Abstract

Objective

To examine α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) binding and β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide load in superior frontal cortex (SFC) across clinical and neuropathological stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Design

Quantitative measures of α7 nAChR by [3H]methyllycaconitine binding and Aβ concentration by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in SFC were compared across subjects with antemortem clinical classification of no cognitive impairment (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or mild-moderate AD (mAD), and with post-mortem neuropathological diagnoses.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Subjects

Twenty-nine elderly retired clergy.

Results

Higher concentrations of total Aβ peptide in SFC were associated with clinical diagnosis of mAD (p=0.015), lower Mini Mental State Examination scores (p=0.0033), presence of cortical Aβ plaques (p=0.015), and likelihood of AD diagnosis by the NIA-Reagan criteria (p=0.0015). Increased α7 nAChR binding was associated with NIA-Reagan diagnosis (p=0.021) and, albeit weakly, the presence of cortical Aβ plaques (p=0.079). There was no correlation between the two biochemical measures.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that during the clinical progression from normal cognition to neurodegenerative disease state, total Aβ peptide concentration increases, while α7 nAChRs remain relatively stable in SFC. Regardless of subjects’ clinical status, however, elevated α7 nAChR binding is associated with increased Aβ plaque pathology, supporting the hypothesis that cellular expression of these receptors may be up-regulated selectively in Aβ plaque-burdened brain areas.

Keywords: acetylcholine, mild cognitive impairment, cholinergic, nicotinic, receptors, amyloid, dementia, frontal cortex

Introduction

Cholinergic synaptic dysfunction contributes to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). These changes may be due, in part, to increased concentrations of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides1 and their interactions with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are essential for normal cognitive function2, 3. Aβ binds to nAChRs, particularly the α7 subclass4, 5; this may alter receptor function6–10 and also result in Aβ internalization, fibrillization, and deposition into plaques and cerebral vasculature4, 11–13. The status of α7 nAChRs in AD is controversial as there are reports of increases, decreases, or stability in AD14–18. While non-α7 nAChR binding in frontal cortex declines early in AD19, quantitative biochemical studies specific for α7 nAChRs in subjects with preclinical and early AD remain to be performed. The current study quantified α7 nAChR binding and total Aβ peptide concentration in the superior frontal cortex (SFC) from subjects who participated in the Religious Orders Study20, 21. The status of these two biochemical measures was examined across subjects’ groups defined by clinical diagnoses of no cognitive impairment (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and early AD stage (mild-moderate AD, mAD), or neuropathological diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study included 29 participants in the Religious Orders Study, a longitudinal clinical-pathological study of aging and AD in retired Catholic nuns, priests, and brothers20. Inclusion criteria and a description of the clinical evaluation have been published20, 21. At the last clinical evaluation (<12 months prior to death), subjects were classified as NCI, MCI, or mild-moderate AD (see Table 1). Diagnosis of AD dementia was made using standard criteria22. MCI was defined as impairment on neuropsychological testing, but without a diagnosis of dementia by the examining neurologist23, criteria similar to those describing patients who were not cognitively intact, but nonetheless did not meet the criteria for dementia24–27. A consensus conference of neurologists and neuropsychologists reviewed all the clinical and neuroimaging data, medical records and interviews with family members, and assigned a final diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and neuropathological characteristics by diagnostic groups

| Clinical Diagnosis |

CERAD Diagnosis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | NCI (N=12) | MCI (N=9) | mAD (N=8) | P value | Not AD (N=10) | AD§ (N=19) | P value | |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 86.1 (5.5) | 85.3 (3.6) | 89.4 (5.0) | 0.1 a | 85.0 (4.5) | 87.7 (5.0) | 0.2 a | |

| Male, N (%) | 4 (33) | 3 (33) | 3 (38) | 1.0 b | 4 (40) | 6 (32) | 0.7 b | |

| Education, mean (SD), yr | 18.5 (2.7) | 18.9 (2.5) | 15.9 (3.3) | 0.1 a | 17.8 (3.0) | 17.9 (3.1) | 0.9 a | |

