Abstract

Background

As the real clinical significance of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA19.9) evolution during preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases (CLM) is still unknown, we explored the correlation between biological and radiological response to chemotherapy, and their comparative impact on outcome after hepatectomy.

Methods

All patients resected for CLM at our hospital between 1990 and 2004 with the following eligibility criteria were included in the study: (1) preoperative chemotherapy, (2) complete resection of CLM, (3) no extrahepatic disease, and (4) elevated baseline tumor marker values. A 20% change of tumor marker levels while on chemotherapy was used to define biological response (decrease) or progression (increase). Correlation between biological and radiological response at computed tomography (CT) scan, and their impact on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) after hepatectomy were determined.

Results

Among 119 of 695 consecutive patients resected for CLM who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, serial CEA and CA19.9 were available in 113 and 68 patients, respectively. Of patients with radiological response or stabilization, 94% had similar biological evolution for CEA and 91% for CA19.9. In patients with radiological progression, similar biological evolution was observed in 95% of cases for CEA and in 64% for CA19.9. On multivariate analysis, radiological response (but not biological evolution) independently predicted OS. However, progression of CA19.9, but not radiological response, was an independent predictor of PFS.

Conclusions

In patients with CLM and elevated tumor markers, biological response is as accurate as CT imaging to assess “clinical” response to chemotherapy. With regards to PFS, CA19.9 evolution has even better prognostic value than does radiological response. Assessment of tumor markers could be sufficient to evaluate chemotherapy response in a nonsurgical setting, limiting the need of repeat imaging.

Hepatic resection is still considered the most effective treatment for patients with colorectal liver metastases (CLM).1 Unfortunately, only 10–20% of patients are directly amenable to surgery.2 In the remaining patients, complete metastatic resection would result in a too small volume of remnant functional liver parenchyma. However, due to major improvements in chemotherapy regimens, 13–54% of initially unresectable patients can now be switched to resectability.3–9 Besides this, systemic chemotherapy is increasingly being used in a neoadjuvant setting (i.e., in initially resectable patients) with the aim of facilitating hepatic resection and improving long-term outcome.10,11

To determine the efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy, computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard. Imaging studies are necessary to determine resectability. Furthermore, best surgical candidates can be identified, as disease progression while on preoperative chemotherapy is associated with poor outcome.12 Besides CT imaging, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and/or carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA19.9) are widely used to monitor patients while on chemotherapy. Although the prognostic significance of increased preoperative CEA and CA19.9 levels has been well established in large series, clinical significance of tumor marker evolution regarding correlation with imaging studies and impact on long-term outcome is still unclear.13–17 To date, only limited data is available suggesting a correlation between CEA evolution and chemotherapy response at CT imaging in patients with advanced colorectal cancer.18–20 As patient selection often was not well defined, data interpretation remains difficult. Recently, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommended CEA as the marker of choice for monitoring metastatic colorectal cancer during systemic therapy.21 On the contrary, insufficient data was available to recommend use of CA19.9 for evaluating treatment results in metastatic colorectal cancer patients.21

The aim of the present study is to explore the correlation between biological and radiological response following preoperative chemotherapy, and their comparative impact on long-term outcome, for both CEA and CA19.9, in a well-defined population of patients with isolated CLM, scheduled for hepatectomy.

Patients and Methods

Patients

All consecutive patients treated for CLM at our hospital between January 1990 and January 2004 with the following eligibility criteria were entered in the study: (1) treated by hepatectomy preceded by chemotherapy, (2) data for at least one tumor marker available, (3) primary tumor resected at least 6 months before last preoperative chemotherapy, (4) no extrahepatic disease diagnosed before or during hepatectomy, (5) CT reports before and after preoperative chemotherapy available, and (6) elevated tumor marker levels at baseline measurement (i.e., before preoperative chemotherapy). Patients were selected from our prospectively collected institutional database, and the medical record of each patient was reviewed.

Preoperative Management

Before hepatectomy, all patients were treated with at least one line of chemotherapy, either to achieve resectability in patients with initially unresectable CLM (i.e., inability to resect the total amount of CLM while leaving at least 30% future remnant liver volume) or in a neoadjuvant setting in patients with synchronous (i.e., diagnosed before, during or within 3 months after colorectal resection) or marginally resectable CLM (i.e., multinodular bilateral CLM).

In every patient, serum CEA and/or CA19.9 levels were routinely measured before, during, and after preoperative chemotherapy at our institution. Tumor markers were measured in fresh sera using Architect I2000SR CMIA technology (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL). Tumor marker levels <5 ng/ml for CEA and <37 U/ml for CA19.9 were considered normal.

