Abstract

We have recently shown that phospho-cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is essential but not sufficient for activation of CRH transcription, suggesting the requirement of a coactivator. Here, we test the hypothesis that the CREB coactivator, transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC), is required for activation of CRH transcription, using the cell line 4B and primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Immunohistochemistry and Western blot experiments in 4B cells revealed time-dependent nuclear translocation of TORC1,TORC 2, and TORC3 by forskolin [but not by the phorbol ester, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)] in a concentration-dependent manner. In reporter gene assays, cotransfection of TORC1 or TORC2 potentiated the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH promoter activity but had no effect in cells treated with PMA. Knockout of endogenous TORC using silencing RNA markedly inhibited forskolin-activated CRH promoter activity in 4B cells, as well as the induction of endogenous CRH primary transcript by forskolin in primary neuronal cultures. Coimmunoprecipitation and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments in 4B cells revealed association of CREB and TORC in the nucleus, and recruitment of TORC2 by the CRH promoter, after 20-min incubation with forskolin. These studies demonstrate a correlation between nuclear translocation of TORC with association to the CRH promoter and activation of CRH transcription. The data suggest that TORC is required for transcriptional activation of the CRH promoter by acting as a CREB coactivator. In addition, cytoplasmic retention of TORC during PMA treatment is likely to explain the failure of phorbolesters to activate CRH transcription in spite of efficiently phosphorylating CREB.

Activation of CRH transcription requires nuclear translocation and binding of the CREB co-activator, TORC, to the corticotrophin releasing hormone promoter.

Preservation of a constant internal environment requires continuous adaptation to external and internal disturbances. This involves behavioral, visceral, and endocrine changes necessary for maintaining homeostasis. The major endocrine adaptation is via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in rapid increases in circulating ACTH and subsequent rise in glucocorticoids, which is critical for successful adaptation (1,2,3). However, excessive glucocorticoid secretion, or simply alterations in its circadian rhythm, can lead to negative changes, including immune suppression, cell death, and psychiatric disturbances such as depression (4,5). The major regulator of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity (and glucocorticoid secretion) is the hypothalamic neuropeptide, CRH. In addition to regulating pituitary ACTH secretion, CRH is released within the brain, where it mediates behavioral and autonomic adaptation to stress, by acting upon receptors located in limbic areas of the brain (6,7). CRH release during stress is associated with rapid increases in CRH transcription in the paraventricular nucleus, which are necessary to replenish CRH mRNA and peptide levels after its release (8,9,10). Therefore, elucidation of mechanisms controlling CRH transcription is essential for understanding the pathophysiology and treatment of stress-related disorders.

It is well established that cAMP induces CRH expression through activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and recruitment of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) by the CRE of the CRH promoter (11,12,13). Although a number of signaling pathways lead to CREB phosphorylation (14), cAMP signaling is required to increase CRH expression (11,15). Also, microinjection of both 8-bromo-cAMP and the phorbol ester, phorbol myristrate acetate (PKC stimulator) in the paraventricular nucleus increase plasma ACTH and pituitary proopiomelanocortin mRNA levels, but only cAMP augments CRH mRNA levels (16). Recent studies demonstrating that both forskolin (stimulant of adenylate cyclase) and phorbol esters (stimulant of PKC) induce CREB phosphorylation but that only forskolin activates CRH transcription indicate that phospho-CREB alone cannot drive CRH transcription (15). Although not sufficient, CREB is required for CRH promoter activation because the CREB dominant negative, A-CREB, blunts the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH promoter activity (15). These data strongly suggest that activation of CRH transcription requires a cAMP-dependent CREB coactivator. A similar requirement for a coactivator has been demonstrated for phospho-CREB-dependent regulation of gluconeogenic enzymes (17,18,19). Similar to CRH transcription, both insulin and glucagon induce CREB phosphorylation but they have opposite effects on gluconeogenic enzyme transcription in the liver (17,19). This is due to divergent inactivating effect of insulin and activating effect glucagon on nuclear translocation and activity of the CREB coactivator, TORC2 (transducer of regulated CREB activity 2).

The aim of the present studies is to test the hypothesis that TORC acts as a CREB coactivator during activation of CRH transcription. For this purpose, we used the hypothalamic neuronal cell line, 4B, and primary cultures of rat hypothalamic cells to examine the ability of forskolin and PMA to induce nuclear translocation of TORC and its binding to the CRH promoter and to activate the CRH promoter. In addition, reporter gene assays and measurement of CRH primary transcript [heteronuclear RNA (hnRNA)] were used to study the effects of overexpressing or knocking out TORC on CRH transcription.

Materials and Methods

Constructs and reagents

The rat CRH promoter-driven luciferase reporter gene (pGL3-CRHp) was described previously (11). Because cotransfection of TORC expression vectors caused marked changes in the promoterless pGL3 reporter vector, a second reporter construct (pGL4-CRHp) was created by subcloning the CRH promoter obtained by PCR from pGL3-CRHp into the BglII/Xhol sites of pGL4.14 (Promega, Madison, WI). The vector pGL4.14 is less efficient as pGL3 as a reporter vector, but it provides a reasonable tool to assess promoter activity without significant interference of intrinsic vector backbone regulated activity. The PCR primers containing the BglII and Xho1 restriction sites were as follow: 5′-ACTGATCTCGAGGGATCTTTCCTGAGAGTACAAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATCAGAGATCTCTCAGGATGCCTCCTGCAGGTTTTC-3′ (reverse). Expression vectors for human TORC1 and TORC2 were kindly provided by Marc Montminy (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA). Plasmids harboring rat TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3 cDNA fragments [used to construct standard curves for mRNA quantification by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)] were generated by cloning the PCR fragments into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The sequence of the PCR primers were as follow: 5′-TATGGCACCGTGTACCTCTCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGTGGATGGTGCTGAGGTCAG-3′ (reverse) for TORC1; 5′-AAGTCTAGTTATACCCAGCCATCC-3′(forward) and 5′-TCACTGTAGCCGATCACTACGGAATG-3′(reverse) for TORC2 and 5′-ACACCCTGACGGTAGTCACAGCATAG-3′(forward) and 5′-AAGATGGAGGGCATTGTGTGCAGG-3′ (reverse) for TORC3.

