Abstract

Objective:

Youth exposure to intimate partner violence has been theorized to increase the risk of adverse outcomes in adulthood including substance-use problems. However, the limited research on the association between early exposure to intimate partner violence and later alcohol- or drug-use problems is inconclusive. Using a prospective design, this study investigates whether adolescent exposure to intimate partner violence increases the risk for problem substance use in early adulthood and whether this relationship differs by gender.

Method:

The study uses a subsample (n = 508) of participants from the Rochester Youth Development Study, a longitudinal study of urban, largely minority adolescents that oversampled youth at high risk for antisocial behavior and drug use. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess whether adolescent exposure to intimate partner violence predicted increased odds of four indicators of problem substance use in early adulthood, controlling for parental substance use, adolescent maltreatment, and sociodemographic risk factors.

Results:

Exposure to severe intimate partner violence as an adolescent significantly increased the odds of alcohol-use problems in early adulthood for young women (odds ratio = 5.63, p < .05) but not for young men. Exposure to intimate partner violence did not increase the odds of other substance-use indicators for either gender.

Conclusions:

Girls exposed to intimate partner violence may be at increased risk for problems with alcohol use in adulthood and should be a target for prevention and intervention efforts. Overall, however, the association between exposure to intimate partner violence and later substance-use problems is less than anticipated in this high-risk community sample.

Substance use has been and remains a significant public health target associated with multiple disruptions in family life and substantial personal and societal costs, including heightened risk for intimate partner violence (IPV; Klostermann and Fals-Stewart, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Violence in the family is also a national public health concern in view of its frequency (Straus and Gelles, 1990), its immediate health and safety concerns for victims, and its short- and long-term effects across a range of developmental domains (Graham-Bermann and Edleson, 2001; McCloskey et al., 1995; Reno, 1999; Saunders, 2003).

Research into the consequences of family violence has historically been grouped into two fairly distinct sets of literatures. One line of inquiry examines the consequences of directly experienced childhood or adolescent maltreatment. Recent prospective research establishes that maltreatment is a relatively robust predictor of delinquency, crime, conduct problems (Ireland et al., 2002; Smith and Thornberry, 1995; Widom, 1998), and possibly long-term drug and alcohol use among women (Widom et al., 2006, 2007). The second line of research considers the consequences of experiencing family violence vicariously by either witnessing IPV or living in a home rife with serious conflict (Jouriles et al., 2001). However, the developmental consequences of growing up in a partner-violent family are less understood than the consequences of maltreatment (Carlson, 2000; Jouriles et al., 1998; Rossman, 2001; Wolfe et al., 2003). In fact, very few longitudinal studies of links between exposure to parental IPV and substance use among young adults exist, although family violence and addiction are often thought to be “intertwined over the life course” (Wekerle and Wall, 2002, p. 3). Furthermore, because each line of research explores a narrow category of family violence, the specific impact of one type of family violence net of other types of family violence remains an open question (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Hartley, 2002; Rossman and Rosenberg, 1999; Saunders, 2003).

Although the intertwined relationship between family violence and substance use can be illuminated in a variety of ways, the facet explored here focuses on adolescent exposure to parental (or guardian) IPV and subsequent substance-use patterns in young adulthood. To estimate the relationship, we use longitudinal data on parental and youth participants from a large community sample with multiple reporters; diverse measurement approaches; limited sample attrition; long-term follow-up; and controls for confounding factors, including other forms of family violence and parental substance use.

Extent of intimate-partner-violence exposure and substance use

Assessing the prevalence of child exposure to parental partner violence is complicated because there is little uniformity in definitions of IPV (Levendosky et al., 2007). In addition, whether a child living in the home actually witnesses IPV remains largely unknown (Holden, 2003). As a result, the estimate of the number of children exposed to IPV remains very incomplete (Osofsky, 2003). Generally, community surveys find that about one in six couples experience IPV annually (Jouriles et al., 2001; Schafer et al., 1998; Straus and Gelles, 1990; Wolak and Finkelhor, 1998). Rates are higher among younger couples, cohabiting couples, and couples with children (Bardone et al., 1996; Magdol et al., 1998). McDonald et al. (2006) estimated that “approximately 15.5 million American children live in dual-parent house-holds in which partner-violence has occurred in the past year” (p. 139). Others have estimated that between 10% and 20% of children, or up to 10 million children annually, are exposed to IPV (Carlson, 2000; Jaffe et al., 1990; Straus, 1992), and Fantuzzo and Fusco (2007) estimated that about four of five children living in a partner-violent home witness or hear partner violence (see also Ernst et al., 2006).

In contrast, a number of national studies monitor substance use and abuse during adolescence and young adulthood. For example, using Monitoring the Future, Johnston et al. (2007) estimated that in 2006, 73% of 12th graders used alcohol, and 56% reported “being drunk,” and these prevalence rates increased in young adulthood to 89% and 81%, respectively. Use of illegal substances, from marijuana to heroin and crack, is also quite common, with 50% of 12th graders and graduating seniors using some illegal drug, most commonly marijuana. In young adulthood, the proportion rises to about 60%, with drug use other than marijuana at 35%. About 10% of adults go on to develop a drug-use disorder during their lives (Compton et al., 2007).

General conceptual model: Developmental consequences of intimate partner violence

A comprehensive review of existing theories of family violence and the role of the family in the etiology of substance abuse is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we focus on the life-course interactional theory that underpins work on the Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS) and has been successfully applied to the study of evolving behavior trajectories such as antisocial behavior and drug use (Bushway et al., 2003; Ireland et al., 2002; Thornberry et al., 2003; Thornberry and Krohn, 2001). Interactional theory argues that stressors such as family dysfunction and violence can set in motion high-risk behaviors that tend to perpetuate themselves because they foreclose the opportunity for prosocial experiences—with conventional peers, with positive adults, and with institutions such as schools—and interrupt the development of social competencies that can offset developmental risk. In addition, problem behaviors potentially reinforce existing family problems, setting in motion further family detachment. Logically, cascading negative consequences are more likely when multiple adversities are present, in which case recovery and resilience are less likely (Smith et al., 2005). Thus, exposure to family violence, along with other family processes, potentially contributes to a cascading series of consequences that lead from short-term reactive responses to entrenched longer term consequences, such as drug and alcohol problems. Our work is also influenced by developmental psychopathology, which suggests that similar experiences can contribute to a wide range of adverse outcomes, which may differ across developmental periods and by gender (Sameroff, 2000; Wolfe et al., 2003).

