Abstract

In contrast to mammals, the spinal cord of adult zebrafish has the capacity to reinitiate generation of motor neurons after a lesion. Here we show that genes involved in motor neuron development, i.e., the ventral morphogen sonic hedgehog a (shha), as well as the transcription factors nkx6.1 and pax6, together with a Tg(olig2:egfp) transgene, are expressed in the unlesioned spinal cord of adult zebrafish. Expression is found in ependymoradial glial cells lining the central canal in ventrodorsal positions that match expression domains of these genes in the developing neural tube. Specifically, Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells, the adult motor neuron progenitors (pMNs), coexpress Nkx6.1 and Pax6, thus defining an adult pMN-like zone. shha is expressed in distinct ventral ependymoradial glial cells. After a lesion, expression of all these genes is strongly increased, while relative spatial expression domains are maintained. In addition, expression of the hedgehog (hh) receptors patched1 and smoothened becomes detectable in ependymoradial glial cells including those of the pMN-like zone. Cyclopamine-induced knock down of hh signaling significantly reduces ventricular proliferation and motor neuron regeneration. Expression of indicator genes for the FGF and retinoic acid signaling pathways was also increased in the lesioned spinal cord. This suggests that a subclass of ependymoradial glial cells retain their identity as motor neuron progenitors into adulthood and are capable of reacting to a sonic hedgehog signal and potentially other developmental signals with motor neuron regeneration after a spinal lesion.

Introduction

Adult zebrafish, in contrast to mammals (Ninkovic and Götz, 2007; Bareyre, 2008), regenerate severed axons from the brainstem (Becker et al., 1997), and regain motor function (van Raamsdonk et al., 1998; Becker et al., 2004) after a spinal transection lesion. Spinal motor neurons that are lost after a lesion also regenerate (Reimer et al., 2008), similar to other teleost species (Kirsche, 1950). Initially, newly generated motor neurons are clearly discernable from resident motor neurons by their small diameter. However, regenerated motor neurons in zebrafish fully mature as indicated by expression of choline acetyltransferase at later stages. Moreover, elaboration of peripheral axons and soma coverage with synaptic markers suggest network integration of regenerated motor neurons. Lineage tracing experiments indicate that regenerated motor neurons likely derive from proliferating Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells, which line the central canal and contact the pial surface with their endfeet (Reimer et al., 2008). Under non-lesion conditions these cells only produce oligodendrocytes (Park et al., 2007). In the spinal cord of adult mammals, similar cells with stem cell potential exist (Shihabuddin et al., 2000; Meletis et al., 2008). However, motor neuron differentiation has never been observed in vivo (Ohori et al., 2006; Meletis et al., 2008).

To elucidate how motor neuron regeneration in adult zebrafish is induced, we decided to investigate the role of the transcription factors nkx6.1, pax6 and olig2, as well as hedgehog (hh) signaling. These factors are crucial for motor neuron generation in the developing spinal cord (Ingham and McMahon, 2001; Varjosalo and Taipale, 2008), together with FGF and retinoic acid signaling (Novitch et al., 2003). Moreover, sonic hedgehog (Shh) is important for adult neurogenesis in the mammalian forebrain (Lai et al., 2003; Machold et al., 2003).

hh family genes are expressed in the embryonic floor plate [sonic hedgehog a (shha) and shhb in zebrafish] and instruct the formation of transcription factor domains along the ventrodorsal axis in the spinal cord (Krauss et al., 1993; Currie and Ingham, 1996; Avaron et al., 2006). The ventrolateral motor neuron progenitor (pMN) domain expresses a combination of nkx6.1, pax6, and olig2 in all vertebrates, including zebrafish, and gives rise to motor neurons that express to transcription factors hb9 and islet-1/-2 (Jessell, 2000; Cheesman et al., 2004; Park et al., 2004; Fuccillo et al., 2006).

hhs act by binding to the receptor Patched1, leading to derepression of the transmembrane protein Smoothened, which in turn leads to Gli-mediated activation of target genes. These include patched1 itself as part of an autoregulatory feedback loop in zebrafish (Concordet et al., 1996) and other vertebrates (Dessaud et al., 2008).

We find shha-expressing and pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells (defined by expression of Tg(olig2:egfp), Nkx6.1, and Pax6) in the unlesioned adult spinal cord, despite the absence of adult motor neuron generation. However, during lesion-induced motor neuron regeneration, numbers of pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells and expression levels of shha, patched1, smoothened, olig2, Nkk6.1, and Pax6, as well as FGF and retinoic acid pathway genes are greatly enhanced. Blocking hh signaling in adult fish in vivo impairs motor neuron regeneration. This suggests an important role for Shh and possibly other developmental signals in adult motor neuron regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All fish are kept and bred in our laboratory fish facility according to standard methods (Westerfield, 1989), and all experiments have been approved by the British Home Office. We used wild-type (wik), Tg(hb9:gfp) (Flanagan-Steet et al., 2005), Tg(olig2:egfp) (Shin et al., 2003), and Tg(shha:gfp) (Shkumatava et al., 2004) transgenic fish.

Spinal cord lesion.

As described previously (Becker et al., 1997), fish were anesthetized by immersion in 0.033% aminobenzoic acid ethyl methyl ester (MS222; Sigma) in PBS for 5 min. A longitudinal incision was made at the side of the fish to expose the vertebral column. The spinal cord was completely transected under visual control 4 mm caudal to the brainstem-spinal cord junction.

Intraperitoneal substance application.

Animals were anesthetized and intraperitoneally injected. Cyclopamine was purchased from LC Laboratories. Specific activity of cyclopamine was tested by incubating embryos with the substance, as describe previously (Park et al., 2004). This treatment resulted in cyclopia and loss of motor axons. The related control substance tomatidine (Sigma-Aldrich) had no effect (data not shown). For intraperitoneal injections into adult fish, cyclopamine and tomatidine were dissolved in 45% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) and injected at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml in a volume of 25 μl (equaling 10 mg/kg) (Sanchez and Ruiz i Altaba, 2005) at 3, 6, and 9 d postlesion. Analysis took place at 14 d postlesion.

Immunohistochemistry.

We used mouse-anti Pax6 (kindly provided by V. van Heyningen, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK) and rabbit anti-Pax6 (Covance, 1:300; both Pax6 antibodies showed identical results), mouse anti-Nkx6.1 (AB2024, 1:1000; kindly provided by O. Madsen, Hagedorn Research Institute, Gentofte, Denmark, and F55A10, purchased from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), and mouse anti-PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) (PC10, 1:500, Dako Cytomation) antibodies. Secondary Cy2-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.. Animals were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and postfixed at 4°C overnight. Spinal cords were dissected, and floating sections (50 μm thickness) were produced with a vibrating blade microtome (Microm). Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections for 1 h in citrate buffer (10 mm sodium citrate in PBS, pH = 6.0) at 85°C for 30 min for Nkx6.1, Pax6, and PCNA immunohistochemistry. All other steps were performed in PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Sections were blocked in goat serum (15 μl/ml) for 30 min, incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight, washed three times 15 min, incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h, washed again, mounted in 70% glycerol, and analyzed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss Axioskop LSM 510). Colabeling of cells was always determined in individual optical sections.

