Abstract

In recent years the interest for natural substances in dermatotherapy and cosmetics has increased. Peat is a complex natural source of humic substances that are of potential interest in both dermatology and cosmetology. Humic substances in peat have been partially characterized and pharmacologic and biologic activities have been documented. Possible clinical applications are outlined.

Keywords: Fulvic acids, humic substances, peat

INTRODUCTION

Natural substances have historically been a rich source of lead molecules in drug development. Recently, effective high-impact technologies have become available to screen natural products.[1] There is a growing serious interest in characterization of natural substances in medicine, in particular dermatology, and dermocosmetics.[2,3]

Peat, a source of natural substances, has long been used in physiotherapy, rheumatology and sports medicine. Peat is a rich natural source of humic substances that are of potential interest in dermatology and cosmetology.

Humic substances are natural products that develop during decomposition of organic matter in humus. Humic substances are the most stable fraction of organic substances in soils. The dark color comes from quinine structures [Figure 1]. A substantial part of humic acids is in carboxylic acid functional groups that bind multivalent positively charged ions.[4] Although the composition of peat is very complex and not completely understood[5,6] the principal substances may be divided into the following categories:[7]

Figure 1.

Natural peat from the Altteicher Moor (Germany)

humic acids

humin

fulvic acids

Other major components include pectins, cellulose and lignins, wax, resins and inorganic material. Dark peat contains about 10 times more humic substances than the white garden peat. The composition and the amount of the particular ingredients may vary with the geographical area, where peat was harvested. Drying peat can cause a breakdown in the natural cellular structure that negatively interferes with its water solubility.

Humic substances are highly chemically active yet recalcitrant with respect to biodegradation. They have several biologic activities such as antibacterial, antifungal, immunomodulatory and photoprotective actions that are of potential interest in dermatology and cosmetology.

STUDIES ON THE PHARMACOLOGIC AND BIOLOGIC ACTIVITY OF PEAT

In the past, crude extracts from peat of various sources have been screened for antibacterial activity.[8] Humic acid and fulvic acid exert antimicrobial activities in vitro.[9] Antibacterial activity has been shown against a variety of pathologic germs including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae and against yeasts like Candida albicans.[9,10] Humic acids and poly(OH)carboxylates are selective inhibitors of Herpes simplex virus and Cytomegalovirus replication.[11,12] Oxihumate – a water-soluble compound of peat – inhibited HIV-1 infection of MT-2 cells with an IC(50) of 12.5 μg/ml. Treatment of free and cell-attached HIV with oxihumate irreversibly reduced infectivity, while the susceptibility of target cells to the virus was not impaired by treatment prior to infection. The infectivity of the HIV particles was inhibited by interference with CD4 binding and the V3 loop-mediated step of virus entry. No viral resistance to oxihumate developed over a 12-week period in vitro.[13] Furthermore, it was shown in vivo that oral administration of humus extract in freshwater fish prevents infection with the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida.[14] The remnants of a biodiversity of plants are responsible for the broad-range antimicrobial activity found in peat.[15,16]

Humic substances show a wide range of other activities[17] [Table 1]. A low molecular weight preparation of peat (Tolpa Torf Preparation-TTP) induces tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interferon (IFN)-α and -γ in human peripheral mononuclear blood cells in vitro.[18] Immunoprotective activity has been suggested from a study of oral treatment of athletes with TTP.[19] The effects of oxihumate on the proliferative response of lymphocytes have been studied in vitro and ex vivo. Oxihumate increased the proliferative response of phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human lymphocytes, from a concentration of 20 μg/ml and upwards. This response was even more striking in the case of lymphocytes from HIV-infected patients and similar effects were observed ex vivo following administration of a non-toxic dosage of 4 g oxihumate per day to HIV-positive individuals for two weeks. Studies revealed that stimulation of the proliferative response of lymphocytes by oxihumate is associated with an increased production of IL-2, as well as expression of the IL-2 receptor in the setting of decreased production of IL-10. Oxihumate therefore holds promise for the treatment of immunocompromised patients.[20]

Table 1.