This interactional conceptualization is consistent with a number of complex etiological theories of adolescent substance use and abuse that invoke family processes (e.g., Brook et al., 1990, 2001; Simons et al., 1988; see Petralis et al., 1995, for a review), yet family violence is rarely, if ever, specified as a core process in any of these major models. Furthermore, although dynamic theoretical models anticipate a link between IPV exposure and subsequent problem substance use, longitudinal research on these hypothesized empirical linkages is scarce. Moreover, IPV, like other forms of family violence, commonly occurs in the context of “socially toxic environments” (Garbarino, 1997, p. 141), including poverty, and other disadvantages such as parental substance abuse (Belsky, 1993; Cox et al., 2003; Emery and Laumann-Billings, 1998; Margolin and Gordis, 2000). Child maltreatment in particular is associated with similar risks and co-occurs with IPV (Appel and Holden, 1998; Hazen et al., 2004). Thus, a full understanding of the role of IPV requires information about other aspects of the family environment.

Literature review: Consequences of exposure to intimate partner violence

Although a range of behavioral problems are noted among children raised in partner-violent homes, the most frequently observed problems are aggression and antisocial behavior (Edleson, 1999; Kolbo et al., 1996; Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Neidig, 1995; Sternberg et al., 1993). The most frequently noted problems among adults retrospectively reporting childhood exposure to IPV include antisocial behavior, as well as partner violence (Doumas et al., 1994; Ehrensaft et al., 2003), although other problems, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol and drug abuse, are also noted (e.g., Dube et al., 2002a, 2003; Henning et al., 1996; Sher et al., 1997). Recent reviews and meta-analyses of exposure to IPV studies also conclude that a wide range of outcomes across multiple domains and across a variety of developmental periods (i.e., childhood, adolescence, and adulthood) may be affected by IPV exposure (Edleson, 1999; Herrenkohl et al., 2008; Kitzmann et al., 2003; Wolfe et al., 2003). No reviews, however, identify substance-use problems as a consequence of exposure to IPV.

A few cross-sectional studies focus on whether substance use during adulthood is a consequence of being raised in a partner-violent home (Caetano et al., 2003; Dube et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2003; Roustit et al., 2009; Trocki and Caetano, 2003). Trocki and Caetano (2003) found that retrospective reports of threatened IPV in a national probability sample were linked to male alcohol dependence but not female alcohol dependence. Heavy episodic drinking was also associated with observing IPV threats for both men and women. Unexpectedly, reports of observed IPV—as opposed to threatened IPV—were not related to outcomes. Caetano et al. (2003) consider adult consequences of retrospectively reported physical abuse and exposure to IPV during childhood and adolescence. The dependent variable was problem alcohol use. They reported a statistically significant interaction between exposure to parental violence (observed or threatened) and child physical abuse for males, but the coefficient was negative, suggesting reduced risk, not increased risk, for alcohol problems. Analyses by race indicated that black males who observed parental violence as a child or adolescent were more likely to report problem alcohol use compared with those who did not observe such violence. Problem alcohol use among women in the sample was unaffected by exposure to parental violence during childhood or adolescence. The three studies by Dube et al. (2002a, 2002b, 2003) analyzed data from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Retrospective data were collected from more than 17,000 respondents regarding witnessing father-directed violence toward the mother. In addition, self-reported maltreatment data were collected along with data on parental substance use. These studies suggest that in multivariate models, more frequent witnessing of IPV is associated with risk for self-reported alcoholism, illicit drug use, intravenous drug use, and depressed affect (Dube et al., 2002b). In addition, Dube et al. (2003) found that retrospective reporting of father violence toward mothers significantly increased the odds of early onset of illicit drug use as well as lifetime illicit drug use. Finally, Dube et al. (2002a) reported a significant relationship between witnessing father-directed IPV and self-reported heavy drinking, alcohol problems, marrying an alcoholic, and self-classification as alcoholic in men as well as women.

A final study using data on a probability sample from France found a significant relationship between a retrospective measure of IPV exposure and adult alcohol dependence in a multivariate model controlling for other family processes as well as demographic variables (Roustit et al., 2009). Furthermore, Roustit et al. (2009, p. 566) reported the risk of “alcohol dependence was higher in male respondents from high-conflict families and/or with a parental history of alcoholism” compared with women.

The work done to date, although informative, demands cautious interpretation because of methodological limitations, including cross-sectional designs with retrospective measures of childhood exposure to IPV collected in adulthood, and variations in sampling as well as in the operationalization of IPV and substance use. As a consequence, the varied conclusions regarding the possible relationship between being raised in a partner-violent home and later substance use in adulthood may be attributed, in part, to differences in samples, methods, and measurement.

In summary, whether exposure to IPV is a risk factor for subsequent substance abuse remains an open question. We could find no truly prospective studies that consider the potential impact of victim characteristics such as gender, characteristics of the abuse such as its severity, and characteristics of the parents, including their substance-use history (Fergusson and Horwood, 1998; Harrier et al., 2001; Maker et al., 1998). Often the unique role of exposure to IPV is unclear because of the measured or unmeasured impact of other forms of family violence and other adversities (Maker et al., 1998). Thus knowledge about longer term adjustment is very incomplete and “will only be answered with the use of longitudinal data” (Wolfe et al., 2003, p. 184). Overall, Herrenkohl et al. (2008) echoed the same sentiment that “the need for additional prospective studies of both abuse and DV (domestic violence) effects is clear, especially those that extend into the adult years” (p. 89).

