Abstract

A major component of the adaptive immune response to infection is the generation of protective and long-lasting humoral immunity. Traditional approaches to understanding the host’s humoral immune response are unable to provide an integrated understanding of the antibody repertoire generated in response to infection. By studying multiple antigenic responses in parallel, we can learn more about the breadth and dynamics of the antibody response to infection. Measurement of antibody production following vaccination is also a gauge for efficacy, as generation of antibodies can protect from future infections and limit disease. Protein microarrays are well suited to identify, quantify and compare individual antigenic responses following exposure to infectious agents. This technology can be applied to the development of improved serodiagnostic tests, discovery of subunit vaccine antigen candidates, epidemiologic research and vaccine development, as well as providing novel insights into infectious disease and the immune system. In this review, we will discuss the use of protein microarrays as a powerful tool to define the humoral immune response to bacteria and viruses.

Keywords: antibody profile, antigen discovery, humoral immune response, infectious disease, protein microarray

The development of automated micro-deposition technology has allowed investigators to screen high-density protein arrays for enzyme–substrate, DNA–protein and protein–protein interactions [1,2]. These assays bring unique capabilities such as parallelism, high-throughput format and miniaturization, and are ideally suited to comprehensive investigation into the humoral immune response to infection. Protein microarrays can be used with relative ease to interrogate the entire proteome of infectious microorganisms, consisting of thousands of potential antigens. Arrays can be produced and screened in large numbers, while consuming only small quantities of individual sera (< 2 µl of sera per patient). This approach permits investigators to assess the repertoire of antibodies created in response to infections or vaccination from large collections of individual patient sera, and can be used to perform large-scale seroepidemiological, longitudinal and sero-surveillance analyses, which are not possible with other technologies. Moreover, microarrays can express all proteins of an infectious agent and may allow for the identification of novel antigens, otherwise undetectable by methods such as 2D gels that are highly influenced by microbial protein expression patterns. The powerful approach offered by protein arrays may also be able to better identify antigens that elicit an immunoreactive response under various stages of replication/infection, and thus provide new insights into the lifecycle of the microbe.

Conventional approaches to antigen discovery

Seroreactive antigen identification has typically been based on biochemical approaches or expression library screening. For example, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, antigens have been identified by screening proteins found in subcellular fractions of in vitro cultures and separated by 2D gel electrophoresis [3], screening recombinant expression libraries [4], or simply based on relative protein abundance and ease of purification from bacterial cultures [5]. Once a potential target is found, identification may involve laborious protein manipulation and expensive mass spectrometry. Electrophoretic separation and screening (e.g., using 2D gels) is a common method for measuring the humoral response on a broader scale, but is limited to proteins found in particular subcellular fractions or to highly expressed proteins, grown under specific conditions. Since growth conditions of a pathogen may significantly alter the profile of gene expression and protein levels, it is difficult to ascertain the physiological relevancy of obtained data. Often artefacts are introduced such as genomic deletion and attenuation, which may not reflect the natural lifecycle of infection. In some cases, culturing the pathogen (if possible) may be time consuming and potentially hazardous. While these approaches are able to identify antigens that are seroreactive to highly expressed proteins, the process often misses numerous, less abundant proteins that require identification by more sensitive assays. Moreover, traditional approaches may often be very time consuming, and difficult to recapitulate exactly by other laboratories. Furthermore, traditional approaches require large amounts of sera (> 500 µl) which is usually pooled from numerous patients, thus possibly eliminating unique patient-specific information. A microarray-based study by Eyles et al. highlights the advantages of this methodology over other established approaches. In this work the authors identified 11 of the top 12 Francisella tularensis antigens previously discovered by mass spectrometry and western blots, and an additional 31 unreported antigens [6]; establishing the conformity and superiority of protein microarrays for the identification of seroreactive peptides.

Antigen discovery approaches that involve construction of whole-genome ‘shotgun’ expression libraries have worked to identify a small number of antigenic proteins but, in this approach, some DNA inserts are over-represented and other immunologically important antigens may be under-represented. Screening of an expression library is laborious and requires several steps of re-probing to purify the ‘positive’ clones, which can then be sequenced. For screening methods that involve an intervening phage display step, it is common to select multiple phage colonies that display the same polypeptide, because certain polypeptides favor virus propagation and others do not. For the same reasons, ‘potential’ hits will simply not be in the library at all. Moreover, when the library is screened, it is exceedingly difficult to obtain quantitative data on antibody titers. Eventually, one needs to obtain a clone containing the full-length open reading frame by conventional methods (since most of the ‘positive’ primary clones will be partials), sequence again, purify the protein by conventional methods and test it in immunoassays by conventional methods.

Antigen discovery by protein microarrays

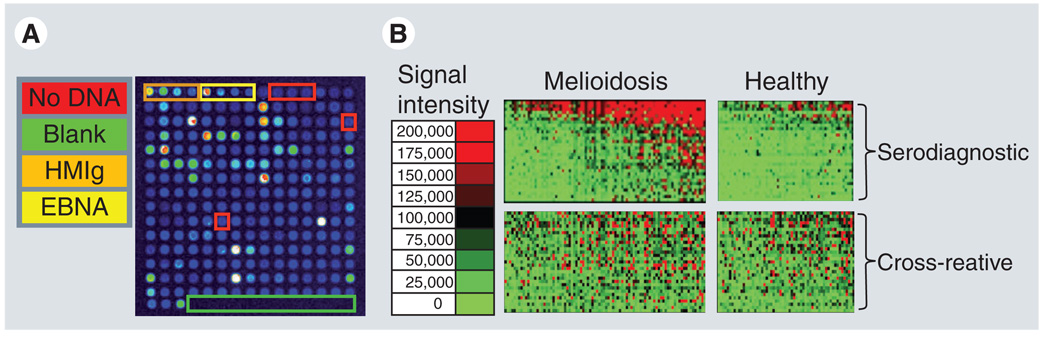

An example of a protein microarray readout for an individual patient sample, and corresponding heat map, are shown in Figure 1A & 1B, respectively. No other existing method can quantitatively and comprehensively interrogate the humoral immune response with comparable accuracy, efficiency and speed. Furthermore, microarrays require minute amounts of protein and can contain tens of thousands of individual proteins spotted on a single array, permitting a thorough investigation of the antibody response to an entire proteome.