In situ hybridization. We used previously published probes to detect shha (Krauss et al., 1993), patched1 (Concordet et al., 1996), smoothened (Varga et al., 2001), and olig2 (Park et al., 2002) mRNAs. The in situ hybridization procedure on vibratome sections (50 μm thickness) followed a previously published protocol (Lieberoth et al., 2003).

Retrograde axonal tracing.

Retrograde axonal tracing from a spinal level 3.5 mm caudal to the transection site has been described (Becker et al., 1997). Briefly, biocytin was applied to the spinal cord and the tracer was allowed to be retrogradely transported to the somata of brainstem neurons with regenerated spinal axons overnight. Fish were perfused and labeled profiles were analyzed in vibratome sections (50 μm thickness) of the entire brain.

Behavioral assays of functional recovery.

We tested the endurance of unlesioned and lesioned fish by recording the time they were able to keep their position while swimming against a water current in an adaptation of a published protocol (van Raamsdonk et al., 1998). In a tunnel with a flat bottom (7 cm width), 15 cm long compartments were divided off by wire mesh. A current of 15 cm/s was induced using a pond pump (Nautilus 8000, Oase GmbH). The time fish were able to withstand the water current was recorded for up to 3 h, when full recovery was assumed. Unlesioned fish always endured for 3 h. Lesioned fish showed gradual recovery between 1 and 6 weeks postlesion, in agreement with previous tests of recovery of unforced swimming behavior (Becker et al., 2004).

Reverse transcriptase PCR.

To assess the effect of cyclopamine on hh downstream genes spinal tissue was collected from the area of 3 mm surrounding the lesion site, and RNA was extracted (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen) from pooled tissue of at least 5 animals per treatment at 5 d postlesion from animals that had received a single cyclopamine or tomatidine injection at 4 d postlesion. Reverse transcription, using random primers (Promega), was performed with the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen). The following primers were used to amplify patched1 and olig2, normalized against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), by standard PCR (57°C, 27 cycles for olig2 and 30 cycles for patched1): GAPDH forward: 5′-ACTCCACTCATGGCCGTTAC-3′, GAPDH reverse: 5′-TCTTCTGTGTGGCGGTGTAG-3′, Olig2 forward: 5′-TCCAGCAGACCTTCTTCTCC-3′, Olig2 reverse: 5′-ACAACTGGACGGATGGAAACC-3′, patched1 forward: 5′-GTCTGCAAGCCACTTTTGATG C-3′, patched1 reverse: 5′-GGGGTAGCCATTGGGATAGT-3′.

To assess expression levels of FGF and retinoic acid pathway related genes, cDNA was prepared from unlesioned and lesioned (14 d postlesion) spinal cords in the same way as above. Standard PCR (35 cycles) was performed using primers and temperatures indicated in supplemental Table 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material.

Cell counts and statistical analysis.

Numbers of small motor neurons around the lesion site in Tg(hb9:gfp) fish were determined from stereological counts in confocal image stacks of three randomly selected vibratome sections from the region up to 750 μm rostral to the lesion site, and three sections from the region up to 750 μm caudal to the lesion site. Cell numbers were then calculated for the entire 1.5 mm surrounding the lesion site. PCNA+ cell profiles were counted in at least 6 randomly selected sections per animal from the same area by fluorescence microscopy. The observer was blinded to experimental treatments.

To estimate the increase in the number of ventricular cells expressing transcription factors after a lesion we counted labeled nuclear profiles in an optical section (0.4 μm in thickness), which showed clear labeling, within 750 μm rostral to caudal of the lesion site. Parenchymal cells were scored in a square area of 146 μm edge length, centered around the central canal.

Variability of values is given as SEM. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05) unless indicated differently.

Results

We aimed to elucidate the set of transcription factors that are expressed during motor neuron regeneration in the spinal cord of adult zebrafish and the signals that are active during regeneration using known developmental mechanisms as a starting point.

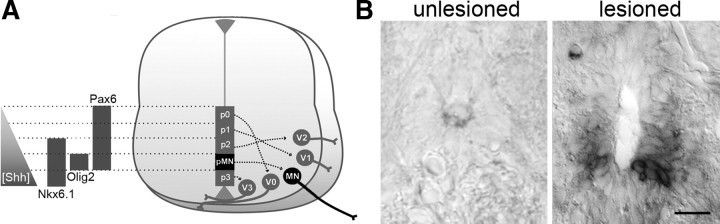

Expression of pMN transcription factors is retained in adult zebrafish and is increased after a spinal lesion

In the developing neural tube, motor neurons are derived from an olig2+, nkx6.1+, and pax6+ domain (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we analyzed expression of these genes in the adult spinal cord in the unlesioned and lesioned situation, focusing on the ventricular zone of Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells from which motor neurons regenerate (Reimer et al., 2008). We found that, generally, the ventricle increased massively in size close to the lesion site. The average circumference of the central canal in cross-section within 750 μm of the lesion site increased to almost 300% at 2 weeks postlesion (unlesioned: 33.4 ± 1.60, n = 7 animals; lesioned: 97.7 ± 10.50 μm, n = 7 animals; ANOVA, p = 0.0001) (Fig. 1B) and remained enlarged at 6 weeks postlesion (89.5 ± 7.91 μm, n = 7 animals; ANOVA, p = 0.0002). It has been found in the eel that widening of the central canal after spinal cord lesion directly correlates with an increase in the number of ventricular cells (Dervan and Roberts, 2003). Ventricular cells are potential stem cells and are the major proliferating cell type in the lesioned spinal cord (Reimer et al., 2008). Thus, a widened ventricle suggests an increase in symmetrical cell division of these cells that may lead to larger domains of progenitor cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of olig2 mRNA is increased in the lesioned adult spinal cord close to the lesion site at 2 weeks postlesion. A, Schematic presentation of transcription factor domains set up in the developing vertebrate neural tube by a ventrodorsal gradient of Shh (modified after Vallstedt and Kullander, 2007). Different progenitor zones (p0–3) give rise to distinct classes of interneurons (V0–3). The pMN zone gives rise to motor neurons (MN). B, Cross-sections through the adult spinal cord are shown at the level of the central canal (dorsal is up). Ventricular cells in ventrolateral positions around the central canal express detectable levels of olig2 mRNA in the lesioned spinal cord. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Using in situ hybridization for olig2 mRNA, we found that expression was undetectable in the unlesioned spinal cord. After a lesion, expression of olig2 mRNA was not detectable at 1 week postlesion. At 2 weeks postlesion, mRNA expression was strongly increased in the ependymal zone in a ventrolateral position, comparable to the relative position of developmental expression in the neural tube (Fig. 1A), in the vicinity of the lesion site (250 μm rostral and caudal to it) (Fig. 1B). Expression of olig2 mRNA was back to undetectable control levels at 6 weeks postlesion. Thus spatial and temporal regulation of olig2 coincided with the timing and location of motor neuron regeneration after a lesion, which also peaks close to the lesion site at 2 weeks postlesion (Reimer et al., 2008).

