Abstract

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is common and bacteremia complicating this infection is frequently seen. There has been limited data published that characterize bacteremic UTI in a population-based setting over an extended period. We therefore examined the incidence rate, microbiology, outcome, and in vitro antimicrobial resistance trends of bacteremic UTI due to gram-negative bacilli in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1/1/1998 to 12/31/2007.

Methods

We used Kaplan-Meier method to estimate mortality rates, Cox proportional hazard regression to determine risk factors for mortality, and logistic regression to examine temporal changes in antimicrobial resistance rates.

Results

We identified 542 episodes of bacteremic gram-negative UTI among Olmsted County residents during the study period. The median age of patients was 71 years and 65.1% were females. The age-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000 person-years was 55.3 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 49.5–61.2) in females and 44.6 (95% CI: 38.1–51.1) in males. Escherichia coli was the most common pathogen (74.9%). The 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates were 4.9% (95% CI: 3.0–6.8) and 15.6% (95% CI: 12.4–18.8), respectively. Older age was associated with higher mortality; community-acquired infection acquisition and E. coli UTI were both independently associated with lower mortality. During the study period, resistance rates increased linearly from 10% to 24% for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and from 1% to 8% for ciprofloxacin.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study of bacteremic gram-negative UTI. The linear trend of increasing antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative isolates should be considered when empiric therapy is selected.

Keywords: gram-negative, bloodstream infection, urinary tract infection, epidemiology, mortality, antimicrobial resistance, fluoroquinolones, incidence

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common bacterial infections in the general population, with an estimated overall incidence rate of 17.5 per 1000 person-years.1 Gram-negative bacilli cause the overwhelming majority of UTIs.1–4 It has been estimated that up to 15% of patients with UTI are bacteremic at the time of presentation.5 To our knowledge, bacteremic UTI has not been evaluated in a population-based setting. Therefore, we designed a population-based study to examine the epidemiology, microbiology, outcome, and in vitro antimicrobial resistance trends of bacteremic UTI caused by gram-negative bacilli in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over a 10-year period. The aims of the study were to: (i) determine the age, gender, and calendar year trends in the incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI; (ii) examine the microbiology of bacteremic gram-negative UTI by age group and gender; (iii) determine the 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates following bacteremic gram-negative UTI and identify the risk factors for mortality; (iv) examine the in vitro antimicrobial resistance trends of gram-negative isolates to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and ceftazidime during the study period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

Olmsted County is located in southeastern Minnesota with a population of 124,277 according to the 2000 census.6 With the exception of a lower prevalence of injection drug use, a higher prevalence of middle-class individuals and a higher proportion being employed in the healthcare industry, the population characteristics of Olmsted County residents are similar to those of USA non-Hispanic whites.7,8 The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a unique medical records-linkage system that encompasses care delivered to residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. The microbiology laboratories at Mayo Medical Center and Olmsted Medical Center are the only two laboratories in Olmsted County. These two medical centers are geographically isolated from other urban centers as previously described;7, 9, 10 therefore, local residents are able to obtain healthcare within the community, rather than seeking healthcare at a distant geographic location.

Case ascertainment

We used complete enumeration of Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1 January 1998 to 31 December 2007. Using the microbiology databases at the Mayo Medical Center Rochester and Olmsted Medical Center, the only two medical centers in Olmsted County, we identified 542 episodes (492 first episodes and 50 recurrent episodes) of monomicrobial bacteremic gram-negative UTI among Olmsted County residents within the study period. Medical records were reviewed by the primary investigator (M.N.A.) to confirm the diagnosis and determine patient residency status. The following variables were collected: age, gender, date of UTI, causative organism, site of infection acquisition, date of last follow-up, outcome at last follow-up, and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility data. Death was confirmed by reviewing medical records and Minnesota death registry database.

