Palladium-Catalyzed Arylation and Alkylation

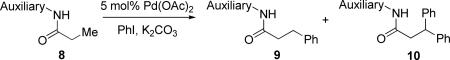

We have developed a method for auxiliary-directed, palladium-catalyzed β-arylation and alkylation of sp3 and sp2 C-H bonds in carboxylic acid derivatives. The method employs a carboxylic acid 2-methylthioaniline- or 8-aminoquinoline amide substrate, aryl or alkyl iodide coupling partner, palladium acetate catalyst, and an inorganic base. By employing 2-methylthioaniline auxiliary, selective monoarylation of primary sp3 C-H bonds can be achieved. If arylation of secondary sp3 C-H bonds is desired, 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary may be used. For alkylation of sp3 and sp2 C-H bonds, 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary affords the best results. Some functional group tolerance is observed and amino- and hydroxyacid derivatives can be functionalized. Preliminary mechanistic studies have been performed. A palladacycle intermediate has been isolated, characterized by X-ray crystallography, and its reactions have been studied.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, transition-metal-catalyzed functionalization of carbon-hydrogen bonds has emerged as an efficient method for carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formation.1 Most of the developed methodology centers on the functionalization of sp2 C-H bonds. Electron-rich heterocycles can be predictably and regioselectively arylated under palladium, rhodium, iridium, copper, and nickel catalysis.2 Functionalization of directing-group-containing arenes has been extensively investigated. Palladium- and ruthenium-catalyzed arylation of imines, anilides, 2-arylpyridine derivatives, benzamides, benzoic acids, and nitroarenes has been demonstrated allowing short syntheses of the corresponding biaryls.3 These arylations are highly ortho-selective; however, in some cases, meta selectivity has been achieved.4

For both kinetic and thermodynamic reasons, metal-catalyzed functionalization of unactivated sp3 C-H bonds is more difficult than that of sp2 hybridized carbon-hydrogen bonds. The activation of sp2 C-H bonds is favored by precoordination of the arene π system to the transition metal as well as the subsequent formation of aryl-metal bond that is typically stronger than the corresponding alkyl-metal bond.5 In contrast, benzylic or α to heteroatom sp3 carbon-hydrogen bonds undergo functionalization relatively easily, presumably due to weakness of those C-H bonds and proximity of aromatic system or electron lone pair. Consequently, transition-metal-catalyzed functionalization of activated sp3 C-H bonds is quite common and many examples have been recently described in literature.6 On the other hand, catalytic functionalization of non-activated, alkane sp3 C-H bonds is rare. Most of the examples published so far report functionalization of sp3 C-H bonds adjacent to quarternary centers which is the easiest case due to entropic considerations and impossibility of β-hydride elimination from the metalated intermediates.7 Notable exceptions include Ohno's synthesis of indoline derivatives from N-protected 2-bromoanilines, Yu's 2-substituted pyridine alkylation, and β-arylation of carboxylic acid pentafluoroanilides.8

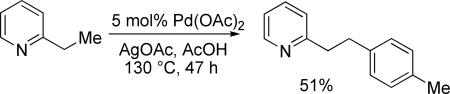

We reported in 2005 that 2-substituted pyridines are arylated by employing a combination of palladium acetate catalyst, stoichiometric silver acetate, and aryl iodide coupling partner.9a While most examples involve arylation of sp2 C-H bonds, p-tolylation of 2-ethylpyridine was also demonstrated in moderate yield (eq 1). Unfortunately, 2-ethylpyridine was the only substrate that underwent clean arylation of unactivated sp3 C-H bonds. Other substrates afforded either a mixture of mono- and polyarylation products or stilbene derivatives that can arise from β-hydride elimination from palladated intermediates.

|

(1) |

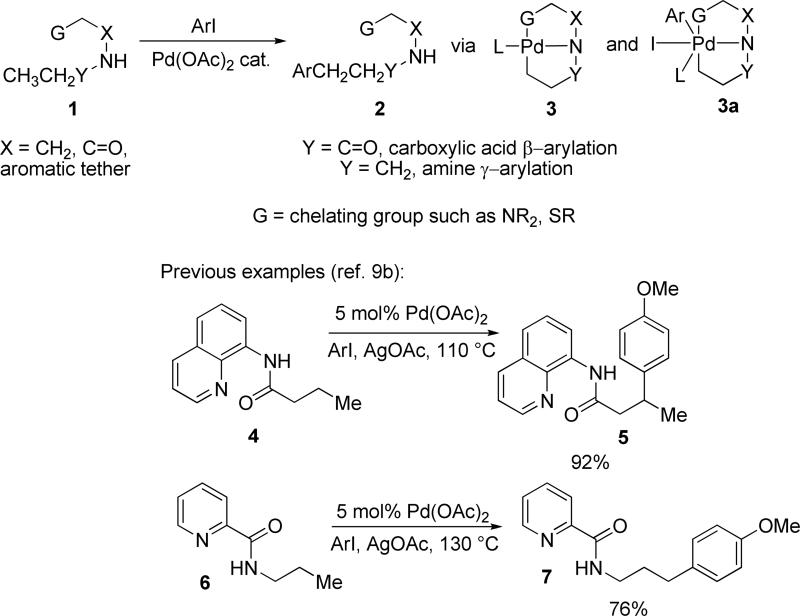

We reasoned that the generality of the method could be improved by using pyridine or other chelating group as a removable auxiliary (Scheme 1). The reaction mechanism most likely involves cyclopalladation to afford 3 and step where Pd(II) is converted to a high-energy Pd(IV) species 3a (Scheme 1). An additional chelating group should stabilize Pd(IV) species and facilitate the cyclometalation step. Additionally, β-hydride elimination should be retarded by saturating the coordination sites on palladium. Depending on the attachment of the auxiliary, either β-arylation of carboxylic acids or γ-arylation of amines could be achieved. After the arylation, auxiliary could be removed by hydrolysis. We successfully demonstrated the concept and a preliminary account has been published.9b Corey has used this methodology to arylate protected α-amino acid derivatives.10a Chen has employed the arylation in context of celogentin total synthesis, demonstrating that C-H activation methodology is compatible with complex molecular environment.10b Pyridine and quinoline auxiliary directed acetoxylation of sp2 C-H bonds has been recently reported.11

Scheme 1.