| APOE ε4, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 0.074 b | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 1.0 b | |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 28.7 (1.1)* | 27.1 (2.5) | 12.8 (5.8) | < 0.0001 a | 27.7 (2.5) | 21.4 (8.8)* | 0.055 a | |

| PMI, mean (SD), hr | 5.3 (3.3) | 5.0 (3.6) | 4.4 (2.1) | 0.8a | 5.8 (3.9) | 4.5 (2.5) | 0.6 a | |

| Braak Stage, N | I – II | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.036 a | 4 | 1 | 0.0040 a |

| III – IV | 10 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 12 | |||

| V | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |||

| NIA Reagan Dx, N | LL | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0.018 a | 10 | 0 | < 0.0001 a |

| IL | 7 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 16 | |||

| HL | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |||

| CERAD Dx, N | Not AD | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0.040 b | -- | -- | |

| AD§ | 7 | 4 | 8 | -- | -- | |||

Includes CERAD diagnosis of possible, probable, and definite AD

MMSE not available for 1 case

Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test

Fisher’s exact test

Neuropathological evaluation

Neuropathological diagnosis of AD (possible, probable, or definite AD) or Not AD (Table 1) was based on modified criteria by the Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD)28 which applied semi-quantitative estimates of neuritic plaque density by a board-certified neuropathologist blinded to the clinical diagnosis29. Subjects were also assigned an NIA Reagan neuropathological diagnosis30 and a Braak score based on the presence of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)31. Subjects with pathology other than AD were excluded from the study.

[3H]MLA binding assay

Fresh frozen SFC (Brodmann area 9) gray matter was divided into aliquots for nAChR binding and Aβ peptide enzyme linked immunoadsorbent assay (ELISA). For α7 nAChR binding, samples were homogenized in 10 volumes of 50 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH=7.0), centrifuged twice at 40,000 × g for 10 minutes, re-suspended in Tris buffer and stored at −80°C. Samples were thawed and re-suspended in an equal volume of Tris buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)32, 33. Samples, 0.5 mg protein each, were combined with 9.5 nM [3H]MLA (43 Ci/mmol, Tocris Cookson Ltd., Bristol, UK) in Tris HCl buffer containing 0.1% BSA. Non-specific binding was measured in the presence of 1 mM nicotine. After a 2 hr incubation on ice, bound ligand was separated from free ligand using Whatman GF/B filters, presoaked in 0.3% polyethyleneimine. Filters were rinsed with Tris HCl buffer, placed in scintillation vials, and shaken in scintillation fluid for 1 hour before radioactivity was determined. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and non-specific binding. Results were expressed as femtomoles/mg protein.

Aβ ELISA Assay

The Aβ assay was performed using a previously reported protocol34. Frozen SFC samples were homogenized (150mg tissue wet weight/ml PBS buffer, pH = 7.4) and 30 mg of homogenized tissue were sonicated in 70% formic acid (FA), and centrifuged at 109,000 × g at 4°C for 1 hour, resulting in samples containing both soluble and FA-extracted insoluble Aβ peptides. The supernatant was neutralized with 1M Tris and 0.5M sodium phosphate, and the samples assayed using a fluorescent-based ELISA (BioSource, Carlsbad, CA) following the kit’s instructions, with a capture antibody specific for the NH2-terminus of Aβ(amino acids 1–16), and detection antibodies specific for Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides. Values were determined from standard curves using synthetic Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 peptides (BioSource) and expressed as pmoles/gram wet brain tissue. “Total” Aβvalues represent a sum of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 peptide values.

Statistical analysis

Aβ levels were log-transformed due to data skewness. Comparisons of demographic characteristics, MLA binding and Aβ levels between clinically- or neuropathologically-defined groups were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal Wallis test, or the Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The association between demographic characteristics and MLA binding or Aβ levels was assessed by Spearman rank correlation or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Partial correlation was used for additional analyses adjusting for age. The correlation between MLA binding and Aβ levels was assessed by Spearman correlation. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Clinical and Pathological Analyses

The three clinical groups differed in MMSE scores (p<0.0001), with the mAD group performing worse than both the NCI and MCI groups (Table 1). Clinical diagnostic groups also differed in CERAD diagnosis (p=0.040), Braak staging (p=0.036), and the NIA-Reagan diagnosis (p=0.018), with the mAD subjects being more advanced neuropathologically compared to both the MCI and NCI groups (Table 1).

