Abstract

Follistatin (FST) is a natural antagonist of activin and related TGFβ superfamily ligands that exists as three protein isoforms differing in length at the C terminus. The longest FST315 isoform is found in the circulation, whereas the shortest FST288 isoform is typically found in or on cells and tissues, and the intermediate FST303 isoform is found in gonads. We recently demonstrated that the FST isoforms have distinct biological actions in vitro that, taken together with the differential distribution, suggests they may also have different roles in vivo. To explore the specific role of individual FST isoforms, we created a single-isoform FST288-only mouse. In contrast to the neonatal death of FST global knockout mice, FST288-only mice survive to adulthood. Although they appear normal, FST288-only mice have fertility defects including reduced litter size and frequency. Follicles were counted in ovaries from 8.5- to 400-d-old females. Significantly fewer morphologically healthy antral follicles were found in 100- to 250-d FST288-only ovaries, but there were significantly more secondary, primary, and primordial follicles detected at d 8.5 in FST288-only ovaries. However, depletion of this primordial follicle pool is more rapid in FST288-only females resulting in a deficit by 250 d of age and early cessation of reproduction. Superovulated FST288-only females have fewer ovulated eggs and embryos. These results indicate that the FST isoforms have different activities in vivo, that the FST288-only isoform is sufficient for development, and that loss of FST303 and FST315 isoforms results in fertility defects that resemble activin hyperactivity and premature ovarian failure.

The FST288 isoform is sufficient for survival but results in female fertility defects resembling premature ovarian failure due to more rapid depletion of primordial follicles.

Although follistatin (FST) was originally discovered as a gonadal protein that bound and neutralized the TGFβ superfamily member activin with high affinity, subsequent investigation revealed that FST is actually produced in many tissues where activin is synthesized, suggesting a primarily autocrine/paracrine mechanism of action (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2). Two alternatively spliced mRNAs are produced from the single Fst gene, and the protein product of the primary mRNA transcript is posttranslationally processed at its C terminus, creating a total of three protein isoforms that differ in the length of exon 6 preserved at the C terminus, with FST288 having no exon 6 sequence, FST303 about half, and FST315 containing all of exon 6 (3,4). The length of exon 6 determines the activity of the heparin-binding sequence within FST domain 1 such that FST288 binds tightly, FST303 partially, and FST315 hardly at all to cell surface heparin-sulfated proteoglycans (3,5). We recently demonstrated that these biochemical differences translate into altered biological actions that can be detected in vitro with FST288 having the greatest and FST315 the least activin-neutralizing activity when the activin was produced endogenously by cells (6). These observations suggested that the FST288 isoform would be superior to the other isoforms in regulating autocrine-acting (cell-autonomous) activin such as during development or within tissues or organs. On the other hand, FST315 appears to be better suited for endocrine functions of FST consistent with its being the primary isoform in the circulation (7).

In addition to activin, FST isoforms bind other TGFβ family ligands, although with lower affinity. All three FST isoforms bind myostatin and growth differentiation factor 11 with 3- to 5-fold lower affinity relative to activin, whereas bone morphogenetic proteins 6 and 7 binding being about 2-fold lower than myostatin, results that agreed with neutralization of in vitro biological activity (6). These results suggest that in vivo, FST likely regulates important physiological systems during development driven by a variety of TGFβ superfamily members, a deduction supported by the fact that global FST deletion leads to early neonatal lethality in mice due to multiple muscular, skeletal, and other defects (8). Although this early lethality made analysis of adult roles for FST difficult to ascertain, deletion of FST in adult granulosa cells was found to significantly reduce fertility through altered follicle and oocyte maturation, leading to reduced fecundity and early termination of ovarian activity (9), similar to some aspects of human premature ovarian failure. Although this study demonstrates the importance of FST activity to adult reproductive physiology, at least in females, it does not address the role of specific FST isoforms in vivo. Recently, human FST288 or -315 cDNAs were used to rescue FST knockout (KO) mice, demonstrating isoform-specific actions for FST expressed under control of the human FST promoter (10), a finding consistent with FST isoforms having unique actions in vivo.

Although activin was originally purified from ovarian follicular fluid and thought to be important for female reproduction, its precise roles in follicle development have been difficult to ascertain. Deletion of activin production in granulosa cells leads to defects in follicle development and an overabundance of corpora lutea collectively resulting in subfertility, the severity of which increases with decreasing activin allele dosage (11). Activin also has an important role in formation of primordial follicles during germ cell nest breakdown because activin administration during early neonatal development resulted in a 27% increase in primordial follicle number on postnatal d 6, although this excess in primordial follicle pool size was no longer present at puberty (12). Taken together with mouse models of altered FST production, these studies collectively indicate that activin bioactivity, as regulated by FST, is critical both for neonatal follicle formation during development and for maturation in adults.

To explore possible isoform-specific activities in the context of the endogenous mouse Fst gene, we deleted the alternative splice acceptor region of intron 5 using a knock-in strategy. This created a mouse in which only the FST288 isoform was produced under the control of the endogenous mouse Fst promoter (FST288-only mice). We hypothesized that the biochemical properties of FST288 that allow binding to cell surface proteoglycans would be well suited to developmental functions of Fst, permitting evaluation of isoform-specific roles in adults. We now report that FST288-only mice survive to adulthood, have none of the phenotypes associated with FST-null mice, but have reduced litter size and overall fecundity similar to the granulosa cell-specific FST KO mice. In addition, FST288-only mice are born with a larger initial primordial follicle pool that declines more rapidly than wild-type (WT) mice and is thus smaller throughout most of their adult life. These results indicate that the FST288 isoform itself is sufficient for embryonic and neonatal development but not for normal reproduction. In addition, the larger initial primordial follicle pool, more rapid decline in this pool, and premature reduction or cessation of reproduction are consistent with the hypothesis that normal ovarian activity is dependent on the size of the primordial follicle pool and eventually ceases when this pool falls below a critical threshold (13).