Auxiliaries for sp3 C-H Bond Arylation

We report here a method for auxiliary-directed, palladium-catalyzed arylation and alkylation of unactivated sp3 C-H bonds. Alkylation of sp2 C-H bonds is also demonstrated. Arylation of sp2 C-H bonds was not investigated since benzylamines and simple N-isopropyl benzamides can be arylated without the requirement of an auxiliary.12 Mechanistic studies are also described.

2. Results

2.1. Auxiliary Optimization Studies

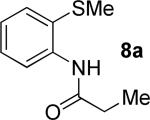

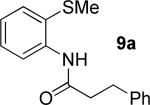

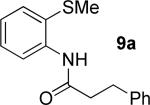

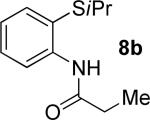

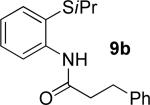

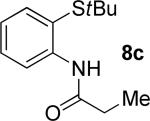

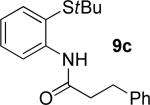

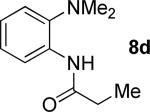

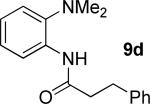

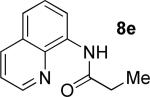

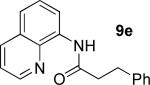

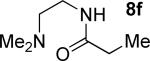

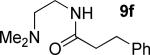

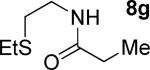

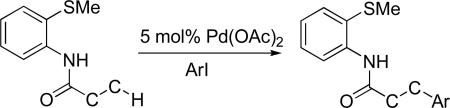

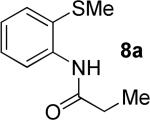

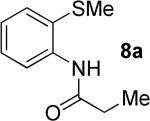

A successful auxiliary requires a nitrogen or sulfur coordinating group and a comparatively acidic NH group.13 The initial optimization experiments were directed towards using stoichiometric additives other than AgOAc to promote arylation. For the arylation of 8a, a combination of inorganic base and a hydroxylic solvent was discovered to be successful.14 Subsequently, propionamides of a number of readily available auxiliaries were subjected to the optimized arylation conditions (Table 1). The conditions for the arylation involve heating substrate with iodobenzene in tert-amyl alcohol/water mixture in the presence of K2CO3 or K3PO4 base at 90-110 °C. 2-Methylthio-N-propionylaniline was efficiently arylated at 90 °C affording the monoarylation product predominately (entries 1 and 2). Better selectivity for the monophenylation was observed in mixed water/alcohol solvent. Increase of the coordinating group size from thiomethyl to thioisopropyl resulted in slight lowering of yield (entry 3). t-Butyl derivative 8c was shown to be inefficient and less than 20% conversion to the product was observed (entry 4). 2-Dimethylamino-N-propionylaniline propionate 8d was phenylated affording a reasonable conversion to the products. Use of the previously reported 8-aminoquinoline derivative resulted in formation of mono/diarylation product mixture (entry 6). Aliphatic auxiliaries such as 2-ethylthioethylamine and 2-dimethylaminoethylamine are not effective and the corresponding propionamides were arylated with low conversions (entries 7 and 8).

Table 1.

Auxiliary Optimization Studiesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | amide | solvent, T | major product | NMR yield, % |

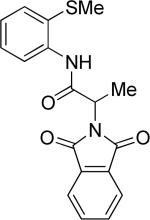

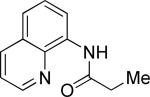

| 1 |

|

t-Amyl-OH, 90 °C |

|

55% 9a 22% 10a |

| 2 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 90 °C |

|

84% 9a 13% 10a |

| 3 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 90 °C |

|

59% 9b 8% 10b |

| 4 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 90 °C |

|

19% 9c |

| 5 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 110 °C |

|

61% 9d 6% 10d |

| 6 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 110 °C |

|

66% 9e 17% 10e |

| 7b |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 90 °C |

|

45% 9f |

| 8 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 4/1, 90 °C |

|

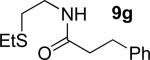

10% 9g |

Amide (1 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 equiv), base (2.5 equiv), and PhI (3 equiv). Yields are NMR yields against dichloroethane internal standard. See the Supporting Information for details.

Base used - K3PO4.

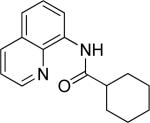

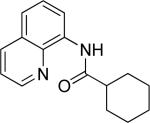

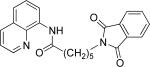

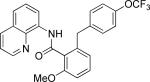

2.2. Arylation of Primary C-H Bonds – 2-Methylthioaniline Auxiliary

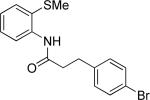

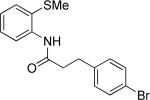

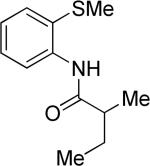

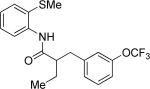

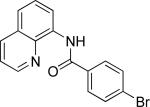

The optimization results show that the arylations are successful if commercially available 2-methylthioaniline and 8-aminoquinoline auxiliaries are employed (Table 1). Furthermore, 2-isopropylthioaniline and 2-dimethylaminoaniline auxiliaries are also efficient; however, these compounds are not commercially available. 2-Methylthioaniline auxiliary affords the best selectivity for monoarylation of primary carbon-hydrogen bonds (entry 2 vs. entry 6, Table 1). Arylation scope by employing 2-methylthioaniline auxiliary is shown in Table 2. The arylation of propionyl derivative 8a with p-bromoiodobenzene is successful in t-amyl alcohol/water mixture by employing K2CO3 base. Monoarylation product was obtained in 60% yield accompanied with 9% of diarylated species (entry 1). Reaction in acetonitrile is somewhat slower and afforded clean monoarylation (entry 2). 2-Methylbutyric acid amide was selectively arylated at β-position and the product was isolated in 60% yield (entry 3). Some functionality is tolerated on the amide.15