Silencing RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides against TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3 and the negative control, silence inactive control #1 siRNA, were purchased from Ambion/Applied Biosystems (Austin, TX). The oligonucleotide sequences were as follow: TORC1: 5′-UGGACGAGCUGAAAAUUGAtt-3′; TORC2: 5′-GGUCCUGGAUUUUUAGGGAtt-3′, and TORC3 5′-GACCAAUUCUGAUUCUGCUtt-3′. Other reagents were purchased from commercial sources as indicated in the text.

Cell cultures, transfection, and treatments

Hypothalamic 4B cells, provided by John Kasckow (Cincinnati, OH), were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (20). For reporter gene assays, cells were transfected by electroporation using a Nucleofector (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD) and solution V purchased from the manufacturer, as previously described (15,20). To determine the effect of TORC overexpression on CRH promoter activity, cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of CRHp-pGL4.14, 30 ng of renilla luciferase, and 100 ng of TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 expression constructs. Transfection of TORC expression vectors had little or absent effect on the promoterless pGL4-reporter construct; 16–18 h after transfection, cells were changed into serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA and 1 h later incubated for 6 h with forskolin (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) at concentrations previously shown to stimulate CRH transcription (15) or the phorbol ester 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), in the conditions described in Results and figure legends. Cells were then washed in PBS and lysed in 100 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega) for measurement of luciferase activity using reagents from Promega (Dual Luciferase Assay System).

Primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons were prepared from fetal Sprague Dawley rats, embryonic d 18, by collagenase dispersion and plated in six-well plates as previously described (15). All animal procedures were approved by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Animal Care and Use Committee. After 24 h in the presence of serum, cultures were maintained for eight additional days in neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement (Life Technologies, Inc., Invitrogen). Cytosine arabinoside (Sigma), to a final concentration of 5 μm, was added from d 4 to prevent glial proliferation. On d 10, cells were transfected with 20 nm of siRNA or nonspecific oligonucleotide, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) following the manufacturers protocol. After 4 h with Lipofectamine, cultures were returned to neurobasal with B27 supplement for 24 h before changing into B27 supplement-free neurobasal medium containing 0.1% BSA for 2 h before treatment in the conditions described in Results and figure legends.

Western blot analyses

Nuclear extracts from 4B cells were prepared using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Western blot analysis for phospho-CREB, β actin, and histone deacetylase 1, TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3 was performed as previously described (15) with the following modifications. For TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3, 15 μg of cytoplasmic or nuclear extract were loaded and separated in a 6% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen). Gels were run until the 50 kDa marker (Prestained protein ladder, Fermentas, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD) ran off the gel, to separate phospho- or dephospho-TORCs. The primary antibodies were anti-TORC1 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), at 1:1000 dilution, anti-TORC2 (Calbiochem/EDM Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ), at 1:2000 dilution, and anti-TORC3 (Cell Signaling), at 1:1000 dilution. After washing and incubating with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase labeled secondary antibody, immunorective bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence plus detection system and film exposure (15). The intensity of the bands was quantified using a computer image analysis system, ImageJ (developed at the National Institutes of Health, which is freely available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov).

Immunostaining for TORC2 in 4B cells

Hypothalamic 4B cells cultured on poly-lysine-coated coverslips were treated either with vehicle [dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 0.1%] or forskolin, 0.3 and 3 μm for 30 min or 3 h, before fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min. Coverslips were washed in PBS, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in the same solution containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and 5% normal goat serum to block nonspecific binding of the antibody. Coverslips were then incubated overnight at 4 C with anti-TORC2 antibody (Calbiochem), 1:500 dilution in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and 1% normal goat serum. On the next day, coverslips were washed with PBS (3 × 5 min) and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 goat antirabbit IgG (1:1000, Molecular Probes; Invitrogen) in the same buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After 6 × 10 min washes in PBS, coverslips were mounted on slides with Vectashield fluorencescence mounting medium (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Coverslips processed in the absence of primary antibody served as negative controls for immunostaining. Images of cell cultures were taken as a single plane scans on a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at ×63 magnification. Digitized images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, Mountain View, CA). Because a number of antibodies tested for other TORC subtypes were not suitable for immunohistrochemistry, these experiments had to be limited to TORC2.

Coimmunoprecipitation of CREB and TORC2

The presence of physical interaction between phospho-CREB and TORC2 was examined in 4B cells transfected with 2.5 μg of FLAG-TORC2 expression vector/5 million cells, using a Nucleofector (Amaxa). After transfection, aliquots of 5 million cells were plated in 10-cm culture dishes. After overnight incubation in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 10% horse serum, cells were changed to DMEM containing 0.1% BSA for 2 h before addition of vehicle or 3 μm forskolin or 0.1 μm PMA. After 20-min incubation, dishes were placed on ice, washed three times with cold PBS scraped out in 1 ml of ice-cold PBS containing phosphatase/protease inhibitors cocktail (Pierce), transferred to a 1.5 microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged for 3 min at 4 C at 500 × g. Nuclear proteins extraction and coimmunoprecipitation procedures were performed using the Nuclear Complex Coimmunoprecipitation kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Nuclear proteins (100 μg) were immunoprecipitated by overnight incubation with mouse anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or mouse IgG (used as negative control) at 4 C. Protein-antibody immune complexes were separated using protein G magnetic beads (Active Motif) for 1 h at 4 C, washed (three times) and resuspended in 2× Reducing Loading Buffer (Invitrogen) for Western blot analysis.