Blood and urine cultures were identified using standard microbiology techniques according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The microbiology laboratories at the Mayo Medical Center Rochester and Olmsted Medical Center are certified by the College of American Pathologists. CLSI methods were employed to evaluate in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility results of gram-negative isolates. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both institutions. The detailed case ascertainment and culture methods used were described elsewhere.10, 11

Case definition

Bacteremic gram-negative UTI was defined as the monomicrobial growth of any aerobic gram-negative bacillus in a blood culture and one of the following: (i) signs and symptoms of UTI such as fever, dysuria, frequency of micturition, back or flank pain, or costovertebral angle tenderness, (ii) pyuria, (iii) growth of the same gram-negative bacillus in a urine culture in the absence of other identifiable sources of bacteremia. Monomicrobial gram-negative bacteremia was defined as growth of only one gram-negative bacillus in a blood culture, excluding coagulase-negative staphylococci, Corynebacterium species, and Propionibacterium spp. A first episode of bacteremic gram-negative UTI was defined as the initial episode of bacteremic gram-negative UTI in a particular patient during the study period. Recurrent bacteremic gram-negative UTI was defined as the occurrence of a subsequent episode of bacteremic gram-negative UTI during the study period at least one week after resolution of a previous episode. Cases were classified according to the site of acquisition into nosocomial, healthcare-associated, and community-acquired.12

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data: medians and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate associations between categorical variables and Wicoxon rank-sum test was used to test for differences in medians across continuous variables.

The incidence rate, expressed as the number of all cases of bacteremic gram-negative UTI (first and recurrent episodes) per 100,000 person-years, was calculated assuming that the entire population of Olmsted County was at risk of UTI. The 2000 Olmsted County census figures were used to compute the age- and gender-specific person-years denominator with a projected population growth rate after 2000 of 1.9% per year. Age was categorized into five groups (0–18, 19–39, 40–59, 60–79, and ≥ 80 years). The incidence rate was directly adjusted to the USA 2000 white population.6 All episodes of bacteremic gram-negative UTI were included as incident cases. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the incidence rate were estimated using a Poisson distribution. Similarly, the incidence rate was calculated for each pathogen.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates associated with a first episode of bacteremic gram-negative UTI. Patients were followed from the date of first episode of UTI until death or last healthcare encounter. Patients lost to follow-up were censored on the date of their last healthcare encounter.

Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify univariate risk factors for 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality. The following clinical variables were evaluated as potential risk factors: age in 10-year increments (as continuous variable), gender (male vs. female), site of acquisition (community-acquired vs. healthcare-associated or nosocomial), and causative organism (Escherichia coli vs. others). Since the number of nosocomial UTI was small, they were merged into a single category with healthcare-associated UTI. Similarly, UTI due to gram-negative bacilli other than E. coli were merged into a single category. To identify independent risk factors, variables were included in a multivariable Cox model if the p-value for a univariate association with mortality was ≤ 0.10.

In a post-hoc analysis, we compared the 28-day all-cause mortality rate of bacteremic UTI due to E. coli to that due to other gram-negative bacilli. We also compared the 28-day all-cause mortality rate of community-acquired bacteremic E. coli UTI to nosocomial and healthcare-associated bacteremic E. coli UTI using the log-rank test.

Logistic regression was used to test for a linear increase in resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and ceftazidime among gram-negative isolates throughout the study period. Only first episodes of bacteremic gram-negative UTI were included; recurrent episodes were excluded to avoid overestimating antimicrobial resistance rates. The 10-year study period was divided into five two-year intervals (1998–99, 2000–01, 2002–03, 2004–05 and 2006–07). Gram-negative isolates that were resistant or had intermediate susceptibility to a particular antimicrobial were classified as being resistant to that antimicrobial; otherwise, the isolate was classified as being susceptible.

JMP (version 8.0, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis. The level of significance for statistical testing was defined as p<0.05 (2-sided) unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

We identified 542 episodes of bacteremic gram-negative UTI during the study period (492 first episodes and 50 recurrent episodes). The median age of patients was 71 years (IQR: 52–82); and 353 (65.1%) were female. The median age was lower in females than in males (70 [IQR: 45–82] vs. 75 [IQR: 63–83] years, p=0.002). Most infections were community-acquired (57.4%); 35.6% were healthcare-associated, and 7.0% were nosocomial. Females were more likely to have community-acquired UTI than males (61.2% vs. 50.3%, p=0.02).

