Abstract

This study examined daily stressors in adults aged 18 to 89 years (M = 49.6 years) over 30 days. We examined the role of individual factors (i.e., age, self-concept differentiation, perceived control) in physical and psychological reactivity to interpersonal, network, home, and health stressors. Findings were consistent with the perspective that adults were less reactive to stress on days they felt in control and that younger adults and adults with high self-concept differentiation (SCD) were more vulnerable to stress. Age, SCD, and daily perceived control, however, interacted with one another and findings varied by stressor type. For example, age differences in reactivity were moderated by SCD whereby older adults with low SCD were particularly resilient to home stressors. Also, whether perceived control buffered adults' reactivity to daily stress varied by age and SCD. For example, only adults with high SCD were psychologically reactive to network stressors and only on days they reported having low control. The findings emphasize the importance of considering how individual characteristics interact in varying ways to influence stress reactivity to different types of stressors.

Keywords: adulthood, self-concept differentiation, perceived control, daily stress, daily psychological distress, daily physical symptoms

Theorists have emphasized the importance of daily stressors for adults' well-being (Almeida, 2005; Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Adults' reactivity to daily stressors is influenced by the personal characteristics they bring to the stressful situations in their lives (Almeida; Stawski, Sliwinski, Almeida, & Smyth, 2008; Piazza, Charles, & Almeida, 2007). The present study considered two between-person characteristics that may moderate adults' emotional and physical reactivity to daily stress, namely age and self-concept differentiation, as well as a variable, within-person characteristic, namely adults' daily perceptions of control.

Between-Person Characteristics and Stress: Age and Self-Concept Differentiation

Research recognizes individual differences in stress reactivity. For example, researchers have considered how stress reactivity is influenced by age (Birditt, Fingerman, & Almeida, 2005; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007), neuroticism (Mroczek & Almeida, 2004), global control (Neupert et al.) and global stress (Stawski et al., 2008). Here we consider age and self-concept differentiation in stress reactivity.

Age and stress reactivity

In general, research suggests older adults are exposed to fewer stressors than younger adults (e.g., Almeida & Horn, 2004; Stawski et al., 2008). Evidence of age differences in reactivity to stress, however, is mixed. Mrozcek and Almeida (2004) found that older adults were more reactive to daily stress than younger adults, whereas Uchino, Berg, Smith, Pearce, and Skinner (2006) found that older adults were less reactive. Other research suggests there are no age differences in reactivity (Diehl & Hay, 2009a; Stawski et al.). These mixed findings could reflect numerous factors. Studies differ, for example, in outcomes, in participants' ages, and whether age differences in stressor exposure are considered.

Notably, age differences in reactivity could depend upon stressor type. In analyses that aggregated multiple types of stressors, Mroczek and Almeida (2004) found older age was associated with heightened reactivity to stress. Research drawing from the same sample, however, found age was associated with reduced reactivity to interpersonal stressors (Birditt et al., 2005; Neupert et al., 2007) and unrelated to reactivity to home, work, or network stressors (Neupert et al.). We did not, therefore, expect age to be associated with a consistent pattern of increased or decreased reactivity to stress, but rather that the association between age and reactivity would vary by stressor type.

Self-concept differentiation and stress reactivity

We also considered the role of self-concept differentiation (SCD) in stress reactivity. SCD reflects the extent to which individuals see themselves differently across different roles and domains of life (Block, 1961). The construct of SCD fits within a larger literature on how the structure and organization of self-knowledge influences self-regulation and psychological well-being (Higgins, 1996; Kling, Ryff, & Essex, 1997; Linville, 1987; Rafaeli Mor & Steinberg, 2002; Showers, Abramson, & Hogan, 1998).

Two main perspectives exist on the adaptive value of SCD and related constructs. Linville (1987) argued that greater differentiation of the self-concept is adaptive because the negative effects of stressors experienced in one role are less likely to “spill over” into other roles.1 Linville's perspective is consistent with Gergen's (1991) argument that individuals who are specialized within social roles (thus differentiated across roles) can respond more flexibly to role-specific demands. A contrasting perspective argues that greater differentiation is maladaptive (Diehl, Hastings, & Stanton, 2001; Donahue, Robins, Roberts, & John, 1993). This perspective emphasizes that individuals with lower differentiation have a sense of identity, continuity, and biographical meaningfulness over time that facilitates adaptation (cf. Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994). Having a sense of consistency and coherence across roles (i.e., low SCD) may allow individuals to draw more readily on achievements and coping strategies from one role when experiencing stress in another.

At present, most evidence supports the perspective that high SCD is maladaptive. In a review and meta-analysis, Rafaeli-Mor and Steinberg (2002) found that greater SCD was associated with more depressive symptoms and negative affect, and lower positive affect and self-esteem. Research that specifically focuses on SCD and related constructs in stress reactivity, however, is mixed. Elsewhere, we found that SCD did not moderate healthy adults' emotional reactivity to daily stressors (Diehl & Hay, 2009a) but that adults with cancer were less reactive to stressors when they had lower SCD (Diehl & Hay, 2009b). In research on a related construct, Zeigler-Hill and Showers (2007) found that individuals who described their self-concepts using both positive and negative attributes within roles (i.e., evaluatively integrated) were less reactive to daily stress than individuals who used primarily positive or negative attributes to describe themselves within roles (i.e., evaluatively compartmentalized). Such research suggests greater differentiation may be associated with increased stress reactivity. In contrast, however, McConnell, Strain, Brown, and Rydell (2009) found that individuals low in self-complexity (similar to low SCD) were more reactive to negative life events than individuals high in self-complexity (similar to high SCD). McConnell et al. however, also found that irrespective of negative life events, adults high in self-complexity had poorer psychological well-being than adults low in self-complexity. Together, these studies suggest that SCD will be associated with increased physical symptoms and psychological distress but it is unclear whether SCD will be associated with reactivity to stress.

Interaction of age and SCD

Research suggests that SCD and age may interact to influence stress reactivity. Specifically, Diehl et al. (2001) found that age moderated the association between SCD and psychological well-being, such that older adults with high SCD had poorer psychological well-being than younger adults with high SCD. These findings are consistent with theorists' arguments that individuals' self-representations are particularly important in old age (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994; Freund & Smith, 1999). Indeed, given high identity exploration in young adulthood (Arnett, 2000), high SCD scores may be more normative in younger versus older adults. Nonetheless, as young adults increasingly commit to adult social roles, the development of a coherent and internally consistent self-concept becomes an important indicator of positive adaptation and mental health (Diehl, Youngblade, Hay, & Chui, in press). Although empirical data are limited, theorists have argued that the adaptive value of a coherent self-concept continues through midlife and later adulthood (Brandtstädter & Greve; Greve & Wentura, 2003; Markus & Herzog, 1991). Among older adults, therefore, having high SCD may be particularly maladaptive. Consequently, we hypothesized that SCD would be negatively associated with well-being in general and that SCD would be more strongly associated with stress reactivity in older versus younger adults.

Within-Person Characteristics and Stress: Daily Perceptions of Control

Considerable research examines perceptions of control and well-being. Perceptions of control are a set of flexible and interrelated beliefs about outcomes and the forces that influence those outcomes including oneself, powerful forces, and luck (Skinner, 1995). Perceptions of control develop and change as individuals navigate events that confirm, or disconfirm, their beliefs about control (Cairney & Krause, 2008; Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell 1998). Theory and research suggest that adults' general perceptions of control are relatively stable and `trait-like'. Thus, some individuals always tend to perceive themselves as having more control than other individuals. Perceptions of control, however, are not invariant. Adults' perceptions of control vary across life domains (Lachman & Weaver, 1998) and exhibit long-term change (Cairney & Krause) and short-term variability (Eizenman, Nesselroade, Featherman, & Rowe, 1997). As Eizenman et al. have pointed out, adults' control beliefs, therefore, reflect “some stable interindividual differences (how they generally are) and some short-term intraindividual variability (how they are that day)” (p. 490).