Chromatin immuprecipitation (ChIP) assay

To determine whether forskolin induces binding of TORC to the CRH promoter, we performed ChIP assays. Because current passages of 4B cells do not express detectable levels of endogenous CRH, cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of CRHp-Luc using a Nucleofector (Amaxa/Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and aliquots containing 5 million cells plated in 10-cm culture dishes; 22–24 h after transfection, cells were changed into serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA and 2 h later incubated for 20 min with forskolin (Biomol). ChIP assays were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (Active Motif). Briefly, the DNA-protein complexes in cells were cross-linked with 4% formaldehyde and the reaction terminated by addition of glycine. The cells were lysed, and the nuclei sonicated eight cycles of 30-sec on and 30-sec off at high-level output (Bioruptor from Diagenode, Liège, Belgium) in shearing buffer with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors to generate 0.2- to 1-kb DNA fragments of chromatin. Immunoprecipitation was performed on 15 μg of chromatin with either anti-TORC2 antibody (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX) or CREB antibody (Upstate/Millipore, Temecula, CA) or rabbit IgG for negative control at 4 C under rotation overnight. DNA-protein immuno-complexes were collected using protein G magnetic beads, washed, eluted, reverse cross-linked, and treated with proteinase K. Immunoprecipitated CRH promoter was quantified using RT-PCR with primers designed to amplify the region encompassing the 112 bp containing the CRE (forward, 5′-tcagtatgttttccacacttggat and reverse, 5′- tttatcgcctccttggtgac-3′).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR for CRH hnRNA and TORC mRNA

After treatment, primary neurons were harvested in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA prepared and purified as previously described (15). RT into cDNA was performed as described using 350–700 ng of total RNA per sample. Endogenous CRH transcription was measured as the levels of primary CRH transcript or CRH hnRNA by qRT-PCR using primers targeting the intron of the CRH gene. The sequences of the primers are forward CCTCAGCAGTCTGGAGGTTC and reverse TAAGGGCTGAAGCGAACTGT. Power SYBR green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for the amplification mixture with each primer at a final concentration of 200 nm and 2 μl of cDNA for a total reaction volume of 25 μl. The primers for TORC qRT-PCR are: forward GAGAAGATCGCACTGCACAA and reverse AGGAGAGGTCCATGCTGCTA for TORC1; forward GTGGTTCTCTGCCCAATGTT and reverse GGCAGGGCTATAGGGAGAAC for TORC2; and forward ACAACTGTGGGAGACCAAGG and reverse CCAAAGAGGTGGTCACTGGT for TORC3. PCRs were performed on spectrofluorometric thermal cycler (ABI PRISM 7300 RT-PCR system; Applied Biosystems), as previously described. Samples were amplified by an initial denaturation at 50 C for 2 min, 95 C for 10 min, and then cycled (45×) using 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 45 sec.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of the differences between groups was calculated by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls method for pairwise multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± sem from the values in the number of observations indicated in Results or legends to figures.

Results

Forskolin but not PMA induces nuclear translocation of TORC2 in 4B cells

Preliminary experiments using qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses revealed that all three forms of TORC mRNA and protein are present in 4B cells. Quantitative analysis of TORC mRNA using standard curves from rat TORC cDNA plasmids showed that TORC2 was the most abundant, followed by TORC1 and TORC3 (2.0 × 10−14, 9.2 × 10−14, and 6.9 × 10−15 mol/μg RNA, respectively).

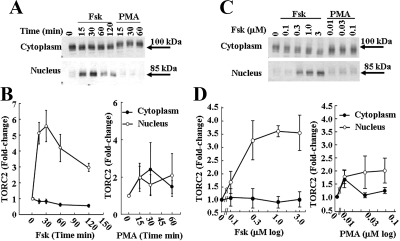

The ability of the adenylate cyclase activator, forskolin, and the PKC activator, PMA, to induce nuclear translocation of TORC2 was examined by Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins. The time course of the effect of 3 μm forskolin and 0.1 μm PMA are shown in Fig. 1, A and B. In basal conditions, there was doublet with a prominent band of about 100 kDa and a weaker band of about 85 kDa in the cytoplasm. These bands were also detectable in the nucleus but its intensity was weak. Incubation with forskolin decreased the intensity of the upper portion of the cytoplasmic TORC2 band, whereas causing a time-dependent increase of the lower the nuclear TORC2 band. Nuclear translocation was maximal at 30 min and started to decline by 60 min. In contrast to forskolin, PMA had little effect on nuclear TORC2 and slightly delayed the migration of the cytoplasmic band to about 105 kDa. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between forskolin and PMA responses (P < 0.01, F = 23, n = 4).

Figure 1.

Time course (A and B) and dose response (C and D) of the effect of forskolin and PMA on nuclear translocation of TORC2 in 4B cells Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins from cells treated with vehicle (0.01% DMSO for time and concentration 0), forskolin (Fsk), or PMA were subjected to Western blot analysis for TORC2. Data points are the mean ± se of the values obtained in three experiments, expressed as fold-change from basal values in vehicle treated cells (time 0 in B). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between time-dependent effects of forskolin and PMA in the nucleus (n = 3, P < 0.01, F = 21.4). Using one-way ANOVA (different concentration range impaired two-way analysis) concentration dependence was significant for forskolin (n = 3, P < 0.01, F = 6.0, n = 3) but not of PMA (n = 3, P = 0.3, F = 1.5).

The changes in TORC2 levels in the cytoplasm and nucleus were dependent on the concentration of forskolin (Fig. 1, C and D). In the cytoplasm, levels tended to decrease with the higher doses. TORC2 levels in the nucleus increased with 0.1 μm forskolin reached maximum with 0.3 μm and remained at similar levels up to 3 μm. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant concentration effect of forskolin (P < 0.01, F = 5.9, n = 3). Consistent with the findings in the time course, PMA had no significant effect on nuclear levels of TORC2 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.3, F = 1.5) (Fig. 1, C and D).

