Abstract

Aging appears to be associated with a growing preference for positive over negative information (Carstensen, Mikels, & Mather, 2006). In this study, we investigated potential awareness of the phenomenon by asking older people to recollect material from the perspective of a younger person. Younger and older participants listened to stories about 25 and 75-year-old protagonists, and then were asked to retell the stories from the perspective of the protagonists. Older adults used relatively more positive than negative words when retelling from the perspective of a 75 versus 25-year-old. Younger adults, however, used comparable numbers of positive and negative words regardless of perspective. These findings contribute to a growing literature that points to developmental gains in the emotion domain.

Keywords: aging, positivity effect, perspective taking

“One thing about getting old is that you never lose the ages you’ve been.”

-Madeline L’Engle

Empirical research suggests that a preference for positive emotional information may emerge with age (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Issacowitz, Wadlinger, Goren, & Wilson, 2006; Kennedy, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mather & Carstensen, 2004; Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, & Cartensen, 2005; Schlagman, Schulz, & Kvavilashvili, 2006). This preference stands in contrast to findings from research that suggests that negative stimuli hold special attention-grabbing properties in younger adults (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Cacioppo, Gardner, & Berntson, 1997; see also Wood & Kisley, 2006). This developmental shift has recently been coined the “positivity effect” and has been observed in autobiographical memory, long-term memory, working memory, and attention (for review see Carstensen, Mikels, & Mather, 2006). Although the phenomenon is evident in multiple domains, little is known about the causes of the shift. Does the shift reflect developmental changes rooted in motivation? Or could it be the serendipitous result of neural or cognitive decline? In this paper we explore whether older adults display an implicit awareness of an age-related preference for positive over negative information.

To address this question, in the present study we asked younger and older adults to recollect a day in the life of a person told from the perspective of a younger or older protagonist. We reasoned that if people have some degree of awareness of a developmental trajectory of change, they may display positivity in their retellings from the perspective of an older main character while less so in their retellings from the perspective of a young main character. Grounded on the axiom that whereas all older adults were once young, younger adults have never been old, we hypothesized that older adults would modify their retellings according to the main character’s age and younger adults would not.

There has been little prior research on perspective taking in the elderly, and extant research has focused largely on tasks that require significant cognitive resources (Chasseigne, Lafon, & Mullet, 2002; Ligneau-Hervé & Mullet, 2005; Pratt, Diessner, Pratt, Hunsberger & Pancer, 1996). Many of these studies suggest that certain perspective-taking abilities decline with age. Yet, other studies suggest that older adults may have an advantage relative to younger adults when perspective taking relies less on cognitive capacity and more on life experience, as older adult self-reports indicate (Martini, Grusec, & Bernardini, 2001). On tests of dialectical reasoning, for example, or the predilection to acknowledge and reconcile opposing perspectives, older adults’ performance is commensurate or superior relative to younger adults’ performance (Blanchard-Fields, 1989; Pratt et al., 1996). Thus, perspective-taking abilities do not necessarily decline uniformly across the life span.

The task in the current study was designed to measure perspective taking in a manner consistent with the motivational frame of older adults. Each additional year of life that individuals live offers opportunity for them to gain experience, whether in the form of education, parenthood, provision of mentorship, or understanding of other people. Baltes and Staudinger (2000) maintain that these experiences in everyday life may facilitate the development of wisdom. While research to date suggests that wisdom is maintained across the adult life span (e.g., Staudinger, 1999), affective perspective taking might be one wisdom-related domain in which there are increases over the course of development as it is a phenomenon that is theoretically wedded to a developmental process (viz., a shift in motivation associated with an increasing perception of constraints on time left in life). As Madeline L’Engle aptly observed, older adults have known what it means to be a younger adult. Indeed, according to Baltes and Staudinger (2000), wisdom comprises “knowledge about the condition, variability, ontogenetic changes, and historicity of life development as well as knowledge of life’s obligations and life goals” (p.124). Because increasing age may be related to the acquisition of wisdom-related concepts about life development (Baltes, Staudinger, & Maercker, 1995; Gluck & Baltes, 2006), it is conceivable that older adults have some degree of awareness of ontogenetic changes, which may include the positivity effect. If so, they may be better able to take the affective perspectives of younger people than younger people are able to adopt the perspectives of older adults.

In the current study, we employed a perspective-taking paradigm in which participants were asked to retell recorded stories containing events described in emotional language from the perspective of a young main character and from the perspective of an old main character. We predicted that across all conditions older adults would use more positive relative to negative words in comparison to younger adults. Furthermore we hypothesized that older adults would use more positive relative to negative words when retelling a story about an older adult than when retelling the story about a younger adult, whereas younger adults would show no valence effect as a function of main character age.

Method

Participants

Twenty older adults and 20 younger adults were paid $25.00 to participate in the study. All participants resided in the San Francisco Bay area, were community dwelling, and were not suffering from any major neurological or psychiatric illnesses. Participants were recruited through postings on the online message board Craigslist and from a name bank in the Life-span Development Laboratory at Stanford University. The name bank contains contact information from people who have indicated an interest in participating in studies in our laboratory. Older participants (64–88 years of age, M = 75.44, SD = 6.88) were 50% female and included 4 African Americans and 12 European Americans. Younger participants (18–29 years of age, M = 22.72, SD = 3.27) were 44% female and included 5 African Americans and 13 European Americans. No significant differences between the two groups were found in years of education (Younger: M = 14.56, SD = 1.79; Older: M = 15.56, SD = 2.68, t(32) = 1.22, p > .2), scaled income (Younger: M = $47,200, SD = $32,900; Older: M = $66,000, SD = $42,100, t(31) = 1.44, p > .1), or self-rated health (Younger: M = 2.00, SD = 0.91; Older: M = 2.31, SD = 0.95, t(32) = .98, p > .3).1 Consistent with the literature, the older adult group performed more poorly on the measures of speed of processing, Digit-Symbol Coding (Younger: M = 80.33, SD = 22.23; Older: M = 55.87, SD = 15.64, t(31) = 3.58, p < .001), and short-term memory, Digit Span (Younger: M = 19.67, SD = 5.42; Older: M = 14.13, SD = 3.83, t(32) = 3.40, p < .005), but comparably well to the younger adults on a test of knowledge, Vocabulary (Younger: M = 45.89, SD = 10.53; Older: M = 41.56, SD = 11.32, t(32) = 1.16, p > .2).2