Table 2.

Arylation of Primary C-H Bondsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | amide | solvent, T, base | major product | yield, % |

| 1b |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 90 °C, K2CO3 |

|

60 |

| 2 |

|

CH3CN 90 °C, K2CO3 |

|

54 |

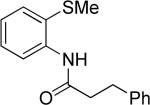

| 3 |

|

t-Amyl-OH/H2O 90 °C, K2CO3 |

|

60 |

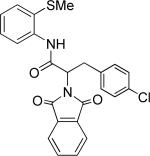

| 4 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, K2CO3 |

|

65 |

| 5 |

|

Toluene 110 °C, CsOAc |

|

79 |

| 6 |

|

Toluene 110 °C, CsOAc |

|

60 |

| 7 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, K2CO3 20 mol% PivOH |

|

47 |

Amide (1 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 equiv), base (2.5 equiv), and ArI (3-4 equiv) Yields are isolated yields. See the Supporting Information for details.

Diarylated product also isolated (9%). In all other cases, <5% diarylation was observed.

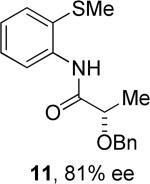

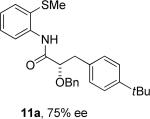

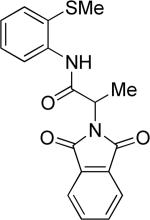

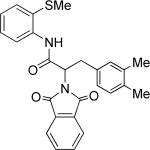

Thus, benzyl protected lactic acid derivative 11 was arylated with 4-iodo-t-butylbenzene affording the product 11a in 65% yield (entry 4). If 11 with 81% ee was employed in arylation, partial racemization was observed and 11a was obtained with 75% ee. Phthaloyl protected alanine amide can be arylated by electron-rich 3,4-dimethyliodobenzene (entry 5) and electron-poor 4-chloroiodobenzene (entry 6). In this case, highest conversion was obtained if toluene solvent and cesium acetate base were employed. Corey has reported arylation of phthaloyl-protected amino acids by employing 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary, palladium acetate catalyst, and stoichiometric silver acetate.10a However, clean β-monoarylation of methyl groups was elusive.

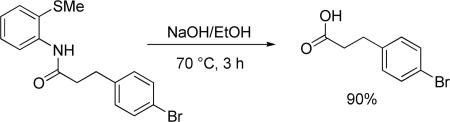

We also showed that directing group can be removed under base hydrolysis affording a phenylpropionic acid derivative (eq 2). Thus, p-bromophenylpropionic acid 2-methylthioanilide was heated with NaOH in ethanol to afford 90% of the hydrolysis product.

|

(2) |

Secondary C-H bond arylation proceeds with a moderate yield even for a weak benzylic bond (entry 7) and requires the presence of catalytic pivalic acid additive employed by Larock and Fagnou.16 It has been suggested that pivalate anion acts as a catalytic proton shuttle between the substrate and inorganic base.16a To efficiently arylate methylene groups one needs to employ another auxiliary as shown below.