Materials and Methods

Generation of FST288-only mice

We first attempted to create a FST303-only single-isoform mouse, reasoning that its partial heparin-binding activity would allow it to fulfill many of the known FST functions. Thus, our knock-in construct was designed to remove the alternative splicing acceptor site in intron 5 and insert a stop codon immediately downstream of Gln303. This targeting construct contained 5.66 kb Fst gene upstream sequence and 5.72 kb downstream sequence for homologous recombination. A short DNA segment of intron 5 where the alternative splice rejoins the mRNA after splicing (−68/+38 bp relative to the alternative donor site) was removed and replaced with a Neo cassette containing two loxP sites (see supplemental Fig. 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). The stop codon after Gln303 was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using QuikChange (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). As detailed in Results, these mice actually produce only the FST288 transcript and are thus called FST288-only mice. Genotyping primers are listed in supplemental Table 1. All procedures used to breed and analyze these mice were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital’s and Baystate Medical Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out in accordance with federal and institutional requirements.

Analysis of Fst gene expression

Fst mRNA was extracted from ovaries of mature females using Trizol (Life Technologies, Inc.-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For Northern blots, 15 μg RNA obtained from pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG)-treated females was separated by electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and detected with a radiolabeled probe produced by PCR from the Fst cDNA template. For quantitative mRNA expression analysis, mRNA was extracted from untreated 98-d ovaries and reverse transcribed as previously described (14). Fst, Inhba, Inhbb, SMAD2, and SMAD3 were quantitated by SYBR quantitative PCR (qPCR) (primers listed in supplemental Table 1) using Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) reagents according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Due to persistent background fluorescence when analyzing FSTL3 with multiple primer sets, a TaqMan assay was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and validated using FSTL3 KO RNA (14). A relative standard was created by pooling RNA from ovary, testis, liver, and pancreatic islets, which was reverse transcribed and serially diluted 1:5 to create four standards run in every assay. In addition, RPL19 gene expression was quantitated in each reverse transcription sample as normalization control using the same standard. Expression levels are depicted as expression of a specific gene relative to the internal standard divided by RPL19 expression.

Follicular fluid collection and analysis

Follicular fluid was collected from ovaries of 12- to 14-wk-old mice 44–46 h after ip injection of 5 IU PMSG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with a flame-drawn Pasteur pipette. The follicular fluid from several ovaries was pooled for each genotype, diluted with the distilled water, and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 3 min to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was collected, and the protein concentration was estimated using Quick Start Bradford dye reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and stored at −80 C until analyzed.

To differentiate between different FST protein isoforms and their differentially glycosylated forms, follicular fluid proteins were deglycosylated with N-glycanase (Prozyme kit; San Leandro, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Deglycosylated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE by loading 15 μg from WT and FST288-only mouse follicular fluid samples onto 12% NuPage Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) after reducing with Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad), blocked with 10% dry milk and 0.5% Tween 20 in TBS, and probed with a polyclonal antibody raised to recombinant mouse FST (1:1000) (see validation below). Antibody was detected using peroxidase-conjugated donkey antirabbit IgG (1:60,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and visualized by the Immun-Star horseradish peroxidase detection reagent (Bio-Rad).

Tissue processing and oocyte counting

Ovaries were collected on postnatal d 8.5, 42, 98, 250, and 400, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Oocytes/follicles were counted in every sixth section throughout the entire ovary. For ovaries obtained from neonatal females, oocytes were counted if the nucleus was present in the sections.

Follicles and oocytes were classified according to criteria used by Bristol-Gould et al. (12) with the following exceptions. 1) Primordial follicles were divided into two categories including resting primordial follicles surrounded by only flattened pregranulosa cells and early primary follicles (primordial to primary transition follicles) that have just initiated development and contain some cuboidal granulosa cells. 2) A correction factor was used to determine total oocyte/follicle number for primordial follicles to primary follicles because the oocyte nucleus of primordial and primary follicles was about 6–8 μm and oocytes were counted every sixth 4-μm section, so the counted number of primordial, primordial-to-primary transition, and primary follicles was multiplied by six. Because the nuclear diameter of oocytes in secondary to antral follicles was typically greater than 20 μm, no correction factor was applied to these counts.

Immunohistochemistry for FST in mouse ovary

A polyclonal antibody was raised to recombinant mouse FST315 for these studies. IgG was purified from the serum using protein-A chromatography, and the purified IgG was dialyzed against 10 mm PBS and frozen at 6.1 μg/ml. This antibody recognizes mouse FST but not FSTL3, the most closely related protein (data not shown).

Hydrated sections were treated with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min followed by antigen retrieval for 30 min at 95 C in 10 mm sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.4). After cooling, sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 20 min and blocked with appropriate normal serum provided in the Vectorstain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were incubated in first antibody diluted with blocking buffer (1:9600) overnight at 4 C, rinsed, and then incubated in biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (60 min) and ABC reagent (60 min) (Vector), followed by diaminobenzidine reagent (Vector) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunohistochemical images were obtained with an Olympus BX41 microscope with a Spot Insight color digital camera and Spot Advanced Imaging software. Nonspecific staining was determined by preincubating the FST antibody with excess recombinant FST315 overnight at 4 C.