Incidence rate

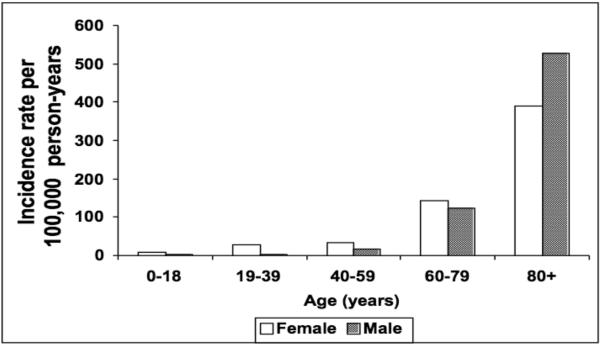

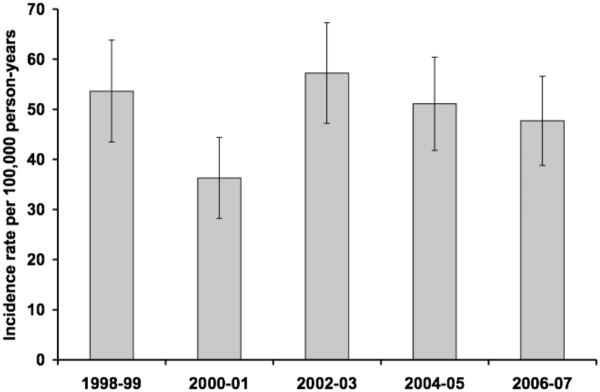

The overall age- and gender-adjusted incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI was 49.2 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI: 45.0–53.4), including recurrent episodes. The age-adjusted incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI per 100,000 person-years was 55.3 (95% CI: 49.5–61.2) in females and 44.6 (95% CI: 38.1–51.1) in males. The incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI increased with age in both females and males (Figure 1). There was no apparent change in the age- and gender-adjusted incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI throughout the 10-year study period (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection, by age and gender, 1998–2007.

Figure 2.

Age- and gender-adjusted incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection, by calendar year. NOTE. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Microbiology

Escherichia coli was the most common cause of bacteremic gram-negative UTI and accounted for 75% of episodes. The distribution of pathogens causing bacteremic gram-negative UTI is shown in Table 1. E. coli was the most common cause of bacteremic gram-negative UTI of all sites of infection acquisition, but it was more predominant among community-acquired UTI. E. coli contributed to 81% of community-acquired UTI, compared to 66% and 68% of healthcare-associated and nosocomial UTI, respectively.

Table 1.

Pathogen distribution of bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection, 1998–2007.

| Pathogen | Gender | Site of infection acquisition | Total N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | CA | HCA | Nosocomial | ||

| Escherichia coli | 291 | 115 | 252 | 128 | 26 | 406 (74.9) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 29 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 2 | 52 (9.6) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 14 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 1 | 25 (4.6) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 18 (3.3) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 (2.0) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 (1.1) |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 (0.9) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 (0.7) |

| Serratia marcescens | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 (0.6) |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 (0.6) |

| Morganella morganii | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.4) |

| Achromobacter spp. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 (0.9) |

CA: community-acquired, HCA: healthcare-associated.

Similarly, E. coli was the most common causative organism in all age groups, but it was more predominant in younger individuals. E. coli caused 85–89% of bacteremic gram-negative UTI in patients < 40 years old compared to 70–76% in patients ≥ 40 years old (Table 2). P. mirabilis was more common in older people; while P. mirabilis caused 4–7% of bacteremic gram-negative UTI in patients ≥ 40 years old, it did not contribute to bacteremic gram-negative UTI in patients < 40 years of age. P. aeruginosa was a more frequent pathogen in patients at the extremes of age and was identified in 6% of bacteremic gram-negative UTI in children and those ≥ 80 years old, but only 0–3% of cases in other age groups.

Table 2.

Pathogen distribution of bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection by age group, 1998–2007.

| Rank | Age group (years) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18 N=18 | 19–39 N=61 | 40–59 N=86 | 60–79 N=196 | ≥80 N=181 | ||||||

| 1 | E. coli | (89) | E. coli | (85) | E. coli | (74) | E. coli | (76) | E. coli | (70) |

| 2 | P. aeruginosa | (6) | K. pneumoniae | (10) | P. mirabilis | (7) | K. pneumoniae | (12) | K. pneumoniae | (9) |

| 3 | other | (6) | other | (5) | K. pneumoniae | (6) | P. mirabilis | (4) | P. mirabilis | (7) |

| 4 | K. oxytoca | (5) | P. aeruginosa | (3) | P. aeruginosa | (6) | ||||

| 5 | C. freundii | (2) | K. oxytoca | (2) | K. oxytoca | (2) | ||||

| 6 | P. aeruginosa | (1) | C. freundii | (1) | E. aerogenes | (2) | ||||

| 7 | other | (5) | other | (3) | other | (5) | ||||

Data are displayed as causative organism (percentage of the total in the cornsponding age group column).