Most existing research focuses on between-person differences in trait-like perceptions of control. Such research finds that individuals with greater perceived control report better physical and psychological well-being (Bandura, 1997; Lachman & Firth, 2004; Rodin & Timko, 1992) and are less reactive to daily stress (Hahn, 2000; Neupert et al., 2007). Regarding daily perceptions of control, elsewhere we found that daily perceived control was associated with negative affect but that it did not buffer reactivity to stress (Diehl & Hay, 2009a). Ong, Bergeman, and Bisconti (2005), however, found that daily perceptions of control buffered reactivity to daily stress among recently bereaved adults. Ong et al. argue that fast-varying states such as daily stress and daily perceptions of control may be better predictors of variable emotional states (e.g., daily anxiety) than more stable characteristics. We expected, therefore, that daily perceptions of control would be associated with daily well-being and would buffer psychological and physical reactivity to daily stressors.

Stressor Domain: Interpersonal, Home, Network, and Health Stressors

Theorists have examined reactivity to various stressors including interpersonal, work, network, and home stressors (e.g., Bolger et al., 1989; Neupert et al., 2007). Here, we examined how age, SCD, and daily perceptions of control interacted to influence adults' reactivity to interpersonal, home, network, and health stressors. Given the lack of research in this area we did not develop hypotheses for each possible interaction and stressor type. Rather, we explain why we considered these stressors and highlight some possible effects suggested by existing research.

Interpersonal stressors are more highly associated with daily well-being than other stressors (Bolger et al., 1989; Neupert et al., 2007). Research suggests that, compared to younger adults, older adults experience fewer interpersonal stressors and are less reactive to them (Birditt et al., 2005; Neupert et al.). Such age differences in reactivity do not appear to stem from age differences in stress exposure or social networks (Birditt et al.). Age differences may reflect hypothesized improvements in emotion regulation with age (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000) or be due to other variables that interact with age. Indeed, Neupert et al.'s research suggests that perceiving low control is more detrimental to younger adults' reactivity to interpersonal stressors than it is to middle-aged or older adults' reactivity.

Having high SCD may also heighten adults' reactivity to interpersonal stress. Showers and Ziegler-Hill (2007; Ziegler-Hill & Showers, 2007) and Donahue et al. (1993) found that adults with self-concept structures akin to high SCD had less stable romantic relationships. Research also shows that individuals high in neuroticism are highly reactive to interpersonal stress (Bolger & Schilling, 1991). Although neuroticism and SCD are not interchangeable (Diehl & Hay, 2007), they exhibit moderate overlap and are associated with similar outcomes including anxiety and depressive symptoms (Bigler, Neimeyer, & Brown, 2001; Costa & McCrae, 1980; Diehl et al., 2001; Watson, Gamez & Simms, 2005). Evidence suggests, therefore, that high SCD is associated with maladaptive interpersonal processes. Consequently, we expected SCD to be positively associated with reactivity to interpersonal stressors.

Home stressors, including family demands and responsibilities, are associated with anxiety (Evans & Steptoe, 2002), tension (Almeida, Wethington, & Chandler, 1999), and physical and psychological distress (Neupert et al., 2007). Although younger and middle-aged adults experience more home stressors than older adults (Almeida & Horn, 2004), Neupert et al. found no age differences in reactivity to daily home stressors. High perceptions of general control, however, appear to lessen individuals' emotional reactivity to home stressors (Neupert et al.; Serido, Almeida, & Wethington, 2004). We expected, therefore, that daily perceptions of control would buffer adults' reactivity to home stressors.

Stressors that happen to close friends or family members, called network stressors, also influence adults' daily mood and physical symptoms (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). Research by Neupert et al. (2007) suggests emotional reactivity to network stressors depends on age and perceived control. Specifically, Neupert et al. found that younger and middle-aged adults were more reactive to network stressors when they perceived low control, but that older adults' reactivity to network stressors was unrelated to their perceived control. Research suggests older adults perceive less control in their relationships with family and friends than younger adults (Hay & Fingerman, 2005). If older adults tend to expect lower control in their social ties, their perceptions of control may simply not be as relevant to their reactivity to network stressors. Compared to younger and middle-aged adults, therefore, we expected older adults' perceptions of control to play less of a role in buffering their reactivity to network stress.

We also considered health stressors. Events that threaten the physical health of individuals are highly distressing (Almeida, 2005), and health problems increase with age (Jette, 1996; Manton, 1997: Wolff, Starfield, & Anderson, 2002). Nonetheless, age may not increase reactivity to health stressors. For instance, Fiske, Gatz, and Pederson (2003) found that age did not increase the relevance of health for depressive symptoms. Indeed, older adults may interpret a certain degree of health stress as normative and be better able to accommodate health limitations than younger adults (Piazza et al., 2007). Regarding the role of daily perceptions of control in stress reactivity, numerous studies suggest that general and health-specific perceptions of control influence health outcomes and buffer reactivity to stress (e.g., Bollini, Walker, Hamman, & Kestler, 2004; Chung, Preveza, Papandreou, & Prevezas, 2006). Thus, we did not expect age differences in reactivity to health stressors but we expected that adults' daily perceptions of control would buffer their reactivity to health stressors.

In sum, relatively little research examines how risk factors influence reactivity across stressor types. Here we extend existing research by considering how age, SCD, and daily perceptions of control influenced reactivity to four types of stressors in an age diverse sample of adults. In general, we expected that individuals would be less reactive to all stressors on days they felt in control and that adults with lower SCD would be less reactive to daily stressors. We also expected that age differences in reactivity and the interaction of age, SCD, and perceived control would vary by stressor type.

Method

Participants

The sample included 120 men and 119 women aged 18 to 89 years (M = 49.6, SD = 19.6) recruited in North Central Florida. Screening interviews established that participants did not have major sensory impairments, concurrent depression, a history of severe mental illness, and were physically and cognitively able to participate. Twenty-five percent of participants were recruited through random digit dialing, 25% through letters of invitation to University of Florida alumni, 45% though convenience methods (e.g., flyers, newspaper ads) and 5% through a retirement community.

Approximately equal numbers of men and women were recruited in 3 age groups: young adults (n = 81, aged 18–39 years), middle-aged adults (n = 81, aged 40–59 years), and older adults (n = 77; aged 60 plus). To achieve a balanced distribution of gender, we oversampled middle-aged and older men using letters of invitation and flyers. Most of the participants were Caucasian (88%) and the median reported income was $35,000–50,000. Most young adults (73%) were single; most middle-aged (65%) and older adults (62 %) were married. Forty-five percent of young adults were employed and 55% were students; 90% of middle-aged adults were employed and 68% of older adults were retired.

Procedure

Participants completed a 2 to 3 hour individual baseline session followed by 30 consecutive daily phone interviews and diaries. Trained interviewers conducted the baseline sessions and daily phone interviews. The research team included 30 interviewers; to minimize the likelihood of any particular interviewer's style influencing a participant's answers, participants were interviewed by an average of 10 interviewers over the 30 days (range 6 –14, SD = 1.6). Interviews were conducted each evening between 4–9 pm and interviewers were regularly monitored to ensure they followed correct interviewing procedures. Participants were instructed to self-administer the diaries each evening; 85% of the diaries were completed after 5:00 pm and most (73%) were completed after the phone interview. Participants were instructed to mail the diaries the day after completing them. Participants were paid $20 for the baseline session and $8 for each completed diary, for a possible maximum of $260.