It is not clear whether one might expect gender differences in the consequences for those raised in partner-violent families. The picture is complicated by the fact that men have higher rates than women of dependence on or abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs from late adolescence into adulthood (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004), and indeed there is evidence that vulnerabilities to substance-use problems may differ by gender (Kaplan and Johnson, 1991; Ritter et al., 2002). However, there is equivocal evidence that male and female responses to family-based violence differ (Fergusson and Horwood, 1998; Miller et al., 1993; Widom, 1998). Among the studies reviewed here, those that estimated models separately for males and females found IPV exposure linked to substance use more consistently for males, but only with outcome measures of alcohol use, not illicit drug use (Dube et al., 2002a; Roustit et al., 2009; Trocki and Caetano, 2003). Supporting this pattern of results, a meta-analysis of studies of childhood impact of IPV showed a somewhat larger effect on men, but differences were not clear-cut, owing to variations in sample characteristics (Wolfe et al., 2003).

Conversely, there is growing evidence in prospective studies on the consequences of child maltreatment that maltreated women are more at risk for some substance-use outcomes than maltreated men (e.g., Widom et al., 1995, 2006, 2007; Widom and White, 1997; Wilson and Widom, 2009). However, this prospective research has focused exclusively on child maltreatment rather than IPV exposure. Therefore, although the retrospective studies on the relationship between IPV exposure during childhood and illicit drug use and alcohol use in adulthood tend to indicate greater risk for males, the prospective studies that consider the relationship between maltreatment in childhood and subsequent illicit drug use and problem alcohol use tend to indicate greater risk for females.

In conclusion, despite theoretical indications that exposure to IPV should have significant life-course consequences, there are substantial gaps in our existing knowledge base as it pertains to subsequent substance use. Overall, we address the general hypothesis that exposure to IPV during adolescence predicts young adult substance-use problems. The following research questions are addressed: (a) Is adolescent exposure to IPV associated with substance-use problems in early adulthood net of other factors including child maltreatment and parental substance use? (b) Does the relationship between exposure to adolescent IPV and early adult substance-use problems differ by gender?

Method

Data for this study were drawn from the RYDS, which was designed to investigate the development of delinquency and other problem behaviors in a representative urban community sample. The study design and sampling procedures are detailed elsewhere and are summarized here (e.g., Smith and Thornberry, 1995). The RYDS is a multiwave panel study in which youths and their primary caretakers, generally the mother, were initially interviewed every 6 months, and then at three annual interviews in young adulthood. Data were collected in two phases. During the first phase, participants were, on average, 14–18 years old; during the second phase they were 21–23 years old. Measures used here were gathered from youth (Generation 2 [G2]) and parental (Generation 1 [G1]) interviews in Phases 1 and 2 or collected from official agencies. All human subject protections were observed and the study has been continually monitored by the institutional review board of the University at Albany.

The initial sample of 1,000 adolescents was selected from the population of seventh and eighth graders in the Rochester, NY, public schools in 1987. Given the original interest in serious delinquency, high-risk youth were oversampled on sex (75% males, 25% females) and on residence in high-crime areas of the city (Krohn and Thornberry, 1999). The original panel included 68% African American, 17% Latino, and 15% White participants. A range of field procedures has been successfully used throughout the study to minimize attrition over time (Thornberry et al., 1993). At the end of the second phase of data collection, in early adulthood, 85% (846) of the initial 1,000 G2 participants were re-interviewed. A comparison of those retained and not retained at the end of Phase 2 revealed no significant differences in demographic characteristics and delinquency between the original panel and those retained (Thornberry et al., 2003).

G1 IPV was assessed during five Phase 1 interviews only if the primary caregiver was involved in a relationship; therefore, those in the sample without married or cohabiting partners were not assessed for partner violence. Thus, for this study we used a subsample of the RYDS that consisted of those youth participants who had a primary caretaker (G1) with a married or cohabiting partner in at least one of the five interviews in which partner violence was assessed. The resulting subsample of 508 G2s—about half the total sample—is 77% male and 23% female, similar to the sex representation in the total sample. The subsample also included 58% African Americans, 18% Latino, and 22% White participants and thus contains proportionally fewer African American participants and more White G2 participants than the total sample. From this point, we refer to this subsample as the sample.

Intimate partner violence

IPV among G1 parents was assessed among those with partners at five 6-month intervals during G2 midadolescence using the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979). The CTS measured perpetration and victimization reported by the primary caretaker, who was the mother or mother figure in the household more than 90% of the time. It contains questions on the occurrence and frequency of 19 tactics employed during partner conflict that range from discussing issues calmly to use of a weapon. The CTS yields violence prevalence and frequency scores for both perpetration and victimization (Straus, 1990). As in other community samples, we found that women reported as much or more violent perpetration compared with violent victimization (e.g., Magdol et al., 1998; Morse, 1995).

We focused on the nine physical violence items from the CTS physical aggression scale, specifically including the following: (a) threw something at partner; (b) pushed, grabbed, or shoved partner; (c) slapped partner; (d) kicked, bit, or hit partner; (e) hit partner with something; (f) beat up partner; (g) choked partner; (h) threatened to use a weapon against partner; and (i) actually used a weapon on partner. Two prevalence measures of CTS violence were used in these analyses. Each measure combined violent perpetration and violent victimization as reported by the G1 caretaker at any wave at which the CTS was administered. Following Straus (1990), total violence uses all nine items described above and severe violence uses only the last six items beginning with item d. In preliminary analysis conducted to isolate a measure that would capture both frequent and severe IPV, we found that the group with severe violence was also the group with the most frequent violence. Therefore, the prevalence measure of severe physical violence captures not only extreme violence but also those reporting frequent IPV. Table 1 shows the prevalence of exposure to total and severe IPV for the full sample and for male and female G2s.

Table 1.