Figure 1. Representative protein microarray image and population comparative analysis.

(A) A representative microarray image of sera from a melioidosis-positive patient screened for reactivity to a small collection of Burkholderia pseudomallei antigens. Seroreactivity is detected using a fluorescently labeled anti-human IgG antibody. The arrays were read in a laser confocal scanner and the signal intensity of each antigen is represented by rainbow palette of blue, green, red and white by increasing signal intensity. A representative microarray containing 214 B. pseudomallei proteins, positive and negative control spots is depicted in (A). Each array contains positive control spots printed from four serial dilutions of human IgG. Each array also contained six ‘No DNA’ negative control spots. There are also four serially diluted EBNA1 protein control spots which are reactive to varying degrees in different subjects, as expected, and provide a methodological control. The remaining spots on the array are in vitro transcription/translation reactions expressing 183 different B. pseudomallei proteins. (B) Seroreactivity of individual melioidosis-positive patients and healthy controls can be depicted in a heatmap. The patient samples are in columns and sorted left to right by increasing average intensity to serodiagnostic antigens. The antigens are in rows and are grouped according to differential reactivity. Differentially reactive antigens are considered serodiagnostic and similarly reactive antigens are considered cross-reactive. The normalized intensity is shown according to the colorized scale with red strongest, bright green weakest and black in between.

EBNA: Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen; HMIg: Human Ig.

Seroepidemiology by protein microarray

Protein microarrays permit investigation of individual patient humoral immune responses to infectious agents and provide a robust platform that can generate key insights into the host immune response to microbes, epidemiological research, vaccine development and diagnosis of infectious disease. With the ability to screen all potential antigens of a pathogen, independently of their abundance in the natural infection, one can better discover correlates of immune response, protection and disease progression. Uniquely, arrays can apply this level of specificity to large numbers of sera simultaneously. Whereas some traditional approaches utilize large amounts of sera, often requiring pooling of samples from multiple patients, microarrays can easily analyze individual patient samples since they require very small input volumes of 1–2 µl. A small sample requirement allows for screening of large collections of individual sera on a seroepidemiological scale, providing the statistical power to identify population-specific responses to single antigens. High-throughput screening of patients permits identification of common antigens under various infectious stages and conditions. This method may also allow for the discovery of novel mechanisms for immune intervention by discovering proteins that are transiently (or weakly) expressed, but can elicit protection from disease and may be used for diagnosis. This ability is unique in that it may correlate outcome of infection to other agents that would not be found, by looking at pooled samples where responses found in only some of the sera would be diluted below detection levels. In addition, unique patient profiles can allow an investigator to produce algorithms that can be applied to diagnostic devices, which must take into account subtle variations in the humoral immune response to a disease.

Limitations of the microarray approach

Protein microarrays are often limited by the difficulty and complexity of protein purification, as well as high-throughput gene expression systems. It is not always feasible to produce and purify the hundreds to thousands of proteins necessary for spotting the complete proteome of an infectious agent. Despite this labor-intensive limitation, successful attempts have been made using this strenuous method to generate protein microarrays for profiling the humoral immune response to infection [7–11]. In addition, protein microarrays may be limited in the study of humoral immune response to infectious disease owing to their inherent inability to identify nonprotein antigens, such as polysaccharides and glycolipids, although these molecules can be obtained by traditional methods and printed on the protein microarrays. Advances in microarray technology have expanded to utilizing nonprotein antigens, including membrane proteins [12], carbohydrates [13] and even live cells [14]. While it is true that advances in microarray technology have incorporated many of these molecules onto microarrays [15], investigation targeted towards the humoral immune response to infectious disease has focused mainly on antibody response to proteins. As the rapid inclusion of nonprotein molecules onto microarrays progresses, we expect a more complete picture of the repertoire of antibodies generated against infectious agents to emerge. Another limitation to protein microarrays is the complexity of protein folding and multimerization. The correct folding of some proteins or multimerization of proteins may be difficult or impossible to recreate on a microarray platform. Furthermore, verification of folding or multimerization may not be simple to comprehensively determine, and may require specific quality controls for each individual protein, significantly reducing throughput. Moreover, post-translational modifications (such as phosphorylation and glycoslyation) that are important for specific antibody interactions may not be reproducible through in vitro transcription and translation reactions and would not be identified. Utilization of yeast expression systems and further advances in a more complete characterization of the humoral immune response are quickly developing and will undoubtedly aid in the discovery of new immunoreactive antigens with various post-translational modifications.

Another limitation to protein arrays (like DNA microarrays) is the need for sophisticated statistical methods for interpreting results. Establishing standard criteria for array production and data normalization using noise models, variance estimation and differential expression analysis techniques would benefit interpretation of results [16–18]. Nonetheless, as this technology develops and becomes more established, we expect a comparative analysis of statistical methods and the emergence of several standardized analysis methods that can accurately report the humoral immune response to infectious agents.