Superovulation and isolation of embryos/oocyte at 0.5 and 3.5 d

Adult (42–45 d) WT or FST288-only female mice were injected with 5 IU PMSG ip followed 48 h later by administration of 5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (CR121; National Hormone and Pituitary Program, Torrance, CA). After hCG injection, female mice were mated with males of the same genotype and mice with vaginal plugs were killed 22–23 h after hCG. Embryos were recovered from fallopian tubes and counted. In an additional group of mice, uterine horns and fallopian tubes were taken 94 h after hCG injection, and the embryos were recovered and categorized as follows: blastocyst was defined as an embryo consisting of the inner cell mass and a thin trophoblast layer enclosing the blastocoel, morula was a compact embryo between 16- and 64-cell stage, degenerated embryos were one- or two-cell or fragmented embryos.

Statistical analysis

Data comparing reproductive parameters or mRNA expression for WT and FST288-only mice were compared by Student’s t tests or ANOVA using GraphPad Prism. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Generation of FST288-only mice

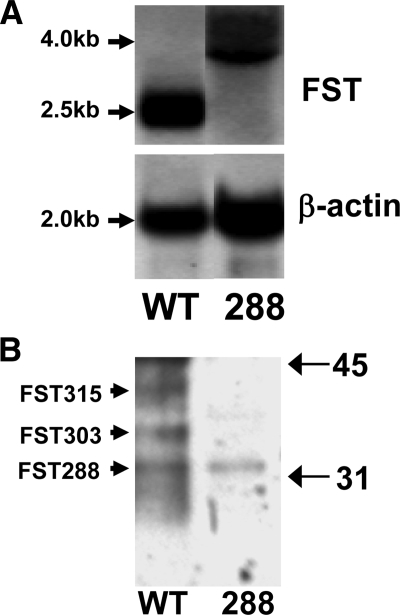

To determine whether the deletion of the splice acceptor site within intron 5 had the desired effect, total Fst expression was analyzed in ovaries from hyperstimulated female WT and FST288-only mice by Northern blotting. As shown in Fig. 1A, the Fst mRNA transcript was substantially larger in FST288-only mice compared with WT littermates and somewhat weaker as well. The larger mRNA transcripts were cloned and sequenced, which demonstrated that the mRNA spliced back into the Neo cassette, adding about 1.5 kb Neo sequence to the 3′ end of the mRNA (see supplemental Fig. 1). However, the sequencing demonstrated that in every clone, this alternate splice produced a stop codon at the end of exon 5 so that only the FST288 protein isoform could be produced from these longer transcripts.

Figure 1.

Analysis of Fst mRNA and protein in the FST288-only mouse. A, Northern blot analysis of RNA from PMSG-treated WT and FST288-only ovaries. WT FST mRNA is at the expected 2.5-kb size, but FST RNA from FST288-only ovaries was 1.5 kb larger (see Materials and Methods and supplemental material for explanation). Note that total FST mRNA is reduced in FST288-only ovaries (stronger β-actin normalization band). B, Western blot analysis of follicular fluid from WT and FST288-only mouse ovaries after deglycosylation. In WT follicular fluid, three bands were detected, corresponding to FST315, FST303, and FST288 (3,27), whereas in follicular fluid from FST288-only females, only the FST288 was detected. This confirms that the genetic modification leads to production of only one FST isoform in FST288-only mice.

To confirm that only the FST288 isoform could be produced, follicular fluid was obtained from WT and FST288-only female mice because it is known to contain high FST concentrations and multiple isoforms in other species (15). After deglycosylation, FST315, -303, and -288 were identified in WT mouse follicular fluid (Fig. 1B, WT). In contrast, only the FST288 isoform could be detected in FST288-only mice (Fig. 1B, lane 288), consistent with the molecular analyses and supporting the conclusion that only the FST288 isoform appears to be synthesized in ovaries of FST288-only mice. Of note, the expression levels of FST288 appear to be similar between FST288-only and WT mouse follicular fluid.

FST protein expression in WT and FST288-only ovaries

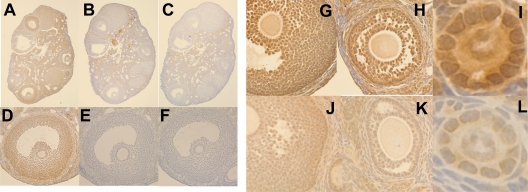

Although FST protein expression has been previously investigated in several species, localization of FST in mouse tissues has been hampered by lack of specific antibodies. We therefore raised a polyclonal antibody to recombinant mouse FST that detected both recombinant mouse FST and natural mouse FST in follicular fluid (Fig. 1B) but did not bind the related mouse FSTL3 (data not shown). Using this antibody, we detected FST in granulosa cells of all follicles including mural granulosa cells of antral follicles, surface epithelium, and some areas of the stroma in ovaries from WT adults (Fig. 2, A and D). When the antibody was preincubated with 10-fold excess mouse FST315, staining within follicles disappeared (Fig. 2, B and E), indicating that this staining was largely specific for FST. When the FST antibody was deleted, staining in stromal tissues persisted at a reduced level, supporting the identification of this staining as nonspecific (Fig. 2, C and F). At higher magnification, FST staining can be seen in oocytes of antral and preantral follicles from WT ovaries as well as in both nuclei and cytoplasm of granulosa cells (Fig. 2, G–I). This staining was substantially reduced but still present in oocytes and granulosa cells from FST288-only ovaries except that the nuclear FST in granulosa cells was substantially weaker or no longer detectable (Fig. 2, J–L). These results suggest that overall FST protein expression is reduced in FST288-only ovaries and that the nuclear staining disappears when the FST303 and FST315 isoforms are deleted.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of FST in WT and FST288-only ovary. FST was localized using a new polyclonal antibody to mouse FST315 in ovarian sections. A, FST staining was observed in oocytes, granulosa cells, parts of stromal cells, and ovarian surface epithelium. Note that nuclear staining was observed in many granulosa cells and oocytes. B, After preincubation of antibody with recombinant FST315, most staining in granulosa cells, oocytes, and surface epithelium is drastically reduced, although some weak staining in stroma remains. C, Even when FST antibody is deleted, some staining remains in the stroma. These results confirm the specificity of this antibody for FST. D–F, Enlargement of preovulatory follicle from A–C, respectively, providing details of cellular localization. G–I, FST staining in WT large antral, small antral, and primary follicle, respectively. J–L, FST staining in similar follicles from FST288-only ovaries. FST staining is much stronger WT ovaries (G–I) compared with FST288-only ovaries (J–L), and the nuclear staining is not observed in FST288-only mice, suggesting that both total amount and intracellular compartmentalization of FST is altered in FST288-only mice.

