change in rate or change of set point? In: Ingram DK, Baker GT III, Shock NW, editors. The potential for nutrient modulation of aging process. Trumbull, CT: Food and Nutrition Press; 1991. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]