Distribution of intimate partner violence (IPV)

| Variable | G1, any IPV % | G1, any severe IPV % |

| Total sample (n = 508) | 39.2 | 21.3 |

| G2 sex | ||

| Male (n = 390) | 40.0 | 21.8 |

| Female (n = 118) | 36.4 | 19.5 |

| G2 race | ||

| African American (n = 293) | 45.4 | 26.6 |

| Hispanic (n = 102) | 26.5 | 13.7 |

| White (n = 113) | 34.5 | 14.2 |

Notes: G1 = Generation 1; G2 = Generation 2.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures employed in this study derive from data reported by G2 participants in their early 20s. Table 2 shows the prevalence of several self-reported indicators of problem alcohol or drug use, including illicit drug use, drug-use problems, heavy drinking, and alcohol-use problems. Any illicit drug use is a positive report over the three interviews of use for any of 10 illegal drugs, including marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and amphetamines. An index of drug-use problems similar to the list of diagnostic symptoms of drug abuse was used for those who reported drug use. Items included having experienced problems at work, with the police, with close family, with health; trying to cut down but not being able to; getting into fights; needing larger amounts to get high; and not remembering events subsequent to use. A participant who responded affirmatively to any of the drug-use problems over the three interviews was assigned a value of 1 and all others were assigned a value of 0. A participant who reported consuming more than five drinks at one sitting in the past 2 weeks during any of the three annual interviews was classified as having engaged in heavy drinking. Alcohol-use problems included a report of one or more problems on the alcohol problem scale, which is similar to the drug problem scale described above. The substantially greater prevalence of indicators for drug and alcohol-use problems for men compared with women parallels well-established findings in national surveys (Compton et al., 2007; Hasin et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Distribution of outcomes, control variables, and related predictors

| Variable | Full sample % or M | na |

| Early adult outcomes | ||

| Any drug use | 51.2% | 477 |

| (Male: 56.8%; Female: 33.9%) | ||

| Any drug-use problems | 16.9% | 467 |

| (Male: 19.7%; Female: 8.0%) | ||

| Any heavy drinking | 36.2% | 450 |

| (Male: 42.2%; Female: 17.4%) | ||

| Any alcohol-use problems | 28.5% | 466 |

| (Male: 32.5%; Female: 16.1%) | ||

| Control variables | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 76.8% | 508 |

| Female | 23.2% | 508 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 57.7% | 508 |

| Hispanic | 20.1% | 508 |

| White | 22.2% | 508 |

| G2 adolescence | ||

| Caregiver transitions | 1.25 (mean) | 473 |

| Family poverty, no. of waves | 1.47 (mean) | 484 |

| Adolescent drug use or alcohol problems | 35.6% | 491 |

| G2 early adult | ||

| G2 married | 13.3% | 467 |

| G2 high school graduate | 64.3% | 470 |

| Other predictors | ||

| Parental substance use | 23.4% | 508 |

| Adolescent maltreatment | 6.9% | 508 |

Notes: G2 = Generation 2.

n available for each variable.

Control variables

Table 2 also summarizes eight control variables that were included in multivariate analyses because they are related to both violence in the family and/or substance use and their effects have typically been controlled in previous studies (e.g., Smith and Thornberry, 1995; Widom, 1991; Zingraff et al., 1993). Race/ethnicity included three categories: African American, Hispanic, and White. Family poverty measured the number of waves in poverty in the first four waves when G2 respondents were approximately 14–16 years old. Any one of three indicators was used to measure poverty: income below the federal poverty line, unemployment, or receipt of public assistance. Family transitions counted transitions in parental figures over the adolescent interview waves. We also controlled for two factors that have been found to predict substance-use problems in early adulthood: G2 marital status and G2 education, measured respectively by whether the respondent had married or completed high school by Wave 12. Adolescent substance use combined any report of drug use or alcohol-use problems during late adolescence (ages 16–18).

The multivariate models also included measures of G2 maltreatment during adolescence and G1 substance use because both may be important confounding factors. G2 maltreatment data come from Child Protective Service records in Monroe County, the adolescents' county of residence at the start of the RYDS. Details on each maltreatment incident, from birth to age 18, were coded according to a classification system developed by Cicchetti and Barnett (1991), which has shown good reliability and validity both with other data (Barnett et al., 1993) and within the RYDS (Smith and Thornberry, 1995). We used a measure of any adolescent exposure to maltreatment to parallel the IPV measures that were also collected during G2 adolescence. Parental substance use came from a report by G1 primary caretakers, mainly mothers, during G2's adolescence. G1 substance use was coded as present when a caretaker reported the use of marijuana, use of any other illicit drug, or frequently drinking more than three drinks during one sitting at any wave (Waves 2–8). Because more than 90% of G1 respondents were G2's mother, this measure referred predominantly to maternal substance use (Table 2).

Results

We first addressed the general hypothesis that G1 IPV during G2 adolescence predicts G2 early adult substance-use problems. Table 3 displays the results of a series of logistic regression models exploring the simple bivariate relationships between exposure to IPV and the four alcohol and other drug (AOD) outcomes—illicit drug use, any drug-use problem, heavy drinking, and any alcohol problem—for the full sample, and for males and females separately. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals are presented. The top panel shows no significant relationship between exposure to any IPV and any of the four AOD outcomes for the full sample and for males and females separately. However, it should be noted that there were differences in the magnitude of ORs for men and women. Women exposed to any IPV in adolescence had higher odds of all AOD indicators compared with women without IPV exposure, whereas this was not the case for men.

Table 3.

Bivariate association between intimate partner violence (IPV) exposure and outcomes related to alcohol and other drugs (unadjusted odds ratios)

| Early adult outcomes | Full sample (n = 508) Odds ratio [CI] Odds ratio [CI] | Males (n = 390) Odds ratio [CI] | Females (n = 118) Odds ratio [CI] |

| Any IPV exposure | |||

| Any drug use | 0.97 [0.67, 1.42] | 0.81 [0.53, 1.25] | 1.52 [0.68, 3.44] |

| Any drug-use problem | 1.07 [0.65, 1.74] | 0.99 [0.58, 1.68] | 1.43 [0.36, 5.65] |

| Heavy drinking | 0.79 [0.53, 1.17] | 0.67 [0.43, 1.04] | 1.32 [0.48, 3.61] |

| Any alcohol-use problem | 0.96 [0.64, 1.45] | 0.76 [0.48, 1.20] | 2.54 [0.91, 7.08] |

| Severe IPV exposure | |||

| Any drug use | 1.22 [0.78, 1.91] | 1.05 [0.63, 1.75] | 1.78 [0.66, 4.79] |

| Any drug-use problem | 0.75 [0.40, 1.39] | 0.66 [0.34, 1.30] | 1.26 [0.24, 6.57] |

| Heavy drinking | 0.95 [0.60, 1.52] | 0.80 [0.48, 1.33] | 1.79 [0.56, 5.71] |

| Any alcohol-use problem | 1.29 [0.80, 2.07] | 1.00 [0.59, 1.70] | 3.64* [1.21, 10.98] |

p < .05.