Expression of Fst and related genes

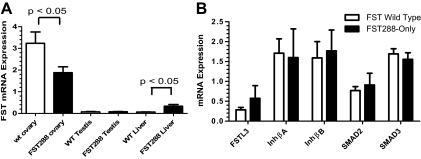

By qPCR, Fst expression mice was reduced by nearly half (P < 0.05) in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT (Fig. 3A). In contrast, there was no difference in Fst expression in testes from adult WT and FST288-only males (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, Fst expression was 5-fold higher in FST288-only liver compared with WT (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). We also examined expression of other genes associated with Fst, including Fstl3, InhβA, InhβB, Smad2, and Smad3, but no differences in ovarian expression between the genotypes were detected (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that FST expression is differentially regulated in ovarian and nonovarian tissues and/or that deletion of the FST315 and FST303 isoforms differentially affects ovaries compared with other tissues. Moreover, deletion of the FST315 and 303 isoforms did not alter expression of other genes in the activin signaling pathway, suggesting that observed phenotypic effects are due to increased ligand action when the expression of FST isoforms is altered.

Figure 3.

Analysis of Fst mRNA expression in WT and FST288-only mice using qPCR. A, Fst mRNA expression was reduced by about half in FST288-only ovaries (black bars) compared with WT ovaries (white bars). However, Fst expression in FST288-only testis is not different from WT testis. In contrast, Fst expression in FST288-only liver is about 4-fold greater than WT liver (n = 4–6 samples for each tissue type). B, Ovarian expression of Fst-related genes (Fstl3) or genes in the activin signaling pathway (activin A, activin B, SMAD2, and SMAD3) are not altered in FST288-only mice compared with WT mice. These results suggest that Fst expression is differentially regulated in different tissues, but expression of genes in the activin signaling pathway are not altered in ovaries.

FST288-only females are subfertile

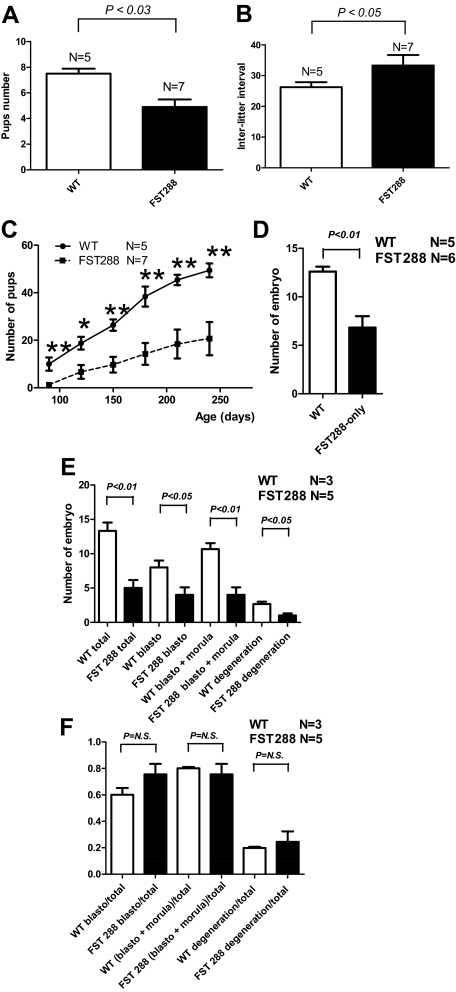

Survival of FST288-only mice to adulthood, as opposed to the neonatal lethality of the global FST KO mouse, allowed examination of the effects of altered FST isoform expression on fertility and ovarian physiology. Litter size and frequency were monitored in five FST WT and seven FST288-only breeding pairs for 8 months. Litter size was significantly reduced by 25% in FST288-only mice, and the interval between litters was significantly longer leading to an overall reduction in cumulative fertility that increased with age in the FST288-only breeders (Fig. 4, A–C). These results suggest that both ovarian physiology (litter size) and neuroendocrine regulation of estrous cycle dynamics (inter-litter interval) were altered by deletion of the FST303 and -315 isoforms.

Figure 4.

Reproductive phenotype of FST288-only females. A, Over an 8-month breeding period, FST288-only females have significantly smaller litters (black bar) compared with WT females mated with males of the same genotype (n = 7 and 5, respectively). B, The mean interval between litters was significantly longer in FST288-only females compared with WT females. C, Analysis of cumulative number of pups for each genotype for all breeding females. Due to smaller litters and longer intervals, the total number of pups produced is significantly smaller in FST288-only females at all ages. D, The number of embryos collected at 0.5 dpc after superovulation was reduced by nearly half (P < 0.01) in FST288-only females (black bars) compared with WT females (white bars). E, The number of embryos collected at 3.5 dpc after superovulation was similarly reduced by nearly half in FST288-only females compared with WT females, a ratio that held up even when embryos were subcategorized into blastocyst, morula, or degenerating. F, When the results from E were expressed as a percentage of the total number of embryos, the differences in each category disappeared. This indicates that FST288-only females ovulate fewer eggs per cycle, but their developmental potential is not different from WT embryos.