General properties of antigenic proteins

Proteome-wide screening of immune sera can potentially identify hundreds of seroreactive antigens in a given pathogen. Grouping them by physical properties, function and cellular location is of importance for understanding the underlying rules of antigenicity and for the development of improved in silico predictive algorithms. The annotation provided with genome sequence databases commonly detail proteins according to their biological process, molecular function and cellular compartment. However, these are based on sequence homology with the relatively small number of proteins of known function, and are often unreliable and inconsistent between different sources. Comprehensive and standardized annotation processes are being implemented to solve these problems and will provide a greater source of reliability and consistency. Alternatively, computational prediction software such as pSORT and SignalP [19,20] provide additional avenues of classification and can be of significant importance to infectious agents that are poorly annotated. Computational prediction software is limited by inaccuracy inherent in the prediction algorithms inability to completely predict the function of every protein. Nonetheless, these programs are capable of defining a collection of antigens that are significantly enriched in seroreactive groups. For example, we have noticed immunogenic antigens from Coxiella burnetii [21] and F. tularensis [6,22] often have a bias for signal peptide-containing proteins. We have found that 20.5% of the reactive antigens to C. burnetii were predicted to be secreted into the periplasm or beyond, while only 10.2% of the proteome contains this feature. Even more striking is that 44% of the antigens reactive to F. tularensis contained a predicted signal sequence, compared with only 11% of all the proteins in the proteome as a whole. We have also found enriching features based on computational prediction of protein localization. For example, PSORTb predicted that extracellular proteins of Burkholderia pseudomallei were significantly enriched and cytoplasmic proteins were significantly underrepresented [23]. It is also likely that reactivity to proteins may be directly related to levels of protein expression. Proteins esxpressed in higher amounts may be preferentially recognized by the immune system compared with those that are less abundant. In addition, molecules with proteomic features that are under-represented may be expressed at high levels in vivo, making them targets for immune recognition independent of their predicted features. Other properties, such as a propensity for self assembly, exemplified by viral capsid and scaffold proteins, may also influence antigenicity [24]. In our experience, we have found that the immune response is not stochastic and, although certain protein annotation categories are enriched in the immunoreactive antigen lists, there is no predictive category that is entirely seroreactive. Protein microarrays can also be utilized to identify proteins that are not antigenic. For example, we found that 85% of the open reading frames in Borrelia burgdorferi from different stages of infection were not reactive [25], which may be due to the technical limitations of arrays that under-represent the true antibody profile (discussed earlier). This perspective on immune responses will also assist the development of predictive algorithms that will be able to utilize lack of reactivity as a tool to eliminate candidate diagnostic antigens, and better understand immune recognition and evasion.

Importantly, some proteins appear to be consistently antigenic. For example, we and others [26] have noticed that the heat-shock proteins (HSPs) from the GroES–GroEL family are often some of the most immunoreactive proteins. Immune responses to HSPs have been observed in infectious diseases caused by bacteria, protozoa, fungi and nematodes in numerous infection models. The GroEL HSP was significantly differentially reactive by protein microarray in infected sera for B. pseudomallei [23], Brucella melitensis [Felgner PL, Unpublished Data], C. burnetii, F. tularensis and B. burgdorferi. These results are consistent with previously published findings [27]. Owing to similarities in the HSP sequences between different infectious agents, they are often removed from consideration a priori as serodiagnostic targets because of the expectation that they will be cross-reactive and nonspecific. Our empirical analysis of several infectious agents has shown heat-shock targets are more specific than expected. High reactivity may indicate an essential role for this protein, sufficient to warrant high immunological pressure. However vaccination attempts using GroEL, while able to generate ample T- and B-cell responses, have largely shown modest therapeutic value. The inability to confer protection may be due to the high degree of sequence similarity with human hsp60 [28]. The significance of this commonality and a linkage to inflammatory disease is only now becoming clear [29].

Host responses to infection

The lifecycle of an infectious agent can have a significant impact on the type of humoral immune response generated, treatment approaches and diagnosis. The repertoire of expressed antigens during different stages of the pathogen’s lifecycle may be transient and hard to identify by traditional approaches. A well-studied example is the causative agent of malaria, the protozoan Plasmodium falciparum, which yields unique expression profiles for each stage of infection. For example, antibodies to the sporozoite threonine- and asparagine-rich protein antigen (expressed primarily in sporozoites), whether acquired naturally or through irradiated sporozoite immunization, have been shown to inhibit sporozoite invasion of human hepatocytes, whereas liver stage antigen-1-specific IgG (expressed primarily during the liver stage) has been associated with protection against liver-stage parasites [30]. While a blood-stage specific subunit vaccine, including ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen, merozoite surface protein-1 and -2, was able to demonstrate efficacy in reducing parasitemia in children enrolled in a Phase I/IIb trial in Papua New Guinea [31], it would not be expected to provide protection against the liver stage. Longitudinal profiling of the humoral immune response may be able to identify key antigens capable of limiting disease at distinct stages, track progression of the disease in an individual, lead to better understanding of the lifecycle of an infectious agent, and provide novel treatment approaches. Furthermore, the use of microarrays may include the markers for diagnosis of infection prior to the appearance of clinical symptoms, an important application for delayed, latent or asymptomatic infections.

Commonly, the majority of the immune response is directed to a few proteins within an infectious organism. These proteins are often less genetically conserved than other proteins and generally have multiple variants of the same gene. Another advantage of protein microarrays is their ability to express multiple variants of the same protein. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) encodes only eight proteins, but more than 100 types have been described [32]. Expression of all eight proteins by these 100 types would still be well within range of protein microarrays, where one can routinely spot several thousand individual proteins. Moreover, exclusion of all identical proteins can limit the total number of proteins to substantially less. For example, expression of all of the nonhomologous Var genes from P. falciparum clone 3D7 would include only 59 highly polymorphic genes. Expression of all Var genes from all four species of Plasmodium that infect humans would produce fewer antigens than most proteome protein microarrays can accommodate.

