Abstract

Background

Previous growth studies of Peruvian children have featured high stunting rates and limited information about body composition.

Objective

We aimed to characterize anthropometric measures of Peruvian infants 0 to 12 months of age in relation to the international growth references and biological, environmental, and socioeconomic factors.

Methods

Infants (n = 232) were followed longitudinally from birth through 12 months of age from a prenatal zinc supplementation trial conducted in Lima, Peru, between 1995 and 1997. Anthropometric measures of growth and body composition were obtained at enrollment from mothers and monthly through 1 year of age from infants. Weekly morbidity and dietary intake surveillance was carried out during the second half of infancy.

Results

The prevalence rates of stunting, underweight, and wasting did not exceed 4% based on the World Health Organization growth references. Infants of mothers from high-altitude regions had larger chest circumference (p = .006) and greater length (p = .06) by 12 months. Significant predictors of growth and body composition throughout infancy were age, sex, anthropometric measurements at birth, breastfeeding, maternal anthropometric measurements, primiparity, prevalence of diarrhea among children, and the altitude of the region of maternal origin. No associations were found for maternal education, asset ownership, or sanitation and hygiene factors.

Conclusions

Peruvian infants in this urban setting had lower rates of stunting than expected. Proximal and familial conditions influenced growth throughout infancy.

Keywords: Body composition, growth, high altitude, infants

Background

Global efforts to improve early childhood growth are motivated by its repercussions on survival, cognition, and productivity into adulthood. The potentiating effect of growth-faltering on illness and mortality is increasingly acknowledged, with 21% of deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in children under 5 years of age attributable to stunting, severe wasting, and intrauterine growth restriction [1]. Undernutrition in early childhood has been linked to compromised adult health and growth [2], delayed school entry and reduced performance on cognitive tests [3], impaired physical work capacity [4], and reduced earnings potential [5, 6].

Relative to the regions of Africa and Asia, Latin America has the lowest prevalence of underweight: less than 10% and declining [7, 8]. In 2000, a national survey in Peru reported that 7.1% of children under five were underweight, 1% were wasted, and 25.4% were stunted [9], yet disparities between urban and rural areas are marked. Earlier studies investigating growth determinants in Peruvian children demonstrated the importance of infant-feeding practices [10], consumption of animal-source foods [11], and diarrheal morbidity, in particular [12]. These studies were conducted in areas characterized by higher prevalence rates of malnutrition; less is known about the determinants of growth among infants from low-income households in urban areas where levels of malnutrition are greatly reduced. It is also true that few studies have examined maternal factors in relation to offspring growth or have investigated broader socioeconomic determinants, such as assets and wealth, which have been shown to be advantageous in other regions of the world [13, 14].

There is also a limited number of studies examining body composition during infancy relative to other populations and determining factors. Adiposity and lean-tissue mass of preschool-age children were proposed to explain the previously documented prevalence of low weight-for-height in Peruvian children relative to a North American population [15, 16]. Another study described differences in body proportions between highland and lowland Peruvian children 7 to 19 years of age [17]. The present study aimed to describe the growth and body composition of low-income Peruvian infants from birth to 12 months relative to the international reference and to other populations, and to more comprehensively evaluate the multidimensional factors determining their anthropometric outcomes.

Methods

Data collection

A subsample of infants followed through 1 year of age from a randomized, controlled trial of prenatal zinc supplementation was employed in this analysis [18–20]. The trial, conducted from 1995 through 1997 in Villa El Salvador of Lima, Peru, enrolled 1,295 women who entered prenatal care between 10 and 24 weeks of gestation and randomly assigned them to receive either zinc plus iron and folic acid or iron plus folic acid alone. Briefly, women were considered eligible if they were carrying a low-risk pregnancy (uncomplicated and eligible for vaginal delivery) with a singleton fetus and had resided in coastal Peru for 6 months or longer before becoming pregnant. Written consent to participate was obtained at enrollment and again during the early neonatal period for those participating in the follow-up study.