The final sample included 239 participants with 6,715 days of valid data. Data monitoring revealed that participants who did not complete the majority of the daily protocol frequently did not follow correct procedures (e.g., completing multiple diaries at once). Consequently, data from 44 participants who failed to complete at least 24 dairies and/or 24 interviews were excluded. Baseline data from these participants were compared to data from the 239 final participants. Excluded participants were younger, F(1, 282) = 8.10, p < .05 and exhibited scores indicative of poorer well-being on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), F(1, 282) = 13.60, p < .001, the negative affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson, Clarke, & Tellegen, 1988), F(1, 282) = 11.00, p < .001, and the Self-Acceptance and Purpose in Life subscales of Ryff's (1989) Scales of Psychological Well-being, F(1, 282) = 5.10 and F(1, 282) = 4.10, both p's < .05, respectively.

Measures

Between-Person Independent Variables

Self-concept differentiation

SCD was assessed during the baseline session using Block's (1961) self-concept differentiation index. Participants rated how characteristic 40 self-attributes (e.g., selfish, considerate) were of (a) their true self and themselves with their (b) family, (c) spouse or significant other, (d) a close friend, and (e) a colleague (1 = extremely uncharacteristic, 8 = extremely characteristic). Participants who did not currently have a romantic partner or colleague were instructed to think of what they were like in those relationships in the past.

Each participant's ratings were correlated and subjected to a within-person principal components analysis. The first component extracted represented the variance shared by the 5 self-representations. The SCD index was estimated by subtracting this variance from 1.0; higher scores indicate greater SCD. This measure has been used in studies including young, middle-aged, and older adults (e.g., Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993) and its reliability and construct validity have been established. For example, the SCD index shows significant inverse relations with self-concept related constructs that have a contrary meaning including self-esteem, self-concept clarity, and self-acceptance and it shows significant positive correlations with constructs such as anxiety, depression, and neuroticism (Diehl et al.; Donahue et al.; Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, 1997). Significant correlations between SCD and related constructs, however, are moderate suggesting that conceptual overlap with potentially confounding constructs is small. Descriptive data are presented in Table 1; the mean SCD scores were consistent with those reported in previous research (e.g., Donahue et al.; Diehl et al.).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Proportion of Days with Different Stressor Types by Age Group

| Young adults (n = 81) | Middle-aged adults (n = 81) | Older adults (n = 77) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | |||

| Age | 26.1a (5.9) | 52.4b (4.7) | 71.4c (7.8) |

| Self-concept differentiation (SCD) | .19a (.10) | .16a,b (.10) | .14b (.11) |

| Daily control | 17.7a (2.6) | 18.2a,b (2.8) | 19.1b (2.1) |

| Daily psychological distress | 2.4a (2.3) | 1.9a,b (2.3) | 1.3b (2.1) |

| Daily physical symptoms | 4.1a (2.2) | 3.7a,b (2.6) | 2.1b (3.7) |

| Mean Proportion of Days Characterized by Stressor Types | |||

| Interpersonal stress | .18a | .20a | .17a |

| Health stress | .07a | .08a | .12b |

| Network stress | .06a | .07a | .08a |

| Home stress | .15a | .15a | .15a |

Note. Means of daily values were first estimated within-person (i.e., across study days) then within age groups. Means in the same row that do not share subscripts differ at p < .05 in the Tukey honestly significant difference comparison.

Within-Person Independent Variables

Daily stress

During phone interviews participants completed the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE), a semi-structured interview developed on a nationally representative sample of adults aged 25 to 74 (Almeida et al., 2002). The DISE assesses the occurrence of daily stressors in various life domains. Here we consider: (a) interpersonal stressors (i.e., actual and avoided arguments) (b) network stressors (i.e., stressors that occur to participants' close friends or family that are stressful for them), (c) personal health stressors, and (d) home stressors (e.g., home demands and family responsibilities). Each day participants indicated whether they experienced each of these stressor types by answering yes (1) or no (0) to a series of forced-choice questions (e.g., Did you have an argument or disagreement with anyone today?). Similar to data reported by Almeida et al., participants reported none of these stressors on 59% of the days; 1 on 33% of the days, and 2 or more on 8% of the days. Age differences in the mean proportion of days participants experienced the stressors were only found for health stressors, which older adults reported experiencing more often than middle-aged and younger adults (Table 1).

Daily perceptions of control

Participants reported their perceptions of control in the daily diaries using Eizenman et al.'s (1997) locus of control subscale. This 4-item scale assesses the extent to which individuals perceive events to be in their control versus external forces. Statements were modified to focus on the past 24 hours; participants indicated their agreement on a scale of 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). Higher scores reflect greater control. Eizenman et al. established the reliability and validity of this measure and its utility in repeated measurement designs. Internal consistency coefficients estimated on 5 randomly selected days suggest the measure has moderate internal consistency (M = .72, SD = .05, Range: .64 to .75). Older adults had higher levels of mean daily control than younger adults (Table 1).

Dependent Variables

Daily psychological distress

Each day participants completed the depression subscale of the Profile of Mood States-Short Form (POMS; Curran, Andrykowski, & Studts, 1995). Respondents indicated how often they felt each of 8 mood states (e.g., sad, discouraged) in the past 24 hours on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Daily subscale scores range from 0 to 32; higher scores indicate greater symptoms. This subscale includes items similar to those used to assess psychological distress by daily stress researchers (e.g., Neupert et al., 2007). Past research supports the validity and reliability of the POMS (Curran et al.) and Cranford et al. (2006) demonstrated the utility of a 3-item POMS measure for reliably capturing daily changes in moods. As Cranford et al. note, researchers should use the longest possible measure to increase reliability and ensure they do not restrict the conceptual range of the construct. Here, we estimated internal consistency coefficients on 5 randomly selected days (M = .86, SD = .03, Range: .83 to .89). These data and Cranford et al.'s research suggest the POMS depression subscale is a reliable indicator of daily depressive mood. In this study, younger adults reported higher average daily psychological distress than older adults (Table 1).

Daily physical symptoms

Each day participants completed the Physical Symptoms Checklist, a short version of Larsen and Kasimatis' (1991) comprehensive symptom checklist. Participants indicated how frequently they experienced 11 physical symptoms (e.g., headaches, backaches, nausea) over the past 24 hours (recoded so 0 = none of the time, 4 = all of the time). Almeida et al. (2002) have demonstrated the utility of this checklist in daily stress studies. In this study, younger adults reported higher average daily physical symptoms than older adults (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

Multilevel models (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999) tested the association of within- and between-person variables and daily physical symptoms and psychological distress. Age and SCD were between-person centered and daily perceptions of control were within-person centered (Singer & Willet, 2003). To minimize the influence of reverse causation on the findings, our models included the day-before outcome as an additional predictor (Grzywacz, Almeida, Neupert, & Ettner, 2004; Ong & Allaire, 2005). The disadvantage of such models is that the influence of SCD and age may be attenuated because part of their effect may occur indirectly through their influence on prior-day physical symptoms or psychological distress (see Grzywacz et al.). Thus, these models represent a conservative test of the hypothesized relationships.