Cross-reactivity versus specificity in the antibody response

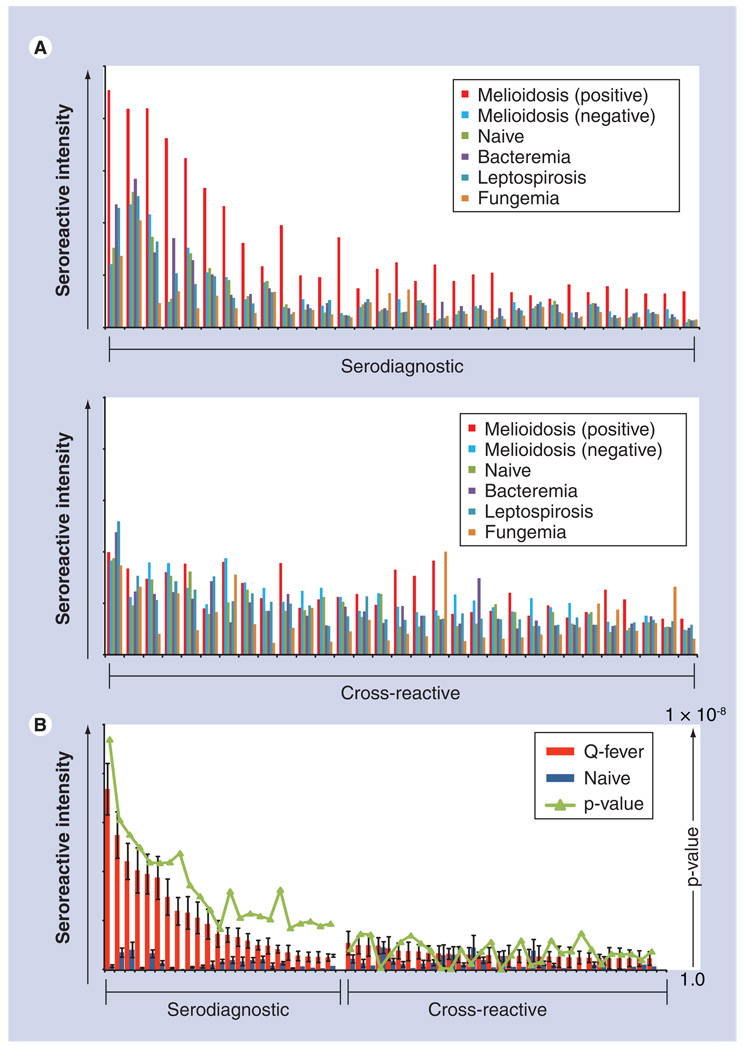

The immune response generated against an infectious organism has to be effective enough to eliminate the invading species, while allowing commensal flora to survive and flourish. Antibodies specific to infectious agents follow the dogma that an immune response is generated to combat the infection and cause no harm to the host. Cross-reactive antibodies are thought to exist as a consequence of an indiscriminate or broad antibody response against numerous pathogens (whether symbiotic or not), but may have other, more complex, causes. Interestingly, the immense diversity of potential antibodies generated against an infectious pathogen is often limited to a select handful of antigens. A delicate balance between a susceptible reservoir versus immunogenicity and host health underlines the relationship between host and pathogen. Understanding this relationship between pathogen evasion and the immune system is critical to the generation of better vaccine design strategies. Immunological pressure is put on the microbe by antigen-specific antibodies regardless of whether they are specific to the infectious agent or cross-reactive to many infectious species. Cross-reactivity can occur between phylogenetically distant species, such as helminths and protozoans [33] or, alternatively, allow single amino acid changes to release strains of influenza from immunological pressure [34]. Interestingly, some antigen-specific antibodies may have adverse effects on the host, as described with the dengue-specific humoral immune response, following secondary exposure to alternative serotypes, and the antibody-dependent enhancement of infection [35] and association with dengue hemorrhagic fever [36,37]. While cross-reactivity between different pathogens may be disregarded as unimportant ‘background’ reactivity, as seen in western blots, this conclusion cannot be as easily determined physiologically, and is important to detail in microarray reports. For example, a large degree of cross-reactivity to Burkholderia has been observed in our recent work [23]. Figure 2A shows preliminary results of antibody response to infection with Burkholderia in comparison to other infections and naive controls. This cross-reactivity may have important implications for the efficacy of vaccines, memory response and, ultimately, susceptibility to infection. It may also have important evolutionary implications for Burkholderia and cross-reactive partners that are more closely related (B. mallei, B. thailandensis and B. oklahomensis), as well as the more distantly related, plant-associated Burkholderia spp. The degree of cross-reactivity is often highly variable and in some cases almost nonexistent or nonlinear in relation to phylogenetic distance [38]. In contrast to Burkholderia, Figure 2B shows almost no cross-reactivity to C. burnetii from naive samples. Coxiella is considered to be the most infectious agent, with a median infective dose of 1. This low level of cross-reactivity may have important consequences for determining exposure risk and infectious dose, and also for relative efficacy of subunit vaccines and strategies for improved vaccine development. In addition, a microbe may adopt strategies to promote cross-reactivity to other diseases or mimic host molecules, and arrays can provide an important understanding of how latent pathogens or persistent infections overcome the immunized host in order to replicate and spread under conditions where high titer IgGs are present as a result of initial infection. Cross-reactivity may also explain susceptibility of immunocompromised patients to certain infections, development of autoimmunity, correlations of pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of disease.