When the follow-up study was initiated, 642 infants were available who met the criteria of singleton birth, healthy, and residence in the study community. We selected a subsample of 232 from the enrolled population of 579 based on the availability of data at each month of follow-up. This subsample was similar to the enrolled group in terms of numbers assigned to each treatment group and across all socioeconomic characteristics except maternal education, for which there were differences between the groups in the top two levels of education completed, secondary and higher than secondary. In the regression analyses, maternal education level was not a determinant of growth outcomes.

Socioeconomic and demographic information was obtained from the mothers at enrollment, as well as clinical histories. Standard procedures were followed for obtaining anthropometric measurements from mothers at enrollment and from babies throughout infancy [21, 22]. Standing maternal height was measured with a stadiometer, and weight was recorded on a SECA scale to the nearest 100 g. Newborns were weighed at birth by hospital personnel and measured by study personnel on day 1 for crown–heel length, circumferences, and skinfold thicknesses. Thereafter, anthropometric measures of infant body size (weight, length, head circumference, calf circumference, chest circumference, and mid-upper-arm circumference [MUAC]) and body composition (triceps, calf, and subscapular skinfold measures) were taken monthly until the age of 12 months by trained personnel. The SECA scale was also used to weigh the infants to the nearest 10 g, and recumbent length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with the use of a wooden measuring board. Lange precision calipers were used to measure skinfold thicknesses.

Methods for morbidity surveillance through weekly home visits were adapted from Penny and Lanata [23–25] and carried out when the infants were 6 to 12 months of age. The fieldworkers questioned the caregivers in detail about the child’s health and examined the child if the caregiver reported any new sign of illness or worsening of existing illness or if no examination had taken place for a period of 1 month. During an examination, the respiratory rate and rectal temperature were recorded and an assessment for signs of dehydration was completed. Measures of respiratory rate were repeated if the number of counts per minute exceeded age-defined upper limits. Dietary information about infant consumption of breastmilk and complementary foods was similarly collected during the weekly morbidity surveillance by fieldworkers.

Approval for the study was granted by the Ethical Committee at the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional (IIN) and the Committee for Human Research at The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Definitions

The ponderal index (PI) was calculated as weight (kg)/length (m)3 [26, 27]. Low birthweight (LBW) was defined as less than 2,500 g. Small for gestational age (SGA) was defined as a birthweight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age [28]. Body-composition indices were calculated by the following equations: arm area (AA) = π/4*(MUAC/π)2, arm muscle area (AMA) = (MUAC − πTSF)2/4π, and arm fat area (AFA) = AA − AMA [29]. For analyses, we also summed the skinfold measures. Monthly growth velocity values were obtained by subtracting growth measures from the values for the previous month. Underweight, stunting, and wasting were defined as z-scores below −2 SD for weight-for-age, length-for-age, and weight-for-length, respectively.*

For the morbidity parameters, diarrhea was defined as three or more liquid or loose stools in the previous 24 hours. We then applied the diarrhea indicator to calculate a time-varying measure of child period prevalence of diarrhea (also referred to as longitudinal prevalence [30]) or the number of days with diarrhea divided by the number of days of observation per child. Reported fever or rectal temperature greater than 38°C qualified as fever. An ill day was defined as any day in which an infant was reported to have had cough, fever, or diarrhea. Similar to the per child prevalence of diarrhea, a time-varying child period prevalence of days ill was calculated as the number of days ill divided by the number of days of observation per child.

Additional feeding parameters were created from the dietary information collected. A child was categorized as receiving complementary foods if the mother reported consumption of solid foods (cereal, meat or fish, mixed or blended foods, stews, bread or other cereal products, and purées) plus breastmilk. When a mother reported that her infant consumed meat, fish, egg, or other milk besides breastmilk, the child was defined as having animal-source foods in his or her diet. Overall and child-specific prevalence rates for each dietary category were calculated as well as a lagged variable for each category, indicating the number of observation days on which the food was consumed divided by the number of observation days for individual children from the previous month only.

Reported employment for mothers and spouses or partners was classified as either unemployed to very low income (unemployed, temporarily employed, student, or housewife or househusband), or low to medium income (housekeeping, traveling sales, factory work, construction or manual labor, small business, service sector, military, or professional). At enrollment, each mother reported the department where she was raised. To obtain a proxy estimation of department elevations, the altitudes of the capital cities [31] were obtained from all departments and defined as “high” if they exceeded 2,500 m.

