Abstract

Background

Despite new opportunities to expand buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence, use of this treatment modality has been limited. Physicians may question their ability to successfully treat opioid-dependent patients with buprenorphine in a primary care setting. We describe a buprenorphine treatment program and treatment outcomes in an urban community health center.

Methods

We conducted retrospective chart reviews on the first 41 opioid-dependent patients treated with buprenorphine/naloxone. The primary outcome was 90-day retention in treatment.

Results

Patients’ mean age was 46 years, 70.7% were male, 58.8% Hispanic, 31.7% black, 57.5% unemployed, and 70.0% used heroin prior to treatment. Twenty-nine (70.7%) patients were retained in treatment at day 90. Compared to those not retained, patients retained in treatment were more likely to have used street methadone (0% versus 37.9%) and less likely to have used opioid analgesics (54.6% versus 20.7%) and alcohol (50.0% versus 13.8%) prior to treatment. Of the 25 patients with urine toxicology tests, 24% tested positive for opioids.

Conclusions

Buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence in an urban community health center resulted in a 90-day retention rate of 70.7%. Type of substance use prior to treatment appeared to be associated with retention. These findings can help guide program development.

In the United States, the rates of opioid abuse and dependence have increased over the last several years.1–3 However, until recently, treatment options for opioid dependence have been limited. Although maintenance pharmacotherapy with opioid agonists reduces adverse consequences of opioid dependency,4–10 fewer than 20% of opioid-dependent individuals are enrolled in substance abuse treatment programs.11,12 Recent legislation and the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of buprenorphine (an oral long-acting partial opioid agonist) for treatment of opioid dependence have broadened treatment options for opioid-dependent patients. Physicians who obtain waivers to prescribe buprenorphine to treat opioid dependence can now prescribe buprenophrine outside of restrictive substance abuse treatment settings.

Despite this new treatment opportunity, prescription of buprenorphine by primary care clinicians has been limited.13,14 One potential reason for this limited use slow uptake may be physicians’ caution in adopting a new treatment paradigm with drug users. Few studies have been published that describe the use of buprenorphine for treating opioid dependence outside of substance abuse treatment settings or clinical trials (with strict eligibility criteria and time-intensive treatment protocols). As such, physicians may question their ability to devote sufficient time to treating substance users and be skeptical about the potential for buprenoprhine treatment to be successful. Thus, resources that can help physicians and health care administrators understand how bupreorphine treatment can be integrated into primary care settings without strict eligibility criteria or time-intensive protocols can be helpful in planning and guiding buprenorphine treatment in primary care settings.

In this report, we describe treating opioid-dependent patients with buprenorhine in a community health center in the Bronx, NY. Specifically, we describe the buprenorphine treatment program and treatment outcomes.

Methods

The Buprenorphine Treatment Program

Setting

Buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence was initiated in a federally qualified community health center in the South Bronx. The neighborhood in which the health center is located is one of the poorest in New York City, with 32%–46% of individuals living below the poverty line.15 Additionally, in this neighborhood, deaths and hospitalizations from drug use and HIV are among the highest in New York City.16 Of the 15,000 patients at the community health center, the majority are female and black or Hispanic. The study was approved by the Montefiore Medical Center institutional review board.

Patients

Adult patients who presented to the health center between November 2004 and January 2007 with opioid dependence (as defined by DSM-IV criteria17) were considered candidates for treatment with buprenorphine and are included in this report. Patients from within and outside of the health center were identified by health care providers, referred from outside organizations, or self-identified. Self-referred patients may have been informed about our program through word of mouth, Internet sites that provide information about buprenorphine treatment providers, or flyers/brochures placed in the community. In accordance with the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) Guidelines,18 patients with certain conditions were considered to not be appropriate for buprenorphine treatment at the health center and were referred to a substance abuse treatment center. These conditions included (1) pregnancy, (2) alcohol dependency as defined by DSM-IV criteria, (3) benzodiazepine dependency as defined by DSM-IV criteria, (4) serum transaminase levels more than five times the upper limit of normal, (5) current suicidal ideation, and (6) taking more than 30 mg of methadone daily in a methadone maintenance program in the past 30 days. In November 2006, the last criterion was changed to taking more than 60 mg of methadone daily in a methadone program in the past 14 days.