Subjects with a CERAD diagnosis of AD (CERAD < 4, possible, probable or definite AD; positive for cortical plaques) had lower MMSE scores (p=0.055), and more advanced Braak stages and NIA-Reagan neuropathologic diagnoses (p=0.004 and p < 0.0001; Table 1) than the Not AD group (CERAD = 4; no cortical plaques).

MLA binding and Aβ concentrations across clinical and neuropathologic categories

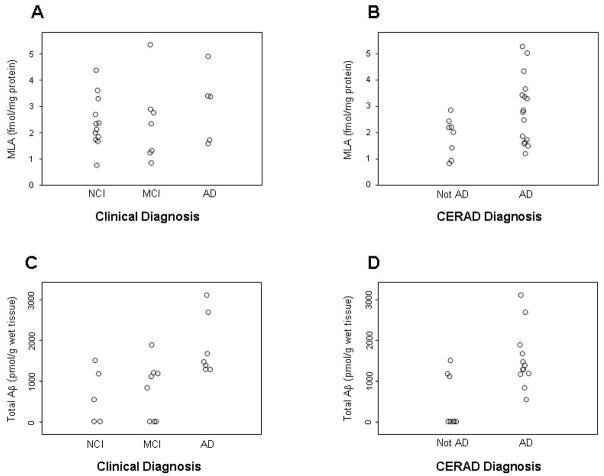

MLA binding levels were slightly higher in mAD subjects, however, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2). Clinical groups differed in total Aβ (combined Aβ42 and Aβ40; p=0.015; Figure 1) and Aβ42 (p=0.022), but not Aβ40, concentrations, with mAD subjects having the highest levels.

Table 2.

Superior frontal cortex MLA binding and Aβ ELISA levels by diagnostic groups

| Clinical Diagnosis |

CERAD Diagnosis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | NCI | MCI | mAD | P value a | Not AD | AD§ | P value a |

| MLA, mean (SD) | 2.4 ± 1.0 (N=12) | 2.4 ± 1.5 (N=7) | 3.0 ± 1.4 (N=5) | 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 (N=8) | 2.9 ±1.3 (N=16) | 0.079 |

| Aβ40*, mean (SD) | 2.3 ± 1.6 (N=5) | 2.5 ± 2.2 (N=8) | 4.3 ± 1.7 (N=7) | 0.1 | 1.7 ± 1.9 (N=8) | 4.0 ±1.6 (N=12) | 0.063 |

| Aβ42*, mean (SD) | 5.0 ± 2.5 (N=5) | 5.2 ±2.4 (N=8) | 7.3 ± 0.3 (N=7) | 0.022 | 4.1 ± 2.5 (N=8) | 7.1 ±0.4 (N=12) | 0.021 |

| Total Aβ*, mean (SD) | 5.1 ± 2.5 (N=5) | 5.3 ±2.4 (N=8) | 7.5 ± 0.4 (N=7) | 0.015 | 4.2 ± 2.4 (N=8) | 7.3 ±0.5 (N=12) | 0.015 |

Includes CERAD diagnosis of possible, probable, and definite AD

Aβ levels were log-transformed

Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test

Figure 1.

α7 binding (A,B) and total Aβ peptide concentrations (C,D) in the frontal cortex from subjects categorized into clinical diagnostic groups of NCI, MCI and AD (A,C), or into neuropathological groups of Not AD and AD (possible, probable, definite) by modified CERAD criteria (B,D).

Subjects with a CERAD diagnosis of AD had higher MLA binding (p = 0.079; Figure 1), and higher concentrations of Aβ42 (p = 0.021), Aβ40 (p = 0.063), and total Aβ (p = 0.015; Table 2; Figure 1) in the SFC when compared to those with CERAD diagnosis of Not AD.

