Abstract

Context: Leptin regulates energy homeostasis by suppressing food intake; however, its role in energy expenditure and fat oxidation remains uncertain in humans.

Objective: The aim of the study was to assess 24-h energy metabolism before and after weight loss induced by leptin treatment in congenital leptin-deficient subjects or low-calorie diet in controls.

Design and Patients: We measured 24-h energy expenditure, 24-h fat oxidation, and body fat in three null homozygous leptin-deficient obese adults before and after weight loss induced by a 19-wk leptin replacement period (0.02–0.04 mg/kg/d). The same measures were performed in three obese controls pair-matched for sex, age, and weight loss induced by a 10- to 21-wk low-calorie diet. Measurements were preceded for 1 wk of weight stabilization. Energy expenditure was adjusted for fat-free mass, fat mass, sex, and age based on a reference population (n = 842; R2 = 0.85; P < 0.0001). Similarly, fat oxidation was adjusted for fat-free mass, percentage body fat, energy balance, and diet composition during the 24-h respiratory chamber stay (R2 = 0.38; P < 0.0001).

Results: Before weight loss, congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects had similar energy expenditure. However, after weight loss (∼15 kg), controls had energy expenditures lower than expected for their new weight and body composition (−265 ± 76 kcal/d; P = 0.04), whereas leptin-treated subjects had values not different from the reference population (−128 ± 119 kcal/d; P = 0.67). Before weight loss, fat oxidation was similar between groups. However, after weight loss, leptin-treated subjects had higher fat oxidation than controls (P = 0.005) and higher than the reference population (P = 0.0001).

Conclusion: In congenital leptin-deficient subjects, leptin replacement prevented the decrease in energy expenditure and fat oxidation often observed after weight loss.

Leptin replacement prevents the decrease in energy expenditure and fat oxidation after weight loss in congenital leptin-deficient subjects.

Leptin, the product of the ob gene, is secreted from fat cells in proportion to the size of adipose depots (1). Leptin binds to its receptors in the brain where it modulates food intake behavior (2). Leptin-deficient animals and humans are characterized by increased appetite and food intake resulting in severe obesity. Leptin also enhances in vitro fat oxidation via AMP-activated protein kinase (3).

In response to body weight loss, overweight/obese patients experience a relative hypoleptinemic state accompanied by a fall in energy expenditure (EE) independent of changes in fat-free mass and fat mass (4,5). This lower EE in humans maintaining a reduced body weight was prevented when leptin was replaced (6). Similarly, in two morbidly obese congenitally leptin-deficient children treated with leptin, basal and total EEs were “normal” after weight loss (7). These data suggest that leptin may have a thermogenic effect in humans.

We measured 24-h EE and 24-h fat oxidation in a respiratory chamber in three congenital leptin-deficient obese adults before and after leptin replacement therapy. Results were compared with those obtained in three obese control volunteers matched for sex, age, and weight loss induced by a low-calorie diet. Such design represents a unique experimental paradigm in which congenital leptin-deficient subjects lose weight in the presence of increased plasma leptin concentration, whereas control obese individuals lose weight with a lowering in plasma leptin concentration. Results were also compared with a reference population in which 24-h energy metabolism data were available.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Three obese individuals (age, 32.9 ± 6.2 yr; body mass index, 49.8 ± 4.6 kg/m2) having congenital leptin deficiency due to a nonconservative missense leptin gene mutation (Cys-to-Thr in codon 105) were compared with three obese controls pair-matched for sex and age (age, 32.4 ± 5.7 yr; body mass index, 44.4 ± 5.1 kg/m2) (Table 1). Congenital leptin-deficient and female control subjects were evaluated in 2001–2002. A nondiabetic control volunteer with similar anthropometric characteristics as observed in his congenital leptin-deficient counterpart was difficult to identify. Metabolic assessment was finally conducted in 2008. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, and all six volunteers provided written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Control volunteers were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers. In addition, we compared energy metabolism of our six participants against a reference population (328 females and 514 males; age, 31 ± 12 yr; weight, 90 ± 25 kg; and body fat, 29 ± 11%) in which 24-h respiratory chamber measurements were available under energy balance conditions.

Table 1.