To examine whether this fertility reduction was due to reduced number of ovulated oocytes or to a deficiency in their postovulation survival, we used superovulation to induce maximal ovulations and examined recovered embryos at 0.5 and 3.5 d postcoitum (dpc). The overall number of ovulated oocytes was determined by collection of embryos/eggs in the fallopian tubes at 0.5 dpc. The total number of embryos/eggs was reduced compared with WT females (Fig. 4D). The total number of embryos recovered at 3.5 dpc was also significantly reduced in FST288-only females, as was the number of blastula, morula, or degeneration staged embryos (Fig. 4E). However, if expressed as a percentage of recovered embryos, the embryo number at each stage was not different (Fig. 4F), indicating that altered FST expression does not appear to reduce oocyte quality or early embryo development but rather alters the number of follicles that develop and ovulate each cycle.

Follicle maturation in FST288-only mice

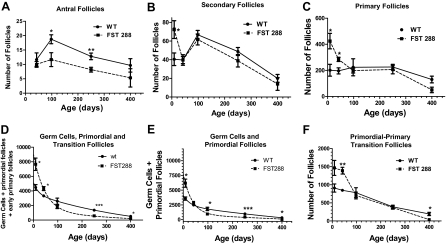

To further analyze follicle development in FST288-only mice, ovaries from 8.5- to 400-d-old females were completely sectioned and all nonatretic and atretic follicles categorized and counted. There was no difference between the genotypes in antral follicle number at 42 d of age, but at 100 and 250 d, significantly fewer antral (preovulatory plus tertiary) follicles were present in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT ovaries (Fig. 5A). Although this difference remained at 400 d, it was no longer statistically significant. Nevertheless, these observations suggest that fewer follicles were entering the antral follicle pool to be available for ovulation and fertilization, thereby contributing to the reduced fertility of the FST288-only females.

Figure 5.

Analysis of follicle and germ cell numbers in FST288-only and WT females. Ovaries from FST288-only (▪) and WT (•) females were collected (n = 3–6) at ages shown and analyzed for follicle stage and number as described in methods. A, The total numbers of nonatretic tertiary and antral follicles per ovary is significantly smaller in FST288-only females at 100 and 250 d, whereas this number is not different at puberty (d 42). B, The numbers of secondary follicles per ovary are significantly greater in FST288-only females at 8.5 d of age compared with WT females, but at puberty and later, this difference is no longer detectable. C, The numbers of primary follicles per ovary are significantly greater in FST288-only females at 8.5 and 42 d of age compared with WT females, a difference that becomes undetectable by 100 d of age. D, The total numbers of germ cells (still in oocyte nests), primordial follicles, and early primary follicles per ovary are almost double at 8.5 d of age in FST288-only females compared with WT females. However, this difference is not detectable after puberty through accelerated loss from this pool of oocytes. In addition, at 250 and 400 d of age, there are significantly fewer primordial follicles in FST288-only females compared with WT females. E, Total numbers of germ cells and primordial follicles are shown. This plot does not include those primordial follicles showing signs of activation that were included in D. Again, follicle number is nearly double at 8.5 d of age in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT, but the number decreases more rapidly in FST288-only ovaries so that primordial follicle number is significantly smaller than WT by 250 d of age. F, The numbers of activated primordial-primary transition follicles are significantly greater at 8.5 and 42 d of age in FST288-only females compared with WT females. By 400 d of age, the number of activated follicles is significantly greater in WT compared with FST288-ovaries. This accelerated activation may account for the faster depletion of the primordial follicle pool in these mice as well as the earlier ovarian failure. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To determine whether this difference was limited to antral follicles, we examined secondary follicle number in WT and FST288-only ovaries from 8.5–400 d. Secondary follicle number was significantly greater in FST288-only ovaries at 8.5 d but not different from WT at all other ages (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the number of primary follicles was significantly larger in FST288-only ovaries, being more than double WT at 8.5 d of age (P < 0.05) and 1.5-fold larger at 42 d of age (P < 0.05) but became equal to WT by 100 d and older (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that a larger pool of growing primary follicles led to an initial increase in secondary follicles in FST288-only ovaries that disappeared once the females reached sexual maturity. To determine whether this follicle loss was due to atresia, clearly atretic follicles were counted. More atretic secondary follicles were observed in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT littermates at 42 and 250 d, but the number of atretic antral follicles were not significantly different (supplemental Fig. 2). These results suggest that the reduced numbers of antral follicles in FST288 females may be due, at least in part, to increased atresia of secondary follicles.

For estimation of the number of primordial follicles, primordial and early primary (primary to primordial transition) follicles are often combined into one category as primordial follicles (12,16). Moreover, at 8.5 d of age, about 10% of oocytes are still in germ cell nests in FST88-only mice compared with 3% for WT females (data not shown). Therefore, the total number of germ cells, primordial follicles, and early primary follicles was quantitated to evaluate the total reserve pool of oocytes. At 8.5 and 42 d, the total number of oocytes in this reserve pool was nearly twice as large for FST288-only ovaries compared with that of WT ovaries (Fig. 5D; P < 0.05). This difference was no longer detectable at 100 d of age, and beyond 100 d of age, the number of reserve oocytes was smaller in FST288-only ovaries, a difference that became significant by 250 d (P < 0.001) and continued at least until 400 d (Fig. 5D). Even when early primary follicles are deleted from the analysis, total germ cell and primordial follicle number is still double in FST288-only ovaries compared with WT at 8.5 d of age (Fig. 5E). These data demonstrate that FST288-only females begin life with a larger primordial follicle pool, but by 100 d of age, this pool is smaller than WT ovaries, suggesting that the rate of primordial follicle depletion is greater in FST288-only mice.