Staffing

Four general internists worked closely with a clinical pharmacist to screen, assess, induce, and maintain patients with buprenorphine treatment. Each general internist was available in the health center on a part-time basis, each providing care for 1–4 half days per week. The clinical pharmacist was available 4 half days per week. Physicians were supported by routine patient care/billing, while the pharmacist was partially supported by a grant. Although one social worker was available for all health center patients, there were no on-site support groups or substance abuse counselors. Limited psychiatric and mental health counseling services were available; however, because these services were funded by the Ryan White CARE Act, they were only offered to HIV-infected patients.

Initial Visit

In the initial visit prior to starting buprenorphine treatment, patients were educated about buprenorphine/naloxone, standardized substance abuse histories were taken, and laboratory tests were obtained. The substance abuse history included questions about onset of drug use, heaviest drug use, route of drug use, and amount and frequency of drug use in the previous 30 days for heroin, opioid analgesics, “street” methadone, prescribed methadone, benzodiazepines, crack/ cocaine, marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs if applicable. Patients were asked about current and previous drug treatment, mental health diagnoses and treatment, and social indicators. Laboratory tests included liver function tests, a urine toxicology test, and a urine pregnancy test if applicable. Eligible patients were scheduled for induction with buprenorphine/naloxone within 1–2 days after the initial visit.

Buprenorphine Induction and Stabilization

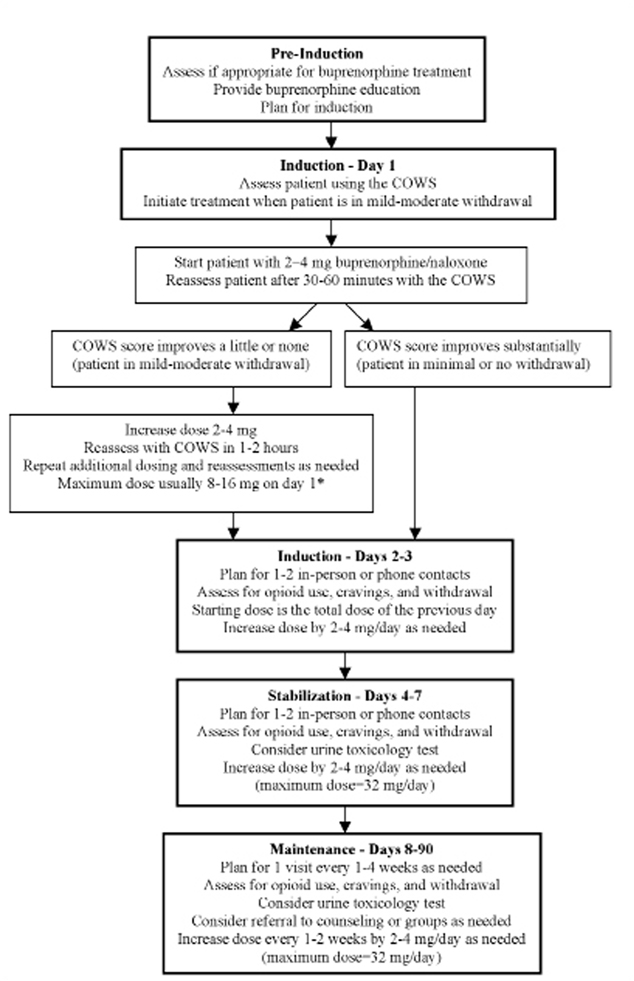

Buprenorphine induction and stabilization occurred through a joint effort between the physicians and pharmacist. Providers monitored signs of opioid withdrawal using a standardized clinical tool (the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale19 and adjusted buprenorphine/naloxone doses accordingly (Figure 1). Because of our team approach, visits and phone calls occurred with the physician only, the pharmacist only, or both providers. Explicit counseling sessions were not offered at our health center, but psychosocial counseling techniques (eg, motivational interviewing) were often incorporated into medical visits. During the induction and stabilization process, buprenorphine/naloxone was provided on-site by the pharmacist, who dispensed enough medication until the following visit. Patients were provided the physician’s and pharmacist’s after-hours contact information to facilitate ongoing communication during the induction and stabilization process. The induction period typically occurred on days 1–3 (day 1 represents the first day on which buprenorphine/naloxone was taken), with patients reaching a stable dose of buprenorphine/naloxone on days 4–7.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Buprenorphine Program

COWS—Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale19

* Buprenorphine Consensus Statement and unpublished data from VA/NIDA #1018 trial indicates that a first day dose of up to 16 mg can be administered.