To determine the cell type that expresses olig2 mRNA, we used a Tg(olig2:egfp) transgenic fish. The transgene labels ependymoradial glial cells and oligodendrocytes in the unlesioned and lesioned spinal cord (Park et al., 2007; Reimer et al., 2008). The ventricular position of transgenic ependymoradial glial cells matched that of olig2 mRNA-expressing cells. The domain of Tg(olig2:egfp)+ cells at the ventricle was expanded in the vicinity of the lesion site by almost 80% (unlesioned: 10.3 ± 0.50 μm, n = 6 animals; lesioned: 18.0 ± 3.07 μm, n = 7 animals, p = 0.0183) (Fig. 2) at 2 weeks postlesion.

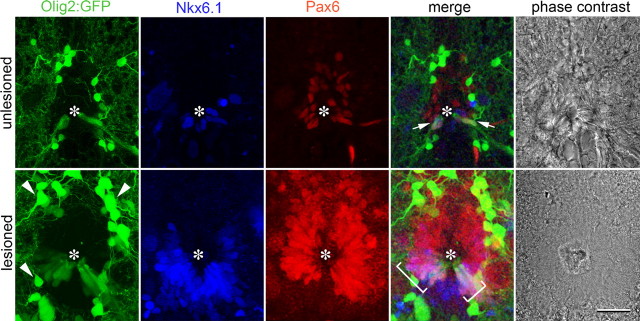

Figure 2.

Evidence for a pMN-equivalent zone in the ependymal layer of the adult spinal cord. Spinal cross-sections at the level of the central canal (asterisks) are shown. In the unlesioned (arrows) and lesioned spinal cord (brackets) Pax6/Tg(olig2:egfp)/Nkx6.1 coexpressing ependymoradial glial cells are present. Expression of all markers is increased close to a spinal lesion site at 2 weeks postlesion. Arrowheads, Oligodendrocytes. Scale bar, 20 μm.

While transgene expression closely matched that of the mRNA in the lesioned situation, only the transgene was detectable in ventrolateral ependymoradial glial cells in the unlesioned situation. We cannot exclude that the Tg(olig2:egfp) transgene expression in pMN-like cells in the unlesioned spinal cord is nonspecific. However, Tg(olig2:egfp) expression is precisely localized in the zone of Nkx6.1+/Pax6+ ependymoradial glial cells in the ventrolateral spinal cord (see below), and the transgene is driven by a large, reliable promoter region contained in a BAC clone (Shin et al., 2003). Thus it is possible that, by a cumulative effect of the highly stable GFP (Cubitt et al., 1995), the transgene may report levels of gene expression that were below the detection level of in situ hybridization. Thus a Tg(olig2:egfp) transgene is expressed in ventrolateral ependymoradial glial cells of the unlesioned spinal cord, and olig2 mRNA expression is clearly increased in that position in response to a lesion.

Nkx6.1 immunoreactivity was found in a U-shaped pattern in ventricular cells around the ventral central canal in unlesioned adult animals, which is reminiscent of the embryonic expression pattern in the neural tube. Some parenchymal cells were also Nkx6.1+. At 2 weeks after a spinal lesion, Nkx6.1 immunoreactivity was still detectable in a U-shape around the ventricle. However, more Nkx6.1+ ventricular cells were present and immunoreactivity was more intense. The number of ventricular Nkx6.1-immunoreactive nuclear profiles in single optical sections increased from 7.5 ± 1.45 profiles/section (n = 6 animals) to 35.3 ± 5.58 at 2 weeks postlesion (n = 6 animals, p = 0.0039). In the parenchyma, we observed 4.2 ± 0.83 cells in unlesioned animals and 6.3 ± 1.02 profiles/section in lesioned animals; p = 0.16). In multiple labeling experiments, we found that Nkx6.1 immunoreactivity overlapped with the Tg(olig2:egfp)+ zone of the adult ventricle and exceeded it slightly dorsally in the unlesioned and lesioned spinal cord (Fig. 2). Thus Nkx6.1 is expressed at low levels in the ventral ventricular zone of the unlesioned adult spinal cord, and its expression is increased in the same relative position after a lesion.

Pax6 immunoreactivity was detectable in an inverted U-shape around the ventricle and in some parenchymal cells in unlesioned animals. There was a ventral-high to dorsal-low gradient in Pax6 immunoreactivity. At 2 weeks postlesion this expression pattern was retained (Fig. 2). However, the number of ventricular Pax6-immunoreactive profiles in single optical sections strongly increased from 9.3 ± 2.19 profiles/section (n = 6 animals) to 43.5 ± 13.13 at 2 weeks postlesion (n = 6 animals, p = 0.0039). In the parenchyma, we observed 3.7 ± 0.80 profiles/section in unlesioned animals and 8.3 ± 1.15 profiles/section in lesioned animals (p = 0.0096), indicating a moderate increase in the number of parenchymal Pax6+ cells. Colabeling indicated that Pax6 immunoreactivity at the central canal overlapped with the Tg(olig2:egfp)+ zone and shared a ventral border with it in the unlesioned and lesioned spinal cord. Ventral Pax6 immunoreactivity also overlapped with dorsal Nkx6.1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 2). Thus, Pax6 expression in the laterodorsal aspect of the spinal cord is increased after a spinal lesion.

Overall, triple-labeling indicated that the motor neuron-generating Tg(olig2:egfp)+ zone was also Pax6+ and Nkx6.1+. Individual Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells were found to coexpress both Nkx6.1 and Pax6 in single optical sections of the unlesioned and lesioned spinal cord, and their number was increased from 2.0 ± 0.00 profiles/section in unlesioned animals (n = 2) to 13.7 ± 2.19 profiles/section at 2 weeks postlesion (n = 3 animals). Parenchymal cells were rarely found to coexpress Tg(olig2:egfp), Nkx6.1, and Pax6 (unlesioned: 0 profiles/section; lesioned: 0.3 ± 0.33 profiles/section). Thus a subset of ependymoradial glial cells in the adult spinal cord retain low, but clearly detectable, expression of markers for the pMN zone, namely Tg(olig2:egfp), Nkx6.1, and Pax6 in specific domains. The number of cells coexpressing these genes and gene expression levels are increased, when motor neurons are generated after a lesion (Reimer et al., 2008).

shha is upregulated in a distinct class of proliferating ependymoradial glial cells at the ventral midline of the spinal cord

To determine the possible signals that induce adult pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells to generate motor neurons we analyzed expression of shha. In the unlesioned adult spinal cord, there were very few cells contacting the central canal at the ventral midline that expressed shha mRNA, as detected by in situ hybridization. At 1 week postlesion, this pattern was unchanged. At 2 weeks postlesion, the area and labeling intensity of the signal at the ventral midline was strongly increased in a gradient with strongest expression in the immediate vicinity of the lesion site (Fig. 3A). At a distance of >1 mm rostral or caudal to the lesion site, labeling intensity was not different from unlesioned controls. At 6 weeks postlesion, labeling intensity was reduced again, but still higher than in unlesioned controls. This spatiotemporal expression pattern is similar to that of olig2 mRNA (see above) and the spatiotemporal distribution of motor neuron regeneration (Reimer et al., 2008).