The more rapid depletion of primordial follicles in FST288-only ovaries may be due to accelerated activation because the number of primordial follicles showing evidence of entering the growing follicle pool (primordial to primary transition), as detected by appearance of cuboidal granulosa cells surrounding the oocyte (17,18,19), in FST288-only ovaries was nearly double that of WT ovaries (Fig. 5F; P < 0.01 for 42 d). Interestingly, by 400 d, there were significantly fewer primary-primordial transition follicles in FST288-only ovaries (Fig. 5F; P < 0.05) compared with WT ovaries. These results suggest that FST288-only females begin life with more primordial follicles that become activated and enter the growing follicle pool in larger numbers than those in WT mice so that by 100 d of age, the primordial follicle pool and the number of growing follicles is reduced in FST288-only females.

This accelerated depletion of primordial follicles suggests that FST288-only females might experience ovarian failure before WT females. The mean age for ovarian failure was not statistically different in the breeding pairs used for this study (data not shown). However, three of seven FST288-only females ceased reproducing before 210 d of age, whereas all of the WT females continued to have litters until at least 270 d of age. Taken together with the analysis of ovarian follicle number, it appears that the FST288-only mouse might be a model for human premature ovarian failure in which reproduction becomes more sporadic and then ceases earlier due to primordial stock depletion (13).

Discussion

Three protein isoforms are derived from the single Fst gene (3,4). Although the neonatal lethality of the global Fst KO mouse (8) demonstrated the importance of FST for normal development and adult homeostasis, the roles of the individual FST isoforms remains to be defined. In vitro, the FST288 isoform, and to a lesser degree the FST303 isoform, bind to cell surface proteoglycans, a property not shared by the FST315 isoform (3). This gives the FST288 isoform greater effectiveness in antagonizing autocrine-acting activin at the cell surface (6), whereas the FST315 isoform that is largely found in the circulation (7) and the gonadal FST303 isoform are less effective (6). These results suggest that the FST288 isoform might be sufficient to permit embryonic and neonatal development so that the role of FST in adults could be investigated in vivo.

In the present study, we modified the mouse genome to delete the natural alternative splicing site and insert a new stop codon with the intention of allowing only the FST303 mRNA to be produced. A cryptic acceptor site in the Neo cassette created an extended mRNA that was found to insert a stop codon at the end of exon 5, allowing only the FST288 protein to be translated. To verify this, we obtained follicular fluid from PMSG-treated WT and FST288-only females and found that although follicular fluid from WT mice have the expected FST315, -303, and -288 isoforms, only the FST288 isoform was detected in FST288-only mice, thereby verifying that our genetic mutation had the desired effect. Both Northern blot and qPCR studies demonstrated that total Fst mRNA was reduced compared with WT, a finding consistent with reduced FST protein identified by immunohistochemistry. Interestingly, the protein levels of FST288 isoform was not altered in FST288-only mice compared with WT mice, suggesting that the phenotypes observed in FST288-only mice have resulted from deletion of FST303 and FST315 isoforms. Using a new mouse FST antibody, we localized FST protein in neonatal and adult mouse ovary sections to both granulosa cells and oocytes in WT mice, and this FST was detected in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Interestingly, in adult FST288-only ovaries, FST staining was primarily found in the cytoplasm, but in neonatal ovaries, many germ cells retained nuclear staining (data not shown). The functional effects of this altered intracellular compartmentalization remain to be fully elucidated, but because the FST288 isoform alone is produced in FST288-only mice, they suggest that the FST303 or -315 isoforms may be transported to the nucleus of both granulosa cells and oocytes in adult WT mice, a process that includes FST288 in neonates. Regardless of the subcellular alterations, the FST288-only mouse confirms that this isoform is sufficient for survival to adulthood, thereby allowing analysis of the role of FST isoforms in adult physiology.

Although total Fst mRNA was reduced in ovaries, we detected no difference in FST288-only testes and a significant increase in Fst mRNA in metabolic tissues like liver. At the same time, ovarian activin A and B, Smads 2 and 3, and Fstl3 mRNA levels were not different between the genotypes. These observations indicate that Fst expression is differentially regulated between the sexes and in different tissues so that loss of the FST315 and FST303 isoforms can have different effects in reproductive vs. nonreproductive tissues. Activin has been shown to directly regulate Fst expression (20,21), and this regulation occurs via a novel Smad binding region within intron 1 that involves Smad 3 (22) and the FoxL2 transcription factor (23). Thus, it is possible that the differential expression of Fst in various tissues in the FST288-only mouse is mediated by tissue-specific expression levels of FoxL2, because Smad3 does not seem to be altered in these mice. Our results also support the notion that FST may have important roles in regulating activin or other TGFβ family ligands in nonreproductive tissues, an observation supported by the enhanced glucose tolerance and enlarged islets observed in FSTL3 KO mice (14).

Adult FST288-only females are subfertile with reduced litter size and frequency. The longer inter-litter intervals suggest alterations in regulation of pituitary FSH biosynthesis in FST288-only females, a process that depends on regulation of activin action by primarily FST315 (21,24). This possibility remains to be further investigated. The reduced litter size is consistent with an ovarian defect, which was confirmed in superovulated FST288-only females who had fewer ovulated eggs and fertilized embryos compared with WT females, suggesting altered follicle development or selection into the antral pool might be responsible. These superovulation experiments were conducted at an age (42–45 d) when the number of developing antral follicles was not different between FST288-only and WT females, suggesting defects in development from antral follicles to ovulatory follicles in FST288-only mice. It was recently demonstrated that FST was critical for normal embryo development in vitro in both cows and primates and that FST reduction decreased embryo quality after fertilization (25,26). Taken together, these results suggest that at least one contributing factor to the subfertility in FST288-only females is a reduced quality of the follicle and/or oocyte, leading to fewer fertilized embryos and pups. The question of whether exogenous FST can rescue fertilized embryos of FST288-only females will be addressed in the future with in vitro fertilization and culture experiments.