Figure 2. Comparison of cross-reactivity to Burkholderia pseudomallei and Coxiella burnetti.

(A) The mean seroreactivity was compared between melioidosis positive, melioidosis negative, healthy naives from a nonendemic region, and other infections. The 31 most reactive serodiagnostic and 31 of the most reactive cross-reactive antigens are shown. Differentially reactive antigens are shown in the top graph and have a p-value of less than 0.05. Cross-reactive antigens are similarly reactive in all groups and have an analysis of variance p-value of 0.08. (B) The mean seroreactivity to C. burnetii was compared with Q-fever-positive patients and naive controls. Naive controls display low reactivity to many antigens and many serodiagnostic antigens are distinctly different in patients with Q-fever.

Vaccine development

An important aspect of defining the humoral immune response to infectious agents by microarray is in the development of existing vaccines and improvement of current vaccines for both humans and animals. Protein microarrays can be applied to defining the immunogenicity of vaccine formulations, identifying potential vaccine antigen candidates, determining vaccine efficacy and longevity, and identifying correlates of protection and surrogate end points in animal models and human subjects. Using a full proteome-inclusive approach, potential antigen candidates capable of generating protective immunity can be identified without prior knowledge of the antigen’s abundance, immunogenicity or expression kinetics during infection. A combined full proteome screen and high-throughput approach can lead to identification of immunogenic proteins that are seen in patients responding well to treatment, vaccination or that are immune to infection. This approach can identify single or groups of antigens that correlate with effective treatment response and protection. In contrast, other available methods for determining correlates of immune response typically require large amounts of sera, may overlook less-expressed proteins and utilize pooled samples, thus missing unique patterns from individual patients.

In vaccine development, pathogen antigenic variations, strain diversity and predisposition to mutate under immunologic pressure, are complicating factors that have historically been addressed empirically, often in painstakingly slow studies. Protein microarrays, capable of accommodating hundreds of known microbe sequence variations, may provide an approach to overcome these complications. By taking into account numerous genetic variations of circulating pathogen strains and the respective antibody response to these variations, it should be possible to design vaccines that are able to elicit a strong humoral response against the majority of strains and antigen variants. Empirical evidence from past vaccine development demonstrates that a broader immunity, inducing both antibodies and cellular immune responses, provides better protection and longer lasting immunity (reviewed in [39]). An effective vaccine would ideally induce long-lived immunologic memory that will produce adequate levels of specific antibodies rapidly upon pathogen re-exposure. Either the vaccine-induced antibodies must be targeted against conserved epitopes, regions unlikely to mutate, or the vaccine must include antigens from each relevant strain. The need to target multiple antigens is exemplified by the current HPV vaccine, which protects against four types of HPV; and the seasonal trivalent flu vaccine, which protects against two types of influenza (A and B) and two strains of influenza A. While long-sought, the development of a universal vaccine against influenza has been elusive. Quantitative profiling of the humoral immune response that details the extent and diversity of antibody profiles of a population would improve the development of more effective annual influenza vaccines. The use of this information could improve strain selection in the annual vaccine by providing an antibody profile of the population prior to the flu season. A recent report described the generation of monoclonal antibodies to the 1918 influenza virus from individuals born in or before 1915 [40]. The authors were able to discover life-long circulating memory B cells that produce virus neutralizing antibodies to this uniquely virulent strain of influenza. The role of prior exposure in vaccine efficacy and heterosubtypic immunity may have important consequences [41]. Elderly patients vaccinated or infected with newly circulating strains of influenza can misdirect the immune response targeted to previously encountered antigens – a phenomenon termed original antigenic sin. This preferential induction of antibodies to nonoptimal antigens may play a larger role in the ineffective development of some subunit vaccines. Increasing the humoral immune response in individuals who have been repeatedly immunized or exposed to an infectious agent (or cross-reacting antigen) is often difficult. Consequently, the identification of and immunization with specific antigens rather than whole organisms is desirable.

An essential part of vaccine development is the induction of antibody-mediated protection directed against toxins, encapsulated bacteria and many viruses. The ability of a pathogen to infect and replicate in a host is limited by the generation of antibodies from vaccines or natural exposure. The development of subunit vaccines (and inactivated viruses) was meant to ameliorate the various manufacturing complications using related or attenuated strains of a pathogen. The ability to quickly, comprehensively and quantitatively identify potential candidates for effective subunit vaccines is available with protein microarrays. Microarrays are also well suited for determining vaccine efficacy profiles against infectious agents, where human trials may not be available. For example, since it is no longer possible to evaluate the efficacy of new-generation smallpox vaccines in humans, estimates can be made from animal models, and correlates of protection can be applied to human response to vaccination. Davies et al. were able to determine that, despite deletion of several genes from the modified vaccinia Ankara genome, there was little impact on the profile of antibodies to membrane proteins and thereby limited impact on the neutralizing antibody response [42]. However, a simple comparison of serum antibody levels between vaccines is not sufficient to derive conclusions of superiority. For example, the ability to limit intestinal infection was of significant importance in the choice between the oral polio vaccine and the inactivated polio vaccine [39], and considerations of cell-mediated responses should be determined. While microarray data can provide significant insight into the humoral immune response to a vaccine, an absolute determination of superiority cannot be obtained from this single element of immunity.