For exposure to severe IPV, displayed in the bottom panel of Table 3, we found a similar pattern. For the full sample and for males, exposure to severe IPV did not predict any AOD outcomes. However, again, there was a difference for men and women. Women exposed to severe IPV trended toward higher odds of problem substance use than women not so exposed, and in the case of any alcohol problem, there was a statistically significant result for women. Women exposed to severe IPV had more than three times the odds of reporting at least one alcohol problem in early adulthood than did women not so exposed. Our next step examined whether the relationship between adolescent exposure to severe IPV and alcohol-use problems for young women continued to be evident in a multivariate model.

The multivariate analyses also used logistic regression models to predict the four early adult outcomes: illegal drug use, any drug-use problems, heavy drinking, and any alcohol-use problems. Each cell in Table 4 represents a separate logistic regression model that includes the focal independent variable G1 severe IPV, and as covariates race/ethnicity, family poverty, caregiver transitions, G1 substance use, G2 adolescent maltreatment, G2 substance use during late adolescence, G2 educational attainment, and G2 marital status. For the full-sample models, we also controlled for the sex of G2. The coefficients presented in Table 4 are adjusted ORs with confidence intervals.

Table 4.

Multivariate relationship between exposure to severe intimate partner violence (IPV) and outcomes regarding alcohol and other drugs (adjusted odds ratios)

| Early adult outcomes | Full sample (n = 508) Odds ratio [CI] | Males (n = 390) Odds ratio [CI] | Females (n = 118) Odds ratio [CI] |

| Any drug use | 1.06 [0.61, 1.87] | 0.95 [0.50, 1.81] | 2.27 [0.62, 8.31] |

| Any drug-use problem | 0.50 [0.24, 1.03] | 0.47 [0.21, 1.02] | 0.80 [0.07, 9.18] |

| Heavy drinking | 0.71 [0.40, 1.26] | 0.63 [0.33, 1.19] | 1.28 [0.30, 5.44] |

| Any alcohol-use problem | 1.20 [0.67, 2.14] | 0.90 [0.47, 1.72] | 5.63* [1.25, 25.36] |

Notes: Logistic regression models control for race, family poverty, caregiver transitions, maternal substance use, adolescent maltreatment, adolescent drug use or alcohol problems, early-adult marital status, and early-adult educational attainment. Full sample models also control for sex.

p < .05.

Consistent with the bivariate results, there were no significant differences in the predicted odds of drug use, drug-use problems, heavy drinking, or alcohol-use problems for either the full sample or for young G2 men exposed to severe IPV during adolescence compared with those not exposed to severe IPV, controlling for the other factors. However, young G2 women exposed earlier to severe IPV had significantly higher odds of reporting any alcohol-use problems compared with young women not exposed to severe IPV, holding covariates constant (OR = 5.63, p < .05). Young women exposed to severe IPV also had higher odds of drug use and heavy drinking than young women not exposed, holding covariates constant, but neither coefficient was statistically significant. There was also no difference in the predicted odds of drug-use problems for young women exposed to severe IPV compared with those not so exposed, controlling for other factors. We also estimated multivariate models using total IPV as our focal predictor and, consistent with the bivariate results, we found no significant effects (results not shown but available on request).

The effect of covariates varied across the logistic regression models, but some patterns emerged (results not shown but available on request). As would be expected, adolescent substance-use problems significantly predicted adult substance-use problems for both sexes for every outcome, holding exposure to severe IPV and other covariates constant. Sex was also a significant predictor in the full-sample models, with males having two to three times the odds of all four AOD outcomes compared with females. There were no differences in drug-use outcomes across racial/ethnic groups, but African Americans, particularly males, had significantly lower odds of heavy drinking and any alcohol problem than Whites, controlling for other covariates. Hispanics also had lower odds of alcohol-use outcomes than Whites, but this difference was only marginally significant. High school graduates had significantly lower odds of drug use, any drug problem, and any alcohol problem than those who had not completed high school, but there was no difference between these groups in heavy drinking, holding other factors constant. Married respondents had lower odds of drug use and any drug problem, but there were no significant differences in alcohol outcomes between married and single participants, controlling for severe IPV exposure and other covariates. Maternal substance use predicted heavy drinking, and, for the females only, was a marginal predictor of drug-use problems, controlling for other factors. Although adolescent maltreatment predicted higher odds for all AOD outcomes, the differences were not statistically significant when holding other covariates constant. Family poverty significantly increased the odds of any alcohol-related problem and marginally increased the odds of heavy drinking for female, but not male, participants when controlling for exposure to severe IPV and other covariates. Finally, family stability was not a significant predictor of any AOD outcome for either sex, when holding severe IPV exposure and other covariates constant. These results are generally consistent with the literature but also indicate possible differences between males and females that warrant further exploration.

The somewhat different results for young women exposed to severe IPV as compared with young men prompted us to examine formally whether there is an interaction effect between sex and exposure to severe IPV particularly in relation to early adult alcohol problems. Logistic regressions were conducted for all four outcomes using the full sample and including, in addition to the covariates described above, a product term of Severe IPV × Sex to test for an interaction effect. We did not find a significant moderating effect by sex on the relationships between severe IPV and drug use, drug-use problems, or heavy drinking. However, we did find that sex significantly moderates the relationship between G1 severe IPV and G2 early adult alcohol-use problems.