Detailed follicle counting in ovaries from nonstimulated FST288-only females identified a significant reduction in the number of nonatretic antral follicles at ages greater than 100 d, whereas the number of secondary follicles was similar in the two genotypes, suggesting impaired survival of follicles after selection into the antral pool, which could also contribute to the reduced litter size in unstimulated FST288-only mice relative to WT females. This observation supports the concept that deletion of the FST315 and FST303 isoforms and/or reduction in total FST production alters follicle/oocyte quality and maintenance/growth of antral follicles. When Fst was deleted specifically from granulosa cells using a conditional KO approach, follicle development was inhibited, leading to smaller and less frequent litters, fewer ovarian follicles, and ovulation and fertilization defects of the oocytes contained in those follicles, leading to premature cessation of ovarian activity (9). In addition, total and antral follicle numbers were vastly reduced by 6 months of age and absent at 8 months, with vastly reduced fertilization potential of oocytes after 6 months of age in FST conditional KO mice (9). This phenotype is quite similar to but more severe than that observed in FST288-only mice, suggesting that the FST288 isoform can compensate, at least in part, for loss of FST and restore at least some follicle development and fertility beyond 8 months of age.

Using a different approach to investigate isoform-specific actions, Lin et al. (10) created transgenic mice in which the human FST288 or -315 cDNA linked to the human FST promoter were crossed with FST KO mice to attempt to rescue the neonatal lethality of the FST KO mouse. Mice expressing human FST288 in the Fst-null background were similar to FST KO mice in their small size, taut skin, and absent whisker phenotype but were not cyanotic and lived for 12–24 h. Mice transgenically expressing the human FST315 transgene survived to adulthood but showed some musculoskeletal defects, early growth retardation, impaired tail growth, and female infertility due to a drastic reduction in follicle numbers and complete absence of antral follicles. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between our results and the Lin et al. study is their use of the human promoter to direct transgenic FST expression, which may not reliably recapitulate normal mouse FST expression levels and tissue distribution. Nevertheless, from these studies, we conclude that at least some FST288 is necessary for normal follicle development and that the FST315 isoform, and perhaps its FST303 derivative, are unable to accomplish this function. Taken together, it appears that FST plays isoform-specific roles in granulosa cell, oocyte, and follicle development that may involve functions dependent on differential subcellular compartmentalization that relates to the unique biochemical properties of the FST isoforms (6,27).

Although the number of antral follicles was reduced in FST288-only mice, the number of primary and secondary follicles from which these follicles are recruited was not different from WT females after puberty. However, the number of primary follicles was significantly increased at 8.5 and 42 d, and secondary follicles were increased at 8.5 d compared with WT females, suggesting that the total number of follicles was not reduced before sexual maturation. This excess in primary and secondary follicles appears to dissipate through atresia because the number of activating primordial follicles, that is, those primordial follicles showing signs of leaving the quiescent pool and entering the growing pool, is significantly increased at these ages. Because these follicles do not appear in the antral follicle pool, they likely become atretic and are deleted from the follicle pool so that the total number of primary and secondary follicles are no longer different after 42 days of age. This deduction is supported by the significantly increased number of atretic secondary follicles counted in FST288-only ovaries. These observations also suggest that enhanced activin activity resulting from altered and/or reduced FST expression may be an important signal for activation of primordial follicles that if continued throughout the reproductive lifespan could lead to premature exhaustion of the primordial follicle pool and ovarian failure.

The source of these extra developing follicles is an increased number of primordial follicles evident at 8.5 d, where this pool is twice as large in FST288-only females as that found in WT females. By 42 d, the number of primordial follicles is equivalent to WT, and at later ages, the primordial follicle pool is smaller in FST288-only females. Taken together with the other follicle counts, these observations suggest that deletion of FST315 or FST303 and/or reduction of overall FST expression, leads to an increased primordial follicle endowment that is reduced through early activation so that by the time of puberty, this excess is gone. However, the accelerated depletion leads to a reduced primordial follicle pool in older FST288-only females. These observations are in agreement with the recent demonstration that activin administration to female neonates between 0 and 4 d results in a larger primordial follicle endowment that dissipates by puberty (12), suggesting that the overall effect of the genetic modifications leading to the FST288-only mouse is a general increase in activin activity. Thus, our results are consistent with the concept that activin, as regulated by FST, is a critical regulator of both follicle formation and activation into the growing follicle pool as well as having important actions contributing to overall follicle/oocyte quality. In addition, because one prevailing hypothesis for the onset of menopause is a reduction in primordial follicle endowment below a critical threshold (28), an event that occurs early in premature ovarian failure (13), and that the FST288-only females gradually lose fertility through increased inter-litter intervals and reduced litter size as they age, our results suggest that altered activin or FST activity can lead to accelerated loss of primordial follicles and premature reduction and/or cessation of ovarian activity. Taken together with other models of altered FST production, our results therefore support a more focused examination of a possible role for these factors in human premature ovarian failure.

Although the importance of FST has been recognized since the neonatal lethality of the global KO mouse was described (8), the actual physiological roles of FST in the adult have been substantially more difficult to elucidate. Moreover, like many genes, multiple FST isoforms are produced that have distinct biochemical properties (6), raising the question of what specific biological roles they play in vivo. The FST288-only mouse contributes to both of these important questions by demonstrating that the FST288 isoform itself is sufficient for embryonic development and survival to adulthood. Moreover, the fertility defects involving altered ovarian follicle formation and development demonstrate that FST has a critical role in adults in regulating reproduction, but the FST288 isoform itself cannot completely compensate for loss of the FST303 and -315 isoforms. Continued analysis of these mice will likely reveal additional roles for FST and its isoforms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical assistance of histologist Brooke Bentley and technician Amy Mahan whose contributions were critical for the success of these studies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK075058 and R21HD062859 (to A.L.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 23, 2009

Abbreviations: dpc, Days postcoitum; FST, follistatin; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; KO, knockout; PMSG, pregnant mare serum gonadotropin; qPCR, quantitative PCR; WT, wild type.