The incidence rate of bacteremic E. coli UTI was higher in females than in males (age-adjusted incidence rate of 45.5 [95% CI: 40.2–50.8] vs. 26.2 [95% CI: 21.3–31.1] per 100,000 person-years) and the incidence rate of bacteremic K. oxytoca UTI was higher in males than in females (age-adjusted incidence rate of 2.2 [95% CI: 0.7–3.7] vs. 0.3 [95% CI: 0–0.7] per 100,000 person-years). There were no significant gender differences in bacteremic UTI caused by the other gram-negative bacilli (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted incidence rate of bacteremic urinary tract infection, by pathogen and gender. NOTE. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The six most common pathogens are included in the figure.

Mortality rate

The overall 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates following bacteremic gram-negative UTI were 4.9% (95% CI: 3.0–6.8) and 15.6% (95% CI: 12.4–18.8), respectively. The 28-day mortality rate increased by 66% for every 10-year increase in age, and similarly, the 1-year mortality rate increased by 80% for every 10-year increase in age (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). Even after adjustment for age, community-acquired UTI had lower 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates in comparison to healthcare-associated and nonsocomial UTI. Likewise, even after adjustment for age, E. coli UTI had lower 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates in comparison to all other organisms.

Table 3.

Factors associated with 28-day all-cause mortality in patients with bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection.

| Variable | Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.66 (1.24–2.36) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.12–2.10) | 0.004 |

| Male gender | 0.94 (0.38–2.14) | 0.89 | - | - |

| Site of acquisition: | ||||

| CA vs. HCA or nosocomial | 0.14 (0.04–0.37) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.06–0.54) | <0.001 |

| Causative organism: | ||||

| E. coli vs. other | 0.28 (0.12–0.62) | 0.002 | 0.39(0.17–0.88) | 0.02 |

| Year of diagnosis (per year) | 1.07 (0.93–1.25) | 0.31 | - | - |

HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval, CA: community-acquired, HCA: healthcare-associated.

Table 4.

Factors associated with 1-year all-cause mortality in patients with bacteremic gram-negative urinary tract infection.

| Variable | Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.80 (1.50–2.22) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.37–2.00) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.35 (0.85–2.14) | 0.20 | - | - |

| Site of acquisition: | ||||

| CA vs. HCA or nosocomial | 0.19 (0.11–0.32) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.14–0.44) | <0.001 |

| Causative organism: | ||||

| E. coli vs. other | 0.61 (0.39–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.17–0.88) | 0.04 |

| Year of diagnosis (per year) | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 0.30 | - | - |

HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval, CA: community-acquired, HCA: healthcare-associated.

The 28-day all-cause mortality rate in patients with bacteremic E. coli UTI was 3.0% compared to 10.7% in patients with bacteremic UTI due to other gram-negative bacilli (p<0.001). The 28-day all-cause mortality rate was also lower in patients with community-acquired compared to healthcare-associated or nosocomial bacteremic E. coli UTI (0.4% vs. 7.1%, p<0.001).

In vitro antimicrobial resistance rates

The overall antimicrobial resistance rates to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and ceftazidime among gram-negative isolates were 17.0%, 6.3%, 1.4%, respectively. There was a linear trend of increasing resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole from 10% to 24% (p=0.04) and ciprofloxacin from 1% to 8% (p=0.02) from 1998 to 2007 (Figure 4). Resistance rates to ceftazidime remained low throughout the study period with evidence of a possible linear trend towards decreasing resistance from 3% to 0% (p=0.07).

Figure 4.

In vitro antimicrobial resistance rates of gram-negative bloodstream isolates, by calendar year. NOTE. TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. P-value denotes a one-degree of freedom test for linear trend using logistic regression.

DISCUSSION

Incidence rate

The increase in incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI with age in our investigation was similar to that previously described in a population-based study of UTI in Calgary, Canada.1 The incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI remained relatively low in males < 60 years old, but substantially increased with age to exceed the incidence rate in females over the age of 80 years (Figure 1). This increase in the incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI in men over 60 years old is likely related to the increase in the incidence rate of benign prostatic hyperplasia in men.13–15

Microbiology

E. coli was the predominant pathogen of bacteremic gram-negative UTI, followed by K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis. This was consistent with results of a previous population-based study of UTI in North America.1 Although E. coli was the most common organism in both genders and in all age groups, it was more predominant in females and in individuals < 40 years old. In contrast, bacteremic K. oxytoca UTI was more common in males than in females and bacteremic P. mirabilis UTI was more common in individuals ≥ 40 years old. Bacteremic UTI caused by P. aeruginosa, on the other hand, was more common at the extremes of age.