Clinical response at CT imaging during chemotherapy was routinely evaluated every 2 months in a multidisciplinary staff meeting, including surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiologists. For every patient, the CT scan was reviewed by an expert radiologist blinded to tumor marker evolution, and type of radiological response after the last preoperative chemotherapy line was determined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).22

Hepatic Resection

All patients underwent hepatic resection with curative intent, after exploration by intraoperative ultrasound. If needed to allow resection, preoperative portal vein embolization was performed.23 Hepatic resections were classified as major (≥3 segments) or limited (<3 segments).24,25

Postoperative Follow-Up

Postoperatively, all patients were followed up regularly, starting 1 month after the operation and then every 4 months, consisting of clinical examination, serum tumor markers, abdominal ultrasound, and thoracoabdominal imaging. To reduce risk of recurrence, adjuvant chemotherapy was routinely recommended. If intra- and/or extrahepatic disease recurrence occurred which could be resected curatively, repeat resection was performed.26

Statistical Considerations

Mean tumor marker levels before and after the last preoperative chemotherapy were compared by paired-samples t test. To analyze the clinical significance of tumor marker evolution, a cutoff point of 20% change in tumor marker level after chemotherapy was chosen, as best agreement between radiological and biological response was observed when using this cutoff point, as assessed by the Cohen kappa test. A decrease of tumor marker level of 20% or more was defined as biological response. Likewise, an increase of tumor marker level of 20% or more was defined as biological progression. A decrease or increase of tumor marker level by less than 20% was considered as biological stabilization. To analyze the correlation between biological and radiological response after chemotherapy, as well as the impact of tumor marker evolution on survival, response and stabilization were grouped together (positive cases) and compared with progression (negative cases). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of tumor marker evolution were calculated, considering radiological response at CT imaging as reference standard.

Overall and progression-free survival curves were calculated by Kaplan–Meier method, and survivals of different groups were compared using log-rank tests. Survival rates were calculated from time of hepatectomy. Univariate associations between study variables (including patient, primary tumor, initial CLM, chemotherapy, and hepatectomy characteristics) and both overall and progression-free survival were determined by log-rank test P value ≤0.05. To identify independent predictors of overall and progression-free survival, factors with univariate P value ≤0.10 were entered in a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model. P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient Characteristics

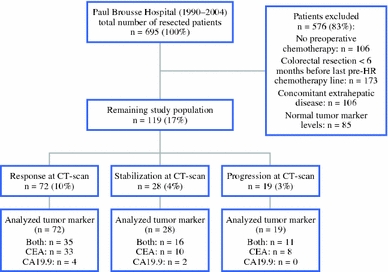

Between 1990 and 2004, 695 patients underwent hepatic resection for CLM at our hospital. Of these, 119 patients (17%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were subsequently enrolled in the study (Fig. 1). The study population consisted of 79 men (66%) and 40 women (34%), and mean age was 61 years (Table 1). In 95 patients (80%), the primary tumor was located in the colon. Forty-one patients (34%) presented with CLM synchronous to the primary colorectal malignancy. It concerned only one liver metastasis in 34 patients (30%), and metastases were initially unresectable in 55 patients (46%).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study population. HR hepatic resection, CT computed tomography, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA carbohydrate antigen

Table 1.

Patient and tumoral characteristics

| Characteristics | Total study population (N = 119) |

|---|---|

| Patients | |

| Mean age at HR, years ± SD | 61 ± 10 |

| Male/female | 79 (66%)/40 (34%) |

| Primary tumor | |

| Colon/rectum | 95 (80%)/24 (20%) |

| T classification | |

| 1 | 2 (2%) |

| 2 | 7 (8%) |

| 3 | 41 (49%) |

| 4 | 33 (40%) |

| N classification | |

| 0 | 33 (39%) |

| 1 | 28 (33%) |

| 2 | 24 (28%) |

| Liver metastases at initial diagnosis | |

| Synchronous/metachronousa | 41 (34%)/78 (66%) |

| Number of CLM | |

| 1 | 34 (30%) |

| 2–3 | 44 (38%) |

| >3 | 37 (32%) |

| Mean maximum size, mm ± SD | 46 ± 32 |

| Unilateral/bilateral | 61 (52%)/57 (48%) |

| Initial unresectability | 55 (46%) |

HR hepatic resection, SD standard deviation, CLM colorectal liver metastases

aSynchronous = diagnosed before, during, or within 3 months after colorectal resection

Preoperative Chemotherapy

Before hepatic resection, all patients were treated by at least one line of chemotherapy. A median number of 1 line (range 1–5) and a median number of 7 cycles (range 2–33) of systemic chemotherapy were administered. Radiological response of CLM after chemotherapy was observed in 72 patients (60%), stabilization in 28 (24%), and disease progression in 19 (16%). Chemotherapy details are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operative features