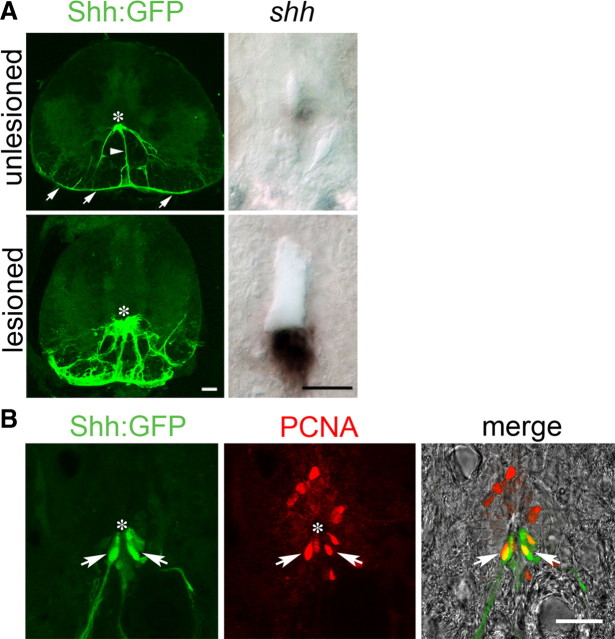

Figure 3.

Increased expression of shha and proliferation of Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells in the ventricular zone of the lesioned spinal cord. Cross-sections are shown of whole spinal cross-sections (Tg(shha:gfp) in A only) or just for the area around in the ventricle at high magnification (all other images). Asterisks indicate the position of the ventricle. A, Expression of shha mRNA is increased in the ventral-most position of the ventricle and Tg(shha:gfp)+ ventral ependymoradial glial cells, which form part of the glial limitans (arrows), are more numerous at 2 weeks postlesion. B, Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells actively proliferate at 2 weeks postlesion, as indicated by double labeling with PCNA antibodies (arrows). Scale bars, 25 μm.

To determine which cell type expressed shha we analyzed transgenic fish, in which expression of GFP is under the control of the shha promoter. In unlesioned animals, a few ependymoradial glial cells at the ventral midline of the spinal cord expressed GFP. These cells had cell bodies contacting the ventricle, and their radial processes could be followed to the pial surface where their endfeet formed an uninterrupted ventral part of the glial limitans. At 2 weeks postlesion, these cells increased in number and still formed the glial limitans (Fig. 3A). Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells were proliferating at 2 weeks postlesion as indicated by double-labeling with an antibody to PCNA, which labels cells in early G1 phase and S phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 3B).

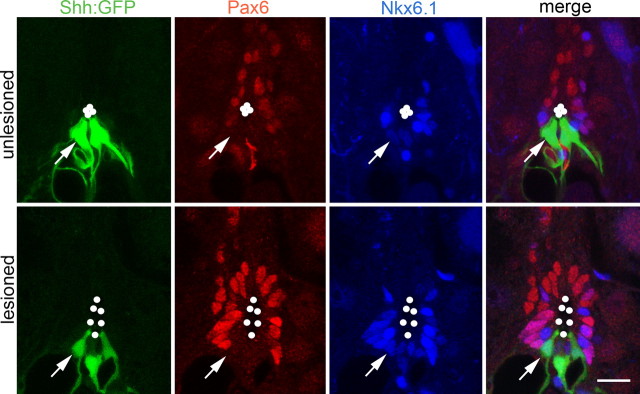

Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells were distinct from Tg(olig2:egfp)+ motor neuron progenitor cells, as revealed in multiple labeling experiments. Pax6 immunoreactivity bordered ventrally on Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells in the unlesioned and lesioned spinal cord (Fig. 4). Tg(shha:gfp)+/Pax6+ cells were not detected, in contrast to Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells, which expressed Pax6 (Fig. 2). The fact that the ventral border of Pax6 expression in ventricular cells is coextensive with that of Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells indicates that pMN-like cells line the central canal immediately adjacent to the shha-expressing cells. In summary, in situ hybridization and analysis of transgene expression indicated that in the lesioned adult spinal cord shha expression was increased by proliferating ventral ependymoradial glial cells, directly adjacent to motor neuron progenitor cells.

Figure 4.

Tg(shha:gfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells coexpress Nkx6.1, but not Pax6. Spinal cross-sections at the level of the central canal (outlined by dots) are shown. Arrows point to an individual Tg(shha:gfp)+/Nkx6.1+/Pax6− cell. Scale bar, 15 μm.

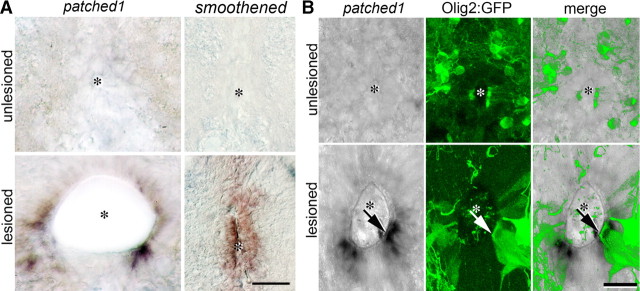

Expression patterns of hh receptors suggests lesion-induced activity of the pathway in motor neuron progenitor cells

If hh signaling is active in the adult lesioned spinal cord, the patched1 receptor and target gene as well as smoothened as coreceptor should be expressed. In situ hybridization indicated that smoothened mRNA was undetectable in the unlesioned spinal cord. We found increased expression of smoothened mRNA along the entire dorsoventral extent of the ventricular zone of the lesioned spinal cord in a proximodistal gradient that was strongest close to the lesion site at 2 weeks postlesion (Fig. 5A). At a distance of >1 mm rostral and caudal to the lesion site no enhanced smoothened expression was detectable. This matches the proximodistal expression gradient of shha.

Figure 5.

hh pathway genes are upregulated in ependymal cells of the lesioned spinal cord. Cross-sections of the adult spinal cord at the level of the central canal (asterisk) are shown. A, Expression of patched1 and smoothened mRNA is increased after a lesion. Note polarized (stronger ventral) expression of patched1 mRNA, whereas smoothened mRNA is detectable along the dorsoventral extent of the central canal of the lesioned spinal cord. B, In the lesioned, but not the unlesioned spinal cord, Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells express detectable levels of mRNA for patched1 (arrow), an indicator of hh pathway activity. Scale bars: A, 25 μm; B, 15 μm.

Patched1 mRNA expression was likewise increased from undetectable levels close to the lesion site at 2 weeks postlesion. However, the pattern of expression differed from that of smoothened. The ventral zone, corresponding to the cells that express shha, was free of signal. In the adjacent zone there was strong expression of patched1 mRNA that tapered off toward the dorsal spinal cord (Fig. 5A). Since strong expression of patched1 is an indicator of activity of the hh pathway, we determined whether Tg(olig2:egfp)+ motor neuron progenitors expressed patched1, using double labeling of patched1 mRNA in lesioned Tg(olig2:egfp) transgenic fish at 2 weeks postlesion. The region of strongest patched1 mRNA expression overlapped with Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells, consistent with the hypothesis that Shh-dependent transcription took place in Tg(olig2:egfp)+ motor neuron progenitor cells after a lesion (Fig. 5B).