MLA binding and Aβ concentration: association with clinical-neuropathological factors

There was no association of MLA binding with any of the demographic or clinical variables examined. Higher MLA binding levels correlated with greater likelihood of AD by the NIA-Reagan diagnosis (r=-0.47, p=0.021; Table 3), and weakly with Braak staging. There was an association of higher Aβ concentrations with more advanced age (r=0.48–0.56, p=0.011–0.032; Table 3), but not with sex, education, the presence of APOEε4 allele, or post-mortem interval. Higher concentrations of total Aβ and Aβ42, but not Aβ40, correlated with lower MMSE scores (r=−0.62 for both, p=0.0033 and 0.0038; Table 3). In addition, higher total Aβ and Aβ42 concentrations correlated with worse neuropathological scores (r=0.62–0.70, p<0.01), as did Aβ40 concentrations, although to a lesser extent (Table 3). Adjusting for age, partial correlation showed similar results, although it yielded smaller correlation coefficients. There was no correlation between MLA binding and Aβ protein concentrations.

Table 3.

Association between clinical/neuropathological variables and superior frontal cortex MLA binding and Aβ ELISA levels

| Variable | MLA (N=24) | Aβ40 (N=20) | Aβ42 (N=20) | Total Aβ (N=20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -- | r = 0.48, p = 0.032 | r = 0.56, p = 0.011 | r = 0.55, p = 0.012 |

| Sex | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Education | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| APOE ε4 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| MMSE | (r = −0.25, p = 0.26) | (r = −0.36, p = 0.12) | r = −0.62, p = 0.0038 | r = −0.62, p = 0.0033 |

| PMI | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Braak stage | (r = 0.40, p = 0.053) | (r = 0.36, p = 0.12) | r = 0.70, p = 0.0005 | r = 0.62, p = 0.0035 |

| NIA Reagan Dx | r = −0.47, p = 0.021 | r = −0.52, p = 0.020 | r = −0.63, p = 0.0031 | r = −0.66, p = 0.0015 |

r: Spearman rank correlation coefficient

--: Not statistically significant

Comment

This study examined SFC α7 nAChR binding and Aβ peptide concentrations across the clinical and neuropathologic categories of AD. Both markers were assayed in the same samples of cortical tissue from subjects who were clinically characterized within 12 months before death, and neuropathologically evaluated postmortem. We did not detect significant changes in SFC α7 nAChR binding across clinical diagnostic groups. However, a trend toward elevated α7 nAChR binding levels was evident in subjects with CERAD diagnoses of AD (possible, probable or definite) relative to Not AD subjects (without neuritic Aβ plaques). Total (sum of Aβ42 and Aβ40) and Aβ42 concentrations were elevated in the CERAD-AD group compared to the CERAD-Not AD group, as well as in the clinical mAD compared to the MCI and NCI groups. The increase in α7 nAChRs in Aβ plaque-positive subjects, despite the lack of an association with Aβ concentrations, indicates that cellular expression of this receptor is influenced, either directly or indirectly, by the presence of senile plaques. This is in agreement with previous studies in AD patients and animal models35, 36, and is supported further by the current observation that the correlation between α7 nAChR levels and neuropathological staging was stronger using NIA-Reagan criteria compared to Braak staging, the latter relying only on NFTs for stage designation31.

The apparent stability of α7 nAChRs across clinical categories of NCI, MCI and mAD, and the lack of an association with MMSE scores, could be explained by the presence of plaques in all clinical groups. Cortical plaques were present in more than half of our NCI cases (Table 1), in agreement with previous reports of a substantial AD pathology in cognitively normal aged individuals29, 37–41. Although these studies would benefit from examining larger numbers of cognitively intact subjects free of any Aβ pathology, such individuals are rare, as Aβ plaques are a common feature in brains of elderly individuals37, 38, 40, 41. Furthermore, the pathological burden of Aβ includes not only insoluble fibrils in plaques, but also soluble Aβoligomers42. The impact of these distinct pools of Aβ upon α7 nAChR binding in preclinical, early/moderate and severe end-stage AD cases will be an important question to answer in future studies.