Mortality rate

The 28-day all-cause mortality rate of 4.9% (95% CI: 3.0–6.8%) in patients with bacteremic gram-negative UTI in our population-based investigation was lower than that reported in studies from tertiary care centers where it ranged from 13 to 33%.3, 16–18 The lower mortality rate in our population-based study compared to that of hospital-based studies is consistent with our previous work of gram-negative bacteremia;10, 19 and is likely due to the lack of inclusion of referral patients who characteristically have more complications with worse outcomes.

The availability of long-term follow-up through the REP resources allowed an estimation of the 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients with bacteremic gram-negative UTI, which has not been reported previously. It is not surprising that more than 15% of patients did not survive beyond one year following bacteremic gram-negative UTI because the median age of patients was over 70 years. Without adjustment for acute severity of illness or appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy, older age was associated with higher 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates. E. coli and community-acquired infection acquisition were both independently associated with lower mortality rates even after adjustment for age.

In vitro antimicrobial resistance rates

The increase in antimicrobial resistance rates among gram-negative isolates to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin over the past decade in our investigation was consistent with results of recent studies of E. coli bloodstream and urinary isolates.20–24 E. coli accounted for nearly 75% of gram-negative isolates in our survey. Fortunately, resistance rates to third-generation cephalosporins remained low and stable in our study, contrary to the results of some recent reports.21, 22

Up to 8% of gram-negative organisms that caused bacteremic UTI were resistant to fluoroquinolones during the years 2006–07. This increase in antimicrobial resistance rates prompts concern for initial selection of empiric antimicrobial therapy since inappropriate initial empiric therapy in bacteremic patients has been associated with worse outcomes.25 Based on the current antimicrobial resistance rates in our geographic area, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, for example, are favored, rather than fluoroquinolones, for the empiric therapy of upper UTI in moderately and severely ill patients who require admission to the hospital. In addition, because fluoroquinolones are safe and effective in the treatment of bacteremic UTI and have the highest bioavailability among all available oral antimicrobials with gram-negative activity,26,27 the trend of increasing resistance to fluoroquinolones will likely restrict availability of a reliable oral therapy as “switch” therapy for bacteremic UTI. If this trend of increasing resistance to fluoroquinolones continues, it may result in a sizable increase in the cost of healthcare if parenteral therapy has to be extended due to lack of effective oral options.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of our study is the population-based design and, therefore, lack of referral bias. The availability of prolonged follow-up through the REP resources is another unique advantage of our work.

Our study has limitations. First, our data was derived from one geographic area. Studies from multiple geographic locations may provide a more comprehensive view. Second, we might have underestimated the incidence rate of bacteremic UTI, as blood cultures were not routinely obtained in all patients with UTI. In addition, some patients with UTI might have received empiric antimicrobial therapy prior to the collection of blood cultures, which might have lowered the sensitivity of blood cultures. Although we did not collect data to examine this hypothesis, it is possible that if a decision to obtain blood cultures was influenced by age or gender, this could have affected some aspects of our age- and gender-based conclusions. In addition, we did not evaluate the appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy in the survival model. Although the study demonstrated trends of increasing resistance to certain antimicrobial agents, the study could not contribute an increasing mortality to the respective antimicrobial therapy. Finally, the population of Olmsted County consisted primarily of middle class whites; therefore, our study results may be generalized only to communities with similar population characteristics.

In summary, this is the first population-based study that defined the incidence rate, microbiology, outcome, and in vitro antimicrobial resistance trends of bacteremic gram-negative UTI. The incidence rate of bacteremic gram-negative UTI increased with age and was higher in females than in males, especially those < 60 years of age. Most cases of bacteremic gram-negative UTI were community-acquired and E. coli was the predominant pathogen. Both community-acquired and E. coli UTIs were associated with lower 28-day and 1-year all-cause mortality rates. In contrast, increasing age was associated with higher mortality rates. The mortality rate in our population-based study was lower than previously reported mortality rates from tertiary care centers. Finally, we demonstrated linear trends of increasing resistance among gram-negative isolates to sulfonamides and fluoroquinolones over the past decade. However, resistance rates to third-generation cephalosporins remained low with a linear trend towards decreasing resistance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emily Vetter and Mary Ann Butler for providing us with vital data from the microbiology laboratory databases at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester and Olmsted Medical Center.