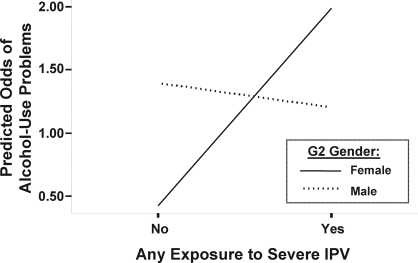

As shown in Figure 1, the predicted odds of alcohol-use problems for young men exposed to severe IPV in adolescence were almost the same as the predicted odds for young men not exposed to severe IPV, controlling for other factors, resulting in a flat slope and a non-significant simple main effect. Young women exposed to severe IPV, however, had significantly higher predicted odds of alcohol-use problems than young women not exposed to severe IPV, holding covariates constant (OR = 4.68, p < .05). Thus, the slope of the relationship between exposure to severe IPV and alcohol-use problems shows a significant interaction effect by sex: It is flat for young men but is quite steep for young women. We also tested for interaction effects using exposure to any IPV x Sex and found a significant interaction effect between sex and exposure to any IPV in predicting any alcohol problems that showed similar slopes for males and females as described for exposure to severe IPV (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Sex as a moderator of the association between any exposure to severe intimate partner violence (IPV) and any alcohol-use problem. The predicted odds are calculated for the group who had experienced theoretically predictive factors, such as maternal substance use, and were the most average in relation to the other covariates. This group consists of African Americans with an average level of family poverty and caregiver transitions who experienced adolescent maltreatment and maternal substance use, used illegal drugs in adolescence, and graduated from high school but had not been married by age 23. It should be noted that, although the level of control variables affects the predicted odds, it does not affect the odds ratios involved in the simple main effects or interaction effects.

In summary, we found that exposure to IPV—either total or severe—in adolescence does not predict drug- or alcohol-use problems in early adulthood for males, who comprised the majority of our sample. However, we did find one significant difference between males and females in the relationship between exposure to IPV and AOD outcomes. Our findings indicate that, for this urban sample, the association between exposure to severe IPV in adolescence and alcohol-use problems in early adulthood does indeed differ by sex.

Discussion

Our major objective was to investigate whether adolescent exposure to parental IPV predicted increased substance-use problems in young adults. We considered four different substance-use outcomes in early adulthood and found that for our full sample, three quarters of whom are male, neither exposure to any IPV nor exposure to severe IPV during adolescence increased the risk for substance-use problems. Our second objective was to investigate whether IPV predicts substance-use problems differentially for men and women. In addressing this question, we did find one significant sex difference in the relationship between IPV exposure and substance-use outcomes. For young men, exposure to any IPV or severe IPV in adolescence did not increase the risk for illegal drug use, any drug-use problem, heavy drinking, or any alcohol problem in early adulthood. For young women, however, our results suggest that exposure to severe IPV and, more marginally, exposure to any IPV in adolescence increases the risk of alcohol problems in early adulthood.

Our investigation was hampered by the limited number of G2 women (n = 118) in the sample, which resulted from restriction to G1s with partners. Combined with lower rates of substance-use problems among the female respondents, this resulted in small cell sizes, model instability, and low power to detect significant results in the analyses performed separately on the female subsample. Therefore, we cannot report clear-cut sex differences in the impact of IPV on, for example, illegal drug use, which are suggested by the magnitudes of the ORs in both our bivariate and multivariate models. However, the significant moderating effect by sex that we found for the relationship between exposure to IPV and any alcohol problems in early adulthood, combined with the different patterns in the magnitude of ORs for male and female participants suggests a real difference between young men and women in the impact of adolescent exposure to IPV, particularly severe IPV, on early adult substance-use problems. Although this sex difference has been presaged in previous research on the impact of child maltreatment (e.g., Widom and White, 1997), this is the first test of a sex-specific effect of exposure to IPV on later substance use in a fully longitudinal design controlling for many relevant potentially confounding variables.

The most closely aligned literature that relies on longitudinal, prospective data is the research conducted by Widom and her colleagues. In sex-specific models, she has reported that child abuse and neglect experiences during childhood are indirectly, but significantly, related to alcohol use and excessive drinking among females, but not males, in middle adulthood (Widom et al., 2007) and that a similar pattern emerges for illicit drug use in middle adulthood as well (Widom et al., 2007; Wilson and Widom, 2009). Although we did not find a definitive link between IPV exposure during adolescence and illicit drug use in early adulthood among the RYDS females, we did find a link between IPV exposure during adolescence and alcohol problems in early adulthood.

This finding is surprisingly in contrast with retrospective studies that have found a relationship between growing up in a partner-violent home and substance use among males. These varying sex results might be the result of the rather substantial differences in the ages of the retrospective samples compared with the RYDS sample, the measurement strategies used to operationalize both exposure to IPV and substance use, or the methodology employed—retrospective versus prospective designs. In the series of recent Widom studies on the relationship between child maltreatment and drug or alcohol use in adulthood, it is important to note that there was no relationship between child maltreatment and drug use for either males or females in early adulthood (Widom et al., 1999), but there was a relationship between child maltreatment and alcohol use in early adulthood among women (Widom et al., 1995)—to some degree, these results are parallel to the results presented here, with IPV as a predictor instead of child maltreatment. Perhaps for the influence of IPV exposure in the RYDS sample as well, the effects on drug abuse will show up more clearly later in the life course, as Wilson and Widom (2009) have shown for maltreatment.

Other variables in the analysis clearly play a role in substance-use outcomes, and some appear to play a role in the relationship between adolescent exposure to IPV and certain substance-use outcomes, either enhancing or suppressing the strength of the association. For example, for the female subsample, adding the covariates to the regression models increased the magnitude of the OR for the association between exposure to severe IPV and any drug use, as well as exposure to severe IPV and any alcohol problem, but it decreased the magnitude of the OR for the association between exposure to severe IPV and any drug-use problem and exposure to severe IPV and heavy drinking. In addition, we found indications that certain covariates, including maternal substance use and family poverty, have differential effects on substance-use outcomes for young women compared with young men. Although a more detailed exploration of these relationships is beyond the scope of this article, they underline the importance of contextual factors in the influence of family violence on adult outcomes, including substance-use problems, and in the different long-term effects that family violence may have on women and men.

Some additional limitations of the current study should be noted. First, we are limited to considering only exposure to IPV among adolescents because of the prospective design of the study. In previous analyses with the RYDS, we considered the consequences of officially substantiated maltreatment occurring at different ages, and found that maltreatment that occurred in adolescence was particularly developmentally detrimental (Ireland et al., 2002; Thornberry et al., 2001). Determining whether the consequences of exposure to IPV are affected by age of exposure to IPV will require prospective data from birth to age of majority, which to date are unavailable in any studies that we are aware of. As a result, although there is a literature on the consequences of exposure to family violence among infants, toddlers, and school-age children (see Osofsky, 1999, for a review), we were unable to consider whether the developmental consequences for children exposed to IPV are more disruptive than, less disruptive than, or similar to consequences for adolescents exposed to IPV.

