Abstract

Inhibin is an atypical member of the TGFβ family of signaling ligands and is classically understood to function via competitive antagonism of activin ligand binding. Inhibin-null (Inha−/−) mice develop both gonadal and adrenocortical tumors, the latter of which depend upon gonadectomy for initiation. We have previously shown that gonadectomy initiates adrenal tumorigenesis in Inha−/− mice by elevating production of LH, which drives aberrant proliferation and differentiation of subcapsular adrenocortical progenitor cells. In this study, we demonstrate that LH signaling specifically up-regulates expression of TGFβ2 in the subcapsular region of the adrenal cortex, which coincides with regions of aberrant Smad3 activation in Inha−/− adrenal glands. Consistent with a functional interaction between inhibin and TGFβ2, we further demonstrate that recombinant inhibin-A antagonizes signaling by TGFβ2 in cultured adrenocortical cells. The mechanism of this antagonism depends upon the mutual affinity of inhibin-A and TGFβ2 for the signaling coreceptor betaglycan. Although inhibin-A cannot physically displace TGFβ2 from its binding sites on betaglycan, binding of inhibin-A to the cell surface causes endocytic internalization of betaglycan, thereby reducing the number of available binding sites for TGFβ2 on the cell surface. The mechanism by which inhibin-A induces betaglycan internalization is clathrin independent, making it distinct from the mechanism by which TGFβ ligands themselves induce betaglycan internalization. These data indicate that inhibin can specifically antagonize TGFβ2 signaling in cellular contexts where surface expression of betaglycan is limiting and provide a novel mechanism for activin-independent phenotypes in Inha−/− mice.

Inhibin functionally antagonizes TGFbeta2 signaling by downregulating surface expression of its obligate co-receptor betaglycan. The unique mechanism and consequences of receptor downregulation are discussed.

The TGFβ family of signaling ligands plays a wide variety of roles in the development and maintenance of the mammalian endocrine system (1,2). Whereas several different ligands from this family serve distinct and highly specific functions, activins and inhibins are of particular interest because of their opposing regulatory roles in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and gonads (2,3). Activins exert their function by signaling through heterotetrameric complexes composed of activin-type II receptors (ActRII or ActRIIB) and activin-type I receptors, which specifically activate Smad2 and Smad3 effector proteins by phosphorylation (4). Once activated, Smad2 and Smad3 disengage from cytoplasmic anchoring proteins, oligomerize, and move into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes (5).

In contrast to activins, inhibins do not signal directly but, instead, function by antagonizing activin signaling. Inhibins perform this role by virtue of their heterodimeric structure, which is composed of a unique α-subunit (Inhα) coupled to a β-subunit (InhβA or InhβB) shared with homodimeric activin (Inhβ/Inhβ) (6). Whereas the symmetrical structure of activin allows it to form complete heterotetrameric receptor complexes, the asymmetrical structure of inhibin allows it to bind only to the ActRII/IIB components, thereby competitively blocking potential activin-binding sites (7).

The effectiveness of inhibin as an antagonist is significantly enhanced by its binding to betaglycan, a cell surface proteoglycan that interacts with the Inhα-subunit. Betaglycan acts as a coreceptor for inhibin and several other TGFβ family members, most notably TGFβ2 (8,9). Overlapping requirements for betaglycan coreceptor binding sites between inhibin and other TGFβ family members suggest that inhibin could potentially antagonize a broader array of TGFβ ligands than is currently appreciated, although this hypothesis has not been adequately explored (10).

Inhibin α-subunit knockout mice (Inha−/−) display defects in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis regulation and develop gonadal sex cord-stromal tumors of a mixed steroidogenic cell identity (11,12). The cellular proliferation defect in gonadal tissues from Inha−/− mice appears to result from unopposed activin signaling, which produces a potent mitogenic stimulus for steroidogenic cells of the gonad (13,14). Some of the more subtle phenotypes in Inha−/− mice, however, are not easily explained by interactions between inhibin and activin alone. One of these phenotypes is the formation of mixed sex cord-stromal tumors within adrenal glands of Inha−/− mice upon gonadectomy (11,12). Although these tumors are phenotypically similar to those found in the gonad, the process by which they arise is distinct (15). Because the adrenal gland does not express significant levels of endogenous activins, it is possible that adrenal inhibin can instead antagonize another TGFβ family member that is responsible for the unique initiation of adrenal tumors in Inha−/− mice.

In this study we sought to identify which TGFβ family member is responsible for adrenal tumorigenesis in Inha−/− mice. Our data suggest that TGFβ2, and not activins, may be responsible for this phenomenon and that inhibin is able to antagonize TGFβ2 signaling by a novel mechanism involving the down-regulation of betaglycan expression on the cell surface. These data are consistent with a functional interaction between these two ligands in the adrenal cortex and suggest that an important role for adrenal inhibin is to antagonize endogenous TGFβ2 signaling.

Results

TGFβ2 is specifically up-regulated in the adrenal by LH signaling

Previous studies in our laboratory and in others have demonstrated the importance of LH in the initiation of adrenocortical tumorigenesis (16,17,18). Mice that chronically overexpress this hormone (bLH-βCTP transgenic mice) activate gonadal gene expression in the adrenal gland and dramatically accelerate adrenocortical tumor development when crossed with Inha−/− mice (15,16,19). We previously found that bLH-βCTP mice display ectopic activation of Smad3 in the subcapsular progenitor zone of the adrenal cortex, suggesting that LH specifically activates transcription of a TGFβ family member capable of signaling through Smad3 (20). Based on these observations, we asked whether increased LH signaling to the adrenal gland changes the relative expression of any TGFβ or activin ligand.

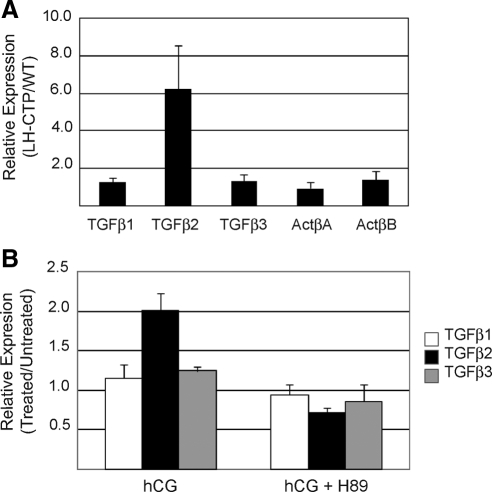

To answer this question we measured the relative expression of the three TGFβ genes and two activin β-subunit genes in the adrenals of bLH-βCTP mice and wild-type littermates by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). These data indicate that of the five genes, only TGFβ2 is specifically up-regulated in bLH-βCTP mice. TGFβ2 is expressed 6-fold higher in bLH-βCTP adrenals than in wild-type adrenals, whereas none of the other ligands are expressed more than 1.6-fold in the same tissue. These data suggest that TGFβ2 may be specifically up-regulated in the adrenal gland by LH signaling, supporting the hypothesis that TGFβ2 is responsible for activating Smad3 in the adrenal glands of bLH-βCTP mice.

Figure 1.

TGFβ2 is specifically up-regulated by LHR signaling. A, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TGFβ and activin subunit gene expression was performed on RNA transcripts harvested from the adrenal glands of wild-type and bLH-βCTP mice. Values for each transcript were normalized to Arbp expression and are displayed as the ratio of average values from bLH-βCTP mice to wild-type mice. Error bars represent the standard deviation of seven mice per group. B, Primary Inha−/− adrenocortical tumor cells were explanted to culture and treated 24 h with media only, hCG (50 ng/ml), or hCG and the PKA inhibitor H89 (2 μm). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA harvested from each sample. Values for each gene were normalized to 18s rRNA expression and are displayed as the ratio of values from treated and untreated cells. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three separate experimental replicates. WT, Wild type.