The authors thank Susan Schrage, Susan Stotz, R.N., and all the staff at the Rochester Epidemiology Project for their administrative help and support.

Funding. The study received funding from the Small Grants Program and the Baddour Family Fund at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. The funding source had no role in study design. This work was made possible by research grant R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. MNA, JEE, and LMB: No conflict.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Laupland KB, Ross T, Pitout JD, Church DL, Gregson DB. Community-onset urinary tract infections: a population-based assessment. Infection. 2007;35:150–3. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honkinen O, Jahnukainen T, Mertsola J, Eskola J, Ruuskanen O. Bacteremic urinary tract infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:630–4. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackermann RJ, Monroe PW. Bacteremic urinary tract infection in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:927–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan JG, Bordley DR, Polito R. Initial management of serious urinary tract infection: epidemiologic guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:190–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02599521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahagon Y, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Prevalence and predictive features of bacteremic urinary tract infection in emergency department patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:349–52. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Census Bureau Olmsted County QuickFacts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/27/27109.html. Accessed December 22, 2007.

- 7.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steckelberg JM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Ilstrup DM, Rouse MS, Wilson WR. Influence of referral bias on the apparent clinical spectrum of infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 1990;88:582–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90521-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tleyjeh IM, Steckelberg JM, Murad HS, Anavekar NS, Ghomrawi HM, Mirzoyev Z, et al. Temporal trends in infective endocarditis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. JAMA. 2005;293:3022–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Hasan MN, Wilson JW, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: a population-based study. Am J Med. 2008;121:702–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uslan DZ, Crane SJ, Steckelberg JM, Cockerill FR, 3rd, St Sauver JL, Wilson WR, et al. Age- and sex-associated trends in bloodstream infection: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:834–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, et al. Health care-associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:791–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarma AV, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Roberts RO, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. A population based study of incidence and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1987 to 1997. J Urol. 2005;173:2048–53. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158443.13918.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick JM. The natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2006;97(Suppl 2):3–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06097.x. discussion 21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Roberts RO, Guess HA, Lieber MM. Longitudinal prostate growth rates during 5 years in randomly selected community men 40 to 79 years old. J Urol. 1999;161:1174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryan CS, Reynolds KL. Community-acquired bacteremic urinary tract infection: epidemiology and outcome. J Urol. 1984;132:490–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryan CS, Reynolds KL. Hospital-acquired bacteremic urinary tract infection: epidemiology and outcome. J Urol. 1984;132:494–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tal S, Guller V, Levi S, Bardenstein R, Berger D, Gurevich I, et al. Profile and prognosis of febrile elderly patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J Infect. 2005;50:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Epidemiology and outcome of Klebsiella species bloodstream infection: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0410. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Antimicrobial resistance trends of Escherichia coli bloodstream isolates: a population-based study, 1998–2007. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:169–74. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laupland KB, Gregson DB, Church DL, Ross T, Pitout JD. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in a large Canadian region. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:1041–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peralta G, Sanchez MB, Garrido JC, De Benito I, Cano ME, Martinez-Martinez L, et al. Impact of antibiotic resistance and of adequate empirical antibiotic treatment in the prognosis of patients with Escherichia coli bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:855–63. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Hasan MN, Razonable RR, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Incidence rate and outcome of Gram-negative bloodstream infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:835–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau SM, Peng MY, Chang FY. Resistance rates to commonly used antimicrobials among pathogens of both bacteremic and non-bacteremic community-acquired urinary tract infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:185–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, Kim HB, Kim EC, et al. Bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli: risk factors for mortality and impact of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy on outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:760–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.760-766.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouza E, Diaz-Lopez MD, Bernaldo de Quiros JC, Rodriguez-Creixems M. Ciprofloxacin in patients with bacteremic infections. The Spanish Group for the Study of Ciprofloxacin. Am J Med. 1989;87:228S–231S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mombelli G, Pezzoli R, Pinoja-Lutz G, Monotti R, Marone C, Franciolli M. Oral vs intravenous ciprofloxacin in the initial empirical management of severe pyelonephritis or complicated urinary tract infections: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:53–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]