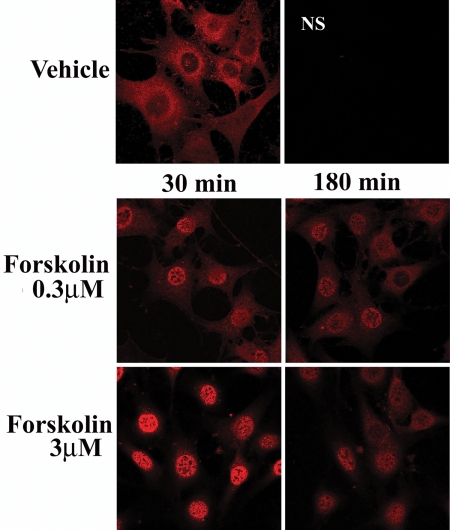

These effects of forskolin on TORC2 were confirmed by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Fig. 2, TORC2 staining is predominantly in the cytoplasm. Incubation with 0.3 μm forskolin clearly increased immunofluorescence in the nucleus and decreased it in the cytoplasm, an effect which was much more marked with the high forskolin concentration (3 μm). By 3 h, TORC2 immunofluorescence was still present in the nucleus but its intensity had clearly declined (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forskolin induces transient translocation of TORC2 to the nucleus Cells were treated with vehicle (0.01% DMSO), forskolin (0.3 or 3 μm) for 30 min or 3 h before fixation and visualization of endogenous TORC2 by immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy at ×63 magnification. Negative controls were processed in the absence of TORC antibody. NS, nonspecific in the absence of primary anibody.

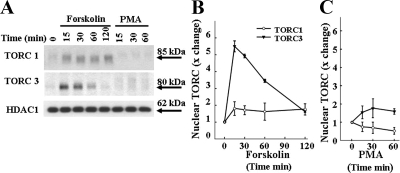

Effect of forskolin and PMA on nuclear translocation of TORC1 and TORC3

Western blot analysis using antibodies against TORC1 and TORC3 revealed specific bands of molecular mass 85 and 80 kDa, respectively, in nucleus (Fig. 3A). The molecular size of the bands was higher (∼100 kDa) in the cytoplasm (data not shown). Forskolin induced an about 2-fold increase in nuclear TORC1. As shown in the pooled data from three experiments (Fig. 3B), the increases in nuclear TORC1 with forskolin were sustained up to the 2-h time point (P < 0.001 compared with PMA). Forskolin also caused a rapid increase of TORC3 levels in the nucleus. Levels were already maximal at 15 min and declined, having returned to basal levels by 2 h (P < 0.01 compared with PMA). As shown for TORC2 in Fig. 1, PMA had no effect on nuclear levels of TORC1 and TORC3 (Fig. 3C) and delayed the migration of the bands in the cytoplasm (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Time course of the effect of forskolin and PMA on nuclear TORC1 and TORC3 levels Western blot analysis for TORC1 and TORC3 in the same nuclear proteins from cells treated with forskolin (A and B) or PMA (A and C) shown in Fig. 1B. Data points are the mean ± se of the values obtained in three experiments, expressed as fold-change from basal values (time 0, incubated with vehicle, DMSO 0.01%). Western blot images from a representative experiment are shown in A. The time of film exposure required to visualize the TORC bands were 5–10 sec for TORC2 and 10–30 min for TORC1 and TORC3. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time with forskolin compared with PMA, P < 0.001, F = 32.4, for TORC1, and P < 0.001, F = 25.0, for TORC3, n = 3).

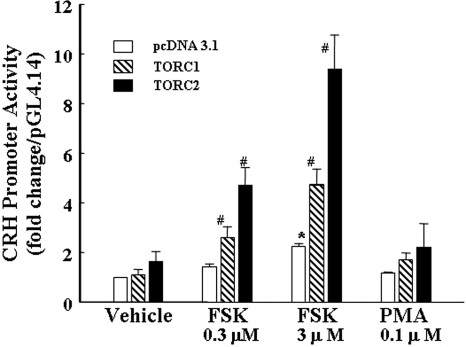

TORC overexpression potentiates forskolin-stimulated CRH promoter activity

To determine the ability of TORC to influence CRH transcription, 4B cells were cotransfected with the rat CRH promoter reporter, pGL4-CRHp, and expression vectors for TORC1 and TORC2. As shown in Fig. 4, 0.3 and 3 μm forskolin increased CRH promoter activity by 1.4- and 2.4-fold, respectively. As indicated in Materials and Methods, pGL4-CRHp had to be used to avoid nonspecific luciferase activation by cotransfection with the expression vector, as observed for pGL3 basic. Cotransfection of neither TORC1 nor TORC2 had any significant effect on basal CRH promoter activity, although TORC2 tended to increase it. On the other hand, cotransfection of TORC1 or TORC2 enhanced the stimulatory effect of 0.3 μm forskolin by 2.6- and 4.7-fold, respectively, and 3 μm forskolin by 4.4- and 9.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

TORC overexpression potentiates forskolin stimulated CRH promoter activity cells were cotransfected with the expression vector, pcDNA 3.1, empty or containing TORC1 or TORC2 and the CRH promoter reporter construct, CRHp-pGL4 or empty pGL4–14.1, 18 h before stimulation with forskolin or PMA for 6 h before and measurement of luciferase activity. Bars represent the mean ± se of the data obtained in three experiments. *, P < 0.01 vs. pcDNA 3.1-transfected basal (vehicle, 0.01% DMSO); #, P < 0.01 compared with the respective forskolin-stimulated pcDNA 3.1.