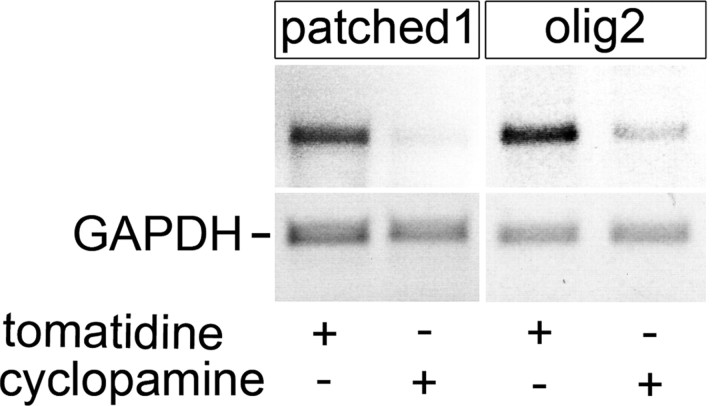

Blocking hh signaling attenuates motor neuron regeneration and proliferation of ventricular cells

To determine whether Shh might influence motor neuron regeneration we blocked hh pathway activity by intraperitoneal injections of the specific inhibitor cyclopamine. Injection of cyclopamine led to a specific reduction in expression of patched1 and olig2 mRNA in the lesioned spinal cord relative to the constitutively expressed gene GAPDH at 24 h after the injection, as detected by PCR analysis of the lesioned spinal cord. This indicates that intraperitoneal injections of cyclopamine can indeed reduce expression of Shh target genes in the lesioned spinal cord (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Expression of patched1 and olig2 mRNA in the adult lesioned spinal cord is specifically reduced by intraperitoneal cyclopamine injection. PCR amplification of patched1 and olig2, using GAPDH as a standard, is shown. Tomatidine injection is used as a negative control.

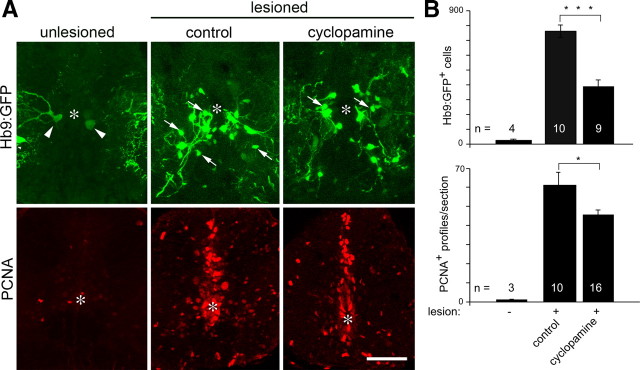

To determine whether cyclopamine treatment would influence motor neuron regeneration, we used the Tg(hb9:gfp) transgenic fish, because newly generated motor neurons can be readily discriminated by transgene expression and their small size (<12 μm diameter) in lesioned animals (Reimer et al., 2008), thus obviating the need for BrdU labeling in this analysis. The accuracy of transgenic labeling of newly generated motor neurons has previously been confirmed by Hb9 and Islet-1/-2 immunohistochemistry (Reimer et al., 2008). Analysis took place at 2 weeks postlesion, when motor neuron regeneration peaks. Repeated cyclopamine injections (see methods) caused a highly significant 50% reduction in the number of newly generated Tg(hb9:gfp)+ motor neurons within 1.5 mm surrounding the lesion site (377 ± 45.7 cells/animal; n = 9 animals) compared with animals injected with the related, but ineffective substance tomatidine (747 ± 42.2 cells/animal; n = 10 animals; p = 0.0004) (Fig. 7A,B) in stereological counts. In unlesioned animals, the number of small Tg(hb9:gfp)+ motor neurons is very low (20 ± 7.7 cells/animal) (Fig. 7) (Reimer et al., 2008). This suggests that hh signaling is necessary for efficient motor neuron regeneration.

Figure 7.

Cyclopamine treatment impairs motor neuron regeneration. A, Spinal cross-sections are shown. Asterisks indicate the central canal. Cyclopamine injection reduces the number of newly generated motor neurons (Tg(hb9:gfp)+; arrows) and proliferating cells in the ventricular zone (PCNA+). Arrowheads indicate large motor neurons in unlesioned animals. B, Quantification of reduced numbers of small, newly generated Tg(hb9:gfp)+ motor neurons and PCNA+ profiles depicted in A. Values for unlesioned animals are given for reference (Reimer et al., 2008). Control, Injected with tomatidine. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Since Shh is a mitogen (Jessell, 2000; Fuccillo et al., 2006), we tested whether cyclopamine would attenuate proliferation in the lesioned spinal cord. In the unlesioned spinal cord, proliferation is very low (Fig. 7). Lesion-induced proliferation occurs mostly at the ventricle, peaks at 2 weeks postlesion and can be detected using PCNA antibodies (Reimer et al., 2008). Indeed, the number of PCNA+ cell profiles in the ventricular zone of cyclopamine-injected animals (45 ± 2.8 profiles/section; n = 16 animals) was significantly reduced by 25% compared with tomatidine-injected control animals (60 ± 7.0 profiles/section; n = 10 animals; p = 0.027; one-tailed test) (Fig. 7A,B) at 2 weeks postlesion. This indicates that proliferation of progenitor cells at the ventricle depends at least in part on hh signaling.

Attenuation of motor neuron regeneration does not impair functional recovery or axon regrowth from the brainstem

The possibility to reduce motor neuron regeneration around a spinal lesion with cyclopamine afforded the opportunity to test whether these neurons contribute to recovery of swimming behavior. We performed a test of swimming performance at 6 weeks postlesion, when functional recovery plateaus (Becker et al., 2004). We adapted an endurance test in which fish swim against a constant water current (van Raamsdonk et al., 1998). Cylopamine-injected animals reached a mean endurance of 77 min ± 36.3 min (n = 15 animals), whereas tomatidine-injected animals reached 80 ± 36.6 min (n = 20 animals) at 6 weeks postlesion (from less that 15 s for both groups at 7 d postlesion). While both experimental groups showed significant improvement of endurance over time (ANOVA, p < 0.0001), the slightly lower endurance in cyclopamine-treated fish was not statistically significant compared with control treatment (p = 0.72). Another test in which the distance swum by freely moving fish within a given time frame (Becker et al., 2004) did also not yield significant differences between tomatidine and cyclopamine-treated animals (data not shown).

We tested whether cyclopamine injections would influence axon regrowth from the brainstem, which is essential for functional recovery (Becker et al., 2004). The number of supraspinal neurons that grew an axon beyond the spinal lesion site at 6 weeks postlesion was also not significantly impaired by cyclopamine injections (cyclopamine: 58 ± 10.0 neurons, n = 3; control: 66.6 ± 8.5 neurons, n = 9, p = 0.52). Thus a 50% reduction of motor neuron regeneration around a spinal lesion site by cyclopamine did not detectably impair functional recovery or regrowth of axons from the brainstem.