Using physical symptoms as an example, the within-person model (i.e., level 1) was:

| (1) |

β0j is a person's physical symptoms on a day with no stress and their average control. β1j is the association between prior-day physical symptoms and current-day physical symptoms for person j. Analogously, β2j is the stress-physical symptom association for person j (i.e., their stress reactivity) and β3j is the control-physical symptoms relationship for person j (i.e., their sensitivity to control). Finally, β4j indicates whether person j's perceptions of control buffer his or her reactivity to stress. Because testing some of the hypothesized moderation effects required 3-way interactions, all 2-way interactions were included. The random residual component is represented by eij.

At the between-person level (i.e., level 2), we examined the role of age and SCD in adults' reactivity to stress and sensitivity to control:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Equation 2 describes the role of SCD (γ01), age (γ02), and their interaction (γ03) on adults' average daily physical symptoms (β0j). Equation 3 describes the influence of SCD (γ11) and age (γ22) on the association between prior- and current-day physical symptoms (β1j). Similarly, equations 4 and 5, examine the influence of SCD and age on reactivity to stress (γ21,and γ22) and sensitivity to control (γ31). and γ32). Equations 4 and 5 also examine age differences in the association between SCD and stress reactivity (γ23), and SCD and sensitivity to control (γ33). Equation 6 tests whether daily control buffers reactivity to stress (γ40) and whether that effect is moderated by SCD (γ41) and age (γ42). Equations 7 and 8 were included for completeness given the testing of higher-order interactions. μ0j through μ6j represent the unexplained variance in participants' random intercepts and slopes.

Significant interactions were decomposed using methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991) and Preacher and colleagues (Preacher, 2006; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). For illustrative purposes, interactions involving age and SCD are presented for low and high values that correspond to 1 SD below and above the variable mean. For interactions involving stressors, we compared days that individuals experienced stress with days they did not.

Results

Unconditional models revealed that 41% of the variance in psychological distress was between-person (τ00 = 4.96, z = 10.39, p < .001) and 59% was within-person (σ2 = 7.22, z = 56.75, p < .001). For physical symptoms, 56% of the variance was between-person (τ00 = 5.42, z = 10.63, p < .001) and 44% was within-person (σ2 = 4.25, z = 56.84, p < .001). Thus, there was sufficient variability to justify multilevel analyses. Regarding daily control, 70% of the variance was between-person (τ00 = 7.82, z = 10.77, p < .001) and 30% was within-person (τ00 = 3.30, z = 56.90, p < .001).

Next, we modeled the effect of daily stress, daily control, and age and SCD on psychological distress (Table 2) and physical symptoms (Table 3). To minimize the model complexity and facilitate the comparison of our findings with those of Neupert et al. (2007), we examined each stressor in a separate model. Consequently, each model included common effects (i.e., effects not specific to a particular stressor). To avoid reporting spurious findings, we only present common effects that were observed in at least half of the models for each outcome.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Estimates and Standard Errors of Psychological Reactivity to Stressors

| Stress Domain |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Interpersonal | Home | Network | Health | |

| Well-being (β0) | |||||

| Intercept | γ 00 | 1.32 (0.11)*** | 1.30 (0.10)*** | 1.37 (0.11)*** | 1.37 (0.11)*** |

| SCD | γ 01 | 5.14 (0.97)*** | 5.45 (0.98)*** | 5.68 (0.97)*** | 5.73 (1.02)*** |

| Age | γ 02 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Age X SCD | γ 03 | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) |

| Prior-day psychological distress (β1) | |||||

| Distresst-1ij | γ 10 | 0.16 (0.02)*** | 0.16 (0.02)*** | 0.16 (0.02)*** | 0.15 (0.02)*** |

| SCD X Distresst-1ij | γ 11 | 0.15 (0.18) | 0.09 (0.18) | 0.12 (0.18) | 0.09 (0.17) |

| Age X Distresst-1ij | γ 12 | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0. 01 (0.00)* | −0.01 (0.00)* |

| Stress (β2) | |||||

| Stresstij | γ 20 | 0.32 (0.10)** | 0.66 (0.12)*** | 0.58 (0.17)*** | 0.53 (0.16)** |

| SCD X Stresstij | γ21 | 0.37 (0.86) | 1.60 (1.06) | 0.22 (1.57) | −0.44 (1.30) |

| Age X Stresstij | γ 22 | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Age X SCD X Stresstij | γ23 | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.06)* | 0.03 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.07) |

| Control (β3) | |||||

| Controltij | γ30 | −0.34 (0.04)*** | −0.35 (0.04)*** | −0.39 (0.04)*** | −0.37 (0.04)*** |

| SCD X Controltij | γ 31 | −0.35 (0.41) | −0.95 (0.40)* | −0.73 (0.35) | −0.92 (0.35)** |

| Age X Controltij | γ 32 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.00) |

| Age X SCD X Controltij | γ 33 | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.02) |

| Stress and Control (β4) | |||||

| Stresstij X Controltij | γ 40 | −0.21 (0.06)*** | −0.16 (0.07)* | −0.04 (0.09) | −0.10 (0.07) |

| SCD X Stresstij X Controltij | γ 41 | −0.67 (0.61) | 0.62 (0.69) | −1.22 (1.04) | 1.40 (0.71)* |

| Age X Stresstij X Controltij | γ 42 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.00) |

| Prior-day psychological distress and stress (β5) | |||||

| Distresst-1ij X Stresstij | γ 50 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) |

| Prior-day psychological distress and control (β6) | |||||

| Distresst-1ij X Controltij | γ 60 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

Note. Same-day effects are noted with the subscript t; prior-day effects are noted with the subscript t-1.Within-person effects of stress and control are indicated with the subscript ij; between-person effects with the subscript j.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Unstandardized Estimates and Standard Errors of Physical Reactivity to Stressors

| Stress Domain |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Interpersonal | Home | Network | Health | |

| Well-being (β0) | |||||

| Intercept | γ 00 | 2.26 (0.09)*** | 2.27 (0.09)*** | 2.27 (0.09)*** | 2.23 (0.09)*** |

| SCD | γ 01 | 2.82 (0.86)** | 2.63 (0.87)** | 2.69 (0.85)** | 2.62 (0.89)*** |

| Age | γ 02 | −0.02 (0.00)*** | −0.01 (0.01)*** | −0.01 (0.00)*** | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Age X SCD | γ 03 | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.05) |

| Prior-day physical symptoms (β1) | |||||

| Symptomst-1ij | γ 10 | 0.35 (0.02)*** | 0.33 (0.02)*** | 0.34 (0.02)*** | 0.32 (0.02)*** |

| SCD X Symptomst-1ij | γ 11 | 0.17 (0.18) | 0.16 (0.18) | 0.18 (0.18) | 0.20 (0.17) |

| Age X Symptomst-1ij | γ 12 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0. 00 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.00) |

| Stress (β2) | |||||

| Stresstij | γ 20 | −0.06 (0.11) | 0.20 (0.12) | −0.17 (0.17) | 1.45 (0.19)*** |

| SCD X Stresstij | γ 21 | −0.37 (0.72) | 1.34 (0.79) | 0.65 (1.18) | −0.65 (1.27) |

| Age X Stresstij | γ 22 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.04 (0.01)*** |

| Age X SCD X Stresstij | γ 23 | −0.04 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.00 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Control (γ3) | |||||

| Controltij | γ 30 | −0.10 (0.02)*** | −0.10 (0.03)*** | −0.10 (0.03)*** | −0.09 (0.02)*** |

| SCD X Controltij | γ 31 | −0.14 (0.20) | −0.02 (0.21) | 0.01 (0.17) | −0.19 (0.18) |

| Age X Controltij | γ 32 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00)* | 0.01 (0.00)* | 0.01 (0.00) |

| Age X SCD X Controltij | γ 33 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Stress and Control (γ4) | |||||

| Stresstij X Controltij | γ 40 | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.12 (0.06)* |

| SCD X Stresstij X Controltij | γ 41 | 0.27 (0.38) | −0.29 (0.44) | −1.65 (0.68)* | 0.01 (0.50) |

| Age X Stresstij X Controltij | γ 42 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) |

| Prior-day psychological distress and stress (β5) | |||||

| Symptomst-1ij X Stresstij | γ 50 | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) |

| Prior-day psychological distress and control (β6) | |||||

| Symptomst-1ij X Controltij | γ 60 | −0.00 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) |