References

- Welt C, Sidis Y, Keutmann H, Schneyer A 2002 Activins, inhibins, and follistatins: from endocrinology to signaling. A paradigm for the new millennium. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 227:724–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Schneyer AL 2009 The biology of activin: recent advances in structure, regulation and function. J Endocrinol 202:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino K, Kurosawa N, Nakamura T, Takio K, Shimasaki S, Ling N, Titani K, Sugino H 1993 Molecular heterogeneity of follistatin, an activin-binding protein. J Biol Chem 68:15579–15587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki S, Koga M, Esch F, Cooksey K, Mercado M, Koba A, Ueno N, Ying SY, Ling N, Guillemin R 1988 Primary structure of the human follistatin precursor and its genomic organization. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 85:4218–4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S, Ling N, Shimasaki S 1992 Localization of the heparin binding site of follistatin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 90:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidis Y, Mukherjee A, Keutmann H, Delbaere A, Sadatsuki M, Schneyer A 2006 Biological activity of follistatin isoforms and follistatin like-3 are dependent on differential cell surface binding and specificity for activin, myostatin and bone morphogenetic proteins. Endocrinology 147:3586–3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneyer AL, Wang Q, Sidis Y, Sluss PM 2004 Differential distribution of follistatin isoforms: application of a new FS315-specific immunoassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5067–5075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Lu N, Vogel H, Sellheyer K, Roop DR, Bradley A 1995 Multiple defects and perinatal death in mice deficient in follistatin. Nature 374:360–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM 2004 Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol Endocrinol 18:953–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SY, Craythorn RG, O'Connor AE, Matzuk MM, Girling JE, Morrison JR, de Kretser DM 2008 Female infertility and disrupted angiogenesis are actions of specific follistatin isoforms. Mol Endocrinol 22:415–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Tran M, Agno J, Li X, Brown CW, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM 2007 Intraovarian activins are required for female fertility. Mol Endocrinol 21:2458–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol-Gould SK, Kreeger PK, Selkirk CG, Kilen SM, Cook RW, Kipp JL, Shea LD, Mayo KE, Woodruff TK 2006 Postnatal regulation of germ cells by activin: the establishment of the initial follicle pool. Dev Biol 298:132–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosden RG, Faddy MJ 1998 Biological bases of premature ovarian failure. Reprod Fertil Dev 10:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Sidis Y, Mahan A, Raher MJ, Xia Y, Rosen ED, Bloch KD, Thomas MK, Schneyer AL 2007 FSTL3 deletion reveals roles for TGF-β family ligands in glucose and fat homeostasis in adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:1348–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino K, Nakamura T, Takio K, Miyamoto K, Hasegawa Y, Igarashi M, Titani K, Sugino H 1992 Purification and characterization of high molecular weight forms of inhibin from bovine follicular fluid. Endocrinology 130:789–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol-Gould SK, Kreeger PK, Selkirk CG, Kilen SM, Mayo KE, Shea LD, Woodruff TK 2006 Fate of the initial follicle pool: empirical and mathematical evidence supporting its sufficiency for adult fertility. Dev Biol 298:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MK 2005 Regulation of primordial follicle assembly and development. Hum Reprod Update 11:461–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson E, Skinner MK 2001 Cellular interactions that control primordial follicle development and folliculogenesis. J Soc Gynecol Investig 8:S17–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Skinner MK 1999 Kit-ligand/stem cell factor induces primordial follicle development and initiates folliculogenesis. Endocrinology 140:4262–4271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilezikjian LM, Vaughan JM, Vale WW 1993 Characterization and the regulation of inhibin/activin subunit proteins of cultured rat anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology 133:2545–2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besecke LM, Guendner MJ, Sluss PA, Polak AG, Woodruff TK, Jameson JL, Bauer-Dantoin AC, Weiss J 1997 Pituitary follistatin regulates activin-mediated production of follicle-stimulating hormone during the rat estrous cycle. Endocrinology 138:2841–2848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount AL, Vaughan JM, Vale WW, Bilezikjian LM 2008 A Smad-binding element in intron 1 participates in activin-dependent regulation of the follistatin gene. J Biol Chem 283:7016–7026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount AL, Schmidt K, Justice NJ, Vale WW, Fischer WH, Bilezikjian LM 2009 FoxL2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate follistatin gene transcription. J Biol Chem 284:7631–7645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besecke LM, Guendner MJ, Schneyer AL, Bauer-Dantoin AC, Jameson JL, Weiss J 1996 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone regulates follicle-stimulating hormone-β gene expression through an activin/follistatin autocrine or paracrine loop. Endocrinology 137:3667–3673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Bettegowda A, Wee G, Ireland JJ, Smith GW 2009 Molecular determinants of oocyte competence: potential functional role for maternal (oocyte-derived) follistatin in promoting bovine early embryogenesis. Endocrinology 150:2463–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandeVoort CA, Mtango NR, Lee YS, Smith GW, Latham KE 2009 Differential effects of follistatin on nonhuman primate oocyte maturation and pre-implantation embryo development in vitro. Biol Reprod 81:1139–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Sidis Y, Mukherjee A, Xia Y, Schneyer A 2005 Differential biosynthesis and intracellular transport of follistatin isoforms and follistatin-like-3. Endocrinology 146:5052–5062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ, Gosden RG 1996 A model conforming the decline in follicle numbers to the age of menopause in women. Hum Reprod 11:1484–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.