Materials

A computer equipped with iTunes software was used to present audio-taped recordings of stories. Participant responses were recorded using a standard tape recorder placed next to the computer. In addition to completing the main study task, participants also completed a consent form, a demographic information form, and measures to assess physical health and cognitive functioning.

Perspective Taking Stories

Two stories were written in the third person and audio recorded for this task. For purposes of experimental control, the same narrator (a younger female adult) was used in all recordings. Importantly, the stories were created in consultation with both male and female younger and older adults such that the main character in each story could believably be a 25-year-old or 75-year-old man or woman. To that end, the stories were about events that took place over the course of a weekend and that would be likely occurrences in the life of an older or younger adult. Male and female versions of each story, which varied only the gender of the main character, were constructed and the gender of the main character was matched to the gender of the participant. Stories contained six negative and six positive events. (See online supplement Appendix A for full text of the two stories.)

Experimental Design & Procedures

Following completion of the consent form and demographic information form, participants were told that they would listen to two stories, one about a character 25 years of age and one about a character 75 years of age, and that after each story they would be asked to reflect aloud on the weekend from the perspective of the main character. Each participant listened to both Story A and Story B, and the order in which Story A and Story B were presented was counterbalanced across participants. To control for specific item effects, whether Story A or Story B featured a young or old protagonist was counterbalanced such that across participants each story was presented featuring a young and old protagonist an equal number of times. Before listening to each story, participants heard:

“The [first/second] story is about [Name of protagonist – gender matched to participant] who is [25/75] years old. After listening to the story, you will be asked to reflect aloud on the weekend from [Name of protagonist]’s perspective, recalling those events that you think would be most important to [Name of protagonist].”

After each story, the participant was given three minutes in which to reflect aloud on the day. Upon conclusion of the second reflection period, the experimenter returned to the room and administered the Wechsler Digit Span, Wechsler Digit-Symbol, Wechsler Vocabulary, and Self-Rated Health form.

Results

Data Reduction

Audio-taped responses were transcribed and then coded using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) system developed by Pennebaker and Francis (1994). The LIWC system is a computer program that can be used to score written text on several dimensions, including valence. The LIWC dictionary includes 261 positive and 345 negative emotion words, which the program recognizes and uses to compute percentage scores of positive and negative emotion words used. One participant was excluded from all analyses due to a tape-recorder malfunction. Data from five outliers (2 younger and 3 older participants) were excluded because the frequency of positive and/or negative words used in reflections fell more than two standard deviations outside of the of the respective group mean for that frequency.

Because stories contained six positive events and six negative events, differences in memory for these events could confound the perspective-taking measure. Therefore, we were prompted post-hoc to rule out the possibility that any differences in the valence of older and younger adult reflections could be explained by event salience. Two independent raters blind to participant age scored responses for the number of positive and negative events mentioned in older and younger reflections. Agreement between raters was 74% (κ = .70). The following recall results hold regardless of which rater’s scores are used in the analysis, so the scores of only one rater are reported below.

Perspective Taking Analyses

In order to operationalize perspective taking in the current experimental context, we employed the following rationale: Given that older adults are typically more positive and less negative in comparison to younger adults, when an individual takes the perspective of an older adult they should use more positive and less negative language than when taking the perspective of a younger adult. Thus, to assess perspective-taking performance in this context we used the percentage scores for positive and negative emotion words output by LIWC (see online supplement Appendix B for example reflections). Separate analyses considered the percentage of positive and negative words used (the primary dependent variable) and the number of positive and negative events mentioned (to rule out the possibility that the valence of participant reflections represented a bias in memory for either positive or negative events as opposed to a bias in the appraisal of events).