Note. Same-day effects are noted with the subscript t; prior-day effects are noted with the subscript t-1.Within-person effects of stress and control are indicated with the subscript ij; between-person effects with the subscript j.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Common effects

Across all models, SCD was associated with increased psychological distress and physical symptoms (γ01; Tables 2 and 3 and age was negatively associated with physical symptoms in 3 of 4 models (γ02; Table 3). In addition, higher perceived control was associated with decreased psychological distress and physical symptoms (γ30; Tables 2 and 3).

The interaction between SCD and daily control influenced psychological distress (γ31; Table 2). Analyses revealed that the association between increased daily control and decreased psychological distress was stronger among individuals with high SCD. Specifically, for adults 1 SD above the mean SCD score, the association between daily control and psychological distress was b = −.55, p < .05, whereas for adults 1 SD below the mean, the association was b = −.35, p < .05.

Age also moderated the association between daily control and physical symptoms (γ32; Table 3). Among adults 1 SD below the mean age (i.e., 30 years old, roughly corresponding to young adulthood) increased perceived control was associated with decreased physical symptoms (b = −0.04, p < .05). In contrast, among adults 1 SD above the mean age (i.e., 59 years old, roughly corresponding to older adulthood) increased perceived control was associated with increased physical symptoms (b = 0.07, p < .001).

Reactivity to interpersonal stressors

The association between interpersonal stressors and psychological distress was moderated by daily control (γ20, γ40; Table 2). Specifically, on low control days, interpersonal stressors were associated with increased psychological distress (b = .92, p < .001), whereas on high control days, interpersonal stressors were not associated with increased psychological distress (b = −0.04, ns).

Reactivity to home stressors

The association between home stressors and psychological distress was moderated by daily control (γ20, γ40; Table 2). Specifically, on low control days, home stressors were associated with increased psychological distress (b = 1.0, p < .01). In contrast, on high control days, home stressors were not associated with psychological distress (b = 0.31, ns).

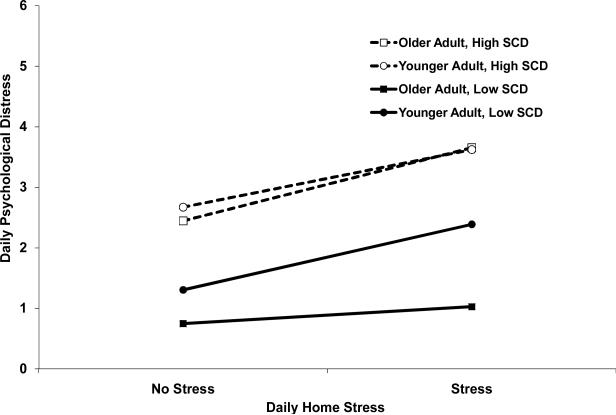

In addition, psychological and physical reactivity to home stressors was influenced by the interaction of age and SCD (γ23; Tables 2 and 3). As shown in Figure 1, home stressors were associated with increased psychological distress in young adults with high and low SCD (b = 0.95 and b = 1.8, respectively, both p's < .01). In contrast, home stressors were only associated with increased psychological distress among older adults with high SCD (b = 1.21, p < .01) but not older adults with low SCD (b = .28, ns).

Figure 1.

The influence of age and SCD on psychological reactivity to home stressors.

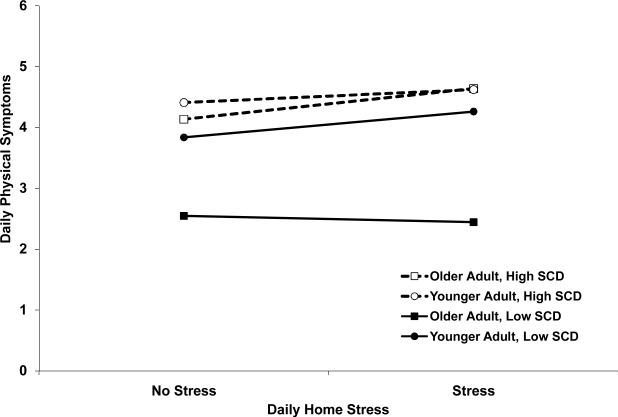

Decomposing the Age X SCD X Home Stress interaction for physical symptoms revealed a slightly different pattern (γ23; Table 3, Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, younger adults with low SCD experienced increased physical symptoms as a result of home stressors (b = .43, p < .05) as did older adults with high SCD (b = .50, p < .05). In contrast, younger adults with high SCD and older adults with low SCD were not physically reactive to home stressors (b = −.10, ns, and b = .21, ns, respectively).

Figure 2.

The influence of age and SCD on physical reactivity to home stressors.

Reactivity to network stressors

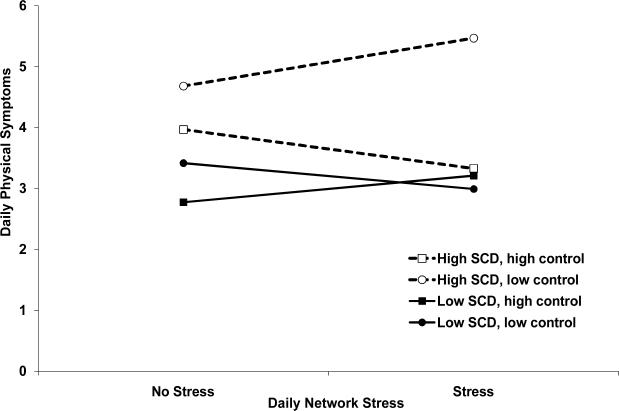

Network stressors were associated with increased psychological distress (γ20; Table 2); this association was not moderated by SCD, age, or perceived control. Physical reactivity to network stressors was, however, moderated by SCD (γ41; Table 3). As shown in Figure 3, among individuals with low SCD, network stressors were not associated with increased physical symptoms on low or high control days (b = −.42, ns, and b = .44, ns, respectively). Among individuals with high SCD, network stressors were associated with increased physical symptoms on low control days (b = 0.79, p < .05) and decreased physical symptoms on high control days (b = −0.64, p < .05).

Figure 3.

The influence of SCD and daily control on physical reactivity to network stressors.

Reactivity to health stressors

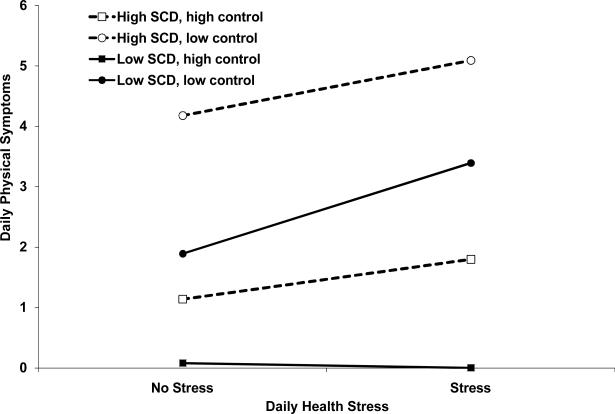

Health stressors were associated with increased psychological distress and physical symptoms (γ20; Tables 2 and 3). Psychological reactivity to health stressors was moderated by SCD and control (γ41; Table 2). As shown in Figure 4, among individuals with high SCD scores, health stressors were associated with increased psychological distress on low control days (b = .91, p < .05) and high control days (b = .66, p <.05). In contrast, among individuals with low SCD scores, health stressors were only associated with increased psychological distress on low control days (b = 1.50, p < .05 compared to b = −.27, ns, on high control days).