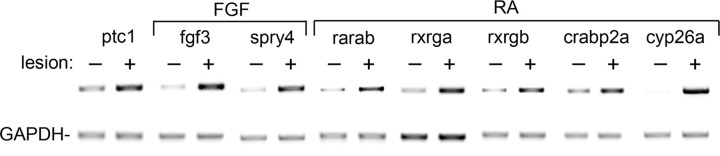

Genes indicating FGF and retinoic acid pathway activity show increased expression in the lesioned spinal cord

Cyclopamine treatment did not completely inhibit motor neuron regeneration. This suggests involvement of other signaling pathways in adult motor neuron regeneration. To elucidate such signals we analyzed the expression of indicator genes for the retinoic acid and FGF pathways in the adult regenerating spinal cord, because these signaling pathways are known to play a role during embryonic motor neuron generation (Novitch et al., 2003). For the FGF pathway we found that mRNA expression of fgf3 and the downstream gene sprouty4 (spry4) was robustly increased in the lesioned spinal cord (Fig. 8). Other signals (fgf8, fgf17b), receptors (fgfr1a, fgfr2, fgfr3, fgfr4) and downstream genes (dusp6, pea3, spry1, spry2) showed little or no upregulation (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). For the retinoic acid pathway we detected a robust increase in mRNA levels of retinoic acid receptor subunits (rarab, rxrga, rxrgb) and downstream genes (crapb2a, cyp26a) (Fig. 8). The retinoic acid synthesizing enzyme raldh2, as well as other receptor subunits (raraa, rarga, rargb, rxraa) and the downstream gene crabp2b showed little or no increase in mRNA expression (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These findings suggest that FGF and retinoic acid signaling could also be involved in motor neuron regeneration.

Figure 8.

FGF and retinoic acid signaling pathway related genes show increased expression in the lesioned adult spinal cord. PCR analyses of unlesioned and lesioned (14 d postlesion) spinal cord, using GAPDH levels as a standard, are shown. All indicated genes show robust upregulation in lesioned tissue. Patched1 (ptc1) as an indicator for Shh pathway activity is included as a positive control.

Discussion

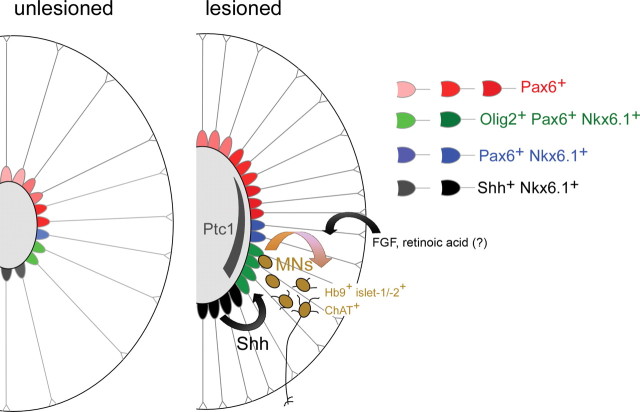

In this study we demonstrate for the first time that the myelinated, fully adult spinal cord of zebrafish contains a subpopulation of ependymoradial glial cells that retain transcription factor expression of the embryonic pMN zone. We provide evidence that these cells, similar to their embryonic counterparts, react to an Shh signal from the ventral spinal cord with motor neuron production after a spinal lesion (summarized in Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Summary of known events associated with motor neuron regeneration in adult zebrafish. Schematic cross-sections through the spinal cord are shown (the central canal is represented by a gray oval). Different ependymoradial glial cells in the unlesioned spinal cord express low levels (light shading) of different transcription factor combinations found in similar dorsoventral positions in the embryonic neural tube. After a lesion, the central canal widens close to the lesion site, concomitant with an increase in numbers of ependymoradial glial cells that also express higher levels of transcription factors (darker shading). A ventrodorsal hh signal, evidenced by a ventrodorsal patched1 (ptc1) mRNA expression gradient in ependymoradial glial cells, contributes to production of Hb9+/islet-1/-2+/ChAT+ motor neurons (MNs) from pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells (green) after a lesion. Increased expression of genes related to FGF and retinoic acid signaling suggests involvement of these signals in motor neuron regeneration.

Evidence for a role of Shh in motor neuron regeneration

Upregulation of patched1 in pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells may indicate lesion-induced activity of Shh signaling in these cells. This is because patched1 is not only a receptor, but also a target gene of the hh pathway, thus reporting activity of the pathway (Concordet et al., 1996; Machold et al., 2003). Indeed, patched1 shows a clear gradient from ventral-strong to dorsal-weak expression, with strongest expression in pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells, which are closest to the source of shha expression. In contrast, smoothened, which is also necessary for hh signaling, but not a direct target of the pathway, is uniformly expressed in ependymoradial glial cells along the dorsoventral axis of the lesioned spinal cord.

Inhibition of hh signaling with cyclopamine indicates that the pathway plays a major role in motor neuron regeneration. Blocking the signal with cyclopamine in vivo reduced motor neuron regeneration by 50%. The fact that ventricular cell division was also reduced suggests that Shh may act at the level of cell division in pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells. However, effects on the acquisition of a motor neuron fate by postmitotic cells or the survival of these cells cannot be excluded.

Cyclopamine effects are probably specific, since PCR results indicated a selective and strong reduction in patched1 and olig2 mRNA expression after cyclopamine injection. Moreover, functional recovery and the number of axons that regenerated from the brainstem were not affected, suggesting the absence of global toxic effects of cyclopamine.

Why was behavior not influenced by cyclopamine treatment? Regenerated, ChAT+ mature motor neurons partially replace the population of previously existing motor neurons that are lost around a spinal lesion site (Reimer et al., 2008). However, while motor neuron regeneration was reduced by 50%, an average of 377 new motor neurons remained, which is still in excess of the ∼120 motor neurons that eventually show signs of full integration into the spinal network (Reimer et al., 2008). It is also possible that motor neuron regeneration around a spinal lesion site is not necessary for overall functional recovery. Interestingly, the fact that regeneration of axons from the brainstem was also unaffected, speaks against the idea that newly generated motor neurons exert a major trophic or tropic influence on these axons.

Involvement of developmental signaling pathways in adult motor neuron regeneration

The remaining motor neuron generation after cyclopamine treatment may be attributable to other pathways that promote motor neuron regeneration. Our analysis indicates increased expression of fgf3 and its target gene spry4 (Fürthauer et al., 2001), as well as several retinoic acid related genes (Maden, 2006). These include the target gene crabp2a, which, for example, is active in motor neurons derived form embryonic stem cells in vitro (Chaerkady et al., 2009). Thus, our data are consistent with an involvement of additional embryonic signals, FGF and retinoic acid, in adult motor neuron regeneration. Together with the role of Shh and upregulation of embryonic transcription factors Pax6, olig2, and Nkx6.1 this suggests that embryonic signaling pathways are at least partially redeployed during motor neuron regeneration. In contrast, during adult heart regeneration in zebrafish, transcription factors active during heart development (nkx2.5, tbx5) are not upregulated, whereas other genes (msxB, msxC, deltaC, notch1b) are expressed only in the regenerating heart (Raya et al., 2003).

Is there a lesion-induced switch in pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells for motor neuron generation?