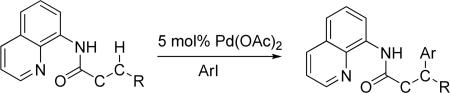

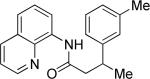

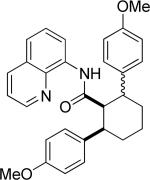

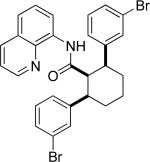

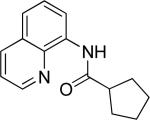

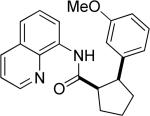

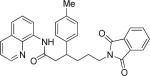

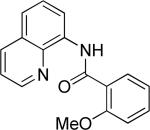

2.3. Arylation of Secondary C-H Bonds – 8-Aminoquinoline Auxiliary

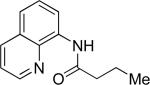

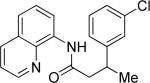

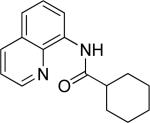

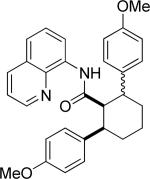

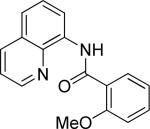

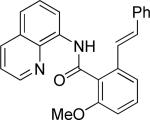

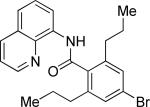

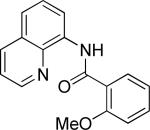

Efficient arylation of secondary C-H bonds is possible by employing 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary. Optimal conditions involve heating substrate with aryl iodide and Cs3PO4 base in t-amyl alcohol solvent. The arylation is highly selective for the β-position of the alkyl chain. Butyric acid derivative is arylated in good yield with both electron-rich and electron-poor aryl iodides (Table 3, entries 1 and 2). Cyclohexanecarboxylic acid amide can be arylated by p-methoxyiodobenzene and 3-bromoiodobenzene affording diarylation products in reasonable yields. The diastereoselectivity depends on the aryl iodide. p-Methoxyphenylation affords about 4/1 isomer ratio (entry 3) or about 5/1 ratio if previously reported conditions9b that use AgOAc are employed with all-cis isomer predominating in both cases. m-Bromophenylation results in the formation of all-cis isomer (entry 5). m-Methoxyphenylation of cyclopentanecarboxylic acid derivative affords monoarylation product cis isomer (entry 6). ω-Phthaloyl-protected amino group is compatible with the arylation conditions as shown in entry 7. 6-Aminohexanoic acid derivative is p-tolylated in good yield. Finally, alkenylation of sp2 C-H bonds was shown to be successful (entry 8). 2-Methoxybenzoic acid amide was reacted with iodostyrene affording the product in good yield if AgOAc halide removing agent was employed.

Table 3.

Arylation of Secondary C-H Bondsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | amide | solvent, T, base | major product | yield, % |

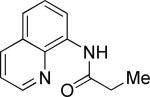

| 1 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, Cs3PO4 |

|

79 |

| 2 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, Cs3PO4 |

|

81 |

| 3 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, CS3PO4 |

|

63 all-cis 16 cis-trans |

| 4 |

|

Neat 90 °C, AgOAc |

|

69 all-cis 13 cis-trans |

| 5 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, Cs3PO4 |

|

52 all-cis only |

| 6 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 110 °C, Cs3PO4 |

|

52 |

| 7 |

|

t-Amyl-OH 90 °C, Cs3PO4 |

|

76 |

| 8 |

|

Neat 90 °C, AgOAc |

|

64 |

Amide (1 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 equiv), base (1.5-3.3equiv), and ArI (2-4 equiv) Yields are isolated yields. See the Supporting Information for details.

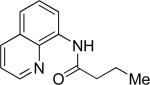

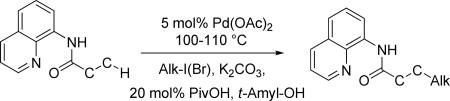

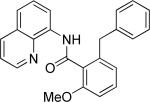

2.4. Alkylation of C-H Bonds

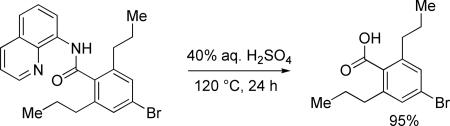

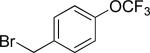

The previously described conditions that involve use of AgOAc for iodide removal were not successful for C-H bond alkylation. Silver acetate reaction with alkyl iodides competes with the C-alkylation resulting in low catalytic turnover. The new conditions should be successful since the competitive destruction of alkyl iodides is expected to be slower. It was determined that the optimal auxiliary for alkylation of C-H bonds is 8-aminoquinoline. Alkylation conditions involve heating of the substrate with alkyl iodide or benzyl bromide to 100-110 °C in t-amyl alcohol in the presence of K2CO3 base and catalytic amount of pivalic acid (Table 4). β-Alkylation of propionic acid amide can be performed with branched (entry 1) or straight-chain primary alkyl iodides (entry 2). The yields are moderate. Benzoic acid derivatives, in contrast, can be alkylated in good yields by alkyl iodides (entry 3) and benzyl bromides (entries 4 and 5). Acid-catalyzed removal of the directing group was also demonstrated affording the dialkylated benzoic acid in excellent yield (eq 3). Several examples of transition-metal-catalyzed sp2 C-H bond alkylation have been reported.17

|

(3) |

Table 4.

Alkylation of C-H Bondsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | amide | AlkI(Br) | major product | yield, % |

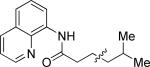

| 1 |

|

i-Butyl iodide |

|

58 |

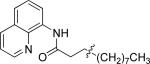

| 2 |

|

n-Octyl iodide |

|

47 |

| 3 |

|

n-Propyl iodide |

|

77 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

45 |

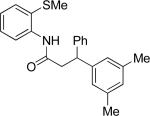

| 5 |

|

benzyl bromide |

|

64 |

Amide (1 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 equiv), base (2.5-3.5 equiv), pivalic acid (0.2 equiv), and RI or RBr (3-4 equiv) Yields are isolated yields. See the Supporting Information for details.

2.5. Mechanistic Considerations

2.5.1. Synthesis of Palladium Complexes

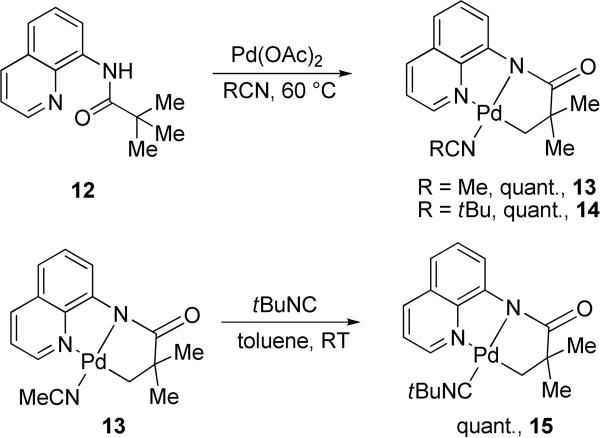

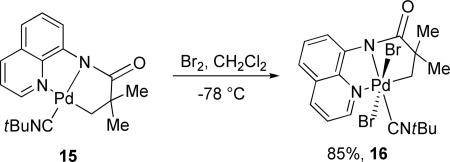

Several complexes that are related to potential reaction intermediates were synthesized and characterized (Scheme 2). Reaction of 8-aminoquinoline pivalamide with palladium acetate in nitrile solvents afforded the corresponding acetonitrile and pivalonitrile complexes 13 and 14 in quantitative yields. Notably, the cyclometalated complexes are easily formed in high yields under conditions where catalytic reaction is successful (entry 2, Table 2). Nitrile ligands are labile and can be easily replaced by t-butyl isonitrile to afford complex 15 in quantitative yield (Scheme 2). Complexes 13-15 were fully characterized by 1H and 13C-NMR as well as elemental analyses. Palladated methylene group signals appear in 1H-NMR spectra at 1.80-1.94 ppm (CDCl3 solvent). The complexes exist as yellow-brownish, crystalline solids that are stable at room temperature in air. They are soluble in most common organic solvents except pentane.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Nitrile and Isonitrile Complexes