Documented activities of humic substances[17]

| Adsorptive |

| Astringent |

| Agonistic effect on α2-adreno and dopamine (D2) receptors |

| Antiallergic |

| Antibacterial |

| Anticoagulatory |

| Anti-inflammatory |

| Antiviral |

| Chelators for heavy metals |

| Estrogenic |

| Hemostyptic |

| Hyperemic |

| UVB-protective |

Of particular interest is the UVB protection by peat substances. Humic acids were investigated in vitro using U937 culture cells. The cells were exposed to UVB and UV-induced cytotoxicity was assessed with the XTT reduction assay (EZ4U, Biozol). Ammonium humate and humic acids showed a protective activity by UVB absorption that is in the range of p-aminobenzoic acid.[21]

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis revealed that aqueous peat extracts contain up to 18 fractions of water-soluble compounds of fulvic and humic acids. These compounds have been found to have a stimulatory response on the contractile activity of smooth muscles. In vitro diffusion studies showed that the permeability of these substances across human full-thickness skin (thickness: 200 μm−1) is highly selective and the resulting stimulatory activity is dependent on the permeated fraction. Especially, the HPLC fractions 7-11 and 14 are able to permeate human skin. Fractions 7-11 show a moderate stimulatory effect on smooth muscles for more than 90 min whereas fraction 14 shows the strongest stimulatory effect which was, however, suppressed after 87 min. These results show that the cutaneous therapy with peat treatment results in transcutaneous permeation of biologically active fulvic and humic acid derivatives explaining the additional pharmacological effect of peat treatment in clinical practice.[22] In experimental rodent studies, therapeutic bathing in peat and humic acids extracted from peat resulted in significant reduction of intraabdominal gynecological adhesions.[23]

Rats treated with natural peat or isolated humic acids showed a decrease of total cholesterol, total lipids, an increase of the high-density lipoprotein fraction, and decrease in glucose levels. Furthermore, there was an increase of immunoglobulins, erythrocytes, hemoglobin, and hematocrit after 24 days of treatment.[24]

POTENTIAL INDICATIONS OF HUMIC SUBSTANCES IN DERMATOLOGY AND COSMETIC DERMATOLOGY

The use of peat has a long tradition in spa medicine and rheumatology. Whereas complete peat is mostly used under these circumstances, peat extracts and isolated humic substances are of greater interest in dermatology and cosmetology.

Because of mild astringent and anti-inflammatory activity, humic substances are useful adjuncts in the topical therapy of inflammatory skin diseases like atopic dermatitis, cheiropodopompholyx, psoriasis and mild focal hyperhidrosis.

Preparations of humic acids and other peat compounds can be specifically designed for use on the body, scalp or palmoplantar skin. The compounds allow incorporation in gels (e.g. shower gels), creams and ointments, and may be used for bath therapy as well. An open trial with daily peat application showed benefit in patients suffering from chronic hand dermatitis and psoriasis palmaris.[25] Peat from the Altteicher Moor (Germany) was used as an adjunct to standard therapy [Figure 2]. Patients reported a more rapid relief from itch, inflammation was decreased and pustule formation was stopped earlier than usual. Astringent activity of humic substances may be responsible for such an effect.[25]

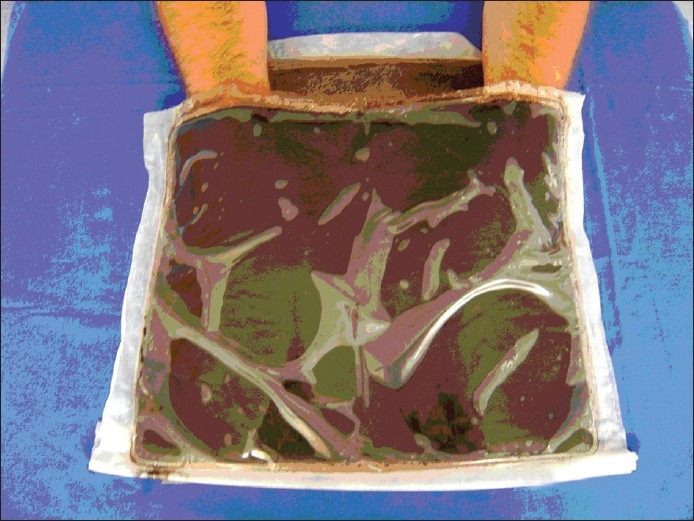

Figure 2.