To further test the link between LH signaling and TGFβ2 expression, primary adrenal tumor cells from Inha−/− mice were explanted to cell culture for 24 h in the presence or absence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which activates the LH receptor (LHR) similarly to LH. We observed that cells treated with hCG specifically up-regulated TGFβ2 expression, consistent with our findings in bLH-βCTP mice (Fig. 1B). We also found that cotreatment of tumor cells with hCG and the protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor H89 (2 μm) attenuated the ability of hCG to increase TGFβ2 expression, indicating that LHR activates TGFβ2 expression via the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. These data are consistent with previous reports that indicate the cAMP/PKA pathway is a central mediator of LHR signaling, and that the TGFβ2 promoter responds to this pathway via identifiable cAMP response elements (21).

Adrenocortical cells express TGFβ receptors and are responsive to TGFβ2 ligand

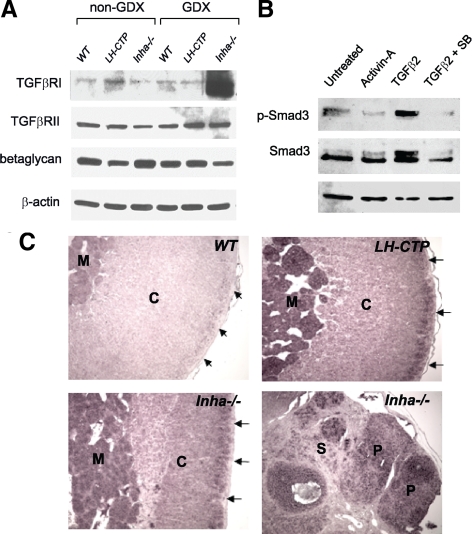

In addition to showing that TGFβ2 is specifically induced by hCG/LH signaling through LHR, we also sought to determine whether TGFβ2 could act as an autocrine signaling factor in the normal adrenal cortex. To signal efficiently, TGFβ2 requires the presence of TβRI (Alk5), TβRII, and TβRIII (betaglycan). To determine whether all three of the TGFβ receptors are present in the adrenal, we performed immunoblots for each protein on whole adrenal extracts from wild-type, bLH-βCTP, and Inha−/− mice both before and after gonadectomy. We found that TβRII and TβRIII are strongly expressed in the wild-type adrenal cortex, but that TβRI is only weakly present (Fig. 2A). Expression of TβRI protein is elevated after surgical gonadectomy, however, indicating that it may be induced by elevated gonadotropins in a similar fashion to TGFβ2 (Fig. 2A). These findings imply that increased LH signaling induced by gonadectomy indirectly causes the activation of Smad3 by up-regulating expression of the TGFβ2 ligand, while at the same time increasing cellular sensitivity to the ligands via up-regulating expression of TβRI.

Figure 2.

TGFβ2 is expressed in the adrenal cortex and activates Smad3 signaling in primary mouse adrenocortical cells. A, Immunoblot analysis of TGFβ receptor expression was performed on 10–40 μg of whole adrenal gland protein lysates from 2 month-old female mice of the indicated genotype. Equal protein amounts were loaded for each sample. Blots were probed with antibodies to TGFβRI (Alk5), TGFβRII, and TGFβRIII (betaglycan), as well as β-actin to demonstrate equal protein loading. B, Adrenals from six age-matched wild-type female mice were pooled and explanted to primary culture in six-well plates. After 16 h of culture, the cells were washed and treated with vehicle alone (PBS, lane1), activin-A (2 ng/ml, lane 2), TGFβ2 (1 ng/ml, lane 3), or TGFβ2 plus the Alk5 inhibitor SB431542 (1 μm, lane 4) for 16 h. Protein lysates were loaded in equal amounts for each sample and submitted to immunoblot analysis for expression and activation (phosphorylation) of Smad3. Blots were also probed for β-actin to indicate equal protein loading. C, Nonradioactive in situ hybridization analysis of TGFβ2 expression was performed on sections of paraffin-embedded adrenal glands harvested from wild-type (WT), bLH-βCTP, and Inha−/− mice 20–30 wk after gonadectomy. Regions of the tissue that express TGFβ2 transcripts hybridize to the digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe and are detected by alkaline phosphatase activity (purple) produced by an anti-DIG/AP-conjugated antibody. The bottom two panels are derived from adjacent normal adrenal and adrenocortical tumor tissue from the same Inha−/− adrenal sample. Staining in the adrenal cortex (C) is enhanced in the subcapsular region (arrows) and is also prominently seen in tumor parenchyma (P), but not in the cortical stroma (S). The adrenal medulla (M) also stains purple due to endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity. AP, Alkaline phosphatase; GDX, gonadectomy; DIG, digoxigenin.

To further test the responsiveness of the adrenal cortex to TGFβ2, we explanted primary adrenocortical cells from wild-type mice and treated them in the presence or absence of TGFβ2. Primary adrenocortical cells demonstrate robust phosphorylation of Smad3 when treated with TGFβ2, whereas treatment with activin failed to elicit this response (Fig. 2B). Cotreatment of cells with the TβRI/Alk5 kinase inhibitor SB431542 (1 μm) blocked the ability of TGFβ2 to stimulate Smad3 phosphorylation, supporting the conclusion that TGFβ2 activates Smad3 in the adrenal cortex via its canonical receptor complex.

TGFβ2 expression coincides with Smad3 activation in the adrenal cortex

Previous studies in our laboratory have indicated that Smad3 is only weakly activated by phosphorylation in the adrenal gland under normal homeostatic conditions, suggesting the absence of stimulatory signaling through the TGFβ and/or activin pathways in this tissue. When gonadotropin levels are elevated to supraphysiological levels, however, Smad3 is specifically activated in the subcapsular proliferating zone of the adrenal cortex, which contains adrenocortical progenitor cells (15,20). Although it is clear that the up-regulation of TGFβ2 expression and activation of Smad3 temporally coincide in the context of elevated LH signaling, it remains uncertain whether these two LH-driven events occur in the same population of cells within the adrenal cortex.

To determine whether the expression of TGFβ2 spatially coincides with Smad3 activation, we performed in situ hybridization for TGFβ2 transcripts in the adrenals of wild-type, bLH-βCTP, and Inha−/− mice that had been surgically gonadectomized. All three of these strains demonstrated strong subcapsular staining for TGFβ2 in the adrenal cortex, indicating that TGFβ2 expression occurs in the same region of the adrenal gland as Smad3 activation (Fig. 2C). In addition, we also performed the in situ hybridization on tissue from Inha−/− adrenocortical tumors. Within these tumors, TGFβ2 expression was specifically restricted to the tumor parenchyma and was not found in the surrounding stromal cells (Fig. 2C). These data are consistent with previous findings in our laboratory that indicated Inha−/− adrenal tumors are caused by the uncontrolled expansion of aberrantly programmed subcapsular cells, which demonstrate sustained activation of Smad3 in the absence of inhibin. The restricted localization of TGFβ2 expression to the same adrenocortical region as these Smad3-positive cells supports our hypothesis that in the adrenal gland, tumor initiation proceeds through activation of TGFβ2.

Inhibin functionally antagonizes TGFβ2 signaling in vitro

Having established that increased LH signaling induces the specific expression of TGFβ2 in the adrenal cortex and that the adrenal cortex is sensitive to this ligand, we turned to the Y1 mouse adrenocortical cell line to address the question of whether inhibin can functionally antagonize TGFβ2 signaling (22). Y1 cells recapitulate many of the growth and signaling paradigms found in primary corticosteroid-secreting adrenocortical cells, and had been shown previously to respond to TGFβ1 signaling (23).