| Feature | Total study population (N = 119) |

|---|---|

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 119 (100%) |

| Total no. of lines | |

| 1 | 87 (73%) |

| >1 | 32 (27%) |

| Total no. of cycles | |

| <6 | 27 (24%) |

| ≥6 | 85 (76%) |

| Regimen last preoperative line | |

| 5-FU LV | 32 (27%) |

| 5-FU LV oxaliplatin | 61 (51%) |

| 5-FU LV irinotecan | 18 (15%) |

| Other | 8 (7%) |

| Chronomodulated delivery | 59 (50%) |

| Clinical response at CT scana | |

| Response | 72 (60%) |

| Stabilization | 28 (24%) |

| Progression | 19 (16%) |

| Change in CEA level after chemotherapy (N = 113)b | |

| Response | 75 (66%) |

| Stabilization | 14 (12%) |

| Progression | 24 (21%) |

| Change in CA19.9 level after chemotherapy (N = 68)b | |

| Response | 48 (71%) |

| Stabilization | 8 (12%) |

| Progression | 12 (18%) |

| Hepatectomy | |

| PVE | 14 (12%) |

| Major hepatectomy (≥3 segments) | 62 (52%) |

| Mean no. of CLM at histopathology ± SD | 3 ± 3 |

| Mean maximum size of CLM at histopathology, mm ± SD | 44 ± 36 |

| Surgical margin statusc | |

| R0 | 71 (60%) |

| R1 | 43 (36%) |

| R2 | 4 (3%) |

| Postoperative mortality (≤2 months) | 1 (1%) |

| Postoperative complications | 43 patients (36%) |

| Hepaticd | 31 (26%) |

| Generale | 20 (17%) |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 105 (88%) |

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, LV leucovorin, CT computed tomography, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA carbohydrate antigen, PVE portal vein embolization, CLM colorectal liver metastases, SD standard deviation

aAccording to RECIST criteria22

bCutoff point 20%

cR0: complete surgical resection with a negative surgical margin at histopathology; R1: invaded surgical margins according to the pathologist; R2: macroscopic tumor remnant intraoperatively

dHepatic complications considered were: biliary leak/bilioma, hemorrhage, infected collection, noninfected collection, and transient liver insufficiency

eGeneral complications considered were: pulmonary, cardiovascular, urinary tract, infectious (other than local hepatic), and iatrogenic complications

Tumor Marker Evolution

Data to determine the biological response were available in 113 cases for CEA and in 68 cases for CA19.9 (Fig. 1). Changes in tumor marker levels after chemotherapy within the total study population are shown in Table 2.

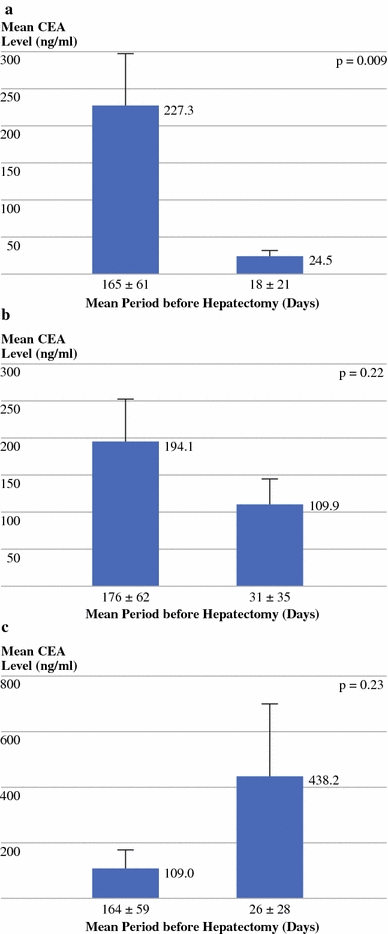

The mean CEA level after chemotherapy in patients with radiological response of CLM was significantly lower compared with the mean value before preoperative chemotherapy (Fig. 2a). If either stabilization or progression of CLM was observed following chemotherapy, mean CEA level did not significantly differ from that determined before starting preoperative chemotherapy (Fig. 2b, c). When using a cutoff point of 20% to define biological response, agreement between biological (CEA) and radiological response was observed in 80% of cases (90/113), with a kappa value of 0.62 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.49–0.76] (Table 3). Sensitivity was 94% (95% CI: 89–99%), specificity was 95% (95% CI: 85–105%), and PPV and NPV were 99% (95% CI: 97–101%) and 75% (95% CI: 58–92%), respectively.

Fig. 2.

Change of mean CEA level measured before and after last preoperative chemotherapy line in patients in whom radiological a response (N = 68), b stabilization (N = 26), or c progression (N = 19) of colorectal liver metastases was observed

Table 3.

Change of preoperative tumor marker levels (cutoff 20%) compared with clinical response at CT imaging after chemotherapy

| Clinical response at CTb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Stabilization | Progression | Total | |

| Change from preoperative CEA levela | ||||

| Response | 61 | 13 | 1 | 75 (66%) |

| Stabilization | 3 | 11 | 0 | 14 (12%) |

| Progression | 4 | 2 | 18 | 24 (21%) |

| Total | 68 (60%) | 26 (23%) | 19 (17%) | 113 (100%) |

| Change from preoperative CA19.9 levela | ||||

| Response | 38 | 9 | 1 | 48 (70%) |

| Stabilization | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 (12%) |

| Progression | 0 | 5 | 7 | 12 (18%) |

| Total | 39 (57%) | 18 (26%) | 11 (16%) | 68 (100%) |

CT computed tomography, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA carbohydrate antigen