Data analysis

Growth patterns throughout infancy were observed through the use of lowess curves using linear least-squares regression with 0.8 bandwidth. A principal-components analysis was undertaken [32] to create two composite indices for household socioeconomic status/environmental status: economic viability/asset ownership and hygiene/sanitation [33]. The variables included to represent asset ownership were housing material, presence of electricity in the home, and cooking facilities; for the sanitation and hygiene dimension, the variables were toilet type, source of water, and number of persons living in the home. Bivariate analyses compared growth differences on a range of factors by applying t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson chi-squared tests of independence. Panel regression models with random effects by generalized least squares were applied to examine influences on infant growth and body-composition measures throughout infancy [33, 34]. A quadratic term for age was incorporated into modeling to quantify the decelerating rate of growth in the first year of life. The effects of prenatal zinc supplementation on growth have been reported elsewhere [35]; to adjust for these effects, a treatment group variable was included in all models. Interaction terms were created for different combinations of variables to test for multiplicative effects by the joint presence of factors. In general, statistical significance was defined as p < .05, and all data analyses were performed with the Stata software package.**

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Nearly all (96.5%) of the infants were born at term, and six newborns were classified as having low birth-weight (table 1). A large proportion (48%) of the mothers reported education beyond primary school, and approximately one-fifth had received some sort of postsecondary education. Most of the mothers (69%) did not work outside the home; approximately 10% operated small businesses. The occupations of the spouses or partners were predominantly in the low-to-medium-income category: traveling sales (22%); factory, construction, or manual labor (32%); small businesses (14%); or the service sector (10%). Eleven of the 24 departments had high-altitude (> 2,500 m) regions; 34.2% of mothers originated from one of these departments. More than two-thirds (68%) of the mothers who were from a high-altitude department came from an urban area.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of Peruvian infants and their mothers

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD or proportion (n = 232) |

|---|---|

| Infant | |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 49.1 |

| Male | 50.9 |

| Pregnancy outcome | |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | 39.6 ±1.7 |