A second limitation relates to the measure of partner violence used in this study: Straus's CTS. Although this measure is the most widespread measure of IPV in current use, it has been criticized for lacking information about the context and heterogeneity of partner violence (DeKeseredy et al., 1997; Dobash et al., 1992). The most recent version was not used in this investigation because it was developed after the study started. We have only the primary (generally maternal) caretaker's version of violence perpetrated and experienced and generally lack information from fathers on their behavior, including their substance use, which may be involved in the intertwined cycles of addiction and violence.

In addition, we could have used other CTS measurement strategies, including a combined measure of physical and psychological violence, and a stand-alone measure of psychological violence. However, in the empirical literature we reviewed, the operationalization of exposure to IPV was almost exclusively a single question asking adults if they recalled violent interactions between their caregivers during childhood and adolescence. We expanded on this measurement scheme by using prospective data and multiple items from the CTS. We also considered any physical violence as well as any severe physical violence. We opted to parallel and improve on the measurement strategy used to assess exposure to physical violence in the family. Furthermore, in our urban sample we found that levels of psychological violence had limited variability because of the very high prevalence rate. However, future studies should consider not only physical violence but also psychological violence.

Third, we did not include in these analyses participants who did not report a cohabitating or married partner during the 2.5-year window during which CTS data were collected. Although focusing only on partner samples is common in the literature (e.g., Caetano et al., 2003; Capaldi et al., 2003), missing data on those in a relationship that has not progressed to marriage or cohabitation is a limitation of the study. Ideally, we would have data on those (a) not in a relationship, (b) in a cohabitating or married relationship, and (c) in a relationship but who are not married or cohabitating. It is conceivable that this third group might be at greatest risk for IPV and, as a result, findings presented here are probably conservative estimates of the relationship between IPV exposure in adolescence and drug and alcohol-use problems in early adulthood.

Finally, because this is a relatively high-risk sample, rates of female alcohol and drug use are high; therefore, differences between the exposed and non-exposed groups were muted, and risk in general was high, possibly limiting our ability to detect a specific impact from IPV.

Despite these limitations, this study incorporates several powerful design and measurement features, including prospective data over several assessment periods, longitudinal assessment of outcomes, and stringent controls for confounding factors. The current study addresses several limitations of past studies. First, our measure of exposure to IPV is based on parental reports during the study participants' mid-adolescence. As such, our measures of exposure to IPV do not rely on our study participants' retrospective recall in adulthood of events occurring during adolescence. Second, the data are from a large, diverse community-based sample. Third, multiple measures of alcohol- and drug-use outcomes are available. Fourth, we are able to statistically control for potentially spurious effects, including parental substance use and maltreatment during adolescence. Finally, we are able to establish proper temporal order between the measures of exposure to IPV collected during mid-adolescence and the measures of substance use collected during early adulthood.

With these strengths, the study adds new knowledge to the family-violence and substance-abuse fields. Overall, but particularly for the young men in this high-risk community sample, we found less association between adolescent exposure to IPV and early adult substance-use problems than we expected. For young women, however, we found a positive relationship between exposure to IPV in adolescence and alcohol problems in early adulthood. This is consistent with evidence of a stronger relationship between child maltreatment and adult alcohol problems for women, and indicates the need for efforts targeted at preventing adverse outcomes resulting from family violence for young women.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants 5 RO-1 DA20344, 5 RO-1 DA05512, and R36 DA024778; Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice grant 86-JN-CX-0007; and National Science Foundation (NSF) grant SES-8912274. Work on this project was also aided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant P30 HD32041 and NSF grant SBR-9512290 awarded to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany.