For comprehensive guidelines on buprenorphine treatment, see: Center for Susstance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opoid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. Available at http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Bup%20Guidelines.pdf.

Buprenorphine Maintenance

Once patients’ doses were stable, the frequency of their contacts with the physician and pharmacist decreased. The use of urine toxicology tests varied between physicians and was guided by clinical judgment. Buprenorphine treatment was never terminated because of results of urine toxicology tests. Early in the program, all maintenance doses of buprenorphine/naloxone were dispensed by our pharmacist, but after physicians became more comfortable with buprenorphine treatment, they referred patients to community pharmacies to obtain prescriptions. We considered treatment success to be retention in buprenorphine treatment at day 90 as confirmed by medical records.

Data

We conducted retrospective chart reviews extracting demographic and clinical information on patients who received at least one dose of buprenorphine/ naloxone between November 2004 and January 2007 at our community health center. Data were extracted from standardized substance abuse history forms, clinic visits, and laboratory tests. Because of our small sample size, we present frequencies of our variables and make inferences based on observed trends rather than relying on formal statistical significance testing.

Results

Over the study period, 74 people inquired about buprenorphine treatment. Four people were ineligible—one was not opioid dependent, one was taking >30 mg of methadone (prior to November 2006), and two were taking >60mg of methadone (after November 2006). Twenty-nine eligible patients never returned for a full assessment or buprenorphine induction. The remaining 41 patients took at least one dose of buprenorphine/naloxone and are included in this report.

The mean age of the patients was 46 years, and the majority of the patients were male (70.7%), Hispanic (58.8%) or black (31.7%), unemployed (57.5%), and had public health insurance (78.1%) (Table 1). The most common referral source for patients was providers within our community health center (29.3%), followed by a nearby community-based organization/syringe exchange program (19.5%), other sites within our affiliated academic medical center (17.1%), and self-referral (17.1%).

Table 1.

Baseline and Treatment Characteristics of 41 Patients in the Buprenorphine Treatment Program

| Baseline Characteristics | Total n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 46.4 ± 8.7 |

| Male | 29 (70.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 24 (58.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13 (31.7) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 4 (9.8) |

| Insurance | |

| Public insurance | 32 (78.1) |

| Private insurance | 8 (19.5) |

| None | 1 (2.4) |

| Employed | 17 (42.5) |

| Referral source | |

| Community health center | 12 (29.3) |

| Community-based organization | 8 (19.5) |

| Affiliated academic health center | 7 (17.1) |

| Self | 7 (17.1) |

| Methadone maintenance program | 4 (9.8) |

| Other | 3 (7.3) |

| Substance use* | |

| Heroin | 28 (70.0) |

| Opioid analgesics | 12 (30.0) |

| Prescribed methadone | 11 (27.5) |

| “Street” methadone | 11 (29.0) |

| Crack/cocaine | 17 (42.5) |

| Any alcohol | 9 (23.1) |

| Ever injected drugs | 22 (56.4) |

| HIV infection | 13 (31.7) |

| Hepatitis C Virus antibody positive | 21 (52.5) |

| Buprenorphine Treatment | |

| Median number of visits | |

| Induction and stabilization (days 1–7) | 3 (range=1–5) |

| Maintenance (days 8–90) | 6 (range=0–17) |

| Median buprenorphine/naloxone dose | |

| Induction (day 1) | 8 mg (range=2–18 mg) |

| Stabilization (day 7) | 10 mg (range=2–32 mg) |

| Maintenance† (day 90) | 12 mg (range=1–32 mg) |

| Retained in treatment at day 90 | 29 (70.7) |

| Urine toxicology test performed | 25 (61.0) |

| Positive for opioids | 6 (24.0) |

| Positive for any drug‡ | 16 (64.0) |

Because of a few missing data points for some variables, denominators reflect the number of valid responses.

Self-reported substance use 30 days prior to initiation of buprenorphine treatment

If patients were not in treatment at 90 days, then the last known dose after day 7 was recorded.

Drugs tested included opioids, cocaine, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and phencyclidine.