| Preterm (%) | 3.5 |

| Low birthweight (%) | 3.0 |

| Maternal | |

| Age (yr) | 24.9 ± 5.3 |

| Education (%) | |

| < Primary | 12.1 |

| Primary | 40.1 |

| Secondary | 28.0 |

| > Secondary | 19.8 |

| Primiparous (%) | 44.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.3 |

| Maternal height (cm) | 151.3 ± 5.00 |

| Single (%) | 14.7 |

| Household | |

| Housing material (%) | |

| Carton | 26.7 |

| Wood | 15.1 |

| Brick | 57.8 |

| Toilet (%) | |

| Open air | 9.1 |

| Latrine and other | 31.4 |

| Toilet | 59.5 |

| Electricity in home (%) | 79.3 |

| Maternal income (%) | |

| Unemployed to very low income | 80.6 |

| Low to medium income | 19.4 |

| Income of spouse or partner (%) | |

| Unemployed to very low income | 6.7 |

| Low to medium income | 93.3 |

Growth patterns of infants

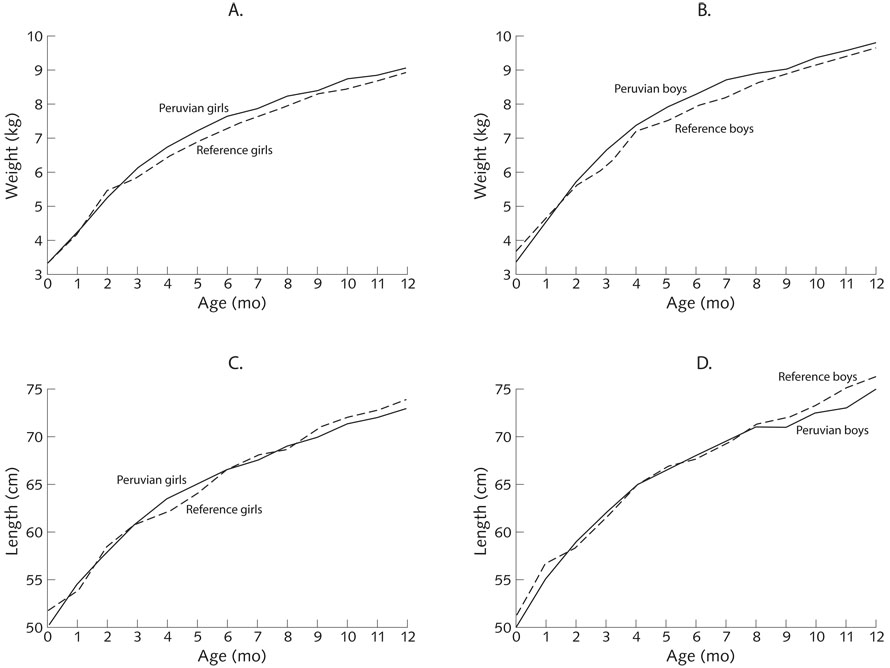

All growth trajectories had steeper ascending slopes in the first half of infancy, followed by decelerating rates or plateauing of growth in the second half. The mean z-scores were 0.17 ± 0.90 SD for weight-for-age, 0.07 ± 1.02 SD for length-for-age, and 0.18 ± 1.00 SD for weight-for-length. Through infancy, the z-scores for all three anthropometric indicators were close to zero (fig. 1). Only in month 6 did the infants have a negative z-score, which was −0.02 ± 1.02 SD for length-for-age. The percentages of infants classified as undernourished at 6 and 12 months, respectively, were 1.7% (4/232) and 2.2% (5/232) stunted, 2.6% (6/232) and 3.5% (8/232) underweight, and 1.3% (3/232) and 1.3% (3/232) wasted.

FIG. 1.

Anthropometric measures for infants 0 to 12 months of age. Solid lines indicate values for Peruvian infants and broken lines indicate reference values.* (A) Weight for girls; (B) weight for boys; (C) length for girls; (D) length for boys

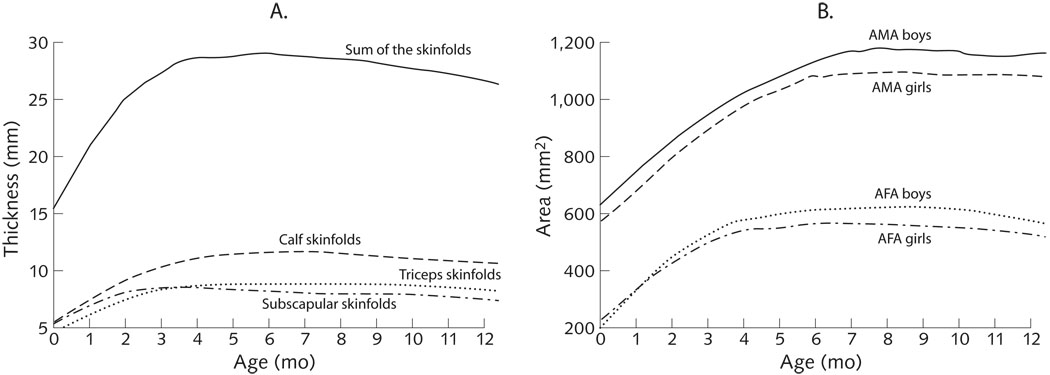

Skinfold measurements increased rapidly in the first few months of life, followed by a slight but consistent decline beginning in month 4 for subscapular skinfolds, and eventually in month 7 for both triceps and calf skinfolds. The observed decline in adipose tissue during the latter part of infancy was more readily apparent in the sum of skinfolds indicator (fig. 2A). Following a similar pattern, arm fat area peaked around month 6, followed by declines, while arm muscle area rose more steadily until month 7 or 8, in recognition of sex differences, as noted above (fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Body composition measures of Peruvian infants 0 to 12 months of age. (A) Skinfold thicknesses; (B) arm muscle area (AMA) and arm fat area (AFA)