Individual characteristics of congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects

| Congenital leptin-deficient group

|

Control group

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | Weight (kg) | Body fat (%) | Δ Weight (kg) | Δ Fat (kg) | Age (yr) | Weight (kg) | Body fat (%) | Δ Weight (kg) | Δ Fat (kg) | |

| Male | 26 | 133 | 43.6 | −15.8 | −10.3 | 27 | 120 | 36.9 | −11.4 | −9.9 |

| Female 1 | 34 | 104 | 45.7 | −14.5 | −11.8 | 31 | 106 | 43.4 | −15.7 | −10.6 |

| Female 2 | 39 | 132 | 47.3 | −16.3 | −13.2 | 39 | 128 | 49.4 | −17.3 | −9.6 |

Study design

Congenital leptin-deficient subjects were assessed before and after a 19-wk weight loss period induced by recombinant methionyl human leptin sc, once daily between 1800 and 2000 h (0.02–0.04 mg/kg/d; Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA). Controls were also assessed before and after weight loss by a 9- to 20-wk low-calorie diet (890 kcal/d, HEALTH ONE; Health and Nutrition Technology, Carmel, CA) to achieve a weight loss similar to that observed in congenital leptin-deficient subjects. Body fat mass and fat-free mass were assessed on a Hologic dual energy x-ray absorptiometer (QDR 4500; Hologic, Waltham, MA).

Energy metabolism measures

Twenty-four-hour EE and 24-h respiratory quotient were determined in a whole-room respiratory calorimeter as previously described (8). All the measurements were performed after a 1-wk body weight stabilization period at baseline (−1.2 ± 1.4 kg) and after weight loss (0.1 ± 0.9 kg). Twenty-four hour EE, fat oxidation, protein oxidation, and carbohydrate oxidation were calculated in conditions of energy balance achieved by an algorithm to balance intake and expenditure within the day of measurement (9). The diet provided 50% carbohydrates, 35% fat, and 15% protein and was served according to a fixed schedule. Physical activity level during the metabolic chamber stay was determined by the 24-h to sleeping EE ratio.

Plasma leptin

When participants left the metabolic chamber, blood was obtained to measure fasting plasma leptin concentration (Linco Research Immunoassay, St. Charles, MO).

Statistical analysis

A predictive equation of 24-h EE was derived from the reference population using regression analysis taking into account fat-free mass, fat mass, sex, and age [24-h EE in kcal/d = 1031 + 9.9 × fat mass (kilograms) + 18.1 × fat-free mass (kilograms) − 2.6 × age (years) − 222 (females); R2 = 0.85; P < 0.0001]. From this equation, predicted 24-h EE was calculated for each study participant, and the difference between the measured and predicted values (residual) was calculated. A similar analysis was performed to calculate predicted 24-h fat oxidation considering fat-free mass, the food quotient, energy balance, and body fat content [24-h fat oxidation in grams per day = 1482 + 1.31 × fat-free mass (kilograms) − 1660 × food quotient − 0.53 × energy balance (%) + 0.51 × body fat (%); R2 = 0.38; P < 0.0001]. The food quotient (FQ) was calculated as follows: FQ = [(CHO% × 1.00) + (FAT% × 0.707) + (PRO% × 0.83)]; where CHO%, FAT%, and PRO% are the proportions of the energy coming from carbohydrate, fat, and protein, respectively. Energy balance was calculated as the 24-h energy intake to 24-h EE ratio multiplied by 100. Such analytical method using residuals is more appropriate because data normalization using metabolic rate divided by fat-free mass is erroneous (10). Differences between congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects and the reference population were tested using ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test. Values are presented as mean ± sd.

Results

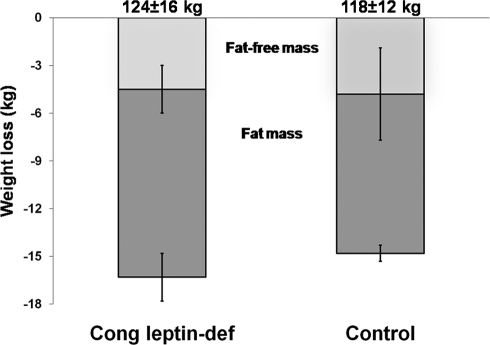

After starting replacement with leptin, congenital leptin-deficient subjects easily lost body weight as previously reported (11), whereas controls on a low-calorie diet lost similar amounts of weight by study design but at the expense of much willpower (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Plasma leptin concentration was below detection limit (0.5 ng/ml) in congenital leptin-deficient subjects before treatment and was 24.0 ± 5.6 ng/ml after leptin treatment at the time of the second chamber measurement. In controls, plasma leptin concentration before weigh loss was 34.2 ± 17.4 ng/ml and decreased to 28.7 ± 18.3 ng/ml after weight loss (P = 0.04).

Figure 1.

Losses of fat-free mass and fat mass after leptin therapy or low-calorie diet in congenital leptin-deficient (Cong leptin-def) and control subjects. Initial body weight is shown on the top of the panel. Initial fat-free masses were 67.4 ± 9.2 and 66.8 ± 8.4 kg. Initial fat masses were 56.3 ± 7.5 and 51.1 ± 10.5 kg in congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects, respectively.