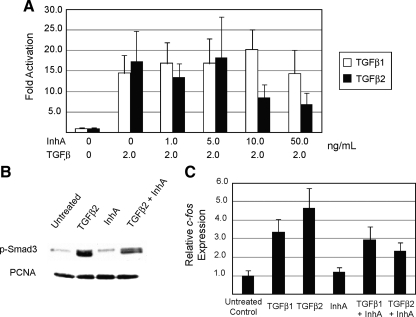

Using the Smad3-dependent 3TP-lux reporter plasmid as a readout for TGFβ signaling, we found that Y1 cells respond equally well to TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 with an EC50 of 0.5 ng/ml, but fail to respond at all to recombinant human activin (data not shown). To determine whether inhibin could attenuate this effect, we pretreated Y1 cells for 8 h with increasing concentrations of recombinant inhibin-A and then stimulated the cells with fixed concentrations of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 for 16 h to determine whether inhibin can antagonize TGFβ-mediated stimulation of the 3TP-lux reporter. Whereas activation of 3TP-lux by TGFβ1 was unchanged by inhibin-A, activation of the reporter by TGFβ2 was decreased by inhibin-A at concentrations greater than 10 ng/ml (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Inhibin functionally antagonizes TGFβ2 signaling in vitro. A, Luminescent assays for 3TP-lux reporter activation were performed in Y1 adrenocortical cells treated with a fixed amount of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 (2 ng/ml) and increasing doses of recombinant inhibin-A peptide as indicated. 3TP-lux activity was normalized to the luminescent signal from a constitutively expressed pCMV-Renilla reporter vector that was cotransfected with 3TP-lux into Y1 cells. B, Y1 cells were treated with vehicle (PBS), TGFβ2 (0.5 ng/ml), inhibin-A (100 ng/ml), or TGFβ2 plus inhibin-A for 16 h. Immunoblot analysis was performed on 10–20 μg of protein lysates loaded in equal amounts for each sample. Blots were probed with antibodies to phospho-Smad3 to indicate TGFβ2 signaling activity and proliferating cell nuclear antigen to indicate equal protein loading. C, Y1 cells were treated with vehicle (PBS), TGFβ1 (0.5 ng/ml), TGFβ2 (0.5 ng/ml), inhibin-A (100 ng/ml), or TGFβ ligand plus inhibin-A for 16 h. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of c-fos gene expression was performed on total RNA extracted from each sample. Values for c-fos were normalized to Arbp expression, with error bars indicating the standard error of three separate measurements. PCNA, Proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

To further test the ability of inhibin to antagonize TGFβ2 signaling, we measured the activation of endogenous Smad3 in Y1 cells that were treated with TGFβ2 alone or with recombinant inhibin-A. Treatment of Y1 cells with TGFβ2 leads to strong Smad3 phosphorylation, whereas treatment with inhibin-A alone has no effect (Fig. 3B). In contrast, treatment of cells with TGFβ2 and inhibin-A partially attenuates Smad3 phosphorylation. Similar data were generated using quantitative RT-PCR detection of the immediate-early gene c-fos, which has been shown to respond robustly to TGFβ signaling via Smad3 (24). Endogenous expression of c-fos in Y1 cells was induced 3-fold by TGFβ1 and 4- to 5-fold by TGFβ2, whereas inhibin-A alone had no effect (Fig. 3C). Coordinate treatment of Y1 cells with TGFβ1 and inhibin-A showed no difference from TGFβ1 alone, whereas cotreatment with inhibin and TGFβ2 decreased c-fos expression by 50% compared with TGFβ2 only. Together these data indicate that inhibin-A can antagonize TGFβ2 signaling in the context of two biologically relevant processes as well as in synthetic reporter assays, while having no effect on TGFβ1 signaling.

Inhibin antagonizes TGFβ2 signaling through betaglycan

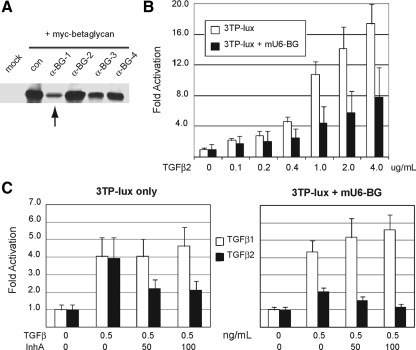

The differential effect of inhibin on TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 signaling suggests that inhibin exerts its effect via the unique dependence of TGFβ2 upon betaglycan, which TGFβ1 does not require, rather than via an interaction with the core TβRI/TβRII receptor complex shared by all TGFβ ligands. To determine whether the effects that we observed in Y1 cells were dependent upon betaglycan, we created four distinct short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors against mouse betaglycan (mU6-αBG nos. 1–4) and tested their ability to knock down expression of myc-tagged mouse betaglycan in 293 human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells (Fig. 4A). The mU6-αBG-1 vector showed particularly strong activity and was chosen for use in all further RNA interference (RNAi) experiments.

Figure 4.

TGFβ2 signaling and inhibin antagonism depend on betaglycan expression. A, 293-HEK cells were transfected with pCDNA3-betaglycan-myc alone or with one of four mU6-BG shRNA targeting vectors to validate the effectiveness of hairpin RNAs in decreasing betaglycan expression. Immunoblot analysis was used to indicate myc-betalycan expression in cells after cotransfection. Vector mU6-BG1 (lane 3, arrow) was the most effective at decreasing betaglycan expression and was used in subsequent assays. B, Luminescent assays for 3TP-lux reporter activation were performed in Y1 adrenocortical cells treated with increasing concentrations of TGFβ2 with or without the mU6-BG vector. C, Luminescent assays for 3TP-lux reporter activation were performed in Y1 adrenocortical cells treated with TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 either alone or in combination with recombinant inhibin-A. Experiments were repeated with cotransfection of the mU6-BG targeting vector to evaluate the effect of decreased betaglycan expression on signaling efficiency. For all reporter assays, 3TP-lux activity was normalized to signal from a CMV-Renilla luciferase cotransfected with 3TP-lux into Y1 cells. Data shown are triplicate measurements with error bars indicating standard deviations from the average of these three values. BG, Beta glycan.

Y1 cells transfected with mU6-αBG-1 show a significant decrease in sensitivity to TGFβ2, demonstrated by their decreased activation of the 3TP-lux reporter plasmid over a broad concentration of TGFβ2 ligand (Fig. 4B). At the normal EC50 of TGFβ2 (0.5ng/ml), cells transfected with mU6-αBG-1 display a 50% reduction in 3TP-lux activation, indicating that betaglycan expression has become a limiting factor in the ability of TGFβ2 to activate its downstream signaling pathway. Reduced expression of betaglycan has no effect on TGFβ1 signaling efficiency, consistent with the known dispensability of betaglycan coreceptor sites for TGFβ1 signaling.

Because RNAi-mediated knockdown with mU6-αBG-1 is unable to fully deplete cells of betaglycan, we asked 1) whether combining RNAi with inhibin would further decrease the sensitivity of Y1 cells to TGFβ2, and 2) whether this effect would remain specific to TGFβ2. To answer these questions, we transfected Y1 cells with mU6-αBG-1 and treated them with inhibin-A before TGFβ ligand stimulation and then compared this to inhibin-A or mU6-αBG-1 treatment alone. We found that combining inhibin-A treatment with betaglycan knockdown had an additive effect on TGFβ2 signaling, reducing the activation of 3TP-lux to almost background levels (Fig. 4C). As before, neither inhibin-A nor betaglycan depletion had any inhibitory effect on TGFβ1 activity in this assay (Fig. 4C). These results confirm that inhibin-A antagonism is indeed specific to TGFβ2 and also support the hypothesis that inhibin mediates this antagonism by modulating betaglycan-binding sites.