Differences between boys and girls in anthropometric measures became significant only after the neonatal period, except for head circumference, which was 34.5 ± 1.4 cm in boys and 34.1 ± 1.3 cm in girls at birth (p < .05). Skinfold measures did not differ consistently according to sex throughout infancy. Girls were born with greater arm fat area than boys on average, but boys surpassed girls in arm fat area during months 3 through 9 and month 12 (p < .05). Arm muscle area was also significantly greater in boys than in girls after month 1 and continuing through 12 months of age. The correlation coefficients between infant anthropometric measures at 12 months and birth measures were greater for head circumference (R = 0.47), length (R = 0.39), and weight (R = 0.38) than for chest circumference (R = 0.32), calf circumference (R = 0.31), MUAC (R = 0.26), and skinfold measures (R < 0.27).

Factors influencing growth

Multiple factors were investigated in longitudinal models to determine their influence on variation in the growth outcomes of the infants (table 2). In all models, infant age and corresponding birth anthropometric measures significantly affected growth outcomes (p < .01). A negative coefficient for the age quadratic term for all anthropometric outcomes had a decelerating rate of growth with increasing age. Sex was a significant covariate in determining all measures, except calf circumference.

TABLE 2.

Longitudinal regression models for growth and body composition of Peruvian infants

| Covariates: coefficient ± SEa | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth outcome | Age (mo) | Age (quadratic) |

Female sex | Birth measurementb |

Maternal measurementc |

Primiparity | Diarrhea | Breastmilk in diet |

Maternal high-altitude origin |

Overall R2 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.97 ± 0.00 | −0.04 ± 0.00 | −0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | — | — | 0.02 ± 0.01 | — | 0.81 |

| Length (cm) | 3.02 ± 0.01 | −0.11 ± 0.00 | −0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.23 | — | — | 0.62 ± 0.24 | 0.91 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 1.56 ± 0.00 | −0.06 ± 0.00 | −0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | ND | 0.39 ± 0.14 | — | — | — | 0.86 |

| Chest circumference (cm) | 1.15 ± 0.06 | −0.03 ± 0.00 | −1.33 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.07 | ND | — | 0.43 ± 0.14 | — | 0.72 ± 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Calf circumference (cm) | 1.47 ± 0.01 | −0.08 ± 0.00 | — | 0.38 ± 0.08 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.73 |

| MUAC (cm) | 0.89 ± 0.00 | −0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | — | — | — | 0.02 ± 0.01 | — | 0.50 |

| Sum of skinfolds (triceps + calf + subscapular) (mm) |

2.46 ± 0.00 | −0.17 ± 0.00 | −1.77 ± 0.25 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | — | — | 0.12 ± 0.04 | — | 0.26 |

MUAC, mid-upper-arm circumference; ND, measurement was not taken on the mother; —, not significant in the mother

All models were adjusted for zinc treatment.

The birth measurement that corresponds to the outcome measurement (e.g., birthweight for weight; birth calf circumference for calf circumference).

The maternal measurement at enrollment that corresponds to the outcome measurement.

Between 6 and 12 months of age, infants were reported to have been breastfed on 92% of the days of observation, received complementary foods on 78% of days, and received animal-source foods on 66% of days. None of the infant-feeding parameters were significant in longitudinal modeling except the presence of breastmilk in the diet at the time of the anthropometric measure, which was positively associated with weight, MUAC, and sum of skinfold measures. The infants were ill for a median of 36.4% days of observation but had diarrhea on 5.3% of days. Child period prevalence of diarrhea showed a trend toward reducing all growth outcomes, but the relationship was statistically significant for chest circumference alone, where a positive effect on growth was observed.

Several maternal characteristics influenced growth in these infants. Primiparity had a positive effect on change in length and head circumference after adjustment for other variables. For weight, length, head circumference, and sum of skinfolds, a positive influence was found with the corresponding value in the mother at 10 to 24 weeks of gestation. After adjustment for covariates, a maternal history of living in a region of high altitude was associated with increased linear growth (p = .01) and larger chest circumference (p = .008) longitudinally throughout infancy. However, neither maternal education, asset ownership, nor the sanitation and hygiene indices retained significance in longitudinal modeling after adjustment for covariates. Finally, no evidence for effect modification was found across the covariates.