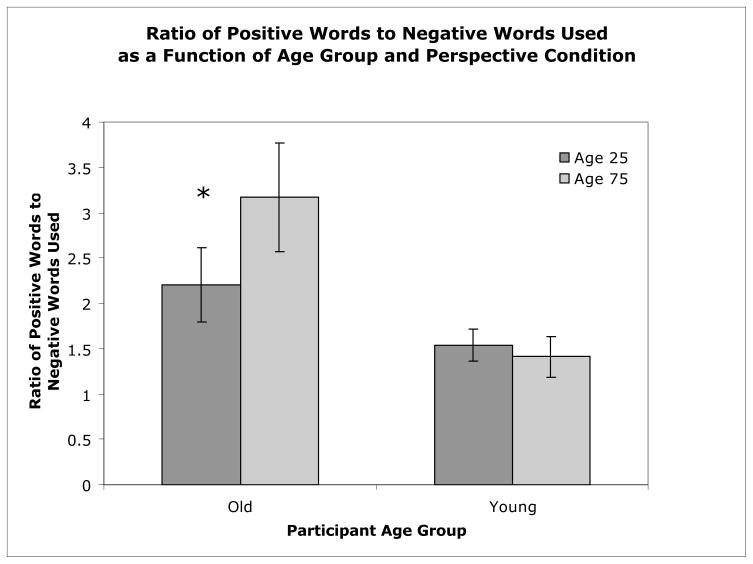

Data were submitted to a repeated measures ANOVA with the between subjects factor of age group (young, old) as well as with the two within subject factors of main character age (25 years, 75 years) and valence (positive, negative). A significant main effect of valence was found, F(1,32) = 20.88, p < .001, ηp2 = .40. Across conditions participants used more positive words (M = 1.98%, SD = 0.62) than negative words (M = 1.34%, SD = 0.61). A valence by group interaction was also significant, F(1,32) = 5.39, p < .05, ηp2 = .14. Overall, older adults used more positive words (M = 2.16%, SD = 0.71) and fewer negative words (M = 1.17%, SD = 0.61) relative to younger adults (positive: M = 1.82%, SD = 0.50; negative: M = 1.50%, SD = 0.58). Most importantly, a three-way interaction of valence by group by main character age emerged, F(1,32) = 6.52, p < .05, ηp2 = .17 (see Table 1). When retelling a story from the perspective of a 75-year-old, older participants used more positive and less negative language than when retelling a story from the perspective of a 25-year-old. Younger adults did not show this pattern. These results are shown in Figure 1 (for purposes of graphical clarity the figure presents the ratio of positive to negative words used). 3 No other significant effects were found.

Table 1.

Frequency of positive and negative words used broken down by group and main character age

| Group | Main Character Age | Positive | Negative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (%) | (SD) | M (%) | (SD) | ||

| Young | |||||

| 25 years* | 2.00 | (0.66) | 1.51 | (0.69) | |

| 75 years | 1.65† | (0.64) | 1.49‡ | (0.77) | |

| Old | |||||

| 25 years* | 2.00 | (0.97) | 1.32 | (0.78) | |

| 75 years** | 2.31† | (1.04) | 1.02‡ | (0.73) | |

Note. Between-subject effect:

indicates a significant difference at p < .05;

indicates a difference at p < .08.

p < .05

p < .001

Figure 1.

Ratio of positive words to negative words used. Results are shown separately by perspective condition (main character age: 25 & 75) for older adults and younger adults. Error bars display the standard error of the mean.

Post-hoc Analyses

To test for possible memory effects, we calculated the total number of the six positive and six negative events mentioned in reflections by each participant for both the 25-year-old and 75-year-old perspectives. The data were submitted to a repeated measures ANOVA with the between subjects factor of age group (young, old) and the two within subjects factors of main character age (25 years old, 75 years old) and valence (positive, negative). There was a significant effect of valence, F(1,32) = 52.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .62. All participants recalled more negative (M = 6.62, SD = 2.15) than positive events (M = 4.03, SD = 2.19). The analysis also revealed a main effect of age group, F(1,32) = 11.57, p < .005, ηp2 = .27. Younger adults recalled significantly more events than older adults (M = 12.44, SD = 2.97; M = 8.63, SD = 3.58, respectively).

To rule out the possibility that more negative events were recalled because the specific negative events included in the stories were more arousing than the specific positive events, we analyzed the specific negative and positive events for perceived differences in valence and arousal. We asked a group of 29 younger adults to provide arousal ratings for the specific events contained in the stories and found no differences in mean arousal (Story 1: t(5) = 0.24, p > .05; Story 2: t(5) = 0.90, p > .05) for positive in comparison to negative events, nor any differences in mean positive event arousal (t(10) = 0.52, p > .05) or negative event arousal (t(10) = −0.57, p > .05) between the two stories.4

Discussion

The current study investigated whether there exists an age-related positivity effect in the retelling of stories containing daily life events, and whether older and/or younger adult retellings reflect this differential positivity. We assessed positivity in an affective perspective-taking task, which was in turn evaluated as the relative proportion of positive and negative words used by participants when taking the perspective of a 75 versus a 25-year-old. We hypothesized 1) that across conditions older adults would use more positive relative to negative words in comparison to younger adults, and 2) that older adults would use more positive relative to negative words when taking the perspective of a 75-year-old as opposed to a 25-year-old but that younger adults would not. The pattern of results supports this hypothesis. In contrast to documented declines in perspective-taking ability involving non-emotional information, affective perspective taking may represent a domain in which older adults demonstrate superior performance relative to younger adults. Moreover, the differential retelling of the day according to the age of the person whose perspective was being taken suggests that older adults are at some level aware of the age-related positivity effect. We recognize that the term “aware” is imperfect as our data provide no insights into the reasons for this pattern of findings. However, the fact that older people show a recollection pattern that reflects the positivity effect whereas younger adults do not – even when the stories were matched in all other ways – suggests some appreciation that there are age differences in positivity.

Furthermore, if older adults are indeed capable of assuming the less positively biased perspective of a younger person it is unlikely that the positivity effect is the serendipitous consequence of cognitive decline and the inability to process negative emotional information as well as positive. Wurm, Labouvie-Vief, Aycock, Rebucal, and Koch (2004) have suggested that older adults “reduce the complexity of affective information, distorting it in a positive direction” (p. 523). However, results of the current study support the viewpoint that older adults are able to process and encode negative information. The present results further suggest that older adults are aware that their younger counterparts do not display this selectivity. Rather than distorting affective information, older adults in this context appear to represent it with a sensitivity to age perspectives that younger adults do not possess. Furthermore, in the current study older adults, like younger adults, remembered significantly more negative events than positive events regardless of the perspective they were taking. The specific event data indicate that for older adults the perspective taking manipulation did not influence the type of information that was retrieved but rather how that information was appraised. Both younger and older adults recalled more negative events but used more positive relative to negative words in their reflections on the story as a whole.