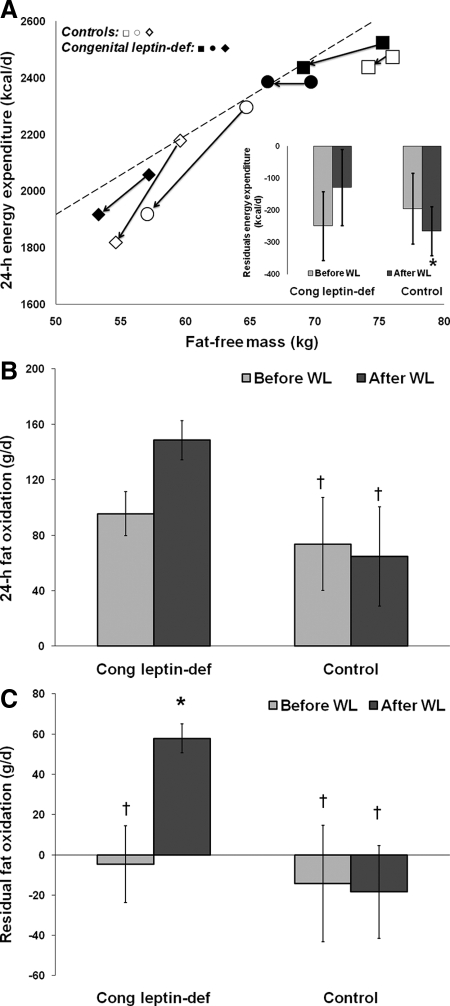

Congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects had similar unadjusted and adjusted EEs before or after weight loss (Fig. 2A). However, after weight loss and in comparison with the reference population, congenital leptin- deficient leptin-treated individuals had EEs similar to predicted values (P = 0.67), whereas controls had EEs well below predicted values (P = 0.04; Fig. 2A). Physical activity level in the chamber tended to be higher in control than in congenital leptin-deficient subjects before weight loss (1.34 ± 0.09 vs. 1.19 ± 0.06, respectively; P = 0.07). However, after weight loss, both groups had similar physical activity level (1.30 ± 0.02 vs. 1.30 ± 0.04, respectively; P = 0.80).

Figure 2.

Leptin replacement prevents the reduction in EE and enhances fat oxidation in response to weight loss. A, Twenty-four-hour EE before and after weight loss vs. fat-free mass. The regression line was calculated from the 24-h EE measured in a reference population (328 females/514 males; age, 31 ± 12 yr; weight, 90 ± 25 kg; body fat, 29 ± 11%). Squares represent males, whereas circles and rhomboids represent females. Open and closed symbols represent control and congenital leptin-deficient subjects, respectively. Inset, residuals (difference between the measured and predicted 24-h EE values) for EE before and after weight loss in congenital leptin-deficient (treated) and control individuals. B, Twenty-four-hour fat oxidation before and after weight loss. C, Residuals of 24-h fat oxidation calculated as the difference between measured and predicted fat oxidation. Values are presented as mean ± sd. *, P < 0.05 vs. reference population. †, P < 0.05 vs. congenital leptin-deficient, leptin-treated subjects. WL, Weight loss.

Whole-body 24-h fat oxidation was not different between congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects before weight loss (P = 0.89; Fig. 2B). After weight loss, however, the three congenital leptin-deficient leptin-treated individuals had greater fat oxidation compared with controls (P < 0.01; Fig. 2B). After adjusting 24-h fat oxidation for fat-free mass, energy balance, body fat content, and composition of the consumed diet, fat oxidation after weight loss was higher than predicted in the congenital leptin-deficient leptin-treated individuals (P < 0.001) and greater than in the controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 2C).

We then examined the proportion of fat mass and fat-free mass lost after body weight reduction. Fat mass loss (Fig. 1 and Table 1) represented 68% (56–84%) of total body weight loss in controls and 75% (63–80%) in congenital leptin-treated individuals, with the latter group tending to lose 1.8 kg more fat mass than controls (P = 0.12).

Discussion

We here report that congenital leptin-deficient subjects losing weight in response to leptin treatment had a metabolic rate similar to predicted value. In contrast, control obese individuals undergoing a similar weight loss by a low-calorie diet experienced the often reported “metabolic adaptation,” i.e. a decrease in metabolic rate beyond that expected on the basis of the decreases in fat-free mass and fat mass (4,5). Our results are in line with the finding that leptin administration prevented the reduction in metabolic rate in congenital leptin-deficient children (7). The absence of metabolic adaptation in congenital leptin- deficient subjects was not explained by higher physical activity level because the ratio between total EE and sleeping metabolic rate was comparable between groups.