Given that many pMN transcription factors and the shha signal are detectable at low levels also in the unlesioned spinal cord, one may speculate that a lesion simply augments a normal program of adult motor neuron generation. However, ventricular proliferation and motor neuron generation is extremely rare in the unlesioned spinal cord (one new BrdU+ motor neuron in one fish was observed in a sample of 14 adult fish; Reimer et al., 2008). Only after a lesion, there is massive motor neuron generation (200 new BrdU+ motor neurons within 1.5 mm around a spinal lesion site per fish). Moreover, genes necessary for hh pathway activity, patched1 and smoothened (Chen et al., 2001) only become detectable in the lesioned spinal cord by in situ hybridization. Finally, a hh agonist alone failed to elicit motor neuron generation or ventricular proliferation in the unlesioned spinal cord (own unpublished observations). This suggests that additional lesion-induced changes are necessary to switch pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells to motor neuron generation.

pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells may be multipotent progenitor cells

pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells are located in the Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ventricular zone of the spinal cord and increase in number after a lesion. Likewise, the ventricular zone of Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells is enlarged after a lesion, and these cells incorporate BrdU and are labeled by PCNA antibodies (Reimer et al., 2008). This suggests that the ependymoradial glial cell populations expand after a lesion, presumably by symmetric cell divisions. This may result in the significant widening of the central canal during regeneration, also observed in other teleost species (Dervan and Roberts, 2003). We have shown previously by lineage tracing that Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial cells give rise to Hb9+ motor neurons in the lesioned spinal cord (Reimer et al., 2008). It has been suggested that Tg(olig2:egfp)+ ependymoradial glial give rise to oligodendrocytes in the unlesioned spinal cord (Park et al., 2007). Thus pMN-like ependymoradial glial cells are probably multipotent progenitor cells, giving rise to themselves, motor neurons, and oligodendrocytes. In contrast, mammalian forebrain ependymal cells, which produce glial cells and neuroblasts after a stroke lesion, fail to maintain their population by self-renewal (Carlén et al., 2009).

Adult ependymoradial glial cells may be the equivalent of embryonic neural tube progenitor cells

In the unlesioned adult spinal cord, we find expression of key defining factors of progenitor and signaling zones of the embryonic neural tube, shha, Pax6, Nkx6.1, and an Tg(olig2:egfp) transgene in almost identical, partially overlapping relative positions around the central canal as in the developing neural tube (Varjosalo and Taipale, 2008). Similarly, the dorsal neural tube marker pax7 is expressed in the dorsal spinal cord of the adult axolotl (Schnapp et al., 2005). Similar to progenitor cells in the developing neural tube, adult ependymoradial glial cells contact the ventricle and the pial surface. For these reasons it is tempting to speculate that during the developmental thickening of the wall of the neural tube, these cells simply retain contact with the pial and ventricular surfaces together with their progenitor zone-specific expression profile of transcription factors. In such a scenario, the ventral shha-expressing ependymoradial glial cells would be cells that originally formed the floor plate of the embryonic neural tube.

Do similar progenitor cells exist in the adult mammalian spinal cord?

It has been shown that stem cells exist in the adult mammalian spinal cord that can form neurospheres in vitro and neurons in vivo, when transplanted into a favorable environment (Shihabuddin et al., 2000). Notably, lineage tracing experiments indicate that ependymal cells are the main neurosphere forming cell population in the lesioned mouse spinal cord. These ependymal cells self-renew and generate scar-forming cells as well as oligodendrocytes after a lesion. They form part of the spinal cord ependyma and possess long radial processes, similar to ependymoradial glial cells in zebrafish. However, processes do not reach the pial surface, but form endfeet on blood vessels (Meletis et al., 2008).

Our observations in adult fish raise the question whether adult mammalian spinal ependymal cells possess any dorsoventral polarity, which might predispose them for the generation of specific neuronal cell types. Pax6, but not Olig2 or Nkx2.2, becomes detectable in the ependyma of the injured rat spinal cord. However, it is unclear whether this expression is polarized (Yamamoto et al., 2001). One report (Chen et al., 2005) showed a surprisingly widespread increase in shh mRNA expression in the entire ependyma and several parenchymal cell types in mice. Interestingly, administering Shh or a hh agonist leads to ventricular proliferation and nestin expression in the lesioned spinal cord of adult rats (Bambakidis et al., 2003; Bambakidis et al., 2009), suggesting that mammalian spinal ependymal cells may also be capable of reacting to a hh signal. In the lesioned mammalian cortex astrocytes upregulate shh expression, which regulates proliferation of olig2+ precursor cells (Amankulor et al., 2009).

Conclusions

Ependymoradial glial cells in the spinal cord of adult zebrafish share morphological and molecular features with presumptive mammalian spinal stem cells. Our spinal lesion paradigm in zebrafish may thus be useful as a pharmacologically and genetically accessible model to determine the signals that allow motor neuron regeneration in the spinal cord of a fully adult vertebrate. Shh may be such a signal, as it is necessary for a pMN-like subpopulation of ependymoradial glial cells to efficiently produce motor neurons in the lesioned spinal cord of adult zebrafish.

Footnotes

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (T.B.), the Wellcome Trust (C.G.B.), an ERASMUS grant (M.K.), the Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins University and the Euan MacDonald Centre for Motor Neurone Disease Research (C.G.B.), Tenovus Scotland, and the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine of the University of Edinburgh (V.K., T.B.). We thank Drs. B. Appel, C. Neumann, Z. Varga and U. Strähle for transgenic fish and probes, Drs. O. Madsen and V. van Heyningen for antibodies, Dr. P. Brophy for support and helpful discussions, Dr. M. Schachner for helpful discussions, Dr. D. Lyons for critically reading the manuscript, Dr. T. Gillespie for help with the confocal microscopy and G. Muirhead for technical assistance. Some of this work is part of the Diploma thesis of I.S., performed at the Zentrum für Molekulare Neurobiologie, Hamburg.