Older adults observed in this study, were not blind to negative events; rather they put the best “face” on them. This finding contributes to the nuanced pattern of empirical findings about the positivity effect that is emerging in the literature – findings that are highly consistent with a motivational account. As theoretically defined, the positivity effect reflects the age-related motivation to maintain emotional wellbeing. Attention to positive is the chronically activated default. However, when experimental instructions require older participants to process negative stimuli, the positivity effect is not observed (Rosler et al., 2005; Samanez-Larkin, Robertson, Mikels, Carstensen, & Gotlib, in press). When older adults are explicitly asked to be as accurate as possible the effect is eliminated (Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2007). When cognitive load increases or when the task requires the processing of both positive and negative stimuli, the effect disappears (for reviews, see Kryla-Lighthall & Mather, 2008; Mather & Carstensen, 2005). Such findings speak against rival explanations for the positivity effect, such as cognitive decline or neural degradation, and contribute to an emerging picture of an adaptive, motivated shift in attention.

In the current study, we were interested in investigating the overall tone of younger and older adult reflections. Consistent with positivity in appraisal of daily activities, older adults used more positive words across both the 25-year-old and 75-year-old perspectives than did younger adults, and especially so when recalling from the perspective of an older person. This pattern of findings provides support for the argument that older adults have some awareness that the perspective of an older adult is likely to be more positive than that of a younger adult. Alternatively, it is also possible that these findings reflect that positivity is partially moderated by perceived similarity to the protagonist (i.e., older adults do not know that younger adults are less positive but rather are compelled to apply positivity more strongly to individuals whom they perceive to be more similar to themselves).5 Future perspective-taking research that manipulates additional characteristics of story protagonists, such as ethnicity or gender, will be required to rule out this interpretation of the data.

Most importantly, only older adults differed by experimental condition in accordance with the age-related positivity effect observed in this study as well as others. This interaction suggests that while the verbal responses of older adults may reflect some degree of knowledge of the positivity effect those of younger adults do not. These findings contribute to models of wisdom by suggesting that older adults are aware of ontogenetic changes, such as shifts in motivation, that have taken place over the course of their lives (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000). Although consistent age differences in wisdom have yet to emerge, the current study indicates that further analysis of discrete, theoretically wisdom-related skills, such as affective perspective taking, offers a potentially promising direction for investigation. We expect that Madeline L’Engle would be pleased to know that insight into developmental trends in affective preferences may be a component of wisdom that emerges with age.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hal Ersner-Hershfield, Katharina Kirchanski, and Greg Larkin for their assistance in both intellectual and practical matters. We also wish to acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Fairchild, Kevin Hoyle, Sam Maglio and the entire Lifespan Development Laboratory at Stanford University. The basis for this paper was the first author’s honors thesis at Stanford, and the findings were presented during a poster session at the 2006 Annual Convention of the Association for Psychological Science held in New York City. This project was supported by National Institute on Aging research grants RO1-AG08816 to LLC and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award AG022264 to JAM.

Appendix A

Story A (Please note that for male participants the name of the main character was changed to David.)

On Friday afternoon Anna decided to make herself a cup of coffee and read the newspaper. She read articles about the upcoming elections, the dog show that would take place that weekend, and the town’s high school musical that would be opening the following weekend. Her reading was interrupted when the phone rang. Answering the phone, Anna expected the caller to be someone trying to sell her carpet cleaner or dog shampoo, but was pleased when she heard the familiar voice of a friend from whom she had not heard in several years on the other end of the line. The two chatted for an hour and a half, recounting good times they had shared together and catching up on each others’ lives. After saying good-bye to her friend, Anna decided to begin preparing dinner for herself.

Since she was planning to go to a potluck the following day, Anna decided to prepare two dishes of lasagna: one lasagna that she would have some of for dinner and another lasagna that she would take to the potluck. She had just finished chopping the vegetables and soaking the noodles when she went to the cupboard and realized that she had run out of tomato sauce and forgotten to pick some up at the store the day before. This was very frustrating because she had tried to be very careful about making a complete shopping list so that she wouldn’t have to go back to the store for another week, but now she was forced to head out to the store on a Friday evening.

Disgruntled and a little fatigued, Anna put on her jacket, hat, and gloves and headed off to the supermarket. After pulling into the parking lot, Anna headed to the entrance of the store and picked up a shopping basket on her way to the canned goods aisle. She scanned the shelves for her favorite brand and picked up four cans of it so that she’d have tomato sauce waiting on her shelf the next time that she wanted to make lasagna. The produce section happened to be right next to the canned goods and Anna noticed that her favorite food in the world, mangos, happened to be on sale. Anna loved mangos, but typically their high price prevented her from buying them very often, but they were such a good price that evening that Anna decided to buy three.

After selecting her mangos, Anna got in line at the checkout and paid the cashier. While driving back home, she went over the rest of her plans for the weekend. “Was Sunday the 17th or the 18th of the month?” she wondered to herself. “Oh no! wait!” she thought to herself, “Sunday must be the 18th because the potluck is tomorrow and the potluck is on the 17th, but that means that today must be 16th which means that yesterday was Frank’s birthday and I didn’t send a card or call.” Frank had been a very good friend of Anna’s for a long time. Every year he always remembered her birthday but it seemed that every year his birthday managed to slip her mind. “Why can’t I just remember his birthday?” she thought as she grew embarrassed and disgusted with herself. She would have to send a card and take him out to lunch sometime soon to make up for forgetting his birthday and she was angry about that. When Anna arrived home, she finished putting together the lasagna and popped it in the oven. After watching a bit of TV, she sliced her bread and spooned her piping hot lasagna onto a plate. After dinner, she made herself another cup of decaf coffee and petted her cat Chester while watching the news. When she started yawning she got ready for bed, turned out the lights, and fell asleep.