The majority of patients (70.0%) reported using heroin within 30 days prior to their initial visit. Other opioids used within 30 days prior to treatment included prescribed and street opioid analgesics (30.0%), street methadone (29.9%), and prescribed methadone (27.5%). Other substances used prior to treatment included crack/cocaine (42.5%) and any alcohol (23.1%). The majority of patients had a history of injection drug use (56.4%) and positive antibodies to hepatitis C virus (52.5%). Thirteen (31.7%) were infected with HIV.

Of the 41 patients who took at least one dose of buprenorphine/naloxone, 29 (70.7%) were induced at our community health center, and 12 were induced elsewhere (eg, in a hospital or drug treatment program). Of those induced in our health center, the median number of visits during the induction and stabilization period (days 1–7) was three visits. For all patients, the median number of visits during the maintenance period (days 8–90) was six visits.

The dosing of buprenorphine varied among patients. In general, however, the majority of patients required doses that were in the middle range of approved doses (maximum buprenorphine/naloxone dose recommended is 32 mg/day). On day 1 of induction the median buprenorphine/naloxone dose was 8 mg, with 73.2% of patients receiving a dose between 4–8 mg. On day 7 after stabilization, the median dose was 10 mg, with 63.2% of patients receiving a dose between 8–16 mg. On day 90 (or last day of treatment if not retained), the median dose was 12 mg, with 68.6% of patients receiving a dose between 8–16 mg.

Twenty-nine (70.7%) patients were retained in treatment at day 90. Twenty-five (61.0%) patients had at least one urine toxicology test performed after starting buprenorphine treatment. Physicians’ practices varied with regard to urine toxicology tests: one tested 100% of patients, one tested 75.0%, one tested 41.2%, and one tested no patients (but had treated only one patient). Of these 25 patients with tests, most had two or more tests, with tests occurring at various intervals ranging from day 2 to day 90. Of those with tests, 24% had at least one test positive for opioids, and 64% had at least one test positive for any drug (opioids, cocaine, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, phencyclidine). The most common drugs present in positive tests were cocaine (32.0%) and cannabinoids (28.0%).

Compared to those not retained, patients retained in treatment were more likely to have used street methadone (0% versus 37.9%, P<.05) and less likely to have used opioid analgesics (54.6% versus 20.7%, P<.05) and alcohol (50.0% versus 13.8%, P<.05) prior to treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline and Treatment Characteristics of 41 Patients Not Retained and Retained in Buprenorphine Treatment

| Baseline Characteristics | Not Retained in Buprenorphine Treatment (n=12) n (%) |

Retained in Buprenorphine Treatment (n=29) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 9 (75.0) | 20 (69.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6 (50.0) | 18 (62.1) |

| Employed | 2 (18.2) | 15 (51.7) |

| Substance use* | ||

| Heroin | 9 (81.8) | 19 (65.5) |

| Opioid analgesics | 6 (54.6) | 6 (20.7) † |

| Prescribed methadone | 3 (27.3) | 8 (27.6) |

| “Street” methadone | 0 (0) | 11 (37.9) † |

| Crack/cocaine | 6 (54.6) | 11 (37.9) |

| Any alcohol | 5 (50.0) | 4 (13.8) † |

| Ever injected drugs | 6 (60.0) | 16 (55.2) |

| HIV infection | 6 (50.0) | 7 (24.1) |

| Buprenorphine treatment | ||

| Median buprenorphine/naloxone dose | ||

| Induction (day 1) | 8 mg | 8 mg |

| Stabilization (day 7) | 10 mg | 9 mg |

| Maintenance‡ (day 90) | 12 mg | 12 mg |

| Urine toxicology tests performed | 5 (41.7) | 20 (69.0) |

| Positive for opioids | 1 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) |

| Positive for any drug§ | 4 (80.0) | 12 (60.0) |

All percentages signify column percentages. Because of a few missing data points for some variables, denominators reflect the number of valid responses.

Self-reported substance use 30 days prior to initiation of buprenorphine treatment

P<.05

If patients were not in treatment at 90 days, then the last known dose after day 7 was recorded

Drugs tested included opioids, cocaine, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and phencyclidine.

Discussion

In an urban community health center, patients who sought treatment for opioid dependence with buprenorphine were predominantly male, from racial/ethnic minorities, and heroin users. Overall, the 90-day retention rate was 71%. Our data suggest that compared to those not retained in buprenorphine treatment, those retained may be more likely to have used street methadone and less likely to have used opioid analgesics and alcohol prior to starting treatment. Of those with urine toxicology tests, 24% had evidence of ongoing opioid use.