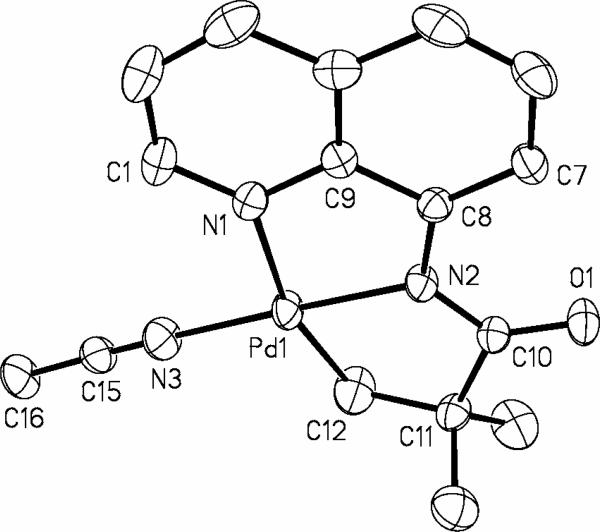

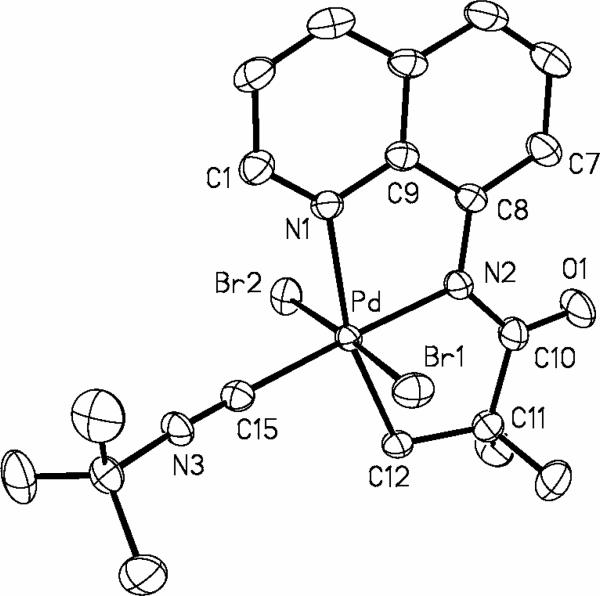

The structure of the complex 13 was verified by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. The ORTEP diagram of 13 is shown in Figure 1. Interestingly, 13 crystallizes in two different forms, orange blocks and yellow, thin plates. Both crystals were formed simultaneously upon slow diffusion of pentane into CH2Cl2 solution of 13 at -20 °C. Orange material is 13 that crystallizes in triclinic space group P-1, while the yellow plates is 13 that crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Cmca. Structure shown in Figure 1 is the orange material that has two independent molecules in the asymmetric unit, one of which is depicted. The Pd(1)-N(1)-C(9)-C(8)-N(2) five-membered ring is planar within four degrees. The other ring, Pd(1)-N(2)-C(10)-C(11)-C(12), assumes a puckered geometry, with C(11) forming the flap of an envelope and N(2)-Pd(1)-C(12)-C(11) dihedral angle is 18.3(5) deg. The N(2)-Pd(1)-C(12) angle is 83.3(2) deg showing distortion from an idealized square planar geometry at the palladium center. Several related crystalographically characterized palladium complexes that possess dianionic NNC ligands have been described in literature. Amino acid-derived (NNC)Pd complexes have been described by Beck.18 Espinet19 and an Italian group20 have also reported several ortho-palladated species resulting from NNC ligands. Layh has shown that facile cyclometalation of sp3 C-H bonds is observed in a monoanionic (NN)Pd system, affording an interesting PdNSiC heterocycle.21

Figure 1.

ORTEP view of 13. Selected interatomic distances (Å) and angles (deg): Pd(1)-N(2) = 1.969(4), Pd(1)-C(12) = 2.012(6), Pd(1)-N(3) = 2.013(5), Pd(1)-N(1) = 2.124(5), N(2)-Pd(1)-C(12)-C(11) = 18.3(5), N(2)-Pd(1)-C(12) = 83.3(2).