Discussion

In this longitudinal analysis, we studied patterns of anthropometric change in Peruvian infants from birth to 12 months in relation to a range of environmental and biological factors. Proximal biological factors, including infant age and sex, corresponding birth measurements, and breastfeeding, affected longitudinal growth outcomes in the infants. In contrast with a previous analysis [35], the longitudinal prevalence of diarrhea had little effect on growth outcomes; the difference in results may be due to differing maternal education levels in the two samples. Other morbidities, such as fever and mild respiratory illness, also did not affect growth. Maternal anthropometric measurements were positively associated with the corresponding markers of weight, length, and sum of skinfolds in the infant, a result consistent with other recent findings relating maternal body size and composition with that of neonates [36, 37] and infants [38]. Interestingly, we also found that infants of mothers with high-altitude ancestry had greater length and chest circumference, especially toward the end of infancy. Traditional variables known to affect nutritional status in resource-poor settings—maternal education, economic factors, hygiene and sanitation conditions, and the presence of animal-source foods in the child’s diet—were not found to significantly influence growth in these infants. The urban setting may have afforded certain advantages, such as access to education, foodstuffs, and health care, which may have reduced or removed these effects.

The prevalence of undernutrition in these infants was notably lower than the rates observed among children in other developing countries [1]. Stunting prevalence, in particular, was lower than expected in these infants (< 4%) on the basis of prevalence rates previously reported in Peru [15, 16]. Although different growth standards were used, the Demographic and Health Survey 2000 in Peru reported that 26.7% of children under 1 year of age were stunted [39]. The infants in our study may have had a growth advantage afforded to them by the iron and folic acid taken by the mothers in both prenatal supplementation groups [40] or potentially from the additional health care provided in association with the trial. Both factors represent limitations in generalizing the findings to the wider population of Peruvian infants, although iron and folic acid supplements are the standard protocol for prenatal care in Peru. It should be noted that the prevalence of stunting in these infants increased toward the end of infancy and may have reached levels comparable to those in other studies in the second and third years of life. In this analysis, the effects on infants of prenatal supplementation of mothers with zinc were controlled for in longitudinal modeling. However, findings from the analysis of the treatment effect showed that infants whose mothers were prenatally supplemented with zinc had greater weight, calf circumference, chest circumference, and calf muscle area [35], which could have influenced the overall growth trajectories presented here.

Few studies in Peru have investigated longitudinal changes in several different measures of body composition, as was done in our study. In one study, skinfold thicknesses of Peruvian infants aged 6 to 60 months were found to be lower, arm muscle areas similar, and total body water relative to weight higher than National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reference values [15, 16]. The investigators suggested that greater lean tissue was responsible for the higher weight-for-height values in the children. Although our study found slightly higher markers of adiposity (triceps, subscapular skinfold thickness, arm fat area) at 6 months, the differences diminished by 12 months, reinforcing an interpretation that adequate weight and weight-for-length measurements may in part reflect muscle tissue accretion. Other studies have suggested that larger abdominal circumferences in populations of Latin America could account for the low prevalence of weight-for-height deficits [41], but we did not investigate this measure.

Larger chest circumference and greater linear growth were found in the infants of mothers originating from high-elevation regions. There are limitations to our interpretation of this interesting finding, since we lacked information on the precise periods of residence in high-altitude regions by the mothers and had no paternal data. The capital city elevation data extrapolated for the regions, however, were probably sufficient, since the majority of mothers reported coming from urban areas in these departments. Collective evidence for genetic adaptation to living at high altitudes or chronic hypoxia over several generations is available [42]. The hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway, which regulates several hypoxia-responsive genes, has been implicated as one of the mechanisms driving these genetic adaptations [43]. We observed that the effect of high-altitude ancestry on infant linear growth was independent of maternal height in longitudinal modeling, a result suggesting separate genetic or gene–environment mechanisms. Increases in chest circumference may be due to improvements in lung volume or, more proximally, pulmonary function. Chest morphology (greater chest depth) and forced vital capacity and expiratory volume were improved in adulthood with ancestral and early developmental exposure to high altitude [44]. The relevance of these findings may be better understood with further investigation of even longer-term health implications for infants with some degree of high-altitude ancestry living in coastal (low-altitude) Peru.