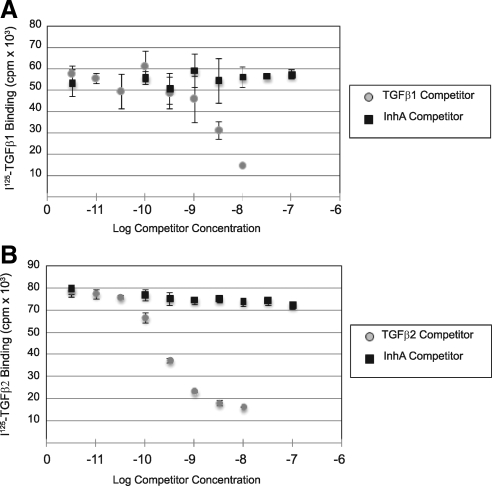

Inhibin cannot competitively displace TGFβ ligands from betaglycan

To better define the mechanism by which inhibin-A antagonizes TGFβ2 signaling, we first tested whether inhibin-A was able to physically displace TGFβ2 ligands from their binding sites on the Y1 cell surface. As a negative control, we also included TGFβ1 in these assays. Y1 cells robustly bind [125I]TGFβ1 and [125I]TGFβ2, which can both be displaced by increasing concentrations of cold ligand (Fig. 5, A and B). As expected from our 3TP-lux reporter assays, inhibin-A failed to displace [125I]TGFβ1 from the Y1 cell surface (Fig. 5A). Unexpectedly, however, inhibin-A also failed to complete [125I]TGFβ2 from the cell surface, even at concentrations that we had previously shown to functionally antagonize TGFβ2 signaling in multiple cellular assays (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that inhibin cannot directly prevent TGFβ2 binding to its surface receptors, including betaglycan, and suggest that inhibin instead functions by a mechanism that is distinct from how it antagonizes activin signaling.

Figure 5.

Inhibin-A cannot physically displace TGFβ ligands from cell surface-binding sites. Binding assays with [125I]TGF-β1 and [125I]TGF-β2 were performed on intact Y1 cells in 12-well plates. A, Binding of [125I]TGF-β1 to Y1 cells was competed with the indicated concentrations of unlabeled TGFβ1 ligand and unlabeled recombinant inhibin-A. B, Binding of [125I]TGF-β2 was similarly competed with the indicated concentrations of unlabeled TGFβ1 ligand and unlabeled recombinant inhibin-A.

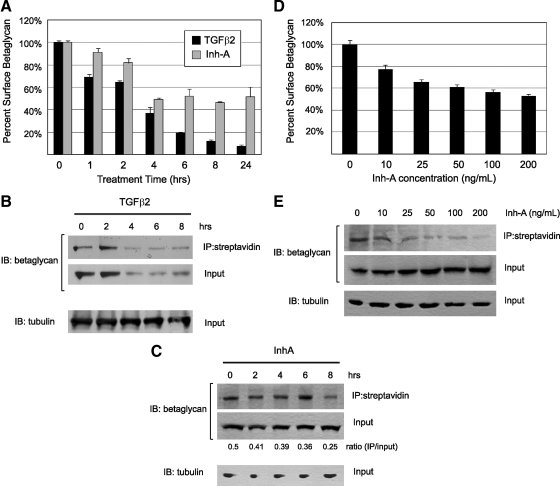

Inhibin reduces cell surface levels of betaglycan

Another possible mechanism by which inhibin could antagonize TGFβ2 signaling through betaglycan is the sequestration of betaglycan away from the cell surface into intracellular compartments. Previous studies have shown that TGFβ ligands induce the internalization of their cognate receptor complexes after prolonged stimulation, resulting in cellular desensitization to TGFβ signaling (25,26). To test this mechanism for inhibin, we developed a flow cytometry assay to measure the cell surface abundance of betaglycan. In this assay, an antibody targeted to the extracellular domain of betaglycan was used to label live, intact Y1 cells that had been treated with different concentrations or durations of ligand stimulation.

Consistent with the previous reports, we observed that TGFβ2 efficiently cleared betaglycan from the cell surface over an 8-h time course and maintained these reduced levels out to 24 h after treatment (Fig. 6A). To validate these data, we also performed cell surface biotinylation studies followed by immunoblot assays comparing biotinylated and total cellular betaglycan levels. These experiments confirm that TGFβ2 does indeed down-regulate the surface expression of betaglycan and also demonstrate that TGFβ2 promotes degradation of internalized betaglycan, because total cellular levels decrease in parallel with the loss of surface expression (Fig. 6B). These data parallel previous studies, which reported that once internalized in response to TGFβ ligands, the TGFβ receptor complex, including betaglycan, is trafficked to the lysosome for degradation (26).

Figure 6.

Inhibin-A induces betaglycan internalization. A, Y1 cells were treated with recombinant TGFβ2 (2 ng/ml) or inhibin-A (NIBSC, 100 ng/ml) in serum-free DMEM containing 0.05% BSA for the indicated times. Intact/live cells were labeled with an antibetaglycan antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescent signal strength was determined for each cell population. Signal from intact cells in each treated sample was normalized against signal from untreated Y1 cells, which was considered 100% surface occupation. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are displayed with error bars representing the standard deviations from these three replicate measurements. B, Surface proteins from Y1 cells treated for the indicated times with 2 ng/ml TGFβ2 were biotinylated and precipitated with streptavidin beads. Immunoblots for betaglycan and tubulin were performed on equal amounts of precipitate and 10% of the input lysates for each sample. C, Y1 cells treated for the indicated times with 100 ng/ml inhibin-A were biotinylated and treated as indicated above. Immunoblots for betaglycan and tubulin were performed on equal amounts of precipitate and 10% of the input lysates for each sample. Protein quantity was determined by densitometric analysis of band intensity, and the ratio of surface to total betaglycan is displayed beneath the lane of each experimental condition. D, Live/intact Y1 cells treated for 6 h with the indicated concentration of inhibin-A were labeled for surface betaglycan and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values shown were normalized as indicated above, with error bars representing standard deviation for three independent replicates. E, Y1 cells treated for 6 h with the indicated concentration of inhibin-A were biotinylated and treated as indicated above. Immunoblots for betaglycan and tubulin were performed on equal amounts of precipitate and 10% of the input lysates for each sample. IB, Immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Over a time course of 8 h, recombinant inhibin-A was similarly able to induce the down-regulation of surface betaglycan, albeit to a lesser extent than TGFβ2. By 4 h after treatment inhibin-A reduced surface betaglycan levels by 50%, which were not further decreased over a 24-h period of treatment (Fig. 6A). These results are notably consistent with our reporter assays, which required a preincubation time of 4–8 h with inhibin-A before treatment with TGFβ2 to elicit an inhibitory effect on 3TP-lux activation. Interestingly, however, surface biotinylation studies demonstrate that although inhibin-A reduces cell surface betaglycan levels, it does not reduce the amount of total cellular betaglycan (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that the internalization mechanism used by inhibin-A may be distinct from that of TGFβ2, as betaglycan is apparently recycled instead of being degraded.