Peat application in chronic hand dermatitis

The efficacy of humic substances in impetigo has not been studied. The antibacterial spectrum of in vitro activity, however, would suggest a possible role.

Another potential indication is candidal intertrigo. Both anti-yeast activity and astringent activity could favor a clinical response in this often hard-to-treat condition.

In skincare products, they are tolerated even by sensitive skin. Their UVB-protective activity might need higher concentrations than usually available in the natural peat sources.

Peat applied topically may exert systemic effects by absorption of humic substances. Water-soluble compounds of fulvic and ulmic acids have been found to have a stimulatory response on the contractile activity of smooth muscle by dopaminergic D2 and α2-adrenergic stimulation.[22] D2-receptors are involved in opioid-induced pruritus.[26] Peat baths might be beneficial in these patients, but no studies have been performed yet.

Humic substances may be of potential interest in rosacea. Here, flushing and inflammation are mediated by neurogenic mediators.[27] Serotonin uptake inhibitors and α-adrenergic agonists have been shown to suppress erythema and flushing.[28,29] Humic substances have a multimodal function in this disease, since UVB protection would inhibit a major trigger and α2-adrenergic receptor blockade might provoke a better α2-response.

Since humic acids have shown antiviral activity in vitro,[11] their use in facial masks for prevention of viral reactivation after chemical or laser peeling would be of interest [Figure 3]. Topical application in uncomplicated cases of cutaneous herpes simplex warrants clinical trials.

Figure 3.

Dermocosmetics based on natural peat

Among anti-ageing factors, plant sterols have been of particular interest for female cosmetics. Sterol extracts from peat have been marketed in facial creams. Exfoliative activity of peat is used in bath foams and shower gels. Anti-inflammatory activity is used in toothpastes and gels. The “detoxifying” activity of topical peat is a myth not substantiated by human studies.

No measurable side-effects have been observed so far.[30,31]

CONCLUSION

It is obvious that peat is a source of several chemicals which can find uses in dermatology and cosmetic dermatology. Further studies are needed to elucidate their actions and efficacy so that proper formulations can be designed for clinical use.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koehn FE. High impact technologies for natural products screening. Prog Drug Res. 2008;65:175–210. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8117-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.González S, Fernández-Lorente M, Gilaberte-Calzada Y. The latest on skin photoprotection. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:614–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reichrath J, Lehmann B, Carlberg C, Varani J, Zouboulis CC. Vitamins as hormones. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:71–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-958715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens FJ. Humus Chemistry: Genesis, Composition, Reactions. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton R, Sposito G. Molecular structure in soil substances: The new view. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:9009–15. doi: 10.1021/es050778q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson AJ, Song G, Smith E, Lam B, Novotny EH, Hayes MH. Unravelling the structural components of soil humin by use of solution-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:876–83. doi: 10.1021/es061576c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Ah SY, Woo SB, Jeong C-S, Klubachuk ON, et al. Characterization and biological activities of humic substances from mumie. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:5245–54. doi: 10.1021/jf021101e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadzhieva NZ, Tsoi EP, Turovskaia SI, Ammosova IaM. The antibacterial activity of a humic preparation made from the therapeutic peat mud of the Dzalal Abad deposit in Kirghizia. Nauchnye Doki Vyss Shkoly Biol Mauki. 1991;10:109–13. Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Rensburg CEJ, van Straten A, Dekker J. An in vitro investigation of the antimicrobial activity of oxifulvic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:853–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kneist S. Antibakterielle und antimykotische Wirkung von Huminsubstanzen aus dem Altteicher Moor. Akademie gemeinnütziger Wissenschaften zu Erfurt. Jahrbuch. 2005. pp. 65–6.