References

- Amankulor NM, Hambardzumyan D, Pyonteck SM, Becher OJ, Joyce JA, Holland EC. Sonic hedgehog pathway activation is induced by acute brain injury and regulated by injury-related inflammation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10299–10308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2500-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avaron F, Hoffman L, Guay D, Akimenko MA. Characterization of two new zebrafish members of the hedgehog family: atypical expression of a zebrafish Indian hedgehog gene in skeletal elements of both endochondral and dermal origins. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:478–489. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambakidis NC, Wang RZ, Franic L, Miller RH. Sonic hedgehog-induced neural precursor proliferation after adult rodent spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:70–75. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.1.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambakidis NC, Horn EM, Nakaji P, Theodore N, Bless E, Dellovade T, Ma C, Wang X, Preul MC, Coons SW, Spetzler RF, Sonntag VK. Endogenous stem cell proliferation induced by intravenous hedgehog agonist administration after contusion in the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10:171–176. doi: 10.3171/2008.10.SPI08231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareyre FM. Neuronal repair and replacement in spinal cord injury. J Neurol Sci. 2008;265:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CG, Lieberoth BC, Morellini F, Feldner J, Becker T, Schachner M. L1.1 is involved in spinal cord regeneration in adult zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7837–7842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2420-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Wullimann MF, Becker CG, Bernhardt RR, Schachner M. Axonal regrowth after spinal cord transection in adult zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:577–595. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970127)377:4<577::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlén M, Meletis K, Göritz C, Darsalia V, Evergren E, Tanigaki K, Amendola M, Barnabé-Heider F, Yeung MS, Naldini L, Honjo T, Kokaia Z, Shupliakov O, Cassidy RM, Lindvall O, Frisén J. Forebrain ependymal cells are Notch-dependent and generate neuroblasts and astrocytes after stroke. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:259–267. doi: 10.1038/nn.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaerkady R, Kerr CL, Marimuthu A, Kelkar DS, Kashyap MK, Gucek M, Gearhart JD, Pandey A. Temporal analysis of neural differentiation using quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1315–1326. doi: 10.1021/pr8006667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman SE, Layden MJ, Von Ohlen T, Doe CQ, Eisen JS. Zebrafish and fly Nkx6 proteins have similar CNS expression patterns and regulate motoneuron formation. Development. 2004;131:5221–5232. doi: 10.1242/dev.01397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Leong SY, Schachner M. Differential expression of cell fate determinants in neurons and glial cells of adult mouse spinal cord after compression injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1895–1906. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Burgess S, Hopkins N. Analysis of the zebrafish smoothened mutant reveals conserved and divergent functions of hedgehog activity. Development. 2001;128:2385–2396. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concordet JP, Lewis KE, Moore JW, Goodrich LV, Johnson RL, Scott MP, Ingham PW. Spatial regulation of a zebrafish patched homologue reflects the roles of sonic hedgehog and protein kinase A in neural tube and somite patterning. Development. 1996;122:2835–2846. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt AB, Heim R, Adams SR, Boyd AE, Gross LA, Tsien RY. Understanding, improving and using green fluorescent proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie PD, Ingham PW. Induction of a specific muscle cell type by a hedgehog-like protein in zebrafish. Nature. 1996;382:452–455. doi: 10.1038/382452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervan AG, Roberts BL. Reaction of spinal cord central canal cells to cord transection and their contribution to cord regeneration. J Comp Neurol. 2003;458:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E, McMahon AP, Briscoe J. Pattern formation in the vertebrate neural tube: a sonic hedgehog morphogen-regulated transcriptional network. Development. 2008;135:2489–2503. doi: 10.1242/dev.009324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan-Steet H, Fox MA, Meyer D, Sanes JR. Neuromuscular synapses can form in vivo by incorporation of initially aneural postsynaptic specializations. Development. 2005;132:4471–4481. doi: 10.1242/dev.02044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuccillo M, Joyner AL, Fishell G. Morphogen to mitogen: the multiple roles of hedgehog signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:772–783. doi: 10.1038/nrn1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürthauer M, Reifers F, Brand M, Thisse B, Thisse C. sprouty4 acts in vivo as a feedback-induced antagonist of FGF signaling in zebrafish. Development. 2001;128:2175–2186. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3059–3087. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell TM. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:20–29. doi: 10.1038/35049541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsche W. Die regenerativen Vorgänge am Rückenmark erwachsener Teleostier nach operativer Kontinuitätstrennung. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch. 1950;77:313–406. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss S, Concordet JP, Ingham PW. A functionally conserved homolog of the Drosophila segment polarity gene hh is expressed in tissues with polarizing activity in zebrafish embryos. Cell. 1993;75:1431–1444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K, Kaspar BK, Gage FH, Schaffer DV. Sonic hedgehog regulates adult neural progenitor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:21–27. doi: 10.1038/nn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberoth BC, Becker CG, Becker T. Double labeling of neurons by retrograde axonal tracing and non-radioactive in situ hybridization in the CNS of adult zebrafish. Methods Cell Sci. 2003;25:65–70. doi: 10.1023/B:MICS.0000006848.57869.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machold R, Hayashi S, Rutlin M, Muzumdar MD, Nery S, Corbin JG, Gritli-Linde A, Dellovade T, Porter JA, Rubin LL, Dudek H, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron. 2003;39:937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maden M. Retinoids and spinal cord development. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:726–738. doi: 10.1002/neu.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meletis K, Barnabé-Heider F, Carlén M, Evergren E, Tomilin N, Shupliakov O, Frisén J. Spinal cord injury reveals multilineage differentiation of ependymal cells. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovic J, Götz M. Signaling in adult neurogenesis: from stem cell niche to neuronal networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch BG, Wichterle H, Jessell TM, Sockanathan S. A requirement for retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional activation in ventral neural patterning and motor neuron specification. Neuron. 2003;40:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohori Y, Yamamoto S, Nagao M, Sugimori M, Yamamoto N, Nakamura K, Nakafuku M. Growth factor treatment and genetic manipulation stimulate neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis by endogenous neural progenitors in the injured adult spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11948–11960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3127-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Mehta A, Richardson JS, Appel B. olig2 is required for zebrafish primary motor neuron and oligodendrocyte development. Dev Biol. 2002;248:356–368. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Shin J, Appel B. Spatial and temporal regulation of ventral spinal cord precursor specification by Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2004;131:5959–5969. doi: 10.1242/dev.01456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Shin J, Roberts RK, Appel B. An olig2 reporter gene marks oligodendrocyte precursors in the postembryonic spinal cord of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3402–3407. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raya A, Koth CM, Buscher D, Kawakami Y, Itoh T, Raya RM, Sternik G, Tsai HJ, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Izpisua-Belmonte JC. Activation of Notch signaling pathway precedes heart regeneration in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11889–11895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834204100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer MM, Sörensen I, Kuscha V, Frank RE, Liu C, Becker CG, Becker T. Motor neuron regeneration in adult zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8510–8516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P, Ruiz i Altaba A. In vivo inhibition of endogenous brain tumors through systemic interference of Hedgehog signaling in mice. Mech Dev. 2005;122:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp E, Kragl M, Rubin L, Tanaka EM. Hedgehog signaling controls dorsoventral patterning, blastema cell proliferation and cartilage induction during axolotl tail regeneration. Development. 2005;132:3243–3253. doi: 10.1242/dev.01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihabuddin LS, Horner PJ, Ray J, Gage FH. Adult spinal cord stem cells generate neurons after transplantation in the adult dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8727–8735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08727.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Park HC, Topczewska JM, Mawdsley DJ, Appel B. Neural cell fate analysis in zebrafish using olig2 BAC transgenics. Methods Cell Sci. 2003;25:7–14. doi: 10.1023/B:MICS.0000006847.09037.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkumatava A, Fischer S, Müller F, Strähle U, Neumann CJ. Sonic hedgehog, secreted by amacrine cells, acts as a short-range signal to direct differentiation and lamination in the zebrafish retina. Development. 2004;131:3849–3858. doi: 10.1242/dev.01247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallstedt A, Kullander K, editors. Genetic approaches to spinal locomotor function in mammals. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van Raamsdonk W, Maslam S, de Jong DH, Smit-Onel MJ, Velzing E. Long term effects of spinal cord transection in zebrafish: swimming performances, and metabolic properties of the neuromuscular system. Acta Histochem. 1998;100:117–131. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(98)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga ZM, Amores A, Lewis KE, Yan YL, Postlethwait JH, Eisen JS, Westerfield M. Zebrafish smoothened functions in ventral neural tube specification and axon tract formation. Development. 2001;128:3497–3509. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varjosalo M, Taipale J. Hedgehog: functions and mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2454–2472. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon; 1989. The zebrafish book: a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Nagao M, Sugimori M, Kosako H, Nakatomi H, Yamamoto N, Takebayashi H, Nabeshima Y, Kitamura T, Weinmaster G, Nakamura K, Nakafuku M. Transcription factor expression and Notch-dependent regulation of neural progenitors in the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9814–9823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09814.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]