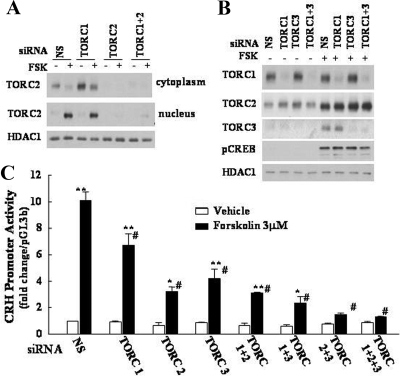

Effect of siRNA TORC knockout on CRH promoter activity in 4B cells

The role of endogenous TORCs on cyclic AMP-dependent activation of the CRH transcription was examined in 4B cells 18 h after cotransfection of CRHp-Luc and TORC siRNAs. As shown in Fig. 5A, Western blot analysis for TORC2 in cells transfected with a nonspecific oligonucleotide, or TORC1 siRNA, revealed the expected TORC2 band in the cytoplasm and nuclear translocation after 20-min incubation with forskolin. On the other hand, TORC2 siRNA transfection caused a marked decrease in TORC2 levels to almost undetectable levels. Similarly, TORC1 and TORC3 siRNAs blocked expression of the respective TORC in nucleus but not that of heterologous TORCs (Fig. 5B). Neither TORC1, TORC2, nor TORC3 siRNA had any effect on the levels of histone deacetylase 1 or phosho-CREB in the nucleus.

Figure 5.

Silencing RNA blockade of specific TORC subtypes blunts CRH promoter activity Effect of siRNA blockade of endogenous TORC2 (A) or TORC1 and TORC3 (B) protein levels (A) or CRH promoter activity (C). A, 4B cells cotransfected with CRHp-luc and a nonspecific (NS), TORC1, or TORC2 siRNA, or their combination, were incubated for 20 min with forskolin (FSK) before preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts for Western blot analysis. C, Cotransfected cells were incubated for 6 h with forskolin or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) before measurement of luciferase activity. Bars are the mean ± se of data obtained in three separate experiments, expressed as fold-change from basal in cells transfected with the nonspecific oligonucleotide. **, P < 0.001 forskolin vs. respective basal; *, P < 0.03 forskolin vs. respective basal; #, P < 0.001 vs. forskolin, nonspecific oligonucleotide.

The consequence of blocking TORC production on CRH promoter activity is shown in Fig. 5C. Cotransfection with TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 siRNA had no effect on basal CRH promoter activity. However, all three TORC siRNA had a partial inhibitory effect of forskolin-stimulated CRH promoter activity, with TORC2 siRNA being the most effective (76.3% inhibition). TORC1 siRNA and TORC3 siRNA reduced CRH promoter activity by 54.9 and 66.2%, respectively. TORC1 siRNA had no significant effect on the inhibition by TORC2 siRNA and slightly enhanced the inhibition by TORC3 siRNA. On the other hand, combined blockade of TORC2 and TORC3 or TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3 caused almost complete inhibition of forskolin-stimulated CRH promoter activity, with 96.7 and 98.3% inhibition, respectively.

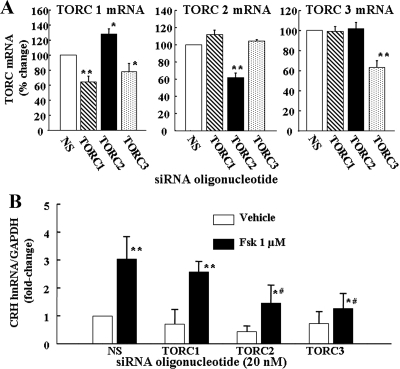

Effect of siRNA TORC blockade on forskolin-induced CRH hnRNA

To determine whether TORC is required for driving endogenous CRH transcription, primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons were transfected with TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 siRNA for 24 h before measuring TORC mRNA (to assess blocking effectiveness) and forskolin-induced CRH hnRNA. As shown in Fig. 6A, transfection of TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 siRNA in primary hypothalamic neuron cultures reduced TORC mRNA levels by 37% (P < 0.01), 38% (P < 0.001), and 37% (P < 0.001), respectively, compared with levels in neurons transfected with nonspecific oligonucleotide. TORC2 and TORC3 siRNA transfection had no effect on mRNA levels of heterologous TORCs in hypothalamic neurons. However, TORC1 siRNA also reduced TORC3 mRNA levels (35%, P < 0.01) and significantly increased TORC2 mRNA levels (28%, P < 0.02) (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Silencing RNA blockade of specific TORC subtypes reduces forkolin-stimulated CRH transcription in CRH neurons Effect of siRNA blockade of endogenous TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 on the different TORC subtype mRNA levels (A) or CRH hnRNA levels in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons (B). Neuronal cultures were transfected with a nonspecific (NS), or TORC1, TORC2, or TORC3 siRNA, and 24 h later incubated for 45 min with forskolin (Fsk) or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) before preparation of total RNA for determination of TORC mRNA and CRH hnRNA by qRT-PCR. Bars are the mean ± se of data obtained in four experiments, expressed as percent change from cells transfected with NS (for TORC mRNA) or fold-change from vehicle in cells transfected with NS. **, P < 0.001 siRNA vs. NS (TORC mRNA), or forskolin vs. respective vehicle (CRH hnRNA); *, P < 0.01 siRNA vs. NS (TORC mRNA), or P < 0.03 forskolin vs. respective vehicle (CRH hnRNA); #, P < 0.001 forskolin siRNA vs. forskolin nonspecific oligonucleotide.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of CRH hnRNA of primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons transfected with TORC siRNA revealed no significant effect of TORC1 siRNA on basal or forskolin-induced CRH hnRNA levels. In contrast, TORC2 siRNA reduced forskolin mRNA levels by 51% (P < 0.001) and tended to decrease basal levels. TORC3 siRNA was equally effective, reducing forskolin-stimulated CRH hnRNA by 59% (P < 0.001) compared with neurons transfected with nonspecific oligonucleotide (Fig. 6B).