To demonstrate that inhibin can induce betaglycan internalization in a dose-dependent fashion, we treated Y1 cells with increasing amounts of inhibin-A for a fixed period of 8 h. We found that increasing concentrations of inhibin-A from 5–100 ng/ml resulted in a progressive decrease in surface betaglycan, but that surface levels of betaglycan could not be decreased to less than 50% of untreated cells regardless of the concentration of inhibin A used (Fig. 6, D and E). As before, the level of total cellular betaglycan remained unchanged regardless of the concentration of inhibin-A used (Fig. 6E), supporting the hypothesis that inhibin promotes the recycling of betaglycan back to the cell surface after internalization, instead of targeting it for degradation.

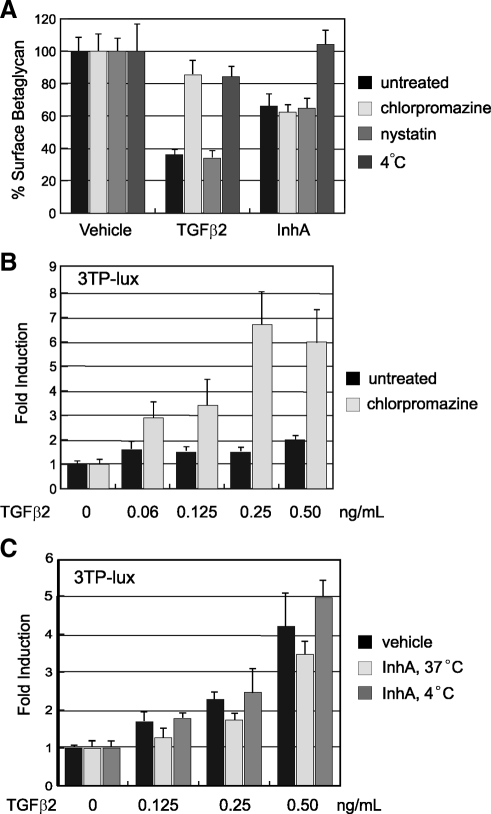

Inhibin and TGFβ2 promote endocytosis of betaglycan by distinct mechanisms

Cell surface receptor proteins are internalized by distinct endocytic mechanisms that are either clathrin dependent or clathrin independent. The latter mechanism is dependent upon cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains such as cavaolae or lipid rafts (27). Although all mechanisms of endocytosis are inhibited by decreasing cellular temperature to 4 C, clathrin-dependent mechanisms can be specifically blocked with the drug chlorpromazine, whereas clathrin-independent mechanisms can be inhibited with nystatin (28).

To evaluate the endocytic mechanisms used by TGFβ2 and inhibin-A to promote betaglycan internalization, we treated cells for 6 h with each ligand under normal culture conditions (5% CO2, 37 C) and then analyzed surface betaglycan levels by flow cytometry. These experiments were also performed at reduced temperature (4 C) or in the presence of nystatin (25 μg/ml) or chlorpromazine (25 μm) to inhibit endocytosis. TGFβ2-mediated internalization of betaglycan is blocked at 4 C and by chlorpromazine, but not nystatin, suggesting that TGFβ2 induces clathrin-dependent internalization and degradation of betaglycan (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, internalization of betaglycan by inhibin-A was inhibited at 4 C but was not blocked by either drug.

Figure 7.

Inhibin-A promotes endocytosis of betaglycan by a clathrin-independent mechanism. A, Y1 cells were treated with recombinant TGFβ2 (2 ng/ml) or inhibin-A (NIBSC, 100 ng/ml) in serum-free DMEM containing chlorpromazine (25 μm), nystatin (25 μg/ml), or incubation at 4 C for 6 h. Intact/live cells were labeled with an antibetaglycan antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescent signal strength was determined for each cell population, and was normalized against the value from untreated Y1 cells, which was considered 100% surface occupation. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data is displayed with error bars representing the standard deviations from these three replicate measurements. B, Luminescent assays for 3TP-lux reporter activation were performed in Y1 adrenocortical cells treated for 16 h with 25 μm chlorpromazine and the indicated concentration of TGFβ2. 3TP-lux activity was normalized to the luminescent signal from a constitutively expressed pCMV-Renilla reporter vector that was cotransfected with 3TP-lux into Y1 cells. Values for three independent replicates are shown with error bars indicated standard deviation. C, Luminescent assays for 3TP-lux reporter activation were performed in Y1 adrenocortical cells treated for 8 h with 100 ng/ml recombinant inhibin-A at either 37 C or 4 C, followed by 16 h with the indicated concentration of TGFβ2 at 37 C. 3TP-lux activity was normalized as above, with error bars indicated standard deviation.

Because clearance of betaglycan from the cell surface results in cellular desensitization to TGFβ2 signaling, it would be predicted that forced retention of betaglycan at the cell surface would enhance TGFβ2 signaling over extended periods of time. To test this hypothesis we treated Y1 cells with low concentrations of TGFβ2 for 16 h in the presence or absence of 25 μm chlorpromazine and analyzed TGFβ2 signaling strength with the 3TP-lux reporter. These experiments demonstrate that inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis enhances TGFβ2 signaling by preventing the internalization of TGFβ receptor complexes, including betaglycan, from the cell surface (Fig. 7B). More critically, they also reinforce the importance of surface receptor abundance in the regulation of TGFβ2 signal strength.

To determine whether inhibiting endocytosis similarly alters the ability of inhibin to regulate TGFβ2 signaling, we performed inhibin competition assays at temperatures that were permissive (37 C) or nonpermissive (4 C) for endocytosis. In these assays, Y1 cells that had been previously transfected with the 3TP-lux reporter were pretreated with recombinant inhibin-A at 37 C or 4 C for 8 h and then subsequently treated with different doses of TGFβ2 for 16 h at 37 C. Whereas pretreatment with inhibin-A at the permissive temperature decreased TGFβ2 activation of 3TP-lux, pretreatment at the nonpermissive temperature had no effect compared with cells that were not exposed to inhibin-A (Fig. 7C). These data demonstrate that functional endocytosis is required for inhibin to antagonize TGFβ2 signaling and support the hypothesis that inhibin regulates TGFβ2 by modulating levels of surface betaglycan.

Discussion

Studies of inhibin α-subunit knockout (Inha−/−) mice largely demonstrate that the central role of inhibin is to limit activin signaling to the anterior pituitary and gonads. Inha−/− mice display elevated FSH levels and develop gonadal sex cord-stromal tumors of granulosa or Sertoli cell origin (12). Removal of the gonads to prevent tumor formation, however, invariably leads to adrenocortical tumorigenesis. Interestingly, the phenotype of adrenocortical tumors in Inha−/− mice is largely indistinguishable from that of ovarian tumors, which are primarily composed of mixed lineage sex cord-stromal cells that produce high levels of estradiol and activins (11,15,16). Because this cellular identity is not endogenous to the adrenal gland, these findings suggest a novel role for inhibin in the regulation of adrenocortical cell specification (11). Whether this role is mechanistically separate from its role in the gonads has been unclear to this point.

Based on the results of this study, we propose that inhibin suppresses the aberrant respecification of adrenocortical cells by antagonizing TGFβ2 signaling. This inhibitory role is compromised in Inha−/− mice that develop adrenocortical tumors in response to gonadectomy. Although TGFβ2 is similarly up-regulated in the adrenal cortex of gonadectomized wild-type mice or bLH-βCTP transgenic mice, we suggest that signaling by TGFβ2 in these animals is antagonized by inhibin to prevent the progression of abnormally specified cells into frank tumors. In the absence of inhibin, these misspecified cells continue to proliferate and eventually develop into sex cord-stromal cell tumors, which produce activins to sustain Smad3 activation and proliferation in a classical autocrine signaling loop. This two-step model would be expected to be unique to the adrenal cortex, because the first step (i.e. respecification of adrenal progenitor cells into sex cord-stromal cells) is unnecessary in the gonad, where the correct tumor cell identity is endogenously present.