- 11.Neyts J, Snoeck R, Wutzler P, Cushman M, Klöcking R, Helbig B, et al. Poly(hydroxy)carboxylates as selective inhibitors of cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus replication. Antiviral Chem Chemother. 1992;3:215–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klöcking R, Spößig M, Wutzler P, Thiel K-D, Helbig B. Antiviral wirksame Huminsäuren und huminähnliche Polymere. Z Physiother. 1983;35:95–101. German. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Rensburg CE, Dekker J, Weis R, Smith T-L, Van Rensburg EJ, Schneider J. Investigations on the anti-HIV properties of oxihumate. Chemotherapy. 2002;48:138–43. doi: 10.1159/000064919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama Denso H, Nakagawa T. Protection against atypical Aeromonas salmonicida infection in carp (Cyprus carpio L.) by oral administration of humus extract. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69:405–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correira AF, Segovia JF, Goncalves MC, de Oliveira VL, Silveira D, Carvalho JC, et al. Amazonian plant crude extract screening for activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12:369–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basso LA, da Silva LH, Fett-Neto AG, de Azevedo WF, Jr, Moreira Ide S, Palma MS, Calixto JB, Astolfi Filho S, dos Santos RR, Soares MB, Santos DS. The use of biodiversity as source of new chemical entities against defined molecular targets for treatment of malaria, tuberculosis, and T-cell mediated diseases – a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:475–506. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000600001. Epub 2005 Nov 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klöcking R. 2 Torfsymposium Torf- und Huminstoffpräparate in der Medizin, Veterinärmedizin und Kärperpflege. Akademie gemeinnätziger Wissenschaften zu Erfurt. Jahrbuch. 2005. pp. 50–4.

- 18.Inglot AD, Zielinska-Jenczylik J, Piasecki E. Tolpa Torf Preparation (TTP) induces interferon and tumor necrosis factor production in human peripheral blood leukocytes. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1993;41:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inglot AD, Sobiech KA, Zielinska-Jenczylik J, Sypula A, Majda J, Lorenc M. Development and disappearance of tolerance to induction of interferon and tumor necrosis factor response in athletes treated with natural immunostimulant. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1999;47:237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jooné GK, Dekker J, van Rensburg CE. Investigation of the immunostimulatory properties of oxihumate. Z Naturforsch [C] 2003;58:263–7. doi: 10.1515/znc-2003-3-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kühn S, Klöcking H-P, Klöcking R. Investigations on the UV-B protective effect of humic acids, humic acid-like polymers and PABA. Akademie gemeinnütziger Wissenschaften zu Erfurt, Jahrbuch. 2005:63–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beer AM, Juninger HE, Likanov J, Sagorchev P. Evaluation of the permeation of peat substances through human skin in vitro. Int J Pharm. 2003;253:169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesrogli M, Maas DH, Mauss B, Plogmann S, Ziechmann W, Schneider J. [Successful prevention of adhesions using peat and humic acids] Zentrabl Gynä. 1991;113:583–90. German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banaszkiewicz W, Drobnik M. [The influence of natural peat and isolated humic acid solution on certain indices of metabolism and of acid-base equilibrium in experimental animals] Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 1994;45:353–60. Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollina U, Abdel-Naser MB. Pharmacotherapy of pompholyx. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1517–22. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.7.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganesh A, Maxwell LG. Pathophysiology and management of opioid-induced pruritus. Drugs. 2007;67:2323–33. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wollina U. Rhinophyma - unusual expression of simple-type keratins and S100A in sebocytes and abundance of VIP receptor positive dermal cells. Histol Histopathol. 1996;11:111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wollina U. The response of erythematous rosacea to ondasentron. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:561–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanler SD, Ondo AL. Successful treatment of the erythema and flushing of rosacea using a topically applied selective alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, oxymetazoline. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1369–71. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.11.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reichert B. Huminsäuren und ihre Derivate in der modernen Therapie. Dtsch Apotheker. 1966;18:204–6. German. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Rensburg CE, Malfield SC, Dekker J. Topical application of oxifulvic acid suppresses the cutaneous immune response in mice. Drug Dev Res. 2001;53:29–32. [Google Scholar]