The next morning, Anna got up and decided to go for a walk in the crisp autumn sunlight. Out on her walk, Anna walked through the main streets of the sleeping town and then out into the residential area on the opposite side of the town from where she lived. Just as she was turning around back toward her side of town, she felt something under her foot squish and slide just a bit. Looking down at the ground, Anna was disgusted to find that she had stepped in dog poop and that the foul material had managed to smear up into the pure white surface of her new tennis shoes and was repulsed by the smell. “Ug,” she thought to herself, “I wonder if I’ll be able to get all this gross stuff out of the canvas.” She cleaned the shoes as best she could in the grass of the parking strip and continued walking back to her apartment angry and disgusted.

The paperboy had just dropped off the Saturday paper when she arrived at her doorstep. He greeted her and they chatted about the weather for a few minutes before she unlocked her door and the paperboy went about finishing his route. Anna prepared herself breakfast and cleaned the dirty dishes left over from making lasagna, glancing every so often at the clues in the crossword puzzle that she liked to work on during the weekend. After finishing her breakfast, Anna continued work on her crossword puzzle and let Chester the cat sit in her lap as she puzzled over the clues.

At about one o’clock Anna decided to take a shower and run some errands. After she got dressed, Anna went to the drugstore, the dry cleaners, and the hardware store. Returning home she made a cup of coffee and sat down again with her crossword puzzle. At five o’clock, she smiled enthusiastically as she filled in the last square of her crossword puzzle. How deeply satisfying to finish the whole crossword puzzle without consulting with anyone else! She felt so proud of herself and so joyful to have completed the puzzle! She looked over at Chester who purred in agreement and then realized that she needed to get ready to go to the Larkin’s potluck. One of her friends, Rachel, was going to pick her up and then they would go to the potluck together. Neither Rachel nor Anna liked going to social gatherings by themselves, so they often went places together. However, just as Anna was pulling the lasagna out of the refrigerator, Rachel called to say that she wasn’t feeling well and didn’t think it would be a good idea for her to go to the potluck. Rachel apologized and Anna said not to worry, but Anna wasn’t really sure whether she wanted to go all by herself. She hung up the phone feeling very disappointed in Rachel and nervous about going to the party alone. The entire situation made Anna feel very sad. Chester came over and rubbed up against her legs. Anna sighed and glanced down at the large casserole dish full of lasagna and decided that she didn’t want to have to eat all that lasagna all by herself, so she decided to go to the potluck but was still very nervous.

Locking the door behind her, Anna got into her car and onto the interstate and she started to feel even more nervous and fearful. She didn’t like driving on the interstate and she wasn’t very good at following directions. She was driving in the right hand lane when she noticed that her exit was coming up on the left hand side of the freeway. “How am I going to get across two lanes of traffic?” she thought to herself. But miraculously, the drivers in the lanes next to her saw her signal and let her in just in time to make it to her exit. Anna breathed a sigh of relief as she waved in her rearview mirror to the thoughtful drivers. She felt content and pleased that people could be so thoughtful.

The Larkin’s greeted Anna at the door and asked her what she’d like to drink. They introduced her to a couple that was working on the school board and the three began talking about local politics as they filled their plates up at the buffet. They sat down and continued talking until Kathryn, one of Anna’s old friends, came over to say hello and the couple went over to the buffet for seconds. Kathryn leaned closer to Anna and said in a hushed tone: “You might want to take a trip to the restroom, you’ve got spinach all caught up in your teeth.” Anna turned bright red and went in search of a bathroom to clean out her teeth. She hated thinking about having talked to new people with a bunch of spinach wedged in her smile. She felt ashamed and embarrassed, wishing that she hadn’t come to the party in the first place.

Having successfully washed out her mouth, Anna left the bathroom and headed back to the buffet. On her way past the living room she overheard several people standing together talking about what fabulous lasagna they were eating. How tender and flavorful it was! Anna smiled to herself feeling so proud and joyful that her dish was being enjoyed and she scooped another serving of lasagna onto her plate. After chatting with friends for another hour or so, Anna decided to head home.

The next morning, Anna slept a little later than usual and woke up when Chester started meowing to be fed. She scratched his head and filled up his dish before popping some bread in the toaster for herself. With the cat happily munching on his breakfast, she went out to collect the morning paper. Her neighbor across the way had also just stepped out to get his paper and they discussed the weather before stepping back into their apartments. An unappealing smell met Anna’s nose as she returned to the kitchen: her forgotten toast remained burning in the toaster. As she couldn’t stand to waste food, Anna sighed and buttered the blackened toast before sitting down to read the newspaper. She ate the disgusting toast, feeling so angry about having burned it.

Later that afternoon, Anna cleaned the bathroom, did laundry, and a made a list of tasks to accomplish in the coming week. Just as she was finishing her list, the timer on the washer went off and she transferred her wet clothes to the dryer. As she was shutting the door to the dryer she noticed a light piece of cloth caught in the space between the dryer and washer. Retrieving the mysterious object, she was thrilled to find that it was her sock that had gone missing two weeks earlier. Its mate lay alone in her sock drawer and she chuckled so excited at the thought of their reunion.

Having eaten so much lasagna that weekend, Anna felt like eating something a little lighter for dinner and so prepared a salad and ate it while watching the evening news while Chester played with a catnip toy in front of the television. She read until bedtime and then drank a cup of tea, brushed her teeth, and turned out the lights.

Story B (Please note that for female participants the name of the main character was changed to Emma.)

Steve awoke Saturday morning and as usual, sat looking out at the street until his dog Ted’s scampering around the kitchen became too annoying to ignore. “Come here, Ted, let’s put your collar on and go for a walk.” Steve and Ted headed out to get some fresh air and pick up a loaf of bread at the bakery. On the way to the bakery, Steve decided to stop by his favorite coffee shop for a cup of coffee and his pastry. He hadn’t been there in a couple weeks because he’d been trying to lose weight and the pastries weren’t helping, but he thought that this Saturday was a good morning for a pastry. As he walked up to the counter one of the baristas cried out: “Steve! Where have you been? We were worried you’d found another favorite coffee shop!” “No, no,” Steve replied, “Just trying to lose a few pounds – glad to know that you missed me!” He was so happy to have friends in the coffee shop, it made him feel content and at home. He ordered a large coffee, a cinnamon role, and a pumpkin muffin for good measure, and headed out to buy his bread.