In support of this model, we show that high inhibin levels can indeed functionally antagonize TGFβ2 signaling in vitro, both at the level of target genes and Smad3 activation. As opposed to its interaction with activin, however, the interaction of inhibin with TGFβ2 does not appear to be one of direct competition for receptor binding, because inhibin fails to displace radiolabeled TGFβ ligands from the cell surface of Y1 adrenal cells. A potential explanation for these data is the recent finding that TGFβ ligands bind to two separate sites on betaglycan, only one of which is also bound by inhibin (29). As such, it would be expected that inhibin would be unable to fully displace TGFβ ligands from betaglycan.

Instead, we propose that inhibin specifically antagonizes TGFβ2 signaling in the adrenal cortex by stripping the cell surface of high-affinity betaglycan coreceptor sites, which are required for efficient TGFβ2 signaling (30,31). Consistent with this hypothesis, our data demonstrate that depletion of surface betaglycan, either by RNAi or inhibin, leads to decreased TGFβ2 responsiveness in Y1 cells. Because the removal of surface betaglycan by inhibin is blocked by lowering cells to 4 C, it appears that inhibin binding to betaglycan induces its endocytosis. Although the precise mechanism that drives this process awaits additional study, it is clear that it does not involve trafficking to the lysosome, because betaglycan is not degraded in response to inhibin. Interestingly, a similar mechanism for desensitization of cells to TGFβ family signaling has also been described in endothelial cells, which internalize both the type III receptor endoglin and TβRII in response to thrombin signaling (32).

Our data also demonstrate that internalization of betaglycan by inhibin occurs by a distinct mechanism compared with internalization induced by TGFβ2, because inhibin-mediated endocytosis is insensitive to the clathrin inhibitor chlorpromazine, which completely blocks TGFβ2-mediated endocytosis. Additionally, TGFβ2 induces degradation of betaglycan in a time-dependent manner, which does not occur after inhibin treatment regardless of the concentration or time used. That these two mechanisms are distinct is not surprising, however, because TGFβ-mediated endocytosis of betaglycan has previously been shown to depend upon phosphorylation of the short intracellular domain of betaglycan by TβRII (25). Because inhibins are unable to activate any Type I/Type II receptor complexes, this endocytic mechanism is unlikely to occur during inhibin binding to betaglyan. Both the route and molecular machinery required for inhibin to induce endocytosis of betaglycan require further investigation.

The relevance of our findings to human disease is highlighted by gene expression-profiling studies of human adrenocortical tumors (33,34). These studies identified two distinct cohorts of genes, the opposing expression patterns of which correlate well with the rate tumor recurrence in patients. The first cluster of genes, the up-regulation of which correlates with an increased rate of tumor recurrence, includes both TGFβ2 and TGFβRI (Alk5), whereas the second cluster of genes, the down-regulation of which correlates with an increased rate of tumor recurrence, includes both Inhα and betaglycan. It is notable that these specific molecular components of the TGFβ-signaling pathway correspond to those we have identified as being central to adrenocortical tumor initiation in Inha−/− mice. Together with our findings, these data suggest that the TGFβ pathway plays an important role in both human and mouse adrenocortical tumorigenesis, and that the novel molecular interaction between inhibin and TGFβ2 that we have described above may be conserved in the human adrenal cortex.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animal treatment and care

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with institutionally approved and current animal care guidelines from University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Generation and genotyping of mice with a targeted deletion of the α-inhibin gene (Inha−/−) and mice harboring the bLH-βCTP transgene under control of the bovine LH α-subunit promoter have been described previously (12,35). For the adrenal tumor studies, surgical gonadectomies were performed at the age of 5 wk. Mice were euthanized upon indication of end-stage disease, characterized by severe weight loss, hunched posture, and sunken eyes, as has been previously described (11).

RT-PCR and real-time PCR

Tissues were removed, cleaned, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were lysed in Trizol reagent using an electric tissue homogenizer, and total RNA was collected according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. In the case of cultured cells, the total cell pellet was washed once with PBS and then directly harvested in Trizol reagent with vigorous pipetting to homogenize the cellular lysates. Total RNA was treated with deoxyribonuclease (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) to remove any residual genomic DNA and was quantified by UV spectrometry. One microgram of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the iScript kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The final cDNA product was purified and eluted in 50 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer using PCR purification columns (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA). This product (1 μl) was used as template for all subsequent quantitative PCRs.

For quantitative, real-time PCR analysis of mRNA transcript abundance, PCRs were made up using a 2× SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) along with gene-specific primers, and thermocycling was performed in the ABI 7300 thermocycler system (Applied Biosystems). Each quantitative measurement was normalized to Rox dye as an internal standard and performed in triplicate. Transcript abundance was normalized to the average Ct value of mouse acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein (Arbp) for each sample. For mRNA quantitation directly from adrenal or tumor tissue, measurements (n ≥ 4) were performed with n being the number of individual tissue samples from different animals.

Primary cell culture

Adrenals from wild-type mice and adrenal tumors from Inha−/− mice were removed, cleaned, and decapsulated to reduce contamination of tumor cell cultures with fibrotic capsular cells. Tissue was briefly rinsed in sterile PBS and then diced in 2 ml of DMEM:F12 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 1× penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone solution (Invitrogen), 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and 1 mg/ml deoxyribonuclease I (Sigma) to dissociate cells. The digest was incubated in a tissue culture incubator at 37 C for 45 min with vigorous pipetting every 15 min to disperse aggregated cells. Separated cells were then washed in primary culture media [DMEM:F12 media with 1× penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone and 0.05% BSA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and pelleted for 5 min at 1500 rpm. After a second round of washing, the cells were counted on a hemocytometer and plated evenly to fibronectin-coated six-well Primaria plates in primary culture media with or without treatment as indicated. After 24 h incubation, the cells were washed with cold PBS and harvested for immunoblotting with cold lysis buffer or with Trizol reagent for RT-PCR as indicated above.

Immunoblotting

Adrenals or adrenal tumors were removed, dissected from surrounding adipose and connective tissue, and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein lysates were collected by briefly sonicating frozen tissues in lysis buffer (40 mm HEPES, 120 mm sodium chloride, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mm sodium glycerophosphate, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm sodium fluoride, 0.5 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), followed by 1-h rotation at 4 C to solublize proteins. Soluble protein was collected from centrifuged total lysates and quantified by Bradford assay. SDS-PAGE was performed on 9–10% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels loaded with 10–40 μg of protein per sample, and separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a semidry transfer unit. After transfer, membranes were blocked 1 h in 4% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), and then incubated overnight at 4 C with primary rabbit antibodies against TβRI/Alk5 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), TβRII (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), TβRIII/betaglycan (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), Smad3 (1:1000; Zymed Laboratories, South San Franciso, CA) or phospho-Smad3 (1:500, gift from Dr. Michael Reiss, Cancer Institute of New Jersey), or primary mouse antibodies against β-actin (1:5000, Sigma). The next day, membranes were washed three times for 5–10 min in TBST and then incubated with HRP-labeled goat antirabbit or antimouse secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After three more washes in TBST, membranes were incubated for 2–5 min in West Dura ECL reagent (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), and then exposed to film for detection.