aCutoff point 20%

bAccording to RECIST criteria22

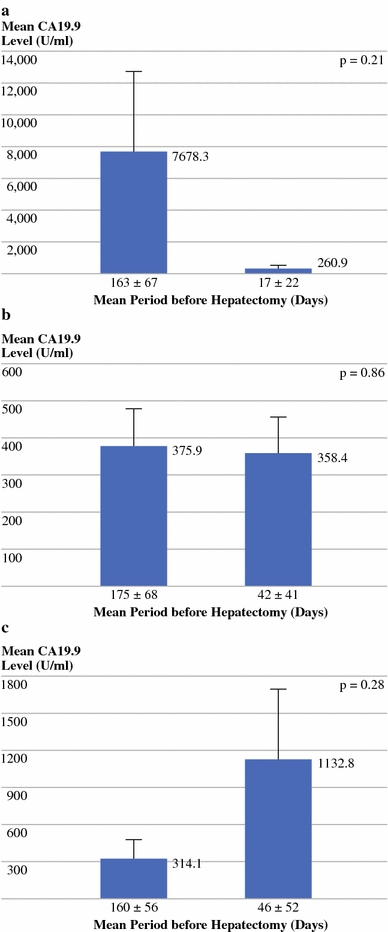

Although not statistically different, observed changes in mean CA19.9 levels measured before and after preoperative chemotherapy were in accordance with their corresponding radiological response categories, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a–c. Biological (CA19.9) and radiological response correlated favorably in 72% of cases (49/68), with a kappa value of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.25–0.59) (Table 3). Sensitivity was 91% (95% CI: 84–99%), specificity was 64% (95% CI: 35–92%), PPV was 93% (95% CI: 86–100%), and NPV was 58% (95% CI: 30–86%).

Fig. 3.

Change of mean CA19.9 level measured before and after last preoperative chemotherapy line in patients in whom radiological. a response (N = 39), b stabilization (N = 18), or c progression (N = 11) of colorectal liver metastases was observed

Hepatic Resection

To increase the volume of future remnant liver, preoperative portal vein embolization was performed in 14 patients (12%). Major hepatectomy was performed in 62 patients (52%), and any form of intraoperative vascular occlusion was needed in 96 patients (81%). Hepatic resection was both macroscopically and microscopically complete in 71 patients (60%) (Table 2). One patient (1%) died at the 19th postoperative day due to septic shock with multi-organ failure. Postoperative morbidity was 36% (51 complications: Clavien grade I/II, N = 42; grade III/IV, N = 9).27 Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered in the majority (88%) of patients.

Long-Term Outcome

After a mean follow-up of 34 months (45 months for surviving patients), 20 patients (17%) were alive and disease free, 18 (15%) were alive with disease recurrence, and 81 (68%) had died. Disease recurrence was diagnosed in 99 patients (83%). Repeat hepatectomy for intrahepatic recurrence was performed in 42% of patients, and 26 patients (22%) underwent resection of an extrahepatic recurrence.

Overall Survival (OS)

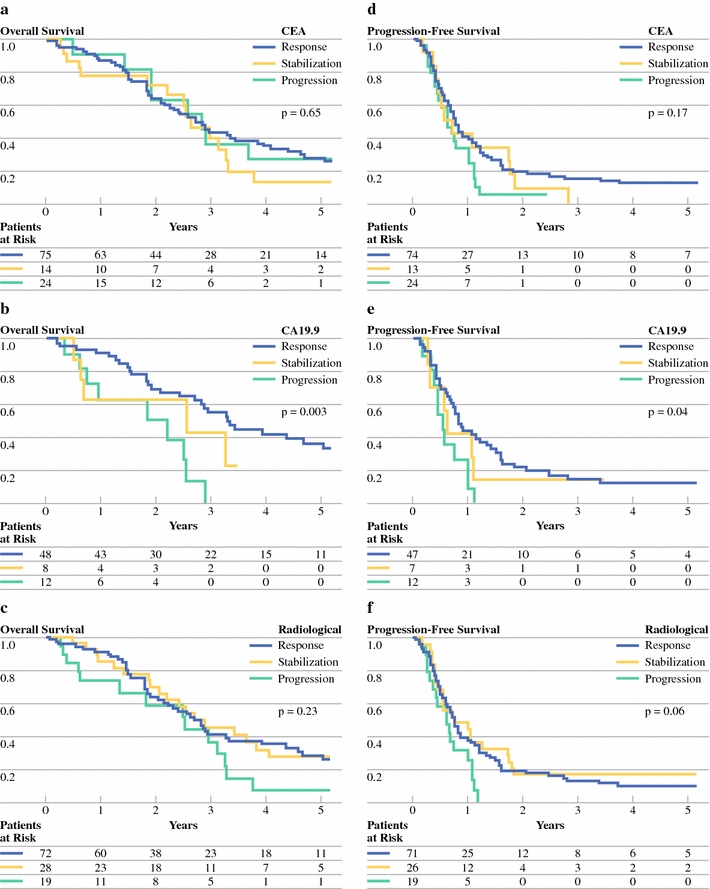

Considering the impact of CEA evolution on OS, 3- and 5-year OS were 44% and 28% if patients showed a response of CEA level after chemotherapy, 37% and 28% in case of stabilization, and 41% and 14% if CEA level had increased more than 20%, respectively (P = 0.65) (Fig. 4a). Median OS was 33 months in each group.

Fig. 4.