Diagnostic development

An urgent need exists to more rapidly assess the presence, prevalence and spread of newly emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases, as well as detecting the intentional introduction of biowarfare agents. Similarly, laboratory-based early warning systems are needed to ascertain whether or not previously uninfected military or civilian personnel passing through geographical regions with known endemic or epidemic infectious disease activity have been exposed to category A, B or C infectious agents. Improved rapid diagnostic methods are needed for public health agencies to better monitor changes in the prevalence of emerging infectious diseases. Antigens that are better serodiagnostic markers of infection can be identified by multiplex assays. These antigens can then be utilized in other, well-established platforms such as ELISA or immunostrip. Importantly, by identifying multiple serodiagnostic antigens, one can establish a minimal set of antigens necessary for discrimination between infected individuals and different infectious agents. Since infected patients do not react equally to infectious agents, there will be a percentage of the patient population that will not react to a particular serodiagnostic antigen, leading to a false-negative result. Inclusion of multiple serodiagnostic antigens into diagnostic tests can reduce false negatives and increase the overall assay sensitivity. We have consistently observed that single antigen determinates are inferior to diagnosis when compared with multiple independent serodiagnostic antigens. The ability to discover diagnostic antigens becomes prohibitively more difficult with an increased genome size. The genomes of B. burgdorferi, Chlamydia spp, M. tuberculosis and P. falciparum encode more than 850, 900, 4000 and 6000 genes, respectively. The use of robotics and other high-throughput technologies, such as microarrays, is needed to identify unique highly specific antigens for diagnostics. Protein microarrays offer significant improvements in convenience and cost for the discovery of diagnostic antigens for infectious disease, allergies, cancer and autoimmunity. For example, protein microarrays for Toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes antigens produced similar results obtained using the standard ELISA diagnostic with increased convenience and lower cost [43]. Multiplex protein microarrays will be useful for assessing the spread of exposure in a population following a bioterrorism attack, reducing time consumption, reducing reagents/sample use for diagnosis, tracking annual changes in the prevalence of infections in endemic regions and for monitoring the blood supply in developing countries.

Conclusion

The humoral immune response to infectious disease is often broad and multifaceted. By nature, this type of response provides the most comprehensive approach to combating an infection, and generates the greatest potential for mounting effective protective immunity. The measurement of antibodies generated by immunization or natural infection is often a gauge for protective efficacy, as observed by passive administration of vaccine-induced antibodies, which can prevent disease and transmission to susceptible contacts. The development of antibodies against numerous epitopes on an antigen may increase the efficacy of protection by limiting the generation of escape mutants. Studies on the characteristics of individual antibodies, and the antigen-specific B cells that produce these epitope-specific antibodies, may not distinguish the forest from the trees, and one may miss the choreographed response between host and microbe. By using protein microarrays to profile the immune response, one may gain a significant understanding of this process. This type of array can comprehensively measure the humoral response to an entire proteome of an infectious agent in an antigen- and patient-specific manner.

High-density protein arrays remain difficult to generate and are not currently a conventional tool in most laboratories. A major limitation is the need for a combination of high-throughput cloning and high-throughput protein expression. Alternative, more arduous methods have been used by many groups to circumvent these obstacles and demonstrate the desire to generate these arrays. A summary of the advantages and limitations of protein microarrays is shown in Table 1. Protein microarrays can be useful for profiling immunoreactivity on a genome-wide scale, allow for high detection sensitivity, can be used to screen individual sera from large collections of samples and can be probed quickly. For example, our laboratory has made 31,000 plasmids encoding proteins derived from 25 infectious microorganisms, printed 20,000 protein microarrays and probed them with sera from more than 8000 different patients worldwide. A single individual can clone more than 300 genes in a day (the vaccinia proteome was completed in 3 days and the M. tuberculosis proteome was completed in less than 6 months), and probe microarray chips with 100 different sera samples per day. These capabilities make protein microarrays a unique tool for defining the humoral immune response to infectious disease. The microarray method provides a robust approach for characterizing the immune response and may lead to a more thorough understanding of the biology of infectious agents and their respective host’s immune systems. The data gathered can then be utilized for the discovery of serodiagnostic antigens, prediction of potential antigens for vaccine targets, vaccine efficacy profiling and used to validate and improve in silico antigen prediction algorithms. Importantly, the ability to understand the relationship between the large repertoires of antibodies generated in response to infectious disease can provide new insight into the mechanism of the humoral immune response.

Table 1.

Advantages and limitations of protein microarrays to define the humoral immune response to infection.

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Does not require handling infectious agent | May not recognize misfolded or multimeric proteins |

| Not restricted to resolution parameters, protein abundance, growth conditions or stage of replication/infection |

Requires additional procedures for identification of post-translation modifications or nonprotein antigens |

| Requires small amounts of sera and capable of high-throughput probing for epidemiological studies |

Requires expensive fluorescent microarray scanner and sophisticated statistical methods |