In situ hybridization

Ovaries, testis, and adrenals were collected at indicated ages and fixed for 2–3 h in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS. Tissues were dehydrated in graded ethanols and methyl salicylate, and embedded in paraffin before sectioning. Sections were cut at 6 μm thickness and floated on prewarmed and moistened glass slides to remove any surface inconsistencies in the sections. Water was removed from under the sections by gentle aspiration, and the sections were dried overnight at 37 C to promote adherence to the slides. After drying, sections were deparaffinized in xylenes and rehydrated in graded ethanols followed by deionized water. In situ hybridization was performed using a digoxigenin-labeled probe to TGFβ2 (Roche) mRNA according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The probe was detected with overnight exposure to nitro blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche) at a 1:40 dilution in the indicated sample detection buffer.

Generation of betaglycan shRNA plasmid vectors

The mU6-pro vector (obtained from Dr. David Turner, University of Michigan) contains a multiple cloning site that accepts annealed double-stranded oligos of 21-bp homology to the target gene in forward and reverse orientation linked by a 5-bp bridge to create shRNAs (36). We generated four such targeting sequences using predictive software generated by the laboratory of Dr. Jack Lin (http://www.sinc.sunysb.edu/Stu/shilin/rnai.html) and cloned each of them into mU6-pro to generate mouse betaglycan shRNA vectors 1–4. Each of these vectors (1 μg/10-cm plate) was cotransfected into 293 HEK cells with a vector containing a C-terminal myc-tagged mouse betaglycan cloned into pCDNA3 (1 μg/10-cm plate). Protein lysates were harvested 48 h after transfection and subjected to immunoblotting for expression of myc-betaglycan as indicated above. Detection of the myc epitope was performed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-myc antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology). Vector 1 (Fig. 4A) was chosen for further studies based on its superior efficiency at depleting betaglycan levels.

Y1 cell culture and transfection

Y1 mouse adrenocortical cells obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 7.5% horse serum, 2.5% bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and fungizone (Invitrogen), and were plated exclusively on Primaria cultureware (Corning, Inc., Corning NY). For transient transfection assays, Y1 cells were plated at a density of 6 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates and transfected using Fugene6 reagent (Roche) at a 1:3 ratio with total plasmid DNA. The 3TP-lux reporter vector (obtained as a gift from Dr. Colin Duckett, University of Michigan) was transfected in triplicate at a concentration of 100 ng/well 24–48 h before reporter assays along with a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-LacZ transfection control plasmid at a concentration of 30 ng/well. In assays using shRNA-mediated knockdown of betaglycan, cells were transfected with 150 ng/well of the mU6-BG vector. Cells were pre-treated for 6–8 h with recombinant inhibin-A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at indicated concentrations before addition of recombinant TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 peptide (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), which was added to cells 16 h before harvest of cell lysates for luminescent assays. The endocytosis inhibitors chlorpromazine hydrochloride (Sigma) and nystatin (Sigma) were dissolved in water immediately before use at the concentrations indicated in the text and figure legends.

Luminescent reporter assays

Y1 cell lysates were harvested from 24-well plates with 100 μl/well of 1× Reporter Lysis Buffer (Applied Biosystems) and rotation at room temperature for 15 min. Luciferase expression was quantified from 10 μl of lysates using firefly luciferase substrate (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), whereas β-galactosidase expression from the CMV-LacZ transfection control plasmid was measured from 5 μl of lysates with Galacton luminescent substrate (Applied Biosystems). Measurements for both luciferase and β-galactosidase were performed on a Veritas luminometer (Turner Biosystems) using the manufacturer’s recommended settings. Normalized values were calculated as the ratio of luciferase/β-galactosidase from triplicate measurements of each experimental condition. Each experiment was performed three to four times to ensure reproducibility, and error bars shown are standard deviations of representative experiments.

Radiolabeled ligand-binding assays

Y1 cells were grown in DMEM containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum and 7.5% horse serum in Primaria (Invitrogen) tissue culture plates. For binding assays, Y1 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells per well in poly-d-lysine coated 12-well plates and allowed to recover overnight. Binding assays with [125I]TGF-β1 and [125I]TGF-β2 was performed on intact cells in 12-well plates. For binding, wells were washed in binding buffer (DMEM supplemented with 1% BSA) and preincubated with 2× stock concentrations of unlabeled TGFβ or inhibin-A competitor as shown for 5 min, followed by addition of 5 × 105 cpm per well of [125I]TGF-β1 or [125I]TGF-β2 as indicated. Wells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with gentle agitation in a total volume of 500 μl. Wells were then washed three times in binding buffer, solubilized in 500 μl 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and [125I]binding in each well was determined using a γ-counter.

Flow cytometric betaglycan internalization assays

Y1 cells were plated to six-well plates (8.0 × 104 cells per well) and were treated with the indicated concentrations of recombinant TGFβ2 (Peprotech) or inhibin-A (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, Hertfordshire, UK) in serum-free DMEM containing 0.05% BSA for the indicated times. Cells were washed with PBS, scraped into ice-cold Versene (Invitrogen), and then washed two times with wash buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide) to stabilize membrane proteins. Cells were incubated in a 1:50 dilution of rabbit anti-betaglycan antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies) in wash buffer at 4 C with constant rotation for 30 min. Cells were then washed two times with wash buffer and then incubated in a 1:250 dilution of allophycocyanin-coupled goat antirabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at 4 C with constant rotation for an additional 30 min. Finally, cells were washed two times with wash buffer and resuspended in wash buffer containing 500 μg/ml of propidium iodide. The cells were analyzed with a four-color FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to quantify the mean fluorescent signal of each cell population. The mean value for each condition was normalized against signal from untreated Y1 cells, which was considered 100% surface occupation under normal homeostatic conditions. Fluorescent signal from internalized betaglycan was removed by gating out cells that stained positive for propidium iodide due to compromised plasma membranes. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are displayed as the average of these replicate measurements with error bars representing the standard deviation.

Membrane-labeling betaglycan internalization assays

Y1 cells were seeded to 10-cm plates to achieve 70–90% confluency on the day of the experiment. The following day, cells were washed two times with PBS and refed with serum-free DMEM containing 0.05% BSA for a minimum of 16 h before inhibin treatment. Cells were then treated with the indicated concentration of recombinant human inhibin-A (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control) or TGFβ2 (Peprotech) for the indicated period of time. After peptide treatment, each plate of cells was washed two times with ice-cold PBS and incubated on ice. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated with the EZ-Link Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit (Pierce Chemical Co.) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Briefly, cells were treated with Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin cross-linking agent (dissolved in PBS) for 30 min at 4 C with constant rotation. The cross-linking reaction was quenched and cells were scraped into ice-cold TBS. The cells were then pelleted, washed with ice-cold TBS, and lysed in M-PER protein extraction buffer (Pierce). Soluble lysates were incubated with 50 μl of preequilibrated neutravidin beads for 1 h at room temperature to precipitate out biotinylated cell surface proteins. The beads were pelleted and washed three times with ice-cold lysis buffer, and bound protein was eluted with sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing lysis buffer and boiling for 5 min. The total volume of precipitated protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were probed overnight with antibetaglycan antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) and detected with a horseradish peroxidase-coupled antirabbit secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Loading was normalized to 10% input from each of the lysates, and blots were quantified using a ChemiDoc imaging station equipped with a charge-coupled device camera and QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Acknowledgments

The Inha−/− strain of mice was generated and provided by Dr. Martin Matzuk (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) and the bLH-βCTP mice were generated and provided by Dr. John Nilson (Washington State University, Pullman, WA). The phospho-Smad3 antibody was provided by Dr. Michael Reiss (Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ). The mU6-pro shRNA vector was provided by Dr. David Turner (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI).