The reaction of 13 and 15 with bromine was investigated. If 13 was treated with Br2 at -78 °C, an unstable product that decomposed in solution at -40 °C within minutes was obtained. Reaction of 15 with bromine at -78 °C in CH2Cl2 afforded a green solution, from which palladium(IV) dibromide 16 was isolated in 85% yield after recrystallization from dichloromethane-pentane at -20 °C (eq 4). Complex 16 decomposes at 0 °C within hours in solution and within days in solid state. Relative stability of 16 may be explained by strong binding of the isonitrile ligand to palladium. It is known that d6 octahedral complexes often require dissociation of one ligand to decompose by reductive elimination pathways.22 Interestingly, the signal of palladated methylene group is shifted downfield compared with the corresponding signals for 13-15 and appears at 4.80 ppm in 1H spectrum.

|

(4) |

The dibromide 16 was isolated as dark-green crystalline blocks. Its structure was verified by X-ray crystallographic analysis. The five-membered Pd-N(2)-C(10)-C(11)-C(12) ring adopts an envelope conformation with C(11) forming the flap of the envelope (torsion angle Pd-N(2)-C(10)-C(11) = -5.5(4)°). An octahedral arrangement of ligands around Pd(IV) center is observed. The bromide ligands assume trans arrangement about the palladium center. While Pd(IV) complexes have been investigated quite extensively in recent years,23 it appears that no alkylpalladium(IV) dibromides have been crystallographically characterized. Some Pd(IV) dibromides possessing polydentate nitrogen or sulfur ligands have been described.24 It appears that the dianionic, tridentate NNC ligand stabilizes Pd(IV) oxidation state allowing for an efficient catalytic functionalization of C-H bonds and also for isolation of unusual and typically unstable high-valent Pd complexes. Unfortunately, attempts to replace the bromide substituent with an aryl or alkyl group have not been successful so far.

2.5.2. Mechanistic Studies

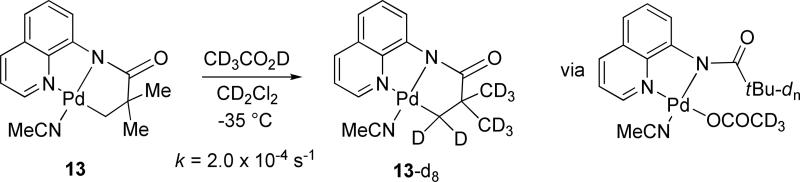

Upon dissolution of 13 in CD3CO2D, complete H/D exchange of the aliphatic hydrogens was observed within minutes at room temperature. The loss of alkyl hydrogen resonances in 13 with respect to time was measured by NMR at -35 °C in CD2Cl2 containing 40 equivalents of CD3CO2D. First-order rate constant k = 2.0 × 10−4 s−1 was obtained corresponding to ΔG‡ = 18 kcal/mol.

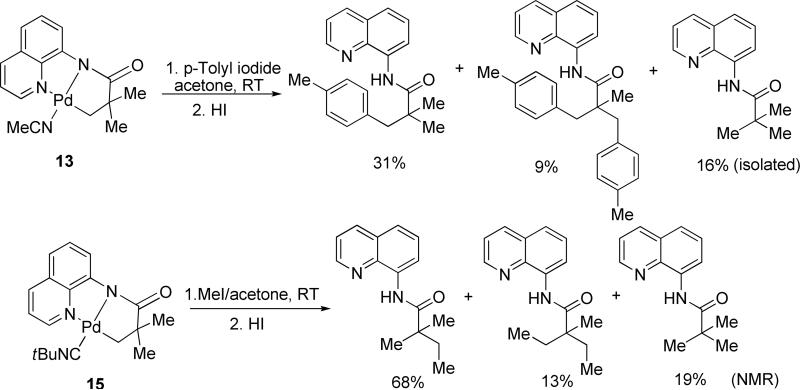

Complexes 13 and 15 were reacted with p-tolyl iodide and iodomethane, respectively, in acetone solvent at room temperature (Scheme 4). Following the treatment with HI to remove palladium, reaction mixture was either separated by preparative TLC (for arylation of 13) or analyzed by 1H NMR (for methylation of 15). A mixture of mono- and disubstitution products was obtained in addition to the recovered unreacted amide. This result shows that monomeric palladated complexes are capable of reacting with alkyl and aryl halides and are thus competent intermediates in the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 4.

Arylation and Alkylation of Palladated Intermediates

Pivalonitrile exchange was studied in CD2Cl2 solution at -35 °C by treatment of 14 with a large excess of CH3CN. The first-order rate constant obtained by using 10 equiv of CH3CN (kobs = 4.6 × 10−5 s−1) is about twice lower than the rate constant obtained using 20 equiv (kobs = 1.1 × 10−4 s−1). Thus it is clear that ligand displacement proceeds by an associative mechanism, consistent with the prevailing ligand substitution mechanism at square planar Pd(II) centers.

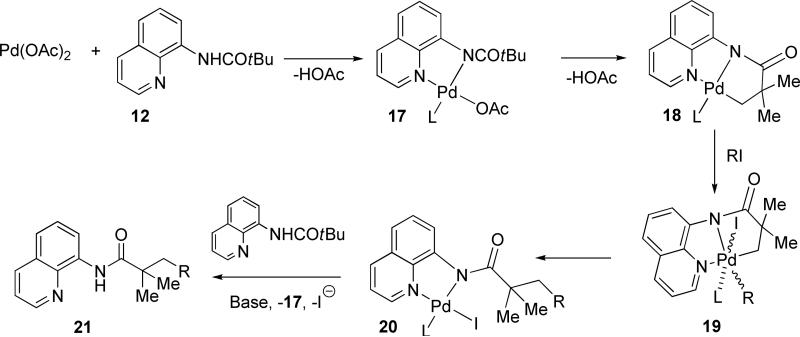

At this point a generalized mechanism for the auxiliary-directed arylation of C-H bonds can be proposed (Scheme 5). Palladium acetate reaction with 8-pivaloylaminoquinoline affords the palladium amide 17. The next step involves a rapid cyclometalation of t-butyl group resulting in the formation of 17. We have shown that only amides possessing an NH group are reactive;9b hence, formation of 17 is essential for the success of reaction. Oxidative addition of alkyl or aryl iodide to 18 produces 19. However, intermediacy of Pd(III) can not be excluded25 although formation of dimeric species is unlikely in strongly coordinating acetonitrile solvent. Reductive elimination followed by ligand exchange releases 21 and regenerates palladium amide.

Scheme 5.