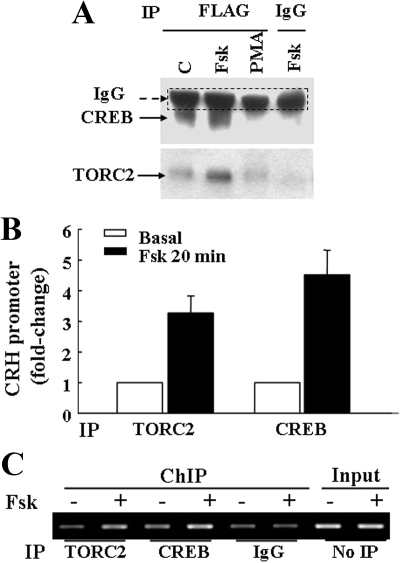

Forskolin induces association between TORC and CREB in the nucleus

The possibility of physical association between TORC2 and CREB in the nucleus of 4B cells after forskolin treatment was examined by coimmunoprecipitation. Preliminary experiments showed little recovery of endogenous TORC protein after immunoprecipitation using a number of anti-TORC2 antibodies (Calbiochem, Cell Signaling, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Similarly, attempts to immunoprecipitate with CREB antibodies failed because of not specific bands which interfered with the immunodetection of TORC. For this reason, cells were transfected with an expression vector for TORC harboring FLAG epitope 24 h before treatment with forskolin or PMA and immunoprecipitation of nuclear proteins with anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot analysis using an anti-CREB antibody in complexes immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody revealed a 43-kDa band corresponding to the molecular size of CREB. The intensity of this band increased markedly in nuclear proteins from forskolin treated cells compared with control. In contrast, in nuclear proteins from cells treated with PMA, no CREB band was observed after immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody. There was no CREB detected in forskolin treated sample after immunoprecipitation with IgG (Fig. 7). Western blot analysis of the same blots using an anti-TORC2 antibody revealed the expected band on about 90 kDa corresponding to the molecular size of the TORC/FLAG fusion protein. As for the changes in FLAG-immunoprecipitated CREB, the intensity of the TORC2 band increased after incubation of the cells with forskolin but not with PMA (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Forskolin induces association of CREB and TORC in the nucleus and TORC recruitment by the CRH promoter (A) 4B cells transfected with TORC/FLAG fusion constructs 18 h earlier, were incubated with forskolin (Fsk) or PMA for 20 min before preparation of nuclear extracts and immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot analysis of the FLAG immunoprecipitates revealed an increase in coimmunoprecipitation of CREB and TORC2 in nuclear proteins from cells treated with forskolin but not with PMA. A nonspecific immunoglobulin band present just above the CREB band is demarcated by the dashed line. B and C, ChIP assay of CRH promoter DNA using anti-TORC2 and CREB antibodies. 4B cells transfected with the CRH promoter-luciferase construct 18 h earlier were incubated with or without forskolin (Fsk) for 20 min before DNA cross-linking and ChIP assay. B, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of CRH promoter after immunoprecipitation using anti-TORC2 and CREB antibodies. Bars are the mean ± se of data from four experiments, after subtracting nonspecific values obtained after immunoprecipitation with antirabbit IgG. C, Gel analysis of the PCR product for the CRH promoter in a representative experiment.

Forskolin induces TORC2 recruitment by the CRH promoter

The ability of TORC2 to bind the CRH promoter was examined by ChIP assays in 4B cells transfected with the CRH promoter-luciferase construct. Quantitative RT-PCR of the CRH promoter in chromatin from 4B cells incubated with vehicle revealed levels of CRH promoter almost undistinguishable from those after immunoprecipitation with nonimmune IgG. In three experiments, incubation of the cells with forskolin (20 min) increased the amount of CRH promoter immunoprecipitated using anti-TORC2 or anti-CREB antibodies by 3.3- and 4.6-fold, respectively (Fig. 7B). Gel analysis of the PCR product for the CRH promoter in a representative experiment is shown in Fig. 7C.

Discussion

The recent demonstration that phospho-CREB is required but not sufficient for activation of CRH transcription strongly suggested that a coactivator is required (15). The present study using the hypothalamic cell line 4B and primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons provides strong evidence that translocation of the CREB coactivator, TORC, to the nucleus, and its interaction with CREB at the level of the CRH promoter is required for initiation of CRH transcription. CRH expression in 4B cells is insufficient to study endogenous expression, but the cell line has proven useful for studying CRH transcription using reporter gene assays. All three TORC subtypes are expressed in 4B cells, but TORC2 appears to be the predominant species, as shown by the clearly higher TORC2 mRNA levels compared with those for TORC1 and TORC3. The TORC subtypes expressed in CRH neurons are under current investigation in our laboratory, but it is clear from ongoing immunohistochemical studies that TORC2 is present and that it undergoes nuclear translocation during stress (21).

The first supporting evidence of a role for TORC in the activation of CRH transcription is the correlation between the effect of forskolin and PMA on the intracellular distribution of TORC shown by this study and the reported activity of these compounds to activate the CRH promoter (15,22). TORC phosphorylation by specific kinases such as salt inducible kinase (SIK) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) increases its affinity with the scaffolding protein 14-3-3; thus, preventing nuclear translocation (17). Cyclic AMP/PKA signaling inactivates SIK and AMPK, leading to TORC dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Consistent with previous studies, PMA alone did not stimulate CRH promoter activity, in spite of its ability to induce phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of CREB (15). The present demonstration by Western blot analysis that PMA causes sequestration of TORC in the cytoplasm could explain the lack of effect of PMA on CRH transcription. Because it has been shown that TORC2 phosphorylation alters its migration pattern in the gel (23), the present demonstration that delayed migration of the TORC band in the cytoplasm of cells treated with PMA suggests that PMA induces hyperphosphorylation of TORC. A weak higher molecular size band was also apparent in some Western blot analyses on nuclear proteins of PMA treated cells. Because SIK and AMPK can translocate to the nucleus leading to TORC phosphorylation and its export to the cytoplasm (24), the finding of phosphorylated TORC in the nucleus is not unexpected. However, minor contamination of nuclear protein preparations with cytoplasmatic proteins cannot be ruled out. It is noteworthy that while PMA sequesters TORC in the cytoplasm, it has been shown to synergize with forskolin in stimulating CRH transcription (15). In this regard, ongoing studies show that PMA reduces but does not prevent forskolin-induced TORC translocation to the nucleus (Liu, Y. and G. Aguilera, unpublished data). This suggests that cyclic AMP can overcome the inhibitory effect of PMA allowing nuclear translocation of TORC and activation of CRH transcription. The exact mechanism of the synergistic effect of PMA and forskolin on CRH transcription remains to be elucidated but it appears to involve signaling interaction at levels other than TORC translocation.