Impact of change of CEA level (a and d) and CA19.9 level (b and e) and radiological response (c and f) after preoperative chemotherapy on overall survival (a–c) and progression-free survival (d–f) (a cutoff point of 20% was used to define biological response, stabilization, and progression; radiological response was determined according to RECIST criteria22)

For CA19.9, 3- and 5-year OS were 55% and 36% in case of response, 40% and 0% when stabilized, and 0% and 0% when CA19.9 level had increased more than 20% (P = 0.003) (Fig. 4b). Median OS was 40 months in the response group, 31 months in the stabilization group, and 22 months in case of progression of CA19.9 levels.

When CLM showed a radiological response following preoperative chemotherapy, 3- and 5-year OS were 42% and 29%, respectively, compared with 46% and 28% if lesions were stabilized, and 36% and 7% if progression of CLM at CT imaging was observed (P = 0.23; median OS of 34, 32, and 30 months, respectively) (Fig. 4c).

Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

Median PFS was 9 months if CEA level responded after chemotherapy, compared with 7 months in both stabilization and progression groups (P = 0.17) (Fig. 4d).

Progression-free survival was significantly influenced by CA19.9 evolution, as none of the progressing patients was recurrence free after 3 years, compared with 16% and 14% of patients whose CA19.9 level showed response or stabilization, respectively (P = 0.04; median PFS was 10 months in the response group versus 7 months for both stabilization and progression groups) (Fig. 4e).

Finally, median PFS in case of radiological progression tended to be lower than that observed after radiological response or stabilization (7 months versus 9 months and 9 months, respectively; P = 0.06) (Fig. 4f).

Prognostic Factors of Overall Survival

On univariate analysis, study variables that were associated with poor OS were synchronous CLM, ≥4 CLM at diagnosis, diameter of largest metastasis ≥35 mm, bilateral CLM, initial unresectability, and progression of CA19.9 level after preoperative chemotherapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival

| Variable | N | 5-Year OS (%) | UV P | MVa P | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 119 | 26 | |||

| Patient factors | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 79 | 23 | 0.12 | – | – |

| Female | 40 | 30 | |||

| Age at hepatectomy | |||||

| <60 years | 46 | 21 | 0.49 | – | – |

| ≥60 years | 73 | 29 | |||

| Primary malignancy | |||||

| Location | |||||

| Colon | 95 | 25 | 0.73 | – | – |

| Rectum | 24 | 29 | |||

| T classification | |||||

| 1–2 | 9 | 22 | 0.24 | – | – |

| 3–4 | 74 | 24 | |||

| N classification | |||||

| 0 | 33 | 25 | 0.77 | – | – |

| 1–2 | 52 | 18 | |||

| CLM at diagnosis | |||||

| Timing of diagnosisb | |||||

| Synchronous | 41 | 14 | 0.009 | NS | – |

| Metachronous | 78 | 33 | |||

| No. of CLM | |||||

| <4 | 78 | 32 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.6–4.3) |

| ≥4 | 37 | 17 | |||

| Max. size of CLM | |||||

| <35 mm | 50 | 34 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 2.2 (1.3–3.7) |

| ≥35 mm | 58 | 16 | |||

| Distribution | |||||

| Unilateral | 61 | 35 | 0.004 | NS | – |

| Bilateral | 57 | 16 | |||

| Initial resectability | |||||

| Yes | 64 | 40 | 0.01 | NS | – |

| No | 55 | 15 | |||

| Hepatic resection | |||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |||||

| Total no. of lines | |||||

| 1 | 87 | 30 | 0.6 | – | – |

| ≥2 | 32 | 13 | |||

| Total no. of cycles | |||||

| <10 | 72 | 34 | 0.13 | – | – |

| ≥10 | 40 | 7 | |||

| Regimen last preoperative line | |||||

| 5-FU LV | 32 | 25 | 0.17 | – | – |

| 5-FU LV oxaliplatin | 61 | 32 | |||

| 5-FU LV irinotecan | 18 | 16 | |||

| Other | 8 | 0 | |||

| Chronomodulated therapy | |||||

| Yes | 59 | 28 | 0.57 | – | – |

| No | 60 | 23 | |||

| Radiological response at CT scanc | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 100 | 29 | 0.09 | 0.004 | 2.6 (1.3–4.9) |

| Progression | 19 | 7 | |||

| Biological response, CEAd | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 89 | 28 | 0.36 | – | – |

| Progression | 24 | 14 | |||

| Biological response, CA19.9d | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 56 | 33 | 0.002 | NS | – |

| Progression | 12 | 0 | |||

| Extent of hepatic resection | |||||

| Minor (<3 segments) | 57 | 32 | 0.06 | NS | – |

| Major (≥3 segments) | 62 | 20 | |||

| Resection type | |||||

| Anatomical | 58 | 31 | 0.49 | – | – |

| Nonanatomical | 26 | 29 | |||

| Both | 35 | 12 | |||

| Vascular occlusion | |||||

| Yes | 97 | 25 | 0.95 | – | – |

| No | 17 | 30 | |||

| Intraoperative RBC transfusion | |||||

| Yes | 32 | 25 | 0.85 | – | – |

| No | 60 | 30 | |||

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 105 | 27 | 0.37 | – | – |

| No | 11 | 12 | |||

| Surgical margin statuse | |||||

| R0 | 71 | 28 | 0.16 | – | – |

| R1 | 43 | 21 | |||

| R2 | 4 | 25 | |||

OS overall survival, UV univariate, MV multivariate, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CLM colorectal liver metastases, NS not significant, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil, LV leucovorin, CT computed tomography, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA carbohydrate antigen, RBC red blood cell