Steve had just stepped outside the coffee shop when he took a large sip of his coffee and nearly spat it out because it was so hot. His tongue tender and burned, Steve couldn’t enjoy his pastries as he normally would. In pain, he was angry that he’d so quickly drunk the coffee and now couldn’t enjoy his pastry. Steve and Ted continued several more blocks past the neighborhood school, a library, a stationary store, several clothing stores, and a fish market before arriving at the bakery that they went to every Saturday. The bakery was open seven days a week, but Steve only visited on Saturday because Saturdays were the only day that the baker made rye bread, Steve’s favorite. The warm smell of fresh bread greeted Steve as he opened the door, but he was surprised not to see any fresh loaves of rye bread lined up neatly on the display racks. “Has the rye not come out of the oven yet?” Steve asked the teenager working behind the counter. “Sorry, sir, we didn’t make rye this week because it hasn’t been selling very well.” “So do you think that you’ll start making it again in a couple weeks?” Steve inquired. “Well, I’d like to say so, but I don’t think that we will. We were only selling about three loaves a week. Can I get you a different kind of bread?” “No, no, that’s okay,” Steve said slowly, wondering where he would find another loaf of rye that he liked as much as he’d liked that rye. He was very sad and disappointed that he couldn’t get his bread.

When he got home, Steve finished his coffee and pastries, took out the trash, swept the kitchen floor, and took a shower. As he was settling down to his new book on black holes, Steve heard the mailman outside and rose from his chair to get the mail. He quickly sorted through the pile, throwing away the advertisements and tossing the bills on the kitchen table. At the bottom of the stack was a square little envelope addressed in familiar handwriting. “Why is Matt sending me a note?” thought Steve. Opening the envelope he found a short note thanking him for being a good friend and a photo of the two of them together. Steve smiled feeling so happy that he had such a wonderful friend, grabbed a magnet, put the photo up on the refrigerator, and placed the card on his desk. He felt proud displaying these gifts.

Reading his book for the rest of the afternoon, Steve was so caught up in learning about the mysteries of black holes, that he lost track of time and left a few minutes late for his weekly dinner with friends at a favorite Italian restaurant. Putting on his coat, he walked out to the subway station. After waiting a few minutes for a train, Steve climbed aboard a crowded train and had to stand for the first few stops. At the third stop, Steve was just about to sit down in a seat that had just been vacated, when a man dressed in a business suit who had just boarded the train darted into the seat that Steve was about to sit down in. The man looked at Steve and smiled sheepishly before hiding behind his newspaper. Steve was angry at this man and felt very disappointed that someone would do something inconsiderate like that. He remained standing for the rest of the trip.

Steve’s friends had been waiting for about half an hour when Steve arrived. “Where have you been?! We’re starving! Why are you always late?” “I’m really sorry I’m late. I lost track of time.” His friends looked skeptical. “You’ve been late every time we’ve gotten together in the past month. “I’m really sorry, I was reading a book and forgot the time.” “Well, let’s just order,” Jake said, looking annoyed. Steve felt so ashamed and disappointed in himself. Just then the waiter, looking impatient, arrived and asked to take everyone’s orders. Steve ordered tortellini and the four caught up on the events of the past week. “What did you do today, Steve?” asked Daniel. “I starting reading this great book about black holes – it’s fascinating. I had no idea that no one really knows what happens in a black hole,” said Steve. “Geez, Steve,” chuckled Jake, “I wish that I spent my time actually learning new stuff rather than just watching TV – not that I should really be surprised: you’ve always been the smart one of all of us.” Steve smiled inwardly thinking that it was nice that his friends appreciated one of his esoteric interests. He felt pleased and proud that his friends appreciated his intelligence.

After dessert, one of Steve’s friends mentioned that he was planning a vacation to Florida. Steve launched into a description of all the wildlife unique to the Florida keys and ten minutes later noticed that his friends were nodding off to sleep. Feeling embarrassed and sad to have bored his friends, he said goodbye and headed back down into the subway.

Sunday morning after drinking a cup of tea and walking Ted, Steve flipped on the TV to discover that a local station was showing an all day “I Love Lucy” marathon. “Fantastic!” thought Steve as he settled down on the couch with Ted at his feet. “This is way to spend a rainy Sunday.” After spending the day laughing along with Lucy feeling great amusement and joy from the program, Steve broiled some chicken for dinner and took Ted out for an evening walk because the rain had stopped. The sun was just setting as Steve climbed a hill near his apartment. Looking out to the west, Steve and Ted admired the purple and blue hues that clouded the horizon and felt such awe at the beautiful view.

There was a nip in the air when Steve returned home and he decided to take a hot shower. Two minutes after he stepped into the shower, the water turned cold and Steve was forced to step out shivering. He was very angry that the water heater still wasn’t fixed. The landlord was supposed to do it weeks ago. Steve dried off, climbed into bed, and promptly fell asleep.