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Clayton Medical Research Foundation, Inc.; by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK062027 (to G.H.); and by an award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5P01HD013527-28). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: B.L. and E.W. have nothing to declare. G.H. consults for Orphagen Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA) and Embera NeuroTherapeutics, Inc. (Shreveport, LA). W.V. is a cofounder, consultant, equity holder and member of the Board of Directors for Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. (San Diego, CA) and Acceleron Pharma, Inc. (Cambridge, MA), W.V. is also a Clayton Medical Research Foundation, Inc., Senior Investigator and is the Helen McLoraine Professor of Molecular Neurobiology.

First Published Online December 16, 2009

Abbreviations: ActRII, Activin-type II receptor; CMV, cytomegalovirus; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; HEK, human embryonic kidney; LHR, LH receptor; PKA, protein kinase A; RNAi, RNA interference; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; TBST, TBS-Tween 20.

References

- Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM 2002 Genetic analysis of the mammalian transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Endocr Rev 23:787–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ 2002 Genetic dissection of mammalian fertility pathways. Nat Cell Biol 4(Suppl):s41–s49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RW, Thompson TB, Jardetzky TS, Woodruff TK 2004 Molecular biology of inhibin action. Semin Reprod Med 22:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier JF, Findlay JK 2001 Roles of activin and its signal transduction mechanisms in reproductive tissues. Reproduction 121:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J, Seoane J, Wotton D 2005 Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev 19:2783–2810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ, Chapman SC, Woodruff TK 2001 Mechanisms of inhibin signal transduction. Recent Prog Horm Res 56:417–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun JJ, Vale WW 1997 Activin and inhibin have antagonistic effects on ligand-dependent heteromerization of the type I and type II activin receptors and human erythroid differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 17:1682–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PC, Bilezikjian LM, Vale W 2002 Antagonism of activin by inhibin and inhibin receptors: a functional role for betaglycan. Mol Cell Endocrinol 188:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheifetz S, Hernandez H, Laiho M, ten Dijke P, Iwata KK, Massagué J 1990 Distinct transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor subsets as determinants of cellular responsiveness to three TGF-β isoforms. J Biol Chem 265:20533–20538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier JF, Farnworth PG, Findlay JK, Ooi GT 2002 Transforming growth factor-β modulates inhibin A bioactivity in the LβT2 gonadotrope cell line by competing for binding to betaglycan. Mol Endocrinol 16:2754–2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Mather JP, Krummen L, Lu H, Bradley A 1994 Development of cancer cachexia-like syndrome and adrenal tumors in inhibin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:8817–8821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A 1992 α-Inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature 360:313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hefnawy T, Zeleznik AJ 2001 Synergism between FSH and activin in the regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and cyclin D2 expression in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology 142:4357–4362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miró F, Hillier SG 1996 Modulation of granulosa cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and differentiation by activin. Endocrinology 137:464–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looyenga BD, Hammer GD 2006 Origin and identity of adrenocortical tumors in inhibin knockout mice: implications for cellular plasticity in the adrenal cortex. Mol Endocrinol 20:2848–2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuschlein F, Looyenga BD, Bleasdale SE, Mutch C, Bavers DL, Parlow AF, Nilson JH, Hammer GD 2003 Activin induces x-zone apoptosis that inhibits luteinizing hormone-dependent adrenocortical tumor formation in inhibin-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 23:3951–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Palapattu G, Wang P, Woodruff TK, Boime I, Byrne MC, Matzuk MM 1999 Transgenic models to study gonadotropin function: the role of follicle-stimulating hormone in gonadal growth and tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol 13:851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Wang Y, Matzuk MM 1996 Gonadotropins are essential modifier factors for gonadal tumor development in inhibin-deficient mice. Endocrinology 137:4210–4216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kero J, Poutanen M, Zhang FP, Rahman N, McNicol AM, Nilson JH, Keri RA, Huhtaniemi IT 2000 Elevated luteinizing hormone induces expression of its receptor and promotes steroidogenesis in the adrenal cortex. J Clin Invest 105:633–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looyenga BD, Hammer GD 2007 Genetic removal of Smad3 from inhibin-null mice attenuates tumor progression by uncoupling extracellular mitogenic signals from the cell cycle machinery. Mol Endocrinol 21:2440–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley-Kallesen ML, Kelly D, Rizzino A 1999 Transcriptional regulation of the transforming growth factor-β2 promoter by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) and activating transcription factor-1 (ATF-1) is modulated by protein kinases and the coactivators p300 and CREB-binding protein. J Biol Chem 274:34020–34028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ET, Forti FL, Rocha KM, Moraes MS, Armelin HA 2004 Molecular mechanisms of cell cycle control in the mouse Y1 adrenal cell line. Endocr Res 30:503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherradi N, Chambaz EM, Defaye G 1995 Type β1 transforming growth factor is an inhibitor of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isomerase in mouse adrenal tumor cell line Y1. Endocr Res 21:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M, Oursler MJ, Rasmussen K, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC 1995 TGF-β regulation of nuclear proto-oncogenes and TGF-β gene expression in normal human osteoblast-like cells. J Cell Biochem 57:52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Kirkbride KC, How T, Nelson CD, Mo J, Frederick JP, Wang XF, Lefkowitz RJ, Blobe GC 2003 β-Arrestin 2 mediates endocytosis of type III TGF-β receptor and down-regulation of its signaling. Science 301:1394–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL 2003 Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-β receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol 5:410–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy C, Wrana JL 2005 Clathrin- and non-clathrin-mediated endocytic regulation of cell signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:112–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AI 2008 Pharmacological inhibition of endocytic pathways: is it specific enough to be useful? Methods Mol Biol 440:15–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiater E, Harrison CA, Lewis KA, Gray PC, Vale WW 2006 Identification of distinct inhibin and transforming growth factor β-binding sites on betaglycan: functional separation of betaglycan co-receptor actions. J Biol Chem 281:17011–17022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar S, Mahooti-Brooks N, Centrella M, McCarthy TL, Madri JA 1995 Expression of transforming growth factor type III receptor in vascular endothelial cells increases their responsiveness to transforming growth factor β 2. J Biol Chem 270:13567–13572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenvers KL, Tursky ML, Harder KW, Kountouri N, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Grail D, Small C, Weinberg RA, Sizeland AM, Zhu HJ 2003 Heart and liver defects and reduced transforming growth factor β2 sensitivity in transforming growth factor β type III receptor-deficient embryos. Mol Cell Biol 23:4371–4385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Low B, Rutherford SA, Hao Q 2005 Thrombin induces endocytosis of endoglin and type-II TGF-β receptor and down-regulation of TGF-β signaling in endothelial cells. Blood 105:1977–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Fraipont F, El Atifi M, Cherradi N, Le Moigne G, Defaye G, Houlgatte R, Bertherat J, Bertagna X, Plouin PF, Baudin E, Berger F, Gicquel C, Chabre O, Feige JJ 2005 Gene expression profiling of human adrenocortical tumors using complementary deoxyribonucleic acid microarrays identifies several candidate genes as markers of malignancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1819–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TJ, Thomas DG, Kuick R, Lizyness M, Misek DE, Smith AL, Sanders D, Aljundi RT, Gauger PG, Thompson NW, Taylor JM, Hanash SM 2003 Distinct transcriptional profiles of adrenocortical tumors uncovered by DNA microarray analysis. Am J Pathol 162:521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risma KA, Clay CM, Nett TM, Wagner T, Yun J, Nilson JH 1995 Targeted overexpression of luteinizing hormone in transgenic mice leads to infertility, polycystic ovaries, and ovarian tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:1322–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JY, DeRuiter SL, Turner DL 2002 RNA interference by expression of short-interfering RNAs and hairpin RNAs in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:6047–6052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]