Whether leptin itself increases metabolic rate or congenital leptin-deficient subjects respond differently to weight loss cannot be deduced from our data. Such comparison would be almost impossible because congenital leptin-deficient patients are markedly hyperphagic and would be unlikely to comply with a low-calorie diet. Furthermore, because there are only a few known cases of congenital leptin deficiency in the world, such study of caloric restriction in those subjects is not feasible. Interestingly, such study in animals suggests that leptin replacement itself increased metabolic rate (12). Indeed, ob/ob mice treated with leptin showed a faster decrease in body weight compared with pair-fed ob/ob mice. Another potential experimental paradigm would be to assess metabolic rate in obese non-leptin-deficient people losing weight in response to low-calorie diet with and without leptin administration. This experiment has not been done yet; however, individuals maintaining a reduced body weight and treated with leptin showed increased EE when compared with controls without leptin administration (6).

Importantly, we also detected a higher 24-h fat oxidation in congenital leptin-deficient, leptin-treated individuals compared with baseline fat oxidation but also in comparison to controls after weight loss. The leptin effect on fat oxidation lends support to the previous finding of increased skeletal muscle fat oxidation in response to leptin in vitro (3). A higher fat oxidation, if not compensated by increased energy and fat intake, should lead to larger fat mass loss in congenital leptin-deficient, leptin-treated vs. control individuals. Although we failed to detect a statistically significant difference in fat mass loss, congenital leptin-deficient leptin-treated individuals lost almost 2 kg more fat mass than controls. Higher fat mass loss might indeed be the consequence of the enhanced fat oxidation and the increased EE observed in congenital leptin-deficient, leptin-treated individuals. It is likely that the decrease in fat oxidation observed with weight loss in controls occurs progressively over time, which might explain why a larger difference in fat mass loss was not observed in our study. Alternatively, higher fat mass loss and fat oxidation could simply be a function of greater caloric deficit in congenital leptin-deficient vs. control subjects. Unfortunately, our study did not include measures of energy metabolism during the weight loss period itself.

An obvious weakness of our study is the small sample size that certainly impaired our ability to detect differences between congenital leptin-deficient and control subjects. The comparison with a reference population was our only choice to make proper comparisons. Finally, our data support the concept that leptin replacement enhances energy metabolism by partially preventing the reduction in metabolic rate and fat oxidation so often observed during energy restriction.

Footnotes

Funding for this work was partially from National Institutes of Health Grants RR017365 and DK063240 (to M.-L.W.), RR016996 and DK058851 (to J.L.), and an institutional grant (to E.R.). J.E.G. was supported by The International Nutrition Foundation/Ellison Medical Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 8, 2009

Abbreviation: EE, Energy expenditure.

References

- Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, Caro JF 1996 Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 334:292–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi IS, Bullmore E, Keogh J, Gillard J, O'Rahilly S, Fletcher PC 2007 Leptin regulates striatal regions and human eating behavior. Science 317:1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, Fryer LG, Müller C, Carling D, Kahn BB 2002 Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature 415:339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman LM, Heilbronn LK, Martin CK, de Jonge L, Williamson DA, Delany JP, Ravussin E 2009 Metabolic and behavioral compensations in response to caloric restriction: implications for the maintenance of weight loss. PLoS ONE 4:e4377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J 1995 Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med 332:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M, Goldsmith R, Bloomfield D, Magnano A, Weimer L, Heymsfield S, Gallagher D, Mayer L, Murphy E, Leibel RL 2005 Low-dose leptin reverses skeletal muscle, autonomic, and neuroendocrine adaptations to maintenance of reduced weight. J Clin Invest 115:3579–3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi IS, Matarese G, Lord GM, Keogh JM, Lawrence E, Agwu C, Sanna V, Jebb SA, Perna F, Fontana S, Lechler RI, DePaoli AM, O'Rahilly S 2002 Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest 110:1093–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, de Jonge L, Smith SR, Bray GA 2003 Chamber for indirect calorimetry with accurate measurement and time discrimination of metabolic plateaus of over 20 min. Med Biol Eng Comput 41:572–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge L, Nguyen T, Smith SR, Zachwieja JJ, Roy HJ, Bray GA 2001 Prediction of energy expenditure in a whole body indirect calorimeter at both low and high levels of physical activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25:929–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman ET, Toth MJ 1995 Mathematical ratios lead to spurious conclusions regarding age- and sex-related differences in resting metabolic rate. Am J Clin Nutr 61:482–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licinio J, Caglayan S, Ozata M, Yildiz BO, de Miranda PB, O'Kirwan F, Whitby R, Liang L, Cohen P, Bhasin S, Krauss RM, Veldhuis JD, Wagner AJ, DePaoli AM, McCann SM, Wong ML 2004 Phenotypic effects of leptin replacement on morbid obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypogonadism, and behavior in leptin-deficient adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4531–4536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow MJ, Min-Lee K, Brown DR, Chacko VP, Palmer D, Berkowitz DE 1999 Effect of leptin deficiency on metabolic rate in ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol 276:E443–E449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]