In summary, this study demonstrated growth patterns similar to those reported internationally in the World Health Organization (WHO) Growth Standards* with relatively low rates of stunting, undernutrition, and wasting in this urban-based, low-income population. It highlights again the importance of breastmilk in the diet as well as familial, potentially genetic factors related to maternal anthropometric features and high-altitude ancestry.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by cooperative agreements with the US Agency for International Development/Office of Nutrition (USAID/OHA) and Johns Hopkins University (DAN-5116-A-00-8-51-00 and HRN-A-00-97-00015-00) and a National Institutes of Health International Maternal and Child Health Training Grant (T32HD046405-01A). Preparation of the manuscript was also supported by NICHD HD 42675.

We would like to express our appreciation to all the mothers and infants who agreed to participate in this study; the health personnel from Centro Materno Infantil Cesar López Silva and the health authorities from the Ministry of Health, DISA Lima Sur, for their collaboration; and the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional team for their commitment and hard work during the implementation of this study.

Footnotes

WHO Anthro 2005, Beta version Feb 17, 2006: Software for assessing growth and development of the world’s children. 2006. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Stata Statistical Software. 8.0(8.2). 2005. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp.

References

- 1.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J and the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371:340–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendez MA, Adair LS. Severity and timing of stunting in the first two years of life affect performance on cognitive tests in late childhood. J Nutr. 1999;129:1555–1562. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.8.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas JD, Murdoch S, Rivera J, Martorell R. Early nutrition and later physical work capacity. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S41–S48. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norgan NG. Long-term physiological and economic consequences of growth retardation in children and adolescents. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:245–256. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoddinott J, Maluccio JA, Behrman JR, Flores R, Martorell R. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet. 2008;371:411–416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNICEF. Progress for children: A report card on nutrition. Vol. 4. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2006. p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrimpton R, Victora CG, de Onis M, Lima RC, Blossner M, Clugston G. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: Implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E75. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lima. 2001. Instituto Nacional Estadistica e Informatica, Measure/DHS+ Macro International, USAID, and UNICEF. República de Perú: encuesta demográfica y de salud familiar 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piwoz EG, Creed de Kanashiro H, Lopez de Romana GL, Black RE, Brown KH. Feeding practices and growth among low-income Peruvian infants: a comparison of internationally-recommended definitions. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:103–114. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marquis GS, Habicht JP, Lanata CF, Black RE, Rasmussen KM. Breast milk or animal-product foods improve linear growth of Peruvian toddlers consuming marginal diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Checkley W, Epstein LD, Gilman RH, Cabrera L, Black RE. Effects of acute diarrhea on linear growth in Peruvian children. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:166–175. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong R, Mishra V. Effect of wealth inequality on chronic under-nutrition in Cambodian children. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wamani H, Tylleskar T, Astrom AN, Tumwine JK, Peterson S. Mothers’ education but not fathers’ education, household assets or land ownership is the best predictor of child health inequalities in rural Uganda. Int J Equity Health. 2004;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trowbridge FL, Marks JS, Lopez de Romana G, Madrid S, Boutton TW, Klein PD. Body composition of Peruvian children with short stature and high weight-for-height. II. Implications for the interpretation for weight-for-height as an indicator of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:411–418. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutton TW, Trowbridge FL, Nelson MM, Wills CA, Smith EO, Lopez de Romana G, Madrid S, Marks JS, Klein PD. Body composition of Peruvian children with short stature and high weight-for-height. I. Total body-water measurements and their prediction from anthropometric values. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:513–525. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stinson S, Frisancho AR. Body proportions of highland and lowland Peruvian Quechua children. Hum Biol. 1978;50:57–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zavaleta N, Caulfield LE, Garcia T. Changes in iron status during pregnancy in Peruvian women receiving prenatal iron and folic acid supplements with or without zinc. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:956–961. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.4.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caulfield LE, Zavaleta N, Figueroa A. Adding zinc to prenatal iron and folate supplements improves maternal and neonatal zinc status in a Peruvian population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1257–1263. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien KO, Zavaleta N, Caulfield LE, Wen J, Abrams SA. Prenatal iron supplements impair zinc absorption in pregnant Peruvian women. J Nutr. 2000;130:2251–2255. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.9.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, Ill, USA: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson RS. Principles of nutritional assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penny ME, Peerson JM, Marin RM, Lanata CF, Lonnerdal B, Black RE, Brown KH. Randomized, community-based trial of the effect of zinc supplementation, with and without other micronutrients, on the duration of persistent childhood diarrhea in Lima, Peru. J Pediatr. 1999;135:208–217. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penny ME, Marin RM, Duran A, Peerson JM, Lanata CF, Lonnerdal B, Black RE, Brown KH. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of daily supplementation with zinc or multiple micronutrients on the morbidity, growth, and micronutrient status of young Peruvian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:457–465. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanata CF, Quintanilla N, Verastegui HA. Validity of a respiratory questionnaire to identify pneumonia in children in Lima, Peru. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:827–834. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.4.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohrer F. Index of state of nutrition. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1921;68:580. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landmann E, Reiss I, Misselwitz B, Gortner L. Ponderal index for discrimination between symmetric and asymmetric growth restriction: Percentiles for neonates from 30 weeks to 43 weeks of gestation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:157–160. doi: 10.1080/14767050600624786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frisancho AR. New norms of upper limb fat and muscle areas for assessment of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:2540–2545. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.11.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris SS, Cousens SN, Kirkwood BR, Arthur P, Ross DA. Is prevalence of diarrhea a better predictor of subsequent mortality and weight gain than diarrhea incidence? Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:582–588. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welcome to the Weather Underground. [Accessed 9 June 2009];Weather Underground 2007. Available at: http://www.wunderground.com/