Our 90-day retention rate of 71% is comparable to that in rhe few primary care-based buprenorphine treatment programs previously described. Despite having patients with a higher socioeconomic status, one buprenorhpine program in Rhode Island reported a retention rate of 59% at 24 weeks.20 Another buprenorphine program treating homeless and primary care patients in Boston had retention rates of 77%–93% at 3 months, respectively.21 However, in that program patients had 16–28 contacts per person with the nurse case manager in the first month of treatment. Our retention rate is a bit lower than those reported in clinical trials conducted in primary care settings.22–24 These studies had strict eligibility criteria (eg, no cocaine use), on-site dispensing of buprenorphine up to thrice weekly, and required one–three weekly counseling sessions. Retention rates in these trials were 78%–81% at 10–13 weeks. These types of programs with strict eligibilty criteria and intense protocols may be difficult to implement in many primary care settings.

Our data suggest that retention rates may differ by type of substance use prior to initiating buprenorphine treatment. We found that retention rates were higher among those using street methadone and lower among those using opioid analgesics and any alcohol prior to starting buprenorphine. Based on our clinical experience, we hypothesize that patients who were buying street methadone may have been “self-treating” their opioid dependence. We believe this selftreatment signified the desire to reduce or stop illicit opioid use but without guidance of health care providers. These patients who self-treated with street methadone may have been more motivated than others to remain in a treatment program that was specifically not a methadone maintenance treatment program.

Our finding that individuals who used opioid analgesics prior to starting treatment were less likely to be retained in treatment conflicts with findings of a few other studies.24–26 In these studies, opioid analgesic users differed from heroin users in demographic characteristics and drug treatment histories. Opioid analgesic users may represent a different type of opioid-dependent patient than heroin users. In our clinical experience, many patients who take opioid analgesics do not view their use as problematic, even with DSM-IV diagnoses of opioid dependence.

Although alcohol dependence was an exclusion criterion, no patients were excluded for this reason. However, any alcohol use was associated with poor retention. With only nine patients who reported alcohol use, we were unable to separately analyze those with heavy, frequent, or binge drinking. Thus, alcohol use and its associated consequences should be further explored in research focusing on buprenorphine treatment.

Although urine toxicology tests were performed in only 61% of patients after starting buprenorphine treatment, 24% tested positive for opioids. However, 64% of those tested had evidence of other drug use, the most common being cocaine and cannibinoids. Of the 16 individuals without urine toxicology tests, nine were retained in treatment and seven were not. Clearly, we cannot be certain whether patients who did not have urine toxicology tests used drugs or not. If all 16 patients continued using opioids, then the proportion of patients with continued opioid use would be 54% (22 of 41) instead of 24% (6 of 25). Thus, in a worst-case scenerio, we would still consider buprenorphine treatment moderately successful.

Although not ideal for our evaluation, the lack of systematic collection of urine toxicology tests reflects patient care provided by different health care providers in the community. While obtaining urine toxicology tests is mandatory for methadone maintenance treatment, it is not required for buprenorphine treatment. Physicians’ decisions on whether to obtain urine toxicology tests is complex and beyond the scope of this discussion. Some may argue that ordering urine toxicology tests may undermine the patient-provider relationship due to confrontation and distrust. However, we believe that if handled in a sensitive way, obtaining urine toxicology tests can be one additional piece of important clinical information that can help improve patient-provider communication and patient care.

While the clinical goal for many patients is to eventually achieve abstinence from opioid addiction, providers treating opioid addiction in the primary care setting must recognize that reduction in opioid use should be considered a positive outcome, even if abstinence is not immediately achieved. In line with harm reduction principles, appropriate outcomes for many patients might include less opioid use, less injection drug use, less criminal activity, and more engagment with the health care system. Bringing opioid-dependent patients into primary care settings allows for more opportunities to treat or prevent associated chronic diseases such as HIV and/or hepatitis C virus infections. Further examation into the potential benefits of related outcomes of buprenorphine treatment in the primary care setting is warranted.