Reaction Mechanism

3. Summary

We have developed a method for auxiliary-directed, palladium-catalyzed arylation and alkylation of sp3 and sp2 C-H bonds. Stoichiometric silver additives are not required in contrast with our previously reported procedure.9b Instead, simple inorganic bases can be employed and some reactions can be performed in alcohol/water mixtures. By employing 2-methylthioaniline auxiliary, selective monoarylation of primary sp3 C-H bonds can be achieved. If arylation of secondary sp3 C-H bonds is desired, 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary may be used. For alkylation of sp3 and sp2 C-H bonds, 8-aminoquinoline auxiliary affords the best results. A cyclometalated reaction intermediate has been isolated, structurally characterized, and its conversion to a Pd(IV) species investigated. A general reaction mechanism has been proposed involving formation of palladium amide, cyclometalation, oxidative addition, and reductive elimination steps. Detailed mechanistic studies of separate catalytic steps will be reported in future.

4. Experimental Section

General procedure for alkylation of C-H bonds

A 2-dram screw-cap vial was charged with Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol%), K2CO3 (2.5 equiv), substrate (1 equiv), pivalic acid (20 mol%), and alkyl iodide (3-4 equiv). The t-amyl alcohol (0.7 mL) solvent was added and the resulting mixture was stirred and heated at 100-110 °C for 12-26 h. The conversion was monitored by GC. After completion of reaction, ethyl acetate was added to reaction mixture followed by extraction with water. Aqueous layer was washed once with ethyl acetate. Combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4. Filtration and evaporation under reduced pressure followed by purification by flash chromatography gave products.

N-(5-Methylhexanoyl)-8-aminoquinoline (Table 4, entry 1)

The general procedure was followed using N-propionyl-8-aminoquinoline (140 mg, 0.7 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (7.8 mg, 0.035 mmol), K2CO3 (242 mg, 1.75 mmol), pivalic acid (14 mg, 0.14 mmol), and 2-methyliodopropane (240 μL, 2.1 mmol). Resulting mixture was heated for 22 h at 110 °C. Flash chromatography (toluene/EtOAc 50/1 to 25/1) gave 104 mg (58%) of a colorless oil, Rf=0.19 (toluene/EtOAc 50/1). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 9.82 (s, 1H) 8.83-8.78 (m, 2H) 8.17 (dd, 1H, J= 8.3, 1.7 Hz) 7.58-7.43 (m, 3H) 2.55 (t, 2H, J= 7.6 Hz) 1.89-1.77 (m, 2H) 1.63 (septet, 2H, J= 6.7 Hz) 1.37-1.28 (m, 2H) 0.92 (d, 6H, J= 6.7 Hz). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 172.1, 148.3, 138.5, 136.5, 134.8, 128.1, 127.6, 121.7, 121.5, 116.6, 38.7, 28.1, 23.8, 22.7. Signal for one aliphatic carbon could not be detected. FT-IR (neat, cm−1) υ 3353, 1687. Anal. calcd. for C16H20N2O: C 74.97, H 7.86, N 10.93. Found: C 74.83, H 7.91, N 10.93.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

ORTEP view of 16. Selected interatomic distances (Å) and angles (deg): Pd-N(2) = 1.981(3), Pd-C(15) = 1.993(4), Pd-C(12) = 2.072(3), Pd-N(1) = 2.171(3), Pd-Br(1) = 2.4411(5), Pd-Br(2) = 2.4690(5), N(1)- Pd-N(2)-C(8) = 2.0(2), Pd-N(2)-C(10)-C(11) = -5.5(4).

Scheme 3.

H/D Exchange Studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Welch Foundation (Grant No. E-1571), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant No. R01GM077635), A. P. Sloan Foundation, and Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation for supporting this research. We thank Dr. James Korp for collecting and solving the X-ray structures of 13 and 16.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE: Detailed experimental procedures, characterization data for new compounds, and X-ray crystallography data for 13 and 16. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.a Lewis JC, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1013. doi: 10.1021/ar800042p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Campeau L-C, Fagnou K. Chem. Commun. 2006:1253. doi: 10.1039/b515481m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ackermann L. Synlett. 2007:507. [Google Scholar]; d Chen X, Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1173. doi: 10.1039/b606984n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439. [Google Scholar]; g Daugulis O, Do H-Q, Shabashov D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1074. doi: 10.1021/ar9000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:174. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selected examples: Pivsa-Art S, Satoh T, Kawamura Y, Miura M, Nomura M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1998;71:467–473. Park C-H, Ryabova V, Seregin IV, Sromek AW, Gevorgyan V. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1159–1162. doi: 10.1021/ol049866q. Bellina F, Cauteruccio S, Mannina L, Rossi R, Viel S. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3997–4005. doi: 10.1021/jo050274a. Flegeau EF, Popkin ME, Greaney MF. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2717–2720. doi: 10.1021/ol800869g. Chiong HA, Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1449. doi: 10.1021/ol0702324. Liegault B, Lapointe D, Caron L, Vlassova A, Fagnou K. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1826. doi: 10.1021/jo8026565. Hachiya H, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1737. doi: 10.1021/ol900159a. Canivet J, Yamaguchi J, Ban I, Itami K. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1733. doi: 10.1021/ol9001587. Yotphan S, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1511. doi: 10.1021/ol900103a. Do H-Q, Khan RMK, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15185. doi: 10.1021/ja805688p. Dwight TA, Rue NR, Charyk D, Josselyn R, DeBoef B. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3137. doi: 10.1021/ol071308z.