References

- Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:578–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bardone AM, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Dickson N. Adult mental health and social outcomes of adolescent girls with depression and conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Balka EB, Cohen P. Parent drug use, parent personality and parenting. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2001;156:137–151. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1995.9914812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushway SD, Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. Desistance as developmental process: A comparison of static and dynamic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2003;19:129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Nelson S. Association between child physical abuse, exposure to parental violence, and alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:240–257. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B. Children exposed to intimate partner violence: Research findings and implications for intervention. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2000;1:321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Barnett D. Toward the development of a scientific nosology of child maltreatment. In: Gove W, Cicchetti D, editors. Thinking clearly about psychology: Essays in honor of Paul E. Meehl: Vol. 2. Personality and psychopathology. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1991. pp. 346–377. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas Y, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CE, Kotch JB, Everson MD. A longitudinal study of modifying influences in the relationship between IPV and child maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy W, Daunders DG, Schwartz M, Alvi S. The meanings and motives for women's use of violence in Canadian college dating relationships: Results from a national survey. Sociological Spectrum. 1997;17:199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash RP, Dobash RE, Wilson M, Daly M. The myth of sexual symmetry in marital violence. Social Problems. 1992;39:71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas D, Margolin G, John RS. The intergenerational transmission of aggression across three generations. Journal of Family Violence. 1994;9:157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors. 2002a;27:713–725. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Williamson DF. Exposure to abuse, neglect and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: Implications for health and social services. Violence and Victims. 2002b;17:3–17. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect and household dysfunction and risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edleson JL. Children's witnessing of adult IPV. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:839–870. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Laumann-Billings L. An overview of the nature, causes, and consequences of abusive family relationships: Toward differentiating maltreatment and violence. American Psychologist. 1998;53:121–135. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst AA, Weiss SJ, Enright-Smith S. Child witnesses and victims in homes with adult intimate partner violence. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13:696–699. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, Fusco RA. Children's direct exposure to types of domestic violence crime: A population-based investigation. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:543–552. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:339–357. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. Growing up in a socially toxic environment. In: Cicchetti C, Toth SL, editors. Developmental perspective on trauma: Theory, research and intervention. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Bermann SA, Edleson JL. IPV in the lives of children: The future of research, intervention, and social policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harrier LK, Lambert PL, Ramos V. Indicators of adolescent drug users in a clinical population. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;10:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CC. The co-occurrence of child maltreatment and IPV: Examining both neglect and child physical abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:349–358. doi: 10.1177/107755902237264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:829–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen AL, Connelly CD, Kelleher K, Lansverk J, Barth R. Intimate partner violence among female caregivers of children reported for child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:301–319. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning K, Leitenberg H, Coffey P, Turner T, Bennett RT. Long-term psychological and social impact of witnessing physical conflict between parents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2008;9:84–99. doi: 10.1177/1524838008314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW. Children exposed to IPV and child abuse: Terminology and taxonomy. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:151–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1024906315255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland T, Smith CA, Thornberry TP. Developmental issues in the impact of child maltreatment on later delinquency and drug use. Criminology. 2002;40:359–399. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe PG, Wolfe D, Wilson S. Children of battered women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975– 2006: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIH Publication No. 07-6206) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Norwood WD, Ezell E. Issues and controversies in documenting the prevalence of children's exposure to IPV. In: Graham-Bermann SA, Edleson JL, editors. IPV in the lives of children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Norwood WD, Ware HS, Spiller LC, Swank PR. Knives, guns, and interparent violence: Relations with child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB, Johnson RJ. Negative social sanctions and juvenile delinquency: Effects of labeling in a model of deviant behavior. Social Science Quarterly. 1991;72:98–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbo JR, Blakely EH, Engleman D. Children who witness IPV: A review of empirical literature. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Thornberry TP. Retention of minority populations in panel studies of drug use. Drugs and Society. 1999;14:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Neidig P. Violence backgrounds of economically disadvantaged youth: Risk factors for perpetrating violence? Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, Von EA. New directions for research on intimate partner violence and children. European Psychologist. 2007;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Figueredo AJ, Koss MP. The effects of systemic family violence on children's mental health. Child Development. 1995;66:1239–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maker AH, Kemmelmeier M, Peterson C. Long-term psychological consequences in women of witnessing parental physical conflict and experiencing abuse in childhood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:574–589. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Downs WR, Testa M. Interrelationships between victimization experiences and women's alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:109–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse BJ. Beyond the Conflict Tactics Scale: Assessing gender differences in partner violence. Violence and Victims. 1995;10:251–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky JD. The impact of violence on children. The Future of Children. 1999;9:33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky JD. Prevalence of children's exposure to IPV and child maltreatment: Implications for prevention and intervention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:161–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1024958332093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno J. Safe from the start: The national summit on children exposed to violence. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter J, Stewart M, Bernet C, Coe M, Brown SA. Effects of childhood exposure to familial alcoholism and family violence on adolescent substance use, conduct problems, and self-esteem. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:113–122. doi: 10.1023/A:1014803907234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BBR. Longer term effects of children's exposure to IPV. In: Graham-Bermann SA, Edleson JL, editors. IPV in the lives of children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BBR, Rosenberg MS. The multiple victimization of children: Incidence and conceptual issues. In: Rossman BBR, Rosenberg MS, editors. Multiple victimization of children: Conceptual, developmental, research and treatment issues. New York: Haworth Press; 1999. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Roustit C, Renahy E, Guernec G, Lesieur S, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Exposure to interparental violence and psychosocial maladjustment in the adult life course: Advocacy for early prevention. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63:563–568. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BE. Understanding children exposed to violence: Toward an integration of overlapping fields. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:356–376. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer RB, Wickrama KAS, Keith PM. Stress in marital interaction and change in depression: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19:578–594. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gershuny BS, Peterson L, Gail R. The role of childhood stressors in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:414–427. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Conger RD, Whitbeck LB. A multistage social learning model of the influences of family and peers upon adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Drug Issues. 1988;18:293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Ireland TO, Thornberry TP. Multiple types of family violence exposure and early adult outcomes; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Life History Research in Psychopathology; Portland, OR. (2005, September). [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33:451–481. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg KJ, Lamb ME, Greenbaum C, Cicchetti D, Dawud S, Cortes RM, Lorey F. Effects of IPV on children's behavior problems and depression. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scale. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Appendix B: New scoring methods for violence and new norms for the conflict tactics scales. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Children as witnesses to marital violence: A risk factor for lifelong problems among a nationally representative sample of American men and women. Report of the Twenty-Third Ross Round-table. Columbus, OH: Ross Laboratories; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Office of Applied Studies) Gender differences in substance dependence and abuse. The NSDUH Report (National Survey on Drug Use and Health) Rockville, MD: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Bjerregaard B, Miles W. The consequences of respondent attrition in panel studies: A simulation based on the Rochester Youth Development Study. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1993;9:127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA. Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022574208366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The development of delinquency: An interactional perspective. In: White SO, editor. Handbook of youth and justice. New York: Plenum Press; 2001. pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Trocki KF, Caetano R. Exposure to family violence and temperament factors as predictors of adult psychopathology and substance use outcomes. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2003;14:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Wall AM. Introduction: The overlap between relationship violence and substance abuse. In: Wekerle C, Wall AM, editors. The violence and addiction equation: Theoretical and clinical issues in substance abuse and relationship violence. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The role of placement experiences in mediating the criminal consequences of early childhood victimization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:195–209. doi: 10.1037/h0079252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Childhood victimization: Early adversity and subsequent psychopathology. In: Dohrenwend BP, editor. Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Ireland TO, Glynn PJ. Alcohol abuse in abused and neglected children followed-up. Are they at increased risk? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:207–217. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Marmorstein NR, White HR. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB. Childhood victimization and drug abuse: A comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:867–880. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, White HR. Problem behaviors in abused and neglected children grown up: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance abuse, crime and violence. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1997;7:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, White HR, Czaja SJ, Marmorstein NR. Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on alcohol use and excessive drinking in middle adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:317–326. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. A prospective examination of the path from child abuse and neglect to illicit drug use in middle adulthood: The potential mediating role of four risk factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:340–354. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D. Children exposed to partner violence. In: Jasinski JL, Williams LM, editors. Partner violence: A comprehensive review of 20 years of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 73–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children's exposure to IPV: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:171–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024910416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff MT, Leiter J, Myers KA, Johnson MC. Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology. 1993;31:173–202. [Google Scholar]