Limitations

There are limitations to our evaluation. Our sample size is small, which reflects the slow uptake of buprenorphine noted in previous studies.13,14 Because of this we were unable to fully examine factors associated with retention in treatment due to limited power. In addition, because our study was a retrospective chart review, we were unable to collect data that were not systematically recorded in medical records, which may be associated with treatment retention. Finally, similar to other buprenorhpine treatment models based in primary care settings,25,26 a critical part of our program is our partially grant-funded pharmacist. Although many buprenorphine treatment models in primary care settings have a dedicated nurse in a role similar to our pharmacist, in many primary care settings, filling a similar role with a nurse, nurse practitioner, or pharmacist may not be feasible. Despite these limitations, our findings add to the scant literature published on buprenophrine treatment outside of substance abuse treatment settings and outside of strict, time-intensive clinical trials.

Conclusions

Buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence in an urban community health center resulted in a 90-day retention rate of 71%. Type of substance use prior to starting buprenorphine treatment appeared to be associated with retention rates. High retention was associated with street methadone use, and low retention was associated with opioid analgesic and alcohol use prior to treatment. Of patients with urine toxicology tests, less than one fourth had tests positive for opioids. Findings from this evaluation can help physicians and health care administrators guide program development.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau, Special Projects of National Significance, Grant #6H97HA00247-04, and the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH AI-51519) Dr Cunningham is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program.

Footnotes

These findings were presented, in part, at the 6th International Conference on Urban Health, Amsterdam, Holland, October 2006.

Conflicts of interest: Dr Whitley gives talks sponsored by Reckitt Benckiser. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crane E. Narcotic analgesics. [Accessed November 18, 2007];The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Report. 2003 http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k3/pain/DAWNpain.pdf.

- 2.Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) Drug Policy Information Clearinghouse. [Accessed November 18, 2007];Heroin fact sheet. 2003 www.streetdrugs.org/pdf/Heroin2.pdf.

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies. [Accessed November 18, 2007];Rockville, Md: DAWN; Emergency department trends from the Drug Abuse Warning Network, final estimates 1995–2002. 2003 Series: D-24, DHHS publication no. (SMA) 03-3780 http://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/old_dawn/pubs_94_02/edpubs/2002final/files/EDTrendFinal02AllText.pdf.

- 4.Kakko J, Svanborg KD, Kreek MJ, Heilig M. One-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):662–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate Addiction. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1936–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball JC, Ross A. The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment: patients, programs, services, and outcome. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Clinical practice. Office-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):817–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sees KL, Delucchi KL, Masson C, et al. Methadone maintenance versus 180-day psychosocially enriched detoxification for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(10):1303–1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(18):1290–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor PG, Fiellin DA. Pharmacologic treatment of heroin-dependent patients. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):40–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy. Consultation document on opioid agonist treatment. [Accessed November 18, 2007];2003 www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/science%5Ftech/methadone/metha3.html.

- 13.Kissin W, McLeod C, Sonnefeld J, Stanton A. Experiences of a national sample of qualified addiction specialists who have and have not prescribed buprenorphine for opioid dependence. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(4):91–103. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n04_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunningham CO, Kunins HV, Roose RJ, Elam RT, Sohler NL. Barriers to obtaining waivers to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction treatment among HIV physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1325–1329. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0264-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpati A, Kerker B, Mostashari F, et al. Health disparities in New York City. [Accessed November 18, 2007];New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2004 www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/disparities-2004.pdf.

- 16.Olson EC, Van Wye G, Kerker B, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Take care Highbridge and Morrisania. [Accessed February 3, 2007];NYC community health profiles. (second edition). www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2006chp-106.pdf.

- 17.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction. [Accessed February 5, 2007];Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. 2004 DHHS publication no. (SMA) 04-3939. http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Bup%20Guide-lines.pdf. [PubMed]

- 19.Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–259. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1038–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Pakes JP, O’Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Treatment of heroin dependence with buprenorphine in primary care. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):231–241. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor PG, Oliveto AH, Shi JM, et al. A randomized trial of buprenorphine maintenance for heroin dependence in a primary care clinic for substance users versus a methadone clinic. Am J Med. 1998;105(2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan LE, Barry D, Moore BA, et al. A trial of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV clinical care. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43 suppl 4:S184–S190. doi: 10.1086/508182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu S, Smith-Rohrberg D, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Models for integrating buprenorphine therapy into the primary HIV care setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(5):716–721. doi: 10.1086/500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan LE, Bruce RD, Haltiwanger D, et al. Initial strategies for integrating buprenorphine into HIV care settings in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43 suppl 4:S191–S196. doi: 10.1086/508183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]