A second line of evidence that TORC is involved in the activation of the CRH promoter was provided by the ability of TORC1 or TORC2 overexpression to potentiate and TORC siRNA blockade to reduce the stimulatory effect of forskolin on CRH transcription. A similar potentiating effect of TORC overexpression on cyclic AMP-stimulated gene expression has been reported for other genes in which transcriptional activation depends on TORC. This includes the StAR gene (24), the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeats (25), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (16). Only TORC2 overexpression increased basal CRH promoter activity, supporting the possibility that at least in 4B cells TORC2 is the main subtype involved regulating CRH transcription. The fact that TORC overexpression did not facilitate CRH transcription in cells incubated with PMA was not unexpected because PMA appeared to cause hyperphosphorylation of TORC and its sequestration in the cytoplasm (as shown by the Western blot analysis). In addition, the time course of phospho-CREB production by PMA showed an increase less sustained than that after incubation of the cells with forskolin. Thus, it is not possible to rule out that the much more transient increase in phospho-CREB levels in the nucleus after PMA exposure contributes to the lack of effect of PMA on CRH transcription.

The most compelling evidence that TORC is important for CRH transcription was provided by the blunting effect of knocking down endogenous TORC on forskolin-stimulated CRH promoter activity in 4B cells and CRH hnRNA in primary neuronal cultures. In spite of the lower effectiveness of siRNA blockade in neuronal cultures, TORC2 and TORC3 siRNA transfection significantly reduced forskolin-stimulated endogenous CRH hnRNA. Because TORC3 siRNA was as effective as TORC2 siRNA in reducing CRH hnRNA, the lack of effect of TORC1 siRNA (which also reduced TORC3 mRNA) on forskolin-stimulated CRH hnRNA was intriguing. Although a nonspecific effect of TORC1 siRNA cannot be ruled out, it is likely that an increase in TORC2 (as suggested by the increase in mRNA) compensates for the lack of TORC3.

Although first identified as a CREB coactivator necessary for transcriptional activation of gluconeogenic enzymes (17), it is now established that TORC is required for transcriptional regulation of several CREB inducible genes. These include Star protein, amphiregulin, hepatic leukemia factor, regulator of G protein-coupled receptor 2, and nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 (18,24,25). TORC is well recognized as a specific CREB coactivator (17,25,26). However, recent studies have shown association of TORC with other transcription factors such as the homeobox protein MEIS1A in the transcriptional regulation of Hoxb2 and Meis1 independently of CREB (27). In the case of CRH, TORC most likely acts as a CREB coactivator. First, we and others have established that CREB is not only involved but it is required for stimulation of CRH transcription. As shown by this study and previous reports, levels of CREB bound to the CRH promoter are very low in basal conditions, but recruitment clearly increases during transcriptional activation of the CRH gene in vivo and in vitro (13,20,28). Secondly, we previously reported dramatic reductions in cyclic-AMP-stimulated CRH promoter activity after transfection of the CREB dominant negative, A-CREB. The present demonstration that CREB coimmunoprecipitates with TORC2 in nuclear extracts from 4B cells incubated with forskolin indicated that there is physical interaction between the two proteins. Because the experiments were performed on transfected cells, the existence of nonspecific interaction due to overexpression cannot be ruled out. However, this is unlikely because anti-FLAG-immunoprecipitation of nuclear proteins of cells treated with PMA did not yield CREB or TORC bands in the Western blot analysis. The present ChIP assay data showing recruitment of both TORC2 and CREB by the CRH promoter suggest an interaction between TORC and the CRH promoter. Such an interaction could occur directly with the DNA or indirectly through protein-protein interaction with CREB or other protein in the transcriptional complex. Although further studies are needed to demonstrate an interaction of TORC with the endogenous CRH promoter, these data support the hypothesis that TORC acts as the CREB coactivator required for activation of CRH transcription.

The mechanism regulating TORC phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of TORC in 4B cells is under current investigation. Two major kinases responsible for TORC phosphorylation, AMPK and SIK, have been identified (18,29,30,31). In addition, the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin, dephosphorylates TORC, facilitating its nuclear translocation (18,31). The marked effects of the cyclic AMP stimulator forskolin on TORC translocation in 4B cells suggest that cyclic AMP plays a role. In this regard, it has been shown that inactivation of both AMPK and SIK can occur through PKA-dependent phosphorylation (17,29,30,31). Also, increases in cytoplasmic calcium secondary to PKA-dependent phosphorylation of calcium channels could contribute to TORC activation by activating calcineurin (32). Which one of these mechanisms participates in the activation of TORC and CRH transcription remains to be elucidated.

In summary, this study provides strong evidence that the CREB coactivator, TORC, mainly TORC2, acts as the required coactivator for activation of CRH transcription. This conclusion is supported by 1) the good correlation between TORC translocation to the nucleus and activation of CRH transcription, 2) the finding that TORC overexpression potentiates forskolin-stimulated CRH transcription, 3) the inhibitory effect of endogenous TORC blockade on forskolin stimulated CRH transcription, and 4) the ability of the CRH promoter to recruit TORC during activation of CRH transcription. The data provide novel insights on the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the transcriptional regulation of the CRH gene.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marc Montminy (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) for providing the expression vectors for TORC1 and TORC2.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Intramural Research program of the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 15, 2010

For editorial see page 855

Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ChIP, chromatin immuprecipitation; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; CRHp, CRH promoter-driven; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; hnRNA, heteronuclear RNA; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol ester 12-myristate 13-acetate; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; SIK, salt-inducible kinase; siRNA, silencing RNA; TORC, transducer of regulated CREB activity.