- 3.Selected examples: Kakiuchi F, Kan S, Igi K, Chatani N, Murai S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1698. doi: 10.1021/ja029273f. Oi S, Fukita S, Inoue Y. Chem. Commun. 1998:2439. Bedford RB, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB, Limmert ME. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390037. Caron L, Campeau L-C, Fagnou K. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4533. doi: 10.1021/ol801839w. Cho SH, Hwang SJ, Chang S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9254. doi: 10.1021/ja8026295. Chen X, Li J-J, Hao X-S, Goodhue CE, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0570943. Chiong HA, Pham Q-N, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9879. doi: 10.1021/ja071845e. Desai LV, Stowers KJ, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13285. doi: 10.1021/ja8045519. Shi Z, Li B, Wan X, Cheng J, Fang Z, Cao B, Qin C, Wang Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5554. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700590.

- 4.a Phipps RJ, Gaunt MJ. Science. 2009;323:1593. doi: 10.1126/science.1169975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang Y-H, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5072. doi: 10.1021/ja900327e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones WD. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:4475. doi: 10.1021/ic050007n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selected examples: Dong C-G, Hu Q-S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:2289. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504310. Campeau L-C, Schipper DJ, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3266. doi: 10.1021/ja710451s. Ren H, Knochel P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3462. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600111. Dyker G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992;31:1023. Ishii Y, Chatani N, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. Organometallics. 1997;16:3615. Jun C-H, Hwang D-C, Na S-J. Chem. Commun. 1998:1405. DeBoef B, Pastine SJ, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6556. doi: 10.1021/ja049111e. Tsuchikama K, Kasagawa M, Endo K, Shibata T. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1821. doi: 10.1021/ol900404r.

- 7.a Dyker G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994;33:103. [Google Scholar]; b Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chaumontet M, Piccardi R, Audic N, Hitce J, Peglion J-L, Clot E, Baudoin O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15157. doi: 10.1021/ja805598s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chaumontet M, Piccardi R, Baudoin O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:179. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lafrance M, Gorelsky SI, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14570. doi: 10.1021/ja076588s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Liégault B, Fagnou K. Organometallics. 2008;27:484. [Google Scholar]; g Giri R, Maugel N, Li J-J, Wang D-H, Breazzano SP, Saunders LB, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3510. doi: 10.1021/ja0701614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Wang D-H, Wasa M, Giri R, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7190. doi: 10.1021/ja801355s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Watanabe T, Oishi S, Fujii N, Ohno H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1759. doi: 10.1021/ol800425z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen X, Goodhue CE, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12634. doi: 10.1021/ja0646747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9886. doi: 10.1021/ja903573p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Shabashov D, Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3657. doi: 10.1021/ol051255q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13154. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Reddy BVS, Reddy LR, Corey EJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3391. doi: 10.1021/ol061389j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Feng Y, Chen G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:958. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gou F-R, Wang X-C, Huo P-F, Bi H-P, Guan Z-H, Liang Y-M. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5726. doi: 10.1021/ol902497k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Lazareva A, Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5211. doi: 10.1021/ol061919b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shabashov D, Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4947. doi: 10.1021/ol0619866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See Footnote 13, ref. 9a.

- 14.See Supplementary Information for optimization data.

- 15.While simple arylpropionic acids may be obtained by a condensation of acetic anhydride with an aromatic aldehyde followed by hydrogenation, aliphatic or aromatic ketones as well as aliphatic aldehydes are not generally suitable substrates for the Perkins reaction. Rosen T. The Perkin Reaction. In: Trost BM, Fleming I, Heathcock CH, editors. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. Pergamon; Oxford, U.K.: 1991. pp. 395–408.

- 16.a Lafrance M, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16496. doi: 10.1021/ja067144j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang Q, Fazio A, Dai G, Campo MA, Larock RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7460. doi: 10.1021/ja047980y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Lapointe D, Fagnou K. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4160. doi: 10.1021/ol901689q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang Y-H, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6097. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ackermann L, Novak P, Vicente R, Hofmann N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6045. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Catellani M, Frignani F, Rangoni A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:119. [Google Scholar]; e Martins A, Lautens M. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5095. doi: 10.1021/ol802185x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f McCallum JS, Gasdaska JR, Liebeskind LS, Tremont SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:4085. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Schreiner B, Urban R, Zorgafidis A, Sünkel K, Polborn K, Beck AZ. Naturforsch. B. 1999;54:970. [Google Scholar]; b Böhm A, Schreiner B, Steiner N, Urban R, Sünkel K, Polborn K, Beck AZ. Naturforsch. B. 1998;53:191. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinet P, Alonso MY, Garcia-Herbosa G, Ramos JM, Jeannin Y, Philoche-Levisalles M. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:2501. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacchi A, Carcelli M, Costa M, Pelagatti P, Pelizzi C, Pelizzi G. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1996:4239. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowen RJ, Fernandes MA, Layh M. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:1230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams BS, Holland AW, Goldberg KI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:252. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a Canty AJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992;25:83. [Google Scholar]; b Racowski JM, Dick AR, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10974. doi: 10.1021/ja9014474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sobanov AA, Vedernikov AN, Dyker G, Solomonov BN. Mendeleev Commun. 2002;1:14. [Google Scholar]; d Amatore C, Catellani M, Deledda S, Jutand A, Motti E. Organometallics. 2008;27:4549. [Google Scholar]; e Guo R, Portscheller JL, Day VW, Malinakova HC. Organometallics. 2007;26:3874. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a Yamashita M, Ito H, Toriumi K, Toriumi K, Ito T. Inorg. Chem. 1983;22:1566. [Google Scholar]; b Blake AJ, Kathirgamanthan P, Toohey MJ. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;303:137. [Google Scholar]

- 25.a Powers DC, Geibel MAL, Klein JEMN, Ritter T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17050. doi: 10.1021/ja906935c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Deprez NR, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11234. doi: 10.1021/ja904116k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.