- 32.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton L. Statistics with STATA. Belmont, Calif, USA: Brooks/Cole; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iannotti LL, Zavaleta N, Leon Z, Shankar AH, Caulfield LE. Maternal zinc supplementation and growth in Peruvian infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:154–160. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leary S, Fall C, Osmond C, Lovel H, Campbell D, Erikkson J, Forrester T, Godfrey K, Hill J, Jie M, Law C, Newby R, Robinson S, Yajnik C. Geographical variation in relationships between parental body size and offspring phenotype at birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1066–1079. doi: 10.1080/00016340600697306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hull HR, Dinger MK, Knehans AW, Thompson DM, Fields DA. Impact of maternal body mass index on neonate birthweight and body composition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:416.e1–416.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demerath EW, Choh AC, Czerwinski SA, Lee M, Sun SS, Chumlea WC, Durren D, Sherwood RJ, Blanjero J, Towne B, Siervogel RM. Genetic and environmental influences on infant weight and weight change: The Fels Longitudinal Study. Am J Hum Biol. 2007;19:692–702. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lima, Peru: INEI/UNICEF; Instituto Nacional Estadistica e Informatica (INEI), DHS/Macro International Encuesta demografica y de salud familiar 2000; p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramakrishnan U, Neufeld LM, Flores R, Rivera J, Martorell R. Multiple micronutrient supplementation during early childhood increases child size at 2 y of age only among high compliers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1125–1131. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Post CL, Victora CG. The low prevalence of weight-for-height deficits in Brazilian children is related to body proportions. J Nutr. 2001;131:1290–1296. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore LG. Human genetic adaptation to high altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 2001;2:257–279. doi: 10.1089/152702901750265341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore LG, Shriver M, Bemis L, Hickler B, Wilson M, Britsaert T, Parra E, Vargas E. Maternal adaptation to high-altitude pregnancy: An experiment of nature—a review. Placenta. 2004;25 suppl A:S60–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brutsaert TD, Soria R, Caceres E, Spielvogel H, Haas JD. Effect of developmental and ancestral high altitude exposure on chest morphology and pulmonary function in Andean and European/North American natives. Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11:383–389. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1999)11:3<383::AID-AJHB9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]