Appendix B

Younger Participant Reflection from 25-Year-Old Perspective

Alright, so um, Steve’s weekend was a cool weekend. Um, the uh, let me see, when he was in the bakery, and uh no not the bakery, the the coffee shop, when all of his friends were like, “hey uhh where were you? We’d thought you had gone to another place.” He he felt good about uhh having friends. Um, and uh then later uhm he had a negative moment where he drank his coffee. It was too hot and then he couldn’t enjoy the pastries. Um, and then that followed by another negative moment with uhh uh the, you know, when he went to the bread store and they didn’t have any rye. So, he didn’t get any rye. Umm, and uh, excuse me, and then like um, let me see, uhh he went on the train - no that was later. Uhm, let’s see, he he went out with Ted. Damn, I don’t even remember. Oh, I guess the other important thing was when uh his friend said that he was smart, um, that was cool because he thought, he he liked that. Oh, when he was reading black holes. When he was reading about black holes? Um, he was getting excited because uh no one really knows what happens inside of a black hole. That’s important because, you know, he he was thinking about the world and the universe and things around him. And um, let me see, the the sunset, when he was looking at the sunset with the dog, uhh he thought that was pretty cool. Umm, yeah Steve seems like a nice guy. Um, if he’s twenty-five years old that probably means he went to college, considering he’s studying black holes. Um, and uh, so I guess, I don’t, I don’t know what kind of a job he has though. Umm, so yeah, I guess when when he went out with his friends, um he was pissed off on the train because the bunghole businessman showed up and got a, like sat down in a good seat. Um, but uh, he should have just stolen the businessman’s suitcase because that would have been pretty cool. Um, er, uhh, yeah, um, and, with with the rain. Oh yeah, I Love Lucy. He was laughing along with I Love Lucy. He liked that. That was fun. Uhm, but quite frankly he didn’t get anything done this weekend, aside from reading about black holes. That was useful. Um, he went out to dinner with his friends who were all pissed off at him, and uh, they got bored because he was talking about the Florida animals because he’s stupid. Um, he’s one of those uhh smart people that’s actually smart, but he’s not like socially smart because he doesn’t understand how to have friends. Um, yeah, Steve’s a little, Steve’s a lame guy. But, anyway, uhh, yeah, Iguess, Iguess that was, those were all the high and low points in Steve’s weekend that were important to him. Um, screen savor went on. Looks like the time is about to be up though.

Younger Participant Reflection from 75-Year-Old Perspective

Emma woke up Saturday morning and took her dog Aaron for a walk. They went by a bakery that she hasn’t been to in a while because she has been loosing weight, been trying to loose weight. And so, she was very happy to know that her friends had wondered why she hadn’t been there, but was happy to see them. And then, her and Aaron her dog decided they walked a little while further and she went into a bakery, another bakery that bakes rye bread that she enjoys, but this particular week they didn’t have any rye bread because it wasn’t selling well. They returned home and then she got a letter from her friend Elizabeth who sent her a picture saying how glad she was that they were friends. And, she put the picture on the refrigerator. She was very excited. She began to read a new book regarding black holes, and then while reading the book for while she had to get ready for a dinner party with some friends at a tiny restaurant and they meet every week. There was a very rude woman on the subway on the way there. And in turn, she was late for her dinner party about half an hour. She ordered tortellini. Her friends were not too happy that she was late. And, she started talking to another friend, something about a trip to Florida. All the friends were falling asleep and then she returned home for the evening. And Sunday, after drinking her tea, her and her dog Aaron went for a walk and then they went, I believe, for a nice hike. And, let’s see, she was reading her book some more, and she also was a little bit chilly. The hot water heater broke. Um. Hmm. She was very irritated that the hot water heater broke and then, let’s see, she hmm. There was a teenager in the bakery that told her about the rye bread. And she thought that. Oh, the I love Lucy marathon was on on Sunday. As it was raining on Sunday, she thought it was a good day to stay home watching I love Lucy, and that’s what she did. Umm, she turned in early for the night. That’s all I can think of that happened with Emma on her weekend.

Older Adult Reflection from 25-Year-Old Perspective

Anna was very excited about hearing from her girlfriend and uh invited uh her Anna to come to uh potluck. And um, she decided that it would be nice to make some lasagna, uh and as she was doing the lasagna, she noticed that she uh didn’t have the uh tomato stuff that she needed for the lasagna. So she was pretty disgusted that she had to go to the store, but I guess that there was no other way to do that, so off she went. And uh she also heard from uh, no she was thinking about a male friend of hers, she had forgotten his birthday so she would have to take him out for lunch sometime so uh she didn’t like that too much. But anyway she went to the store to get the tomato, canned tomato ‘ stuff for her lasagna, and um she uh got done and also noticed that mangos were on sale and she just loves mangos so she bought some of those and uh and she then went on her way. She stepped in some uh dog stuff and got pretty disgusted about that because she had uh her shoes were all nice and clean and she didn’t know if she could ever get that off again. So anyway she went xxxx clean it as good as she could and went on home. And uh did the lasagna and uh she was so tired that she fell asleep. So then the next day she uh, oh I can’t remember what she was doing but um. I guess uh that’s right her girlfriend called her and said she was feeling pretty bad and that she just didn’t think that she should go to the party and Anna was felt so bad about that, she didn’t really know if she wanted to go either. But anyway, she had all that lasagna so she decided that she really would want to go. And then at the party, uh I guess some uh, a friend of hers told her that she had spinach on her teeth that she better go and get that off so um she kinda felt kinda funny about that. Went to the restroom and took care of that and uh she was feeling kinda down, but then she heard some of the people talking about that wonderful lasagna.