There are several possible explanations for the observed association between Aβ plaques and increased α7 nAChR binding. Plaques may serve as reservoirs of soluble Aβ species1, which can bind with high affinity to neuronal α7 receptors4,5 into a complex that is subsequently internalized12. This may result in a compensatory increase in expression of α7 nAChR on the cell surface. Additionally, excessive intracellular accumulation of Aβ42 and subsequent neuronal lysis may contribute to plaque pathology12, potentially creating a cycle of neuronal degeneration and Aβ plaque deposition in AD. High concentrations of fibrillar Aβ in plaques, or soluble Aβ in the vicinity of these structures, may also influence the up-regulation of α7 nAChR by reactive astrocytes. Astrocytes proliferate and display increased α7 nAChR density in the presence of Aβ plaques36, 43, 44, and up-regulate nAChR mRNA expression and protein levels when exposed to Aβ in vitro45. Receptor binding assays cannot differentiate the relative contribution of different cell types to the overall regional expression of α7 nAChRs detected in tissue homogenates. Adding to this complexity are the post- and pre-synaptic sites of expression of α7 nAChRs, involving both local neuronal circuitry and afferent projections from distant neuronal cell populations. In this regard, a recent single-cell expression profiling study demonstrated up-regulation of α7 nAChR mRNA in cortical-projecting basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in mAD subjects46, suggesting that changes in cortical α7 protein levels involve presynaptic elements on an important cholinergic afferent system. Collectively, these studies suggest that in the SFC, α7 nAChRs levels reported here reflect changes both in cortical-projecting cholinergic basal forebrain neurons and regional cell-specific expression of these receptors in response to Aβ pathology.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrate that cognitive decline in mAD is not associated with detectable changes in cortical α7 nAChR binding levels. In contrast, Aβ concentrations increased in mAD and correlated with cognitive impairment, in accord with reported associations of increased Aβ load with cognitive decline in AD47, 48. The observed trend for increased SFC α7 in subjects with plaques is in agreement with a previously reported positive correlation between α-bungarotoxin binding and Aβ plaque density35, and warrants further investigation. These changes are in contrast with reports of reduced cortical α4 nAChR immunoreactivity with increased Aβ plaque densities, and a loss of epibatidine binding with increased Aβ42 concentrations35. Thus, α7 and non-α7 nAChRs may be differentially affected by Aβ pathology. In vivo PET imaging techniques using radiolabeled probes for early detection of Aβ plaques49, 50 and changes in select nAChRs51 may act as early biomarkers for AD and will enable the timely implementation of appropriate therapies.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: NIA Grants AG14449 and AG10610.

We thank Theresa Landers-Concatelli and William R. Paljug for expert technical assistance. We are indebted to the support of the participants in the Religious Orders Study; for a list of participating groups see the website http://www.rush.edu/rumc/page-R12394.html.