| Inexpensive and easy to learn probing (can be done in remote locations) |

Requires expensive robotics for printing arrays |

Future perspective

DNA microarrays are regarded as one of the most powerful available tools for understanding the relationship between large repertoires of genes. Similarly, protein microarrays will have significant influence in understanding and defining the humoral immune response between large repertoires of proteins for epidemiologic research, vaccine development and the diagnosis and treatment of allergies, autoimmune and infectious diseases. The importance of antibody-mediated protection is observed in immune response evolution, the maternal antibody-mediated transfer system, vaccine efficacy, and prophylactic and therapeutic treatments [44]. Antibody-mediated responses are most commonly harnessed for the prevention of measles, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, tetanus, varicella, rabies and vaccinia. Antibody treatment is also used in liver transplant patients with hepatitis B in order to lower the risk of developing hepatitis in the transplanted liver. Although their use in the treatment of bacterial infection has largely been supplanted by antibiotics, antibodies remain a critical component for the treatment of diptheria, tetanus and botulism. Growing concerns about the development of antibiotic-resistant strains, and the relatively recent clinical successes of recombinant antibodies for the treatment of cancer, has led to an increasing consideration of recombinant antibodies for infectious disease treatment. In the preantibiotic era pathogen-specific sera (serum therapy) from animals was commonly used against numerous viral and bacterial infections. Today, the licensing of therapeutic antibodies to the public is seen with anti-TNF-α for arthritis therapy, anti-HER2 for cancer therapy, and palivizuman for respiratory syncytial virus infection. In addition, prophylactic antibody treatment of viral infection has a shown therapeutic benefit for parvovirus, vaccinia virus and enterovirus infections. The requirement for new vaccines and antibody-mediated therapies will undoubtedly grow with the emergence of new pathogens, re-emergence of old pathogens, treatment of immunocompromised individuals and the increasing number of antimicrobial-resistant infectious agents (Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus species and Streptococcus pneumoniae). Widespread emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria serves as a critical warning sign, requiring aggressive investigation of alternative therapeutic approaches, such as monoclonal antibody therapy or vaccine development. Complete proteome analysis allows for the discovery of monoclonal antibodies against key bacterial epitopes, with resultant significant therapeutic benefit. In the development of antibody therapies the identification of immunogenic targets is of high importance and the use of protein microarrays for selection of target antigens will be vital. This approach is particularly promising for the development of antibody therapies and subunit vaccines against infectious agents that contain hundreds to thousands of potential candidate targets.

Executive summary

General properties of antigenic proteins

Computational prediction software for the annotation of microbes with large and uncharacterized proteomes is essential to understanding the immune response to infectious disease in the context of protein physical properties, function and cellular location.

Protein annotation can be used to identify predictive features of proteins that may be immunogenic, although, as of yet, there is no single predictive feature for seroreactivity.

Host responses to infection

Understanding the relationship between pathogen evasion and the immune system is critical for the generation of better vaccine design strategies.

The physiological importance of specific and cross-reactive antibodies to an infectious agent may have important implications for microbe evolution, susceptibility to infection, latency, autoimmunity, pathogenesis, diagnosis and vaccine development.

Vaccine development

Comprehensive profiling of the humoral immune response to an infectious agent may lead to better vaccine development and efficacy.

Protein microarrays are well suited for determining vaccine efficacy profiles against infectious agents, where human trials may not be available.

Diagnostic development

Protein microarrays provide a robust platform for the discovery of serodiagnostic markers of infection.

Protein microarrays offer significant improvements in throughput, convenience and cost for the discovery of diagnostic antigens for infectious disease, allergies, cancer and autoimmunity.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact: reprints@futuremedicine.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Philip L Felgner and D Huw Davies have patent applications related to protein microarray fabrication and have stock positions with Antigen Discovery, Inc. This work was supported in part by NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants (U01A1061363 and U54065359) to Philip L Felgner. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Adam Vigil, University of California Irvine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, 3501 Hewitt Hall, Irvine, CA 92697, USA, Tel.: +1 949 824 7368, Fax: +1 949 824 0481, vigila@uci.edu.

D Huw Davies, University of California Irvine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, 3501 Hewitt Hall, Irvine, CA 92697, USA, Tel: +1 949 824 0375, Fax: +1 949 824 5490, ddavies@uci.edu.

Philip L Felgner, University of California Irvine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, 3501 Hewitt Hall, Irvine, CA 92697, USA, Tel.: +1 949 824 1407, Fax: +1 949 824 5490, pfelgner@uci.edu.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.MacBeath G, Schreiber SL. Printing proteins as microarrays for high-throughput function determination. Science. 2000;289(5485):1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emili AQ, Cagney G. Large-scale functional analysis using peptide or protein arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18(4):393–397. doi: 10.1038/74442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samanich KM, Belisle JT, Sonnenberg MG, Keen MA, Zolla-Pazner S, Laal S. Delineation of human antibody responses to culture filtrate antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;178(5):1534–1538. doi: 10.1086/314438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manca C, Lyashchenko K, Wiker HG, Usai D, Colangeli R, Gennaro ML. Molecular cloning, purification, and serological characterization of mpt63, a novel antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 1997;65(1):16–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.16-23.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel TM, Ferguson LE. Purification and characterization of two proteins from culture filtrates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis h(37)ra strain. Infect. Immun. 1970;1(2):164–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.1.2.164-168.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyles JE, Unal B, Hartley MG, et al. Immunodominant Francisella tularensis antigens identified using proteome microarray. Proteomics. 2007;7(13):2172–2183. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu H, Hu S, Jona G, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome diagnostics using a coronavirus protein microarray. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(11):4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510921103. ▪ Well-designed study of a SARS protein microarray using purified proteins.

- 8.Steller S, Angenendt P, Cahill DJ, Heuberger S, Lehrach H, Kreutzberger J. Bacterial protein microarrays for identification of new potential diagnostic markers for Neisseria meningitidis infections. Proteomics. 2005;5(8):2048–2055. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keasey SL, Schmid KE, Lee MS, et al. Extensive antibody cross-reactivity among infectious Gram-negative bacteria revealed by proteome microarray analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8(5):924–935. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800213-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li B, Zhou D, Wang Z, et al. Antibody profiling in plague patients by protein microarray. Microbes Infect. 2008;10(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Bruno JF, Luft BJ. Profiling the humoral immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi infection with protein microarrays. Microb. Pathog. 2008;45(5–6):403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Y, Frutos AG, Lahiri J. Membrane protein microarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(11):2394–2395. doi: 10.1021/ja017346+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin I, Cho JW, Boo DW. Carbohydrate arrays for functional studies of carbohydrates. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2004;7(6):565–574. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziauddin J, Sabatini DM. Microarrays of cells expressing defined cDNAs. Nature. 2001;411(6833):107–110. doi: 10.1038/35075114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong M, Jacobi CE, Van De Rijke FM, et al. A multiplexed and miniaturized serological tuberculosis assay identifies antigens that discriminate maximally between TB and non-TB sera. J. Immunol. Methods. 2005;301(1–2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sundaresh S, Doolan DL, Hirst S, et al. Identification of humoral immune responses in protein microarrays using DNA microarray data analysis techniques. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(14):1760–1766. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl162. ▪ Description of analytical approaches to protein microarrays from proven methods and tools of DNA microarrays.