Figure 4.

The influence of age and daily control on physical reactivity to health stressors.

Daily control and age also moderated physical reactivity to health stressors. Specifically, health stressors were associated with a greater increase in physical symptoms on low versus high control days (b = 1.80 and b = 1.23, respectively, both p's < .05). Health stressors were also associated with a greater increase in physical symptoms among younger versus older adults (b = 2.6 and b = 1.1, respectively, both p's < .05).

Unreported models

Consistent with past research (e.g., Neupert et al., 2007) we estimated additional models controlling for gender and years of education. Also, to facilitate the separation of within- and between-person variance (Stawski et al., 2008) and to control for differences in exposure to stress, we estimated models including individuals' mean stress and mean perceived control as additional level-2 variables. The findings were unchanged.

Discussion

This study examined the role of age, SCD, and perceived control in the daily stress process. We focused on three commonly considered domains of stress, namely interpersonal, home, and network stressors. We also considered health stressors, which have been relatively under-examined in the daily stress literature. Age, SCD, and perceived control were directly associated with daily psychological distress and physical symptoms and influenced stress reactivity in varying ways.

The Role of Age and SCD in Daily Psychological Distress and Physical Symptoms

Consistent with past research (c.f., Carstensen, Mikels, & Mather, 2006), older adults experienced lower average psychological distress than younger adults. Furthermore, in keeping with research showing that age is positively associated with health problems (Manton, 1997; Wolff et al., 2002), older adults reported more health stressors than younger adults. Nonetheless, older adults also reported slightly lower mean physical symptoms than younger adults. This finding could reflect that older adults may perceive some degree of physical symptoms as normative (Piazza et al., 2007) and have a higher threshold for reporting them (Leventhal & Crouch, 1997).

Older adults also had more coherent self-concepts (i.e., lower SCD) than younger adults, which is consistent with Diehl et al.'s (2001) research showing that SCD is relatively high in young adulthood. Such age differences could reflect that young adulthood is characterized by high identity exploration (Arnett, 2000; Kroger, 2006). In contrast to Diehl et al. and our expectations, however, we did not find age differences in the direct association between SCD and psychological distress or physical symptoms. Thus, even if high SCD is more normative in younger adulthood, it appears to be similarly associated with lower well-being at all stages of adulthood.

The Role of Daily Control in Daily Psychological Distress and Physical Symptoms

Our findings suggest that age is associated with slightly increased daily perceived control. This finding is consistent with research by Lachman and Weaver (1998) showing age is positively associated with adults' global control but it is contrary to research suggesting age is negatively associated with global control (Ross & Mirowsky, 2002; Cairney & Krause, 2008). Beliefs about perceived control are multifaceted, however, and age is associated with increased control in some areas (e.g., work) and decreased control in others (e.g., relationships with children; Brandstädter & Rothermund, 1994; Lachman & Weaver; Nurmi, Pulliainen, & Salmelo-Aro, 1992). Our findings suggest that on a day-today basis, in the absence of major life events, older adults may find ways to maximize their perceived control.

As expected, and similar to Neupert et al. (2007), increased perceptions of control were associated with decreased physical symptoms among younger, but not older, adults. Age differences in coping behavior may underlie these findings. Specifically, Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, and Novacek (1987) found that younger adults perceived events to be more changeable and favored active, problem-focused coping strategies, whereas older adults perceived events to be less changeable and favored more intrapersonal, emotion-focused strategies (e.g., acceptance). Birditt et al.'s (2005) research on interpersonal stressors also suggests younger adults are more likely than older adults to use active coping strategies. Such age differences, whereby younger adults perceive events to be more changeable and adopt more problem-focused coping strategies, could explain why they benefit from perceiving increased control and older adults do not.

Indeed, among older adults, greater perceived control was associated with increased physical symptoms. The reason for this finding is unclear. Perhaps older adults perceive barriers to their ability to exert control. Indeed, Lachman and Weaver (1998) found that older adults reported higher control and higher constraints than younger adults. Alternatively, much as the common experience of physical ailments in later adulthood (e.g., Wolff et al., 2002) may lead older adults to have a higher threshold for reporting physical symptoms (Leventhal & Crouch, 1997) it may also lead older adults to feel more control over the relatively minor physical symptoms considered here (e.g., upset stomach). Perhaps when faced with heightened physical symptoms, older adults may remind themselves how they have coped with such symptoms in the past, thereby, emphasizing their sense of control.

Our findings also showed that the association between control and psychological distress was moderated by SCD. Specifically, the ability of perceived control to decrease psychological distress was stronger among adults with high SCD. This pattern may reflect several factors. First, compared to adults with low SCD, adults with high SCD report significantly more daily psychological distress in general and, thus, have more room for improvement. As well, adults with high SCD are more variable in their daily emotional states (Diehl & Hay, 2009a) and feel less control over their lives (Donahue et al., 1993) than adults with low SCD. This increased emotional lability and tendency towards perceiving low control, may lead individuals with high SCD to experience particularly profound improvements in well-being when they do feel in control. These individuals, however, also experience particularly high psychological distress on days they perceive low control.

Age, SCD, Control and Psychological and Physical Reactivity to Stress

Similar to past research, we found that daily stressors were associated with increased psychological distress and physical symptoms (Hahn, 2000; Neupert et al., 2007; Stawski et al., 2008). Reactivity to stress, however, was influenced by age, SCD, and perceived control and varied across stressor type.

Interpersonal stressors

Adults were psychologically but not physically reactive to interpersonal stressors. Contrary to past research (Birditt et al., 2005; Neupert et al., 2007), we found no age differences in reactivity to interpersonal stressors. Also contrary to our expectations, SCD did not moderate individuals' reactivity to impersonal stressors.

Our findings were consistent with Neupert et al.'s (2007) research showing perceptions of control moderate adults' psychological reactivity to interpersonal stressors. Specifically, interpersonal stressors were not associated with increased psychological distress when adults perceived high daily control. In contrast, when adults perceived low daily control, interpersonal stressors were associated with increased psychological distress. These findings are consistent with numerous studies showing the importance of perceived control for well-being and stress reactivity (e.g., Bandura, 1997; Hahn, 2000; Lachman & Firth, 2004; Ong et al., 2005). Indeed, our inclusion of daily control may help explain why age and SCD failed to moderate reactivity to interpersonal stressors. Perhaps by assessing a key risk factor on a daily basis and in high proximity to the daily stress itself, more distal moderating factors such as age and SCD are less relevant. Alternatively age differences in reactivity to daily stressors may be small and, thus, detected more readily in studies with more power to test between-person differences (i.e., studies with large level-2 samples; Snijders, 2005). For instance, although they did not focus on interpersonal stressors, Stawski et al. (2008) found no age differences in reactivity to daily stress using a sample similar in size to this study. Finally, the role of moderating factors such as age and SCD may be more apparent when adults experience highly stressful events rather than day-to-day hassles. For example, some research suggests that self-perceptions play a role in coping with major stressors such as cancer (Taylor, Lichtman, & Wood, 1984).