References

- 1.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newhouse PA, Potter P, Corwin J, Lenox R. Acute nicotinic blockade produces cognitive impairment in normal humans. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:480–484. doi: 10.1007/BF02247425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadir A, Almkvist O, Wall A, et al. PET imaging of cortical 11C-nicotine binding correlates with the cognitive function of attention in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H-Y, Lee DHS, D’Andrea MR, et al. beta-amyloid(1–42) binds to alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity. Implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5626–5632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H-Y, Lee DHS, Davis CB, Shank P. Amyloid peptide (1-42) binds selectively and with picomolar affinity to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1155–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettit DL, Shao Z, Yakel JL. Beta-Amyloid(1–42) peptide directly modulates nicotinic receptors in the rat hippocampal slice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Q-S, Kawai H, Berg DK. Beta-Amyloid peptide blocks the response of alpha7-containing nicotinic receptors on hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4734–4739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081553598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dineley KT, Westerman M, Bui D, et al. Beta-amyloid activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade via hippocampal alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: In vitro and in vivo mechanisms related to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4125–4133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dineley KT, Bell K, Bui D, Sweatt JD. Beta -Amyloid peptide activates alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25056–25061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougherty JJ, Wu J, Nichols RA. Beta-amyloid regulation of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in rat hippocampus and neocortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6740–6747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06740.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Andrea MR, Nagele RG, Wang HY, et al. Evidence that neurones accumulating amyloid can undergo lysis to form amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Histopathaology. 2001;38:120–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagele RG, D’Andrea MR, Anderson WJ, Wang HY. Intracellular accumulation of beta-amyloid(1–42) in neurons is facilitated by the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;110:199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifford PM, Siu G, Kosciuk M, et al. alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression by vascular smooth muscle cells facilitates the deposition of Abeta peptides and promotes cerebrovascular amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.092. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Ruiz CM, Court JA, Molnar E, et al. Alpha4 but not alpha3 and alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits are lost from the temporal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1635–1640. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson K, Nordberg A. Neuronal nicotinic receptors in the human brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:75–111. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Court JA, Martin-Ruiz CM, Piggott M, et al. Nicotinic receptor abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psych. 2001;49:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordberg A. Nicotinic receptor abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Biol Psych. 2001;49:200–210. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry EK, Martin-Ruiz CM, Court JA. Nicotinic receptor subtypes in human brain related to aging and dementia. Alcohol. 2001;24:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabbagh MN, Shah F, Reid RT, et al. Pathologic and nicotinic receptor binding differences between mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer disease, and aging. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1771–1776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mufson EJ, Counts SE, Che S, Ginsberg SD. Neuronal gene expression profiling: uncovering the molecular biology of neurodegenerative disease. Prog Brain Res. 2006;158:197–222. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)58010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert M, Smith LA, Steer PA, et al. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devanand DP, Folz M, Gorlyn M, et al. Questionable dementia: clinical course and predictors of outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC. Mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris JC, Price AL. Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:101–118. doi: 10.1385/jmn:17:2:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology. 2005;64:834–841. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152982.47274.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute working group on diagnosis criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of AD. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies AR, Hardick DJ, Blagbrough IS, et al. Characterization of the binding of [3H]methyllycaconitine: a new radioligand for labelling alpha 7-type neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:679–690. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward JM, Cockcroft VB, Lunt GG, et al. Methyllycaconitine: a selective probe for neuronal alpha-bungarotoxin binding sites. FEBS Lett. 1990;270:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81231-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, et al. Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:1630–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry E, Martin-Ruiz C, Lee M, et al. Nicotinic receptor subtypes in human brain ageing, Alzheimer and Lewy body diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;393:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu WF, Guan ZZ, Bogdanovic N, Nordberg A. High selective expression of alpha7 nicotinic receptors on astrocytes in the brains of patients with sporadic Alzheimer and patients carrying Swedish APP 670/671 mutation: a possible association with neuritic plaques. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mufson EJ, Chen EY, Cochran EJ, et al. Entorhinal cortex beta-amyloid load in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:469–490. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forman MS, Mufson EJ, Leurgans S, et al. Cortical biochemistry in MCI and Alzheimer disease: lack of correlation with clinical diagnosis. Neurology. 2007;68:757–763. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256373.39415.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66:1837–1844. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markesbery WR, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, et al. Neuropathologic substrate of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, et al. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:665–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain As distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:328–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teaktong T, Graham A, Court J, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a selective increase in alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor immunoreactivity in astrocytes. Glia. 2003;41:207–211. doi: 10.1002/glia.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teaktong T, Graham AJ, Court JA, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor immunohistochemisry in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: differential neuronal and astroglial pathology. J Neurol Sci. 2004;225:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiu J, Nordberg A, Zhang JT, Guan ZZ. Expression of nicotinic receptors on primary cultures of rat astrocytes and up-regulation of the alpha7, alpha4 and beta2 subunits in response to nanomolar concentration of the beta-amyloid peptide(1–42) Neurochem Int. 2005;47:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Counts SE, He B, Che S, et al. alpha7 nicotinic receptor up-regulation in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in early stage Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1771–1776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings BJ, Pike CJ, Shankle R, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid deposition and other measures of neuropathology predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naslund J, Haroutunian V, Mohs R, et al. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid s-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. JAMA. 2000;283:1571–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Ikonomovic MD, et al. Binding of the positron emission tomography tracer Pittsburgh compound-B reflects the amount of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease brain but not in transgenic mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10598–10606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2990-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nordberg A. Amyloid imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1636–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nordberg A. Visualization of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors in brain by positron emission tomography. In: Ezio G, Pepeu G, editors. The brain cholinergic system. London: Martin Dunitz; 2006. [Google Scholar]