- 17. Marina O, Biernacki MA, Brusic V, Wu CJ. A concentration-dependent analysis method for high density protein microarrays. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7(5):2059–2068. doi: 10.1021/pr700892h. ▪ Shows that proper data analysis including protein concentration is essential for reliable statistical interpretation.

- 18.Zhu X, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Procat: a data analysis approach for protein microarrays. Genome Biol. 2006;7(11):R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardy JL, Laird MR, Chen F, et al. Psortb v.2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(5):617–623. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: signalp 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340(4):783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beare PA, Chen C, Bouman T, et al. Candidate antigens for Q fever serodiagnosis revealed by immunoscreening of a Coxiella burnetii protein microarray. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15(12):1771–1779. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundaresh S, Randall A, Unal B, et al. From protein microarrays to diagnostic antigen discovery: a study of the pathogen Francisella tularensis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(13):i508–i518. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Felgner PL, Kayala MA, Vigil A, et al. A Burkholderia pseudomallei protein microarray reveals serodiagnostic and cross-reactive antigens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(32):13499–13504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812080106. ▪ An extensive interrogation of the empirically determined antibody repertoire to bacterial infection.

- 24.Jing L, Davies DH, Chong TM, et al. An extremely diverse CD4 response to vaccinia virus in humans is revealed by proteome-wide T-cell profiling. J. Virol. 2008;82(14):7120–7134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00453-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbour AG, Jasinskas A, Kayala MA, et al. A genome-wide proteome array reveals a limited set of immunogens in natural infections of humans and white-footed mice with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2008;76(8):3374–3389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00048-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zugel U, Kaufmann SH. Immune response against heat shock proteins in infectious diseases. Immunobiology. 1999;201(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(99)80044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinnick TM. Heat shock proteins as antigens of bacterial and parasitic pathogens. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1991;167:145–160. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75875-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda H, Miyamoto M, Kokeguchi S, et al. Epitope mapping of heat shock protein 60 (GroeL) from Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2000;28(3):219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Eden W, Van Der Zee R, Prakken B. Heat-shock proteins induce T-cell regulation of chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5(4):318–330. doi: 10.1038/nri1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasquetto V, Fidock DA, Gras H, et al. Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite invasion is inhibited by naturally acquired or experimentally induced polyclonal antibodies to the starp antigen. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27(10):2502–2513. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genton B, Betuela I, Felger I, et al. A recombinant blood-stage malaria vaccine reduces Plasmodium falciparum density and exerts selective pressure on parasite populations in a Phase 1–2B trial in Papua New Guinea. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185(6):820–827. doi: 10.1086/339342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, Zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mwatha JK, Jones FM, Mohamed G, et al. Associations between anti-Schistosoma mansoni and anti-Plasmodium falciparum antibody responses and hepatosplenomegaly, in Kenyan schoolchildren. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(8):1337–1341. doi: 10.1086/368362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koelle K, Cobey S, Grenfell B, Pascual M. Epochal evolution shapes the phylodynamics of interpandemic influenza A (H3N2) in humans. Science. 2006;314(5807):1898–1903. doi: 10.1126/science.1132745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morens DM, Halstead SB. Measurement of antibody-dependent infection enhancement of four dengue virus serotypes by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 1990;71(Pt 12):2909–2914. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-12-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Endy TP, Nisalak A, Chunsuttitwat S, et al. Relationship of preexisting dengue virus (DV) neutralizing antibody levels to viremia and severity of disease in a prospective cohort study of DV infection in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189(6):990–1000. doi: 10.1086/382280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman AL. Dengue: defining protective versus pathologic immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113(7):946–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI21512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gog JR, Grenfell BT. Dynamics and selection of many-strain pathogens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(26):17209–17214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252512799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambert PH, Liu M, Siegrist CA. Can successful vaccines teach us how to induce efficient protective immune responses? Nat. Med. 2005;11 4 Suppl.:S54–S62. doi: 10.1038/nm1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu X, Tsibane T, McGraw PA, et al. Neutralizing antibodies derived from the B cells of 1918 influenza pandemic survivors. Nature. 2008;455(7212):532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature07231. ▪ Discovery of life-long memory B-cells to the pandemic 1918 influenza virus.

- 41.Bodewes R, Kreijtz JH, Rimmelzwaan GF. Yearly influenza vaccinations: a double-edged sword? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2009;9(12):784–788. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies DH, Wyatt LS, Newman FK, et al. Antibody profiling by proteome microarray reveals the immunogenicity of the attenuated smallpox vaccine modified vaccinia virus ankara is comparable to that of dryvax. J. Virol. 2008;82(2):652–663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01706-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bacarese-Hamilton T, Mezzasoma L, Ardizzoni A, Bistoni F, Crisanti A. Serodiagnosis of infectious diseases with antigen microarrays. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;96(1):10–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02111.x. ▪ Comparison of protein microarrays as an enhanced serodiagnostic divice compared with existing Toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes diagnostics ELISA methods.

- 44.Keller MA, Stiehm ER. Passive immunity in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13(4):602–614. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.602-614.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]