Older Adult Reflection from 75-Year-Old Perspective

Uh, yes, David um first of all David uh was uh, getting ready to do his crossword puzzle and he was wondering what he was going to do for the weekend he remembered that he was going to have a potluck that weekend so what he did was he um decided what he was going to bring was lasagna but when he went to the cabinet to look in the cabinet uh David did not have no tomato sauce, so he didn’t want to go to the store so uh, cause he thought he’d bought enough groceries to last him, but anyway he had to get in the car, drive down to the store went and got his favorite lasagna, his favorite tomato sauce and then while he was at the store he saw the mangos on sale which was one of his favorite fruits which he really couldn’t afford but since they was on sale he bought three. As he was getting in line, he remembered that it was one of his friend’s birthdays that he had to get a card for which she always gave him a card but he never did give her a card. So I guess he picked her up a card and he came on home started reading uhh his crossword puzzle again and made him a cup of coffee and he decided he’d better get up and fix his lasagna. So he fixed his lasagna um made it he sit down and started reading his some more puzzles with his cat xxxx. Then I guess he decided ‘til it got late enough he then went to bed. Uh then he got up the next morning which he was going to go take him a uh brisk walk and as he was walking though town he came to the park he discovered that he had stepped on something squishy and soft under his shoe, which was dog poop. He was wondering if he could get the poop what’s going to go through his canvas of his shoe and he was real worried about that. So he kind of cleaned it off the best he could and after he did that he went uh to uh cleaned his poop off and he kept on and he came back home. Then he decided to fix him some breakfast. So then he’s fixing his breakfast and he decided to work a few more crossword puzzles and then the phone rang. Uh no. Uh he decided to eat breakfast uh so he ate his breakfast and then he decided to go out and do a few chores. He went and paid a few chores and then went a few places, hardware store, probably the bank, the gas light place, and he came back home. Then he was waiting for his friend Bob to come by so that he can go to the uh potluck for what he’d prepared for his lasagna was for the potluck for the weekend. And he waited for Bob his friend, then he called and said that he wouldn’t be able to make it and he’d never liked to go anyplace by himself.

Footnotes

Scaled Income: on a scale of 1–16 at intervals of $10,000 total household income for the last year; Self-Rated Health (Han, B., Phillips C., Ferrucci, L., Bandeen-Roche, K., Jylha, M., Kasper, J., & Guralnik, J.M., 2005): an overall rating of physical health on a scale of 1–5, superior health = 1.

Vocabulary from the WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997): maximum score = 66; Digit-Symbol Coding from the WAIS-III: maximum score = 133; Digit Span from the WAIS-III: maximum score = 30.

One older adult used zero negative words in the 75-year-old perspective condition; therefore in order to calculate the ratio of positive to negative words we substituted the next lowest reported negative word score for the zero value.

Previous research suggests that for emotional material in general, few age differences emerge in reported emotional intensity of experimental stimuli (for review, see Carstensen et al., 2006).

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this alternative interpretation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/pag

References

- Baltes PB, Staudinger UM, Maercker AS. People nominated as wise: A comparative study of wisdom-related knowledge. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:155–166. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:323–70. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F. Post-formal reasoning in socio-emotional context. In: Commons ML, Sinnott J, Richards F, Armon C, editors. Adult Development: Vol. 1. Comparisons and applications of developmental models. New York: Praeger; 1989. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Gardner WL, Berntson GG. Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: The case of attitudes and evaluative space. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1997;1:3–25. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0101_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz D, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA. At the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition: Aging and the Positivity Effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA, Mather M. Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation, and emotion. In: Birren JE, Schaire KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. A life-span view of emotional functioning in adulthood and old age. In: Costa P, editor. Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology Series: Vol. 15. Recent advances in psychology and aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- Chasseigne G, Lafon P, Mullet E. Aging and rule learning: The case of the multiplicative law. American Journal of Psychology. 2002;115:315–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluck J, Baltes PB. Using the concept of wisdom to enhance the expression of wisdom knowledge: Not the philosopher’s dream but differential effects of developmental preparedness. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:679–690. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Phillips C, Ferrucci L, Bandeen-Roche K, Jylha M, Kasper J, Guralnik JM. Change in self-rated health and mortality among community-dwelling disabled older women. Gerontologist. 2005;45:216–221. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Selective preference in visual fixation away from negative images in old age? An eye-tracking study. Psychology & Aging. 2006;21:40–48. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Q, Mather M, Carstensen LL. The role of motivation in the age-related positive bias in autobiographical memory. Psychological Science. 2004;15:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.01503011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryla-Lighthall N, Mather M. The role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional well-being. In: Bengtson VL, Silverstein M, Putney N, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. 2. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ligneau-Herve C, Mullet E. Perspective-taking judgments among young adults, middle-aged, and elderly people. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2005;11:53–60. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.11.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Aging, emotion, and health-Related decision strategies: Motivational manipulations can reduce age differences. Psychology & Aging. 2007;22:134–146. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini TS, Grusec JE, Bernardini SC. Effects of interpersonal control, perspective taking, and attributions on older mothers’ and adult daughters’ satisfaction with their helping relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:688–705. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science. 2003;14:409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Larkin GR, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Cartensen LL. Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: Changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:542–553. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC): A computerized text analysis program. Mahwah: Erlbaum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MW, Diessner R, Pratt A, Hunsperger B, Pancer SM. Moral and social reasoning and perspective taking later in life: A longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:66–73. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Robertson ER, Mikels JA, Carstensen LL, Gotlib IH. Selective attention to emotion in the aging brain. Psychology and Aging. doi: 10.1037/a0016952. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlagman S, Schulz J, Kvavilashvili L. A content analysis of involuntary autobiographical memories: Examining the positivity effect in old age. Memory. 2006;14:161–175. doi: 10.1080/09658210544000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM. Older and wiser? Integrating results on the relationship between age and wisdom-related performance. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1999;23:641–664. [Google Scholar]

- Wahler HJ. Wahler physical symptoms inventory. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein SR. Health Effects on cognitive aging. In: Stern PL, Carstensen LL, editors. The aging mind: Opportunities in cognitive research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. pp. 189–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Kisley MA. The negativity bias is eliminated in older adults: Age-related reduction in event-related brain potentials associated with evaluative categorization. Psychology and Aging. 2006;2:815–20. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm LH, Labouvie-Vief G, Aycock J, Rebucal KA, Koch HE. Performance in auditory and visual emotional stroop tasks: A comparison of older and younger adults. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:523–35. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]