Home stressors

As expected and consistent with past research (Neupert et al., 2007; Serido et al., 2004), home stressors were only associated with increased psychological distress on days adults perceived low control. This association also depended on age and SCD. Specifically, older adults with low SCD did not experience increased psychological reactivity to home stressors although older adults with high SCD, and all young adults, did. The findings for physical reactivity to home stressors were similar, although young adults with high SCD did not report increased physical symptoms as a result of home stressors. This latter finding may reflect that, compared to other adults, young adults with high SCD reported elevated physical symptoms on both stress and non-stress days.

These findings are inconsistent with Neupert et al.'s (2007) research showing no age differences in reactivity to home stressors as well as theorists who argue that age differences in reactivity to home stressors reflect age differences in home-work spillover and home demands (Grzywacz et al., 2002; Serido et al., 2004). Rather, our findings suggest that SCD influences age differences in reactivity to home stressors. Although having high SCD appears to be equally detrimental across adulthood in terms of home stressors, having low SCD is only associated with resilience among older adults. Researchers have argued that individuals with a coherent self-concept respond to life events in more adaptive ways (Markus & Wurf, 1987; Showers et al., 1998; Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007). Research has also shown age differences in coping strategies whereby older adults favor more intrapersonal, emotion-focused ways of coping (Folkman et al., 1987). It is possible that both age and having a coherent self-concept may contribute to having a response style that is particularly adaptive to home stressors, and their combined effect may underlie the resilience that older adults with low SCD have to home stressors.

Network stressors

Consistent with Almeida et al. (2002), network stressors were associated with increased physical and psychological distress. Contrary to our expectations and research by Neupert et al. (2007), we did not find that age or perceived control buffered psychological reactivity to network stressors. Perhaps because network stressors happen to other individuals, adults' full repertoires of coping strategies and their own perceptions and characteristics (e.g., perceived control, SCD) are less able to mitigate the distress arising from such stressors.

In contrast, physical reactivity to network stressors was moderated by SCD and perceived control. Irrespective of perceptions of control, in adults with low SCD, network stressors were not associated with increased physical symptoms. In contrast, in adults with high SCD, network stressors were associated with increased physical symptoms on low control days, whereas they were associated with decreased physical symptoms on high control days. This latter finding was unexpected and might be an extreme example of how adults with high SCD are more sensitive to their perceptions of control than adults with low SCD. That is, adults with high SCD may be so sensitive to their perceptions of control that when they feel in control, stressors are seen as positive challenges or opportunities to exert control. Given that we only observe this finding for network stressors, however, the fact that the stressor occurs to another person may be important. Perhaps when adults with high SCD perceive heightened control they benefit from making comparisons with social partners who are under stress. We are not able to test such possibilities with these data. Nonetheless, research indicates that there are individual differences in whether individuals benefit from making social comparisons and that perceptions of control influence this process (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1993; Michinov, 2001).

Health stressors

Consistent with Almeida et al. (2002), health stressors were associated with psychological distress and physical symptoms. Regarding psychological reactivity, among adults with high SCD, health stressors were associated with increased distress irrespective of control. Among adults with low SCD, health stressors were associated with increased psychological distress on low control days. Possessing only one risk factor (i.e., high SCD or low daily control), therefore, is sufficient to increase adults' psychological reactivity to health stressors. This finding underscores the powerful nature of health stressors and the need for health care professionals to be sensitive to the relatively high vulnerability adults have to health stressors.

Regarding physical reactivity, despite older adults experiencing more health stressors than younger adults, younger adults were more physically reactive to them than older adults. As discussed above, older adults may perceive a certain degree of health stress as normative (Piazza et al., 2007; Leventhal & Crouch, 1997). Older adults may also have greater flexibility in their daily lives to accommodate health challenges (Piazza et al.). Alternatively, age differences in reactivity to health stressors could reflect age differences in the types of health stressors adults encounter. Notably, younger adults are more likely to have accidents (National Safety Council, 2006), whereas older adults are more likely to have chronic health problems (Jette, 1996; Manton, 1997; Wolff et al., 2002).

General Conclusions

Overall, our findings are consistent with the general perspective that being younger, having a more incoherent self-concept (i.e., high SCD), and perceiving less control, is associated with heightened reactivity to stress. Our findings do not support the idea that differentiated self-concepts are adaptive (e.g., Linville, 1987) and confirm that age is not systematically associated with heightened or decreased reactivity to daily stress. Rather, age differences in stress reactivity are complex and need to be considered in combination with other potential moderators such as SCD and perceived control.

Clinical implications

Psychosocial interventions have, for example, attempted to enhance adults' coping skills (e.g., Oxman, Hegel, Hull, & Dietrich, 2008), explanatory styles (Seligman, Schulman, & Tryon, 2007) and perceptions of control (Rodin, 1989). Our findings underscore the importance for such interventions to consider how risk factors interact to better identify adults who are particularly vulnerable to stress and who might benefit most from intervention. For instance, our results suggest that control-enhancing interventions would be most effective for younger adults (who are physically reactive to low perceived control even in the absence of stress) and for adults with high SCD.

Interventions should also build resilience in multiple ways to reduce reactivity to a spectrum of stressors. To our knowledge, no interventions have attempted to decrease adults' self-concept incoherence directly. Nonetheless, recent developments in cognitive behavioral therapy (Beck, Freeman, & Davis, 2003) and well-being therapy (Fava & Ruini, 2003; Ruini & Fava, 2009) point to possible methods of intervention. For example, Fava and Ruini (2003) used daily diaries to teach adults with depression how to recognize and cherish positive episodes in their lives. Such skills, in turn, have been shown to foster adults' self-reflection and self-acceptance in positive and enduring ways (Fava et al., 2004). It seems plausible that similar approaches could be beneficial for individuals with high SCD.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its strengths, this study has limitations. One limitation is due to sampling. The protocol was demanding and adults who withdrew from the study were younger and reported poorer well-being. We also had to oversample middle-aged men. As a result, the young adults in this study may be relatively high functioning and the middle-aged men may be more open to research than their same-aged counterparts. The sample is also predominantly Caucasian and some research suggests that possessing disadvantaged social statuses (e.g., being a racial/ethnic minority) is associated with increased exposure to stress (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008). This study may, therefore, underestimate the role of age and other factors in stress reactivity.

Perceptions of control may also vary in response to stress. Nonetheless, numerous studies suggest that perceptions of control precede and influence stress reactivity (e.g., Hahn, 2000; Neupert et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2005) and we found that approximately 70% of the variation in daily perceptions of control was between-person. Therefore, although perceptions of control vary, they also show considerable between-person stability. Consequently, the association between daily perceptions of control and stress is likely to occur, at least in part, in the hypothesized direction.

Finally, limitations may exist in the assessment of SCD. Participants are given some leeway when completing the measure. For instance, they are asked to describe themselves “with family” but are not instructed what specific family relationships to consider. Some of the between-person variation in SCD scores may reflect this imprecision. We would argue, however, that this shortcoming is not major because participants' individual ratings within roles are not compared. Rather, we use each individual's set of ratings to determine how similarly they describe themselves across these common roles. In addition, time constraints prevented us from assessing SCD on a daily basis and considering its role as a daily covariate of stress reactivity. Elsewhere we found that adults were more reactive to daily stressors on days they endorsed negative self-attributes more strongly (Diehl & Hay, 2007) and SCD is positively associated with how frequently adults endorse such daily negative self-attributes (Diehl, 2009). Developing a procedure to assess SCD in a more context specific way may, therefore, help elucidate how SCD influences stress reactivity.