aVariables with univariate P ≤ 0.10 were entered in the Cox regression model

bSynchronous = diagnosed before, during, or within 3 months after colorectal resection

cAccording to RECIST criteria22

dCutoff point 20%

eR0: complete surgical resection with a negative surgical margin at histopathology; R1: invaded surgical margins according to the pathologist; R2: macroscopic tumor remnant intraoperatively

After introducing all factors with univariate P ≤ 0.10 in a Cox proportional hazard model, three factors were identified as independent predictors of poor OS: ≥4 CLM at diagnosis, largest metastasis diameter ≥35 mm, and radiological (but not biological) progression of CLM following preoperative chemotherapy (Table 4).

Prognostic Factors of Progression-Free Survival

On univariate analysis, nine factors were identified which significantly influenced PFS: female gender, synchronous CLM, ≥3 CLM at diagnosis, bilateral CLM, type of last preoperative chemotherapy, radiological response following chemotherapy, biological response of CA19.9 level after chemotherapy, administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, and surgical margin status after hepatectomy (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of progression-free survival

| Variable | N | 5-Year PFS (%) | UV P | MVa P | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 116 | 9 | |||

| Patient factors | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 76 | 20 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.9 (1.0–3.5) |

| Female | 40 | 3 | |||

| Age at hepatectomy | |||||

| <70 years | 92 | 9 | 0.85 | – | – |

| ≥70 years | 24 | 10 | |||

| Primary malignancy | |||||

| Location | |||||

| Colon | 93 | 9 | 0.44 | – | – |

| Rectum | 23 | 10 | |||

| T classification | |||||

| 1–2 | 9 | 0 | 0.64 | – | – |

| 3–4 | 72 | 9 | |||

| N classification | |||||

| 0 | 32 | 8 | 0.91 | – | – |

| 1–2 | 51 | 5 | |||

| CLM at diagnosis | |||||

| Timing of diagnosisb | |||||

| Synchronous | 39 | 3 | 0.05 | NS | – |

| Metachronous | 77 | 13 | |||

| No. of CLM | |||||

| <3 | 62 | 18 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) |

| ≥3 | 50 | 0 | |||

| Max. size of CLM | |||||

| <35 mm | 48 | 15 | 0.28 | – | – |

| ≥35 mm | 57 | 6 | |||

| Distribution | |||||

| Unilateral | 58 | 18 | 0.006 | NS | – |

| Bilateral | 57 | 0 | |||

| Initial resectability | |||||

| Yes | 63 | 18 | 0.28 | – | – |

| No | 53 | 3 | |||

| Hepatic resection | |||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |||||

| Total no. of lines | |||||

| 1 | 86 | 9 | 0.97 | – | – |

| ≥2 | 30 | 10 | |||

| Total no. of cycles | |||||

| <10 | 69 | 11 | 0.08 | NS | – |

| ≥10 | 40 | 4 | |||

| Regimen last preoperative line | |||||

| 5-FU LV | 31 | 10 | 0.03 | NS | – |

| 5-FU LV oxaliplatin | 61 | 12 | |||

| 5-FU LV irinotecan | 16 | 6 | |||

| Other | 8 | 0 | |||

| Chronomodulated therapy | |||||

| Yes | 59 | 9 | 0.89 | – | – |

| No | 57 | 10 | |||

| Radiological response at CT scanc | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 97 | 11 | 0.02 | NS | – |

| Progression | 19 | 0 | |||

| Biological response, CEAd | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 87 | 10 | 0.07 | NS | – |

| Progression | 24 | 0 | |||

| Biological response, CA19.9d | |||||

| Response or stabilization | 54 | 13 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 3.2 (1.6–6.6) |

| Progression | 12 | 0 | |||

| Extent of hepatic resection | |||||

| Minor (<3 segments) | 54 | 13 | 0.31 | – | – |

| Major (≥ 3 segments) | 62 | 6 | |||

| Resection type | |||||

| Anatomical | 57 | 14 | 0.12 | – | – |

| Nonanatomical | 24 | 9 | |||

| Both | 35 | 0 | |||

| Vascular occlusion | |||||

| Yes | 95 | 8 | 0.49 | – | – |

| No | 17 | 18 | |||

| Intraoperative RBC transfusion | |||||

| Yes | 32 | 6 | 0.90 | – | – |

| No | 58 | 13 | |||

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 105 | 10 | 0.009 | NS | – |

| No | 10 | 0 | |||

| Surgical margin statuse | |||||

| R0 | 69 | 13 | 0.04 | NS | – |

| R1 | 42 | 3 | |||

| R2 | 4 | 0 | |||

PFS progression-free survival, UV univariate, MV multivariate, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CLM colorectal liver metastases, NS not significant, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil, LV leucovorin, CT computed tomography, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA carbohydrate antigen, RBC red blood cell

aVariables with univariate P ≤ 0.10 were entered in the Cox regression model

bSynchronous = diagnosed before, during, or within 3 months after colorectal resection

cAccording to RECIST criteria22

dCutoff point 20%

eR0: complete surgical resection with a negative surgical margin at histopathology; R1: invaded surgical margins according to the pathologist; R2: macroscopic tumor remnant intraoperatively