References

- Aguilera G 1994 Regulation of pituitary ACTH secretion during chronic stress. Front Neuroendocrinol 15:321–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Levin N, Walker C-D, Bradbury MJ, Suemaru S, Scribner KS 1994 Corticosteroids and the control of function in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Ann NY Acad Sci 746:22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A, Naray-Fejes-Toth A 1994 Glucocorticoids and stress: permissive and suppressive actions. Ann NY Acad Sci 746:115–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Goodyer IM, Grossman AB, Hastings MH, de Kloet ER, Lightman SL, Lupien SJ, Roozendaal B, Seckl JR 2006 Do corticosteroids damage the brain? J Neuroendocrinol 18:393–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Brinton RE, Sapolsky RM 1988 Glucocorticoid receptors and behavior: implications for the stress response. Adv Exp Med Biol 245:35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G, Nikodemova M, Wynn PC, Catt KJ 2004 Corticotropin releasing hormone receptors: two decades later. Peptides 25:319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Vale WW 2004 CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44:525–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G 1998 Corticotropin releasing hormone, receptor regulation and the stress response. TEM 9:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Schafer MK, Thompson RC, Watson SJ 1992 Rapid regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene transcription in vivo. Mol Endocrinol 6:1061–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Levy A, Lightman SL 1997 Rapid changes in heteronuclear RNA for corticotrophin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin in response to acute stress. J Endocrinol 152:81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodemova M, Kasckow J, Liu H, Manganiello V, Aguilera G 2003 Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity in AtT-20 cells and in a transformed hypothalamic cell line. Endocrinology 144:1292–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seasholtz AF, Thompson RC, Douglass JO 1988 Identification of a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive element in the rat corticotropin-releasing hormone gene. Mol Endocrinol 2:1311–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfl S, Martinez C, Majzoub JA 1999 Inducible binding of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP)-responsive element binding protein (CREB) to a cAMP-responsive promoter in vivo. Mol Endocrinol 13:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Tsien RW 2002 Dynamic multiphosphorylation passwords for activity-dependent gene expression. Neuron 34:179–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kamitakahara A, Kim A, Aguilera G 2008 Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate responsive element binding protein phosphorylation is required but not sufficient for activation of corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription. Endocrinology 149:3512–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoi K, Horiba N, Tozawa F, Sakai Y, Sakai K, Abe K, Demura H, Suda T 1996 Major role of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A pathway in corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression in the rat hypothalamus in vivo. Endocrinology 137:2389–2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Screaton R, Guzman E, Miraglia L, Hogenesch JB, Montminy M 2003 TORCs: transducers of regulated CREB activity. Molecular Cell 12:413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Kasper LH, Lerach S, Jeevan T, Brindle PK 2007 Individual CREB-target genes dictate usage of distinct cAMP-responsive coactivation mechanisms. EMBO J 26:2890–2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentin R, Liu Y, Koo SH, Hedrick S, Vargas T, Heredia J, Yates J, Montminy M 2007 Insulin modulates gluconeogenesis by inhibition of the coactivator TORC2. Nature 449:366–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kalintchenko N, Sassone-Corsi P, Aguilera G 2006 Inhibition of corticotrophin-releasing hormone transcription by inducible cAMP-early repressor in the hypothalamic cell line, 4B. J Neuroendocrinol 18:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Knobloch S, Grinevich V, Aguilera G 2009 Stress induces nuclear translocation of the CREB co-activator, transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC) in corticotropin releasing hormone neurons. 91th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Washington, DC, 2009 (Abstract P2-636) [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Aguilera G 2009 Cyclic AMP inducible early repressor mediates the termination of corticotropin releasing hormone transcription in hypothalamic neurons. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29:1275–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Goode J, Best J, Meltzer J, Schilman PE, Chen J, Garza D, Thomas JB, Montminy M 2008 The insulin-regulated CREB coactivator TORC promotes stress resistance in Drosophila. Cell Metabolism 7:434–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori H, Kanematsu M, Kajimura J, Hatano O, Katoh Y, Lin XZ, Min L, Yamazaki T, Doi J, Okamoto M 2007 Dephosphorylation of TORC initiates expression of the StAR gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 265–266:196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu YT, Chin KT, Siu KL, Yee Wai Choy E, Jeang KT, Jin DY 2006 TORC1 and TORC2 coacivators are required for tax activation of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeats. J Virol 80:7052–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iourgenko V, Zhang W, Mickanin C, Daly I, Jiang C, Hexham JM, Orth AP, Miraglia L, Meltzer J, Garza D, Chirn GW, McWhinnie E, Cohen D, Skelton J, Terry R, Yu Y, Bodian D, Buxton FP, Zhu J, Song C, Labow MA 2003 Identification of a family of cAMP response element-binding protein coactivators by genome-scale functional analysis in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Scie USA 100:12147–12152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh S, Looi Y, Shen H, Fang J, Bodner C, Houle M, Ng A-H, Screaton RA, Featherstone M 2009 Transcriptional activation by MEIS1A in response to protein kinase A signaling requires the transducers of regulated CREB family of CREB co-activators. J Biol Chem 284:18904–18912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JD, Liu Y, Sassone-Corsi P, Aguilera G 2005 Role of glucocorticoids and cAMP-mediated repression in limiting corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription during stress. J Neurosci 25:4073–4081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson DS, Summers RJ, Bengtsson T 2008 Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase activity by G-protein coupled receptors: potential utility in treatment of diabetes and heart disease. Pharmacol Ther 119:291–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori H, Okamoto M 2008 Regulation of CREB-mediated gene expression by salt inducible kinase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 108:287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittinger MA, McWhinnie E, Meltzer J, Iourgenko V, Latario B, Liu X, Chen C, Song C, Garza D, Labow M 2004 Activation of cAMP response element-mediated gene expression by regulated nuclear transport of TORC proteins. Curr Biol 14:2156–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh KS, Murphy BJ, Colvin AA, Hell JW, Takahashi M, Catterall WA 1996 Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full-length form of the α-1 subunit of the cardiac L-type calcium channel by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry 35:10392–10402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]