Despite these limitations, this study offers insights for future research. The findings support the assertions of Ensel and Lin (2000) and other researchers (e.g., Almeida et al., 2002) that both physical and psychological outcomes should be considered in stress research. Research should also examine multiple types of stressors as they may be associated with different outcomes. For instance, Bolger and Schilling (1991) found interpersonal stressors were strongly associated with psychological well-being and our data suggest health and network stressors are particularly relevant for physical symptoms.

Research should also consider daily control in more detail. Such perceptions are closely tied to stress reactivity and, as Ong et al. (2005) note, fast-varying predictors may be particularly powerful predictors of fast-varying outcomes such as daily emotions. Finally, research should continue to examine how self-concept related variables such as SCD influence the daily stress process. Given that age interacted with SCD to influence stress reactivity, future research in this area may help explain mixed findings regarding age differences in stress reactivity.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this article was supported by grant R01 AG21147 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/pag

Linville's (1987) definition of self-complexity includes both the number and distinctness of self-aspects. Research in our laboratory has shown that the index of distinctness correlates very highly with our index of SCD and, hence, can be considered a measure of differentiation.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Horn MC. Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Chandler A. Daily spillover between marital and parent child conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The Daily Inventory of Stressful Experiences (DISE): An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. The effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:708–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler M, Neimeyer GJ, Brown E. The divided self revisited: Effects of self-concept clarity and self-concept differentiation on psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:396–415. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, Almeida DM. Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: A daily diary study. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:330–340. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. Ego-identity, role variability, and adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1961;25:392–397. doi: 10.1037/h0042979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:808–818. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Schilling E. Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:355–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollini AM, Walker EF, Hamann S, Kestler L. The influence of perceived control and locus of control on the cortisol and subjective response to stress. Biological Psychology. 2004;67:245–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Greve W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review. 1994;14:52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstädter J, Rothermund K. Self-percepts of control in middle and later adulthood: Buffering losses by rescaling goals. Psychology and Aging. 1994;9:265–273. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Krause N. Negative life events and age-related decline in mastery: Are older adults more vulnerable to the control-eroding effect of stress? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2008;63B:S162–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.3.s162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA, Mather M. Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation, and emotion. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6th ed. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2006. pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MC, Preveza E, Papandreou K, Prevezas N. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder following spinal cord injury and locus of control. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. NEO PI-R: Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yip T, Bolger N. A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:917–929. doi: 10.1177/0146167206287721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M. Association between SCD and endorsement of daily self-attributes. Unpublished raw data. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hastings CT, Stanton JM. Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:643–654. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hay EL. Contextualized self-representations in adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:1255–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hay EL. Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: The role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. 2009a. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hay EL. Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood among men with prostate cancer and women with breast cancer. Manuscript in preparation. 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Youngblade LM, Hay EL, Chui H. The development of self-representations across the lifespan. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Antonucci TC, Smith J, editors. Handbook of lifespan psychology. Springer Publishing; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue EM, Robins RW, Roberts BW, John OP. The divided self: Concurrent and longitudinal effects of psychological adjustment and social roles on self-concept differentiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:834–846. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizenman DR, Nesselroade JR, Featherman DL, Rowe JW. Intraindividual variability in perceived control in an older sample: The MacArthur Successful Aging Studies. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:489–502. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM, Lin N. Age, the stress process, and physical distress: The role of distal stressors. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:139–168. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans O, Steptoe A. The contribution of gender-role orientation, work factors and home stressors to psychological well-being and sickness in male- and female-dominated occupational groups. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:481–492. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C. Development and characteristics of a well-being enhancing psychotherapeutic strategy: Well-being therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34:45–63. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1872–1876. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Gatz M, Pederson NL. Depressive symptoms and aging: The effects of illness and non-health related events. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003;58B:P320–P328. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.p320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Pimley S, Novacek J. Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging. 1987;2:171–184. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Smith J. Content and function of the self-definition in old and very old age. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1999;54B:P55–P67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ. The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. Basic Books; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Greve W, Wentura D. Immunizing the self: Self-concept stabilization through reality-adaptive self-definitions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:39–50. doi: 10.1177/0146167202238370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Almeida DM, Neupert SD, Ettner SL. Socioeconomic status and health: A micro-level analysis of exposure and vulnerability to daily stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn SE. The effects of locus of control on daily exposure, coping and reactivity to work interpersonal stressors: A diary study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:729–748. [Google Scholar]

- Hay EL, Fingerman KL. Age differences in perceptions of control in social relationships. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60:53–75. doi: 10.2190/KQRF-J614-0CEQ-H32L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. The “self digest”: Self-knowledge serving self-regulatory functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:1062–1083. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jette AM. Disability trends and transitions. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 4th ed. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1996. pp. 94–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kling KC, Ryff CD, Essex MJ. Adaptive changes in the self-concept during a life transition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:981–990. doi: 10.1177/0146167297239008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J. Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Firth KMP. The adaptive value of feeling in control during midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 320–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. Sociodemographic variations in the sense of control by domain: Findings from the MacArthur studies of midlife. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:553–562. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M. Day-to-day physical symptoms: Individual differences in the occurrence, duration, and emotional concomitants of minor daily illnesses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:387–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal EA, Crouch M. Are there differences in perceptions of illness across the lifespan? In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of health and illness: Current research and applications. Harwood; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 1997. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Linville PW. Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:663–676. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG. Chronic morbidity and disability in the U.S. elderly populations: Recent trends and population implications. In: Mostofsky DI, Lomranz J, editors. Handbook of pain and aging. The Plenum series in adult development and aging. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Herzog RA. The role of the self-concept in aging. In: Schaie KW, editor. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. Vol. 11. Springer Publishing; New York: 1991. pp. 110–143. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Wurf E. The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 1987;38:299–337. [Google Scholar]

- Michinov N. When downward comparison produces negative affect: Sense of control as a moderator. Social Behavior and Personality. 2001;29:427–444. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell AR, Strain LM, Brown CM, Rydell RJ. The simple life: On the benefits of low self-complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:823–835. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Almeida DM. The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:355–378. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Safety Council . Injury facts (2005–2006 Edition) Author; Itasca, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2007;62B:P216–P225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi J, Pulliainen H, Salmelo-Aro K. Age differences in adults' control beliefs related to life goals and concerns. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:194. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Allaire JC. Cardiovascular intraindividual variability in later life: The influence of social connectedness and positive emotions. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:476–485. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. Unique effects of daily perceived control on anxiety symptomatology during conjugal bereavement. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:1057–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Oxman TE, Hegel MT, Hull JG, Dietrich AJ. Problem-solving treatment and coping styles in primary care for minor depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:933–943. doi: 10.1037/a0012617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza JR, Charles ST, Almeida DM. Living with chronic health conditions: Age differences in affective well-being. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2007;62B:P313–P321. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ. Simple intercepts, simple slopes, and regions of significance in HLM 3-way interactions [web-based software and manual] 2006 Retrieved from http://www.people.ku.edu/~preacher/interact/hlm3.htm.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rafaeli-Mor E, Steinberg J. Self-Complexity and well-being: A review and research synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J. Sense of control: Potentials for intervention. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1989;503:29–42. doi: 10.1177/0002716289503001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, Timko C. Sense of control, aging, and health. In: Ory MG, Abeles RP, Lipman PD, editors. Aging, health, and behavior. Sage; CA: 1992. pp. 174–206. [Google Scholar]