On multivariate analysis, female gender, ≥3 CLM at diagnosis, and progression of CA19.9 level after chemotherapy, but not radiological progression, were independent predictors of decreased PFS (Table 5).

Discrepancies Between Biological and Radiological Evolution

Of patients in whom CEA level had increased more than 20% during chemotherapy treatment (N = 24), response or stabilization was observed at CT imaging in six patients. In addition, of 89 patients whose CEA level showed response or stabilization during chemotherapy, one had progression of disease at CT imaging. All of these patients developed disease recurrence shortly after hepatic resection (median 7 months), and three of them had died at last follow-up.

When progression of CA19.9 levels was observed during chemotherapy (N = 12), five patients had radiological response or stabilization. Furthermore, of 56 patients with response or stabilization of CA19.9 level during chemotherapy, 4 had radiological progression of disease. Again, all of these patients recurred shortly after hepatic resection (median 6 months), and at last follow-up seven had died of disease progression.

Discussion

As the decisional value of tumor marker evolution during chemotherapy in patients scheduled for hepatic resection of CLM is still unclear, we aimed to define the correlation between biological and radiological response following preoperative chemotherapy as well as their impact on long-term outcome in this particular patient group.

In the present study, CEA evolution was found to be highly correlated with radiological response after preoperative chemotherapy, with sensitivity and specificity rates exceeding 90%. However, while radiological progression independently predicted decreased OS, change in CEA level after chemotherapy did not significantly impact long-term outcome, although a trend for decreased survival was observed in patients with increased CEA level (5-year OS 14% versus 28%).

Sensitivity of CA19.9 evolution was comparable to that observed for CEA, with however, a lower specificity. In contrast to CEA evolution, progression of CA19.9 level during chemotherapy had negative impact on both OS and PFS. In addition, progression of CA19.9 level after chemotherapy, but not radiological response, was an independent predictor of poor PFS.

In several large patient series, various cutoff points of elevated tumor marker levels before hepatectomy for CLM have been related to worse long-term outcome.13–17 However, little evidence exists regarding the decisional value of biological response during chemotherapy. In only four publications was the correlation between biological and radiological response analyzed.18–20,28 Ward et al. assessed the accuracy of tumor marker evolution (CEA, CA-195, and CA-242) in monitoring patients treated by chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer. In that study, CEA was found to have the best predictive value in monitoring disease course during chemotherapy, which correlated favorably with radiological changes in 88% of patients.20 More recently, Wang et al. reported a lower rate of agreement between imaging studies and change in CEA level (68%).19 In 2006, Boppudi et al. concluded that there existed a major lack of agreement between tumoral changes at CT imaging and changes in CEA level in patients treated by selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) for unresectable CLM.28 Finally, Iwanicki-Caron et al. recently reported that CEA kinetics is an accurate method to identify disease progression in patients with advanced colorectal cancer.18 Importantly, these studies included only patients treated in a nonsurgical setting, with colorectal metastases not only confined to the liver, normal baseline CEA levels in some of them, thereby hampering data interpretation, and no evaluation of CA19.9 kinetics. As the value of CEA and CA19.9 evolution still remains a matter of debate, we decided to define both the correlation between biological and radiological response on chemotherapy and their comparative impact on long-term outcome, in a well-defined population of patients with isolated CLM who were all treated by chemotherapy followed by hepatic resection and all of whom had elevated baseline tumor marker levels. In this way, it was logical to assume that tumor marker levels were only related to liver metastases, thereby enabling us to draw reliable conclusions. In addition, as more than two-thirds of our patients were treated by modern chemotherapy regimens, and by using the RECIST criteria, our results reflect current standard of care. However, although strict inclusion criteria were used, some variation exists in the severity of metastatic disease and in the type of chemotherapy used within this “surgical” population.

When using a cutoff point of 20% change to define biological response after chemotherapy, biological response correlated favorably with radiological response in 80% and 72% of patients, with kappa values of 0.62 and 0.46, when either CEA or CA19.9 was analyzed, respectively. It was noteworthy that patients in whom discrepancy existed between radiological and biological response all recurred shortly after hepatectomy, and most of them had died at last follow-up. Therefore, determining biological response after chemotherapy provides important additional information, as patients whose metastases did not progress radiologically but who did demonstrate biological progression had similar prognosis compared with patients whose metastases showed radiological progression.

Concerning the correlation between biological and radiological response to chemotherapy, an important question that arises is whether tumor marker evolution should replace radiological evaluation. In patients with potentially resectable CLM, CT imaging remains the gold standard in evaluating chemotherapy results, as it enables evaluation of technical resectability of CLM. However, radiological evaluation should be combined in these patients with biological response, as this most accurately evaluates chemotherapy response and thus provides the best information regarding long-term outcome. Although we have studied a “surgical” population, almost half of the patients (46%) were initially unresectable, and might not have been treated surgically in less specialized centers. Therefore, our results concerning biological and radiological correlation might also be applicable for a nonsurgical population. Thus, the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy administered in a nonsurgical treatment setting can be adequately monitored by determining biological response, thereby lowering the need for imaging studies. In this way, a reduction in health care costs could be achieved, combined with an improvement in patient comfort. Whether this hypothesis is true or not should be confirmed in future studies.

In our study, CEA evolution did not significantly influence OS and PFS, which is in contrast with the results reported by Iwanicki-Caron et al., Wang et al. and Boppudi et al., since in these series decrease in CEA level was significantly related to better survival.18,19,28 This could be related to the fact that, in some of the cited studies, patients with normal baseline tumor marker levels were also analyzed. In contrast, in our series, progression of CA19.9 level significantly influenced OS, and more importantly, it independently predicted poor PFS, thereby emphasizing its importance in estimating individual outcome. The value of CA19.9 evolution in patients with CLM treated by preoperative chemotherapy has to our knowledge never been explored, and it is noteworthy that it could be more accurate than CEA. Radiological progression of CLM following preoperative chemotherapy was found to be an independent predictor of poor OS, which is in accordance with our previous publication reporting a similar relationship between radiological progression and long-term outcome.12

In summary, the results of this study clearly show that, in patients with CLM treated by systemic chemotherapy, biological response (as measured by both CEA and CA19.9) and radiological response are closely correlated. Furthermore, CA19.9 evolution is an even better prognostic tool than radiological response with regards to PFS. In patients treated by systemic chemotherapy in a nonsurgical treatment setting, biological response can decrease the need for imaging studies. In addition, in patients with potentially resectable CLM, although CT imaging remains irreplaceable to determine resectability, biological response can provide relevant complementary information concerning individual outcome. In the future, our results need to be confirmed by other studies.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Scheele J, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:313–327. doi: 10.1007/s004230050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam R. Chemotherapy and surgery: new perspectives on the treatment of unresectable liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2003;14 Suppl 2:ii13–ii16. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, Avisar E, Ariche A, et al. Five-year survival following hepatic resection after neoadjuvant therapy for nonresectable colorectal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam R, Aloia T, Lévi F, et al. Hepatic resection after rescue cetuximab treatment for colorectal liver metastases previously refractory to conventional systemic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4593–4602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberts SR, Horvath WL, Sternfeld WC, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for patients with unresectable liver-only metastases from colorectal cancer: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9243–9249. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Camara J, Rodriguez J, Rotellar F, et al. Triplet therapy with oxaliplatin, irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid within a combined modality approach in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;23:3593. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masi G, Cupini S, Marcucci L, et al. Treatment with 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan enables surgical resection of metastases in patients with initially unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:58–65. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pozzo C, Basso M, Cassano A, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable liver disease with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid in colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:933–939. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quenet F, Nordlinger B, Rivoire M, et al. Resection of previously unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (LMCRC) after chemotherapy (CT) with CPT-11/L-OHP/LV5FU (Folfirinox): a prospective phase II trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;23:3613. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen PJ, Kemeny N, Jarnagin W, DeMatteo R, Blumgart L, Fong Y. Importance of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients undergoing resection of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:109–115. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam R, Pascal G, Castaing D, et al. Tumor progression while on chemotherapy: a contraindication to liver resection for multiple colorectal metastases? Ann Surg. 2004;240:1052–1061. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000145964.08365.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, et al. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644–657. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000145964.08365.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Torzilli G, et al. Extension of the frontiers of surgical indications in the treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2000;231:487–499. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200004000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Jaeck D. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Française de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1254::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Paul M. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00316981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwanicki-Caron I, Di Fiore F, Roque I, et al. Usefulness of the serum carcinoembryonic antigen kinetic for chemotherapy monitoring in patients with unresectable metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3681–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang WS, Lin JK, Lin TC, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen in monitoring of response to systemic chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:96–101. doi: 10.1007/s003840000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward U, Primrose JN, Finan PJ, Perren TJ, Selby P, Purves DA, Cooper EH. The use of tumour markers CEA, CA-195 and CA-242 in evaluating the response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Locker GY, Hamilton S, Harris J, et al. ASCO 2006 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in gastrointestinal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5313–5327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay D, Castaing D, Smail A, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after percutaneous portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2000;231:480–486. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200004000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bismuth H. Surgical anatomy and anatomical surgery of the liver. World J Surg. 1982;6:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01656368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couinaud C. Le foie: études anatomiques et chirurgicales. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam R, Bismuth H, Castaing D, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 1997;225:51–60. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boppudi S, Wickremesekera SK, Nowitz M, Stubbs R. Evaluation of the role of CT in the assessment of response to selective internal radiation therapy in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Australas Radiol. 2006;50:570–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2006.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]